5

The Interview

A Process of Qualitative Inquiry

ABSTRACT

The interview in qualitative inquiry extends to surveying, one-on-one in-depth investigation, impromptu ethnographic meetings, formal focus groups, and free-form dialogue, depending on the nature of the research puzzle. Researchers have called interviewing “an unfolding interpersonal drama,” “a marriage with hidden truths,” “a narrative practice,” and “an unfolding story.” At its heart, the interview entails an investigation into individual motivations, interpersonal and communal relationships, life engagement, as well as civic, familial, and other kinds of problems and resolutions. The interview's execution is both art and science, with the end result an unveiling of meaning construction, information processing, and knowledge documentation. This chapter describes the dynamics of the interview, including guidelines for building question templates (or not), navigating university institutional review boards, accessing informants, collecting the information, and then analyzing the data.

Interviewing as a mode of qualitative inquiry can unveil the process of meaning construction, the dynamics of relationships, and the formation of knowledge – if executed effectively. Called “the gold standard of qualitative research” (Silverman, 2000, pp. 291–292), the methodological technique must be approached as both a creative, malleable art form and a scientific technique that produces data. Ithiel de Sola Pool (1957, p. 193) called the interview “an unfolding interpersonal drama with a developing plot.” Two leaders in qualitative scholarship, Thomas Lindlof and Bryan Taylor (2002, p. 173), describe the interview as the act of soliciting people's stories. Gubrium and Holstein (1998) go further with the storytelling metaphor, likening the interview to the plot and regarding the interviewer as author and character. In my favorite comparison, Oakley (1981, p. 41) considered the interview as a marriage: “everybody knows what it is, an awful lot of people do it, and yet behind each closed front door there is a world of secrets.”

This chapter aims to open any closed doors to interviewing and to reveal the secrets that lie within the method. It begins with a nod to the long history that interviewing as a research method in the social sciences has accumulated before articulating a philosophy and typology of interviewing as a way to approach empirical truth seeking. Essentially, the chapter seeks to celebrate the multiple dynamics of the interview, which represents a powerful methodological tool. It is particularly well suited to studying the power and influential relationships that people have with media – the topic of this chapter. The bulk of this chapter will lay out a pragmatic guide for students of qualitative interviewing, providing practical suggestions for developing questions, drawing a sample, undergoing institutional review board interview protocols, and collecting and analyzing data. It takes as its thesis the idea that every interview exercises a power relationship in and of itself, inasmuch as it is meant to reveal power relationships. And every researcher must carefully consider the type, style, technique, tone, mode, and execution of the method in conjunction with the targeted population as well as the overall research goals.

Interviewing: A Brief History and Philosophy

From its roots, interviewing has been linked to ethnography as a way to study human conditions, cultures, and communities (Vidich & Lyman, 2003). Two early pioneers of the development of the interview method, Henry Mayhew in the 1860s and Charles Booth in the 1880s, spent time with the poor people of London in the United Kingdom and published accounts of their lives through surveys, unstructured interviews, and ethnographic observations. In approaching the people as capable of representing themselves and competent to explain their life experience, these two revolutionized the field of sociology and launched interviewing as a valid method (Converse, 1987). Furthermore, through this triangulation of qualitative data, these ethnographers established the interview data collection method as one that depended on observation as much as question protocol.

Throughout the 1900s, particularly in the United States, such as in the Chicago School, scholars turned to the interview as a key technique to understand notions such as psychological measurement, the “Other” via American exclusion, community adaptation, and opinion polling (Fontana & Prokos, 2007; Maccoby & Maccoby, 1954). By the 1960s, about 90% of data in the two top American sociological journals came from interviews and questionnaires (Brenner, 1981). From formal polling of populations to informal conversational exchange, early interviewing in qualitative work had creative, anecdotal, interpretive qualities that contrasted with post-World War II attempts to use the survey as an instrument to quantify data. Throughout the twentieth century, interviewing became more ubiquitous in all fields, including media and communication studies (Fontana & Prokos, 2007). During this period, from the 1950s through the 1960s and 1970s, the schism between qualitative and quantitative interviewing and surveying of people widened, not only in terms of how samples were drawn and data was collected via questions and items but also in the coding and analysis of the resulting transcripts (Fontana & Prokos, 2007). In the end, however, all of these scholars – quantitative and qualitative – were querying people to find out something important about society.

So much of what we read about interviewing – its dimensions, its applications, its strategies – is framed according to power and power relationships: Who shall wield the power in the interview? How shall the power manifest, and to what end? Denzin (1978) considers interview talk to be for someone else's benefit and acknowledges that inevitably one person in any conversation must exert greater control than the other(s). Ithiel de Sola Pool (1957) wrote:

The social milieu in which communication takes place [during the interview] modifies not only what a person dares to say but also even what he thinks he chooses to say. And these variations in expression cannot be viewed as mere deviations from some underlying “true” opinion, for there is no neutral, non-social, uninfluenced situation to provide that baseline. (p. 192)

Indeed, he pointed out that the dynamic contingencies of the interview itself activate opinion; even presumed knowledge extracted can be no more than the manifestation of the interview interaction (Cicourel, 1964). “Each interview context is one of interaction and relation; the result is as much a product of this social dynamic as it is a product of accurate accounts and replies” (Fontana & Frey, 2008, p. 64). Fontana and Frey went on to describe the interview as “an active, emergent process” (p. 76), but I would ask: Who leads that process and who submits? And, more importantly, why? Do the resulting power dynamics innate in the technique itself influence the data outcome? If we accept that the interview itself is a “social encounter,” as Holstein and Gubrium (1995, p. 3) do in their advocacy of an “active approach” to interviewing, we must understand that the interview interaction itself must bias any derived data.1 Because every interview involves a communicative exchange of more than one person and because none of us can read minds, every question and every answer hold the possibility of misinterpretation, nuance, and mistaken emphasis. It is the responsibility of the researcher to parse out what is really going on as much as possible. This fundamental reality shall be present at every stage of the methodological process – from beginning to end.

The question of power is an important one whenever an interview protocol is developed. The effect of a male interviewing a female, a youth interviewing an elder, a White person interviewing a minority ethnic person can sometimes arise in validity concerns: Is the participant articulating a response based on a reaction to the interviewer or was her response true to her internal processing? Therefore, the understanding of those power dynamics must be incorporated into the context of the answers, but also into the very approach of the interview and the protocol. Complete background and demographical information about the informant must be collected, even as the personal history must not trump any contemporary meaning discussion. Approaching the interview data later on from a dialogic perspective will adapt the frame so that any power influence can be considered as one version toward the truth; that version is just as interesting as any other “real” answer, had the interviewer been Black or old or female. It is essential that the context of the information exchange be documented and analyzed accordingly. “Any transcription of speech must be understood as a compromise” (Elliott, 2005, p. 51).

This power question is also relevant at the beginning of the interview process, when the sample is determined: Who will be privileged to speak? Students often ask how many people they must interview to achieve methodological saturation, and I respond that this is the wrong question. Rather, they should be asking, “Who in my target population or community must share information if I am to understand this research puzzle?” The answer to that first question will be answered with the response to the second. If one is interested in power dynamics within an information producing community, for example, the researcher cannot limit the sample to the leaders of that organization, but must understand the perceptions of the reporters as well. Yet it must be considered that for every person allowed to speak, many others will be absent from the data collection. One cannot interview everyone.

These articulations of the epistemological nature of interviewing are important in delineating one's ultimate goals in the interview: collecting themes, deciphering motivations, and exploring concepts and dimensions in order to say something larger about some societal phenomena in the understanding of ongoing social practices. Lofland and Lofland (1995, p. 16) argued that in order to develop social theory: “(1) face-to-face interaction is the fullest condition of participating in the mind of another human being, and (2) . . . You must participate in the mind of another human being . . . to acquire societal knowledge.” Researchers must work to “enter the mind” of participants and informants in order to extract the knowledge and information around a particular topic of inquiry. Asking enough of the right kinds of questions will help to access the truth of the person (and to help the persons themselves know that truth). “Respondent interviews are a lens for viewing the interaction of an individual's internal states (social attitudes and motives) with the outer environment. The interview response is treated as a ‘report’ of that interaction” (Lindlof & Taylor, 2002, p. 175).

Interviews help us document and “know” historical events, societal tragedies, and triumphs, outcomes, predictions, and trends as well as allow us to understand how we live, who we are, and what we need for life fulfillment. In terms of media study, interviews can shed light on all of these experiences, situations, and relationships at all levels of production, the site of content and consumption. Examples of some research questions that interviews might illuminate include: How are digital technologies changing our perceptions of mediated time and space? How have concepts of “news” changed over time? How is Twitter changing power hierarchies in our society? How does childhood memory of the news coverage around national traumatic events influence our relationships with our children today? In-depth interviews that allow a participant to respond in context provide a rich documentation of these societal quagmires.

Once these questions of goal and sample are solidified, the interviewer can begin to make decisions about the kind of interviewing and analysis that need to take place. The remainder of this chapter explains how to exercise different approaches to interviewing in a pragmatic way.

Kinds of Interviews

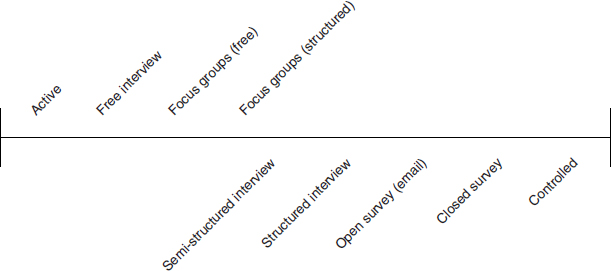

First, the interviewer chooses the interview tool: What type of interview is called for? The method and style of the interview follow the research questions, with consideration of the target population involved as well as the researchers' own limitations – resources, personality, and other constraints. Scholars of all disciplines have spent a lot of time classifying kinds of interviews according to how formal and standardized the interview template is, whether the response goal is measurement, and the amount of freedom the participant maintains (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995; Maccoby & Maccoby, 1954; Madge, 1965). Moser (1958) developed a continuum for interviewing that is a useful way to think about the types (as cited in Holstein & Gubrium, 1995; see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1 Functional interview continuum (adapted from Moser, 1958)

With Moser's adapted scaled typology as a guide, I shall explicate the interview types according to the level of control (or power) the interviewer exerts.

Active/Free

At the far end of the continuum, we have the “active” and “free” interview styles. Jack Douglas (1985) calls free-form techniques “creative interviewing.” This style of interviewing encourages the exploration of identity boundaries, of cognitive processing, of creative expression, of oral history, and other kinds of qualitative responding. “Interviews allow us to hear, if we will, the particular meanings of a language that both women and men use but that each translates differently” (Anderson & Jack, 1998, p. 65). No interview template is used; the subject and the interviewer simply talk. This style depends upon a rapport between researcher and participant, which must be built within the conversation. In this category we might also include the ethnographic interview (Lindlof & Taylor, 2002), the informal conversational interview (Patton, 1990) and the situational conversation (Schatzman & Strauss, 1973, p. 71) that can occur in the field. At this end of the continuum, the researcher and the participant share power equally for the direction of the interview.

Focus Groups

Both formal and informal, the group interview gathers a multitude of people to discuss a specific topic, text, problem, query, or phenomenon. Focus groups depend on a well-trained, directive moderator to help prevent groupthink, encourage all members to participate, keep the discussion on track, and otherwise insure the collecting of useful data (Fontana & Frey, 2008). Group interviews can be particularly useful when studying relational aspects of mediated engagement. Via group interviews, one can witness literal, real-time communicative processing as well as the hierarchal positioning that happens around some topics when discussed socially. Watching the power dynamics that arise in such interactions can be useful and fascinating.

Structured and Semi-Structured Interviews

These tend to be for one-on-one or with pairs of subjects. The “structure” of this refers to how strict the researcher needs to be with the protocol of questions. A structured template is one in which the researcher has a set of questions that must be asked, in the order laid out. This would be for those projects that need a more uniform response from participants. The much more ubiquitous semi-structured form provides a guide template for the researcher that allows for a more conversational approach to the exchange. Lindlof and Taylor (2002, p. 179) call this a “narrative” interview that results in a “dyadic interaction.”

Open/Closed Surveys

The use of open or closed surveying helps a sample clarify concepts, break down opinions, determine motivations, categorize attitudes, and also understand how people interpret their own motivations (Lazarsfeld, 1944). It is important to remember that the general survey represents people's perceptions as opposed to their actualities. The closed survey – that is, one where the items are close-ended or scaled – and the open survey where open-ended questions are employed both have the problem of self-reporting bias but can document important attitudes and habits; the survey is particularly popular among social sciences studying media.

Controlled

The most stringent of structured interviewing is called the “controlled” interview. Moser (1958, cited in Holstein & Gubrium, 1995) described this as an “interrogation.” He likened this style of interviewing to a police interview where the end objective is to derive a very specific answer.

Power concerns come into play at this stage of the design process as well, for how the template is structured and what style of technique is selected will determine the nature of the responses. As Camitta (1990, p. 26) wrote: “The interview, as a social genre that is controlled by the interviewer, is a form of mastery over object, acquisition of knowledge through control of language. Conversation, on the other hand, is more collaborative, depending upon affiliation rather than upon separation in its structure.”

Thus, the choice of interview style will be based on the research questions to be explored. For instance, a researcher interested in understanding a topic deeply but specifically might opt for some kind of one-on-one semi-structured interview style. Someone seeking to investigate relationships or identity might find the opportunity to witness the exchange of dialogue and information within a focus group particularly worthwhile. Ultimately, even the most free-form of interviewing must yield some kind of specificity for the researcher (otherwise, what's the point?) and the most controlling of styles will inevitably veer off script.

Institutional Review Board Approval

Once the study has been designed, the onerous process of the university institutional review board (IRB) must be navigated. This section relates most specifically to the research process within academic institutions in the United States, even though similar processes of organizational oversight certainly exist in other contexts and cultural environments. Many wring their hands and complain about IRBs across the nation, for the bureaucracy increased as institutions sought to protect study subjects and limit the liability when studies go bad. However, the training programs IRBs offer (or mandate) provide a useful opportunity, for budding and more advanced researchers alike, to reflect on the ethics of research.

The most important aspect of this process is to be as detailed as possible in answering the protocol questions without constraining future modifications (such as adding questions or even topics) to the study design. For example, researchers might consider increasing the anticipated number of study participants by about a third to allow for flexibility later on. The protocol offers a chance to consider whether or not you will identify your subjects and also whether you will deceive them: these will be key elements in the protocol approval. Many interview participants in media studies are not identified and not deceived (except in surveys that pair with experiments, but that is not the purview of this chapter). Most IRBs will want a viable confidentiality process for those participants, including a method for protecting and disposing of the transcripts and recordings collected. For those who wish to identify the participants, IRB will want to know the reason and be reassured that the information will not damage the person's reputation, livelihood, or life in any way. One alternative might be to name the person's organization – for example the New York Times – without identifying that person by name.

Some other tips related to the IRB process:

- The IRB process may take months. Beginning the process as soon as possible will help keep the data collection on schedule. Most IRBs post their meeting schedules and deadline on their websites.

- The administrator of the protocols can often be a great resource for understanding the best way to craft a successful protocol.

- Much can be gained from having an experienced person within the specific IRB look over the protocol before submission.

- Some universities will provide successful IRB protocols or samples of applications for researchers to model.

- At some schools, different boards (e.g., for education, social sciences, for medicine, etc.) govern different topics. For example, if you are studying how children communicate in schools, you might consider asking the educational division for a review of your protocol rather than your typical social science committee, as the education IRB would deal more frequently with research relating to children.

- Any future modifications to the study will require modifications to the protocol as well. Anticipating as many of those changes (such as more interviews with different populations, in different places, or with different questions) in the original protocol will save time later.

- Generally, any co-principal investigators and key personnel must have undergone any IRB training, which can take time.

- Often IRBs will offer different types of review, such as exempted, expedited, and full reviews. Exempted usually means the research involves information in the public realms, uses existing data, or otherwise offers minimal risk and does not need review by the board. Expedited reviews are typically for minor modifications or renewals of existing protocols or for those projects posing minimal risk. Everything else that involves interview subjects must usually go to full reviews in the academic settings. For example, my request to interview journalists about their attitudes on blogging was expedited because those comments are pretty formal in nature and don't pose any risk to journalists talking about this public realm issue. However, my protocol asking journalists about their news organization and attitudes about their jobs needed a full review because the board determined there was risk that the reporter as an employee might get into trouble with their bosses and so they wanted to insure proper confidentiality measures were in place.

Often scholars will be asked to answer questions, submit additional documentation, and make revisions during this process, which can take anywhere from a couple of weeks to months. It is important to keep in mind that IRB approval generally lasts for only a year and needs to be renewed and modified as the research develops. Also, because IRB members often cycle off in 1–3 years (depending on the university), researchers must periodically get reacquainted with the composition and particular philosophy of a new board.

Drawing a Sample

As we exist in “the interview society” (Silverman, 1993), researchers have the benefit of populations familiar not only with viewing interviews in the media but, most likely, with having been interviewed themselves. Yet, as with all the other aspects of the study design, the selection of the sample must be undertaken with care. Unlike quantitative surveys where the goal is to find as generalizable a sample of a particular population as possible, the qualitative in-depth interview must tap participants who will yield rich, thick responses that delve deep into some topic. As mentioned earlier, those who are privileged to speak hold great power to influence the resulting research and implications of the findings.

The selection of interview participants depends entirely on the ontological nature of the study, the proposed research questions, and the kind of method and style of interrogation chosen. For example, sampling can be “provisional,” “tentative,” and “spontaneous” in ethnography (Glaser & Strauss, 1967/2009), which means that a researcher chooses participants according to the flow of the ethnographic encounter and not according to some rigid typology. For structured templates that seek to draw out the very specific situated knowledge of a particular group, the sample must be targeted and focused. Each person's capacity for answering the questions honestly and thoroughly must be weighed during the sample selection (Mason, 2002). This is not to say that people who might be inarticulate or otherwise need help to understand how they want to answer should be excluded, only that those possibilities should be considered when choosing whom to interview, the length of time needed for the interview, and the structure of the questions.

Other notes on sampling:

- How many people is “enough”? I have seen viable studies that interrogated just a handful of people and then others with hundreds. Generally speaking, studies need enough people to achieve saturation (that is, the point at which you know what the person is going to say before they say it because you have heard it from enough other people). Research questions should guide the sample. For example, if your question has to do with how female publishers deal with gender power dynamics in the news industry, you could interview just a handful of women publishers because so few of them exist. However, if you want to know how reporters investigate politics, then you would want to talk to as many political reporters as you can – I would suggest at least a dozen, but 25 or more would be ideal. Expect the interview to take 30 minutes to two hours. The optimal size for a focus group is 6–12 people, and each session tends to be about 90 minutes in length (Lindlof & Taylor, 2002, p. 182).

- Recruitment strategies determine the composition of the sample. If, say, you want a general population in a local town, then you will want to attract people in a variety of methods: not just by taking an ad out in the local paper or media organizations (which will garner older, educated, middle-class adults) but also by soliciting people in public spaces such as parks or farmers' markets and via the snowball technique (asking subjects for other names), and by appealing to community and school listserves, among other places.

- Lofland and Lofland (1995) recommend that researchers sample from a population that they themselves are part of, that is, “starting where you are.” If you have a hobby or interest in a particular area, Lofland and Lofland suggest you draw upon that background of knowledge. For example, if a researcher has been a reporter or producer in the past, he or she could refer to that content production lexicon or use network techniques from that industry when interviewing that population. This could allow for better access and gain greater trust from informants.

- Offering incentives for research participation can encourage a more inclusive sample. For example, students often receive credit for courses. Other popular rewards include payment, reimbursement of mileage, coffee or lunch, and entry into a raffle for some prize.

- Soliciting subjects and gathering contact information at events is a great way to draw a sample (though interviewing people at the event for research purposes raises problems of sound and distraction).

- The parameters of the interview, such as length and confidentiality, should be clearly communicated. The last thing a researcher wants is to promise a 20 minute meeting, knowing the interview will take an hour, and then have the subject leave.

Developing Questions

Interviewing is about being aware that “(1) actions, things and events are accompanied by subjective emotional experience that gives them meaning; (2) some of the feelings uncovered may exceed the boundaries of acceptable or expected female behavior; and (3) individuals can and must explain what they mean in their own terms” (Anderson & Jack, 1998, p. 169). These researchers were discussing gender issues within interviewing, but the point can be generalized. The interview template should help the subject access those perceptions and experiences in an articulate manner. Most researchers agree that interviewing involves “the construction or reconstruction of knowledge more than the excavation of it” (Mason, 2002). They suggest that every interview is a representation of an interaction between interviewer and interviewee as well as about the pure gathering of information. With this in mind, question development for the interview should be a flexible act that can morph not only from participant to participant but also within the interview itself. The interview could be considered as a living thing that can be quelled or propelled forward with just the right question – or even just the right amount of silence or subtle gesture. And yet, though the goal of every interview will always be to record a “dynamic unfolding of the subject's viewpoint” (Anderson & Jack, 1998, p. 169), the interview process must always be activated within the context of the ultimate aim of the research: How do I ask questions so I have the necessary information to answer my research questions? I like to think of my template as keeping the subjects on a narrative course that unveils situated knowledge in an ordered manner.

Often my students complain that their interview participants declined to fully answer their questions, responded in monosyllables, or otherwise provided only superficial information. They were not getting “anything good”! The tone and the framing of every question matters as well as the order in which it is asked (Anderson & Jack, 1998). Even facial expression and body language will change how a person answers, in addition to what the conversation was like before the question was posed. If you change the topic with a new question too early in a person's recounting, you set boundaries for the interviewee, who will limit or expand on his or her next answer accordingly. The respondents' past experiences, position, gender, race, age, and so on should be considered when selecting question strategies. Each template might incorporate a variety of strategies, such as nondirective (“Describe your experiences . . . ”), directive (“Please compare X to Y”), the use of a common lexicon, requests for anecdotes and examples, and the posing of hypotheticals. The right tone and question structure will depend on the situation, the participant (and the participant's experience), and how specific you need them to be. Statement making on the part of the interviewer can be off-putting. Gender and race can cause people to enter the conversation with predetermined judgments about your motivations. Allowing extra time at the beginning of the interview can help participants feel at ease about your intentions.

Other tips include the following:

- Follow-up questions are key to arriving at a complete answer. Most people will not understand the full dynamics or implications of the posed question, or they will use the first response to “work out” what they really want to say.

- When asking questions, the interviewer might refer to current events and situations as a way to demonstrate appropriate knowledge of the background and context. This helps build credibility with participants.

- Recorded pre-interviews can cue the researcher to being alert to leading questions and an aggressive tone.

- Jargon, loaded terms, or academic language in questions can confuse participants.

- Allow silence to encourage elaboration.

- Many of my participants ask me for a list of the questions I am going to give them. I provide them with a generalized template but resist giving them an entire blueprint. I stress to them that the interview will range and that I will follow up on their answers. Still, being able to contemplate their answers makes some people feel less nervous, and I accommodate them as far as my research purpose allows.

Collecting the Data

Data collection entails the interview itself, which can last anywhere from half an hour to several hours, as well as the filing of the audio recording and the transcript. I begin each interview by informally chatting and then discussing the study and what I am hoping to accomplish. I always stress the applied research part of my intention, as people like to feel that they are contributing to a greater cause. We generally have a conversation that I do not record about some topic that is similar to but not exactly like the interview itself as a kind of warm-up. I buy them coffee and let them get settled. I give them an opportunity to get used to whatever recording devices I have on the table. I explain to them that I want them to be completely honest with me and to let me know if something I am asking makes them uncomfortable. I talk to them about how they can end the interview at any moment and can withdraw their participation at any time, even after the interview has been completed. I can see them visibly relax when I say this.

The modes of interviewing I use include face-to-face interviews (either group or individual), phone, letters, Skype, iChat, and email. Each has its benefits and negatives. I prefer face-to-face interviews because I can see immediately how the person is reacting to my question, tone, gestures, and so on. I have also used phone chats, which work well because the person is somewhere they are quite comfortable and does not see my recording devices; they can often forget that it is a researcher on the other end. Also phone interviews allow me to contact people who may not live near me. Skype and iChats are similar to phone interviews (though Skype especially can be glitchy). Bird (2003) elected to interview via both letters/email and phone, though both methods have been criticized as being ineffective, abbreviated, and lacking in intimacy (Babbie, 1989; Bird, 2003; Chadwick, Bahr, & Albrecht, 1984). Rather, Bird found intriguing differences: where women wrote long, emotional letters to her questions and spoke intimately on the phone, men kept their responses in both media more brief and businesslike. She wrote of her methodological experience:

I am not suggesting some kind of blanket advocacy of phone interviews or letters for women . . . Businesswomen who use the phone all day at work may not relish the thought of a long phone interview. Those who write a lot at work may see writing letters as a chore, while those who have literacy problems might view a request to write as a threat or embarrassment . . . All methodological approaches are characterized by constraints; the key is to be flexible . . . and be aware of the possible impact of methodological choices. (Bird, 2003, p. 15)

She and other researchers suggested that the particular mode of communication will affect the power dynamics innate in the exchange of data. For example, a phone interview will mitigate some of the power dynamics by removing the social pressure of appearance (Bird, 2003, p. 15). In contrast, I have found that in email interviews (which all my students are eager to do), participants take advantage of the absence of that social pressure and dominate the exchange such that the researcher may not achieve the saturation he or she desires. In effect, the researcher loses power (and that's not good either). Email responses are often truncated and superficial, followups are difficult to enact, and difficult questions are sometimes skipped altogether.

When the interview has commenced, the researcher must not only record the voice, ask the questions, and take notes, but also observe what Gorden (1980, p. 335) describes as four modes of nonverbal techniques: proxemics (use of interpersonal space to communicate attitudes), chronemics (the use of pacing of speech and silence), kinesics (body movements or postures), and the paralinguistic (variations in tone, pitch and quality of voice). The interaction, understood and considered in a holistic manner, must be noted and analyzed (Anderson & Jack, 1998).

Indeed, social convention binds all of our interview participants, each of whom embodies multifarious life experiences that color all their responses (Anderson & Jack, 1998). In other words, is the woman speaking as the daughter of someone who spent every morning sharing the newspaper at the breakfast table (e.g., tinged with the interpersonal experience of the mother–daughter relationship) or as a mother herself (thinking of her desire for her own children to be informed citizens)? She activates different parts of her experience depending on her mood (as well as what happened most recently, e.g., a good day, a fight). Furthermore, those life experiences will leak into all of her responses and form a reaction to you, your gender, your dress, and your body language. For example, a woman will respond to a male interviewer differently from a female one as “gender filters knowledge” (Denzin, 1989, p. 116). Similarly, participants must be allowed to switch voices (i.e., they might move out of the category to which you have assigned them) and also contradict themselves. I find that my participants sometimes like to “try out” an answer before giving their real response.

One strategy for beginning to organize the prolific amounts of data the project will generate is what I will call a “pre-memo.” A pre-memo is essentially a series of comments that the researcher makes while reviewing the interview transcript immediately after the data collection. I say after the data collection, but I really consider this to be part of the data collection because this pre-memoing should occur in conjunction with the interview itself. The pre-memo is not the same thing as a formal “memo” in the Strauss and Corbin grounded theory tradition (see the next section for more on that). Rather it is a chance for the interviewer to make a note of all the gesturing and emphases the participant imparted that were not recorded and a chance to make more general observations about what was said. For example, a pre-memo might include notes about how to ask the question differently the next time or a reminder that another interview subject has said something similar. I am very informal in these pre-memos, as they are only for my eyes. I will often comment upon what I have heard, its credibility, for example, or its resonance with what others have said or simply add context to whatever was said, such as “Her comments on the media coverage here came the day after a big controversy involving a local reporter and the campaign.” Knowing I will be doing pre-memos helps me to put aside the process of analyzing during the process of listening (Anderson & Jack, 1998).

Other notes on collecting data include:

- First and foremost, the interview participant should sign the informed consent form with the IRB approval mark, if one needs to be completed.

- Where the interview takes place matters: a loud coffee shop or the person's home? In part, this depends on what will be discussed: sensitive material is probably best exchanged in a more private place.

- Audio recordings of interviews – with transcription – provide the evidence and must be made in order to have a record of the data. I recommend taking notes as well. I like to use my laptop, but some subjects will feel uncomfortable with a machine between you and them. The computer and the tapping of the keys interrupt the interchange, and thus the intimacy. If you are interviewing in person, you can usually tell right away if the interviewee is distracted by your recording devices based on his or her furtive glances at the machine and halting answers. I suggest using a banana-clip lavalier as a microphone and then moving the recorder to your bag. Another option is use your mobile phone as a recording device, which can be less obtrusive for some people.

- Pre-interviewing for demographic data can save time. The person's age, income, education, and other information will allow for a comprehensive characterization of the sample in the methods sections later on.

- Signs of confusion, reluctance, ambiguity, and contradiction should all be noted in context. Silence might indicate interesting intersections between culture, ideology, and social roles (or it could just mean they are choking on a cookie).

- Follow-up questions should not shut down the flow of the conversation.

- If the person suddenly tells you he or she must leave early, skip immediately to the most important questions and ask if you can either meet again or send follow-up questions in an email.

- Sometimes my participants will ask to see any article before publication. I tend to acquiesce. If the person wants to change his or her comment, I consider that to be an important action; often the desire to self-censor is an important data point. This is, after all, not journalism. The main goal here is to make sure the person's thoughts and perceptions are taken down accurately. Occasionally a researcher's subject matter or a person's desire to completely change what was said will make this an awkward request. At that point, the researcher may consider dropping the participant from the study or negotiating the meaning of the evidence until he or she is appeased.

- It is best to avoid applying existing schema and biases to what you might hear.

Analyzing and Writing the Data

The words of the participants in the interview project represent the units of analysis. The researcher should have an analytical tool in mind as he or she approaches this raw data. First, he or she must consider which analytical technique makes the most sense: a deductive approach such as grounded theory, or an inductive approach such as a specific theoretical framework. Discourse analytic techniques will enable a researcher to explicate how knowledge concerning the topic at hand is narratively constructed (see Fairclough, 2003; van Dijk, 1985, 1993). Discourse analysis is particularly useful because it can help uncover the power, social, cultural, and other relationships at work in the person's construction of dialogue. As the researcher sets out to analyze the interview transcripts, he or she must explore three significant relationships within the text, according to Anderson and Jack (1998): (1) the linguistic or performative aspects of an interview; (2) the individual connectors; and (3) the interview data as situated in a social historical consciousness. This is done by: “(1) listening to the narrator's moral language; (2) attending to the meta-statements; [and] (3) observing the logic of the narrative” (Anderson & Jack, 1998, p. 169). The “moral language” refers to the participant's value system as revealed by the choices of phrasing and other dialogic classifications that indicate a person's identity paradigm.

Meta-statements alert us to the individual's awareness of a discrepancy within the self – or between what is expected and what is said. They inform the interviewer about what categories the individual is using to monitor her thoughts, and allow observation about how the person socializes her feelings or thoughts according to certain norms. (Anderson & Jack, 1998, p. 168)

The final key in any analytical experience is to discover the patterns, recurring themes, and narrative links among this moral language and the metastatements – or “observing the logic of the narrative.” The connections made during this exploration of the “narrative logic” will reveal the underlying meaning in relation to theory. This process is the essence of discourse analysis but is also very similar to grounded theory analysis as described by Strauss and Corbin (1998).2 For Strauss and Corbin, the researcher conducts a three-pronged analysis called open, axial, and selective coding. Open coding involves the initial read through of the text that identifies general concepts, their properties and dimensions. In axial coding, the researcher reviews the texts again with the concepts to link categories and reveal thematic patterns between the concepts. Finally, selective coding helps a researcher establish the theoretical implications for the patterns discovered.

Every person's context and experience must be considered as an analysis unfolds. This can be done in the analytical “memo” and diagram, which Strauss and Corbin (1990) insist upon.

Writing theoretical memos is an integral part of doing grounded theory. Since the analyst cannot readily keep track of all the categories, properties, hypotheses, and generative questions that evolve from the analytical process, there must be a system for doing so. The use of memos constitutes such a system. Memos are not simply “ideas.” They are involved in the formulation and revision of theory during the research process. (Strauss & Corbin, 1990, p. 10)

I am a big believer in the analytical memo (text) and diagram (which is basically a visual memo) as it forces the researcher to engage actively with the material, to find connections that might have been missed through a mere interpretive analysis, and to think more conceptually about the data.3 The written memo can consist of a comment next to a piece of evidence (i.e., the participant's words) as short as a word or phrase such as the name of a emergent theme (“connotes freedom of the press”) or a theoretical note as long as an essay. I often draw directly from my memos for my resulting papers, and thus consider this process a form of draft writing. The diagram can help formulate the connection between concepts in a more structured manner, but can also depict the relationships or flow or directionality being revealed in the evidence. As Strauss and Corbin point out, however, each researcher must formulate his or her own “style and technique” (1990, p. 223) of memoing, diagramming, and, ultimately, of analysis.

Some other tips as you analyze:

- Alternative validities always exist. Any discrepancies in the conversations can make for wonderful richness and complexity.

- Noting significant passages of text and identifying the number of the participant during analysis will aid the writing process later on, particularly if the final manuscript requires quotations from the evidence.

- Consider using a computer software program to help organize the data. Each transcript must be cleaned and standardized, and then a program such as NVivo can help you code for themes, search for keywords, diagram, and develop matrices of parallel concepts.

- A return to those original research questions once the analysis is finished will solidify any findings. Have those questions been answered with this evidence? I will often take a legal pad and write each original research question on its own sheet and then read through all my data again, making notes and writing down macro points I see as I go. This kind of brainstorming ultimately informs and supplements my discourse analysis (or selective coding).

- Wolcott (1990) suggests beginning the writing process even before data collection in order to crystallize the research questions, any theoretical framework, and the ultimate goals of the project.

- Consider sending your informants your finished article before publication for verification of contextualization.

Conclusion

I hesitate to bring all of this to any conclusion, given what Wolcott (1990, p. 55) cautioned about: the “grand flourish that might tempt me beyond the boundaries of the material I have been presenting.” Yet I do want to reiterate the importance of the interview as a methodological tool to uncover the meaning in some communicative puzzle. Where surveys can produce a broad and generalized documentation of a population's habits and attitudes, the in-depth interview – however it is structured – can investigate those superficial statements. The interview can delve into hidden meanings, explore identity and other constructions, and reveal relationships the person has not only with media but also with others who influence that media usage. However, as this chapter has tried to demonstrate, the interview's power dynamics will shape what is said. Researchers can attune to these power issues by being transparent, self-aware, and sensitive to the biases and inhibitions that might be present.

Historically the interview has been described as both an art and a science such that no one formula will ever suffice, nor will two interviews ever be the same. It is important to note that generalization tends not to be the goal in this technique, but rather the interview offers an exercise in human interaction, a study in relationships and meaning construction, and an examination of the social processes and forces at work in culture, economics, politics, and other aspects of society. This chapter has attempted to iterate the logistics of the science of interviewing while maintaining that the very serendipity, magic, and creativity of “interview as art” might be exactly the reason the in-depth interview should be performed. The ability to so closely investigate someone's motivations or attitudes – particularly in regard to media studies – can reveal so much about the incredible variety of roles that media and other phenomena play in our lives.

NOTES

1 This is not a problem specific to interviewing, but one that confronts all methodologies.

2 There are many, many ways to conduct grounded theory. I like Strauss and Corbin's 1998 version because it offers such a blueprint for researchers. But some might prefer something without such rigidity.

3 For more on memoing and diagramming, I highly recommend the description in Strauss and Corbin, 1998, chap. 14.

REFERENCES

Anderson, K., & Jack, D. (1998). Learning to listen: Interview techniques and analysis. In R. Perks & A. Thomson (Eds.), The oral history reader (pp. 157–171). New York, NY: Routledge,.

Babbie, E. (1989). The practice of social research. New York, NY: Wadsworth.

Bird, E. (2003). The audience in everyday life: Living in a media world. New York, NY: Routledge.

Brenner, M. (1981). Social method and social life. London, UK: Academic Press

Camitta, M. (1990). Gender and method in folklore fieldwork. Southern Folklore, 47(1), 21–31.

Chadwick, B., Bahr, H., & Albrecht, S. (1984). Social science research methods. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Cicourel, A. V. (1964). Method and measurement in sociology. New York, NY: Free Press.

Converse, J. M. (1987). Survey research in the United States: Roots and emergence, 1890–1960. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Denzin, N. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Denzin, N. (1989). Interpretive interactionism. London, UK: Sage.

Douglas, J. (1985). Creative interviewing. London, UK: Sage.

Elliott, J. (2005). Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London, UK: Sage.

Fontana, A., & Frey, J. (2008). The interview: From neutral stance to political involvement. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (pp. 115 –160). London, UK: Sage.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967/2009). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. New York, NY: Aldine Transaction.

Gorden, R. I. (1980). Interview strategy techniques and tactics. Homewood, IL: Dorsey.

Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. A. (1998). Narrative practice and the coherence of personal stories. Sociological Quarterly, 39(1), 163–187.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analyzing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London, UK: Routledge.

Fontana, A., & Prokos, A. H. (2007). The interview: From formal to postmodern. New York, NY: Left Coast.

Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. London, UK: Sage.

Lazarsfeld, P. F. (1944). The controversy over detailed interviews–an offer for negotiation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 8, 38–60.

Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2002). Qualitative communication research methods. London, UK: Sage.

Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. (1995). Analyzing social settings: A guide to qualitative observation and analysis. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Maccoby, E. E., & Maccoby, N. (1954). The interview: A tool of social science. In G. Lindzey (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology. Vol. 1: Theory and method (pp. 449–487). Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Madge, J. (1965). The tools of social science. Garden City, NJ: Anchor.

Mason, J. (2002). Qualitative research. London, UK: Sage.

Moser, C. A. (1958). Survey methods in social investigation. London, UK: Heinemann.

Oakley, A. (1981). Interviewing is like a marriage: Interviewing women: A contradiction in terms. In H. Roberts (Ed.), Doing feminist research (pp. 30–61). London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluations research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pool, I. de S. (1957). A critique of twentieth anniversary issue. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), 190–198.

Schatzman, L., & Strauss, A. (1973). Field research: Strategies for a natural sociology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Silverman, D. (1993). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods of analysing talk, text and interaction. London, UK: Sage.

Silverman, D. (2000). Interpreting qualitative data. London, UK: Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (1st ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

van Dijk, T. A. (1985). Handbook of discourse analysis: Discourse and dialogue. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

van Dijk, T. A. (1993). Principles of critical discourse analysis. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 249–283.

Vidich, A. J., & Lyman, S. A. (2003). Qualitative methods: Their history in sociology and anthropology. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research: Theories and issues. (pp. 55–130). London, UK: Sage.

Wolcott, H. F. (1990). Writing up qualitative research. London, UK: Sage.