CHAPTER 4

Market Value

The world of market value describes the value of a business interest in the marketplace. Value is normally expressed as an equity enterprise value. The owner who says his business is worth $X is generally referring to the world of market value. By seeking a market value for his business, an owner is motivated to find the open market value, probably envisioning a transfer.

“Market value” is defined as:

The highest purchase price available in the marketplace for selected assets or stock of the company.

This definition assumes the assets or stock of the company are valued on a debt-free basis, which means all interest-bearing debt must be deducted from the derived market equity values. Most market valuations are also done on a cash-free basis, meaning the seller keeps the excess operating cash and marketable securities in the company at the closing.

An owner whose motive is to derive the highest value obtainable in the marketplace focuses the appraisal process on the world of market value. Adapting a concept from commercial real estate appraisal, the market value focuses on determining the highest and best value for a business. No other value world has this goal or requires the combination of methods unique to this value world.

Rather than Internal Revenue Service (IRS) regulations, court precedents, or insurance company rules, financial intermediaries govern the market value. As with most private business valuation, market value requires a point-in-time expression of value. Determining value in this world requires a fair amount of market knowledge. In other words, the valuer needs to know what is really going on when two parties come together to make a deal.

Unlike the fair market value world, which employs the “willing buyer and seller” rule, the world of market value relies on the “unwilling buyer and seller” rule. Typically, these deals are struck in the real world when both parties are equally miserable with the resulting purchase price. Neither party is particularly willing to receive or pay what the other side is offering. Yet neither party is sufficiently unhappy to walk away from the deal. This tension allows deal makers to determine when the best possible deal is struck. This is the point of highest and best value because the buyer's company has the most identifiable synergies with the target company. The attraction is the strongest of all possible suitors, but if the terms were pushed any higher, the buyer would walk away from the deal.

Because financial intermediaries are the authority in market value, the language and concepts used in this world are those of the marketplace rather than legal or tax nomenclature. The parties take concepts such as synergy, cost reduction, market share, and leverage into consideration, but they are all in industry-specific language. No other theory of value fully attempts to account for these market considerations. Yet this is the world most interesting to owners. Many concepts in this world are simply not applicable in other value worlds. Moreover, many of these concepts are specifically restricted in other value worlds by the authorities and conventions of those value worlds. It is impossible to capture the world of market value using the lexicon and processes of other worlds.

While some of the processes of other value worlds are adapted here, there are distinct differences when they are used in the market value. Some processes have a general applicability across value worlds, with appropriate modifications. Yet they may have specific variations or interpretations within a given value world, and they may be combined with other conceptual approaches to yield quite different results.

For example, in fair market value, the subject of Chapter 8, there is a concept of market approach, which is one of the three main approaches used to determine fair market value. The market approach was originally linked to real estate appraisal, where information is used from transaction data of comparable properties to derive a value conclusion. Similarly in business appraisal, experts use transactional data from comparable or guideline business sales. These guideline transactions provide direction in determining applicable valuation parameters, or ratios. Then these are applied to the subject's performance and financial statements. For instance, typical ratios may include applying the guideline price/earnings or price/sales ratio to the subject company. Guidelines from public company data, which is voluminous and readily available, are frequently used despite difficulties in using public securities data to derive private value conclusions. Ultimately public data is not a relevant guide to valuing middle-market private stocks, especially in the world of market value.

Transactional data from private business sales is also used in the market approach. This is understandable since this type of data should be more relevant, and therefore more comparable, than the public data. With the advent of a number of private transactional databases, this data is also more available than ever before. There is definitely a place for private transactional data in determining the market value of private middle-market companies because these companies share a number of similarities. The use of transactional data is discussed in Chapter 2.

The goal of market approach in fair market value is to derive a hypothetical, defensible value in the middle of the road in terms of an indicated purchase price. In other words, the market approach generates a value the universe of potential buyers would be willing to pay for the subject company. In contrast, the world of market value generates the highest value the suitor with the greatest attraction would be willing to pay. Exhibit compares the two worlds.

EXHIBIT 4.1 Comparison of Two Value Worlds

| The World of Fair Market Value (market approach) | The World of Market Value |

| Notional (hypothetical) world | Actual world |

| Regulated by IRS/courts | Regulated by the market |

| “Willing buyer and seller … rule” | “Unwilling buyer and seller … rule” |

| World without special motivations | World characterized by special motivations |

| World without synergy | World with synergy |

Potential deal synergies or special motivations by the parties are not considered in the fair market value world. This stands in direct contrast to the goal of market value, which is to derive the highest possible value obtainable in the market. Potential synergies are valued in the world of market value. A deal in the private sector requires special motivations. More than likely, only one or two prospective buyers are willing to pay the market value of the subject. Theoretical assertions about the parameters of market synergies often shape highest and best value conclusions.

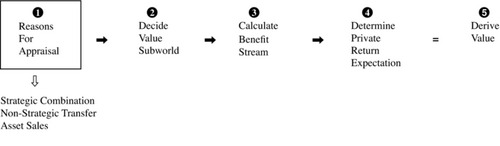

Exhibit 4.2 shows the process to determine market value.

EXHIBIT 4.2 Market Value Process: Select Appraisal Reason

EXHIBIT 4.3 Market Value Process: Decide Subworld

![]() Reasons for Appraisal

Reasons for Appraisal

In step 1, market value encompasses the transfer of assets or stock in a market setting. Market valuations may be required for strategic combinations or nonstrategic transfers. Unless otherwise stated, the valuation techniques described in this chapter do not apply to real estate or companies dominated by real estate. Real estate appraisal is a separate universe form business valuation. If the reason calls for a valuation in market value, the next step, shown in Exhibit 4.2, is to decide what value subworld is appropriate to use.

![]() Decide Value Subworld

Decide Value Subworld

Every company has at least three market values at the same time. This is yet another example of why market value, like all business valuation, is a range concept. Each market value step, called a subworld, represents the most likely selling price based on the most likely buyer type. The subworlds are asset, financial, and synergy. In the asset subworld, the most likely buyer is not basing the purchase on the company's earnings stream but rather on its assets. Therefore, the most likely selling price is based on net asset value. In this subworld, the buyer gives no credit to the seller for goodwill beyond the possible write-up of the assets. No value is given for goodwill or the ongoing operations of the company. Goodwill is the intangible asset arising as a result of name, reputation, customer patronage, and similar factors that result in some economic benefit a buyer is willing to pay beyond the subject's asset value.

The financial subworld reflects what an individual or nonstrategic buyer would pay for the business. With either buyer, the valuation is based only on the company's financial statements. The synergy subworld is the market value of the company when synergies from a possible acquisition are considered. Synergy is the increase in performance of the combined firm over what the two firms are already expected or required to accomplish as independent companies.1

Exhibit describes the subworlds.

EXHIBIT 4.4 Description of the Subworlds

| Subworld | Buyer Profile | Comments |

| Synergy | Strategic/synergistic | Synergies can result from a variety of acquisition scenarios. Perhaps the most quantifiable group of synergies comes from horizontal integrations. A horizontal integrator can realize substantial synergies by cutting duplicate overhead and other expenses. Some of these savings may be shared with the seller. Vertical integrations also can create substantial synergies. These tend to be strategic; the target helps the acquirer achieve some business goal. Synergies also can result from the different financial structures of the parties. For instance, the target may realize interest expense savings due to adopting the cheaper borrowing costs of the acquirer. |

| Financial | Individual/nonstrategic | Most individual buyers are financial buyers. Any institutional buyer who is not participating in the subject's industry or cannot leverage the subject's business is also a financial buyer. Financial buyers do not bring synergies to a deal; therefore, goodwill is limited. |

| Asset | Value investor | When the subject has no current or future earnings prospects, or it is in an industry that does not give credit for operating goodwill, its asset value may be the highest value it can achieve or expect. Companies in the same industry may buy and deploy the asset base without pricing in goodwill. |

The next two steps in the process for deriving market value, “Calculate the benefit stream” and “Determine the private return expectation,” require some explanation. The benefit stream (stream) is the benefit stream that is pertinent to the value world in question. The Stream is economic in that it is either derived by recasting financial statements or determined on a pro forma basis. Streams may be comprised of earnings, cash flow, and/or distributions. To derive values in the financial or synergy subworlds, the benefit stream is either capitalized or discounted by the private return expectation.

Private return expectation (PRE) is the expected rate of return that investors in the private capital markets require in order to fund a particular investment. The PRE converts a benefit stream to a present value. Thus the PRE can be stated as a discount rate, capitalization rate, acquisition multiple, or any other metric that converts the benefit stream to a present value. This annual return may involve the return to a specific investor or prospective group of investors.

The PRE is similar to the cost of capital concept, except that PRE's derivation changes based on the investor profile. For instance, the PRE for only one company can be determined by analyzing a company's weighted average cost of capital, as shown in Chapter 6. If the investor profile involves a prospective group of industry buyers, the PRE is calculated using industry selling multiples. Finally, if no industry multiples can be found, general investor returns are used to calculate the PRE.

Exhibit 4.5 illustrates the process to derive market value. By definition, the asset subworld does not use a benefit stream as part of the process to derive value. Benefit streams and PREs are discussed at length in Chapter 6.

EXHIBIT 4.5 Market Value Process: Derive Value

LEVELS OF PRIVATE OWNERSHIP

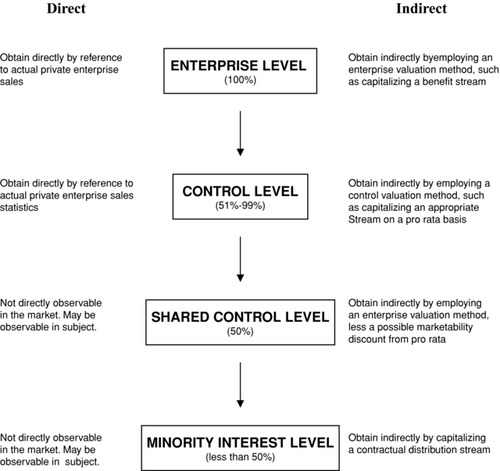

Chapter 2 introduced the concept that private business values are relative to the reason for their appraisal and that appraisal reasons can be grouped into value worlds. Within each value world, there are levels of valuation that correspond to ownership groupings. Exhibit 4.6 shows the levels of private ownership that correspond to the market value world. These ownership levels apply to most value worlds, except for fair market value, which employs a separate “Levels of Value” framework, discussed in Chapter 8.

EXHIBIT 4.6 Levels of Private Ownership

The enterprise level corresponds to 100% ownership. The next level is the control level, which is 51% or greater ownership. The third level is 50%, or shared control ownership. Finally, an ownership interest less than 50% is a minority interest.

Ownership levels are valued directly or indirectly. Direct observation means the level is determined by direct reference to actual comparable data. An example of direct observation at the enterprise level is the use of actual private enterprise transactions, probably generated from a private transactional database. An indirect observation relies on a method that indirectly estimates the value. For instance, capitalizing the company's earnings, which is an indirect reference to what the market should be willing to pay for the subject's earnings stream, may derive an enterprise value.

Once a value world is chosen, a benefit stream is identified or estimated. Then the process of defining value begins. Value levels represent the level within a value world by which to value specific business interests. Each level determines how value is derived. For instance, a minority interest level valuation within market value is appraised differently than an enterprise valuation, and so on.

Enterprise Level (100%)

The enterprise level of market valuation denotes 100% of a company's value. Since enterprise information about private company transactions in the private markets exists, enterprise values are the easiest private values to derive. Enterprise values are determined both directly and indirectly.

Enterprise Level: Direct

Enterprise values are obtained directly by reference to actual private enterprise sales. A number of databases contain information on enterprise sales. Chapter 6 focuses on the techniques used to derive values from private transactional information. Salient statistics from the main databases are presented next.

- Institute of Business Appraisers Market Database. The Institute of Business Appraisers maintains a database of information on actual sales of private businesses. The database has more than 30,000 records of enterprise transactions in over 650 Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) codes and is used mainly for smaller valuations (i.e., those less than $2 million). There are 13 points of information per transaction.

- Bizcomps. This database is published in two geographical editions: Eastern and Western. Each edition has about 5,000 transactions, with approximately 20 points of information per transaction. Bizcomps is used mainly for smaller valuations (those less than $5 million).

- Done Deals. Done Deals was started in 1996 and collects data from Securities and Exchange Commission filings. The database includes both public and private companies acquired by public companies. Approximately half of the deals are under $15 million and half over $15 million, and over 75% of the selling companies are privately owned. This database has over 9,000 transactions.

- Pratt's Stats®. Information is collected from a variety of deal-making sources. Most of the transactions reported in Pratt's Stats occur mainly in the $1 million to $30 million range. This database has the most detail per transaction, with approximately 88 data points.

- GF Data. GF Data's searchable database contains detailed information on business transactions ranging in size from $10 million to $250 million. This data is derived exclusively from more than 150 private equity groups, which ensures more reporting consistency than the other databases.

Other databases are used to supplement these sources, namely the Pepperdine Private Capital Markets reports.

Enterprise Level: Indirect

Enterprise values also are derived indirectly using methods that mirror what the market should be willing to pay for the business. There are a number of indirect valuation methods. Capitalizing the benefit stream of the enterprise is a frequently used method. Another example is net asset value method, which attempts to estimate market values of the company's assets and liabilities.

Indirect valuation is used when no direct valuation evidence is available or to complement direct findings.

Control Level (51%–99%)

In this book, a 51% to 99% ownership interest is considered a control value. Most states in the United States grant the rights of control in a private company at a minimum 51% interest level. Exhibit lists powers that an owner with control can exercise.2

EXHIBIT 4.7 Control Powers and Rights

|

1. Appoint or change operational management. 2. Appoint or change members of the board of directors. 3. Determine management compensation and perquisites. 4. Set operational and strategic policy of the business. 5. Acquire, lease, or liquidate business assets. 6. Select suppliers and vendors with whom to do business. 7. Negotiate and consummate mergers and acquisitions. 8. Liquidate, dissolve, sell out, or recapitalize the company. 9. Register the company's equity or debt securities for an initial public offering. 10. Declare and pay cash and/or stock dividends. 11. Change the articles of incorporation or bylaws. 12. Set one's own compensation, perquisites, and the compensation of related-party employees. 13. Decide what products and/or services to offer and how to price them. 14. Decide all matters relative to markets served. 15. Block any or all of the above actions. |

A controlling owner enjoys substantial benefits as compared to minority owners. Control transactions do not occur as often as enterprise deals. For this reason, it is more difficult to derive direct control valuations.

Control Level: Direct

Minority interest transactions typically are not reported to the private transactional databases mentioned earlier. Control transactions mainly occur as enterprise sales. Direct control valuation is a separate level because the 51%/49% partnership occurs quite often in the marketplace. Often the 49% owner does not realize the power and valuation difference between control and minority position when the entity is formed. Further, the articles of incorporation of the company usually do not grant the 49% holder any special rights. To protect their position, minority holders should structure an ownership agreement at the time of entity formation. Example tenets in ownership agreements include distribution rights, protections from orphan sales (the 51% holder cannot sell just the 51% interest without including the 49% holder), the ability to block major board of director decisions, and so on. Ownership agreements are described later in this chapter in the section titled “Ownership Agreement Tenets.”

For those situations where the minority has no special ownership agreement, the control value tends toward the enterprise value. Under this scenario, the control holder solely benefits from the power of controlling the finances of the firm. If the minority enjoys empowered rights, some part of the enterprise value is allocated to the minority, as discussed in the sectioned titled “Minority Interest Level.”

Control Level: Indirect

Since private databases do not contain control value transactions, most control values are determined indirectly. A number of methods involve indirect valuation. One example is to capitalize a benefit stream applicable to the control value.

As with the enterprise level, indirect valuation is used when no direct valuation evidence is available or to complement direct findings.

Shared Control Level (50%)

Shared control occurs when no single holder owns more than 50% of the enterprise. This occurs at many private companies, when two partners each own 50% of the stock. Unless the parties execute well-thought-out ownership and operating agreements before going into business, shared control is a difficult way to operate. Often the partners are in such a hurry to get into business for the least money possible that no working relationship documents are created.

Consider the next examples of what can go wrong with a 50/50 ownership structure.

- A company with 50/50 owners was in a rapidly changing market. This necessitated growing to another level to remain competitive. One 50% shareholder was prepared for this, the other was not. As a result, the company did not meet market need, eventually lost its top two customers and ultimately liquidated.

- One 50% shareholder at retirement age wanted to fund his retirement plan through the sale of his stock. His much younger partner was not in a position to purchase the stock. There were no buyers for 50% of the company. The older partner continued working many years past his wishes.

- A small company with equal shareholders grew into a highly successful medium-size firm. One partner believed he was primarily responsible for the firm's success and should be compensated more than his partner. The other partner did not agree, leading to total fallout between the two. There was no process to resolve the situation, and the company suffered as a result.

Consider the commonalties in these scenarios. First, the partners did no up-front planning, which might have prevented problems. Second, disagreements between partners are exacerbated as a company becomes successful. Often the early lean years glue the partners together, but the many options success brings unglues them.

What can be done to prevent gridlock between equal owners? At the time of entity organization, the parties should create ownership agreements. These legal agreements, such as a buy/sell agreement, shareholder and operating agreements, contain the key provisions on how the parties operate the business and treat each other. These agreements are necessary for any entity with multiple owners but are especially important for 50/50 or minority interest position holders.

Ownership Agreement Tenets

Ownership agreements are usually outlined by the partners and drafted with help from advisors. Every agreement is different and must be tailored to the circumstances. Chapter 28 details the major tenets of these agreements, but a few ideas are highlighted here.

- Duties and compensation are described.

- The process for adding more partners is detailed.

- What happens when a partner dies or gets disabled? How are the shares valued?

- What happens if a partner is terminated? How are these shares valued?

- Within the buy/sell agreement, is there a buyout provision to help break a deadlock?

- Who is on the board? Is there a tiebreak director?

There are dozens of issues for partners to consider. Seasoned corporate lawyers can help formulate well-rounded ownership agreements. The foregoing tenets are not exhaustive; actual agreements may be 20 pages long with annual amendments adding to their length. Of course, an ownership agreement can be put into place at any point in a company's existence. Every company with 50/50 owners should implement an ownership agreement before issues arise. When the agreement is needed, it is too late to draft it objectively.

Shared Control Level: Direct

No market exists for trading 50% private stock interests. The only direct evidence for valuing shared control situations rests in the ownership agreement, if one exists. Even if an ownership agreement with a valuation provision exists, there may be a marketability discount from the determined value. This discount from a fair offer is often described in a buy/sell provision and calls for a marketability discount, reflecting the fact that the 50% interest is marketable to only one party.

Shared Control Level: Indirect

Valuing a shared control interest indirectly usually means deriving an enterprise value, either directly or indirectly, then figuring a pro rata interest. In other words, enterprise value is divided by two. There may or may not be a need to discount the interest further due to the limited selling market, depending on the ownership agreement in place.

Minority Interest Level (Less than 50%)

A minority interest represents less than 50% of the stock of the company. This is the lowest value level, and these interests cannot be readily sold, so they generally suffer from a serious lack of marketability. Exhibit lists some issues minority holders should protect against when drafting ownership agreements with the majority holders.

EXHIBIT 4.8 Minority Interest Holder Protections

| Protect Against: |

|

| Lessen Vulnerability By: |

|

Even with the protections just identified, the minority holder still suffers from a lack of control, especially as it relates to financial policy.

Minority Interest Level: Direct

No marketplace exists for exchanging private minority business interests. Direct comparison to other private minority interests is limited to similar transactions in the company. Generally a prior transaction must have occurred in the past two to three years to make it usable as a guideline. Even recent prior transactions may not be a good value guide if the original buyer has no interest in acquiring additional shares. If an agreement describes a process for the majority to purchase the minority shares, this would be the best valuation method.

Minority Interest Level: Indirect

Without an ownership agreement within the subject company giving the minority holder special empowering rights, most minority interests in private companies are nearly worthless. One exception to this premise is a minority holder in an enterprise where the control shareholders have a targeted exit date, such as a firm owned by a private equity group. For the most part, however, unless the minority interest has a legal claim on dividends, liquidations, or other contractual distributions, the minority position has value only to the extent it participates in an enterprise sale. Few buyers outside the company assign weight to this future event.

If the minority interest holder has a contractual distribution stream, it is possible to value the position. The expected stream is capitalized at an appropriate risk factor. Even with a contractual distribution stream, few outside buyers have an interest in acquiring a minority interest in a private company.

TRIANGULATION

“Triangulation” refers to using two sides of the middle-market finance theory triangle to help fully understand a point on the third side. Equity value is affected by the company's access to capital and the transfer methods available to the owner. Capital availability influences market value. For example, industries that cannot attract capital tend to suffer from depressed market values and vice versa.

Private return expectations drive the market value of a firm, evidenced by selling multiples of comparable private transactions. Market values represent the most direct value linkage from the transfer side of the triangle. The synergy subworld of market value is the highest market value because of the transfer influence. The “market” determines the unique market valuation process. Financial intermediaries and asset appraisers are the authorities in this world. They enforce the process and provide feedback to the market. For instance, intermediaries use transfer experience to determine that, unless an empowering agreement exists, private minority interests are nearly worthless in the open market.

NOTES

1. Mark Sirower, The Synergy Trap (New York: Free Press, 1997), p. 20.

2. Jay E. Fishman, Shannon P. Pratt, J. Clifford Griffith, and D. Keith Wilson, Guide to Business Valuations, 9th ed. (Fort Worth, TX: Practitioners Publishing, 1999), chap. 7.