CHAPTER 8

Fair Market Value

The fair market value (FMV) world hypothetically embodies the value of a business interest. In terms of standards and process, FMV is the most structured value world. Examples include estate and gift appraisal, tax court cases, and the valuation of employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs). In some states, FMV is also the standard of value for equitable distribution cases. Finally, since FMV is so well established, it is often the default value world. Yet it is not the correct world in every valuation situation.

Fair market value is defined as:

The price at which the property would change hands between a willing buyer and a willing seller when the buyer is not under any compulsion to buy and the seller is not under any compulsion to sell, and both parties have reasonable knowledge of relevant facts. The hypothetical buyer and seller are assumed to be able and willing to trade and to be well informed about the property and concerning the market for such property.1

The “price” in the definition implies the value is stated in cash or cash equivalents. The “property” is assumed to have been exposed in the open market for a period long enough to allow the market forces to establish the value. The “willing buyer and seller” assumes an equal motivation between the hypothetical, but rational, parties. Finally, the derivation of FMV should follow a process that yields a likely point-in-time value, not a range of values. This value is concerned with the financial capacity of the subject without regard to possible acquisition synergies.

A snapshot of the key tenets of the fair market value world is provided in Exhibit 8.1.

EXHIBIT 8.1 Longitude and Latitude: Fair Market Value

Like the other value worlds, FMV relies on a rigorous process to determine value. In fact, the world of FMV is the most cohesive and fully developed of the value worlds. There are highly specific purposes for these appraisals, and each entails a specific process and set of standards. FMV appraisals are used to establish value in estate and gift valuation, tax court cases, and the creation and updates for ESOPs.

The authorities in this world include the powerful Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and the tax courts, among others. The weight of these authorities, their legitimacy, and the strength of their influence create an orderly world with strict boundaries.

Since FMV is used in a legal environment, standardization of the process is fairly rigid and especially important. The path toward industry standardization really began in 1981, with the publication of Valuing a Business.3 In this seminal book, Shannon Pratt defined the FMV process with a level of detail and precision unknown before.

Due to the work of Pratt and others, valuation has become a career path. Thousands of business appraisers now make their living performing valuations in the world of FMV. The sophistication of business appraisal requires that only that well-qualified, certified appraisers should be generating fair market valuations.

APPRAISAL ORGANIZATIONS

Several professional appraisal organizations grant certification to appraisers and provide education. Exhibit 8.2 describes these societies and lists the main certifications that each provides.

EXHIBIT 8.2 Appraisal Organizations

| Society | Main Certifications |

| Institute of Business Appraisers (IBA) | Accredited by IBA (AIBA) |

| Certified Business Appraiser (CBA) | |

| Business Valuator Accredited For Litigation (BVAL) | |

| American Society of Appraisers (ASA) | Accredited Member (AM) |

| Accredited Senior Appraiser (ASA) | |

| National Association of Certified Valuation | Accredited Valuation Analyst (AVA) |

| Analysts (NACVA) | Certified Valuation Analyst (CVA) |

| American Institute of Certified Public | Accredited in Business Valuation (ABV) |

| Accountants (AICPA) |

The various organizations use differing criteria to certify members. The organizations require candidates to pass written examinations, but only the IBA and ASA require a candidate to submit valuation reports for peer review before certification. References in this book to “certified” business appraisers apply to the main certifications listed in Exhibit 8.2.

Only accredited or certified business appraisers should be engaged for FMV appraisals. The appraisal body of knowledge is too sophisticated for noncertified appraisers to keep up. Further, many appraisers now specialize in certain areas of FMV. For instance, some appraisers only perform ESOP appraisals. Others specialize in family limited partnership appraisals. Appraisal organizations can help sort through the universe of specialized, certified appraisers.

The issue of appraisal “shelf life” comes into play, especially with regard to estate planning issues. Many shareholders gift shares of stock to children and grandchildren each year in an effort to reduce their estates. These gifts should be supported by an FMV appraisal. To be prudent, the subject should be appraised annually. Many shareholders have the stock appraised every few years or even use book value as the basis for the appraisal. This practice is not recommended because of possible IRS reviews and challenges. Most appraisers reduce their rates for annual updates after the first year.

Finally, a client may request to review the appraisal in draft form prior to final issuance. This review may clear up any factual errors or misstatements. Many appraisers do not grant this request until fully paid because they fear clients will not pay once they see the value conclusion. It is not appropriate, however, for clients to insist on interpretive changes to the draft that might improve their positions. Certified appraisers cannot advocate a client's position; rather, they can advocate only their own work.

BUSINESS APPRAISAL STANDARDS

To support business appraisers, each organization has developed and published appraisal standards. These standards provide much of the structure for the practice of valuation. The IBA standards are contained in their entirety in Appendix C. Some of the more important tenets of these standards are summarized here.

- Standard One: Professional Conduct and Ethics. Appraisers must judge whether they are competent to perform assignments. Aside from acting professionally, appraisers cannot use rules of thumb or software programs as surrogates for individual competence. Appraisers must maintain strict confidentiality and have no contemplated interest in the property being appraised. Nonadvocacy is considered to be a mandatory standard of appraisal. The end product of the appraisal must be supportable and replicable. The amount of or method for calculating the appraisal fee must be stated. Finally, certification is extended to individuals, not firms.

- Standard Two: Oral Appraisal Reports. Oral reports are permitted only when ordered by the client. The appraisal should be followed by a written report that presents the salient features of the oral report.

- Standard Three: Expert Testimony. Appraisers should not take any position incompatible with the appraiser's obligation of nonadvocacy. Mandatory content, such as the standard of value, must be stated, and the appraiser must disclose any extraordinary assumptions or limiting conditions.

- Standard Four: Letter Form Written Appraisal Reports. Letter opinions are acceptable as long as they conform to all applicable business standards. Once again, there is mandatory content required. These include proper client identification, stated standard of value, appraisal use, the effective date of the appraisal, the preparation date, the report's assumptions, and limiting conditions and special factors that affect the opinion of value. The letter report must contain a value conclusion, which can be a specific opinion of value or a range of values.

- Standard Five: Formal Written Appraisal Reports. A comprehensive report should detail: distribution, purpose (stated standard of value), function, effective date, date of report preparation, assumptions and limiting conditions, and other factors that combine to make an acceptable report.

- Standard Six: Preliminary Reports. Under certain circumstances, a preliminary report may be issued; however, limitations on the use of the report must be stated by the appraiser.

As this overview indicates, the guidelines for professional business appraisal are direct and available. Aside from the individual organization standards, such as the IBA or ASA, there exists the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP). The USPAP standards are maintained by the Appraisal Foundation and pertain to real estate, personal property, and business valuation. Most business appraisers follow the USPAP standards in transactions involving federal regulations. Any appraisal performed for tax purposes, such as stock gifting or the appraisal of a family limited partnership, should follow the USPAP standards. Readers are encouraged to review the complete standards prior to engaging a business appraiser or reviewing a work product.

FAIR MARKET VALUE PROCESS

Like the other value worlds, the FMV world has a distinct process by which to derive value. This world is quite structured with standards and approaches, since the process must be replicable across a broad array of appraisal needs. The seven-step FMV process is:

1. Define value premise (value to be determined as going concern or liquidation).

2. Determine size of the subject interest to be valued (see Exhibit 8.3).

3. Consider all elements of Revenue Ruling 59-60.

4. Use only three broad approaches—income, market, and asset—for generally accepted business appraisals.

5. Employ a number of different methods, based on the facts and circumstances of the valuation.

6. Determine if any discounts or premiums need to be applied to the unadjusted indicated value.

7. Derive a value conclusion.

Professional business appraisers must consider several other elements to meet the requirements of the standards. Some of these elements are proper identification of the client, stated value world (standard of value), effective date of the report, and contingent and limiting conditions of the report. For the purposes of this chapter, only these seven steps are discussed in detail.

Step 1: Define Value Premise

A going-concern value is the value of a business enterprise that is expected to continue to operate into the future. The intangible elements of going-concern value result from factors such as a trained work force, a customer list, an operational plant, and the necessary licenses, systems, and procedures in place. Liquidation value, however, is the net amount realized if the business is terminated and the assets are sold piecemeal. Liquidation can be either orderly or forced.

The selection of the correct premise of value is critical in determining an appropriate fair market value. Generally the appraiser considers the highest and best use of the subject's assets to determine a value premise, particularly for an enterprise appraisal. Ultimately the use of the appraisal helps determine the premise. For instance, an appraisal to support a reorganization or bankruptcy proceeding most likely presumes a liquidation premise. Likewise, if the subject is highly profitable and this is expected to continue, the likely value premise is as a going concern.

The reader can assume all discussions in this book center around going-concern values, unless otherwise stated.

Step 2: Determine Size of the Subject Interest to Be Valued

This second step in any fair market valuation is to determine what is being valued. The difference in value between a control interest and a minority interest in private companies is discussed in previous chapters. The levels of ownership concept is introduced in Chapter 4 to describe four levels that apply to the private business interest: enterprise, control, shared, and minority. These four levels apply to most value worlds. The world of fair market value, however, has its own levels, which are similar but different from those in Chapter 4. A primary difference is the reliance on public data in the FMV process to derive private values.

EXHIBIT 8.3 Levels of Fair Market Value

Exhibit 8.3 shows the levels of FMV, with references to the direct and indirect information, used to derive values.4 Direct observation means the value level is determined by direct reference to actual comparable data. Direct observation for the financial control level uses a private transactional database of actual private enterprise transactions. Indirect observation refers to valuation methods using indirect estimates of the value. For instance, by capitalizing the subject's earnings, which is an indirect reference to what the market should be willing to pay for the subject's earnings stream, one may derive a financial control value.

Strategic control value is the value of 100% of the company based on strategic or synergistic considerations. As such, this level of value should reflect both the power of controlling the firm plus the added value arising from operational synergies. This value can be observed directly by reference to strategic/synergistic transactions or indirectly by grossing up a financial control value by a strategic control premium. Strategic control premiums represent the amount beyond pro rata value an investor will pay for control plus the amount of synergies credited to the subject's shareholders.

Financial control value represents the value of 100% of the enterprise based on financial returns. As such, this value should reflect the value the control holder exercises, especially in terms of financial policy control. Control value can be obtained directly by reference to other change of control transactions. A variety of databases contain transactions. Control value can be found indirectly by grossing up a minority interest publicly traded stock price by a financial control premium. Financial control premiums represent the amount beyond pro rata value an investor will pay for control. Although acceptable in the valuation standards, it is generally not proper to derive a control value by applying a control premium to a publicly traded stock price. There are now enough control transactions, both for public and private transactions, to derive control value directly.

The next level is marketable minority interest value. This level does not typically exist in the private value worlds. It represents the value of a minority interest assumed to be tradable in the marketplace. This level is attributable to publicly traded securities. This freely marketable level can be obtained either by reference to a comparable publicly traded security or by a capitalization or discount rate from a buildup method. The appropriate rate is built up through use of the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) or other technique, by using public securities data. This level can be determined indirectly by applying a minority interest discount to a control value. As is explained later, minority interest discounts are determined relative to control premiums by using this formula: 1–[1/(1+ Control Premium)]. Minority discounts reflect a lessening of the position due to the lack of rights typically associated with a minority position, as discussed in Chapter 4.

The lowest level is the nonmarketable minority interest value. This level reflects the value of minority interests in private businesses for which there is no active market. Holders at this level also lack control over the company's financial and operating policy. Since there is no active market for private minority interests, this level cannot be obtained by direct reference. It can be obtained indirectly by applying a lack of marketability discount (LOMD) to the marketable minority interest value. A LOMD represents the amount deducted from an equity interest to reflect lack of marketability. The determination of these discounts, relative to the restricted stock and pre–initial public offering (IPO) studies, is discussed in Appendix A. It is also possible to obtain value at this level by applying successive minority interest discounts and LOMDs to a control value.

The levels of FMV chart is important because it reflects what is being valued in this world from a top-down perspective. All appraisals in the FMV world fit somewhere in this chart, and value is derived by applying direct and indirect methods described earlier. Once the what-is-being-appraised question has been answered, the next step in determining FMV begins.

Step 3: Consider All Elements of Revenue Ruling 59-60

More than 40 years ago, the U.S. Treasury Department outlined procedures for determining fair market value. Revenue Ruling 59-60 remains the main guide to determine the fair market value of private business interests. Exhibit 8.4 summarizes the revenue ruling's key points. The IRS lists eight “factors to consider” but proclaims that these should not be considered all-inclusive, without giving further guidance as to what else should be considered.

EXHIBIT 8.4 Revenue Ruling 59-60: Summarized Factors

|

1. The nature of the business and the history of the enterprise from its inception 2. The economic outlook in general and the condition and outlook of the specific industry 3. The book value of the stock and the financial condition of the business 4. The earning capacity of the company 5. The dividend-paying capacity of the business 6. Whether the enterprise had goodwill or other intangible value 7. Sales of the stock and the size of the block to be valued 8. The market price of stocks of corporations engaged in the same or a similar line business having their stocks traded in a free and open market, either on an exchange or over the counter |

There is considerable room for judgment within these factors. For example:

- The earning capacity of a business is the future profit picture of a business ignoring extraordinary factors as well as cyclical and seasonal earnings changes.

- Prior transactions in the ownership of the company's stock are considered relevant as a guide if they occurred within the last two years or so of the appraisal and met the FMV standard of value.

- Minority interests (stock positions of less than 50% of the total outstanding shares) can be discounted substantially due mainly to the inability to control finances of the company. In some cases, small interests have been discounted by 70% to 90% in comparison to the control position.

- When comparing private companies to public companies, a LOMD is appropriate because private companies have no ready market for selling their stock. This discount is determined on a case-by-case basis but has averaged in the 35% to 40% range in many important court cases.

- The dividend-paying capacity of a business is generally considered a less important factor in determining value now than when the revenue ruling was drafted. For the most part, private companies do not routinely distribute dividends due to the tax code. A typical private owner attempts to minimize corporate income tax payments while trying to maximize personal wealth. Dividends do not help the shareholder achieve this goal. Most appraisers tend to rely on the earning capacity of the business in lieu of dividends distributed as a determinant of value.

- There has been a considerable effort by valuation writers and appraisers to look to the public securities markets for valuation guidance for private business interests. This is understandable since there is ample data from more than 30,000 public companies. As argued in Chapter 2, however, this public-to-private method is not always relevant. Private transactions are typically more relevant than public security information for valuing private interests.

The next step in the appraisal process considers which valuation approaches to apply.

Step 4: Use the Three Broad Approaches

Nearly all appraisals in the FMV world employ three broad valuation approaches: income, asset, and market. These approaches form the framework of the valuation determination. The three approaches are like three legs of the appraisal table. Since the approaches are interrelated, all three need to be considered in a FMV appraisal, or the three-legged table does not stand. Each approach is defined in this way:

- Income approach. Uses methods that convert anticipated benefits into a present value.

- Asset approach. Uses methods based on the value of the underlying assets of the business, net of liabilities.

- Market approach. Uses methods that compare the subject to similar businesses, business ownership interests, securities, or intangible assets that have been sold.

The approaches may seem independent, but they are interrelated. The income approach requires a rate of return used to discount or capitalize the income. The marketplace drives these rates. All comparative valuation approaches relate some market value observation to either some measure of a subject's ability to produce income or to a measure of the condition of its assets. The asset approach uses depreciation and obsolescence factors that are based on some measure of market values of assets.

Business valuation standards require appraisers to utilize all three approaches in the valuation, or they must explain why an approach is omitted. It is up to the appraiser's judgment whether to incorporate the individual approach in the final value conclusion. The appraiser in the FMV world selects appropriate methods that best fit the circumstances of the appraisal, then reconciles the results to derive a final value conclusion.

Step 5: Employ Appropriate Methods, Given the Facts and Circumstances of the Valuation

A number of valuation methods are available within each approach. For instance, the capitalization of earnings method may be chosen within the income approach, or the net asset value method within the asset approach. Appraisers choose methods appropriate to the circumstances of the appraisal. Some of the more common methods used in the FMV world are:

| Approach | Method | Appropriate to Use When… |

| Income | Discounted future earnings | Income is largely realized in the future. |

| Capitalized earnings | Income is stable or evenly growing. | |

| Asset | Net asset value | Substantial value difference between book value and fair market value of assets. |

| Often used for capital-intensive business. | ||

| Market | Guideline publicly traded company | When the subject is a large private company comparable to a publicly traded company. |

| Private company transactions | When the subject is similar to companies sold in private transactions. |

There are a number of methods available other than those just listed. The next decision an appraiser makes is whether to employ discounts or premiums to the unadjusted indicated value generated by a particular method.

Step 6: Determine If Any Discounts or Premiums Should Be Applied to the Unadjusted Indicated Value

Each method generates an indicated value before adjustments, called an unadjusted indicated value. The adjustments may increase or decrease the value determined in the step. These adjustments take two primary forms: premiums or discounts. As Exhibit 8.3 shows, premiums and discounts may be necessary to adjust the indicated value to the correct value level of the subject interest. Some of the possible premium and discount adjustments are:

- Control premiums

- Minority discounts

- Lack of marketability discount

- Key person discount

- Nonvoting discount

The various methods yield indicated values at different levels. Exhibit 8.5 shows a number of methods as well as the type of value generated.

EXHIBIT 8.5 Value Type Generated by Different Methods

| Method | Control/Minority | Marketable/Nonmarketable |

| Discounted future earnings | Control or minority | Marketable or nonmarketable |

| Capitalized earnings | Control or minority | Marketable or nonmarketable |

| Net asset value | Control | Nonmarketable |

| Guideline publicly traded | Minority | Marketable |

| Private company transactions | Control | Nonmarketable |

If the net asset value method is used, the indicated value is on the control/nonmarketable level of value. Likewise, the guideline publicly traded method yields a minority/marketable indicated value. Depending on the level being valued, a premium or discount may be needed. A brief review of premiums and discounts helps focus this discussion.

Control Premiums

Control premiums represent the amount an investor is willing to pay for the rights of control, as opposed to the minority position. The rights of control, such as setting distributions/dividends, electing board members, making acquisitions or divestitures, and so on, are so important that a control premium is intuitive. There is a way to measure control premiums. Studies by Mergerstat Review, a publication that measures control premiums, show the average control premium paid in the past ten years has typically been in the 8% to 33% range, with an average of 18%.5

The control premiums measured by Mergerstat involve only public companies. Control premiums are generally used to increase an unadjusted indicated value, which was derived from a comparison to the public securities market in the guideline publicly traded method.

Minority Discounts

A minority discount is a reduction from the control value reflecting a lack of control that a minority holder suffers. If a control premium is intuitive, then it follows that the minority position should be discounted. In fact, one way to determine a minority discount relies on knowing the appropriate control premium:

![]()

By way of example, assume the appraiser believes a 30% control premium is appropriate in an appraisal. The corresponding minority discount is:

![]()

By reference to the 30% control premium, there is an implied 23% minority discount. Quite often appraisers use this formula with the Mergerstat data to derive minority interest discounts.

Lack of Marketability Discount

The LOMD is the amount or percentage deducted from the value of a marketable ownership interest to reflect the relative absence of marketability for private company. Of course, most private stocks suffer greatly from lack of marketability. To estimate the degree of discount for limited marketability, analyze the relationship between the share prices of companies initially offered to the public in IPOs and the prices at which their shares traded within a short period of time immediately before their public offerings. John Emory conducted the first comprehensive study of this type and showed private companies that could go public suffer from a lack of liquidity. The range of marketability discounts in the Emory studies was from 3% to 94%, with the median being 48%.6 Appraisers also cite a number of other studies, such as the restricted stock studies and numerous tax court cases, that indicate that LOMDs of more than 25% are justifiable to apply against indicated private values.

In Bernard Mandelbaum v. Commissioner, Tax Court judge David Laro created significant discussion within the valuation community by raising key issues regarding marketability discounts and setting forth ten factors to be considered in determining an appropriate discount for lack of marketability.7 These are:

1. Private versus public sales of stock

2. Financial statement analysis

3. Company's dividend policy

4. Nature of the company, its history, position in the industry, and economic outlook

5. Strength of company management

6. Amount of control transferred

7. Restrictions on transferability of stock

8. Holding period required in the stock

9. Company's redemption policy

10. Costs associated with making a public offering

More recently, Paglia and Harjoto matched sales transactions from Pratt's Stats with publicly traded counterparts to determine discounts for lack of marketability (DLOMs).8 The estimated DLOMs based on matching criteria of net sales and EBITDA indicate that DLOMs for private firms average 68% for earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) matches and 72% for revenues pairings. They also found that Food, Professional Services, Support, Finance, Retail, Wholesale, and Information areas of the economy exhibit the highest discounts. Furthermore, they reported that firm size (assets and sales), profitability (net income and EBITDA) are negatively related to the size of the discount. Overall, their findings suggest there is justification for larger discounts when preparing a valuation engagement.

Key Person Discount

Often the key person discount is applied when a key person is no longer going to be part of the business. This is often the case when the valuation is of a decedent's estate. No key person discount table helps determine the size of this discount. Most appraisers forecast the financial results of the business without the key person, which should decrease the future income. Another way to handle this loss is to increase the riskiness of achieving the future income by increasing the discount rate.

Perhaps the most famous court case involving a key person discount is the Paul Mitchell decision, where the court assigned a 10% key person discount to indicate the loss of value to the company after Paul Mitchell died.9 Subsequent discussion on this case, especially by Larson and Wright, indicates the Paul Mitchell case is unique, partly in the fact that the key person's name coincided with the name of the firm.10 Larson and Wright note that over an eight-year period, declines in value due to a key person's death in public companies were in evidence less than half the time and were only in the 4% to 5% range when a decline was noted.11 It is generally not advisable to employ a key person discount of more than 10% to an appraisal's unadjusted indicated value. Unless no LOMD is taken, a large key person discount is difficult to justify.

Nonvoting Discounts

The concept of voting rights, or the lack thereof, attached to a minority interest ownership in a business is one of the most difficult variables to quantify. Theoretically, it is logical and supported by valuation theory and case law that if an ownership lacks the ability to elect directors and set the policy course of a business, any value attributable to control will be diminished accordingly, all other things being equal. This is the fundamental premise of a minority interest being worth less than a proportionate share of the business on a control basis.

First, if an additional class of shares are issued by a corporation, a dilution in ownership occurs, whether the shares are voting or nonvoting. Thus, the per-share claim of the stockholder on the earnings and assets of the business is diminished. Therefore, this dilution should result in a proportionate reduction in fair market value.

Next, the matter of voting rights is inseparable from the concept of control and should increase to the extent that these rights become meaningful. For extremely small minority interests, the market typically grants only a small amount of value to voting rights. But where swing votes or significant minority ownerships are involved, the impact can indeed be significant.

For example, if one were to hold only ten shares of a publicly traded corporation with 500 million shares outstanding, the impact of whether the ten shares are voting or not is insignificant. However, in the situation of a closely held business where a relatively small number of shares are outstanding, even small minority interests could combine to have an impact on voting issues whereas nonvoting shares would be prohibited from doing so regardless of the proportion of ownership.

Thus, nonvoting shares in a closely held business are inherently worth less than corresponding voting shares and should be subject to additional discount.

The quantification of a nonvoting discount arises from various studies of public securities markets and case law. A study by Kevin C. O’Shea and Robert M. Siwicki reviewed 43 publicly traded stocks with both voting and nonvoting shares of common stock outstanding.12 They found a wide range of premiums of voting stocks over nonvoting stocks, or from a discount of 8.6% to a premium of 32.8% with an average of 3.8%. The authors noted that the context in which the minority ownership is placed, or whether the voting minority interest is significant, rather than the absolute question of voting versus nonvoting, that appears to impact the question of value. Nevertheless, the implication is that nonvoting shares do have an inherent discount of at least about 4% from voting shares, on a minority interest basis, in this study.

Other discounts may be appropriately applied to various methods. Examples include but are not limited to discounts for:

- Key customer dependence

- Obsolescence of technology

- Blockage

- Built-in capital gains

- Key product dependence

These and other unnamed discounts are beyond the scope of this book; readers should seek further information if needed.13

Step 7: Derive a Final Value Conclusion

Appraisers take two steps to derive a final value conclusion. First, they apply premiums and discounts to each method as appropriate. Application is made as appropriate on a specific method basis, since each method may yield an initial result at a different value level. If all methods yield an unadjusted indicated value at the same value level, for example, marketable, minority interest, then premiums or discounts are applied once.

Second, after the application of adjustments (called the adjusted indicated value), appraisers decide how to synthesize the various values. The application of premiums and discounts is usually multiplicative, not additive. The next example shows this calculation, from unadjusted indicated value to adjusted indicated value.

| Unadjusted indicated value: | |

| Value on a control, marketable basis | $1,000,000 |

| Less minority discount (30%) | 300,000 |

| Value on a minority, marketable basis | $700,000 |

| Less LOMD (35%) | 245,000 |

| Adjusted indicated value | $455,000 |

The cumulative discount in this example is 54.5% (1 – ($455,000/ $1,000,000)).

Weighting and Final Value Conclusion

Reconciliation is one of the more difficult issues in a valuation. Normally, the appraisal yields several adjusted indicated values. The appraiser is not bound to include all of these values in the value conclusion. However, the appraiser discusses in the report the reasons for inclusions/exclusions of methods within the valuation. In this way, the reader at least knows the appraiser's reasoning.

Once the appraiser decides which values to include and has applied the necessary premiums and discounts to arrive at adjusted indicated values, the decision on how to weight the various adjusted indicated values is made. There are two primary ways to weight these values: explicit and implicit.

Explicit Weighting

In explicit weighting, the appraiser assigns percentage weights to each adjusted indicated value. An example of explicit weighting follows.

In this case, the appraiser decides to weight the private guideline method the heaviest, with much lighter weighting given to the capitalized earnings and net asset value methods. Although this example does not show it, the appraiser might choose to weigh 100% of the value opinion using one method. This could happen if a subject was highly profitable but no guideline companies are found. In this case, the appraiser might assign all weight to the capitalized earnings method. Although once again, the appraiser must explain in detail the rationale for why this weighting is chosen, the final weighting is based on subjective reasoning by him or her.

Implicit Weighting

Some appraisers use an implicit weighting scheme in the final reconciliation process. Adjusted indicated values from the various methods are presented and then a value conclusion is determined. Once again, the appraiser gives the reasons why one method's results are favored over another. Implicit weighting does not employ a quantitative presentation; rather, the appraiser chooses a final value and presents the reasoning. Here is an example of implicit weighting:

| Method | Adjusted Indicated Value per Share | |

| Capitalized earnings | $20.00 | |

| Net asset value | 15.00 | |

| Private guideline | 30.00 | |

| Value conclusion per share | $25.00 |

Ultimately the value conclusion is stated as a point estimate or a range of value. A point estimate is the typical result of a fair market valuation, whereas a value range is more typical for a market valuation.

KEY STEPS TO DERIVE FAIR MARKET VALUE

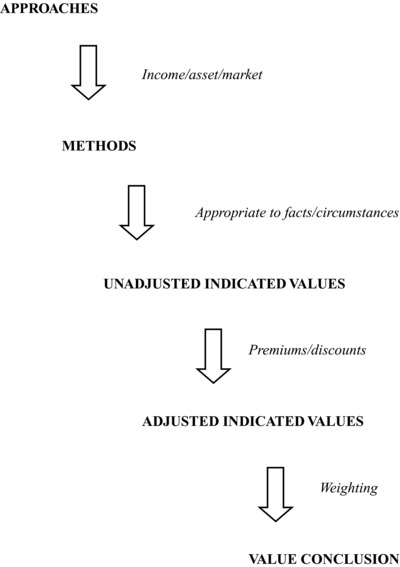

Exhibit 8.6 summarizes the key steps involved in deriving FMV. The three broad approaches utilize methods appropriate to the facts and circumstances of the appraisal. The methods yield unadjusted indicated values that may reside at the appropriate value level of the subject interest. If the unadjusted indicated values need adjusting, premiums or discounts are applied to create adjusted indicated values. Finally, the adjusted indicated values are weighted according to the judgment of the appraiser to determine the value conclusion.

Figure 8.6 Key Steps to Derive Fair Market Value

Business appraisers need to take special care when deriving fair market values. In 2010 the IRS issued a new IRC Section 6695A penalty, “Letter 4485, Appraiser Penalty Assessment Notification Letter.” These “new” regulations could impose a significant monetary penalty on an appraiser for “significantly” under- or overvaluing a subject company in regard to IRS regulations.

DOES THE FAIR MARKET VALUE PROCESS MAKE SENSE?

Many owners have difficulty understanding the fair market valuation process. This difficulty emanates from the incongruence between the goal of the process, which is to estimate a likely price of a business interest, and the value conclusion, which may bear no resemblance to what the market actually would pay. An obvious example of this incongruence is the appraisal of a private minority interest. Since there is no market for these interests, does it make sense to draw a value conclusion by comparing the private interest to a group of public securities using the market approach with a discount for lack of marketability and other factors? More than likely, the market value of the private minority interest is quite low, perhaps even zero. Yet the FMV of the interest may be quite high. Exhibit 8.7 depicts the problem with the market approach.

EXHIBIT 8.7 Appraisal Twister?

| P/E | |

| Public guidelines per share average (daily stock prices) | 15 |

| Less marketability discount (30%) | (4.5) |

| Less key person discount (10%) | (1.0) |

| Private company minority per share | 9.5 |

If a group of public guideline companies have an average price/earnings ratio of 15 and routine discounts are applied, a price/earnings ratio of 9.5 would be applied to the subject's minority interest–level earnings to derive a minority interest value. Many valuation analysts believe comparing private to public stocks consistently overvalues private minority interests. This process is somewhat like appraisal Twister because nonsensical rules of the game dominate actions of the participants and the ultimate outcome.

Another example of the disconnect between FMV and actual market reality can be found in the way that discount rates are derived. The buildup method (BUM) is a widely recognized method of determining the after-tax net cash flow discount rate, which in turn yields the capitalization rate. BUM is used primarily in the FMV world. It is called a “buildup” method because it is the sum of risks associated with various classes of assets. It is based on the principle that investors would require a greater return on classes of assets that are more risky. The BUM model is:

![]()

Ke = Required rate of return on equity

RF = Risk-free rate of return

ERP = Equity risk premium

SRP = Size risk premium

IRP = Industry risk premium

CSRP = Company-specific risk premium

The first element of the BUM model is the risk-free rate, which is the rate of return for long-term government bonds. Investors who buy large-cap equity stocks, which are inherently more risky than long-term government bonds, require a greater return, so the next element of the BUM is the equity risk premium. In determining a company's value, the long-horizon equity risk premium is used because the company's life is assumed to be infinite. The sum of the risk-free rate and the equity risk premium yields the long-term average market rate of return on large public company stocks.

Similarly, investors who invest in small-cap stocks, which are riskier than blue-chip stocks, require a greater return, called the “size premium.” Size premium data is generally available from two sources: Morningstar's (formerly Ibbotson & Associates’) Stocks, Bonds, Bills & Inflation and Duff & Phelps’ Risk Premium Report.

By adding the RF, ERP, and SRP, the rate of return that investors would require on their investments in small public company stocks can be determined. These three elements of the BUM discount rate are known collectively as the systematic risks.

In addition to systematic risks, the discount rate must include unsystematic risks, which fall into two categories. One of those categories is the industry risk premium. Morningstar's yearbooks contain empirical data to quantify the risks associated with various industries. The other category of unsystematic risk is referred to as company-specific risk. No published data is available to quantify specific company risks. Instead, they are determined by the valuation professional, based on the specific characteristics of the business and the professional's reasonable discretion applied to appropriate criteria.

By way of example, PrivateCo's Ke can be determined in this way:

![]()

PrivateCo's required rate of return on equity is 23%. Due to the nature of the variables used to derive BUM, this return on equity rate is stated on an after-tax basis. For the purposes of this chapter and book, we seek to determine a pretax capitalization rate. This will then be used to determine an enterprise fair market value, which will be comparable to the values derived for all other value worlds.

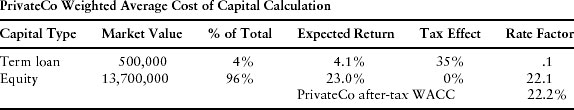

The next step in determining PrivateCo's capitalization rate is to derive its weighted average cost of capital (WACC), which is on an after-tax basis. The WACC tax-effects PrivateCo's debt to make it after tax, as shown:

Thus, PrivateCo's WACC is 22% (as rounded). Now we need to convert to a pretax capitalization rate. There are two steps in converting WACC to a pretax capitalization rate:

1. Convert the after-tax discount rate to an after-tax capitalization rate by subtracting the estimated growth rate. Assume PrivateCo's long-term growth rate is expected to be 5%. The after-tax discount rate of 22% converts to an after-tax capitalization rate of 17%.

2. Convert the after-tax capitalization rate to a pretax capitalization rate by dividing the after-tax capitalization rate by 1 minus the tax rate. Assume PrivateCo's tax rate is 35%. The after-tax capitalization rate, when rounded, converts to a 26% pretax capitalization rate (17% ÷ (1 – .35)).

For this example, PrivateCo's pretax capitalization rate is 26%.

TEARING DOWN THE BUILDUP MODELS

There are several issues regarding the BUM (or CAPM) model.14 Appraisers rely on the fungibility of capital argument to support the belief that investors can choose to substitute investments in public or private markets with equal ease. Thus, an investor in middle-market private equity could always achieve the risk-free rate by buying government securities. They use a BUM adding return to the risk-free rate to compensate for the additional risk of private market investing. There are several weaknesses with this argument.

The fungibility approach ignores market segmentation, investor return expectations, differences in access and cost of capital, and differences in how each market works as well as distinctly different behavior of players in each market segment who are guided by different market theories. This approach to valuation is misguided and introduces procedural and substantive errors that threaten to render appraisals irrelevant.

Appraisers use financial models—such as CAPM or the BUM—which are based on this fungibility theory. But these models are not designed to directly yield cost of capital for private companies; rather, they generate rates by reference to returns in another market, the public market. This is like drawing conclusions about a neighborhood pond by studying an ocean, then making “necessary” adjustments to describe the pond. Why not study the pond directly—or in the case of appraisal, why not use return expectations from the subject's market segment to derive cost of capital?

Appraisers rely on the fungibility of capital argument to support the belief that investors can choose to substitute investments in public or private markets with equal ease. Thus, an investor in middle-market private equity could always achieve the risk-free rate by buying government securities. They use a BUM, adding return to the risk-free rate to compensate for the additional risk of private market investing. There are several weaknesses with this argument, however.

The fungibility argument does not stipulate the necessity of adopting the risk-free rate as a standard. Why that standard rather than a variety of others? That money is fungible does not necessarily lead to the adoption of the risk-free rate as an objective standard, or even an adequate standard. The presence of elaborate retrograde calculations to make it fit the market indicates that it is not sufficient.

Once again, the logic of substitution governs this situation. Specifically, the relevant market of investors determines the cost of capital by defining and quantifying opportunity costs within a market. For example, private equity firms are frequently restricted by their charters and cost of funds from investments outside specific markets. They can never achieve the risk-free rate without abandoning the private equity market and investing in another market with fundamentally different risk and return expectations, information and liquidity functions, and value-creating models. Because there is no clear and necessary substitution, cost of capital is properly based on market costs, not book value, or firm value, or a standard appropriated from another market.

Players within a market do not approach the problem of calculating real-world investment decisions this way. Imagine private equity or mezzanine investors trying to decide whether they should invest in the private market or in a risk-free government instrument. They cannot do this because their capital is raised at lower cost and their mission is to reinvest it in a market with greater return expectations. That market necessarily has different risk and return characteristics.

The use of valuation models built on the fungibility argument uses functions and attributes of divergent markets, yielding fundamental contradictions. It conflates incompatible value worlds (standards of value) that operate with dissimilar rules and standards and are governed by diverse authorities, often with irreconcilable boundaries. Therefore, using the risk-free standard as a base is logically inadequate in that it purports to be an independent standard but is in fact systemically bound to a different, mismatched theoretical market. Capital may be fungible, but it is not fully substitutable. A scale derived from direct observation of the market is more accurate, useful, and responsible than a theoretical construct attempting to mimic that market.

TRIANGULATION

The language and lexicon of private business valuation started in the world of fair market value. Revenue Ruling 59-60 gave credence to a fairly structured appraisal process. Through the efforts of Shannon Pratt and others, fair market value represents the first concerted effort to apply the language and logic of economic theory to private business valuation.

| World | PrivateCo Value |

| Asset market value | $2.4 million |

| Collateral value | $2.5 million |

| Insurable value | $6.5 million |

| Fair market value | $6.8 million |

| Investment value | $7.5 million |

| Impaired goodwill | $13.0 million |

| Financial market value | $13.7 million |

| Owner value | $15.8 million |

| Synergy market value | $16.6 million |

| Public value | $18.2 million |

Unlike some of the other value worlds, FMV is a highly regulated value world. The main authorities in this world, the IRS and tax courts, have a high degree of influence tending toward control. Participants in this world must play by the authority's rules or be sanctioned. Regulated value worlds may exist in blind disregard to what really occurs in the marketplace. For instance, in the world of FMV, private minority business interests are presumed to have value, even if it means looking to the public capital markets to establish it. In the private capital markets, no such intrinsic value exists, unless an empowering agreement is in place between the shareholders. Even then the actual market for the minority interest may be limited to one or two other shareholders.

The regulated FMV world is linked to regulated transfer methods. ESOPs and various estate planning techniques, such as charitable trusts and family limited partnerships, are created and regulated by the government. All of the regulated transfer methods are valued in the world of FMV. This is an important insight. Government rules are present on both sides of the transaction. Likewise, FMV does not have standing with unregulated transfer methods, such as auctions and IPOs. Unregulated transfer methods are viewed through unregulated value worlds, such as market value and collateral value, which reflect values in a more dynamic setting.

An equally important consideration regarding triangulation is the lack of importance regarding FMV and the private capital markets. This market is driven by the actual exchange of debt and equity. Regulated value worlds are rarely employed in a market environment. This explains why FMV is rarely mentioned in a capital context.

NOTES

1. See Revenue Ruling 59-60, 1959-1 CB 237-IRC Sec. 2031.

2. PrivateCo Pretax Earnings on a Control Basis ($000)

3. Shannon P. Pratt, Robert F. Reilly, and Robert R. Schweihs, Valuing a Business: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held Companies, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill).

4. Christopher C. Mercer, Quantifying Marketability Discounts (Brockton, MA: Peabody Publishing, 1997), p. 19.

5. Mergerstat Review, 2007 (Santa Monica: Factset Mergerstat LLC, 2007), p. 24.

6. John D. Emory, “Expanded Study of the Value of Marketability as Illustrated in Initial Public Offerings of Common Stock,” Business Valuation News (December 2001), pp. 4–20.

7. T.C. Memo 1995-255, June 12, 1995.

8. John K. Paglia and Maretno Agus Harjoto, “Can Publicly Traded Company Multiples Shed Insights on Discounts for Lack of Marketability?” Business Valuation Review 29, no. 1 (July 2010): 18–22.

9. Estate of Paul Mitchell v. Commissioner, WL 21805-93, TC Memo. 1997-461, October 9, 1997.

10. James A. Larson, and Jeffrey P. Wright, “Key Person Discount in Small Firms: An Update,” Business Valuation Review (September 1998).

11. Ibid., p. 93.

12. Kevin C. O’Shea and Robert M. Siwicki, “Stock Price Premiums for Voting Rights Attributable to Minority Interests,” Business Valuation Review (December 1991).

13. Pratt, Reilly, and Schweihs, Valuing a Business, p. 430.

14. Rob Slee and John Paglia, “Private Cost of Capital Model,” Value Examiner (March 2010).