2

And Now a Click from Our Sponsors

Changes in Children's Advertising in the United States

ABSTRACT

Many children worldwide spend a considerable amount of time with media. However, children's exposure to advertising may differ as a reflection of different public policies enforced around the world. Many policies worldwide place limits on the amount of advertising permitted, yet concerns rise about the nature of the messages (whether few or many) that children encounter. Therefore, this literature review will examine advertising messages that appear in children's media environments, focusing on television content and then exploring advertising in new media, specifically online advertising. Content analyses of electronic advertising reflect the interplay between public policy, industry self-regulation, and marketplace forces. As such, the United States provides an example of how these three forces operate together and is the focus of this review.

Many children growing up in the world today spend a considerable amount of time in front of the television screen. For example, recent research indicates that US children ages 8–18 spend a little over 7½ hours with media per day, and over half of that time (4½ hours) is spent with TV content (Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). Irish children ages 4–14 spent an average of over 2½ hours per day watching television between 2000 and 2002 (Broadcasting Commission of Ireland [BCI], 2003). Similarly, Australian children ages 0–14 years watched an average of over 2½ hours per day of free-to-air broadcasts in 2001 but decreased to just over 2 hours per day by 2006 (Australian Communications and Media Authority [ACMA], 2007). Indeed, daily viewing time of children in Poland, Spain, the United Kingdom, France, Australia, Sweden, and Germany increased in 2010 compared to 2009 (Szybist, 2011). Considering the amount of television children watch, their exposure to television advertising is potentially quite high. Research in the United States suggests that young children ages 2–7 years see an average of 13,904 television ads per year, whereas children ages 8–12 years see 30,155 ads, and children ages 13–17 years see 28,656 ads (Gantz, Schwartz, Angelini, & Rideout, 2007). However, children's exposure to advertising may be quite different around the world as a result of public policies regulating children's advertising.

A full spectrum of regulatory policies of children's advertising can be found around the world. Some countries such as Sweden and Norway ban all television advertising directed to children under 12 years of age (Gunter, Oates, & Blades, 2005). Other countries restrict advertising to younger children only or during and adjacent to children's programs. Australia does not permit advertising during programs targeted to preschoolers (ACMA, 2005). In the Flemish area of Belgium, no advertising is permitted within 5 minutes before or after programs for children under the age of 12, and Denmark prohibits advertising breaks during programs throughout the broadcast day (Quinn, 2002). By contrast, other countries permit advertising to children, but the parameters for permitted children's advertising in various countries differ as well as the authority of the government in relation to self-regulatory agencies. For example, in the United States, governmental regulation permits no more than 12 minutes of advertising per hour on weekdays and 10.5 minutes per hour on weekends at the macro level (Kunkel & Wilcox, 2001). However, content guidelines are not federally mandated. The self-regulatory agency of the Children's Advertising Review Unit (CARU) offers guidelines but relies on the “good-faith cooperation of advertisers” to follow their suggestions (Kunkel & Gantz, 1993, p. 151).

While many policies worldwide place limits on the amount of advertising permitted, concerns rise about the nature of the messages (whether few or many) that children encounter. Therefore, this literature review will examine advertising messages that appear in the children's media environment, focusing on television content and then exploring advertising in new media. The review will focus on quantitative content analysis research that takes a broad-based look at the advertising on children's television. Research that focuses on one specific category of television advertising (such as food advertising) or one key element of advertising depictions (such as character gender) is excluded from this current review. Moreover, this review will focus on advertising practices in the United States as an example of the interplay between self-regulatory guidelines, governmental regulation, and marketplace forces.

Television Marketplace and Policy Changes in the United States

Trends in advertising content on television are particularly interesting given media and policy changes in the United States over the years. Three notable changes occurred in children's media during the 1980s. First, a “licensing frenzy” (Bryant, 2007, p. 19) flourished as toy manufacturers, content creators, and broadcasters formed relationships that blurred the lines between content and marketing, creating branded play both on and off the screen. Second, cable began to penetrate more and more homes in the United States. Along with the rise of cable came the launch of two channels dedicated entirely to the child audience, Nickelodeon and the Disney channel, in the early 1980s. These channels provide a specialized outlet for advertisers to reach their target audience. Finally, videogames began to become popular in the home, and with portable games available by the end of the 1980s, the future of advertising and children's media would forever be changed.

Marketplace changes reflected policy changes in children's media regulation. Alexander and Hoerrner (2007) refer to the 1980s as the “deregulation decade” in which “the marketplace was supposed to separate quality programs from junk, and it was supposed to punish advertisers who unfairly target children with deceptive messages” (p. 36). The Federal Communication Commission (FCC) determined that if appropriate alternative programming existed for children in the community, then the broadcaster was no longer responsible to serve the needs of the child audience (Kunkel & Wilcox, 2001). The result of this deregulatory position from the FCC was reflected in the abundance of program-length commercials where the lines of marketing and content are blurred through toy, product, and content tie-ins as described above. This blurring had further implications for the FCC's second major type of policy known as the “separation principle” in which stations are mandated to maintain a clear distinction between program and commercial content. During this era of deregulation, the FCC relaxed its position on program-length commercials originally defined as programs associated with products, hence the prevalence of these types of programs in the 1980s. Faced with pressure from Congress to re-regulate the industry, the FCC redefined program-length commercials to resemble the definition of host-selling such that traditional advertising engaging the use of television characters to promote a product could not be placed adjacent to or within a children's program involving those characters.

Another programming policy change that had implications on advertising regulation was the adoption of the Children's Television Act (CTA) of 1990, which marked the end of the deregulatory era and the beginning of the “decade of reckoning” (Alexander & Hoerrner, 2007, p. 37). One requirement of the CTA of 1990 was the restriction of the amount of advertising permitted during children's television programming to no more than 12 minutes per hour on weekdays and 10.5 minutes per hour on weekends. The regulations went into effect in fall of 1992, and a study of seven markets indicated a reduction of one 30-second advertisement on average between 1991 and 1992 (Snyder, 1995). However, by 1994, advertising had returned to pre-Act rates (Snyder, 1995) similar to rates documented in 1993 by Byrd-Bredbenner (2002). By 1999, the networks were back in compliance (Byrd-Bredbenner, 2002) and appeared to have remained in compliance in 2005 when all commercial broadcast stations reported an average of 7.95 minutes per hour of advertising content during children's programs (Gantz et al., 2007).

Moreover, as digital television came into existence, discussions opened concerning broadcasters' obligations to serve the child audience in the new digital age in respect to advertising and program content material both online and on digital television. In the fall of 2000, the Federal Communication Commission released a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (FCC-00-344) to seek comments on a variety of issues relating to digital television and the child audience (FCC, 2000). After reviewing the comments, the FCC released a Report and Order (FCC-04-221) with new proposed rulemaking (FCC, 2004). In respect to advertising and children, the Report and Order prohibited the appearance of websites in programming content that links to commercial material, redefined commercial material to include promotions for non-educational programming, and changed the definition of host-selling. On February 9, 2006, child advocate organizations such as Children Now and various representatives from the industry such as Viacom, The Walt Disney Company, and Fox Entertainment Group submitted a Joint Proposal (FCC-06-33A2) to the FCC which suggested the following changes in relation to advertising content: (1) the Website Rule; (2) the Host-Selling Rule; and (3) the Promotions Rule (FCC, 2006).

The Website Rule

The FCC proposed that any display of websites during programming directed to children ages 12 and under be permitted as long as they meet the following criteria: (1) the website provides substantial program-related or other educational material, (2) the website is not primarily intended for commercial purposes, (3) the website's home page and other pages clearly separate and label commercial from noncommercial content, and (4) the website is not used for e-commerce or other commercial purposes (FCC, 2004). Any websites that do not meet this four-part test would be counted toward the total minutes of advertising time permitted by the Children's Television Act of 1990 (no more than 12 minutes per hour weekdays and no more than 10.5 minutes per hour on weekends). The Joint Proposal suggested that display of websites only count toward the total time allotment if the display is during programming material or during a promotion, and that the promotion needs to be clearly separated from programming material (FCC, 2006).

The Host-Selling Rule

The FCC proposed a ban on the display of websites during children's programming or during commercial material that use characters from the program to sell products or services (FCC, 2004). The Joint Proposal suggested website addresses displayed during or adjacent to a program should not contain products that feature characters from that program or characters appearing in that program that are actively used to sell the products. However, this rule should not apply to third-party links from a company's web page, on-air third-party advertisements with websites, or pages that are primarily dedicated to multiple programs or multiple characters (FCC, 2006).

The Promotions Rule

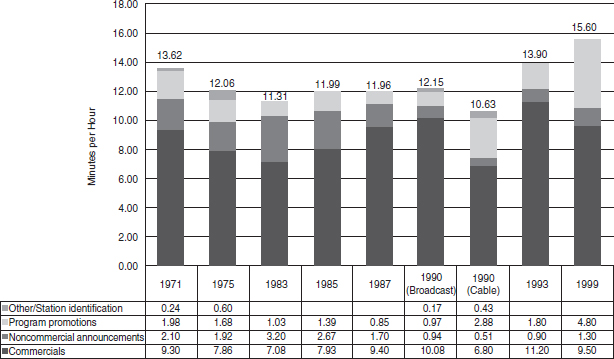

According to the FCC, commercial matter is redefined to include promotions of non-educational or informative television programs or video programming services (FCC, 2004). The Joint Proposal suggested that promotions for children's or other age-appropriate programming appearing on the same channel or promotions for children's E/I programming on any channel should not be included as commercial matter (FCC, 2006). Until 1999, time for program promotions hovered between one to two minutes per hour (Barcus, 1975; Condry, Bence, & Schiebe, 1988; Kunkel & Gantz, 1992). However, in 1999, the time for program promotions jumped dramatically to almost five minutes per hour (Byrd-Bredbenner, 2002).

Decision

On September 26, 2006, the FCC approved a Second Order on Reconsideration and Second Report and Order based on revisions filed in response to the 2004 Order and the Joint Proposal. As such, the FCC adopted the changes suggested by the Joint Proposal in order to make a clear separation of commercial websites from programming content. In regard to the FCC's proposed host-selling rule, the FCC permits the sale of merchandise featuring a program-related character in parts of the website that are clearly and sufficiently separated from the program itself. Finally, the FCC accepted the suggestion made in the Joint Proposal and refrained from considering promotions as “commercial matter.”

Historical Comparisons of Non-Program Content in Children's Television in the United States

Despite concerns voiced about the effects of advertising on children and youth, few comprehensive content analyses that cover all forms of non-program content during children's programs have been conducted. In the early 1970s, F. Earle Barcus documented the state of advertising and non-program content during children's television programming. His work set a precedent for examination of non-program content and has been replicated and applied to television advertising from the 1950s (Alexander, Benjamin, Hoerrner, & Roe, 1999), 1980s (Condry et al., 1988), 1990s (Byrd-Bredbenner, 2002; Kunkel & Gantz, 1992), and in the new millennium (Gantz et al., 2007).

Given this similarity in coding schemes, comparisons can be made across time with a few exceptions. First, to date, no published studies have been discovered for television advertising on children's programs in the 1960s. Therefore, for this literature review, the 1960s will be omitted from analysis. Second, Gantz and his colleagues (2007) employed a different strategy for sampling of programs. They submit that since children often watch programming that is intended for a broader audience, it is necessary to examine the advertising content in programs children actually view rather than limiting the analyses to just programs produced for children. All of the other studies included children's programming only. Therefore, comparisons are limited with this most recent study (Gantz et al., 2007). Third, Kunkel and Gantz (1992) made distinctions between cable and broadcast networks in their analyses. When appropriate, comparisons will be made with broadcast networks only across time, but the results regarding cable in 1990 will be provided.

Amount of Non-Program Content in the United States

Barcus (1979) identified four different kinds of non-program content including: (1) commercial product announcements, (2) program promotional announcements, (3) noncommercial announcements, and (4) other/station identification. The commercial product announcements were advertisements for products and included such codes as the name of the manufacturer, the product advertised, product claims, and marketing tactics. The program promotions included announcements for upcoming television programs. The noncommercial announcements consisted of public service announcements, and the last category captured other announcements including station identification messages. In the 1980s, Condry and his colleagues (1988) separated the noncommercial announcements into two categories: (1) public services announcements (PSAs) and (2) educational drop-ins (drop-ins). Both of these categories involved educational messages about health, safety, nutrition, and other information. However, a PSA was created by a nonprofit organization whereas a drop-in was produced or co-produced by a network. Furthermore, Condry and his colleagues combined program promotions with station identifications under the category of promos. Byrd-Bredbenner (2002) followed the same categorization as Condry and his colleagues (1988), whereas Kunkel and Gantz (1992) separated the station identifications from other types of messages. For comparison with Barcus, the PSAs and drop-ins were combined as well as station identification and the “other” category.

Figure 2.1 Non-program content type by year.

Changes can be seen across the years in both advertising and noncommercial announcements (see Figure 2.1). For a decade between 1975 and 1985, commercial advertising remained at its lowest (between 7 and 8 minutes) on broadcast networks. Beginning in 1985, the amount of advertising content rose, reaching a peak in 1993. By the end of the almost 30-year span, the amount of advertising returned to near original rates at just under 10 minutes per hour.

While advertising content seemed to rise, less time was spent on noncommercial messages. The amount of time dedicated to noncommercial content reached a peak in 1983 at 3.20 minutes per hour. After 1983, noncommercial content decreased to reach its all time low in 1993. In 1999, an increase was noted. Indeed, between 1983 and 1993, as the amount of time for commercial messages continued to rise, the amount of time dedicated to noncommercial content waned. As a result, there became a growing emphasis on advertising rather than on the noncommercial content such as educational drop-ins and public service announcements.

Moreover, the average length of a commercial on the networks has changed dramatically since 1950, but held relatively stable from the 1970s to the 1980s. Standardization of programming and advertising length was not a common practice in the 1950s. As a result, the length of advertisements in the 1950s ranged from as short as 11 seconds to as long as 3½ minutes; however, the average length of advertisements in the 1950s was a little over 1 minute (Alexander et al., 1999). Over time, advertisements begin to decrease in length. Between 1971 and 1975, the average commercial length declined from .56 minutes to .50 minutes (Barcus, 1979), the equivalent of the new 30-second spot.

Indeed, in the 1970s, the vast majority of the advertisements (92%) were 30-second spots (Atkin & Heald, 1977). The average commercial length continued to shrink in the 1980s. The average commercial length began at 30.90 seconds in 1983 and gradually decreased to 29.63 in 1984 and to 29.31 seconds in 1987 (Condry et al., 1988). Kunkel (2001) suggests that advertising spots may even be as short as 15 seconds in the 1990s, although no studies conducted in the 1990s or the 2000s report the average commercial length.

Products Advertised in the United States

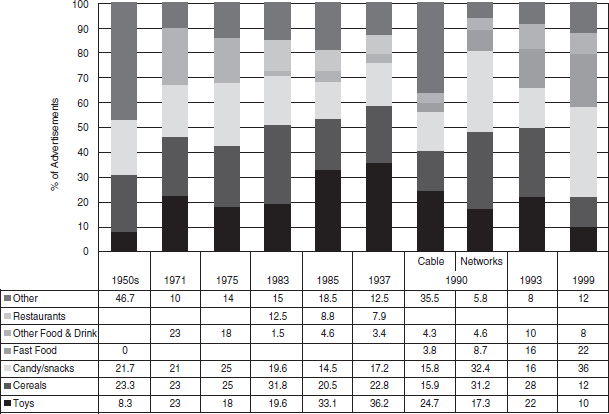

While seasonal differences were observed in the frequency of toy commercials (Barcus, 1980; Condry et al., 1988), research in the 1970s indicated that four product categories – toys, cereals, candies, and fast food restaurants – made up the lion's share of product types advertised to children, accounting for 80% of all ads (Barcus, 1980). This was a dramatic change from advertising in the 1950s where only 44% of commercials advertised products in these categories (Alexander et al., 1999) (see Figure 2.2). Products such as appliances, dog food, and food staples such as milk and peanut butter were more common at that time, which may be a reflection of the novelty of television such that even adults would watch children's programs (Alexander et al., 1999). Studies conducted in the 1980s and early 1990s indicate that the four product categories from the 1970s still dominated the field, but fluctuation in the distribution of these categories changed over time. By 1975, cereals (25%) and sweets (25%) accounted for half of the products advertised (Barcus, 1979). However, in the 1980s, advertisements for candies (17.2%) and cereals (22.8%) declined while toy commercials (36.2%) increased dramatically (Condry et al., 1988).

Figure 2.2 Type of products advertised by year.

Ads for “other” products – including such things as hygiene, clothing, leisure activities, recreation parks, recorded music, and entertainment – have also experienced fluctuation. Ads for “other” products grew in the 1980s, reaching a peak in 1985 at 18.5% of all advertisements (see Figure 2.2). However, these fluctuations were noted on broadcast networks only. In 1990, a comparison could be made between types of products advertised during children's programs on cable networks and on broadcast networks. Interestingly, advertisements for “other” products accounted for a little over a third of all advertisements on cable networks. Schor (2004) suggests that cable companies such as Nickelodeon place such advertisements during children's programs to influence what has been called the “influence market.” McNeal (1992), a leading scholar in children's consumer behavior, posits that children are three markets in one – they spend their own money (current market), they influence their family's purchases (influence market), and, through their own consumer experiences as children, they can become brand loyal into adulthood (future market). As part of the influence market, children in the United States have had more of a voice in parental purchases to the extent that many parents now believe that they know less about products than their children (Schor, 2004). Moreover, by 1983, over 70% of children's television programming hours came from cable (Pecora, 1998). Therefore, it would be expected that children would be watching cable more than network children's programming and, thus, would be influenced by the prevalence of “other” adult-oriented advertisements.

The 1990s marked an era of change in other ways. First, by the end of the 1990s, the distribution of toy advertisements returned to those found in the 1950s, with a decrease in commercials for toys to 10% by 1999 (Byrd-Bredbenner, 2002). Second, the percentage of advertisements for candy and snacks reached an all time high at 36% of all commercials (Byrd-Bredbenner, 2002). Finally, a noteworthy increase was observed in fast food advertising in the 1990s. Starting at 8.7% of advertising in 1990 (Kunkel & Gantz, 1992), fast food marketing increased to 22% of all advertising by the end of the decade (Byrd-Bredbenner, 2002). This rise in advertising of sweet, non-nutritious food has become of increased concern as the rate of childhood obesity has risen over the past 30 years. Since 1980, childhood obesity has tripled among school-age children and adolescents (Ogden, Carroll, Curtin, Lamb, & Flegal, 2010). Therefore, a number of recent studies have begun to examine the nature of advertising of food to children.

Selling Techniques and Appeals in the United States

Little has changed in the types of appeals used to advertise to children. In the 1950s, the appeal to “fun” was found in two-thirds of all ads directed toward children, followed by an appeal to “taste” (Alexander et al., 1999). Results from the 1970s indicate that appeals were closely tied to specific categories of products. For example, in food products, the most frequently used appeal was “taste” whereas “action/speed/power” and “appearance of the product” were most frequently used in commercials for toys (Barcus, 1975). Research in the 1990s found appeals being used in a similar way. “Taste/flavor/smell” was most commonly used in cereal and breakfast food ads (46.6%) and “product performance” was most commonly used in toy commercials (Kunkel & Gantz, 1992). However, it should be noted that in the advertisements for fast food restaurants, “fun/happiness” was the most common appeal used (71.9%) in the 1990s, suggesting that “good times may indeed be more important than great taste in selling hamburgers” (Kunkel & Gantz, 1992, p. 146).

Various selling techniques have been used to attract the child audience. The use of premiums and prizes declined dramatically in the 1950s. Only 11 commercials had premiums or prizes, yet nearly all of these commercials (10 or 90.7%) appeared in the first half of the decade (Alexander et al., 1999). Premiums continue to be a selling technique employed in the 1970s and 1990s, and, similarly to the use of appeals, premiums were more likely to be used for specific product categories. Premiums were more likely to be used in commercials for cereals (47%) in the 1970s (Barcus, 1975), and fast food restaurants (36.2%) in the 1990s. Therefore, the use of premiums is more likely to be associated with food items and restaurants than with other product categories. Recently, this practice has been called into question. In December 2010, the Center for Science in the Public Interest filed a lawsuit against McDonald's Corporation for use of toys as a marketing tool for its product. In 2010, McDonald's spent nearly 13% of its domestic (US) advertising dollars on marketing its meal for children known as the Happy Meal, which includes a toy with every meal (Morrison, 2011). Two counties in California have passed legislation prohibiting the inclusion of toys in kids' meals that do not meet nutritional requirements (Morrison, 2011). Other areas are now considering such a ban while some fast food restaurants are responding to these actions. In 2011, Jack in the Box removed toys from its kids' meals (Morrison, 2011).

Another practice that seems to have grown since the 1950s has been the use of disclaimers. Disclaimers provide additional information about a product in order to avoid misleading the consumer. However, most disclaimers use adult-oriented language such as “some assembly is required” or “part of a balanced breakfast.” Children who are 8 years old and younger often do not understand the disclaimer and show greater comprehension of the intent of the disclaimer when simpler language is used such as “you must put this together” (Liebert, Sprafkin, Liebert, & Rubinstein, 1977; Palmer & McDowell, 1981; Stutts & Hunnicutt, 1987). In the 1950s, only five commercials (8.3% of ads directed toward children) contained disclaimers (Alexander et al., 1999). However, disclaimers became much more prevalent in the 1970s and 1990s. Disclaimers could be presented either in a visual depiction, strictly audio voiceover, or both. In the 1970s, audio disclaimers were most common (22%), followed by visual disclaimers (11%) (Barcus, 1975). Only 8% used both audio and visual cues simultaneously to reinforce the message (Barcus, 1975). Similarly, although more disclaimers were present in the 1990s, audio disclaimers (49.6%) continued to be used more commonly than video (32.1%) or a combination of audio and video disclaimers (18.3%) (Kunkel & Gantz, 1992).

From Old to New Media: Digital Natives in their Digital World

Born into the world as “digital natives,” today's youth spend their childhood surrounded by digital technologies and are “‘native speakers’ of the digital language of computers, video games, and the Internet” (Prensky, 2001, p. 1). As such, they have different life experiences than their parents, the “digital immigrants” (Prensky, 2001, p. 2). Indeed, for today's youth, use of mobile and online media has become a standard activity. A recent study of 8- to 18-year-olds found that 20% of their media consumption (2:07) happens on mobile devices such as cell phones, iPods, or handheld videogame players (Rideout et al., 2010). Furthermore, home Internet access has grown to nearly 84% among young people, and 59% of today's youth have high-speed Internet access (Rideout et al., 2010). Given the changes in children's screen use and the continued growth of new technologies, research has begun to examine the role of advertising in these new digital environments for children.

Digital environments provide opportunities for engagement that have never been experienced before with traditional media forms. Digital television allows for the convergence of Internet and broadcasting in which viewers may click on icons on the screen to get to websites (FCC, 2000). While this has the potential to be an incredible educational tool, there is also the hazard that children are one click away from direct sales and interactive advertising. Children can play in “branded environments” (Montgomery, 2001, p. 641) in which content and advertising are blended together until they become seamlessly integrated. Therefore, research has begun to better understand the nature of these sites, the impact of advergaming and online advertising on the lives of children, and the connections between television advertising and online marketing.

The separation of content and advertising can be particularly difficult for young children. Rossiter and Robertson (1974) submit that there are a number of cognitive distinctions that children must acquire in order to understand the purpose of advertising. Among those, children must recognize and distinguish between the informational function of advertising and its persuasive intent. Robertson and Rossiter (1974) suggest that recognition of persuasive intent requires higher cognitive processing skills. Indeed, Blosser and Roberts (1985) submit that the informational dimension of advertising is recognized first and even some preschoolers are able to indicate comprehension of this dimension (Macklin, 1987). Given this development of understanding, young children in particular may perceive advertising as informative rather than persuasive.

Under the guise of knowledge provider, advertising offers a great deal of information about various products and services. Recently, children have been directed to websites from commercials to learn more about what they see on television. In a content analysis of non-program content during children's Saturday morning television, I found that almost half (44.6%) of the commercials provided website addresses for the products or services advertised (Jennings, 2006). A third of the commercials for fast food restaurants had website addresses and seven of ten commercials (70.8%) for toys contained website links. Advertisers can then lead children to these digital environments by informing them of where to go.

Advertising success online is measured in part by the length of time individuals spend on the website (Montgomery, 2001). In order to keep children at these sites, advertiser-sponsored videogames known as “advergames” (Moore, 2006) have been developed. Gaming is an especially good way to keep children on a particular website since 19% of children's daily computer time is spent playing computer games (Rideout et al., 2010). Moreover, online gaming is the most frequently reported online activity for preschoolers and children in kindergarten through the fifth grade (DeBell & Chapman, 2006).

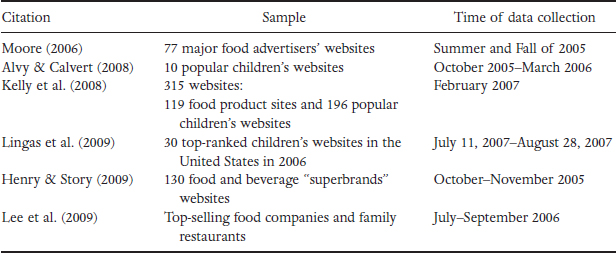

Very few studies have been published concerning advergaming and online advertising to children. Of the content analyses that have been published, all of them have focused on Internet food marketing (see Table 2.1). Elizabeth Moore provided the first in-depth examination of advergaming in her work with the Kaiser Family Foundation (Moore, 2006), in which she described the state of online food marketing in detail. Her work has stimulated further research in the area. Of the studies concerning online food marketing, different samples of websites have been drawn resulting in different types of findings. Therefore, the results will be discussed based on the nature of the sample, either websites that sell food products or popular children's websites.

Table 2.1 Content analyses of websites concerning food marketing

Popular Children's Websites

Food is commonly mentioned on websites that children frequent often. Kelly and her colleagues (2008) found food references on 43.9% of popular children's websites accounting for 932 food references. The amount of food references on popular children's websites varies, however, by site. Alvy and Calvert (2008) found tremendous variability in the presence of food on children's websites, ranging from none (on 3 of the 10 websites studied) to up to 241 instances of food marketing. However, one website takes the lion's share (78%) of food marketing references because it is a site for food/snacks (candystand.com). Of the websites that were not food-selling sites, 67 references were made to food, with half of those present on one website (Neopets.com) (Alvy & Calvert, 2008). In another study of 28 popular children's websites, 93 unique food products were referenced within one link from the home page of these sites (Lingas, Dorfman, & Bukofzer, 2009). Clearly, online food marketing is readily accessible from popular children's websites.

Further analyses of these foods advertised on children's websites indicate that often these foods are non-nutritional. Of the 93 unique products advertised in 28 children's websites, nutritional information was available for 77 specific products mentioned. Of those, only two products (Nestlé Juicy Juice Harvest Surprise and Quaker Oats Oatmeal) met the Institute of Medicine's tier 1 criteria for nutritional foods recommended for children (Lingas et al., 2009). The majority of the products (52%) fell into tier 3 as foods that are not recommended for any child at any time during their school day (Lingas et al., 2009). Similarly, Kelly and her colleagues (2008) found significantly more food references for unhealthy foods (60.8%) compared to healthy foods (39.2%). Moreover, a higher proportion of unhealthy foods appeared on websites targeted to adolescents (76.0%) than the general population (60.6%) or young children (58.6%) (Kelly, Bochynska, Kornman, & Chapman, 2008). Combined, the ease of access to food marketing and the abundance of unhealthy food advertised raise concerns, particularly related to the rise of childhood obesity worldwide.

Food Marketing Websites

Various strategies are used to attract children to food-selling websites. Moore (2006) identified six major types of online activities to attract and keep children, including: (1) advergaming, (2) brand exposure beyond games, including television commercials, (3) extension of online activities offline, (4) customization of online experience, (5) marketing partnerships and brand alliances, and (6) educational activities. These activities encompass a wide variety of techniques that are particularly appealing to children and useful for advertisers to establish brand identity.

One of the most prevalent and publicized strategies is the use of advergames, which fuse online gaming with advertising by embedding brands and products in the game play. While this technique has been well publicized, not all websites emphasize or use games. Advergames are more likely to appear on websites with a designated children's area (84%) than on websites without children's areas (19%) (Henry & Story, 2009). Similarly, Moore (2006) indicated that 73% of sites posted one or more games containing food brands, and the majority of games on top food marketers' websites (87.6%) contain some type of brand identifier (Lee, Choi, Quilliam, & Cole, 2009).

Various game features contribute to the game engagement. First, over a third (39%) of games allow the user to personalize their experience in the game by selecting players and opponents, or designing the game space (Moore, 2006). Second, a number of features are used during game play to sustain a child's interest in the game. These techniques include multiple levels of play (45%), game points as awards (69%), and time limits for game play to encourage repeated play (40%) (Moore, 2006). A third way to extend play time and game engagement is to specifically ask a player to “play again?” at the end of the game. This technique was present in 71% of the advergames on food marketing websites (Moore, 2006). Finally, to entice competition and motivate players, gamers are invited to post their high scores to a leader board (39%) (Moore, 2006).

Brand identity is a key element to advergames. This is accomplished in a variety of ways. First, integration of brand identifiers as active game components contributes to brand identity. Various items can be used as game components such as brand logos (43%), brand spokescharacters (41.6%), branded food items (39.6%), and product packages (37.2%) (Lee et al., 2009). Second, brand identifiers can also appear as tools or equipment within the game. For example, 46.7% of advergames used brands as primary objects that children were required to obtain in order to win the game (Lee et al., 2009). Another way is to incorporate food items into game play. Over half (58%) of advergames use food items as primary game pieces (Moore, 2006). Third, brand identifiers may be used to decorate the game frame. Brand logos appear in 89.3% of advergame frames, followed by brand spokescharacters (26%), product packages (16.9%), and branded food items (8.0%) (Lee et al., 2009). Finally, most games have multiple brand identifiers (Lee et al., 2009; Moore, 2006). Eighty percent of advergames contain two or more brand identifiers (Moore, 2006).

Beyond advergaming, other techniques expose children to food brands. First, television commercials appear on websites. While Kelly and her colleagues (2008) found commercials on 20.2% of food product websites, Moore (2006) discovered that over half (53%) of websites for food have commercials available for viewing. Second, the presence of brand spokescharacters can further enhance brand exposure. Over half (55%) of websites with designated children's areas used brand spokescharacters as a marketing technique. Similarly, Kelly and her colleagues (2008) found that websites targeting young children were far more likely to have promotional spokescharacters (57.9%) than those targeting adolescents (21.4%) or the general population (8.1%).

Websites offer opportunities to interact with the product offline as well. First, downloadable items such as screen wallpaper, screensavers, desktop items, and coloring pages are readily available. Kelly and her colleagues (2008) found this practice significantly more often on websites targeting young children (52.6%) rather than the general population (32.5%) and adolescents (28.6%). Indeed, according to Moore (2006), 76% of food websites targeted to children offer a downloadable item, and half (52%) offer two or more items. Second, through consumption of products offline, consumers can earn points or codes that can be accumulated for rewards. Thirty-nine percent of sites offered these programs in child-directed food marketing websites, and among those sites that do offer these programs, 97% offer points that consumers obtain from food product packages (Moore, 2006). A third way in which consumers can interact with products offline is through recipes that involve the advertised food. Almost a quarter (23%) of food marketing websites provided recipes that featured the brand as an ingredient and, of those, 80% were child-friendly recipes that can be prepared without adult assistance (Moore, 2006).

Customization of websites and development of website communities are other techniques to maintain interest in and repeated visits to websites. Website memberships were available on 38.7% of websites studied by Kelly and her colleagues (2008). However, nearly 70% of websites with a designated children's area allowed the user to register or create an account on a brand home page (Henry & Story, 2009). Moreover, Henry and Story (2009) found that designated kid's clubs were available for children to join on 37% of websites with designated children's areas. Website membership permits special privileges to its members which can lead to the customization of the Internet experience. For example, Moore (2006) found that on gushers.com, members have the opportunity to create and decorate their own virtual room, which can be updated and redecorated on return visits.

Marketing partnerships through sponsorships, promotions, or media tie-ins were also found on several food marketing websites. Most of the websites (79%) with designated children's areas had promotional tie-ins such as celebrities or athlete endorsers or sporting events (Henry & Story, 2009). Sports celebrities were most often found on websites targeting adolescents (28.6%) compared to those targeting children or the general population (Kelly et al., 2008). Moreover, almost half (47%) of websites incorporated some form of television or movie tie-in (Moore, 2006). For example, Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith was part of marketing techniques on seven different websites (Moore, 2006). Almost a third (31%) of the sites had a movie tie-in, a quarter of the sites (25%) had a tie-in to one or more television shows (32 different shows overall), and 9% of the sites had both a movie and television show tie-in (Moore, 2006).

Educational content is also available on food marketing websites. This comes in the form of nutritional information and in what Kelly and her colleagues (2008) describe as “advercation” (p. 1183), such that the food product or the brand is integrated into an educational lesson. Two-thirds (66.4%) of the food product websites studied by Kelly and her colleagues (2008) contained basic nutritional information and information about allergens. However, Moore (2006) found that basic nutritional information was more likely to be found on websites for the general population (88%) than on websites for children and teens (38%). Interestingly, advercation (79.0%) was more prevalent than nutritional information (66.4%) (Kelly et al., 2008). However, Moore (2006) noted far fewer instances of advercation with only a third of websites using this technique.

Various features for protection of children were also noted on many of the food marketing websites. Nearly all of the sites (97%) in Moore's 2006 study contained information explicitly labeled for parents. This information included a disclosure on what information is collected about children visiting the website, management of “cookies,” legal information, and Internet safety tips (Moore, 2006). Indeed, Kelly and her colleagues (2008) found that 87.4% of websites had legal information, and 68.9% of websites had statements about “cookies.” “Ad break” warnings were present on some websites. Moore (2006) found that only 18% of websites had “ad break” or “ad alert” warning to designate and identify advertising content. Henry and Story (2009) found this to be more frequently used on websites with a designated children's area (32%) than on websites without a designated children's area (1%). Fortunately, when “ad breaks” were provided, they often appeared on multiple locations throughout the site (Moore, 2006).

Discussion and Conclusion

Advertising continues to be a central component of children's media, whether in traditional forms of television or on newer technologies such as the Internet. Interestingly, the blurring of the line between advertising content and programming content continues to be a struggle throughout the history of children's media. Governmental policies speak to a need for a separation of advertising and content, but corporate strategies push them together.

Convergence seems to be a binding element in the contemporary advertising environment. First, children are using multiple media devices to reach different types of media content. For the first time since 1999, children's time spent with traditional television decreased, to be replaced with new ways of reaching TV content on their mobile devices (Rideout et al., 2010). Moreover, young people use the computer on average about an hour per day (1:03) to listen to music, watch TV, and play DVDs (Rideout et al., 2010). The lines of access to content have become blurred. Second, children are eating, wearing, and playing with media tie-in and branded products. The proliferation of media tie-ins has become so commonplace that it has become a part of everyday living for children. Their on- and offline play through branded environments has become a natural state. This convergence of media and marketing manifests itself in their desires for products. In a study of children's Christmas wishes, I found that almost three-fourths (73.7%) of all toy wishes were media-related as either requests for videogames or videogame systems (48.3%) or as media-branded toys (25.4%) such as Bratz dolls or Star Wars Legos (Jennings, 2009). Interestingly, as children got older, their requests for toys decreased while their requests for media products increased (Jennings, 2009). Media-related toys may provide a scaffolding for the transition to media devices.

The omnipresence of media and marketing in the United States may be having a greater influence on children and consumerism than ever imagined due to the continued convergence of the two. According to Moore (2004), “advertising, entertainment, and the brand experience reinforce and flow into one another” (p. 164). Preston and White (2004) suggest, “In this process [of branding], kids are transformed not simply into consumers but into marketing tools as well. The branded child becomes a living billboard for the desirability of products and the lifestyles that are linked to them . . . carrying it into different cultural spaces and relationships” (p. 126). With this blending of advertising, branding, entertainment, and education, this new media environment is “like water to a fish . . . [and] . . . remains hidden” (McLuhan & Nevitt, 1973, p. 1). It saturates the US lifestyle to such an extent that the individual is often unaware of its influence.

Future research needs to explore more closely the child's branded environment. First, a detailed look at websites other than food marketing sites is necessary. Children's play has incorporated many digital aspects. They engage in online games, indeed, but not just on food marketing sites. Therefore, a closer look at other sites, particularly toy sites, is necessary. Second, cultural expectations of advertising saturation need to be explored. Media tie-ins and branded logos can be seen in almost every corner of a child's life from the toys they play with to the books they read. Indeed, recognition of letters in advertising and company logos has begun to be referred to as “environmental print” and as a way to teach early literacy skills to young children (Horner, 2005). Third, more updated information about children's advertising on television is essential. The literature on children's advertising seems to disappear at the beginning of the new millennium. Perhaps this, too, is a reflection of the cultural acceptance of advertising and marketing practices.

The presence of advertiser-supported media coupled with media-licensed or character merchandise has become normalized. The distinction between where the advertisement ends and the content begins no longer exists, particularly as children's play both on- and offline becomes a branded environment. Since children are early adopters of new technologies and new media, they are inducted into a media culture and hence a branded culture early in life. Revisiting public policy and cultural expectations concerning the “clear separation” principle becomes even more important in the digital world. The water in which children now tread is murky, and further examination of the water is needed.

REFERENCES

Alexander, A., Benjamin, L. M., Hoerrner, K. L., & Roe, D. (1999). “We'll be back in a moment”: A content analysis of advertisements in children's television in the 1950s. In M. C. Macklin & L. Carlson (Eds.), Advertising to children: Concepts and controversies (pp. 97–115). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Alexander, A., & Hoerrner, K. L. (2007). How does the US government regulate children's media? In S. R. Mazzarella (Ed.), 20 questions about youth and the media (pp. 29–44). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Alvy, L. M., & Calvert, S. L. (2008). Food marketing on popular children's web sites: A content analysis. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 108(4), 710–713. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.01.006

Atkin, C., & Heald, G. (1977). The content of children's toy and food commercials. Journal of Communication, 27(1), 107–114.

Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2005, November). Children's television standards 2005. Retrieved from http://www.acma.gov.au/webwr/aba/contentreg/codes/television/documents/childrens_tv_standards_2005.pdf

Australian Communications and Media Authority. (2007). Children's viewing patterns on commercial, free-to-air, and subscription television. Retrieved from http://www.acma.gov.au/webwr/_assets/main/lib310132/children_viewing_patterns_commercial_free-to-air_subscription_television.pdf

Barcus, F. E. (1975). Weekend commercial children's television – 1975. Cambridge, MA: Action for Children's Television.

Barcus, F. E. (1979). Children's television: An analysis of programming and advertising. New York, NY: Praeger.

Barcus, F. E. (1980). The nature of television advertising to children. In E. L. Palmer & A. Dorr (Eds.), Children and the faces of television: Teaching, violence and selling (pp. 273–285). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Blosser, B. J., & Roberts, D. F. (1985). Age differences in children's perception of message intent: Responses to television news, commercials, educational spots, and public service announcements. Communication Research, 12(4), 455–484.

Broadcasting Commission of Ireland. (2003, October). Children's advertising code: Research into children's viewing patterns in Ireland. Retrieved from http://www.bci.ie/documents/viewer_research.pdf

Bryant, J. A. (2007). How has the kids' media industry evolved? In S. R. Mazzarella (Ed.), 20 questions about youth and the media (pp. 13–28). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Byrd-Bredbenner, C. (2002). Saturday morning children's television advertising: A longitudinal content analysis. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 30(3), 382–403.

Condry, J., Bence, P., & Schiebe, C. (1988). Nonprogram content of children's television. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 32, 255–270.

DeBell, M., & Chapman, C. (2006). Computer and Internet use by students in 2003. National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 2006-065.

Federal Communications Commission. (2000). Notice of proposed rulemaking: Children's television obligations of digital television broadcasters. Washington, DC: Author.

Federal Communications Commission. (2004). Report and order and further notice of proposed rulemaking: Children's television obligations of digital television broadcasters. Federal Register, 70, 25–38.

Federal Communications Commission. (2006). Joint proposal of industry and advocates on reconsideration of children's television rules. Washington, DC: Author.

Gantz, W., Schwartz, N., Angelini, J. R., & Rideout, V. (2007). Food for thought: Television food advertising to children in the United States. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/7618.pdf

Gunter, B., Oates, C., & Blades, M. (2005). Advertising to children on TV: Content, impact, and regulation. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Henry, A. E., & Story, M. (2009). Food and beverage brands that market to children and adolescents on the Internet: A content analysis of branded web sites. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 41(5), 353–359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2008.08.004

Horner, S. L. (2005). Categories of environmental print: All logos are not created equal. Early Childhood Education Journal, 33(2), 113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10643-005-0029-z

Jennings, N. (2006, August). Advertising and promotions in children's programs in the new millennium. Refereed Paper Poster Session at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, San Francisco, CA.

Jennings, N. (2009, November). From sugar-plums to Bratz dolls and cell phones: Children's Christmas wishes and advertising. Presentation in the Mass Communication Division for the National Communication Association Conference, Chicago, IL.

Kelly, B., Bochynska, K., Kornman, K., & Chapman, K. (2008). Internet food marketing on popular children's websites and food product websites in Australia. Public Health Nutrition, 13(11), 1180–1187. doi: 10.107/S1368980008001778

Kunkel, D. (2001). Children and television advertising. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 375–394). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Kunkel, D., & Gantz, W. (1992). Children's television advertising in the multichannel environment. Journal of Communication, 42(3), 134–152.

Kunkel, D., & Gantz, W. (1993). Assessing compliance with industry self-regulation of television advertising to children. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 2(21), 148–162. doi: 10.1080/00909889309365363

Kunkel, D., & Wilcox, B. (2001). Children and media policy. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 589–604). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lee, M., Choi, Y., Quilliam, E. T., & Cole, R. T. (2009). Playing with food: Content analysis of food advergames. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 43(1), 129–154.

Liebert, D. E., Sprafkin, J. N., Liebert, R. M., & Rubenstein, E. A. (1977). Effects of television commercial disclaimers on the product expectations of children. Journal of Communication, 27(1), 118–124.

Lingas, E. O., Dorfman, L., & Bukofzer, E. (2009). Nutrition content of food and beverage products on web sites popular with children. American Journal of Public Health, 99(3), S587–S592.

Macklin, M. C. (1987). Do young children understand the selling intent of commercials? Journal of Consumer Affairs, 19, 293–304.

McLuhan, M., & Nevitt, B. (1973). The argument: Causality in the electric world. Technology and Culture, 14(1), 1–18.

McNeal, J. U. (1992). Kids as customers: A handbook of marketing to children. New York, NY: Lexington Books.

Montgomery, K. C. (2001). Digital kids: The new on-line children's consumer culture. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 635–650). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Moore, E. S. (2004). Children and the changing world of advertising. Journal of Business Ethics, 52, 161–167.

Moore, E. S. (2006). It's child's play: Advergaming and the online marketing of food to children. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/7536.pdf

Morrison, M. (2011, June 21). Jack in the Box eliminates toys from kids' meals: But is fast feeders move more of a PR stunt? Advertising Age. Retrieved from http://adage.com/article/news/jack-box-eliminates-toys-kids-meals/228334/

Ogden, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., Lamb, M. M., & Flegal, K. M. (2010). Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(3), 242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012

Palmer, E. L., & McDowell, C. N. (1981). Children's understanding of nutritional information presented in breakfast cereal commercials. Journal of Broadcasting, 25, 295–301.

Pecora, N. O. (1998). The business of children's entertainment. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants Part 1. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1, 3–6.

Preston, E., & White, C. L. (2004). Commodifying kids: Branded identities and the selling of adspace on kids' networks. Communication Quarterly, 52(2), 115–128.

Quinn, R. M. (2002). Advertising and children. Dublin: Broadcasting Commission of Ireland. Retrieved from http://www.bci.ie/documents/advertising_children.pdf

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2: Media in the lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf

Robertson, T. S., & Rossiter, J. R. (1974). Children and commercial persuasion: An attribution theory analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 1(1), 13–20.

Rossiter, J. R., & Robertson, T. S. (1974). Children's TV commercials: Testing the defenses. Journal of Communication, 24(4), 137–145.

Schor, J. B. (2004). Born to buy: The commercialized child and the new consumer culture. New York, NY: Scribner.

Snyder, R. J. (1995). First-year effects of the 1990 Children's Television Act on Saturday morning commercial time. Communications and the Law, 17, 67–74.

Stutts, M. A., & Hunnicutt, G. G. (1987). Can young children understand disclaimers in television commercials? Journal of Advertising, 16(1), 41–46.

Szybist, J. (2011). Is TV on the decrease? Current findings on children's TV consumption. Televizion: Children's Television and Beyond, 24, 26.