1

Mapping the Psychology of Agenda Setting

Maxwell McCombs and Jae Kook Lee

ABSTRACT

In the decades since the seminal Chapel Hill study, agenda setting has evolved into a broad theory and set of hypotheses encompassing five theoretical areas. Characterized by two major trends, all five of these areas remain active research arenas. There is a centrifugal trend, the expansion into new domains and settings far beyond the original realm of public issues. Their counterpoint is a centripetal trend in which scholars have turned their attention inward to further explication of the theory's basic concepts. Much of this work concentrates on the psychology of the agenda-setting process. This chapter examines the role of incidental learning and of moderator and mediating variables in the agenda-setting process, and the impact of agenda-setting effects at both the first and second level on the formation of attitudes and opinions and on subsequent behavior.

Classic Conceptualizations and Emerging Trends

The media lay the foundations of public opinion through their substantial influence on the topics at the center of public attention. This agenda-setting role of the media, its influence on what the public comes to regard as the most important topics of the day, has its intellectual origins in Walter Lippmann's Public Opinion (1922). His thesis that the news media are the bridge between the vast world of public affairs and each citizen's limited perspective of that world was empirically tested by McCombs and Shaw (1972) during the 1968 US presidential election. In the decades since their tightly focused media effects study in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, agenda setting has evolved into a broad theory of communication and set of hypotheses encompassing five theoretical areas.

Characterized by two major trends, all five of these areas remain vigorous research arenas today. There is a centrifugal trend, the expansion of agenda-setting research into new domains and settings far beyond the original realm of public issues. This includes such disparate areas as professional sports (Fortunato, 2001), corporate reputations (Meijer & Kleinnijenhuis, 2006), classroom teaching (Rodriguez, 2004), and religious practice (Hellinger & Rashi, 2009). Their counterpoint is a centripetal trend in which scholars have turned their attention inward to the continuing explication of the theory's basic concepts. Much of this work concentrates on the psychology of the agenda-setting process, which is the primary focus here. After a brief overview of all five areas of agenda setting, this chapter will examine the role of incidental learning and of moderator and mediating variables in the agenda-setting process, and the impact of agenda-setting effects at both the first and second level on the formation of attitudes and opinions and on subsequent behavior.

An Overview

In their seminal study, McCombs and Shaw (1972) compared the pattern of issue coverage in the news media used by voters in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, with the list of issues that these voters considered the most important ones of the day. The media agenda of issues can be precisely described by rank-ordering those issues according to the amount of news coverage that they receive. In similar fashion, the public agenda of issues can be precisely described by rank-ordering the same issues according to the proportion of the public that regards each of these as the most important issue of the day. The high correlation found in Chapel Hill between the news media's issue agenda and the public's issue agenda supported McCombs and Shaw's theoretical proposition regarding the transfer of issue salience from the media agenda to the public agenda. In the decades since the Chapel Hill study, this basic agenda-setting effect – the influence of the media agenda on the public agenda – has been widely replicated in election and non-election settings for a vast array of issues worldwide and with a wide variety of study designs at both the macro and individual level (McCombs, 2004, pp. 30–32).

The 1972 Charlotte presidential election study (Shaw & McCombs, 1977) introduced a second area of agenda-setting theory, the elaboration of contingent conditions that moderate the strength of agenda-setting effects. Although Wanta and Ghanem's (2000) meta-analysis of 90 studies from a wide range of settings found a mean correlation of +.53 with a relatively small variance, there are findings falling well outside this range. For example, Eaton's (1989) individual analysis of 11 issues found correlations between the media and public agendas ranging from −.44 for morality to +.87 for government performance. The median was +.45 for poverty. Foremost among the contingent conditions explaining these variations is the psychological concept of need for orientation (Weaver, 1977), which will be discussed in detail later in this chapter.

The 1972 Charlotte study also introduced the concept of a second level of agenda-setting effects, attribute agenda setting. In theoretical terms, the Chapel Hill study examined basic agenda-setting effects, the transfer of object salience from the media to the public. Object is used here with the same meaning as the term attitude object is used in social psychology. For each object on the media agenda or the public agenda, an agenda of attributes can also be identified. This agenda is the hierarchy of attributes describing the object. For example, during the early months of the US presidential election, the news media present an agenda of candidates. The salience of these objects among the public reflects basic agenda-setting effects. The news media also describe these candidates, telling us about some of their attributes. Just as the rank-order of objects on the media and public agendas are compared to measure basic agenda-setting effects, the rank-order of attributes on the media and public agendas are compared to measure attribute agenda setting, the third area of agenda-setting theory (McCombs, Lopez-Escobar, & Llamas, 2000; Weaver, Graber, McCombs, & Eyal, 1981).

The attributes of an object have both a substantive and affective dimension. Substantive attributes are the cognitive elements of messages that describe the denotative characteristics of an object. Examples of the substantive attributes of a political candidate are ideology and issue positions. For issues, substantive attributes include sub-areas – for example, unemployment and budget deficits as sub-areas of the economic problem – as well as such aspects of an issue as proposed solutions. The affective dimension is the positive, neutral, or negative tone in the descriptions of an object's attributes.

This core theoretical model of agenda setting described by first and second level agenda-setting effects and the contingent conditions moderating the strength of these effects has expanded in recent years to a fourth theoretical area describing the consequences of these effects for attitudes and opinions. All four of these areas will receive major attention in this chapter. A fifth area of agenda-setting theory, which is of less interest here, concerns the origins of the media agenda. This area links agenda setting to another field of mass communication research, the sociology of news.

The tightly focused Chapel Hill definition of agenda setting as the influence of the news media on the salience of public issues among the public has evolved into a broad theoretical perspective defining agenda setting as the influence of major elements in media messages – numerous objects and their attributes – on the salience of these elements among the public. We now turn to the centripetal trend in contemporary research explicating the psychology of this agenda-setting process: the role of incidental learning and of moderator and mediating variables in the agenda-setting process, and the impact of agenda-setting effects at both the first and second level on the formation of attitudes and opinions and on subsequent behavior.

Agenda-Setting Effects from Incidental Exposure

Learning from the media can be either intentional or incidental. While the acquisition of information from the media usually has been conceptualized as an active process, incidental exposure is a viable alternative route to becoming informed. Agenda setting, which involves the acquisition of information about the salience of objects and their attributes, also is possible through both routes, intentional exposure or incidental exposure. At times, people pay close attention to the messages of the media. At other times, attention to these messages is far more casual.

Incidental learning has been discussed under a wide variety of definitions – occurring with minimal conscious allocation of attention (Bettman, 1979), without intent to remember (Jenkins, 1933), and without learning instructions (Frensch, 1998). The exact term used also varies – “low involvement learning” (Krugman, 1965; Robertson, 1976), “spectator learning” (Posner, 1973), and “incidental learning” (McLaughlin, 1965). Despite these variations, all refer to a phenomenon of learning passively about the environment without any significant involvement and intent to learn.

Learning about public affairs is costly when individuals expend resources to actively search for information, argues Downs (1957). However, the public often receives information in the course of doing other things, situations which involve little or no information costs. Popkin (1994) noted that most of the information that citizens use when they vote is acquired as a by-product of activities routinely pursued in their daily lives.

Incidental learning about public affairs that is relevant to the acquisition of knowledge in general, as well as to specific agenda-setting effects, can occur in two different ways: (1) through reactions to interruptions and (2) through low levels of attention (Bettman, 1979). When someone encounters information that attracts his or her attention while doing something else, this interruption can result in becoming informed even though the individual did not actively seek out the information (Beales, Mazis, Salop, & Staelin, 1981). The impact of soft news on people's learning about foreign affairs (Baum, 2002, 2003) is an example of this interruption effect, in that the political information intrudes or interrupts while viewers are seeking casual entertainment or relaxation.

People also can acquire information without being significantly involved. The effects of low attention and low involvement learning are especially relevant for television and online messages in comparison to newspapers. Neuman, Just, and Crigler (1992) found that television is a more powerful tool for people to learn about low salience issues, suggesting learning with low involvement. Acar (2007) found that incidental exposure to text advertising above an online gaming screen made a difference in preference for the advertised product.

Taking a slightly different tack, Frensch (1998) proposed two conditions under which implicit learning can occur: effortlessness and ubiquity. The first condition, effortlessness, is equivalent to Downs' (1957) concept of expending minimal information cost to learn about public affairs. The second condition, ubiquity, is related to the high level of redundancy across news media on the major issues of the day, so that even low levels of exposure are likely to create an awareness of these issues.

For example, people in northern New Jersey were more aware of candidates in a neighboring New York City election than were those in southern New Jersey, though most residents of New Jersey had no interest in the New York City elections (Zukin & Snyder, 1984). Northern New Jersey is in the same broadcasting market as New York City, so that people in the area were exposed to New York election news, regardless of their interest in it.

Marketing research suggests that incidental learning can influence the consequences of first and second level agenda-setting effects for subsequent attitudes and opinions. Janiszewski (1993) found that consumers' attitudes toward products in advertisements were formed in the absence of any conscious processing of the information. After reading a student newspaper that had been manipulated for the study, subjects in the treatment group had higher scores than those in a control group in a series of questions asking about their impressions of the products.

Although considerable evidence suggests that incidental exposure can contribute to awareness about many items, few studies have specifically investigated agenda-setting effects resulting from incidental exposure. One explanation for the paucity of research is methodological. Due to the nature of incidental exposure, it is extremely difficult in survey research to measure whether or how much people are incidentally exposed to messages in the media. However, a recent experimental study demonstrated that individuals incidentally exposed to a public issue were more likely to regard the issue as important than those not exposed to the issue (Lee, 2009). Three groups were incidentally exposed to news stories about the environment, while a control group was not exposed to the stories. The degree and nature of the incidental exposure was manipulated by specific instructions about the task, which was evaluating the usefulness of a college website designed for a general audience. One group only was instructed to navigate the website in order to evaluate its usefulness. Another group was instructed to move the cursor and hover over, but not to click on, banner ads leading to the web pages with the news stories, while the third group was instructed to click on the ads and then read the news stories for 10 seconds. Subjects in the third group, which was directed to pay some attention, but a very minimal level of attention, to the news stories about the environment, had significantly higher scores on the perceived importance of that issue than any of the other groups.

Incidental exposure is the lowest level of attention to media messages, but even this minimal exposure can have significant consequences. We swim in a vast sea of news, absorbing news and information about the world around us through a continuous process of civic osmosis. There is abundant empirical evidence from the earliest days of our field about this learning from an array of media sources rather than a few distinct sources (Lazarsfeld, Berelson, & Gaudet, 1944, p. 122; McCombs et al., 2000, Table 4; Stromback & Kiousis, 2010). In the contemporary setting, Coleman and McCombs (2007) found that although younger adults are not exposed to traditional media as frequently as older generations and use the Internet significantly more, the agenda-setting effects of newspapers and TV news are highly similar across generations. This process of civic osmosis also is buttressed by the finding that the strength of agenda-setting effects are not monotonic with increasing levels of exposure, but frequently reach asymptote after moderate levels of exposure (McCombs, 2004, Box 5.2). The pervasiveness of these patterns of exposure also explains why many agenda-setting research designs do not explicitly measure individuals' level of media use.

Although some minimal level of accessibility is necessary for agenda-setting effects to occur as a consequence of exposure, individual differences regarding the applicability of the information also must be considered.

When people identify interpret or, more generally, respond to a stimulus, what knowledge will be activated and used in their response? In answering this question, accessibility and applicability have been described as two distinct sources of knowledge activation, with salience contributing to knowledge activation through its influence on applicability. (Higgins, 1996, p. 164)

Wanta (1997) and Price and Tewksbury (1997) specifically linked the knowledge activation model to basic agenda-setting effects, evaluative responses by members of the public that a particular issue is an important problem facing the country. Other agenda-setting effects, the salience of various objects and attributes among members of the public, involve similar evaluative judgments.

Need for Orientation

Weaver (1977) introduced the psychological concept of need for orientation to agenda-setting theory in the 1972 Charlotte study of the US presidential campaign. In the civic arena, there are many situations where citizens feel a need for orientation. For example, in primary elections to select a party's nominee for office, there sometimes are as many as a dozen, largely unfamiliar candidates. Because it is a primary election, one orientating cue frequently used by voters, party affiliation, is moot. In these circumstances, voters frequently turn to the news media for orientation. Not every voter feels this need for orientation to the same degree, of course. Some citizens desire considerable information before making their voting decision. Others desire no more than a simple orienting cue. These individual differences in the desire for orienting cues and information explain differences in attention to the media agenda and differences in the degree to which individuals accept the media agenda.

Conceptually, an individual's need for orientation is defined in terms of two lower-order concepts, relevance and uncertainty. Relevance is the initial necessary condition. Individuals have little or no need for orientation in numerous situations in the realm of public affairs because these situations are not perceived to be relevant. In these circumstances, the need for orientation is low or even nonexistent.

Among individuals who perceive the relevance of a topic to be high – to keep matters simple, relevance is dichotomized here as either low or high – the level of uncertainty about the topic must be considered. Sometimes individuals already have all the information they desire, and their degree of uncertainty is low. In this circumstance, people usually do not ignore the news media, but they primarily monitor the news in order to detect any significant changes in the situation at hand. Under these conditions of high relevance, but low uncertainty, the need for orientation is moderate. At other times, such as primary elections, both relevance and uncertainty are high. These circumstances define a high need for orientation.

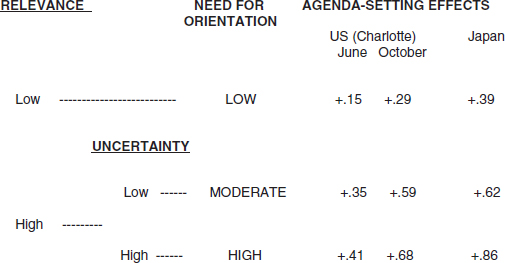

The greater an individual's need for orientation, the more likely they are to reflect the issue agenda of the media. Figure 1.1 outlines the concept of need for orientation and reports the level of agenda-setting effects found amongst Charlotte voters during the 1972 US presidential election. During the summer months as the campaign took shape and, again during the fall campaign, agenda-setting effects increased monotonically with the strength of the need for orientation. This same monotonic pattern also was found in a Japanese mayoral election (Takeshita, 1993) and in many other settings subsequently.

As noted earlier, the core idea of agenda setting refers to the ability of the news media to focus public attention on a few key objects and on the dominant attributes of those objects. These attributes have two dimensions. Substantive attributes refer to specific components of an object, and affective attributes refer to evaluations of the components.

Figure 1.1 Need for orientation and agenda-setting effects.

In accordance with these core concepts of agenda-setting theory, Matthes (2006) developed three sets of measures of the need for orientation. Corresponding to the first level of agenda setting, there is a measure of need for orientation toward the object itself. For example, an individual may believe “it is important for me to observe this issue constantly.” Two additional measures examine need for orientation to specific aspects of an object. These measures take into account the second level of agenda setting, specifically, the substantive attributes of the object under consideration, “I would like to be thoroughly informed about specific details,” and the affective attributes of the object, specifically the journalistic evaluations found in commentaries and editorials, “I attach great importance to commentaries on this topic.”

Matthes (2006, 2008) found that these three sets of measures are highly correlated (the correlations range from +.70 to +.88), and their scores can be summed to create a single need for orientation (NFO) score for each individual. In an investigation of the issue of unemployment in Germany, Matthes (2008) found that the strength of NFO measured by this composite scale predicted basic first-level agenda-setting effects. However, the strength of NFO measured by the composite scale did not predict media effects at the second level of agenda setting, specifically, the affective attribute of the unemployment issue.

Chernov, Valenzuela, and McCombs (2009) examined the comparative strength of the traditional NFO measures and these new NFO measures in predicting agenda-setting effects among participants in a controlled experiment. Both sets of measures independently predicted first-level agenda-setting effects. The comparative strength of the two measures was examined in a series of multiple regressions. When the traditional NFO scale and the new summary NFO scale were entered simultaneously, the traditional NFO scale was the stronger predictor. Further analyses identified the first sub-dimension of the new NFO scale, the sub-dimension directly concerned with first-level agenda setting, as a stronger predictor than either the total scale or the other two dimensions. Finally, comparison of the traditional NFO scale with the first sub-dimension of the new NFO scale indicated that the traditional scale is slightly stronger.

Which is the preferred measure? Where they differ is their focus of attention. For the traditional NFO scale, the focus of attention is the news in general about a particular topic. For the three components of NFO introduced by Matthes, the attention is on aspects of the news that can be investigated as three specific focal points in the evaluation of relevance.

Elaborating the Concept of Relevance

Agenda setting is not a contemporary version of the massive media effects theories, such as the bullet theory or hypodermic model, that were popular in the early days of mass communication research. The media can stimulate agenda-setting effects, but the magnitude of these effects is moderated by a variety of individual differences. Among these moderators, the accumulated evidence regarding need for orientation suggests that in particular a key moderator variable is relevance. Although uncertainty also defines NFO, it plays only a secondary role of distinguishing between moderate and high NFO for persons considering a topic relevant.

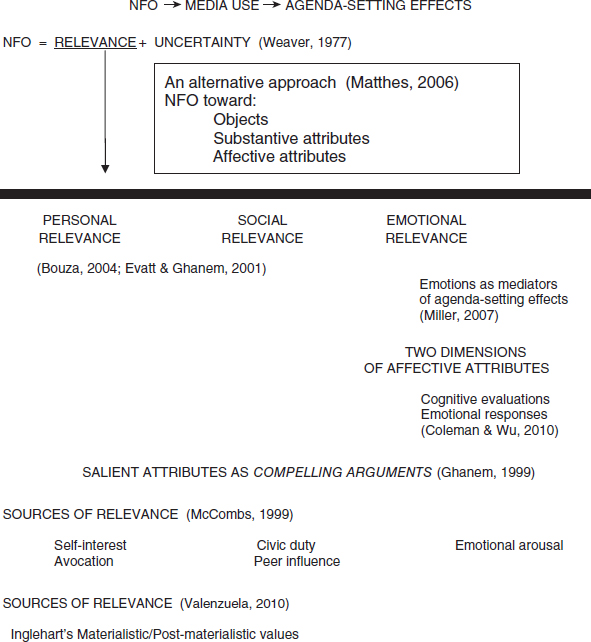

Over the years the relevance of public issues and other objects has been examined from a variety of perspectives, and closer attention to these studies in this review revealed the theoretical gestalt diagramed in Figure 1.2. Explicating the dimensions of relevance, Evatt and Ghanem's (2001) analysis of the public's response to eight different issues on a set of 13 semantic differential scales identified two substantive aspects of issue salience, social relevance and personal relevance, and an affective aspect of issue salience, emotional relevance. Bouza (2004, p. 250) made a similar theoretical distinction to identify the impact area of political communication:

Figure 1.2 A theoretical gestalt: the psychology of relevance and agenda-setting effects.

individuals maintain an important area of personal interests that is separated, to a certain degree, from what that individual considers to be public interests or everyone's interests . . . This clear distinction between an area of personal interests and another area of public interests makes the existence of an area that I will define as the impact area of political communications possible . . . because it is the area in which the individual feels a clear coincidence between the country and himself . . .

Approaching the concept of relevance from a different perspective, a pair of statewide polls in Texas explored why respondents named a particular issue in response to the widely used Gallup MIP question, “What is the most important problem facing this country today?” (McCombs, 1999). Using a set of questions developed to probe the personal resonance of an issue, analysis of these polls from 1992 and 1996 identified a stable set of five sources of issue relevance: self-interest, avocation, civic duty, peer influence, and emotional arousal. As Figure 1.2 indicates, these five motivations dovetail with Evatt and Ghanem's distinction between personal salience, social salience and emotional salience.

Focusing on emotional salience in The Political Brain, Drew Westen (2007, p. ix) declared that “the vision of mind that has captured the imagination of philosophers, cognitive scientists, economists, and political scientists since the eighteenth century – a dispassionate mind that makes decisions by weighing the evidence and reasoning to the most valid conclusions – bears no relation to how the mind and brain actually work.” And in an agenda-setting experiment, Miller (2007) found that emotional responses to the news mediated agenda-setting effects, specifically when exposure to news stories was about the issue of crime, resulted in participants feeling sad or afraid. Although these two specific emotional responses mediated the relationship between the media agenda and the public agenda, other emotional responses did not result in a greater likelihood of regarding crime as an important problem facing the nation. Altogether the experiment measured the extent to which participants felt angry, proud, hopeful, and happy as well as sad and afraid while reading news stories about crime. Only feelings of being sad or afraid mediated the agenda-setting effect. Neither a general measure of emotional arousal nor a general measure of valence created from combinations of all six emotional responses explained the link between exposure to crime news and naming crime as an important issue facing the nation. However, the creation of negative valence did result in a greater likelihood of naming crime.

These findings are an opening gambit for agenda-setting research linked with the investigation of affective intelligence, an emerging area mapping the broad role of emotions across a wide range of political behavior that complements a rational person model of human behavior with an emotional person model of human behavior (Marcus, Neuman, & MacKuen, 2000; Neuman, Marcus, Crigler, & MacKuen, 2007).

Coleman and Wu (2010) introduced a further theoretical distinction between two components of affective attributes: affect as emotion and affect as cognitive evaluations in terms of positive and negative. Details of their empirical results are presented below in the discussion of the affective impact of visual information. Here the research question is how these distinctions might clarify the concept of compelling arguments and previous research on emotional salience.

Certain characteristics of an object of attention may resonate with the public in such a way that these attributes become compelling arguments for the salience of the issue, person or topic under consideration. Ghanem (1997) found that not only did intensive crime coverage in the news generate high levels of public concern about crime as the most important problem facing the country (first-level agenda setting), but that an attribute of these crimes in the news – their psychological distance operationalized by drive-by shootings and local crime – influenced the salience of crime on the public agenda. This attribute was a compelling argument for the salience of crime as a public issue.

A dramatically different example of a compelling argument was found during the 1990 German national election, where the salience of problems in the former East Germany significantly declined among voters despite intensive news coverage (Schoenbach & Semetko, 1992). In this case, the compelling argument was the positive tone of the news coverage on the issue of German integration, an attribute that reduced the salience of the issue on the public agenda. More recent studies of compelling arguments have documented the impact of negative tone in the news on the salience of the economy on the public agenda (Sheafer, 2007); the impact of candidate attributes in the news across five US presidential elections on the public salience of those candidates (Kiousis, 2005); and during the 2000 US presidential election the impact of positive and negative attributes of issues in Kerry political ads (but not Bush ads) on the salience of these same issues on the public agenda (Golan, Kiousis, & McDaniel, et al., 2007). Although all these studies illustrate that compelling attributes on one agenda can influence object salience on another agenda, systematic theoretical mapping of which attributes function as compelling arguments – and the discrete roles of substantive and affective attributes – remains understudied.

Probing more deeply into what defines the relevance of public issues for an individual, Valenzuela (2011) found that Inglehart's (1977, 1990) concept of materialist and post-materialist values is strongly related to agenda-setting effects. Using a content analysis of major daily newspapers across Canada and survey data from a nationally representative sample interviewed during the 2006 Canadian national election, Valenzuela found that at both the aggregate and individual levels there were stronger agenda-setting effects among persons with materialist values than among those with post-materialist values. At the aggregate level, the correlation between the media agenda and the public agenda was +.55 for materialists and +.35 for post-materialists. These findings are consistent with the media's more prominent coverage of materialist issues such as the economy and crime relative to post-materialist issues such as the environment and political reform. Further analysis at the individual level used an index of post-materialist values to predict susceptibility to agenda setting (Wanta, 1997). Controlling for demographics and political involvement, people with materialist values were more susceptible to the influence of a media agenda dominated by materialist issues than people with post-materialist values.

This theoretical gestalt defined by a half dozen previously scattered studies shows considerable promise for explicating the long-standing concept of relevance in agenda-setting theory.

Knowledge Activation and Agenda Setting

Both of the knowledge activation model's core concepts, applicability and accessibility, are pertinent to agenda-setting theory. Todorov's (2000) analysis of response patterns in survey research refers to applicability as the relevance of the larger context and specifically noted “the size of accessibility effects as a function of the applicability of knowledge activated by the initial questions” (p. 430). He further noted that “applicability constrains accessibility effects – a highly accessible concept may not be applied when it doesn't share any relevant features with the stimulus” (p. 431).

In contrast, Price and Tewksbury (1997) and Kim, Scheufele, and Shanahan (2002) argued that agenda-setting effects can be explained on the basis of accessibility alone and framing effects on the basis of applicability (see Chapter 3, this volume). However, the research on need for orientation demonstrates that the salience of issues on the public agenda involves more than the accessibility of those issues as a consequence of the frequency with which they have appeared in the news. The perceived importance to an individual of an issue presented by the media is significantly moderated by that individual's perception of the issue's relevance, which is the core defining concept of need for orientation.

One of the few attempts to empirically distinguish accessibility and perceived importance is Nelson, Clawson, and Oxley's (1997) experiment comparing the effects of TV news stories that presented two different attributes of a highly publicized KKK rally, free speech versus public order. Nelson et al. concluded:

Media framing of the KKK controversy significantly affected tolerance for the group, and this effect came about primarily because the two frames stressed the relevance or importance of different values (free speech versus public order), not because the frames altered the cognitive accessibility of these values. (p. 574)

. . . Our results point to a more deliberative integration process, whereby participants consider the importance and relevance of each accessible idea. (p. 578)

Kim et al. (2002) focused specifically on the accessibility of six attributes of an urban development issue. Although the accessibility of these issue attributes increased sharply with greater exposure to the local newspaper, the resulting attribute agendas among the public did not correspond to the attribute agenda presented in the news coverage.

There was, however, no apparent correspondence of salience of attributes between the media and their audience. Among both High and Medium Exposure respondents, Increased Sales-Tax Revenues, Increased Potential for Flooding, and Increased Traffic, which were emphasized in the media, were not more salient (accessible) than other attributes. Particularly, the Increased Potential for Flooding was in fact the least salient attribute among High Exposure and Medium Exposure respondents. (Kim et al., 2002, pp. 16–17)

What emerged was a very different media effect in which the relative amount of increased accessibility for the attributes among newspaper readers paralleled the media attribute agenda. These effects are different from the attribute agenda-setting effects based on direct comparisons of the media and public attribute agendas for various issues and public figures over the years (Benton & Frazier, 1976; Dussaillant, 2005; McCombs et al., 2000; Mikami, Takeshita, Nakada, & Kawabata, 1994; Weaver et al., 1981).

Testing the hypothesis that accessibility mediates the relationship between media exposure and agenda-setting effects, Miller (2007) reported two experiments using different operational definitions of accessibility that failed to find support for the hypothesis. The relevance of an item in the news is the operative factor in setting the agenda, with considerably more modest and mixed evidence for the role of cognitive accessibility.

Consequences for Attitudes and Opinions

Contemporary research is mapping the consequences of both first and second-level agenda-setting effects for attitudes and opinions, both the traditional focus in communication research on the direction of opinion – whether it is positive or negative – as well as the strength of opinion. The latter begins with the question of whether people have an opinion at all and subsequently considers the intensity of that opinion regardless of its direction.

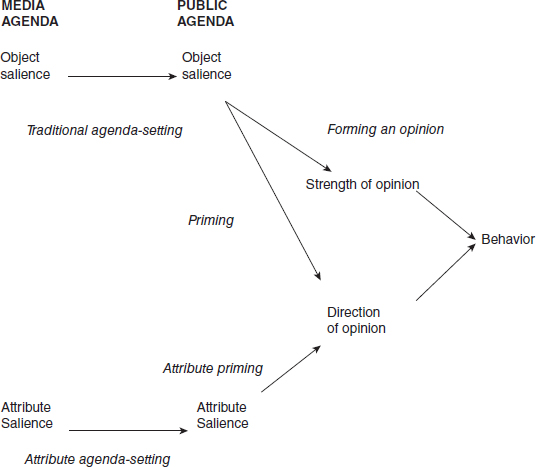

Among the consequences of agenda-setting effects for the direction of opinion, priming is the most widely investigated. Priming is the influence of the news media on the criteria that people use to evaluate political figures and government policies. The agenda-setting effects of news coverage frequently result in the enhanced salience of an issue among the public, and this issue in turn becomes the criterion for evaluating a political figure or government policy. In other words, priming is an extension of the agenda-setting process (Iyengar & Simon, 1993; Scheufele, 2000).

In the classic laboratory experiments conducted by Iyengar and Kinder (1987), issues that received extensive TV news coverage were more salient (agenda-setting effects) and were more likely to influence evaluations of the president's performance (priming effects) among participants exposed to this news than among a control group. Priming effects also have been found in field studies. Heavy news coverage of the Iran-Contra scandal shortly after the 1986 election significantly influenced respondents' opinions about Ronald Reagan's performance as president. The weight of assistance to the Contras in evaluations of the president increased substantially after revelation of the scandal (Krosnick & Kinder, 1990). Research on priming beyond the US political context has demonstrated similar results. News coverage of political reform proposals announced by the last British governor of Hong Kong significantly influenced the weight that the public assigned to these proposals in their evaluation of the governor's performance (Willnat & Zhu, 1996). News coverage of various issues during the 1986 German election also primed preferences for the two major political parties (Brosius & Kepplinger, 1992).

Another source of influence on the direction of opinion is attribute priming. As illustrated in Figure 1.3, attribute priming is a consequence of attribute agenda-setting effects, a process elaborating the broader concept of attitude and opinion change in which it is the increased salience among the public of specific attributes emphasized in news coverage that influences the weights people assign to those attributes in their evaluations of attitude objects.

Figure 1.3 Consequences of agenda-setting effects for opinions and behavior. Reprinted from M. McCombs (2004). Setting the agenda. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

This process of attribute priming frequently is a consequence of the affective tone of particularly salient attributes; that is, the degree to which salient attributes are perceived as positive or negative by the public. Sheafer (2007) refers to this influence as affective attribute priming and found significant evidence for this consequence of attribute agenda setting in his study of five Israeli elections. The more negative the media coverage of the economy, the lower were the evaluations of the general performance of the incumbent political party. Media coverage not only primed the economy as a criterion for judging the performance of the party in power, the affective tone of that coverage influenced the direction of the evaluations.

A study of state and federal elections in Texas combined both substantive and affective dimensions to examine the effects of attribute priming on people's opinions of the candidates for governor and US senator (Kim & McCombs, 2007). Significant relationships were found between the attribute agenda-setting effects of the news media and people's opinions of these four candidates. Additional analyses found that a greater number of the attributes describing the candidates' qualifications and character predicted individuals' opinions toward the candidates for heavy readers than for light readers.

Other evidence of a link between the affective attribute agenda and the direction of opinions was found in a comparison of Spanish citizens' ratings of six major political figures on an attitude scale with their descriptions of these men in response to an open-ended question used to elicit their attribute agendas (Lopez-Escobar, McCombs, & Tolsa, 2007). For these six public figures, the correlations between citizens' ratings and the overall tone of their affective attribute agenda ranged from +.78 to +.97. Low ratings were coupled with very negative descriptions, high ratings with very positive descriptions.

The consequences of agenda-setting effects also have been investigated for opinion formation and the strength of attitudes and opinions. Kiousis and McCombs (2004) found that the salience of 11 public figures in the news during the 1996 US presidential election was strongly correlated with the proportion of the public having an opinion about these persons, in particular, the strength of those opinions measured by both dispersion (holding a non-neutral opinion) and polarization (holding an extreme opinion). For dispersion, the median correlation was +.81; for polarization, +.70

Evidence for a link between the public salience of issues and opinion strength also was documented by Rossler and Schenk (2000). The salience of two issues, German reunification and East German migrants, significantly predicted the strength of opinion on these two issues.

In accordance with the traditional sequence in hierarchy of effects models (McGuire, 1989), the prevailing view is that media salience influences public salience (an agenda-setting effect), which in turn affects the strength of opinion on the issue. However, Kiousis and McCombs (2004) found evidence for a transposed sequence of effects. Both opinion dispersion (holding a non-neutral attitude) and opinion polarization (holding an extreme attitude) mediated the relationship between the media salience and public salience of major public figures. In other words, media salience influenced having an opinion about a person, which in turn affected the public salience of that person. Though Kiousis and McCombs raised an intriguing question about the order of the relationship between issue salience and attitude strength, nevertheless, their study provided strong evidence for a link between agenda setting and opinion formation.

For the budget deficit issue, Weaver (1991) documented significant relationships between issue salience and both opinion strength and the direction of opinion. As the salience of the deficit issue increased, opinion on the issue became stronger. Weaver (1991, p. 65) also noted the effects on the direction of opinion: “These findings tend to support Katz's (1980) conclusion that ‘as a latent consequence of telling us what to think about, the agenda-setting effect can sometimes influence what we think’. . .”

Affective Impact of Visual Information

Although the television agenda, both at the first and second levels of agenda setting, is included in dozens of studies, nearly all of the television data reflects the text messages of TV news and political advertising. However, television is preeminently a visual medium of communication, and the lack of research examining its visual component has been a significant gap in our understanding of the agenda-setting role of the media.

Expanding second-level agenda setting to include the affective agenda of television news in its visual portrayals of presidential candidates, Coleman and Banning (2006) examined the national television news coverage of George Bush and Al Gore during the 2000 US presidential campaign. Their content analysis of the two candidates' nonverbal behavior – facial expressions, posture, and gestures – found more shots showing positive behavior by Gore than by Bush and more shots showing negative behavior by Bush than by Gore.

To determine whether these television images are related to the public's affective impressions of Bush and Gore, Coleman and Banning conducted a secondary analysis of the 2000 National Election Studies. One set of NES questions for each candidate asked if he had ever made the respondent feel “angry,” “hopeful,” “afraid,” and “proud.” Another set of questions asked respondents to what extent seven words and phrases described Bush and Gore. Two of these referred to negative character traits – “dishonest” and “out of touch with ordinary people”, while five referred to positive character traits – “moral,” “really cares about people like you,” “knowledgeable,” “provides strong leadership,” and “intelligent.” Scores on these questions were summed to form a positive and a negative affective attribute index for each candidate.

Comparisons of the positive and negative media agenda of attributes with the public's positive and negative agenda of attributes found modest evidence for the impact of visual messages. For Bush, there were significant correlations between the media and the public for both the positive and negative attribute agendas (+.13 for each). For Gore there was a significant correlation between the media and public only for the positive attribute agenda (+.20). Coleman and Banning (p. 321) note, “While the effect of nonverbal cues may be less than the effects reported for some verbal cues, the effect is nevertheless significant. . . . Visuals can play an important albeit modest role in facilitating impression formation in the political process.”

Extending this analysis of affective agenda-setting effects from visuals, Coleman and Wu (2010) introduced the theoretical distinction noted earlier between affect as emotion and affect as cognitive evaluations in terms of positive and negative. No significant correlations were found between their measures of nonverbal behavior by Bush and Gore in the TV news shots with either the public's cognitive evaluations of the candidates' traits or the public's positive emotional responses to the candidates. Significant relationships were found between the content of the TV visuals and negative emotional responses (+.10 for Bush and +.12 for Kerry).

Political and Civic Participation

Beyond their impact on attitudes and opinions, agenda-setting effects have consequences for a wide scope of political and civic behavior. Discussion of politics, voting on election day, and donating money to political causes as well as more diffuse aspects of civic participation, such as membership in civic groups and community involvement, are linked to agenda-setting effects (Moon, 2008). There are consequences of first-level agenda-setting effects on issues from exposure to newspapers and television for both political participation and civic participation, consequences that are both direct as well as mediated by opinion strength. For second-level agenda-setting effects on the images of candidates, Moon found consequences for political participation from exposure to newspapers and television. The impact of agenda-setting effects on political participation was both direct as well as mediated by opinion strength. Exposure to the news and the resulting agenda-setting effects facilitate a wide range of political and civic participation.

Conclusion

Civic osmosis, the acquisition of information about public affairs often with little effort or close attention, results from the ubiquity and redundancy of the mass media. Among the significant by-products of these repetitive messages in the media are basic agenda-setting effects and attribute agenda-setting effects. However, this media influence on the foundations of public opinion is tempered by individual differences among members of the public in the perceived relevance of these messages. A major contribution of this chapter is a theoretical gestalt elaborating the concept of relevance, which is the major theoretical component of need for orientation. This gestalt links a set of three perspectives on relevance – personal, social, and emotional – with the idea of compelling arguments and with individual attitudes defined by Inglehart's materialistic/post-materialistic values. This gestalt also further elaborates the emotional aspects of agenda setting. Beyond explicating the moderating and mediating variables in the psychology of agenda setting, this review also suggests new avenues of research into the consequences of agenda-setting effects for attitudes, opinions, and behavior. All of this will be productive for mapping agenda-setting effects in the expanding media landscape, a setting in which the broad effects of the traditional media and their new media counterparts are likely to co-exist with the tightly focused effects of niche media serving narrow and highly selective personal interests.

Agenda setting continues to offer an expanding array of new and theoretically important questions to be explored in all five areas of the theory. In the words of the famous fictional detective, Sherlock Holmes, “Come, Watson, come. The game is afoot.”

REFERENCES

Acar, A. (2007). Testing the effects of incidental advertising exposure in online gaming environments. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 8.

Baum, M. A. (2002). Sex, lies, and war: How soft news brings foreign policy to the inattentive public. American Political Science Review, 96, 91–109.

Baum, M. A. (2003). Soft news goes to war: Public opinion and American foreign policy in the new media age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Beales, H., Mazis, M. B., Salop, S. C., & Staelin, R. (1981). Consumer search and public policy Journal of Consumer Research, 8, 11–22.

Benton, M., & Frazier, P. J. (1976). The agenda setting function of the mass media at three levels of “information holding.” Communication Research, 3, 261–274.

Bettman, J. R. (1979). An information processing theory of consumer choice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bouza, F. (2004). The impact area of political communication: Citizenship faced with public discourse. International Review of Sociology, 14, 245–259.

Brosius, H.-B., & Kepplinger, H. M. (1992). Beyond agenda-setting: The influence of partisanship and television reporting on the electorate's voting intentions. Journalism Quarterly, 69, 893–901.

Chernov, G., Valenzuela, S., & McCombs, M. (2009, August). A comparison of two perspectives on the concept of need for orientation in agenda-setting theory. Paper presented at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication annual conference, Boston, MA.

Coleman, R., & Banning, S. (2006). Network TV news' affective framing of the presidential candidates. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 83, 313–328.

Coleman, R., & McCombs, M. (2007). The young and agenda-less? Age-related differences in agenda-setting on the youngest generation, baby boomers, and the civic generation. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 84, 299–311.

Coleman, R., & Wu, H. D. (2010). Proposing emotion as a dimension of affective agenda-setting: Separating affect into two components and comparing their second-level effects. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 87, 315–327.

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of democracy. New York, NY: Harper.

Dussaillant, P. (2005). Medios y elecciones: La elección presidencial de 1999. Santiago, Chile: Centro de Estudios Bicentenario/CIMAS.

Eaton, Jr., H. (1989). Agenda-setting with bi-weekly data on content of three national media. Journalism Quarterly, 66, 942–959.

Evatt, D., & Ghanem, S. I. (2001, September). Building a scale to measure salience. Paper presented at the World Association of Public Opinion Research annual conference, Rome, Italy.

Fortunato, J. A. (2001). The ultimate assist: The relationship and broadcasting strategies of the NBA and television networks. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Frensch, P. A. (1998). One concept, multiple meanings. In M. A. Stadler & P. A. Frensch (Eds.), Handbook of implicit learning (pp. 47–104). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ghanem, S. (1997). Filling in the tapestry: The second level of agenda setting. In M. E. McCombs, D. L. Shaw, & D. H. Weaver (Eds.) Communication and democracy: Exploring the intellectual frontiers in agenda-setting theory (pp. 309–330). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Golan, G.J., Kiousis, S. K., & McDaniel, M. L. (2007). Second-level agenda setting and political advertising: Investigating the transfer of issue and attribute saliency during the 2004 US presidential election. Journalism Studies, 8. 432–443.

Hellinger, M., & Rashi, T. (2009). The Jewish custom of delaying communal prayer: A view from communication theory. Review of Rabbinic Judaism, 12, 189–203.

Higgins, E. T. (1996). Knowledge activation: Accessibility, applicability, and salience. In E. T. Higgins & A. W. Kruglanski (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (pp. 133–168). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Inglehart, R. (1977). The silent revolution: Changing values and political styles in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Iyengar, S., & Simon, A. (1993). News coverage of the Gulf crisis and public opinion: A study of agenda-setting, priming, and framing. Communication Research, 20, 365–383.

Janiszewski, C. (1993). Preattentive mere exposure effects. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 376–392.

Jenkins, J. G. (1933). Instruction as a factor in “incidental” learning. American Journal of Psychology, 45, 471–477.

Katz, E. (1980). On conceptualizing media effects. Studies in Communication, 1, 119–141.

Kim, K., & McCombs, M. (2007). News story descriptions and the public's opinions of political candidates. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 84, 299–314.

Kim, S. H., Scheufele, D. A., & Shanahan, J. (2002). Think about it this way: Attribute agenda-setting function of the press and the public's evaluation of a local issue. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 79, 7–25.

Kiousis, S. (2005). Compelling arguments and attitude strength: Exploring the impact of second-level agenda setting on public opinion of presidential candidate images. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 10(2), 3–27.

Kiousis, S., & McCombs, M. E. (2004). Agenda-setting effects and attitude strength: Political figures during the 1996 presidential election. Communication Research, 31, 36–57.

Krosnick, J. A., & Kinder, D. R. (1990). Altering the foundations of support for the president through priming. American Political Science Review, 84, 497–512.

Krugman, H. E. (1965). The impact of television advertising: Learning without involvement. Public Opinion Quarterly, 29, 349–356.

Lazarsfeld, P., Berelson, B., & Gaudet, H. (1944). The people's choice. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Lee, J. K. (2009). Incidental exposure to news: Limiting fragmentation in the new media environment. (Unpublished dissertation.) University of Texas at Austin.

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Lopez-Escobar, E., McCombs, M., & Tolsa, A. (2007, March). Measuring the public images of political leaders: A methodological contribution of agenda-setting theory. Paper presented to the Congreso do Investigatión en Comunicación Politica, Madrid, Spain.

Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., & MacKuen, M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgment. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Matthes, J. (2006). The need for orientation towards news media: Revising and validating a classic concept. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18, 422–444.

Matthes, J. (2008). Need for orientation as a predictor of agenda-setting effects: Causal evidence from a two-wave panel study. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 20, 440–453.

McCombs, M. (1999). Personal involvement with issues on the public agenda. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 11, 152–168.

McCombs, M. E. (2004). Setting the agenda: The mass media and public opinion. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

McCombs, M. E., Lopez-Escobar, E., & Llamas, J. P. (2000). Setting the agenda of attributes in the 1996 Spanish general election. Journal of Communication, 50, 77–92.

McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36, 176–187.

McGuire, W. J. (1989). Theoretical foundations of campaigns. In R. E. Rice & C. K. Atkins (Eds.), Public communication campaigns (2nd ed., pp. 43–65). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

McLaughlin, B. (1965). ‘Intentional’ and ‘incidental’ learning in human subjects: The role of instructions to learn and motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 359–376.

Meijer, M., & Kleinnijenhuis, J. (2006). Issue news and corporate reputation: Applying the theories of agenda setting and issue ownership in the field of business communication. Journal of Communication, 56, 543–559.

Mikami, S., Takeshita, T., Nakada, M., & Kawabata, M. (1994, July). The media coverage and public awareness of environmental issues in Japan. Paper presented at the International Association for Mass Communication Research. Seoul, Korea.

Miller, J. M. (2007). Examining the mediators of agenda setting: A new experimental paradigm reveals the role of emotions. Political Psychology, 28, 689–717.

Moon, S. J. (2008). Agenda-setting effects as a mediator of media use and civic engagement: From what the public thinks about to what the public does. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation.) University of Texas at Austin.

Nelson, T. E., Clawson, R. A., & Oxley, Z. M. (1997). Media framing of a civil liberties conflict and its effect on tolerance. American Political Science Review, 91, 567–583.

Neuman, W. R., Just, M. R., & Crigler, A. N. (1992). Common knowledge: News and the construction of political meaning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Neuman, W.R., Marcus, G.E., Crigler, A.N., & MacKuen, M. (2007). The affect effect: Dynamics of emotion in political thinking and behavior. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Popkin, S. L. (1994). The reasoning voter: Communication and persuasion in presidential campaigns (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Posner, M. I. (1973). Cognition: An introduction. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1997) News values and public opinion: A theoretical account of media priming and framing. In G. A. Barnett & F. J. Boster (Eds.), Progress in communication sciences (pp. 173–212). Greenwich, CT: Ablex.

Robertson, T. S. (1976). Low-commitment consumer behavior. Journal of Advertising Research, 16, 19–24.

Rodriguez, R. (2004). Teoría de la agenda-setting: Aplicación a la enseñanza universitaria. Alicante, Spain: Observatorio Europeo de Tendencias Sociales.

Rossler, P., & Schenk, M. (2000). Cognitive bonding and the German reunification: Agenda setting and persuasion effects of mass media. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 12, 29–47.

Scheufele, D. A. (2000). Agenda-setting, priming, and framing revisited: Another look at cognitive effects of political communication. Mass Communication and Society, 3, 297–316.

Schoenbach, K., & Semetko, H. (1992). Agenda setting, agenda reinforcing or agenda deflating? A study of the 1990 German national election. Journalism Quarterly, 60, 226–32.

Shaw, D. L., & McCombs, M. E. (1977). The emergence of American political issues: The agenda-setting function of the press. St. Paul, MN: West.

Sheafer, T. (2007). How to evaluate it: The role of story-evaluative tone in agenda setting and priming. Journal of Communication, 57, 21–39.

Stromback, J., & Kiousis, S. (2010). A new look at agenda-setting effects – Comparing the predictive power of overall political news consumption and specific media consumption across different media channels and media types. Journal of Communication, 60, 271–292.

Takeshita, T. (1993). Agenda-setting effects of the press in a Japanese local election. Studies of Broadcasting, 29, 193–216.

Todorov, A. (2000). The accessibility and applicability of knowledge: Predicting context effects in national surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64, 429–451.

Valenzuela, S. (2011). Materialism, postmaterialism and agenda-setting effects: The values–issues consistency hypothesis. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 23, 437–463.

Wanta, W. (1997). The public and the national agenda: How people learn about important issues. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wanta, W., & Ghanem, S. I. (2000). Effects of agenda-setting. In J. Bryant & R. Carveth (Eds.), Meta-analysis of media effects (pp. 37–52). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Weaver, D. H. (1977). Political issues and voter need for orientation. In D. L. Shaw & M. E. McCombs (Eds.), The emergence of American political issues (pp. 107–119). St. Paul, MN: West.

Weaver, D. H. (1991). Issue salience and public opinion: Are there consequences of agenda-setting? International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 3, 53–68.

Weaver, D. H., Graber, D. A., McCombs, M. E., & Eyal, C. H. (1981). Media agenda-setting in a presidential election: Issues, images, and interest. New York, NY: Praeger.

Westen, D. (2007). The political brain: The role of emotions in deciding the fate of the nation. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

Willnat, L., & Zhu, J.-H. (1996). Newspaper coverage and public opinion in Hong Kong: A time-series analysis of media priming. Political Communication, 13, 231–246.

Zukin, C., & Snyder, R. (1984). Passive learning: When the media environment is the message. Public Opinion Quarterly, 48, 629–638.

FURTHER READING

Balmas, M., & Sheafer, T. (2010). Candidate image in election campaigns: Attribute agenda-setting, affective priming and voting intentions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 22, 204–229.

Carroll, C. (2010). Corporate reputation and the news media: Agenda-setting within business news coverage in developed, emerging, and frontier markets. New York, NY: Routledge.

Dearing, J., & Rogers, E. (1996). Agenda setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Gross, K., & Aday, S. (2003). The scary world in your living room and neighborhood: Using local broadcast news, neighborhood crime rates, and personal experience to test agenda setting and cultivation. Journal of Communication, 53(3), 411–426.

Shaw, D., & Martin, S. (1992). The function of mass media agenda setting. Journalism Quarterly, 69, 902–920.

Son, Y. J., & Weaver, D. H. (2006). Another look at what moves public opinion: Media agenda setting and polls in the 2000 US election. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(2): 174–197.

Soroka, S. (2002). Agenda-setting dynamics in Canada. Vancouver, BC, Canada: UBC Press.

Tai, Z. (2009). The structure of knowledge and dynamics of scholarly communication in agenda setting research, 1996–2005. Journal of Communication, 59, 481–513.

Takeshita, T. (2006). Current critical problems in agenda-setting research. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(3), 275–296.

Wu, H. D., & Coleman, R. (2009). Advancing agenda setting theory: The comparative strength and new contingent conditions of the two levels of agenda setting effects. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 86, 775–789.