8

Is There Local Content on Television for Children Today?

Katalin Lustyik and Ruth Zanker

ABSTRACT

This chapter explores the dichotomy between “local” and “global” television content targeting children in the context of debates on media globalization. Our three case studies – TVNZ6 in New Zealand, Minimax in Eastern Europe, and Al Jazeera Children's Channel in the Middle East – focus specifically on locally produced content offered on thematic children's television channels launched to promote the cultural heritage of a particular nation or region. Operating in small but radically different media environments on different continents, these channels provide concrete examples of how local content is conceptualized and what types of content are being offered and produced for children today.

At this moment, there are nearly 2 billion children under the age of 18 worldwide who are targeted by an increasing number of television programs and dedicated children's channels. As such globally circulated programs and networks expand their reach using multimedia platforms, the question becomes: Is there a need – and room for – locally produced television content for young people? From the perspectives of many governments, the public, and producers and broadcasters, locally produced content developed with the interest, perspective, and views of local children in mind can provide them with a sense of their own place in an increasingly complex world. But how is local television content defined in different parts of the world today, and what kind of programs are actually being produced?

This chapter explores the dichotomy between “local” and “global” television content targeting children in the context of debates on media globalization. Our three case studies focus specifically on locally produced content offered on thematic children's television channels launched to promote the cultural heritage of a particular nation or region. They operate in radically different media environments in three distinct regions of the world: the Middle East, postcommunist Europe, and the South Pacific. With the selection of our case studies we hope to provide concrete and distinct examples of how local content is conceptualized and what types of content is being produced for children today in various parts of the world. The first case study examines a thematic local children's television network in New Zealand. TVNZ6 was a noncommercial digital channel that operated as part of a much attenuated public service broadcasting sector. This channel was dropped in February 2011, to reappear in May 2011 as Kidzone24 on the majority Murdoch-owned Sky platform. The second case study focuses on children's television content in Hungary, and more specifically on Minimax Hungary, an Eastern European regional commercial network targeting children growing up in a dynamically transforming postcommunist media system. The third case study looks at television content produced in the Middle East for children by focusing on Al Jazeera Children's Channel (JCC), a pan-Arabic non-commercial edutainment channel established in Qatar and funded by the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development (QF).

Undertaking this project has involved the collection and analysis of different types of data. In-depth interviews were conducted with representatives of the children's television industry such as producers, network officials, and media researchers in three locations – Hungary (between 2000 and 2002), Qatar (in 2010), and New Zealand (between 2007 and 2011) – with the aim of gathering valuable insight from those whose work is connected to children's television in their respective regions. In addition, we have collected and analyzed data from the television schedules of three thematic children's channels between the spring of 2010 and summer of 2011: TVNZ6, Minimax Hungary, and Al Jazeera Children's Channel. We specifically examined and compared the programming offered during the last week of April 2010 in the case of each channel. In each location, we also monitored other television channels that regularly offered children's programming between the spring of 2010 and summer of 2011, and gathered some concrete examples from their early June 2011 schedules. The websites of the three television networks – tvnz6.co.nz (and subsequently tvnz.co.nz/kidzone24), minimax.hu, and jcc.net – as well as regional media watch groups were also monitored on a regular basis for information related to program content.

The chapter is divided into four main sections. The first provides a general overview of the key characteristics of the global children's television landscape. The second section focuses on what local television content is and why it is still relevant. It also explores the dichotomy between “local” and “global” content in the context of debates on media globalization. The third section looks at television content offered to children in three culturally, politically, and linguistically distinct regions of the world: the South Pacific, Eastern Europe, and the Middle East. Through our three case studies we examine the content of three thematic children's television channels, each of them launched during the last decade to promote the cultural heritage of the specific nation or region. The fourth section describes the similarities and key differences between how local content is conceptualized and offered by the selected television networks.

The Children's Television Landscape in a Global Context

The current global children's television landscape is incredibly diverse and dynamic. Some of the recent and most visible developments include young television viewers being offered more programming than ever before, with animated shows constituting the largest, fastest-growing, and often most creative portion of the programming (Messenger Davies, 2010). Television networks dedicated solely for this niche audience have become increasingly prominent and influential features of audiovisual markets around the world. The content of the most prominent globally available television networks such as Disney, Nickelodeon, and the Cartoon Network is produced in the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom (e.g., Steemers, 2010).

Nations who dominate production also tend to dominate global cultural trade. The global production and programming ecologies for early childhood and older children are diverging in important ways. Early childhood programs are increasingly considered to be among the most exportable and commercially exploitable forms of children's television because they have several market advantages. They are set in largely uncontested early childhood landscapes and young children love viewing repeated programs. Such programs also appeal to new audiences every two years, which creates a short cycle and is cost effective for programmers, and animation and puppet shows can be cheaply dubbed (Steemers, 2010). For commissioners the initial costs may be high, but the returns from sales and the efficiencies generated by repeats for successful programs are enticing. It is not surprising that Teletubbies, Dora, the Explorer, or Curious George dominate global television services. The older school-aged group, arguably, makes for a much less homogeneous global audience, although some shows such as SpongeBob SquarePants have garnered a global audience. Audience provision becomes politically fraught as young people naturally begin to explore their individual agency and experiment with culture and identity (Australian Communication and Media Authority [ACMA], 2007).

Thematic channels targeting children constitute one of the fastest-growing and most dynamic sectors of the global media industry today (Steemers, 2010). Many children in Europe have access to the dozens of children's channels. In the last decade, the number of dedicated channels targeting young viewers has skyrocketed and they have become increasingly diversified based on their primary goals, funding mechanisms, branding activity, target audiences, geographical reach, content, and use of digital platforms. There are age-specific (Baby TV for toddlers) and gender-specific (Disney DX targeting boys) channels, publicly funded channels (CBBC in the UK, Kinderkanal in Germany), and national channels funded and controlled by governments (Central TV's Children's Channel in China). And we can find channels associated with a particular country (TVNZ) or region (Minimax in Eastern Europe, Al Jazeera Children's Channel in the Middle East). The most prominent players, however, are the globally circulated channels owned by US-based transnational media corporations such as Viacom's Nickelodeon, Time Warner's Cartoon Network, and Disney. They are considered to be the “masters of the children's television universe” that have preserved their dominant position and generated “impressive profit margins” even though the competition has increased during the last years (Westcott, 2008). With “the accumulation of enormous capital, marketing experience and the control of the global market” they have a “tremendous competitive edge” to expand on a global scale (Wu & Chan, 2008, p. 198).

Recent global television hits for this age group are often high quality and based on extensive formative research. Nickelodeon's globally circulated content tends to reflect the tastes and desires of children tested in the United States, but it is branded as content that would appeal to children in many parts of the world (Hendershot, 2004). Nickelodeon is marketed as “the world's only multi-media entertainment brand dedicated exclusively to kids,” and, according to Viacom's interactive global map, Nickelodeon has a “global reach” with a few exceptions such as Greenland (Viacom, 2010). What the map is not designed to show is the amount of locally produced content offered in various regions. According to Sandler (2004), the majority of Nickelodeon channels operating around the world had a strong US flavor with 75% of the programming composed of Nick US originals. As our sample schedules show, there is minimal or no local content offered on the Nickelodeon channels in New Zealand, Hungary, and the Arab world. As high production quality and well-researched Nickelodeon and Disney programs circulate globally, is locally produced television content still important?

The Importance of Local Content

Governmental and scholarly debates as well as public concerns have long focused on the asymmetries in the flow of global media content targeting children and young people. Before we examine local television content offered in our selected regions, this section briefly describes typical government officials, broadcasters, and scholarly positions on the importance of offering local content for children, as well as young people's perceptions of local and globally circulated television content.

For some public broadcasting advocates, such as a former head of Children's Television at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the asymmetries in global media content flow targeting young people mean that “in many parts of the developing world, children are moving from local radio to Disney or Fox without having any television which is specific to them and their culture” (Home, 1997). By contrast, national media-funding policy for children's television programming in many parts of the world is predicated on telling stories and hearing voices that reflect local cultures. To a former managing director of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), domestic children's television is a “vitally important programming territory” that has to be “protected”:

I'm not suggesting the influence being detrimental, but it's not a national Australian influence and it's not conceived or developed with a view to telling our stories [...] It was incredibly important and absolutely fundamental that Australian children received Australian programs scheduled by Australian producers and made available on Australian-owned and operated services. (Shier, 2001, para. 3)

Some media scholars such as Nyamnjoh (2002) argue that global media content can create rather explicit “hierarchies” by classifying children as “primary” and “secondary” media consumers:

Children who have access to global media content that is produced without their particular interest in mind are often victims of second-hand media consumption even as first-hand consumers, since the media content at their disposal seldom reflects their immediate cultural contexts. They may have qualified as global consumer citizens thanks to the purchasing power of their parents and guardians, but culturally, they remain consumer subjects, and must attune their palates to the diktats of undomesticated foreign media dishes. (Nyamnjoh, 2002, p. 43, emphasis added)

Children in many countries with small or underfinanced media markets can be “best conceptualized as being at the end of hybrid cultural flows” (Zanker, 2002, p. 78).

Even in nations with strict local content quotas, requirements for license renewals, and provision of comparatively generous funding sources for children's programming, local content today constitutes a very small portion of children's media choices. Now with national channel operators under ratings pressure from global branded niche channels that often lock up first-play hits, there is growing resistance to compliance. When the United Kingdom regulator removed children's provision from core licensing requirements, ITV, the country's largest commercial television network, stopped production and limited the repeat scheduled hours of content for children because they were perceived to be costly (Steemers, 2010). National dedicated children's channels program a mix of quality global and local reruns and more rarely commission new work. The two public digital children's channels in the United Kingdom, CBBC and CBeeBies, show predominantly repeated programs, over-whelmingly animated and many from the United States, while first-release programs by British producers amounted to 1% of transmission time (UK Office of Communications [OFCOM], 2008). The newly launched Australian public digital channel ABC3 is not equipped to do better than the BBC's children's channels in meeting Australian children's media needs (Edgar, 2009).

Documents such as UNESCO's Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions (2005) demonstrate a rather universal desire to create a balance between the protection of local cultures and the promotion of cross-border flows of cultural content, but it is largely contested how this can be achieved successfully. The United Nations' Convention on the Rights of the Child (1990) supports the media rights of children. Article 17 describes rights over access to information and material from a diversity of national and international sources, especially those aimed at the promotion of children's social, spiritual, and moral well-being and physical and mental health. This, importantly, includes the linguistic needs of indigenous children and access to their local cultures and information (UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1990).

The Convention is an ambiguous document, however. The tendency of the discourse of children's rights has been to admit children to the public sphere. It treats them, in certain respects, as citizens, as if children's views should be given due consideration in processes that affect their interests. This would appear to respect the right of children's voices to be heard within the cultures and communities in which they physically live and where they have tangible opportunities for cultural and political agency. This embraces provision of content in indigenous languages and access to local cultures and information. At the same time, “the Convention affirms the ‘freedom’ of children to seek, receive and impart information of all kinds [...] either orally, in writing, or in print, in the form of art, or through any media of the child's choice” (Buckingham, Davies, Jones, & Kelley, 1999, p. 169). Those targeting child consumers draw on freedom of speech principles to argue that children are active audiences whose agency should be respected, especially in terms of their preferences within popular consumer culture (Zanker, 2004).

Do children care for local content? Ethnographic and audience studies that focus on the children's consumption of local and globally circulated media products often reveal that they do not necessarily distinguish between them. Some scholars contend that while children might be consuming the same media content and using the same communication technologies, it does not necessarily result in cultural homogenization: “Conversely, the world is becoming ever more culturally diverse despite what seems like a common culture of consumption and style” (Lemish, Drotner, Liebes, Maigret, & Stad, 1998, p. 554). Others argue that given the global influence of a handful of media conglomerations, “[W]e might all be consuming Disney in complex and ambivalent ways, but in the end we are all still consuming the same thing. The space for alternative childhoods, for alternative stories to be told, may be steadily reducing” (Buckingham, 2001, p. 294).

The preference for global or local content is not a zero-sum game. Children's heightened interest in shared popular global culture does not preclude interest in the local and particular and pleasure in sharing these stories. Research also tells us that viewers, young and old, usually prefer familiar settings and context, and their native language if the story is interesting and of high production quality (Thickett, 2007). Children want to experiment with their emerging sense of social agency and explore a range of identities within media spaces. Many of the contradictions discussed in this section as we explored the dichotomy between “local” and “global” television content for children are also revealed in our three case studies.

Local Content on Local Thematic Television

Hungary, Qatar, and New Zealand, along with many other countries, have been thoroughly integrated and incorporated into the world communication infrastructure, with a substantial amount of audiovisual programming targeting children coming from abroad. Our case studies examine the availability of locally produced television content in three different media institutional settings: an increasingly fragile national public service broadcasting sector (TVNZ6), regional commercial network owned by transnational media conglomeration (Minimax Hungary), and regional free-to-air noncommercial network funded by a private nonprofit organization (Al Jazeera Children's Channel). In each of our cases studies, we provide some basic information about the country's media system and then focus particularly on local versus nonlocal television content specifically offered to young viewers in general and in the case of dedicated locally launched channels.

New Zealand's TVNZ6

New Zealand is a tiny nation of 4 million people, of which just over 850,000 are children aged up to 14 years. Television remains their top entertainment choice (Lealand & Zanker, 2008). New Zealand has a deregulated broadcasting system where the principle of “countering market failure” is a central plank of its broadcasting policy. There are no quota requirements or license renewal public service requirements. The result is a minimalist public service broadcasting model which places a sense of national identity as central to its mission. The 1989 Broadcasting Act put in place the local content broadcast funding commission, New Zealand On Air (NZoA), which funds, on a contestable basis, locally produced children's programs to be shown on TV2 and TV3, two national commercial free-to-air networks. NZoA is required to consider the size of the audience that will benefit from the programming it funds, as well as issues of diversity. It is unlikely that locally produced New Zealand children's television would exist without NZoA. Currently, approximately US$13 million is allocated for the creation of local content for children and young people.

The local children's production ecology is fragile in New Zealand. National broadcasters have suffered a loss in advertising revenue, new voluntary codes around food advertising limit the range of advertisers, and child audiences are inexorably shifting to global satellite channels. Disney Channel, Cartoon Network, and Nickelodeon are overseas feeds, with any local content strictly related to marketing and branding of the channel. As an example, we include the 24-hour programming schedule of Nickelodeon New Zealand from June 2011 and added the country of production for each show (see Table 8.1). The majority of the programs, as can be seen in Table 8.1, are produced in the United States, with a few exceptions such as Hi-5 (Australia), Shaun the Sheep (UK), and Degrassi: Next Generation (Canada).

Table 8.1 Nickelodeon New Zealand's schedule (June 7, 2011)

Source: Nickelodeon NZ program schedule from nick.co.nz.

Perhaps the closest to public service provision is found on Maori Television, funded directly by the government to foster indigenous Maori culture and language. However, an initiative in 2005 saw the government committing funding to the setting up and running costs for two digital noncommercial public service channels available through a “freeview” digital set-top box, but only for six years. Both channels lean heavily on the “mothership” of state broadcaster Television New Zealand (TVNZ) for infrastructure and are part of TVNZ's market strategy of “content on every screen.” One of these digital channels was TVNZ6, a dedicated child- and family-oriented network that reached 60% of New Zealand homes. There were three zones on TVNZ6: early childhood-focused Kidzone from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m., TVNZ Family until 8.30 p.m., and then TVNZ Showcase until midnight.

The programming strategy on TVNZ6 was for commercial-free, educational programming designed to be enjoyed by parents and children together. Local content consisted of repeats of the many early-childhood programs commissioned over 20 years by commercial national broadcast channels from NZoA funding. These included the first locally designed early-childhood program commissioned by TV3 in the early 1990s, You and Me. Other repeated NZoA-funded early-childhood programs include The Big Chair, Bumble, The Dress Up Box, and Buzz and Popp. Schedules were rotated and repeated over the week. “Quality” imported shows like Rupert Bear, Fireman Sam, Postman Pat, Chuggington, The Mole Sisters, Angelina Ballerina, Caillou, Berenstain Bears, and The Wiggles also rotated in the schedule.

Table 8.2 TVNZ6 programs divided by origin of production (week of April 25, 2010)

| Local content | |

|

(times not listed but repeated as cycles of programming from 6:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. family time) Milly Molly (2006–8) Zip and Mac 3D (from book) (2008) Puzzle Inc The Big Chair (1997–2000) The Go Show (2005–6) Giggles (2010 for TVNZ6) Massey Fergusson (2002–4) Buzzy Bee and Friends (2009) P.e.t. Detectives (2003) Freaky (2003) |

|

| Family-appeal local shows | |

| 6:30 p.m. | Just the Job |

| 7:00 p.m. | Park Rangers |

| 7:30 p.m. | Anzac Tales from Te Papa |

| 8:00 p.m. | The Kiwi who Saved Britain (dramatized life of Keith Park) |

| 9:00 p.m. | Mirror Mirror (kidult drama) |

| Nonlocal content | |

|

The Mole Sisters (from book), animation (Canada, 2003) Rupert Bear (from book), animation (Canada, 1991–7) Chuggington, animation (UK, 2008) Zoomix, animation (Spain, 2007) Caillou (from book), animation (Canada, 2008) Roll Play, series (Canada) Fireman Sam, animation (UK: Wales, 1985–) Spider 2d, animation (UK, 1991–) Hurray for Huckle (from book), animation (Canada, 2007) Eco Company (teens) (US, 2009) The Animal Shelf, animated (US, 1990s) Story of Tracey Beaker (from book) (UK, 2001–8) 24Seven, boarding house drama (UK, 2002–6) Roman Mysteries (from book) (UK) |

Source: Press television listing guide.

Most local shows in the sample week from 2010 were reruns of children's programs funded in past years by NZoA (see Table 8.2). Only two shows were funded using public funding allocated to TVNZ6: Giggles, a sketch comedy show for early childhood, and Kidzone, a presenter-driven linking show that repeated three times a day (at 8.35 a.m., 12.35 a.m., and 4.35 a.m.). Four series of 150 (5-minute) low-cost episodes of Kidzone were commissioned. Each week has a different theme and its young adult presenters, a Pacific mix, present “live” music, dance, and song in a range of languages. The producer, director, and team are early-childhood trained. Presenters suggest activities for when television is turned off and validate children in their cultural Pacifica diversity. New Zealand children contribute stories to share. Phillips, the show's producer, uses television to “scaffold learning” (M. Phillips, personal communication, 2010). Anzac Tales from Te Papa, screened in the evening and targeting families, was a special compilation of military-related Tales from Te Papa episodes in commemoration of Anzac Day (Australia and New Zealand memorial day).

TVNZ6 commissioned only one show for tweens, the short form In Between, which included episodes on sibling rivalry, being gay, depression, and drugs. In Between linked to Bebo, a popular social network site, but lack of promotion meant that the power of interactivity was never really tested. Kidzone morphed into TVNZ6 Family. TVNZ6 Family only shows repeated, previously viewed local content, such as “kidult” dramas like Being Eve, Holly's Heroes, and Mirror Mirror, also commissioned earlier from the children's fund of NZoA. Other locally produced content includes shows such as Just the Job (career show), Pioneer House (historical reality show), and Korero Mai (learning Maori). Some local content has been funded in conjunction with the national museum Te Papa and the Department of Conservation. These shows recirculate within these institutions and via DVDs in schools.

TVNZ6 was unpromoted by its “mothership,” the national TVNZ network, yet still gained a fervent following. In February 2011, after data for this study had been collected, TVNZ announced that TVNZ6 was to close down as a free public service channel. In its place TVNZ negotiated a profit-share deal with the pay platform Sky. In May 2011, Kidzone24 appeared as a 24-hour channel as part of the basic Sky satellite package that reaches 49% of New Zealand homes. This deal caused some controversy, given the investment from public funds in the local programs on its schedule, and fans built a Facebook page (facebook.com/keepkidzone) to share their concerns. The programming of Kidzone24, similarly to TVNZ6, is a combination of older and newer local content and nonviolent educational programs that are predominantly North American and European productions and co-productions (see Table 8.3).

Minimax Hungary

Hungary, a postcommunist nation of 10 million, has one of the most highly developed television markets in Eastern Europe, dominated by two foreign-owned commercial broadcast channels, RTL-Klub (RTL Group) and TV2 (ProsiebenSat1). The public service broadcaster Hungarian Television, after being in a monopoly position for over 40 years during the communist era, saw its national viewership decline to 13% during the last decade (MAVISE, 2010). While the production of children's programming existed as a core service since the introduction of television in Hungary in the 1950s, today, internationally circulated popular shows dominate the children's television sector.

Table 8.3 Kidzone24 programs divided by origin of production (week of launch, May 1, 2011)

| Local content | |

|

Kidzone with Kayne (2010) (every half-hour) The Go Show (2005–6) Zip and Mac (2008) The Dress Up Box (2001) Buzzy Bee and Friends (2009) Giggles (2010) You and Me (1993) The Wot Wots (2009) |

|

| Nonlocal content | |

|

Guess with Jess (UK, 2009) Boblins (UK, 2006) Babar and the Adventures of Badou (Canada/France, 2010) Enjie Benjy (UK, 2002) Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service (UK, 1981) Fireman Sam (UK: Wales, 1985) Angelina Ballerina (UK, 2002) Berenstain Bears (US, 2003) Captain Mack (UK, 2008) Zoomix (Spain, 2007) Chuggington (UK, 2008) Miss Spider's Sunnypatch Friends (Canada, 2004–) |

Source: Kidzone24 program schedule available on TVNZ's website.

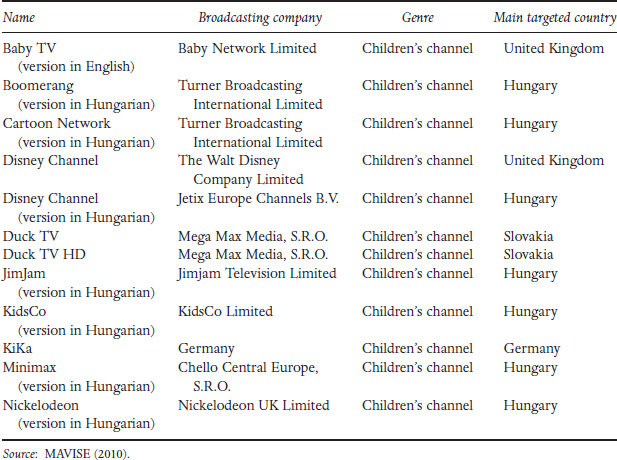

Currently, about a dozen niche television channels compete for young viewers, among them Boomerang TV and Cartoon Network owned by Time Warner, Jetix, owned by Disney, KidsCo, owned by NBC Universal, and Minimax and JimJam, owned by Liberty Global (see Table 8.4).

Shows from the extensive library of Nickelodeon, the Cartoon Network, and Disney have been offered on national broadcast channels in Hungary since the mid-1990s, dubbed in Hungarian. Today, these US-based networks are available as stand-alone channels, as can be seen from Table 8.4. The majority of children's channels operating in Hungary today provide a local-language feed and a website but no locally produced content. As an example, we include the programming schedule of Nickelodeon from June 2011 (see Table 8.5). The titles are translated from Hungarian to English and the country of production is indicated for each show. As Table 8.5 shows, the Nickelodeon channel available in Hungary had no locally produced content and relied heavily on US Nickelodeon productions. Many of its programs overlapped with those offered on Nickelodeon New Zealand's channel.

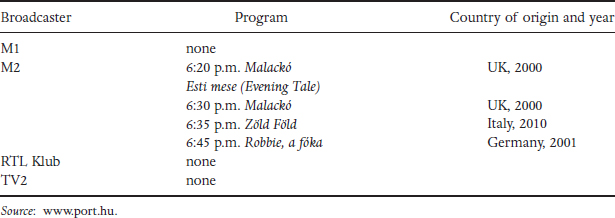

While the total number of shows offered for children has grown exponentially during the last 20 years in Hungary and other Eastern European countries, there is very little locally produced content available. Even though local content quotas for broadcasters exist in Hungary, both public and commercial national broadcasters claim that they do not have the financial resources to invest in “the revitalization” of local children's programming funded by the state during the communist era (ORTT, personal communication, 2002). While in 2002 the Hungarian National Radio and Television Commission (ORTT) voted to allocate a small portion of broadcasting funds to support the production of local children's programming, with the Ministry of Culture also creating a fund to promote and protect local cultural identity by means of locally produced television programs, the revitalization has not happened yet (Országos televiziók, 2002). As an example, we include weekday programming schedules of the main national broadcasters: public service broadcast channels M1 and M2, and commercial channels RTL-Klub and TV2 (see Table 8.6). Programs offered specifically for children that day consisted of an evening block on M2. None of the programs shown in the block was produced locally.

Table 8.4 Children's channels available in Hungary (in spring 2011)

The only channel that has succeeded in creating a “local feel” is Minimax Hungary. Symbolically, as a present for Hungarian children from Santa Claus, Minimax was launched on December 6, 1999, targeting the 4 to 14 age group. According to its Hungarian founders, the idea of the television channel came from a group of enthusiastic friends who wanted children to be able to watch their favorite programs, which simply disappeared from television screens after the privatization and deregulation of Hungary's media system in the 1990s (Minimax, personal communication, 2002). The group examined each television channel available in Hungary at the time and came up with services for children that the others lacked: nonviolent, educational but simultaneously entertaining programming that originated primarily from Europe, with special emphasis on Eastern European puppet and animated programs that were popular during the 1970s and 1980s. Minimax's immediate success according to its program director was based on its nonviolent and local and regional content, as well as its continuous contact with viewers (Lazar, 2003). In its early years the channel emphasized that over 80% of the programming originated from Europe, with 20–25% of it coming from Hungary and Eastern Europe, such as the once popular Polish cartoon Lolka and Bolka (Minimax, personal communication, 2002). Since the mid-2000s, Minimax's programming schedule has relied heavily on global hits from the United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Australia such as Postman Pat, Global Grover, Elmo's World, My Little Pony, Franklin, and the Magic School Bus.

Table 8.5 Nickelodeon's Hungarian programming schedule (June 6, 2011)

| 4:00 a.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 4:25 a.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 4:50 a.m. | Ben és Holly apró királysága (Ben and Holly's Little Kingdom) (UK, 2009) |

| 5:00 a.m. | Dóra, afelfedező (Dora the Explorer) (US, 2000) |

| 5:25 a.m. | Go, Diego! Go! (Go Diego Go!) (US, 2005) |

| 5:50 a.m. | Ben és Holly apró királysága (Ben and Holly's Little Kingdom) (UK, 2009) |

| 6:15 a.m. | Vissza a farmra (Back at the Barnyard) (US, 2007) |

| 6:40 a.m. | A Madagaszkár pingvinei (Penguins of Madagascar) (US, 2008) |

| 7:05 a.m. | Macseb (Cat Dog) (US, 1998) |

| 7:30 a.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 7:55 a.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 8:20 a.m. | Ni Hao Kai-lan (US, 2008) |

| 8:45 a.m. | Go, Diego! Go! (Go Diego Go!) (US, 2005) |

| 9:10 a.m. | Minimentők (The Wonder Pets) (US, 2006) |

| 9:35 a.m. | Ben és Holly apró királysága (Ben and Holly's Little Kingdom) (UK, 2009) |

| 10:00 a.m. | Dóra, a felfedező (Dora the Explorer) (US, 2000) |

| 10:25 a.m. | Dóra, a felfedező (Dora the Explorer) (US, 2000) |

| 10:50 a.m. | Jimmy Neutron kalandjai (The Adventures of Jimmy Neutron: Boy Genius) (US, 2002) |

| 11:15 a.m. | Az életem tinirobotként (My Life as a Teenage Robot) (US, 2003) |

| 11:40 a.m. | Avatár – Aang legendája (Avatar: The Last Airbender) (US, 2005) |

| 12:05 p.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 12:30 p.m. | Drake és Josh (Drake & Josh) (US, 2004) |

| 12:55 p.m. | iCarly (US, 2007) |

| 1:20 p.m. | Tökéretlenek (Unfabulous) (US, 2004) |

| 1:45 p.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 2:10 p.m. | Tündéri keresztszülők (The Fairly OddParents) (US, 2001) |

| 2:40 p.m. | Fanboy and Chum Chum (US, 2009) |

| 3:05 p.m. | Avatár – Aang legendája (Avatar: The Last Airbender) (US, 2005) |

| 3:30 p.m. | A Madagaszkár pingvinei (Penguins of Madagascar) (US, 2008) |

| 3:55 p.m. | iCarly (US, 2007) |

| 4:20 p.m. | iCarly (US, 2007) |

| 4:45 p.m. | Drake és Josh (Drake & Josh) (US, 2004) |

| 5:10 p.m. | Drake és Josh (Drake & Josh) (US, 2004) |

| 5:35 p.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 6:00 p.m. | SpongyaBob Kockanadrág (SpongeBob SquarePants) (US, 1999) |

| 6:25 p.m. | Macseb (Cat Dog) (US, 1998) |

| 6:50 p.m. | Tündéri keresztszülők (The Fairly OddParents) (US, 2001) |

| 7:15 p.m. | A Madagaszkár pingvinei (Penguins of Madagascar) (US, 2008) |

| 7:40 p.m. | iCarly (US, 2007) |

| 8:05 p.m. | Drake és Josh (Drake & Josh) (US, 2004) |

| 8:30–9:00 p.m. | Az alakulat (The Troop) (US/Canada, 2009) |

Source: www.port.hu.

Table 8.6 Weekday children's programming schedule on main Hungarian national broadcast channels (June 6, 2011)

As the sample schedule for April 30, 2010 (Friday) shows (Table 8.7), the majority of the programs came from the United States and Western European countries, with the exception of Bob and Bobek (Bob a Bobek, králici z klobouku, 1979), a Czech animation popular throughout Eastern Europe, including Hungary, during the 1980s. Many of the programs listed in Table 8.7 were repeated during the day (the same or a different episode).

There were four 5-minute-long programs produced specifically for Hungarian children between 6 a.m. and 8 p.m. during the sample week (see Table 8.7). Minimax Hiradó (Minimax News) is a monthly 5-minute-long magazine-style program with two hosts produced by the network. The short segments focus on local artists, local books, or cultural events, some of which seem to target parents rather than children. During April 2010, five episodes of the show rotated daily in the schedule. The program series Te már olvastad? (Have you read it?) started in the fall of 2009 as part of the network's campaign, in partnership with libraries and publishers, to promote books and reading among a new generation of children who preferred television and gaming. Hungarian celebrities, including musicians, television hosts, politicians, and sports personalities, were asked to talk about their favorite childhood books and the importance of reading.

Table 8.7 Minimax Hungary programming divided by country of origin (April 30, 2010, Friday)

| Local content

Minimax Hiradó (Minimax News) (5 min) Te már olvastad? (Have you read it?) (5 min) Magyar Népmesék (Hungarian Folk Tales) (5 min) Alma-klip (Music video clip) (5 min) |

| Regional content (dubbed)

Bob and Bobek (Bob a Bobek, králíci z klobouku) (Czech, 1979, 8 min) |

| Nonlocal content (dubbed)

My Little Pony (US, 20 min) Martha Speaks (US, 25 min) Elmo's World (US, 15 min) Global Grover (US, 5 min) Adventures of Bert and Ernie (US, 10 min) Mary-Kate and Ashley in Action (US, 30 min) Viva Pinata (Canada/US, 15 min) Busytown Mysteries (Canada, 25 min) Chuggington (UK, 10 min) Mr. Bean (UK, 10 min) Timmy Time (UK, 15 min) Roary the Racing Car (UK, 10 min) Fifi and the Flowertots (UK, 10 min) Lenny and Tweek (Germany, 5 min) Leo and Fred (Germany, 5 min) Once Upon a Time... Man (France, 25min) Pat & Stan (France, 5 min) Geronimo Stilton (Italy, 25 min) Bindi, the Jungle Girl (Australia, 25 min) |

Source: Minimax program schedule, minimax.hu.

Alma-klip is a music video clip created by the network working in partnership with the popular Hungarian children's music group Alma (Apple). The latest Minimax in-house production launched in 2011, Minisef (Minichef), teaches children basic cooking techniques that do not require adult assistance in the kitchen.

The last local program, scheduled twice a day during the sample week from 2010, was Magyar Népmesék (Hungarian Folk Tales), a 10-minute-long animated series that used a local folk art visual style and archaic folk-style narration. The series has been around for decades and is considered a significant part of the nation's audiovisual heritage. It is among the few television programs that survived regime changes in Hungary, with a total of 89 episodes created between 1978 and 2006.

Minimax has become an influential local brand in children's media culture in Hungary and was celebrated as an Eastern European success story at the end of the 1990s. Since 2007, however, Minimax has been fully owned by Chello Central Europe, the Europe-based content division of Liberty Global, a US-based transnational media company. Today Minimax is a leading commercial pan-regional network with local language feeds and dedicated websites provided for Romania, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Moldova, and the former Yugoslavian countries with the exception of Slovenia.

Al Jazeera Children's Channel

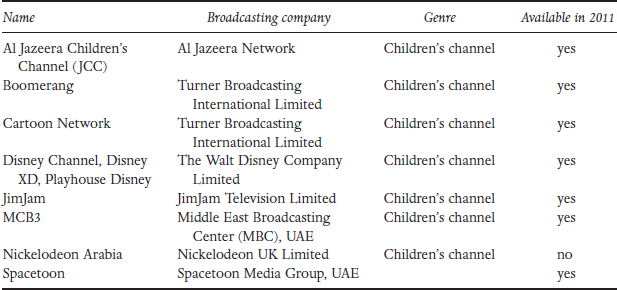

When the Qatari First Lady Sheikha Mozah bint Nasser al Missned suggested the establishment of a noncommercial educational/entertainment children's channel for the region in the early 2000s, it seemed like a “fantasy” in the Arab world (Lepeska, 2010). The lack of consideration by either governments or corporations to fund children's programming meant that locally produced content practically did not exist until the mid-2000s (Kuttab, 2007). Most of the children's programming offered on national television channels across the region was imported and dubbed in local dialects. During recent years, the number of dedicated children's channels in the region exploded with the arrival of US-based branded channels such as Disney XD, Disney Channel, Playhouse Disney, Nickelodeon Arabia, Boomerang, JimJam, and Middle Eastern-based networks including Spacetoon TV, MCB3, and Al Jazeera Children's Channel (JCC) (see Table 8.8).

Table 8.8 Children's channels available in the Middle East between 2008 and 2011

Nickelodeon Arabia, an Arabic-language, free-to-air channel dedicated to Arab children aged 2 to 14 years old, launched in 2008 and included its most popular shows, such as preschool hit Dora the Explorer, SpongeBob SquarePants and Jimmy Neutron for older children, live-action Drake & Josh and Unfabulous, and the Nickelodeon Kids' Choice Awards. The network was a result of a partnership between Viacom's MTV Networks International (MTVNI) and the Arab Media Group (AMG) of the United Arab Emirates. Nickelodeon Arabia went off the air in 2009 as a result of media ownership changes in the United Arab Emirates. As a result, since November 2010 a Nickelodeon block exists on the children's entertainment channel MBC3 that includes SpongeBob SquarePants, The Mighty B!, The Fairly OddParents, Fanboy and Chum Chum, The Penguins of Madagascar, Back at the Barnyard, and My Life as a Teenage Robot. The content of the majority of children's channels is imported and dubbed in local dialects, the exceptions being MBC3, which offers some locally produced shows, and Al Jazeera Children's Channel.

After three years of research and planning, the Al Jazeera Children's Channel (JCC) – a pan-Arabic edutainment network dedicated to children – was launched in September 2005 in Qatar. While the channel shares its name with the influential Al Jazeera news network, also established in Qatar almost a decade earlier, and the board director who also oversees the Al Jazeera Network, they are completely independent from each other. JCC, along with satellite campuses of prestigious US higher education institutions, is located in the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science, and Community Development's flagship project, Education City, on the outskirts of Doha.

JCC, with its primary mission “to encourage the love of learning and discovery” and operating as a noncommercial enterprise funded by the Qatar Foundation, represents a unique model (JCC, personal communication, 2010). The overall mission of the channel, echoing that of the Qatar Foundation, is to make a difference in the lives of Arab youth by promoting “self-esteem, understanding and freedom of thought” (Al Jazeera Children's Channel, 2007). JCC's ambition is to plant “the seed of hope for a better tomorrow, but also for a better Arab citizen” (general manager, quoted in Lepeska, 2010), and to function as a bridge to connect Arab children around the world. JCC's language choice of classical Arabic also aims to promote a pan-Arabic shared identity and serves as a tool for learning or practicing Arabic among the Arab diaspora. Many older children, growing up on programs dubbed in regional dialects, however, find cartoon characters speaking eloquent classical Arabic “strange.” They make fun of their younger siblings, who naturally use the vocabulary previously associated with school (JCC, personal communication, 2010).

Local content is perceived to be crucial for JCC, and its programming consists of 80% local content, with some of the shows produced in-house in one of three high-tech studios. Local production mainly consists of nonfictional programs with a preference for incorporating real children in real-life situations with regional relevance (JCC, personal communication, 2010). According to JCC, “[T]his goal is realized by carefully studying and producing relevant content and ensuring that it resonates with the needs of this target audience's daily life as well as their culture” (Al Jazeera 2006–2011).

Among the most popular JCC-produced programs are game shows such as Ad Darb, in which teams of children compete in various subject areas such as history, science, and geography in front of a live studio audience. JCC also offers thematic magazine shows for the first time in the region. Its weekly debate show Nadra Ala encourages children to speak up freely and form their own opinions on a variety of issues. Topics have included female circumcision, illiteracy, and child labor. In each episode regional correspondents share their international reports with the audience and a panel of experts. The show Atfal Al Mahjar is a weekly magazine that focuses on the Arab diaspora and on the everyday lives and challenges of Arab children and families living in non-Arab countries. One of the goals of the show is to highlight the Arab family's role in supporting their children's native language, faith, and traditions. Min Al Malaab is a sports magazine, while Al Abtal follows the daily activities of seven groups of student athletes and covers their daily routines, including their educational and cultural lives. Kallemni is a discussion show that features one Arab child in each episode, who shares his or her thoughts, personal insights, emotions, and feelings with the host of the program.

Other JCC programs have more of an entertainment element, such as Ana wa ekhwait, a comedy show depicting family life and values in the region. The main plot focuses on a Syrian family moving to Qatar, where the father working at a radio station encounters comedic characters and situations. Several programs produced in-house, such as Baraem's animated series Nan and Lili, have won over critics at international festivals. While special programming is offered for Ramadan and there is a show about the Qur'an, religious ideals are not allowed to dominate the channel. However, as JCC's general manager explains, “Islam is part of our daily life, it's our religion, and it should be integrated into our content” (quoted by Lepeska, 2010).

As the list of programs aired on April 30, 2010 (Friday) shows (Table 8.9), there were 11 different programs produced specifically for Arab children, several of them shown at least twice a day with different episodes.

Besides the JCC-produced shows, several others are co-produced in partnership with production firms in the United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan. Nonlocal content is “carefully selected” from the international market with the aim to open up “avenues for Arab children to learn about different environments and cultures” (JCC, n.d.). After its initial success, JCC split into two channels in January 2009 to better serve specific age groups. Baraem TV (baraem means “buds”) is aimed at 3- to 6-year-olds, while the original JCC is dedicated to 7- to 15-year-olds. The latest addition to JCC's expansion is Taalam TV, the first Arabic video-on-demand (VOD) educational platform, launched in 2010. It primarily targets schools and educators, who can access detailed programming information and watch the shows at any time.

Today Al Jazeera Children's Channel and Baraem reach 45 to 50 million households in all 22 Arab countries, many parts of Africa, Europe, and Asia. With the planned future launch of an English-language version of Baraem TV, the next territory for the network is North America.

Table 8.9 JCC programs divided by origin of production (April 30, 2010)

| Local content

Min al Malaab (Sports Corner) (15 min) Ana Wa Ekhwati (Me & My Siblings) (15 min) Sahat al Founoun (You Can Do It) (30 min) Min hawlina (Around Us) (30 min) Kallemni (Talk To Me!) (30 min) Aabakira tahado al iaaqa (15 min) Al abtal (The Champions) (15 min) Atfal el mahjar (Children of the Diaspora) (30 min) Circo Massimo (Big Circus) (Italy/localized version, 60 min) |

| Nonlocal content (dubbed)

Ellen's Acres (US, 15 min) Maya and Miguel (US, 30 min) Land Before Time (US, 60 min) Henry's Amazing Animals (Canada, 30 min) Miss BG (Canada, 15 min) The Eggs (Canada/Australia, 15 min) Sitting Duck (US /UK/Canada, 30 min) Benjamin the Elephant (Germany, 30 min) |

Locals Answering Back?

Our three case studies described locally launched children's television channels in different countries representing diverse regions and media models. Minimax Hungary represented a fully commercial channel that achieved immediate popularity with its local flavor. Today Minimax offers very little local content and is owned by a transnational media conglomeration. Hungary's media system, along with many others in Eastern Europe, can still be described as “transitional,” and the mechanisms are not yet in place to support local television content in the current, largely privatized and commercialized media landscape that replaced the state-operated system.

Al Jazeera Children's Channel (and Baraem TV), located in the Middle East, represent a noncommercial model with the primary mission to educate children by providing edutainment programs with as much local flavor as possible. Providing funding for JCC in the oil-and-gas-rich Gulf state, which has the second-highest GDP per capita in the world, seems effortless. The only programming criterion for JCC is to offer quality content that educates and makes better future citizens.

New Zealand's TVNZ6 provided a noncommercial children's service within the public media sector. It lacked the financial deep pockets of Qatar, and could not draw on parental nostalgia for Eastern European shows and the powerful commercial branding employed by Minimax Hungary. But in its short four years, TVNZ6 proved itself to be an innovative local content channel. Run on a shoestring, the noncommercial digital channel had a strong commitment to Pacific-flavored local content. The decision to put publicly funded children's programs behind the paywall of Sky is business driven. It indicates that local content has value to local commercial interests, if only as a point of difference within the overwhelmingly globalized media environment. But will its value be enough to warrant new local commissions? Or will we see repeated circulation of local reruns originally funded for full service national free-to-air channels?

All channels studied were careful to assess the appropriateness of their local and imported shows for their audiences and aspired to an inventory combining gentle entertainment and engaging “edutainment.” Their ratio of local content, however, varied greatly. In the case of Minimax, local content constituted a tiny segment and was repeated endlessly. In the case of JCC, a relatively large portion of its content was produced locally or co-produced with international partners. Continuous government funding has enabled a generation of children since 2005 to acquire Arabic from a popular inventory of programs, some of which are challenging in content. In New Zealand, public service provision and local content are inextricably intertwined. TVNZ6 (and now Kidzone24's) children's schedules draw cost-effectively on two decades of public service inventory as well as on some modest and cost- effective local commissions of its own.

Regardless of the amount of actual local content, all three channels identified the promotion of local culture and cultural heritage as one of their primary missions and described their key programming style as noncommercial and socially responsible edutainment. The interpretation of what constitutes local culture and cultural heritage differs in the three locales. In the case of JCC, the address has broadened from the national to a pan-Arabic region and beyond to the Arabic diaspora around the world. JCC provides a mix of programs that address children primarily as citizens rather than as consumers. JCC's promotion of the classical Arabic language aims to tie more than 20 countries and over 350 million Arabic speakers together in a region, where the language of finance and education is increasingly English. In postcommunist Eastern Europe, Minimax has positioned “our culture” as parental nostalgia for regional classics. Despite its brand being marketed as a local channel, it has not commissioned much new material to appeal to the tastes of current children. Minimax's address has also gradually broadened to include several countries in the region, where children watch the same content dubbed into Romanian, Czech, Slovak, Croatian, and other languages. Minimax's local appeal, in many ways, has been reserved instead for the commodified spaces of interactive clubs and merchandising. New Zealand's TVNZ6 attempted to create a national noncommercial channel for young people living in the Pacific. The verdict is out on the role that Kidzone24 will play in the regional mix as the pay platform Sky lobbies for a share of NZoA free-to-air funding.

One of the similarities we have observed between the three channels is the importance of continuous interaction with children and parents and receiving feedback from them. Both Minimax and JCC also regularly conduct focus group research with children and parents, who are asked to preview programs that the channels plan to acquire or shows in production. In the case of JCC, both quantitative and qualitative studies are conducted regularly in different countries in the region and local educational programs are tested with different audience groups during the production phase. We also found that local content producers face similar challenges in creating shows particularly for older children. In New Zealand, producers say that they understand the needs of early childhood and younger children (e.g., 5- to 9-year-olds) but struggle with what appears to be a relentless shift by preteens (age 10–13) toward global media flows. As one New Zealand producer puts it, “They are a whole new challenge because they don't tell you what they do want, but they do tell you what they don't like and turn off” (J. Morrell, personal communication, 2009).

Conclusion

Television program imports that fill up the majority of children's channels do not constitute a homogeneous group. In the case of TVNZ6, Minimax, and Al Jazeera Children's Channel, television schedules are constructed to draw on so-called “good,” gentle, and educational imports from Europe, Australia, and North America. We found in our interview discussions conducted on three continents that there was often an implicit distinction made between “good” imports, such as Czech fairy tales, and “bad” imports, principally in the form of US and Japanese action-adventure cartoons. Globally circulated channels such as Nickelodeon and Disney also offer quality educational and nonviolent programs primarily for preschoolers and position themselves as socially responsible brands. What sets JCC, Minimax, and TVNZ6 apart are their founding or regulatory cultural objectives. They claim to offer local, culturally specific places for children, away from highly commodified popular culture created for the universal active consumer by transnational media corporations.

That said, however, we have found that nationally based thematic children's channels can also grow into successful market players beyond original national boundaries and even be sold off to transnational media conglomerations. Minimax has laid claim to a regional market share in children's entertainment, and JCC has grown exponentially in market share and popularity across widely flung Arabic-speaking nations. Both can be said to speak back to dominant audiovisual children's flows from the periphery.

The volume of new-release Arabic content available for children on Qatar's JCC after only five years in existence reflects the power to move quickly and decisively to meet cultural and educational objectives, as well as knowledge of local audience needs. Part of this power comes from economic clout. The channel can commission locally and at the global level on its own terms. This is in stark contrast to TVNZ6 in New Zealand, which, despite its valued mix of imported and Pacific regional appeal, could not reach its audience because of lack of government investment. Critically, this includes being able to find traction within the interactive places to which young people are drawn. Hungary's Minimax lies somewhere in between the other two case studies. Currently, it commissions very little new local content, despite it being branded as an Eastern European channel, but it has managed to build a successful multimedia empire in the region.

As we have discovered through our case studies, nationally launched children's channels aim to provide safe and culturally approved places for children, with varying success. Each channel responds in its own unique way to the turbulence of media globalization and cultural and linguistic anxieties stemming from this. While television continues to be the primary media window for children today, and this chapter's main goal was to examine the dynamics of local and global television content, they can only be understood as part of multi-platform media systems. Moving beyond the local–global dichotomy, another important dimension of this debate for future studies would be to examine “the ability or inability” of local content offered on various television channels to “empower” young people “to have influence over the course of their lives” (Kraidy, 2005, p. 151).

REFERENCES

Al Jazeera Children's Channel (JCC). (n.d.). Fact sheet. Retrieved August 8, 2009, from www.jcctv.net/index-20786720210074.21274.html

Al Jazeera Children's Channel. (2006–2011). Al Jazeera Children's Channel. Retrieved April 25, 2011, from http://www.jcctv.net/index-20786720210074.21274.html

Australian Communication and Media Authority (ACMA). (2007). Media and communications in Australian families. Retrieved May 4, 2010, from http://www.acma.gov.au/medialiteracy

Buckingham, D. (2001). United Kingdom: Disney dialectics: Debating the politics of children's media culture. In J. Wasko, M. Phillips, & E. R. Meehan (Eds.), Dazzled by Disney? The global Disney audiences project (pp. 269–296). London, UK: Leicester University Press.

Buckingham, D., Davies, H., Jones, K., & Kelley, P. (1999). Children's television in Britain: History, discourse and policy. London, UK: Macmillan.

Edgar, P. (2009, February). The ABC's cynical proposal for kids' TV. Small Screen, 250, 2.

Hendershot, H. (Ed.). (2004). Nickelodeon nation: The history, politics, economics of America's only TV channel for kids. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Home, A. (1997, July 20). The not so magic roundabout. Independent. Retrieved from LexisNexis database.

Kraidy, M. M. (2005). Hybridity or the cultural logic of globalization. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Kuttab, D. (2007, May 9). Fine-tuning Arab television. Jerusalem Post, p. 15, Retrieved from LexisNexis database.

Lazar, F. (2003, October 23). Mese és valóság a képernyőn. Magyar Nemzet. Retrieved August 8, 2005, from http://www.mno.hu/portal/179168?searchtext=#

Lealand, G., & Zanker, R. (2008). Pleasure, excess and self-monitoring: The media worlds of New Zealand children. Media International Australia, 127, 25–45.

Lemish, D., Drotner, K., Liebes, T., Maigret, E., & Stad, G. (1998). Global culture in practice. European Journal of Communication, 13(4), 539–556.

Lepeska, D. (2010, January 8). How Al Jazeera Children's Channel grew up. The National. Retrieved April 14, 2010, from http://www.thenational.ae/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20100108/FOREIGN/701079841&SearchID=7339251156123

MAVISE Database of TV Companies and TV Channels in the European Union. (2010). Retrieved March 3, 2011, from http://mavise.obs.coe.int

Messenger Davies, M. (2010). Children, media and culture. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Nyamnjoh, F. B. (2002). Children, media and globalisation: A research agenda for Africa. In C. von Feilitzen & U. Carlsson (Eds.), Children, young people and media globalisation (pp. 43–52). Gothenburg, Sweden: UNICEF International Clearinghouse On Children, Youth, and Media.

Országos televiziók – kevesebb agresszió a képernyőn. (2002, October 29). Kreativ Online. Retrieved November 1, 2002, from http://www.kreativ.hu

Sandler, K. S. (2004). A kid's gotta do what a kid's gotta do: Branding the Nickelodeon experience. In H. Hendershot (Ed.), Nickelodeon nation: The history, politics and economics of America's only TV channel for kids (pp. 45–68). New York, NY: New York University Press.

Shier, J. (2001, August 8). Children's TV at risk of US takeover. Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved from LexisNexis database.

Steemers, J. (2010). Creating preschool television: A story of commerce, creativity and curriculum. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Thickett, J. (2007). Children's television in the UK. Retrieved April 24, 2010, from www.ofcom.org.uk/media/speeches/2007/10/slides.pdf

UK Office of Communications (OFCOM). (2008). Future of children's television broadcasting. Retrieved April 25, 2010, from http://www.ofcom.org.uk/consult/condocs/kidstv/

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. (1990). Retrieved September 7, 2009, from http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/crc.htm

Viacom. (2010). Global reach. Retrieved May 3, 2010, from http://www.viacom.com/ourbrands/globalreach/Pages/default.aspx

Westcott, T. (2008, January 31). Masters of the children's television universe [Special report]. Screen Digest.

Wu, H., & Chan, J. M. (2008). Globalizing Chinese martial art cinema: The global–local alliance and the production of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon. Media, Culture and Society, 29(2), 195–217.

Zanker, R. (2002). Tracking the local in the global. In C. von Feilitzen & U. Carlsson (Eds.), Children, young people and media globalisation (pp. 77–94). Gothenburg, Sweden: UNICEF International Clearinghouse On Children, Youth, and Media.

Zanker, R. (2004). Commercial public service children's television: Oxymoron or media commons for savvy kids? European Journal of Communication, 19, 435–455.