CHAPTER 32

Outside Transfers: Retire

Many private company owner-managers transfer their business to an outsider prior to retirement. Often the owners want a lifestyle change. Even though the ultimate transfer occurs to an outsider, some of the transfer methods described in earlier chapters can be incorporated into the sale. For example, it is possible to use charitable trusts, private annuities, or grantor-retained annuity trusts as vehicles for the transfer to an outside buyer. This chapter discusses the proper timing for an outside transfer, the players that might assist with the transfer, the main approaches and marketing processes used to access the market, and the steps required to get to a satisfactory closing of the transaction.

Private business owners have a tendency to control most aspects of their companies. Controlling the transfer process is the last big challenge for an owner who probably has only one chance at the brass ring. Although there is an entire transfer industry at an owner's disposal, this process is too important to be blindly outsourced. The information presented in this chapter enables an owner to play an active part in the transfer.

In business, timing is often everything. This is especially true when a private business owner attempts to create an exit. Often it is difficult to transfer a private business. Most owners are surprised to find that it is easier to get into business than it is to get out. A multitude of variables must be aligned to enable a successful transfer. Even timing has multiple variables. Proper timing of any business transfer is paramount to achieving a maximizing solution. Transfer timing is comprised of personal, business, and market timing. Transfer timing can be likened to winning on a slot machine. Unless all three timing slots are aligned, there is no possibility of a big payout. Exhibit 32.1 depicts this gaming/timing metaphor.

The first slot represents the owner's personal timing. The owner must be physically, mentally, financially, and socially prepared to execute a transfer. The second slot is business timing. Good business timing exists when the company is well positioned to attract positive attention by virtue of its internal operations, management techniques, and financial performance. Market timing refers to the activity level for transferring a business interest in the marketplace. A “good” market is characterized by aggressive buyer activity both in terms of interest levels and acquisition multiples. The most successful transfer, from an owner's perspective, occurs when these three slots are in alignment.

Generally a less-than-satisfactory result occurs if any of the timing slots are out of calibration. For instance, owners who are not in a strong personal position to transfer the business may find it necessary to sell at less-than-optimum price or terms. Of course, if the business is not ready to transfer, it is unlikely that outside offers will be attractive to the owner. If the market does not support the sales process, either the transfer will not occur or it will occur at less-than-optimal price and terms.

EXHIBIT 32.1 Transfer Timing

EXHIBIT 32.2 Preparation Steps for a Business Transfer

| Personal | Business | Market |

| Reduce dependence of owner | Improve the financial records | Ride the wave |

| The owner should not be central to the operations of the business. The sales team should handle key customer accounts. The management team should be running the business. The owner spends the most time on strategic issues. | Audited financial statements may be expensive, but they more than pay for themselves in the transfer process. Audited statements reduce risk from a buyer's perspective. Companies should also clean up all legal issues, such as lawsuits and environmental issues, prior to marketing a business. | Peak selling cycles in the overall private capital markets tend to happen every 5 to 7 years. Normally the crest of this merger wave occurs in the last 18 to 24 months of the cycle. Various investment banking organizations track these cycles. |

| Continue to take out money | More and better systems | Consolidators may be watching |

| The owner can continue to take money out of the company, as these items will be recast. The key here is good record keeping so a buyer can trace all owner compensation. | Financial and management systems should be upgraded. Companies should be able to track product line profitability, capacity requirements, sales forecasts by stock-keeping unit, etc. The more control a company has over its business, the more a buyer will respect the selling process. | Many industries continue to consolidate, in some cases, on a global basis. Typically there are a handful of consolidating companies that intend to grow through acquisition. Often private equity groups control these acquirers. Owners should monitor the activities of consolidators, usually through trade associations and the media. |

| Get estate in order | Clean up the place | Keep an eye open |

| Estate planning can require years to effect. The best plans are proactive, not reactive. Owners wishing to implement sophisticated techniques should seek professional help. | Clean and organized facilities make a positive difference. In some cases, it makes sense for the owner to have phase I or II environmental audits performed before the selling process begins. | The market may present itself at a moment's notice. Special one-time opportunities may knock on the owner's door. |

PREPARATION FOR A TRANSFER

There are a host of activities an owner can undertake to prepare for a transfer. Exhibit 32.2 shows the planning steps that correlate to the timing slots just described.

Successful owners incorporate these action steps, in preparation for a business transfer, into their business plans. If retirement follows the closing of the deal, a capable management team must be in place. Obviously, building a quality management team takes years to accomplish. Owners who cannot remove themselves from daily operations tend to receive less for their company and face the privilege of signing a multiyear employment agreement with the new owner.

TRANSFER PLAYERS

There are thousands of business brokers, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) intermediaries, and investment bankers in the United States ready to assist owners in transferring their business. These players inhabit the private capital markets.

- Business broker. The International Business Brokers Association defines a business broker as one “who works with either buyers or sellers of businesses to help them realize their goals.”1 Business brokers provide a range of services including seller and buyer representation, arranging financing for a deal, and generating market valuations.

- M&A intermediary. M&A intermediaries focus on providing merger, acquisition, and divestiture services to middle-market companies. Hundreds of firms specialize in this area. For discussion purposes, all other practitioners are grouped in this category. For instance, some lawyers, CPAs, and financial consultants also act as M&A intermediaries.

- Investment banker. Investment bankers specialize in raising the capital that businesses require for long-term growth, and they advise firms on strategic matters involving mergers, acquisitions, and other transactions. Public investment bankers assist public companies in accessing the public capital markets. Private investment bankers help private companies access the private capital markets. This chapter describes only the latter.

Exhibit 32.3 shows a comparison between the various transfer players. Transaction size is the most obvious difference between the players. Business brokers typically complete transactions of less than $2 million. Both M&A intermediaries and private investment bankers work on deals up to $100 million or more. Public investment bankers normally work on larger transactions but may be involved in divestitures or other smaller deals.

EXHIBIT 32.3 Comparison of Transfer Players

The ability to raise capital also distinguishes the players. Business brokers and intermediaries may help arrange loans to close a deal, but typically they are not active with private placements or syndications or in raising equity. Private investment bankers normally can raise the entire capital structure offered in the private capital markets. Public investment bankers access the entirety of the private and public capital markets.

The size and sophistication of the goals influences whom to hire. Several questions help filter the players.

- Is the firm familiar with all appropriate value worlds?

- Is the firm able to draw from all capital access points in assembling financing?

- Is the firm familiar with the rich variety of alternatives in the private transfer spectrum?

Answers to these questions and many others will help an owner determine the appropriate player to engage.

MARKETING PROCESSES

The circumstances and needs of the owner lead to the selection of an appropriate marketing process for the business. The three broad marketing processes are negotiated, private auction, and public auction. A negotiated selling process is warranted when only one prospect is identified and the entire process is focused on that prospect. A private auction process is used when a handful of prospects are identified. A public auction process announces the opportunity to the market. Further description of these processes is shown in Exhibit 32.4.

EXHIBIT 32.4 Marketing Processes

A seller should match her needs with one of these marketing processes. Hybrid forms can be used. For instance, a negotiated transfer process may involve several buyers simultaneously, each at different points in the process. Business brokers typically use this process. There may be a handful of buyers interested in purchasing the company, some of whom are making offers while a few may be meeting the owner for the first time. A private auction, however, may be used for as few as one or two prospective buyers but ideally involves more. In this case, the process is orchestrated to convince the buyers that an auction is under way.

Private and public auctions each have one- and two-step variations. A one-step auction is like herding cattle with prospective buyers playing the part of stampeding bovines. The intermediary attempts to maintain control and keep the procession as orderly as possible. With a fair amount of skill and some luck, a buyer might be corralled into paying a fair price. A two-step auction is more formal than the one-step auction. The two steps are staged with specified deadlines.

The negotiated and private auction marketing processes are described at length in the next section. The public auction process is quite similar to the private auction, except the former employs a mass marketing approach. Since this book is targeted at private companies, the public auction is not detailed here.

NEGOTIATED TRANSFERS

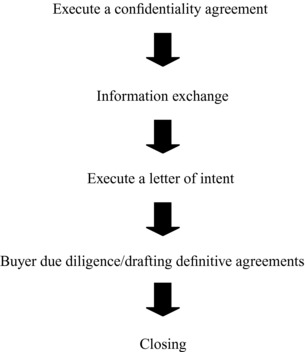

A negotiated transfer is a fairly flexible process since it is dependent on the wishes of the seller. However, Exhibit 32.5 depicts the steps that need to occur for a successful outcome.

EXHIBIT 32.5 Negotiated Transfer: Steps to Completion

Sellers should obtain a confidentiality agreement from the buyer. A confidentiality agreement, also called a nondisclosure agreement, restricts a buyer's use of any information supplied by the seller. Generally the seller or the seller's attorney supplies this document. Once the agreement is executed, the seller supplies information to the buyer, including financial statements, recast items, and whatever else helps the buyer get to the point of making an offer. It is the seller's choice as to whether to state an asking price for the business. The size of the transaction and the orientation of the seller help make this decision. Typically smaller deals employ asking prices; therefore, most business-brokered transactions start with a price. Midsize and larger deals normally do not state a price because synergies may be incorporated into the price, and it is difficult to estimate these accurately in advance.

At some point the buyer may make an offer for the business, usually in the form of a letter of intent (LOI). A letter of intent is generally a legally nonbinding agreement that describes all of the important terms of the deal. Most LOIs contain these key provisions:

- Description of what is being purchased (assets, stock, details)

- Description of what is excluded (specific assets)

- Proposed purchase price with possible adjustments

- Delivery terms of purchase price (cash at close, payment over time, seller note)

- Earn-out provisions (stated with as much precision as possible)

- Due diligence period (scope of the diligence plus time required)

- Conditions to proposed transaction (financing contingencies, other)

- Consulting and noncompete agreements (precise terms)

- Various representations

- Conduct of business until the closing (no material changes)

- Disclosure statements (no public announcements)

- No-shop agreement (exclusive dealing clause)

- Governing law (which state or country governs)

- Closing date

A properly constructed LOI may be 5 to 20 pages long. It is recommended that all deal-killer issues be drafted into the letter. The deal-closing lawyers use the LOI to draft the final purchase and sale documents.

When an LOI is executed the buyer begins the due diligence stage. The buyer generates a due diligence list of required information. This list might be lengthy and will contain financial, operating, and legal questions. The due diligence period may last 60 to 90 days, and this timing should be spelled out in the letter of intent. About halfway through the due diligence period, the closing lawyers begin drafting the closing documents. As these are the final definitive legal agreements, care is taken to ensure that the will of the parties is correctly articulated. Typical closing documents include a purchase and sale agreement, possibly a short-term employment agreement with the seller, a noncompete agreement from the seller, and other agreements such as a real estate lease. Exhibit 32.6 provides the transfer matrix for negotiated transfers.

EXHIBIT 32.6 Transfer Matrix: Negotiated Transfers

| Transfer Methods | Negotiated Transfers |

| Definition | One or more buyer prospects are identified and negotiated with independently. |

| Owner motives | To maintain maximum confidentiality and transfer the business only if the deal is right. |

| Means of transfer authority | An industry of brokers and intermediaries are available to assist the owner, including business brokers, M&A intermediaries, and private investment bankers. |

| Value world(s) | Market value. |

| Capital access point(s) | Most CAPs are available to support a negotiated transfer. |

| Key points to consider | Negotiated transfers often are used for smaller deals, where an owner is a seller only if the deal is right. Either a buyer initiates the discussion with an owner or a broker contacts numerous buyers who have previously registered with the broker. The deal is highly customized and must align owner value and investor value for a successful conclusion. |

EXHIBIT 32.7 One-Step Private Auction: Steps to Completion

PRIVATE AUCTIONS

The dictionary defines an auction as “the public sale at which goods or property are sold to the highest bidder.” Intermediaries have modified the auction concept to sell private companies confidentially. In a private auction, the intermediary attempts to entice a limited number of buyers into a quiet auction setting. Unlike a public sale auction, where the bidders see each other and strategize based on this awareness, the private auction creates a bidding environment. A savvy intermediary orchestrates this process to the benefit of the seller, both in terms of confidentiality and a maximized selling price.

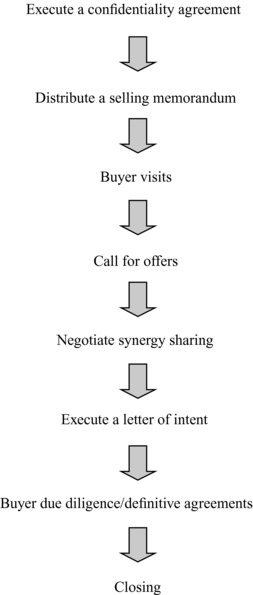

Private auctions may have one or two steps. A one-step auction concurrently encourages interest within a limited group of buyers. One-step auctions are most appropriate where the likely buyers are known prior to the auction. In all likelihood, they are synergistic buyers. Finally, the intermediary does not want to advertise an auction process is being employed for fear that buyers with the best fit will not play.

The one-step private auction typically uses the process shown in Exhibit 32.7.

Several aspects of the one-step private auction are different from the negotiated transfer process described earlier. The auction process generally relies on a selling memorandum to disseminate information to the buyers. This document is created by the intermediary and basically tells the story of the subject company and the deal. The subject's financial statements are usually recast for discretionary and one-time expenses. The intermediary includes whatever information is necessary to enable a buyer to make an informed offer, without giving too much sensitive data away. For example, customer and employee names should not be included in the memorandum. Product-line profitability of the subject might be included as long as no cost-of-sales detail is provided. The intermediary and seller decide what information should be presented in the selling memorandum.

All interested buyers visit the seller within a fairly short period. This ensures buyers receive the same information at approximately the same time. For confidentiality reasons, visits are normally held outside of the seller's facility. If an intermediary is engaged, it is typical for buyers to interact directly with the seller only once prior to offer and agreement.

At some point after the last buyer visit, the intermediary calls for offers. The call may be a phone call, an email, or a letter. The intermediary states the desired format for the response. Depending on the circumstances, a phone conversation between the intermediary and decision maker for the prospective buyer may suffice. In other cases, a term sheet outlining the buyer's offer is warranted. Finally, a more formal letter of intent may be required. The intermediary's goal in the process is to foster competition, receiving multiple offers within the same week accomplishes this mission.

A deal really starts once the first offer is received. Unless one of the buyers makes a preemptive offer, the first-round offers are typically disappointing. A preemptive offer is an attempt to lock out the other bidders with a high purchase offer. While preemptive offers occur too often to be considered urban myths, most of the time the intermediary needs to improve one of several less-than-acceptable offers. Every deal maker has developed methods for dealing with this issue. Some will try to force or coerce a buyer into improving the offer. Intimidating buyers into paying more works well in the movies but not so well in the real world. A better approach is to discover how much more a buyer can afford to pay and still meet return expectations. This can be accomplished if the seller and buyer share synergies created by the deal. In other words, it can be accomplished when the deal is valued in the synergy subworld of market value.

The synergy subworld represents the market value of the subject when synergies from a possible acquisition are considered. Synergy is the increase in performance of the combined firm over what the two firms are already expected or required to accomplish as independent companies. From a valuation viewpoint, synergies are captured mainly from increases in the benefit stream of the combined firm.

A benefit stream may comprise earnings, cash flow, and distributions. This benefit stream is economic in that it is either derived by recasting financial statements or determined on a pro forma basis. Since the synergy subworld signifies the highest value available in the marketplace, the stream reflects the varied possibilities that exist in the market. The benefit stream for this subworld is:

![]()

Recast earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) is adjusted for one-time expenses and various discretionary expenses of the seller. These earnings are measured before interest since the valuation assumes a debt-free basis, and on a pretax basis since the market value world typically does not consider the tax status of either party. This lack of tax consideration is driven by the fact that many private companies are non-taxpaying flow-through entities, such as S corporations and limited liability companies. There are significant differences within the individual tax rates, such that tax rates for other parties cannot be determined with certainty. A pretax basis enables the parties to view the business on a similar basis. The amount of enjoyed synergies represents the synergies that a party can reasonably expect to realize, or receive credit for, in the acquisition. Chapter 7 shows how to analyze synergies in a market valuation setting.

Intermediaries attempt to use the private auction process to maximize synergy sharing on behalf of their clients. This is vital since only the numerator of the value equation can be influenced by the intermediary.

The denominator of the valuation equation is the required rate of return needed by the buyer to compensate for the risk of making a particular investment. Once buyers understand the risk of an investment, they bring this expectation to the deal.

Another way of considering expected investor returns is to take the reciprocal of the buyer's expected rate of return, or capitalization rate, which then becomes a selling multiple. For example, an 18.0% weighted average cost of capital corresponds to an acquisition multiple of 5.6 (1/.18). This is a shorthand way of considering this issue, as the conversion does not incorporate long-term growth. In general terms, this prospective buyer could pay 5.6 times the benefit stream for an acquisition candidate and still meets its expectation. In this case, the buyer is betting that the benefit stream will continue for a minimum of 5.6 years. Increases in the benefit stream over the six years would increase the buyer's overall return.

The capitalization rate is somewhat fixed by a particular buyer, whereas the benefit stream varies with different buyers. Perhaps the following PrivateCo example can demonstrate this point.

Example

Joe Mainstreet has decided to sell PrivateCo. On the suggestion of his lawyer, Joe hires Dan Dealmaker, a private investment banker, to assist in the sale. Dan believes PrivateCo is salable and a one-step private auction is the most suitable marketing process for the company. Dan researches the market and finds 12 prospective buyers for the business. Joe adds three to four companies that have periodically inquired about buying the business.

Dan sends a fact sheet and confidentiality agreement to the 16 companies that comprise the final prospect list. Of course, the fact sheet does not name PrivateCo.

Everything is coded to ensure confidentiality. Ten of the 16 prospects respond with an executed confidentiality agreement. Dan phones the ten to further discuss their acquisition programs and decides to cut three from this list for various reasons. The list is pared to seven.

Dan sends the seven interested parties a selling memorandum. Aside from the normal narrative, Dan recasts PrivateCo's income statement as shown (taken from Chapter 6).

Dan believes the prospects will buy into a recast EBITDA number of around $2.5 million. Some buyers give credit for certain adjustments while others do not. Dan also believes that, on the average, this group of buyers will view the risk of achieving the earnings at about 20%. PrivateCo's industry players pay about five times recast earnings, which further confirms his hypothesis. Multiplying the likely selling multiple (5) by the likely recast EBITDA yields a likely enterprise value of $12.5 million (5 × $2.5 million). Joe will pay off PrivateCo's long-term debt of $500,000 at the close, so Dan Dealmaker is expecting offers of at least $12 million.

Five companies decide to visit. Dan schedules all of the visits within a two-week period, to be held at his own office. Three of the buyers visit PrivateCo's facility at night. Two industry buyers choose not to visit the facility. There are few secrets in PrivateCo's industry. Several weeks after the final visit, Dan calls for offers. Three companies make offers by submitting term sheets. One offer is for $11 million, and the other two offers are for less than $10 million.

Fortunately, Dan is a veteran and knows it is show time. The highest bid comes from a company in PrivateCo's industry that can horizontally integrate Joe Mainstreet's operation into their own. Dan smells synergies. With Joe's help, Dan compiles the next list of probable synergies (taken from Chapter 7).

Dan Dealmaker believes he can get credit from the buyer for about 30% of the total synergies, or $534,000. This increases PrivateCo's benefit stream to about $3 million. Dan employs a proprietary process that he has used successfully through the years to entice the buyer to share these synergies. After another month of hard work, Dan is able to negotiate a deal for about $13.5 million. Here are the numbers.

| Original offer | $11 million |

| Original multiple offered | at 4.5 × recast EBITDA |

| Original recast EBITDA | $2.5 million |

| Ultimate offer | $13.5 million |

| Ultimate multiple offered | at 4.5 × recast EBITDA + shared synergies |

| Ultimate benefit stream | $3 million ($2.5 MM EBITDA + $.5 MM synergy) |

Of course, the deal craters during due diligence over some nitpicking drivel. But none of this should detract from the fine work performed by the hero of this story, the tireless but underappreciated private investment banker.

In this example, the buyer's return expectation does not change during the deal. Only the benefit stream changes to enable a higher purchase price. A real-world consideration: No buyer offers to pay a higher price without being pressured, even if it can afford to. It is the seller's responsibility to employ a transfer process that leverages its strengths so that a buyer will pay the maximum price.

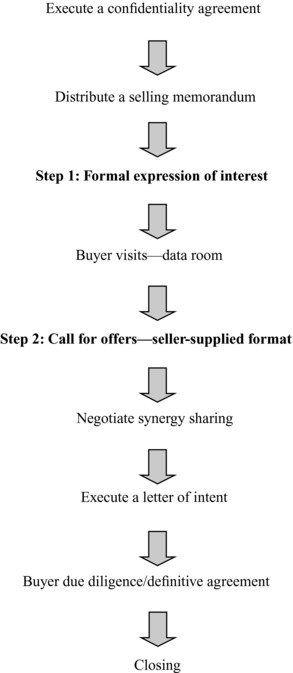

TWO-STEP PRIVATE AUCTIONS

A two-step private auction is a more formal selling process than the one-step auction. A two-step auction process is most useful when the subject is so desirable that a formal auction process will not scare buyers away. Each step of the selling process is staged using deadlines. For instance, once a confidentiality agreement is executed and limited information is shared, the first stage calls for a written expression of interest. Only the top prospects are allowed to continue to the next step. In the second step, the prospects are allowed additional access to more detailed information about the target. Finally, the intermediary calls for a final offer, usually in the form of a formal letter of intent. The intermediary posts all rules for the two-step auction at the beginning of the process, complete with dates of completion for key events.

Exhibit 32.8 contains the transfer matrix for one- and two-step auctions.

EXHIBIT 32.8 Transfer Matrix: One- and Two-Step Private Auctions

| Transfer Methods | One-Step Private Auction | Two-Step Private Auction |

| Definition | This type of auction concurrently encourages interest within a limited group of buyers. | This type of auction uses stages and deadlines to manage a large group of interested buyers. |

| Owner motives | The owner believes only a handful of buyers are synergistic with the company. By approaching only a few buyers, confidentiality should be maintained. | The owner believes the company is highly desirable and is willing to subject the company to market-wide scrutiny. |

| Means of transfer | An industry of brokers and intermediaries are available. | An industry of brokers and intermediaries are available. |

| Authority | M&A intermediaries and private investment bankers | M&A intermediaries and private investment bankers |

| Value world(s) | Market value | Market value |

| Capital access point(s) | Nearly all CAPs are available. | Nearly all CAPs are available. |

| Key points to consider | One-step auctions are appropriate for industry buyers because the buyers are identifiable, synergistic, and paranoid about entering full-blown auctions. | Two-step auctions force an owner to forgo confidentiality in the hope of better offers. This process is suitable for divestitures and absentee owners. |

EXHIBIT 32.9 Two-Step Private Auction: Steps to Completion

EXHIBIT 32.10 Example Expression of Interest Letter

| To Dan Dealmaker:

ABC Industries, Inc. (“ABC”) is pleased to confirm its interest in acquiring the business and assets of PrivateCo. Some of the assets that we would be acquiring include customer lists, trademarks, technology, formulations, process know-how, intellectual property, good work in process (if any), active raw materials, good finished goods, the manufacturing site, etc. Based on the limited information provided to us, our indicative, nonbinding offering price for PrivateCo is $10 million, payable in cash. This value assumes that no cash would be included in the assets to be transferred and that the assets would be transferred on a debt-free basis. The cash to be paid by ABC would be obtained from internal and other sources in the usual course of business. No special financing would be necessary. We also would structure the nonbinding offer to include a maximum earn-out of $5 million payable over a two-year period. The details of the earn-out would need to be discussed, but would be based on the business meeting its sales and EBITDA projections for FY 20X4 and FY 20X5. In making this nonbinding offer, ABC has assumed that fiscal year 20X3 sales for PrivateCo would be approximately $25 million with a recast EBITDA of $2.5 million. Our nonbinding offer has further assumed that ABC, as the purchaser, would acquire the working capital. Our valuation assumed that PrivateCo would meet its sales forecast for the 20X4–20X6 time frame. Without any balance sheet information, ABC had to make estimates for PrivateCo's working capital. ABC feels that we could bring sales and marketing synergies to PrivateCo, and we could obtain cost savings in administration, manufacturing, or raw materials. These synergies were included in our valuation. In general, the ABC associates feel that the acquisition of PrivateCo could bring significant value to ABC. This expression of interest is not to be considered, and is not, a binding offer, and is subject to ABC conducting due diligence as it deems appropriate. ABC is prepared to commence due diligence as soon as practicable for PrivateCo. Attached is a list of ABC's typical due diligence requirements. In any event, ABC shall have no legal obligations to PrivateCo, nor PrivateCo to ABC, unless and until definitive agreements have been executed and delivered. ABC's nonbinding offer is further subject to: (i) the approval of ABC's Executive Committee and its Board of Directors, (ii) the approval by any required regulatory bodies or governmental agencies, and (iii) the negotiation of a definitive purchase agreement between the parties. The submission of this indication of interest is made on a confidential basis. It is understood that neither the fact of this proposal or its terms, nor the identity of ABC as having submitted an indication of interest, will be disclosed other than in connection with the analysis of this proposal by PrivateCo and its advisors or as may be required to be disclosed, in the opinion of PrivateCo's counsel, by law. ABC has made a number of acquisitions with a view to strengthening and expanding its Industrial Widget businesses. PrivateCo could represent an important extension of this strategy. ABC has the managerial experience and the resources to conclude this transaction expeditiously. Very truly yours, Tom Smith, President of ABC |

Exhibit 32.9 depicts the two-step process. There are five important differences from the one-step process.

1. The two-step private auction uses dates and deadlines to move from one-step to the next. Unlike the one-step process, the buyers know they are in a rules-driven auction.

2. The universe of potential buyers is probably larger in a two-step auction. Instead of 5 to 15 prospects as in a one-step auction, there may be dozens of buyers introduced to the deal.

3. Once the buyers sign a confidentiality agreement and receive a selling memorandum, they have a relatively short period of time to submit an expression of interest including the price range they would be willing to pay. Exhibit 32.10 shows an example expression of interest letter. Of course, there are hedges on this value since the buyers have not talked with management on the subject nor reviewed any additional information other than what is presented in the memorandum. Based on the expression, the intermediary picks the top 6 to 10 prospects, who then enter the second step of the auction.

4. The use of data rooms to support buyer visits is an additional difference. Some intermediaries use data rooms with a one-step auction, but they tend to be more prevalent with the more formal two-step process. A data room is just an area, often a digital warehouse, that contains mountains of data that a buyer can review to better understand the subject.

5. After the visits, the intermediary calls for offers. In some cases, the intermediary supplies the offer format for the buyer to use at this stage. The buyer is requested to fill in the price and other terms that are peculiar to their offer.

CLOSING THE DEAL

Closing a deal is usually an extremely difficult undertaking. Seemingly there are dozens of obstacles yet only two variables that promote a closing: the will of the parties. If both buyer and seller are not committed to fighting through the issues, especially those that arise on the day of closing, no deal will happen.

Once a letter of intent is executed and due diligence is mainly completed, the parties negotiate the definitive agreement. This is the legal agreement that contains the legal understanding between the parties. These negotiations are best performed in a team approach, with a lawyer taking the lead but with support from the intermediary, CPA, owner, and other professionals as needed. Issues that typically arise are:

- Representations and warranties by the parties

- Material adverse changes to closing (buyer can terminate the deal if major)

- Indemnity provisions including caps and baskets (amount by which there will be no offset against the escrow)

- Escrow to secure indemnity; possible remedy beyond escrow

- Amount/period

- Survival of representations at least through escrow period, possibly longer

- Conditions to closing for both parties

- Minimum target net worth closing condition, with possible purchase price

- Adjustments based on changes to net worth at the closing

- One-way breakup fee (2%–4% of the purchase price is typical)

- Noncompetes from shareholders

- Employment agreements from key employees

It is not unusual for these negotiations to take several months. A successful tactic is to have weekly conference calls or meetings between the teams so that each issue is dealt with as part of the entire negotiation. Once the definitive agreement and other agreements, such as employment, noncompetes, and lease agreements, are executed, money changes hands and the deal is legally closed.

AFTER THE TRANSFER

This chapter assumes the goal of the owner-manager is to retire as soon as possible after the transfer. If the owner has a strong management team in place, departure may occur soon after the closing. This is another incentive for an owner to build a team. Without a strong team, the owner may need to stay with the company for two to three years after the closing to ensure a smooth transition. Some sellers view this period as equivalent to jail time. The new owner always seems to employ procedures that rub the old owner the wrong way. Owners in a long-term employment agreement position should negotiate a walk-away-without-pay-or-penalty employment agreement just in case they cannot take it anymore.

TRIANGULATION

It is an American dream to sell a business for a bundle and ride off into the sunset. This chapter discusses several strategies to enable owners to realize this dream.

In business, timing is everything. This is certainly true when it comes to business transfer. The timing trifecta occurs when personal, business, and market timing converge. Less-than-perfect solutions usually result if only one or two of the transfer timings are aligned. Since owners cannot control market timing, they must watch market movements.

Outside transfers occur in the open market and are valued in the world of market value. It is the unspoken goal of every owner to achieve a value in the synergy subworld of market value. In order to meet this goal, a company needs to be of sufficient size and complexity. Most companies fall short of this goal but still can be sold in the financial subworld.

Many investment bankers employ a one-step auction selling process and invite handfuls of strategic and nonstrategic buyers. The latter group serves as an insurance policy. Recently a medium-size industrial distributor was sold using this strategy. None of the industry players would share synergies with the seller, so the deal was valued in the financial subworld. The seller instead chose to sell 80% of his company to a private equity group. Rather than leaving the company at the closing, he decided to stay on the job and grow the business to another level. His hope is that the 20% remainder interest eventually will be worth as much as the 80% he received in the original sale. This recapitalization strategy is the subject of Chapter 33.

NOTE