CHAPTER 34

Going Public, Going Private

Less than .1% of all companies in the United States are publicly held. Yet “going public” is the dream of many private business owners. It is like the dream of the sandlot player convinced he will be in the major leagues against all odds. The process of taking a private company public involves offering securities, generally common or preferred stock, for sale to the general public. The first time such securities are offered is generally referred to as an initial public offering (IPO). Some private companies offer public securities to the market, called direct public offerings (DPOs), but they remain private firms after the offering. Other companies become public by merging with an existing public company. Called a reverse merger, this transaction enables a private company to go public more quickly and less expensively than through a traditional IPO.

There are several good reasons to go public. The most likely reason is to raise capital for operational expansion at a lower cost of capital than otherwise possible. Other factors include the ability to use stock as currency for acquisitions, to diversify and liquefy personal holdings, and to burnish a company's reputation. Yet there are equally good reasons why a company should remain private. These include the intrusion of public shareholders into the company's affairs, the demand for short-term financial results, the high costs involved, and the probability that the benefits of going public are overrated. This last point is especially important and often misunderstood.

Most public companies do not enjoy all the benefits of public ownership. For instance, until a public company has a market value of outstanding shares of more than $300 million or so, its shares are thinly traded, and its access to public capital is limited. Since most companies sell only 20% of their shares to the public at the outset, the market value of the company must be more than $1 billion before the full advantages of public ownership are realized. Because the costs of being public often outweigh the benefits, thousands of public companies fall into the should-be-private category, which is the corollary to the could-be-public concept in Chapter 3. A number of should-be-private companies actually go private each year.

There are four primary ways for a private company to go public:

1. A DPO, which is a do-it-yourself IPO of sorts, in which securities are exempted from many of the registration and reporting requirements of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). DPOs take a variety of forms, allow differing amounts of money to be raised within a 12-month period, and place varying restrictions on the investors.

2. An IPO on an American stock exchange.

3. Going public on a foreign exchange, such as the London Stock Exchange's AIM trading market for small business, or the Toronto Stock Exchange's TSX Venture Exchange.

4. A merger with an existing public company, commonly referred to as a reverse merger.

The first part of this chapter discusses DPOs. Next is a review the traditional IPO process, including the players, costs involved, and key points to consider. Then there is a description of reverse mergers. The chapter ends with a discussion of taking public companies private.

DIRECT PUBLIC OFFERINGS

The term direct public offering is almost a misnomer and is couched in confusion. DPOs are all based on amendments and exemptions to federal securities law known as Regulation D, Rules 504–506 and include Rule 147, which also encompass a significant portion of the private placement regulations.

DPOs, as with IPOs, allow the sale of stock or debt instruments to the general public and with some restrictions and disclosure requirements. DPOs allow a company to reach outside its immediate circle of friends, family, and acquaintances to sell stock. There is overlap in the definition and regulation of DPOs with Regulation D private placements. The major distinguishing difference is that Regulation D private placements require a “prior existing relationship” among other restrictions, to sell to investors.

The most common DPO is the Small Corporate Securities Offering Registration, or SCOR, which is a simplified DPO. The SCOR permits the sale of securities to an unlimited number of investors. For this reason, SCOR is known as a registration by exemption, because it is basically a hybrid between a public offering and a private placement, as are all DPOs. Stock sold under a SCOR offering can be freely traded in the secondary market, but it often has a limited float, has no market makers, and is quite difficult to find buyers, which yields limited liquidity and a lower valuation.

SCOR registrations use Form U-7, which is the general registration form for corporations registering under state securities laws. SCOR is designed for use by companies and their attorneys and accountants, who are not necessarily specialists in securities regulation.

Companies filing a SCOR are subject to certain requirements and an application process.

- The U-7 registration form has 50 questions. In some cases, the answers to these questions provide potential investors with adequate information about the company ownership, business practices, intentions, risks, competition, stock allocations, and proposed distributions if the company is already known to the potential investor. Often the lack of detail in the U-7 form about the business deters outside investors and leads to lower valuations.

- Before any stock can be sold, the completed U-7, together with supplemental exhibits including financial statements, needs to be approved by the state securities administrator in each state in which the stock is to be offered. On approval, the U-7 becomes the prospectus or offering circular and may then be photocopied and given to potential investors. An expensive printed prospectus is not required.

- A U-7 can be drafted by company officers, assisted by their attorney and CPA, and submitted for approval.

The offering price must be at least $5 per share in most states, although some states allow $1.1 Moreover, the company may not split its stock or declare stock dividends for two years following the effective date of the registration, except with the permission of the securities administrator in connection with a subsequent registered public offering.

The securities registered and sold are freely transferable and tradable, but the company is limited to raising no more than $1 million in any 12-month period. Due to the offering size and $1 to $5 per share minimum price, a public trading market is unlikely to arise. The Pacific Stock Exchange (PSE) received approval in May of 1995 from the SEC to list SCOR securities, which could have created a market for listed SCOR and other DPO securities. But in 2006, the PSE was merged with the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and the market for SCOR securities remains limited.

The SCOR offering is an early-stage venture financing, using public investors solicited by means of advertising and other general solicitation. If appropriate, the SCOR may be followed at some later stage by other DPOs or a conventional public offering that could result in the development of a publicly traded market. Depending on the state, SCOR may be used to register common or preferred stock, including convertible preferred and options, warrants or rights. After demonstrating that the company will be able to meet debt service, SCOR may be used to register debt securities, including convertible debt.

Under a SCOR offering, a company can advertise for investors and sell securities to anyone who expresses an interest. Obviously, this provides businesses a much-needed tool for raising capital. Small companies have successfully used SCOR to sell stock without using a securities underwriting firm. This method works particularly well for companies with an established customer base or other supportive source of investors.

Other DPOs or related offerings exist that allow companies to raise various amounts of capital on an annual basis include:

- SEC Regulation D, Rule 505, which enables a business to sell up to $5 million in stock in a 12-month period to an unlimited number of accredited investors and up to 35 nonaccredited investors.

- SEC Regulation A offerings, which are “mini public offerings,” and allow up to $5 million raised and bypassing SEC registration.

- SB-1 allows up to $10 million raised.

- SB-2 allows an unlimited amount of securities to be sold in a 12-month period.

Finally, there is an intrastate filing exemption, Rule 147, which allows an unlimited amount of capital to be raised, as long as the stock is sold only in the primary state in which the company does business. Both the investors and the company must reside in the same state under Rule 147.2

Private companies use DPO offerings to access money from investors in a public venue. The issuing company does not become a public company because it uses a DPO. Public companies, a different breed, are covered next.

WHICH COMPANIES ARE PUBLIC?

A company is technically public if it must file public disclosures with the SEC. The federal securities laws require tens of thousands of companies to file reports with the SEC each year. These reports include quarterly reports on Form 10-Q, annual reports (with audited financial statements) on Form 10-K, and periodic reports of significant events on Form 8-K. A company must file reports with the SEC if one of the listed items is true:

- It has 500 or more investors and $10 million or more in assets.

- It lists its securities on these stock exchanges:

- Boston Stock Exchange

- Chicago Stock Exchange

- Cincinnati Stock Exchange

- Nasdaq

- NYSE

- NYSE Amex Equities

- Pacific Exchange

- Philadelphia Stock Exchange

Nasdaq and the NYSE are the largest and best known. Fewer than 8,000 companies are listed on these two national exchanges.3 Due to a consolidation of ownership of the stock exchanges and increased competition for the listings of companies, many changes and lowering of listing standards have occurred recently. New markets have been created to allow the listing of smaller companies in search of public capital, with both NYSE and Nasdaq having alternative markets available for smaller companies.

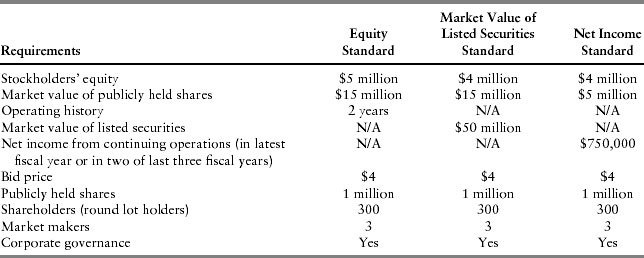

Summarized listing requirements for the Nasdaq Capital Market are shown in Exhibit 34.1. Companies must meet all criteria under at least one of the standards shown in the exhibit.4

EXHIBIT 34.1 Nasdaq Capital Market Initial Listing Requirements

Nasdaq is comprised of several markets, including the Nasdaq Global Select Market, Nasdaq Global Market, and the Nasdaq Capital Market, all with differing listing requirements. As shown in Exhibit 34.1, a company with $5 million stockholders’ equity, a $15 million value of 1 million publicly held shares, and two years of operating history without earnings can be listed on the Nasdaq Capital Market.

The NYSE is more restrictive than Nasdaq in a few key areas, including a minimum trailing earnings requirement of the NYSE and a greater number of initial shareholders. The NYSE also requires both a much larger market value of public float than Nasdaq and wider ownership of the listed firm's shares. Exhibit 34.2 shows NYSE listing requirements.5

EXHIBIT 34.2 NYSE Listing Requirements

| DISTRIBUTION AND SIZE CRITERIA (Must meet all 3 of the following) | |

| Round-lot holders | 400 U.S. |

| Public shares | 1.1 million outstanding |

| Market value of public shares | |

| IPOs, spin-offs, carve outs, affiliates | $40 million |

| All other listings | $100 million |

| Stock price criteria | $4 |

| FINANCIAL CRITERIA (Must meet 1 of these alternative standards: earnings test, valuation, affiliated company, or assets and equity) | |

| Earnings Test | |

| Aggregate pretax income for the last 3 years | $10 million |

| Minimum in each of 2 most recent years; third year must be positive | $2 million |

| OR | |

| Aggregate pretax income for last 3 years | $12 million |

| Minimum in most recent year | $5 million |

| Minimum in next most recent year | $2 million |

| Valuation (Cash Flow or Revenues) | |

| Cash Flow | |

| Global market capitalization | $500 million |

| Revenue (most recent 12-month period) | $100 million |

| Aggregate adjusted cash flow for last 3 years (all 3 years must be positive) | $25 million |

| OR | |

| Pure Valuation with Revenues | |

| Global Market Capitalization | $750 million |

| Revenues (most recent fiscal year) | $75 million |

| Affiliated Company (for new entities with parent or affiliated company listed on NYSE) | |

| Global market capitalization | $500 million |

| Operating history | 12 months |

| Assets and Equity | |

| Global market capitalization | $150 million |

| Total assets | $75 million |

| Stockholders’ equity | $50 million |

INITIAL PUBLIC OFFERING TEAM

An IPO's success depends on selecting and assembling the right team. Exhibit 34.1 depicts the major players. Managers of the issuing company are normally fully engaged in the process. Just feeding the other professionals information is a full-time job for a number of the issuing company's managers. One of the primary differences between a successful and failed IPO is the management team's commitment to the process.

Hiring the investment banker or underwriter is the key initial decision. Aside from selecting an underwriter with access to the marketplace, it is important that this firm also has analysts who follow the industry of the issuing company. It is preferable for the issuing company to develop a relationship with several investment banking firms a number of years prior to the actual underwriting event. Doing this enables enough time to build relationships that are necessary once the IPO process begins. Ultimately, the company selects one investment banking firm to lead the offering.

The next criteria are useful in selecting the appropriate investment banker:

- The underwriter's track record

- Further services offered, such as debt placement and merger and acquisitions advice

- An analyst who understands the industry and is committed to following the company going forward

- The ability to distribute the stock to large institutions or individual investors through its retail arm

- A fair deal regarding the underwriter's compensation

OTC BULLETIN BOARD

The over-the-counter bulletin board (OTCBB) is an electronic quotation system that displays real-time quotes, last-sale prices, and volume information for many over the counter (OTC) securities that are not listed on Nasdaq Stock Market or a national securities exchange. Brokers who subscribe to the system can use the OTCBB to look up prices or enter quotes for OTC securities. Although the National Association of Security Dealers oversees the OTCBB, the OTCBB is not part of the Nasdaq Stock Market.

The issuing company's board of directors normally makes the final choice of a lead investment banking firm. Once an investment banker is chosen, attention can be turned to the particulars of the offering. Particulars include the estimated offering price range for the securities being issued and whether the assignment will be on a firm-commitment or best-efforts basis.

EXHIBIT 34.3 Initial Public Offering Team

With a firm commitment, the underwriter agrees to buy all of the issue and thereby assumes the risk for any unsold securities. The offering company prefers a firm commitment type of offering; this is used most frequently for larger offerings. The commitment is not made until the exact offering price is negotiated, which happens just prior to the effective date of the registration statement. This timing enables the price to be aligned with current market conditions. In a best-efforts offering, the underwriter agrees to use its best efforts to sell the issue but is not obligated to purchase any unsold securities. Best-efforts offerings put the offering company in the untenable situation of not knowing whether the offering will occur. If a company can achieve a best-efforts commitment only, it might be a good indicator that it should remain a private company.

IPO PROCESS

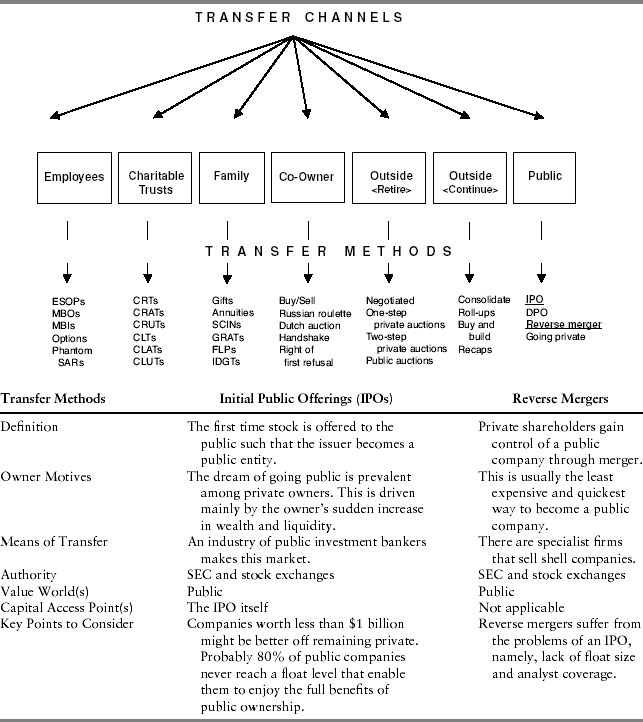

Exhibit 34.3 provides the transfer matrix for IPOs and reverse mergers. Here is a summary of the IPO process. Each of the seven steps involves a tremendous amount of detail. Companies interested in going public should consult with the appropriate lawyers and public investment bankers.

EXHIBIT 34.4 Transfer Matrix: Initial Public Offerings and Reverse Mergers

1. Organizational meeting. The company's IPO begins with an organizational meeting of the various parties involved in the transaction. The agenda of the organizational meeting generally consists of a discussion of the timetable for the offering, the general terms of the offering, and the responsibilities of the various participants.

2. Registration statement. Following the organizational meeting, the company's lawyers begin to draft the registration statement for ultimate submittal to the SEC. The front and back cover pages and the summary and risk factor sections of the prospectus must be written in plain English.

3. Due diligence matters. The due diligence process includes a review of existing agreements to determine whether any security holders have preemptive or registration rights that may be triggered by the offering. If so, the underwriters probably will require that such rights be waived. Similarly, company counsel reviews all other agreements that may affect the offering.

4. Initial filing. The SEC registration statement is filed via EDGAR, the SEC Web site. The company may issue a press release with respect to the filing. If the company elects not to issue a press release, the filing is referred to as a quiet filing. The initial SEC review typically takes 30 to 40 days but may last longer. At the end of the review period, the SEC staff will issue a comment letter containing both legal and accounting comments on the registration statement.

5. Quiet period. The filing of the registration statement commences the “quiet period” that continues until the registration statement is declared effective by the SEC. During this time, company representatives should refrain from providing any information about the company that is not included in the registration statement.

6. Road show. Once the preliminary prospectus is printed and distributed, several representatives of the company, usually the chief executive officer and chief financial officer, and the underwriters embark on a “road show” to major U.S. cities to meet with large institutional investors and market the offering. The road show for an IPO typically lasts two to three weeks. The offering is priced after the completion of the road show.

7. Closing. The date of the closing is determined according to when the offering is priced. If the offering is priced at any time during the day while the market is open, closing will take place three business days later; if pricing occurs after the market closes, closing will be four business days later (T + 3 rule).

Market Maker

A market maker is a firm that stands ready to buy and sell a particular stock on a regular and continuous basis at a publicly quoted price. Market makers are known in the context of the Nasdaq or other OTC markets. Market makers that stand ready to buy and sell stocks listed on an exchange, such as the NYSE, are called third market makers. Many OTC stocks have more than one market maker.

The IPO process requires 6 to 24 months to complete. Bad planning or incorrect advice may cause delays of several months and additional costs. If the deal is not registered properly and executed smoothly, the stock can be underpriced, thereby potentially limiting the amount of equity raised and the market capitalization of the company.

Costs of a Traditional IPO

Performing an IPO is an expensive proposition. As a rule of thumb, it costs about 8% to 10% of the offering proceeds on larger-size transactions and considerably more on smaller transactions, ranging from 15% to 20%, on an all-in basis.6 According to Nasdaq, the expenses shown in Exhibit 34.4 are typical for offerings of $25 million and $50 million.7 But keep in mind that there are considerable pre-IPO expenses involved for accounting, outside consultants, preparation, and positioning of the company. Also, underwriting costs, as a percentage of money raised, can be as high as 18%, in addition to all other costs, with 10% for discounts, 5% accountable expenses, and 3% nonaccountable expenses.8

EXHIBIT 34.5 Estimated Cost of a Traditional IPO

| Item | $25 Million Offering | $50 Million Offering |

| Underwriting commissions | $1,750,000 | $3,500,000 |

| SEC fees | 9,914 | 19,828 |

| NASD fees | 3,375 | 6,250 |

| Printing and engraving | 100,000 | 100,000 |

| Accounting fees | 160,000 | 160,000 |

| Legal fees | 200,000 | 200,000 |

| Blue-sky fees | 25,000 | 25,000 |

| Miscellaneous | 34,200 | 34,200 |

| Nasdaq entry fees | 63,725 | 63,725 |

| Nasdaq annual fees | 11,960 | 11,960 |

| Transfer agent fees | 5,000 | 5,000 |

| Total | $2,400,000 | $4,100,000 |

ADVANTAGES OF GOING PUBLIC

There are numerous advantages to going public. Some of the more important are:

- Access to long-term capital. One of the biggest advantages to going public is the ability to access the favorable financing terms in public capital markets. Public markets are larger, more liquid, and less costly than private capital markets.

- Established value. A public company is valued on a daily basis. This is helpful for a number of reasons, including the ability to use public stock as currency in acquisitions, diversification of owner's estate, liquidity, and the ability to use stock as loan collateral.

- Ability to attract key personnel. Employee incentive and benefit plans are more flexible and sophisticated for public companies. Stock options and stock appreciation rights are useful tools for attracting, motivating, and rewarding employees.

- Public awareness. Every shareholder is a potential customer. Many customers prefer to deal with public companies because of the perception of financial strength that often accompanies these firms.

DISADVANTAGES OF GOING PUBLIC

The disadvantages of going public are important to understand. Some of these are:

- Lack of operating confidentiality. All of the public disclosures give the competition access to information that a private company keeps secret. Some examples are compensation and holdings of officers, detailed financial information, borrowings, and major customers are all available to the public.

- Loss of management control. At some point the management may lose legal control of the public company. Since many private owners tend to be control-oriented, this loss of control may be hard to handle.

- Pressure for short-term performance. Meeting quarterly expectations is a far cry from living in the luxury of the long-term perspective a private owner can take toward the business. Because the report card is so frequent, the manager of a public company spends a large amount of time selling the investment potential of the company rather than managing the company.

- Different accounting and tax issues. Private owner-managers are driven to minimize reported earnings and thus taxes whereas public managers desire to maximize earnings. A public company's financial statements are always audited and must conform to generally accepted accounting principles. Additionally, the public company must follow all SEC rules for accounting and disclosure.

- Costs of being public. The initial costs of going public are enormous. The ongoing costs are substantial.

- Potential liability. Officers of public entities must follow securities laws, including the Sarbanes-Oxley requirements. Officers are also subject to possible insider trading charges.

- Lock-up period for insiders. Owners and pre-IPO stockholders of the company after going public will more than likely not be able to sell their stock for a period of time. A typical lock-up period is four to six months.

- Potential undervaluation. Despite the best of intentions and execution, in going public, a private company faces obstacles to getting its story and information disseminated. Unless it has been a highly visible and well-promoted company prior to going public, its acceptance by the investment community may not reflect the company's true value. Timing and uncontrollable events also can diminish value to a significant degree.

- Sarbanes-Oxley compliance cost. According to one survey that included 168 “accelerated filers”—companies with market capitalizations above $75 million—total average cost for Section 404 compliance was $1.7 million. The survey also revealed that total audit fees for U.S. filers averaged $3.6 million. These costs represent a major loss of value when a price/earnings ratio is applied.9

GOING PUBLIC KEY POINTS TO CONSIDER

Going public is a monumental decision with many related issues to consider, not the least of which is the motivation of the particular private owner. Why go public? Unless there are several specific goals that cannot be achieved as a private entity, the company should not go public. A few more points to consider are:

- Size matters. The size of the float matters. If a public company does not have hundreds of millions of dollars in float, it probably does not gain full access to the benefits of being public. Other companies are less likely to accept its stock as currency in acquisitions. The bond market may not be available. The stock may be too thinly traded to use effectively for employee benefit purposes. Further, stock analysts may not follow the stock.

- The exchange matters. Most public companies are not listed on a national exchange; rather, they are exchanged OTC or listed on a minor exchange. Many small-cap stocks are caught in financial purgatory. They cannot achieve sufficient orbital velocity to get to heaven, but they perform too well to sink to the depths. Unless a company qualifies for listing on a national exchange, owners may regret going public.

- Shared vision. In order to go public, the entire management team must share a corporate vision. This cannot be only one person's vision and be successful. Public companies require management depth because the team faces new responsibilities and new challenges. Transitioning from an executive in a private company to an executive in a public company is one of the more difficult metamorphoses in the business world.

- Earnings growth. To be a successful public company, it is necessary to have both a track record and forecast for high earnings growth. The stock market punishes companies that fail to meet their forecast or that experience average or no growth.

- Market timing. The market for IPOs runs in cycles. It is difficult to achieve a good price for an IPO stock in a down cycle. It is probably better to delay going public until the market is more receptive.

- Benefits versus costs. Owners must ask: Do the benefits of being a public entity outweigh the costs of achieving this status? Unless the answer is clear-cut, the owner probably is better off staying private.

The decision to go public should not be made in isolation. Fortunately, thousands of lawyers and investment bankers can assist in this discovery process.

GOING PUBLIC ON FOREIGN EXCHANGES

Foreign exchanges such as AIM or the TSX Venture Exchange have differing advantages, disadvantages, and costs from those of American exchanges. They should be thoroughly researched and evaluated as alternatives for even American companies considering going public. Since inception in 1995, more than 2,200 companies have had an average of over $20 million raised on AIM.10 TSX Venture Exchange is a public venture capital marketplace for emerging companies. As of this writing, the exchange had listed 2,364 companies with an average market capitalization of $25.7 million.11 It is of paramount importance to retain experienced legal, accounting, and investment banking expertise in connection with foreign exchange IPOs.

REVERSE MERGERS

The second method of going public is through a reverse merger. A reverse merger is a transaction whereby private company shareholders gain control of a public company by merging it with their private company. The private company shareholders receive a substantial majority of the shares in the public company (normally 80% to 90% or more) and control of the board of directors. The public corporation is called a shell. All that exists of the original company is the corporate shell structure and shareholders. The transaction in which a private company is taken public in a reverse merger can be accomplished quickly because it does not go through a review process with state and federal regulators. The predecessor public company has already completed the process.

“PINK SHEETS”

The pink sheets—named for the color of paper on which they have historically been printed—available by subscription from the National Quotation Bureau are daily listings of bid and ask prices for OTC stocks not included in the daily Nasdaq OTC listings. “Pink sheet” companies typically do not meet listing requirements.

Upon completion of the reverse merger, the name of the shell company usually is changed to the name of the private company. If the shell company has a trading symbol, it is changed to reflect the name change. If the shell company has no symbol, an application for a symbol usually is made to the Nasdaq bulletin board. The bulletin board has no financial requirements. A listing will be granted if the affairs of the company are in order and the company answers the questions posed by Nasdaq.

If the shell company is listed on the bulletin board, the registered shares can continue to trade. The company can do a private placement immediately. In order to offer new shares to the public, the newly combined public company must first register the shares with the SEC. This process takes three to four months and normally requires filing a registration statement with the SEC.

Mechanics of a Reverse Merger

There are many details involved in successfully concluding a reverse merger. A summary of the main steps is presented next.

First, a public vehicle normally acquires 100% of the outstanding stock of the private company in consideration for issuing to the private shareholders a negotiated number of restricted shares in the public company. The private company generally continues to operate as a wholly owned subsidiary of the public holding company.

Second, following the previous transaction, the total shares held by the private company's shareholders usually will equal a majority of the total outstanding stock in the public holding company. The officers and directors of the public company resign at the closing, and the officers and directors of the private company now manage the public company and continue to operate the wholly owned subsidiary.

The total time required for a private company with audited statements to become public via this process is approximately three to eight weeks. The fees involved in a reverse merger vary on a project-by-project basis and are dependent on many variables, including the type of vehicle used. The cost of acquiring a public shell ranges from $100,000 to $1 million, in addition to 5% to 40% of the stock in the company after merger.12 Legal and accounting fees are additional expenses.

The primary advantages to going public via a reverse merger are speed to market and limited expense. A reverse merger may save 12 months and millions of dollars of costs that would be incurred in a traditional IPO. All of the disadvantages of being a public company mentioned earlier apply to an entity formed through reverse merger with one major addition: It is highly unlikely that security analysts will follow a company that enters the market through a reverse merger. If the market movers do not get behind a public company, it loses many of the benefits of being public.

GOING PRIVATE

A company goes private when it reduces the number of its shareholders to fewer than 300 and is no longer required to file reports with the SEC. About 500 companies each year deregister from a major exchange, or “go dark,” as it is called, when their shareholders of record fall below 300 (or 500, if assets total less than $10 million). For many of these companies, total shareholders may number in the thousands. However, since recorded shareholders fall below the threshold, the company deregisters and is no longer a public entity.

A number of transactions can result in a company going private, including:

- Another company or individual makes a tender offer to buy all or most of the company's publicly held shares.

- The company merges with or sells the company's assets to another private company.

- The company can declare a reverse stock split that not only reduces the number of shares but also reduces the number of shareholders. In this type of reverse stock split, the company typically gives shareholders a single new share in exchange for a block of 10, 100, or even 1,000 of the old shares. If a shareholder does not have a sufficient number of old shares to exchange for new shares, the company usually pays the shareholder cash based on the current market price of the company's stock.

Athough SEC rules do not prevent companies from going private, the SEC does require companies to provide information to shareholders about the transaction that caused the company to go private. The company may be required to file a merger proxy statement or a tender offer document with the SEC.

SEC rules require public disclosure of the reasons for going private, alternatives the company may have considered, and whether the transaction is fair to all shareholders. The rules require disclosure of any directors who disagreed with the transaction and why they disagreed or abstained from voting. The company also must disclose whether a majority of directors who are not company employees approved the transaction.

Going-private transactions require shareholders to make difficult decisions. Some states have adopted corporate takeover statutes to protect shareholders and provide shareholders with dissenter's rights. These statutes provide shareholders the opportunity to sell their shares on the terms offered, to challenge the transaction in court, or to hold on to the shares. Once the transaction is concluded, shareholders may have a difficult time selling their retained shares because of a limited trading market.

HOW TO GET DELISTED FROM NASDAQ

There are several ways to get delisted from Nasdaq. Some of the key ways are listed next.

- The subject is taken over.

- A company can be delisted if its stock falls below a minimum trading price for a specific period of time and the company does not meet one of the other minimum standards.

- Once a company's stock price falls below $1 per share, it can be delisted solely based on its stock price. If a company's stock trades below $1 for 30 consecutive trading days or six weeks, Nasdaq will issue a deficiency notice. If during that 30-day period the stock climbs above a buck and then slips below it again, the clock is reset. In any case, the deficiency notice warns the company that it has 90 calendar days to bring its price up to $1 for 10 consecutive days. The company may accomplish this through various actions, such as a merger, acquisition, or a significant transaction or order with another company. If the company is unsuccessful, it could end with a delisting.13

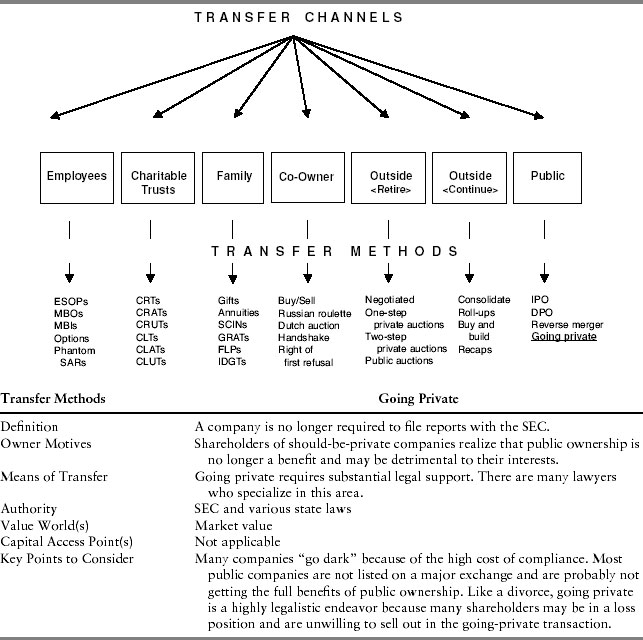

Exhibit 34.6 displays the transfer matrix for going-private transactions.

EXHIBIT 34.6 Transfer Matrix: Going Private

GOING PRIVATE KEY POINTS TO CONSIDER

Going private may be an even more legalistic transaction than going public. This is because going private transactions exclude some shareholders from continuing to hold equity. The major risk is that shareholders may claim unfair treatment by the acquiring party. As a result, going-private transactions must be structured to prevent the inherent danger that the control group will, whether intentionally or not, treat itself more favorably than the outsider group. The next points should be considered prior to taking the first step.

- The transaction must be entirely fair. The price paid and the procedures used must be considered fair to an impartial observer.

- The higher the premium paid for the outsiders’ stock, the less likely a shareholder lawsuit will result.

- SEC disclosure rules must be followed. The SEC requires the filing of a number of public disclosures. For instance, one report requires the proponents of a going-private transaction to explain publicly why they believe the transaction is fair.

- An external fairness opinion is needed. Those seeking to take the company private should engage a nationally known investment banking firm to perform a third-party fairness opinion. This is something of an insurance policy that may further discourage lawsuits.

- A law firm that specializes in going-private transactions is needed.

- Even if all rules are followed, there is a good chance that litigation will result. Some outside shareholders may have lost substantial money and wish to recoup their losses in court. Those taking companies private will not be disappointed if they anticipate litigation. The key is to prepare for it.

Thousands of public firms should be private companies. Only a small percentage of companies that go public achieve the critical mass necessary to make the decision worthwhile. Much like divorcing a business partner, the going-private process is certain to involve lawyers with all of the nastiness and cost associated with a divorce.

TRIANGULATION

An IPO signals the close of the private business spectrum but launches the public value world, as described in Chapter 14. Public markets have authorities and defined processes by which to value interests. Buyouts show that stock prices change based on perceptions of synergies and control. In fact, many of the same variables that drive private value also dictate public pricing.

As they take a company public, private owners trade the anonymity and private ownership control for the magnifying glass of the public markets. Many private owners go public because they believe private markets will not yield enough growth capital, at a reasonable dilution, to support their company's growth needs. Others go public because they would prefer to sell their business for double-digit multiples rather than the single digits the private markets will bear. Whatever the motivating cause, a relatively small percentage of public companies realize the ultimate goal of high liquidity and sustained wealth generation.

By going private, a company moves from the public value world to a private value world, probably the financial subworld of market value. Many of these should-be-private companies actually go private because they have been valued as a private company despite their public stature. Without an increased valuation, high level of liquidity, or active access to low-cost capital, there really is little reason to be a public entity. For these reasons, plus the higher costs of being public caused by adherence to the Sarbanes-Oxley law, thousands of smaller public companies will continue to go private in the coming years.

NOTES

1. Office of Securities, State of Maine, www.maine.gov/pfr/securities/small_business/scor.htm

2. www.sec.gov.

4. Nasdaq: http://listingcenter.nasdaqomx.com/assets/nasdaq_listing_req _fees.pdf.

5. New York Stock Exchange Web site: www.nyse.com/regulation/nyse/1147474807344.html.

6. www.referenceforbusiness.com.

10. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternative_Investment_Market.

11. en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TSX_Venture_Exchange.

13. NASDAQ: http://listingcenter.nasdaqomx.com/assets/nasdaq_listing_req_fees.pdf.