10

A Critical Analysis of Cultural Imperialism

From the Asian Frontlines

ABSTRACT

Asian cultural industries have produced and exported domestic television programs and films on a large scale since the mid-1990s, challenging scholars' theories of cultural imperialism. The process remains complex, however, because the US still dominates the Asian cultural market and has expanded its influence through massive capital investments. This chapter analyzes the nature of transnationalization for Asian cultural industries in order to establish whether cultural imperialism is phased out in Asia. It explores the flows of Asian cultural products and examines the import and export of these goods in recent years. It then challenges the assertions made by scholars who formulate a reverse cultural imperialism thesis, and it questions whether cultural imperialism is still useful in explaining the Asian cultural market.

Over the last decade the production of Asian popular culture has increased: its creations have entered Western as well as Asian markets. From Korean dramas to Chinese films and from Bollywood movies to Japanese animation and console games, Asian cultural products have become globally popular. Despite the increasing scholarship that examines the role of Asian cultural products or of their industries, there is no consensus on Asia's role in the global cultural markets. In particular, the rapid growth of Asian cultural products has raised the question whether cultural imperialism is a reliable characterization of contemporary Asian cultural markets. In fact some media scholars have already sounded the death knell for cultural imperialism as a useful concept in media production studies.

Asian countries have different languages, economies, and political situations; therefore it is not an easy task to consider them as a whole, in an attempt to evidence cultural imperialism or its alternatives. It is also difficult to confirm that Asian popular culture has irrefutably earned dominance in the global market, due to the limited period of its transnational circulation. In other words, it is premature to conclude that the current boom of Asian popular culture is a transitory phenomenon or that it will last longer. Beyond this, however, the present chapter argues that US influence has never decreased; instead it has rapidly increased, through a new transnational guise and amidst market liberalization in several Asian countries.

The chapter discusses the recent development of Asian cultural industries, in particular film and broadcast industries, to demonstrate the increasing role of Asian popular culture in the global market. It is not meant to examine the causes behind the increase in Asian cultural exports. It investigates instead whether the recent growth of regional cultural industries justifies a shift away from the norm of the cultural imperialism thesis. Historically, three major critiques were adduced to this thesis. Although the three are not mutually exclusive, each critique applies to case studies based in Asia. The chapter rehearses them in order to show the relationship between cultural imperialism, its critique, and emerging Asian cultural markets. This analysis helps to establish that cultural imperialism is still a useful heuristic for explaining both the emerging Asian cultural market and the changing nature of Asian cultural industries.

Early Theses on Cultural Imperialism

Since the late 1960s media researchers all over the world have discussed the unequal flows of television programs and motion pictures from Western to developing countries in terms of cultural imperialism. Imperialism involves an extension of power or authority over others, with a view to domination, and it results in the political, military, or economic dominance of one country over another (Wasko, 2008). Cultural imperialism extends this definition to incorporate the cultural imbalances and inequalities between rich and poor nations that result from economic and technological gaps between them (UNESCO, 1980). An early theorist of cultural imperialism, Herbert Schiller, argued that the economic dominance of the US and a few European nations over the global flow of media products had cultural impacts:

The concept of cultural imperialism describes the sum of processes by which a society is brought into the modern world system and how its dominating stratum is attracted, pressures, forced, and sometimes bribed into shaping social institutions to correspond to, or even promote, the values and structures of the dominant centre of the system. (Schiller, 1976, pp. 9–10)

Schiller's thesis focused on the conjunction of US entertainment, communication, and information (ECI) industries, and it was further developed by a range of communication scholars worldwide, who found empirical evidence of imbalanced cultural flows in the specific areas of news, television, film, and other forms of entertainment (Beltran, 1978; Dorfman & Mattelart, 1991; Guback, 1984; Nordenstreng & Varis, 1974; Tunstall, 1977; Varis, 1974). For example, through a survey of the buying and selling of TV programs in 50 countries, Tapio Varis (1974) concluded that the flow of information, television dramas, and news items is one-sided between Western and non-Western countries. Nordenstreng and Varis (1974, p. 52) also pointed out that, “globally speaking, television traffic does flow between nations according to the one way street principle: the streams of heavy traffic flow one way only.” Armed with data demonstrating the one-way flow of cultural goods from Western to non-Western countries and from Northern to Southern countries, scholars of cultural imperialism in the 1970s and 1980s implied that non-Western and Southern countries were victims of parallel imperialisms, which helped the Western and the Northern countries maintain commercial, political, and military superiority. Grounded in the nation-state, US media corporations were the most notorious in these studies, not only for the power they exerted over cultural economies elsewhere, but also for the threat they posed to indigenous and local cultures internationally. Despite these grand statements, Asian countries were nearly absent from research agendas until the mid-1990s, when the consumer market for popular culture emerged as a national, and then as a global force.

Challenges to Theses of Cultural Imperialism

Since the early 1990s cultural imperialism theses have come under increasing scrutiny, in light of the growth of cultural industries in those Eastern and Southern countries supposedly dominated, respectively, by the West and the North. In particular, several Asian countries have rapidly developed their own cultural industries, which have infiltrated markets in other parts of the world. The growth of film industries in Asia – for example, the “Korean Wave,” which symbolized the wave of Korean dramas and films across Asian markets, and “Bollywood,” the Hindi-language film industry based in India – have challenged theses on cultural imperialism under three rubrics: (1) the development of local cultural industries; (2) peripheral vision; and (3) active audiences. Together, these rubrics have contributed to the formation of what might be called globalization theory.

The Development of Local Cultural Industries

Tracy (1988) states that Third World media producers strengthened their national cultural industries to compete with once dominant US and European cultural industries. As a result, cultural imperialism no longer exists. Proponents of this critique (see also Straubhaar, 1991 and Reeves, 1993) point to the rise of media conglomerates, such as Televisa in Mexico and Globo in Brazil, which not only defend their own national cultures, but also export these cultural messages to neighboring countries. In the Asian context, the Korean Wave provides a ready example of the ways local cultural production may counter cultural imperialism. Although Korea seemed completely captured by foreign film and television companies by the late 1980s, investment from both the government and private sectors in cultural industries in the late 1990s seemed to reverse one-way flows between Korea and the West.

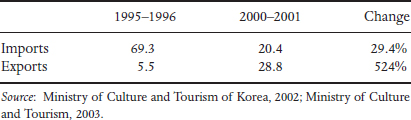

Table 10.1 Sales in the Korean television market

In the television market alone, Korea's imports dropped by a factor of three and increased fivefold as Korean-made television programs appeared in China, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Japan (see Table 10.1). Although these figures would reverse once again by 2007 – a fact to be discussed in more detail later – they indicate that the growth of local cultural industries may reduce the possibility of cultural imperialism.

Peripheral Markets

A second critique of cultural imperialism emphasizes how countries located on the peripheries of world capitalism, namely those that used to be the dumping grounds for US and European cultural products, have become economically interdependent in recent years. Drawing implicitly on Wallerstein's (1974) distinctions between core industrialized and peripheral markets, these scholars (see Chan, 1996; Pendakur, 2003; Shome & Hedge, 2002; Sinclair, Jacka, & Cunningham, 1996) provide ample evidence of Western markets that import cultural products from peripheral countries. Chinese films and co-productions, such as Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, have become major box-office successes in mainstream US movie theaters. Bollywood films screen in movie theaters across major US cities with large Indian American populations. There are even theatres that exclusively show Bollywood films in Vancouver, Canada. While Wallerstein considered China and India “semi-peripheral” countries due to their rapid industrialization, their cultural presence in Western markets at the very least destabilizes strict notions of cultural imperialism as a one-way flow of goods from the West to the East. It is also interesting to note that many countries that neighbor China or India, for example Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, and Cambodia, fear the encroaching imperialism of these “semi-peripheral” countries due to the shortage of resources, skills, and technologies in their own domestic cultural markets. Although core–periphery is a relational concept, periphery-vision proponents have adapted the existing core-periphery model to a more complex and global cultural economy.

Active Audiences

Another main line of attack on the cultural imperialism thesis focuses on the third weak link: its underestimation of local resistance to Western dominance (Curran & Park, 2000, p. 6); it cites how local audiences modify, hybridize, indigenize or transform the meaning of foreign media products through their own local frameworks for understanding. These critics of cultural imperialism emphasize consumers' active appropriation and selectiveness in their choices of media contents, showing that audiences often prefer culturally proximate contents over imported programs (Straubhaar, 1991). Supporters of active audiences have also analyzed the diverse responses of audiences outside of the US to Western media, thus debunking the supposed cultural effects of cultural imperialism. Liebes and Katz (1990) conducted seminal studies of the comparative reception of the US television program Dallas in the 1980s. They found that viewers' interpretations of the program varied according to their nationality, religion, generation, and values. These studies tempered earlier work, which considered the program a prime example of American cultural imperialism (White, 2001). In other words, they point out that cultural imperialism theses have not adequately acknowledged audience members' abilities to process information and to interpret messages in different ways, on the basis of their individual backgrounds. Primarily due to these cases, Mirrlees (2008, p. 177) bluntly claims that cultural imperialism theses failed to address the complexity of local audience reception practices.

Critiques of Cultural Imperialism and Globalization Theory

By the late 1990s studies of globalization took the place of studies of cultural imperialism as the key issue in the study of media production outside of the US and Europe. Combining the three rubrics for critiquing cultural imperialism theses, theorists of globalization (Appadurai, 1996; Robertson, 1992; Tomlinson, 1991) have focused primarily on cultural issues instead of the political economy of media production. They dismissed the notion of cultural imperialism for its vague language of domination, colonialism, coercion, and imposition. Arguing that cultures and societies could no longer be analyzed in the framework of the nation-state, globalization theorists emphasized cultural pluralism and diversity over national politics or economic domination.

Media scholars have taken up globalization theory in relation to Asia most prominently through case studies of Japanese popular culture. Referencing media franchises such as Pokémon and Sailor Moon, as well as animation and manga genres, Iwabuchi (2008), Consalvo (2006), and Thussu (2007) implicitly claim that cultural imperialism is dead in Japan. Indeed, Japanese cultural exports have increased rapidly in the time period since Schiller's articulation of cultural imperialism. Japanese film production increased from 289 films in 1995 to 418 films in 2008, making Japan the third largest production market, behind the US and India (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan, 2010, p. 746). No longer confined to Samurai movies, Japan has produced several films that were successful as Hollywood remakes, such as The Ring (2002) and Shall We Dance (2004), The Grudge (2003), and Dark Water (2005). The success of Japanese console video games throughout the world has been even more striking. The worldwide game market is expected to increase from $27.1 billion in 2005 to $46 billion in 2010 (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2006, p. 368). Japan dominates this market through its dedicated consoles, which are produced primarily by two Japanese-based electronics companies: Sony and Nintendo.

Japanese media contents have found receptive homes in Asian countries. Regionally, Fung (2007a) writes that culturally proximate countries such as Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan see Japanese contents as easy to adopt and symbolically more Western than those from North America and Europe. This is because, although Japan has made its own unique cultural products, Japanese popular culture adopts the production skills, formats, and styles of Western culture, a phenomenon that makes Japanese media part of Western culture (Jin, 2009). Meanwhile, Japan deliberately markets its television dramas, comics, and cartoons within Asia by erasing its “cultural odor,” or the association of a country of origin with a cultural product (Iwabuchi, 2002, p. 95). This was necessary in order to erase the historical legacy of the Japanese as imperial oppressors in the region (Lee, 2004). Through this strategy, Iwabuchi (2008, pp. 145–146) asserts that Japan has escaped from American cultural dominance.

The dominance of Japan in global popular culture markets has led the cultural studies scholar Stuart Hall to conclude that Japan is actually closer to the West than to the East:

These days, technologically speaking, Japan is Western, though on our mental map it is about as far East as you can get. By comparison, much of Latin America, which is in the Western hemisphere, belongs economically to the Third World, which is struggling – not very successfully – to catch up with the West. (Hall, 1996, p. 185)

Hall's point echoes those of others, who have considered Japan as part of the semiperiphery (cf. Schiller, 1976; Wallerstein 1974) – neither part of the dominant core in the West nor part of the victimized periphery in the East – when evaluating its media production. Even Iwabuchi's contention that Japan escaped cultural imperialism only by indigenizing American influences suggests that scholars take another look at what cultural imperialism means in a globalized media economy.

A New Look at Cultural Imperialism

Contrary to the opinion of critics of the cultural imperialism thesis, Western dominance in the Asian market has not decreased at all. Western, and predominantly US-based or -owned, cultural industries continue to dominate cultural products and media capital. Using both formal policies and informal negotiations, the global media giants have taken advantage of the rise of Asian cable and satellite – as well as terrestrial – television channels to target Asian countries, whose populations by the mid-1990s had the largest number of television sets in the world.

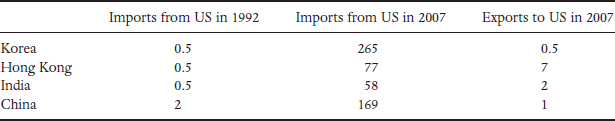

The US has increased its global exports of film and television programs exponentially worldwide, and to Asia in particular. According to the US Department of Commerce (2008, p. 50), US exports increased as many as 15 times between 1985 and 2007 (see Table 10.2). US imports of film and television programs increased during this same period as well, from $76 million in 1992 to $1,440 million in 2007, leaving a net imbalance of $13.6 billion in 2007 (US Department of Commerce, 2008). While Japan has been the largest US trading partner in Asia, Korea, Hong Kong, India, and China have risen in prominence in recent years.

As Table 10.3 illustrates, China has rapidly increased its import of American cultural products, from only $2 million in 1992 to $169 million in 2007, while India has increased from less than $1million in 1992 to $58 million in 2007. While Korea imported $265 worth of television programs and films from the US in 2007, it exported less than $500,000 worth of television programs and films to the US during the same year (Table 10.3; US Department of Commerce, 2008, pp. 50–51). As previously explained, the direct flow of cultural products from the US to Korea had decreased for a while; however, the import of foreign television programs and films, in particular from the US, again increased to 63.8% between 2005 and 2007, mainly due to the reduction of the screen quota system, which has resulted in the surge of Hollywood films. The market share of domestic films indeed decreased from around 62% in 2006 to 48% in 2008, when Hollywood films dominated the Korean film market (Korean Film Council, 2009, p. 4).

Table 10.2 US film and TV exports, 1985–2007 (in billions US$)

| 1985 | 1 |

| 1990 | 2 |

| 2001 | 8.57 |

| 2007 | 15 |

Table 10.3 Imports and exports of cultural products (in millions US$)

As such, Asian countries have provided new profitable markets for the US cultural industries. Market liberalization measures, which began in the early 1990s, increased cultural imports across the board, but did not have a significant effect on exports of cultural products to the US. These figures reflect the lobbies of US media giants such as Walt Disney, Time-Warner, and News Corporations, in alliance with the US government, which demanded that Asian countries, as well as Latin American countries, open their markets to US capital (Sparks, 2007, p. 138; Wasko, 2003, p. 213).

Asian countries used a variety of gatekeeping policies, ranging from outright bans and censorship to import quotas and the financing of domestic cultural productions, to restrict the influx of foreign media industries and content (Chadha & Kavoori, 2000 p. 428). The Chinese Propaganda Department took a series of steps to limit foreign television content as well as foreign ownership (p. 419). Korean regulations limited their television program imports to one fifth of the total, while asking domestic cinemas to screen films produced domestically up to a certain number of days per year. In Taiwan, at least 70% of the programming on terrestrial television stations and at least 25% of the programming on cable channels had to be locally produced (Chan, 1996, p. 134). It is hardly surprising that the strictest regulations have come in postcolonial Asian countries, where nation-building continues to be a critical issue (Sinclair et. al. 1996). Still, the result of these efforts has not turned the tide of US imports.

Some key examples emphasize the continuing dominance of global media industries in Asia. In Korea:

- Capital International (US) invested $50 million in the Korean cable company On Media, which became its second largest stockholder (21.7%) in 2000 (Cho, 2002, p. 114).

- MTV (Music Television), a Viacom affiliate, established MTV-Korea as a joint venture with On Media in 2001 (Hau, 2001, p. 60).

- In 2007 Electronic Arts, the largest video and computer game company world-wide, invested $105 million in the Korean game company Neowiz (Cho, 2007).

These examples of foreign influence, blatant in Korea, have been more subtle in China, where authoritarian politicians continue to open markets to capitalism. In 2000 China's leaders formally declared that it would partially open its communication market toward international communication, as part of China's admission to the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Khan, 2001). However, in the decade leadingup to this public admission, foreign-media power privately grew. Foreign companies could own up to 49% of Chinese video and audio distribution companies and up to 49% of companies that build, own, and run movie cinemas. Star-TV owner Rupert Murdoch, who has changed his nationality from Australian to US, and Liu Changle, a former officer in the People's Liberation Army, thus launched Phoenix as a 45/55 joint venture that would complement the Star-TV platform. While the latter continued to beam English-language sports and entertainment channels to the mainland, Phoenix had exclusive rights to air Mandarin-language movie and general entertainment channels. Phoenix, perhaps not coincidentally, emphasized news and information programming amidst China's liberalization process in 1996 (Curtin, 2005, pp. 164–165). These examples show that the Asian cultural market is not safe from Western media giants.

Global trade agreements also function to penetrate Asian markets. Whereas the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has long represented US interests in opening Third World markets (Schiller, 1999), bilateral agreements have been the weapon of choice in US trade policy. Korea, which had a 64% share of its own film market in 2006 (Korean Film Council, 2009, p. 4), lowered its own domestic exhibition quotas from 146 days to 73 days a year, in anticipation of trade talks with the US. Negotiators apparently made the cuts a precondition for a US–Korea free-trade agreement. Since the rollback, the market share of Korean domestic films fell to 42% in 2008 (ibid.).

How to interpret the globalization process is critical. Unlike the period from the 1960s to the 1980s, when the US strategized to dominate world media flows, US media giants in recent years have made use of local cultural resources in promoting their own products. Influenced less by a regard for national cultures than by market forces, these companies' executives realize that people prefer to watch programs in their own languages (Thussu, 2000, p. 184). Indeed, “think globally, act locally” is the business motto of Viacom, suggesting a localized business strategy in other parts of the world. Viacom's holding company MTV is a case in point.

MTV seized the opportunity to extend its power into Asia in the 1990s, by working with national broadcasters. MTV personnel cooperated with China's state broadcaster, China Central Television (CCTV), to produce the CCTV-MTV Music Awards in Beijing in 2001. Later on they worked with the Shanghai Media Group (SMG) to create the Style Awards in Shanghai (Fung, 2007b, pp. 72–73). Expressed in the localization strategy “local people, local programs,” MTV sells syndicated programs made in China to stations in different Chinese cities and inserts advertising between program slots. In Indonesia, MTV localized its global product by incorporating local audience tastes:

With videos played on MTV, shows may be all or mostly of Western groups, but they are selected for (and sometimes by) Asian audiences. The list often consists entirely of Western artists. Yet there are numerous shows that offer either a mix of Indonesian and foreign artists or exclusively Indonesian artists. (Sutton, 2003, p. 324)

Together, MTV's moves have made for a profitable business model. From a critical perspective, MTV's influence can be found in media contents around the world, where scholars have associated it with rank sexuality, brutish pride, and vulgarity (see Rao, 2007).

In sum, critiques of cultural imperialism, which have identified several emerging markets as evidence of the weaknesses of the cultural imperialism thesis, could not explain the case of Asian cultural markets. Asia has developed its own cultural products and exported them regionally, but it does not overtake the dominant position of the US in media production flows. Rather, Western cultural hegemony may have decreased, while Western media industries' profitability remains healthy, if not stronger. This leaves the question of long-term and cumulative effects on the audience as an open one. As Lee (2006, p. 895) has concluded:

Local reception may render the domination of Hollywood movies around the world somewhat less ominous [in the Asian context]. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that local reception does not make cultural imperialism a non-issue, because the end result of increasing Hollywood dominance would still raise concerns about the increasing lack of local voices and cultural resources available to the local audience.

Perhaps, as Anthony Fung (2007b, p. 84) argues, “it is unrealistic to assume that any nation-state can maintain itself as a fortress against new and accelerated global capital flows.” Transnational capital establishes no territorial center of power and does not limit itself with fixed boundaries or barriers. It progressively incorporates the entire global realm within its open, embracing, and expanding frontiers (Hardt & Negri, 2001, p. xii). The fact that Western corporations, supported by Western governments and international agencies, dominate the flows of cultural production is not a new phenomenon. Schiller even reframed his own argument to fit this new and expansive transnational reality:

The early formulation in the late 1960s of the cultural domination thesis occurred in a specific historical era. Although that period is over, this by no means indicates that cultural domination no longer exists. The difference is that national (largely American) media-cultural power has been largely (though not fully) subordinated to transnational corporate authority. (Schiller, 1991, p. 13)

Schiller's revision has been extended through case studies that point to the cultural dimensions of transitional corporate authority (cf. Boyd-Barrett & Xie, 2008; Chadha & Kavoori, 2000; Jin, 2007). For one, Sreberny-Mohammadi (1997, p. 51) argues:

Cultural imperialism is not maintaining its rule merely through the export of cultural products, but through institutionalization of Western ways of life, organizational structures, values and interpersonal relations, language. Cultural imperialism should be considered a multi-faceted cultural process.

Examples of these Western ways include: the introduction of commercial media systems; the systematic violation of sovereignty with supranational communication technologies; the mass distribution of false or systematically distorted images of poor nations for global audiences; and the schooling of foreign students to US or US-style media practices (Schiller, 1996, p. 102). Though the arc of US power is waning, US culture remains influential in countries, not only in terms of explicit contents, but implicitly in the ways in which contents are framed.

Indeed, the nature of the transnationalization of the cultural industries has significantly shifted. Western cultural industries have changed their strategies to adjust to the changing global environment. Instead of solely focusing on exporting their cultural goods, they have invested in cultural industries in developing countries. Through this strategy they are still able to dominate the world cultural market, and they can still penetrate the commercial ideologies of Western countries. Although some countries have developed their own unique cultural strategies and have avoided cultural homogenization through globalization strategies, one needs to understand that glocalization is another form of Western dominance. Cultural producers in Asia have tried to cooperate with Western cultural capital and cultural content, but they hardly escape from Western influence.

Conclusion

The discourse about cultural imperialism has shifted markedly over the course of the last several decades. Both proponents and opponents of cultural imperialism have offered several important approaches, which may grow one day into a new theory of cultural flows and impacts. As the globalization of media continues, Wasko (2008) predicts that the debates about the consequences of cultural flows will inevitably continue as well. Nevertheless, one should be cautious in using any one of the critiques of cultural imperialism to dismiss this phenomenon wholesale, or to replace it with a cultural theory of globalization.

It is true that Asia has become an emerging market for media production and that many Asian-based national industries successfully compete against dominant US films and TV programs. This does not mean that the inequality and imbalance in the audiovisual service sector between Western countries and Asian countries decreases significantly. While Asia plays a key role in the regional cultural market, the dominance of the US has increased even more rapidly. The few instances in which Asian popular culture has entered Western countries only reinforce the continuing power of US culture as the rule (see Maxwell, 2003). Cultural imperialism theory maintains its rule in developing countries not only through the increasing number of Western cultural products, but also through the capital investment made in local cultural industries by Western-based transnational corporations (Jin, 2007). The US dominance of cultural industries operates not only at the level of contents but also at the level of structures, techniques, and resources. In this light, Schiller (1991, pp. 14–15) pointed out:

American cultural imperialism is not dead. Rather, the older form of cultural imperialism no longer adequately describes the global cultural condition. Today it is more useful to view transnational corporate culture as the central force, with a continuing heavy flavor of US media know-how, derived from long experience with marketing and entertainment skills and practices.

Asia presents relatively little evidence of the demise of cultural imperialism. On the contrary, we have yet to see how cultural imperialism will manifest itself, if not intensify, through Western-based corporations operating under the guise of globalization.

REFERENCES

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Beltran, L. R. (1978). Communication and cultural domination: USA–Latin American case. Media Asia, 5(4), 183–192.

Boyd-Barrett, J. O., & Xie, S. (2008). Al-Jazeera, Phoenix satellite television and the return of the state: Case studies in market liberalization, public sphere and media imperialism. International Journal of Communication, 2. Retrieved July 17, 2010, from http://ijoc.org/ojs/index.php/ijoc/article/view/200

Chadha, K. & Kavoori, A. (2000). Media imperialism revisited: Some findings from Asian case. Media, Culture, and Society, 22(4), 415–432.

Chan, J. M. (1996). Television in Greater China: Structure, exports, and market formation. In J. Sinclair, E. Jacka, & S. Cunningham (Eds.), New patterns in global television: Peripheral vision (pp. 126–160). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cho, E. K. (2002). A comparative study of the business model and market strategy of global media group. Seoul, South Korea: Korean Broadcasting Institute.

Cho, J. S. (2007, March 20). US game giant EA to invest $100 m in Korean game. The Korea Times, Retrieved July 17, 2010, from https://lexisnexis.com

Consalvo, M. (2006). Console video games and global corporations: Creating a hybrid culture. New Media and Society, 8(10), 117–137.

Curran, J., & Park, M. J. (2000). Beyond globalization theory. In J. Curran & M. J. Park (Eds.), De-westernizing media studies (pp. 3–18). London, UK: Routledge.

Curtin, M. (2005). Murdoch's dilemma, or “What's the price of TV in China?” Media, Culture and Society, 27(2), 155–175.

Dorfman, A., & Mattelart, A. (1991). How to read Donald Duck: Imperialist ideology in the Disney comic [1971] (D. Kunzle, Trans.). New York, NY: International General.

Fung, A. (2007a). Intra-Asian cultural flow: Cultural homologies in Hong Kong and Japanese television soap operas. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 51(2), 265–286.

Fung, A. (2007b). Think globally, act locally: China's rendezvous with MTV Global Media and Communication, 2(1), 71–88.

Guback, T. (1984). International circulation of US theatrical films and television programming. In G. Gerbner & M. Siefert (Eds.), World communications: A handbook (pp. 153–163). New York, NY: Longman.

Hall, S. (1996). The West and the rest. In S. Hall, D. Held, & K. Thompson (Eds.), Modernity: An introduction to modern societies (pp. 185–227). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2001) Empire. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hau, L. (2001, July21). MTV enters Korean music-TV market. Billboard.

Iwabuchi, K. (2002). Recentering globalization: Popular culture and Japanese transnationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Iwabuchi, K. (2008). Cultures of empire: Transnational media flows and cultural (dis)connections in East Asia. In P. Chakravartty & Y. Zhao (Eds.), Global communications (pp. 143–162). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Jin, D. Y. (2007). Reinterpretation of cultural imperialism: Emerging domestic market vs. continuing US dominance. Media, Culture and Society, 29(5), 753–771.

Jin, D. Y. (2009). Where is Japan in media studies in the post-Cold War era? Critical discourse of the West and the East. Social Science Research, 22(1), 261–293.

Khan, J. (2001, November 11). World Trade Organization admits China, amid doubts. New York Times. Retrieved July 17, 2010, from https://lexisnexis.com

Korean Film Council (2009). Korean film industry: White Paper 2008. Seoul, South Korea: KOFIC.

Lee, D. H. (2004). Cultural contact with Japanese TV dramas: Modes of reception and narrative transparency. In Iwabuchi, K. (Ed.), Feeling Asian modernities: Transnational consumption of Japanese TV dramas(pp. 251–274). Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

Lee, F. (2006). Audience taste divergence over time: An analysis of US movies' box office in Hong Kong, 1989–2004. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(4), 883–900.

Liebes, T., & Katz, E. (1990). The export of meaning: Cross cultural readings of Dallas. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Maxwell, R. (2003). Herbert Schiller. New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

Ministry of Culture and Tourism of Korea. (2002). Cultural industry. Seoul, South Korea: Ministry of Culture and Tourism [White paper].

Ministry of Culture and Tourism (2003, February). Analysis of 2002 television program trade. Seoul, South Korea: Ministry of Culture and Tourism [Press release].

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan. (2010). Japan statistical yearbook 2010. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications in Japan.

Mirrlees, T. (2008). Review essay: Historicizing US imperial culture. Communication Review, 11, 176–191.

Nordenstreng, K., & Varis, T. (1974). Television traffic: A one-way street. Paris, France: UNESCO.

Pendakur, M. (2003). Indian popular cinema: Industry, ideology, and consciousness. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

PricewaterhouseCoopers. (2006). Global entertainment and media outlook 2006–2010. (Report.) New York, NY: PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP.

Rao, S. (2007). Globalization of Bollywood: Ethnography of non-elite audiences in India. Communication Review, 10(1), 57–76.

Reeves, G. (1993). Communications and the Third World. London, UK: Sage.

Robertson, R. (1992). Globalization: Social theory and global culture. London, UK: Sage.

Schiller, D. (1996). Theorizing communication: A history. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Schiller, H. (1976). Communication and cultural domination. New York, NY: International Arts and Sciences Press.

Schiller, H. (1991). Not yet the post-imperialist era. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8, 13–28.

Schiller, H. (1999). Living in the number one country. New York, NY: Seven Stories Press.

Shome, R., & Hedge, R. (2002). Culture, communication, and the challenge of globalization. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 19(2), 172–189.

Sinclair, J., Jacka, E., & Cunningham, S.(Eds.). (1996). New patterns in global television: Peripheral vision. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Sparks, C. (2007). What's wrong with globalization? Global Media and Communication, 3(2), 133–155.

Sreberny-Mohammadi, A. (1997). The many cultural faces of imperialism. In P. Golding & P. Harris (Eds.), Beyond cultural imperialism (pp. 49–68). London, UK: Sage.

Straubhaar, J. (1991). Beyond media imperialism: Asymmetrical independence and cultural proximity. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 8(1), 39–70.

Sutton, R. A. (2003). Local, global, or national? Popular music on Indonesian television. In L. Parks & S. Kumar (Eds.), Planet TV: A global television reader (pp. 320–340). New York, NY: New York University Press.

Thussu, D. (2000). International communication: Continuity and change. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Thussu, D. (2007). Contra flow in global media: An Asian perspective. Media Asia, 33(4), 123–129.

Tomlinson, J. (1991). Cultural imperialism: A critical introduction. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tracy, M. (1988). Popular culture and the economics of global television. Intermedia, 16, 9–25.

Tunstall, J. (1977). The media are American: Anglo-American media in the world. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

UNESCO. (1980). Many voices, one world: Communication and society today and tomorrow. Paris, France: UNESCO.

US Department of Commerce. (2008, October). Survey of current business. Washington, DC: Department of Commerce.

Varis, T. (1974). Global traffic in television. Journal of Communication, 24(1), 102–109.

Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world-system: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Wasko, J. (2003). How Hollywood works. London, UK: Sage.

Wasko, J. (2008). What is media imperialism? Journal für Entwicklungspolitik, 26(1), 36–56.

White, L. (2001, spring/summer). Reconsidering cultural Imperialism theory Transnational Broadcasting Studies Journal, 6. Retrieved July 17, 2010, from http://www/tbsjournal.com/Archives/spring01/white.html, 9.1.2008