Variables

Variables are intrinsic to almost every program written. A variable is just that: “variable.” This means that the value of a variable can change. For example, say you were running a program that uses a high score that is stored in a variable. When the high score changes, the high score variable changes to reflect the new score.

Declaring Variables

Variables are very easy to use because they can be used as regular numbers. However, unlike numbers, variables must first be declared. When a variable is declared, the program knows that the variable exists, and you can use it in your program.

There are three types of variables in BASIC: integer variables, floating-point variables, and string variables. See Table 2.2 for a description of the types of variables.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| integer% | Fixed-point variables with no decimal places. |

| float# | Floating-point variables with decimal places allowed. |

| string$ | A text string. |

Note

When variables are created, they are automatically assumed to be integers, or whole numbers in other words. Therefore, the percent sign on all integer variables is unnecessary and from now on, they will mostly be omitted from the code.

Each type of variable is defined in a similar way. Simply type the name of the variable you want to define followed by the type symbol (%, #, or $). For example,

highscore% = 100 pi# = 3.14159 myname$ = "Maneesh Sethi"

Using Variables

You are now ready to write a few programs using variables. These programs should demonstrate a few important points about variables.

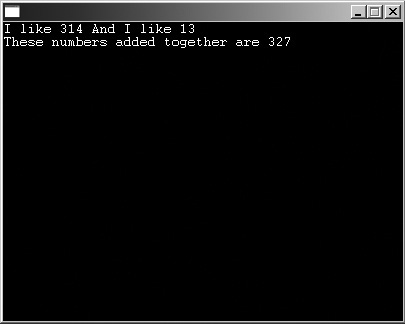

;demo02-02.bb - Adds two cool numbers ;VARIABLES favnum = 314 coolnum = 13 ;Print the two variables Print "I like " + favnum + " And I like " + coolnum ;Print the variables added together Print "These numbers added together are " + (favnum + coolnum) ;Delay for 5 seconds Delay 5000

The output is shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4. The demo02-02.bb program.

Well, this is certainly interesting. Let’s check it out. First, a comment is written to describe the program. This is good practice and should be used on most programs. Next, I initialized two variables: favnum and coolnum. Then, I called the Print function. The string variable begins with the static text "I like" and then displays favnum. To display favnum, you use the concatenation operator (+). The concatenation operator links separate strings together; in this case, it displays the variable favnum. It finishes out the first Print statement by displaying "And I like" + the variable coolnum.

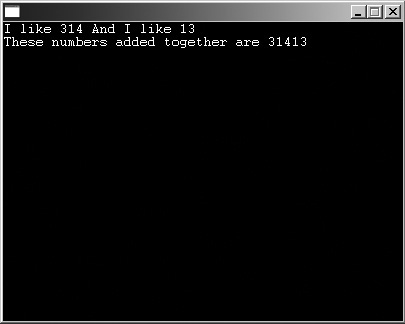

The next Print statement displays "These numbers added together are" and shows 327, which is equal to 314 + 13. However, try removing the parentheses around favnum and coolnum. A strange answer comes up when these parentheses are removed: 31413! (See Figure 2.5.)

Figure 2.5. Demo02-02.bb without parentheses.

The reason for this strange answer is that without the parentheses, the addition operator (+) is interpreted as the concatenation operator due to the context in which it is used. Because there are no parentheses, the operator simply adds the string “13” to the end of the string “314” and displays it as a string rather than an integer. The only way to fix this problem is to use parentheses.

Here is an example using only string variables.

;demo02-03.bb - adds strings together string1$ = "I " string2$ = "like " string3$ = "programming!" ;concatenate the strings completestring$ = string1$ + string2$ + string3$ ;print 'em out Print completestring$ Delay 5000

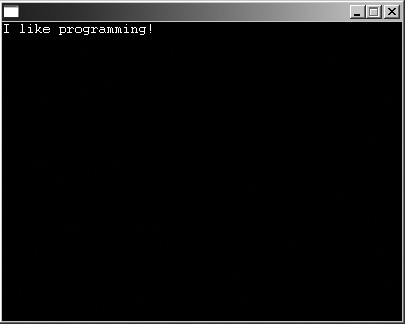

In this program, a set of single words are created and joined together in the completestring$ variable using the concatenation operator. As you can see in Figure 2.6, "I" + "like" + "programming!" becomes "I like programming!".

Figure 2.6. The demo02-03.bb program.