CHAPTER 13

Intangible Asset Value

Most value worlds are based on tangible assets and their benefit streams. In contrast, the world of intangible asset value is based entirely on assets that do not have a physical reality. Intangible assets comprise all the elements of a business enterprise that exist in addition to monetary and tangible assets. This world is based on human capital, information, technical know-how, customer relationships, branding, intellectual property (IP)—in short, the collective experience that adds value to a company. This emerging world has grown in influence because of the increasing relative importance of the factors it encompasses.

The concept of IP is not new in the United States. At the urging of Thomas Jefferson, language was adopted by the Constitutional Convention in 1787 designed “to promote the progress of science and the useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” This statement became part of Article 1 Section 8 in the U.S. Constitution. The history of economic progress is the story of combining intellectual creativity with the physical world to produce the economic necessities of life.

Today, it is not unusual to find an increasing chasm between the tangible asset value of a company and its overall enterprise value. Increasingly, intellectual assets are not adequately reflected on companies’ balance sheets. According to generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), purchased intellectual assets, along with all other acquired intangible assets, are recorded properly on balance sheets, but if those same assets are developed internally, they are not adequately noted. Assets with an identifiable benefit stream, such as patents, copyrights, logos, or trademarks, may be reflected on a balance sheet. Other intellectual capital (IC) with less objectively defined benefit streams, such as the knowledge and experience of a company's assembled workforce, are not reflected on the balance sheet. Knowledge assets generally are not reflected in financial statements and other forms of information available to decision makers.

A snapshot of the key tenets of the intangible asset world is provided in Exhibit 13.1.

EXHIBIT 13.1 Longitude and Latitude: Intangible Asset Value

| Definition | Nonphysical assets that grant rights, privileges, and have economic benefits for the owner. The intangible asset world breaks into two subworlds: intellectual property and intellectual capital. Intellectual property (IP) includes patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets. Intellectual capital (IC) equals the sum of human capital and structural capital. |

| Purpose of appraisal | To determine the intangible asset value of a company's IP or IC. |

| Function of appraisal | To derive the value of specific IP like a patent, for legal reasons, such as setting a royalty rate; or for market reasons, such as the possible sale of an intangible asset. IC appraisals tend to be oriented towards efficiency measures (i.e., to generate an indication of how well management is utilizing company assets). |

| Quadrant | IP: empirical regulated; IC: notional unregulated. |

| Authority | IP: federal government agencies such as the Patent Office plus certain laws, such as trademark laws.

IC: academics, consultants, and certain companies that have implemented IC methods. |

| Economic benefit stream | IP: the stream that emanates from the particular property.

IC: not stream oriented. |

| Private return expectation | IP: the expected return based on the riskiness of achieving the economic benefit stream.

IC: return expectations are unclear due to a weak identification of EBS. |

| Valuation process summary | IP: Depending on the type of IP (patent versus trade secret, etc.), the cost, income, and market approaches may be appropriate for use. The appraiser determines what approaches are suitable.

IC: Two main methods are employed. The scorecard method identifies various components of intellectual capital, which are scored and graphed. No estimate is made of the dollar value of the intangible assets. The direct intellectual capital method estimates the dollar value of intangible assets by directly identifying and valuing the various components. |

Unlike the situation in other business eras, intellectual value drives the benefit streams of most modern companies. Historically, companies could dominate industries by controlling access to natural resources and by managing manufacturing operations efficiently. Today, many heavy manufacturing concerns struggle to survive. In order to thrive, some manufacturing companies have turned to intellectual value or know-how. Many newer companies develop products and services not based on natural resources or a heavy balance sheet. These “service” companies have a heavier reliance on intellectual capital. Distribution businesses, software businesses, and consulting and training companies may develop significant value with relatively “light” balance sheets. Competitive advantage is increasingly based more on what is known than on what is owned. Companies today operate knowledge factories that convert raw knowledge into scalable and repeatable processes that create value for their customers.1

IC is of growing importance to companies today, but how can it be measured in a responsible and equitable fashion? What, for example, is the useful life of an intangible asset? Is there an intrinsic useful life? Certain intangibles, such as software, could be used indefinitely because they do not wear out. Yet often they become obsolete in 18 months or less. How can such intellectual assets be measured precisely?

In the world of impaired goodwill, the subject of Chapter 12, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) statements addressing some problems of adjusting and assessing goodwill were outlined. Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Topic 350 (formerly known as Statement No. 142) describes the accounting treatment of goodwill and other intangible assets. As opposed to amortizing goodwill over 40 years, this accounting principle does not allow for goodwill amortization. Instead, FASB requires an annual test for goodwill impairment. If goodwill carried on the balance sheet is worth more than its current “fair value,” the difference must be written off. The FASB intends to use this framework for future statements on intangible valuation issues. This framework relies on market comparisons to draw value conclusions.

There is international recognition of the growing importance of intellectual capital. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the International Accounting Standards (IAS) Committee are working on the central issue. They want to develop standards for recognizing expenditures as legitimate long-term investments in intangible value, which in turn creates assets. In order for a proper judgment to be made, an intangible asset must be clearly identifiable and separable from other assets of the company, such as goodwill. If these expenditures cannot be segregated properly on the balance sheet, they must be expensed as incurred. For example, research and development and brand development may be capitalized and depreciated on the balance sheet, or they may be expensed as incurred. It depends on how they are recognized. OECD and IAS have been working for a number of years on developing international standards for treating this complex issue.

The world of intangible asset value can be divided into two distinct areas. The first is the more traditional subworld of IP. The second, more recent and less well defined, is the emerging subworld of IC. The two areas differ from each other in a number of significant ways.

SUBWORLDS

The authority governing the world of IP is comprised of various government or quasi-governmental agencies, such as the U.S. Patent Office, plus certain laws, such as trademark laws. The authority in the subworld of IC is the academic and consulting industry as well as a few large firms.

For an intangible taking shape in the subworld of IC to cross the bridge into the subworld of IP, it must meet the rigorous standards prescribed in GAAP. Essentially, the intangible asset must be describable in language acceptable to the accounting authorities, and it must conform to the logic embedded in the system of accounting standards.

Terminology in the two subworlds may be similar, but it carries different meanings. For example, the term “intangible” obviously is used in both subworlds. However, intangible property is more substantial and recognizable in accordance with a strict set of standards, while the intellectual assets found in the subworld of IC have not passed the recognition tests required by the authorities.

The subworld of IP excludes by definition the intangible assets that populate the subworld of IC.

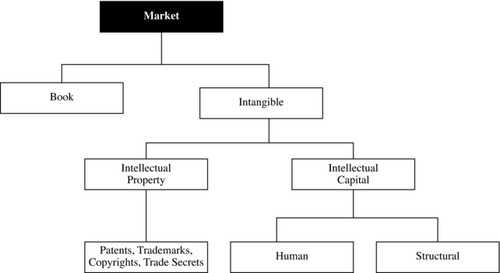

IC authorities strive to recognize the sources of value and improve productivity. There is an international effort to identify and describe the intangibles in this world so that they can be recognized in a replicable fashion and admitted into the subworld of IP. One of the weaknesses of the intangible property world is that no common language exists. As agreement on language develops, standards of practice become possible. Among the more interesting developments is Exhibit 13.2, adapted from a program started by the Skandia Company in the 1980s. It depicts the linkage between market value and the various types of capital.

EXHIBIT 13.2 Value Scheme

In this schematic, market value equals the sum of a company's book value plus intangible assets. Intangible assets then become all other value of the company that is not identified on a company's financial statements. More precisely, intangible assets are comprised of IP and IC. IP includes patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets, with the latter item sometimes called know-how or proprietary technology. The components of IP are described in detail later in this chapter.

IC equals the sum of human capital and structural capital.2 Bontis, a leading researcher in this field, defines human capital as “the combined knowledge, skill, innovativeness, and ability of the company's individual employees to meet the task at hand.” It also includes the company's values, culture, and philosophy. The company cannot own human capital. Structural capital is the hardware, software, databases, organizational structure, and everything else of organizational capability that supports those employees’ productivity.3 In other words, structural capital is what gets left behind when the employees go home at night. Structural capital enables customer capital, which are the relationships developed with key customers. Unlike human capital, the company owns structural capital.

Valuing intangible assets is a difficult task. Yet measuring intangibles is an important exercise since they are becoming a larger part of many companies’ value propositions. There are four categories for measuring intangibles on a general level.4 The first two apply to the valuation of intangible assets in general; the final two apply to the measure of IC.

Intangible Assets Categories: General

The next methods derive the value of intangible assets in general.

- Market capitalization methods (MCM). The difference between a company's market capitalization and its stockholders’ equity is calculated as the value of its IC or intangible assets.

- Return on assets (ROA) methods. The average pretax earnings of a company for a period of time are divided by the average tangible assets of the company. A company's ROA is then compared with its industry average. The difference is multiplied by the company's average tangible assets to calculate an average annual earnings from the intangibles. Dividing the above-average earnings by the company's average cost of capital or an interest rate, an estimate of the value of its intangible assets or IC is derived.

Intellectual Capital Categories

The next methods are used to value IC.

- Scorecard (SC) methods. The various components of intangible assets or IC are identified and indicators and indices are generated and reported in scorecards or as graphs. Scorecard methods are similar to direct IC methods, except that no estimate is made of the dollar value of the intangible assets. A composite index may or may not be produced.

- Direct intellectual capital (DIC) methods. The dollar value of intangible assets is estimated by identifying its various components. Once these components are identified, they can be directly evaluated, either individually or on a consolidated basis.

Within each category, a number of different methods exist. These methods enable the valuation of specific intangible assets. Exhibit 13.3 describes some of these methods with corresponding categories. There are advantages and disadvantages to methods offering dollar valuations, such as ROA and MCMs.5

EXHIBIT 13.3 Sample Intangible Asset/Intellectual Capital Valuation Methods

Advantages of ROA and MCM Methods

- They are useful in merger and acquisition situations and for stock market valuations.

- They can also be used for comparisons between companies in the same industry.

- They are good for illustrating the financial value of intangible assets, a feature that tends to get the attention of chief executive officers.

- Because they build on long-established accounting rules, they are easily communicated in the accounting profession.

Disadvantages of ROA and MCM Methods

- By translating everything into monetary terms, they can be superficial.

- ROA methods are very sensitive to interest rate assumptions.

- Methods that measure only on the organization level are of limited use for management purposes below the board level.

- Several methods are of no use for nonprofit organizations, internal departments, and public sector organizations. This is particularly true of the MCMs.

Advantages and disadvantages of the direct IC and SC methods are listed next.

Advantages of Direct IC and SC Methods

- They can create a more comprehensive picture of an organization's health than financial metrics.

- They can be applied easily at any level of an organization.

- They measure closer to an event, so reporting can be faster and more accurate than pure financial measures.

- Since they do not need to measure in financial terms, they are useful for nonprofit organizations, internal departments, and public sector organizations as well as for environmental and social purposes.

Disadvantages of Direct IC and SC Methods

- The indicators are contextual and must be customized for each organization and each purpose, which makes comparisons very difficult.

- The methods are new and not readily accepted by accounting authorities and managers who are accustomed to seeing everything from a pure financial perspective.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

The IP subworld is a more fully developed area of the world of intangible asset value. The term “intellectual property” refers to patents, trademarks, copyrights, and trade secrets6 protected by law from unauthorized use by others. Each type of IP is defined as presented next.

- Patents: A patent is the grant of a property right by the U.S. government to the inventor by action of the Patent and Trademark Office.7 The right conferred is a “negative right,” in that it excludes others from making, using, or selling the invention.8 There are numerous types of patents, with varying degrees of length of protection. Two of the major types are:

1. Utility patent. This patent type is covered under Section 101 of the United States Code, which states: “Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor.” Utility patents have a term of 20 years from the date of filing the application.

2. Design patent. “Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor.”9 Design patents are issued for 14 years and protect only the appearance of an object, not its structural features.

- Trademarks. A trademark “includes any word, name, symbol or device or any combination thereof adopted and used by a manufacturer or merchant to identify his goods and distinguish them from those manufactured by others.”10 Registration under the Trademark Law Revision Act of 1988 continues for ten years and may be renewed for additional ten-year periods as long as the trademark is in use.

- Copyright. A copyright protects the expression of an idea, not the idea itself. Examples of copyrighted materials are literary works, musical works, motion pictures, sound recordings, and pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. To be protected, the expression must be set to some tangible form. The copyright does not have to be registered with the Copyright Office to receive protection. Copyrights are protected for the life of the author plus 70 years.

- Trade secrets. There are a number of definitions for trade secrets, also called proprietary technology. One court decision defined trade secrets as “any information not generally known in the trade. It may be an unpatented invention, a formula, pattern, machine, process, customer list, or even news.”11 Trade secrets are governed by state laws, so the meaning and protection varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. Many trade secrets involve patentable inventions. The company may choose not to patent the secret in order to eliminate the need to educate the public regarding the secret. A trade secret does not have to be stated in tangible form to be protected.

Proprietary technology can take many forms. For proprietary technology to be classified as trade secrets, it must be used in the business, provide its owner with a competitive advantage, and be treated as a secret.12 A few examples are listed next.

- Decision logic in computer software

- Formulas, recipes, methods of combination

- Technical experience captured in drawings, tooling, process designs

- Research and development information, such as laboratory logs and experimental designs

- Customer relationships

- Business knowledge—supplier lead times, names, alternate suppliers, cost and pricing data

Approaches to Valuation

There are three primary approaches for valuing IP: the cost approach, the market approach, and the income approach. Each approach has underlying methods that can be used to perform the valuation. Each of these approaches is especially well suited to certain types of IP. For instance, the cost approach is well suited for valuing copyrights as opposed to patents, which might be valued using a method within the income approach.

The cost approach calculates what it would cost another business to duplicate a given asset. More precisely, this approach seeks to measure the future benefits of ownership by quantifying the amount of money required to replace the future service capability of the subject property. Assets that can be valued using the cost approach include:

- Internal software

- Assembled workforce

- Customer relationships

- Corporate practices and procedures

- Distribution networks

For example, suppose PrivateCo owns a sophisticated, proprietary cost-estimating software system that took many years to create and is now central to the success of its business. No comparable off-the-shelf system is available for purchase. By using the cost approach, it is possible to measure what another company might need to spend to duplicate that cost-estimating package. In this way, PrivateCo would be able to establish a value for its own proprietary system.

The income approach measures, in today's dollars, the future benefits IP will bring to the holder. There are several methods underlying this approach: multi-period excess earnings method, relief-from-royalty method, differential value method, profit split method, yield capitalization method, and direct capitalization method. The capitalization or discount rate used in this analysis should mirror the risk of achieving the income that is being capitalized or discounted. Assets that can be valued using this method are:

- Commercial software

- Brand names

- Copyrights

- Trademarks

- Patents

- Technology

- Favorable contracts

- Customer relationships

- Licenses and royalty agreements

- Employment agreements

Sometimes the income methods incorporate savings to the holder as part of, or in replacement for, the income stream. This savings feature occurs when a particular patent enables the holder not to pay a royalty. In such cases, the relief-from-royalty method is applied. For example, assume a company holds a patent that it is not currently using in its business. Another company might be able to use this patent in its core business, enabling it to discontinue the payment of a royalty to an outside holder. In this case, if the current royalty stream is $300,000 per year and the capitalization rate is 20%, the patent might be valued at $6 million.

The market approach is the most direct approach to value IP. This approach uses the measure of what others have paid for a comparable asset in an active public market. The sale of IP in the marketplace is completed most frequently as part of the sale of a company. While some of the purchase price may be allocated to intangible assets, it may not be directly applied to a particular IP asset. Occasionally IP is traded independently from the enterprise. Several examples are:

- Sale of Gloria Vanderbilt trademark by Murjani in 1988 for $15 million to Gitano

- Sale of the Hawaiian Punch brand from Procter & Gamble to Cadbury Schweppes PLC for a reported $203 million early in 1999

- Sale of the After Six trademark as part of bankruptcy liquidation for $7 million in 1993.

- Purchase of the Pet Smart logo for $10 million in 2002

As is the case with the guideline method, comparability is difficult to establish when comparing IP. Databases contain hundreds of IP sales. Using similar techniques to those found in the guideline method for determining enterprise value, it is possible to derive IP value using the market approach. The next assets can be valued using the market approach:

- Trademarks

- Impaired goodwill

- Patents

- Logos

- Brands

The next example illustrates a trade secret valuation.

EXAMPLE

PrivateCo has the opportunity to acquire a trade secret from CompetitorCo, which is converting one of its manufacturing lines to product lines not competitive with PrivateCo. The trade secret is the ability to run a production line at nearly twice the rate as PrivateCo, which runs a nearly identical line. Joe Mainstreet realizes the increased production capability will enhance PrivateCo's profits but is uncertain how to value such an opportunity. No tangible assets would be purchased since CompetitorCo keeps the equipment.

PrivateCo estimates it can save $3 million per year in manufacturing costs by implementing the trade secret. The market for PrivateCo's widgets is expected to decrease 20% per year for the next five years. Mainstreet believes PrivateCo's cost of capital for all new investments is 25%. How much can PrivateCo afford to pay for this secret?

If Joe Mainstreet is like every other red-blooded capitalist in America, he would try to figure out how to speed up his line without paying CompetitorCo. If this engineering attempt fails, he might consider making an offer for the trade secret.

PrivateCo receives the listed incremental savings from the acquisition:

| Year | Savings | Present Value (25%) |

| 1 | $3,000,000 | $2,400,000 |

| 2 | $2,400,000 | $1,500,000 |

| 3 | $1,800,000 | $900,000 |

| 4 | $1,200,000 | $500,000 |

| 5 | $600,000 | $200,000 |

| Total | $5,500,000 (as rounded) |

PrivateCo could pay CompetitorCo $5.5 million for the trade secret and receive a 25% compounded return on its investment. In real life, Joe Mainstreet would offer $250,000 and be genuinely offended when CompetitorCo countered at $500,000.

INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL

The SC and direct IC categories of IC valuation are mentioned previously. The Skandia Navigator method is described in the SC methods category. Skandia is a pioneering company in the creation and use of IC measurement techniques. The Skandia report uses up to 91 new IC metrics plus 73 traditional metrics to measure the five areas of focus making up the Navigator model. Exhibit 13.4 summarizes some of these metrics.13

EXHIBIT 13.4 Sample of Skandia IC Measures

| Financial focus |

|

| Customer focus |

|

| Process focus |

|

| Renewal and development focus |

|

| Human focus |

|

Scandia's Navigator uses 112 indices that offer direct counts, dollar amounts, percentages, and survey results. Navigator's five focus areas have 36 monetary measures that cross-reference each other. Skandia assigns no dollar value to its IC but uses proxy measures of IC to track trends in the assumed value.14 The Navigator method is more of a management tool for assessing the effect of IC on the company, as opposed to a direct measurement technique. Because SC methods incorporate so many variables, they tend to be directionally accurate as measures of the overall value of IC.

The direct IC methods suffer from many of the problems associated with the SC methods. Most notably, the conversion from qualitative measures to quantitative values is difficult at best. One such method, Technology Broker created by Brooking, defines IC as the combined value of four components: market assets, human-centered assets, IP assets, and infrastructure assets. The value of these components is derived mainly from the organization answering a series of questions, such as:

- In my company, every employee knows his job and how it contributes to corporate goals.

- In my company, we evaluate return on investment on research and development.

- In my company, we know the value of our brands.

- In my company, there is a mechanism to capture employees’ recommendations to improve any aspect of the business.

- In my company, we understand the innovation process and encourage all employees to participate within it.

This method then asks a series of specific audit questions to determine the amount of contribution relative to each of the four asset categories. In total, the Technology Broker IC Audit comprises 178 questions. Once again, many of these questions are qualitative in nature, such as: “To what extent are the patents owned by your company optimally exploited?” Once an organization completes its Technology Broker IC Audit, Brooking offers the cost, market, and income approaches to calculate a dollar value for the IC identified by the audit. Technology Broker's strength is to cause an organization to delve deeply into its intellectual underpinnings. Its weakness is that the conversion into quantitative values is not a direct line.

TRIANGULATION

The world of intangible asset value is an emerging world that will continue to increase in importance in the coming years. Global business models increasingly rely on intangible assets to meet goals and generate value. Managing and measuring these assets is a challenge for every business.

This world has two subworlds, intellectual property and intellectual capital. IP is the more familiar subworld, as it is comprised of well-known terms, such as patents, trademarks, and copyrights. The IP subworld lies in the empirical regulated quadrant. Since its elements are observable and traded in a market, it is empirical. For instance, numerous Web sites on the Internet routinely transfer patents. The authority's legitimacy in this subworld is grounded in government action. This subworld is highly regulated by various governmental agencies.

The IC subworld is more intangible than IP. This subworld lies in the notional unregulated quadrant. It is notional because it cannot be observed in a market; it exists only as a construct. Proponents of IC struggle to apply a coherent analysis that will be accepted and employed by the business community. IC is also highly unregulated. Companies cannot borrow against their IC. They may access equity investment due to the strength of their human capital.

This subworld is not directly tied to market value. It is uncertain whether increases in IC lead to increases in market value, especially for private companies. Similar to the creation of incremental business value, companies are probably better off by creating IC, but further study is required to understand how these benefits can be measured externally.

NOTES

1. Mary Adams and Michael Oleksak, Intangible Capital (Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2010), p. xiii.

2. Nick Bontis, “Assessing Knowledge Assets: A Review of the Models to Measure Intellectual Capital,” International Journal of Management Reviews 3, no. 1 (March 2001): 45.

3. Ibid.

4. Karl-Erik Sveiby, “Measuring Models for Intangible Assets and Intellectual Capital,” Unpublished paper, October 2002, p. 1; available at: www.sveiby.com.

5. Ibid., p. 2.

6. Gordon V. Smith and Russell L. Parr, Valuation of Intellectual Property and Intangible Assets, 3rd ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2000), p. 27.

7. Ibid., p. 35.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid., p. 36.

10. Ibid., p. 44.

11. Ibid., p. 28.

12. Ibid., p. 30.

13. Bontis, “Assessing Knowledge Assets,” p. 46.

14. Ibid.