6

Music in the New Capitalism

ABSTRACT

This chapter attempts to reinstate capitalism as the transcendent category of analysis for music production. This new capitalism is marked by the ascendance of the new petite bourgeoisie. This class promulgates an ideology of the hip and the cool and has an outsized role in the production of culture, since most musicians today are forced to permit their music to be used in commercials. The new class is comprised of new kinds of cultural workers, who can deploy their taste as music supervisors, choosing music for film and broadcasting in an era when more music is more easily available. Another aspect of the new capitalism is that workers can be compensated less, or not at all. In the realm of advertising composition is increasingly outsourced, as it simple to upload video to servers around the world. Users enter data on songs in online databases and their search habits are recorded and used to sell more products, all without compensation.

Introduction

Much of my work has been concerned with attempting to apprehend the present moment – a moment that has been characterized in many ways in the couple of decades to which I paid attention: postmodern, late capitalist, a network society, an information age, an era of globalization, neoliberalism – and many more things. It has long seemed to me, however, that the primary category ought to have something to do with capitalism, not in a vulgar Marxist sense of the economic base “determining” a (cultural) “superstructure,” but in the sense of capitalism as a social form that profoundly shapes people's relationships to each other.

I am thus advocating that we attend both to capitalism and to culture and that we see how one inflects and influences the other. This is by now a rather familiar combination of Marxist and Weberian perspectives; but it is, unfortunately, remarkable that neither component has had much impact on the study of music, which remains overly wedded to positivistic, and thus ahistorical and acultural, modes of analysis. There are, however, some exceptions – for instance the work of Steven Feld, Charles Keil, and Anthony Seeger, all of whom, I should note, were not trained as ethno-musicologists but as anthropologists (for some of the few explicitly Marxist books in music studies, see Keil & Feld, 1994; Qureshi, 2002; Seeger, 2004).

What I want to do in this chapter is to attempt to bring together some of the themes I have been exploring for many years, but under the rubric of the study of capitalism: new capitalism, which was facilitated by neoliberal ideologies and by new communications technologies, and which has a global effect. Undue focus on these (or other) elements as aspects of the new capitalism has tended to obscure the longterm workings of capitalism as a historical economic system and as a social form.

Thus it is my goal here to attempt to reinstate capitalism as a transcendent category of analysis; and I propose to do this by way of understanding what was going on in the recent past (and carried over into the present) as part of long-term processes, which are rooted in the economic and in the social and are not unique either to the present or to the recent past, as so many studies seem to assume. What follows is, in part, a rehearsal of some of the issues I have written about in the past, but also an attempt to bring them together under this broader framework, which was not always present in some of my earlier publications.

The New Capitalism

I borrow the phrase “new capitalism” from Richard Sennett, who has analyzed the social and cultural effects of this phenomenon in a couple of recent books (Sennett, 1998, 2006). Sennett is concerned with the cultural effects of the new capitalism, but I will begin here with a discussion of historical, economic, and political factors.

While there has generally been a dearth of writings focusing on capitalism in recent years, it must be acknowledged that scholars writing from Marxian perspectives have continued to study it. Probably the first major salvo in attempting to understand the new capitalism was Ernest Mandel's often cited (though, I suspect, little read) book from 1972, Late Capitalism (Mandel, 1978). For many readers, this book was brought to attention by Fredric Jameson in his influential “Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” (Jameson, 1984). References to Mandel were few, but Jameson's endorsement mattered. Nonetheless Mandel's writing, given its technical nature and its engagement with a long history of Marxist arguments about capitalism, was ultimately less influential than Jameson's article.

Yet there are aspects of Mandel's book that continue to be useful. Such is his periodization of capitalism into three historical phases: “competitive capitalism,” from the onset of the Industrial Revolution until about 1880; “imperialism,” which lasted until the end of World War II; and what he called “late capitalism.” This current phase is marked by the declining importance of the state; the monopolistic and oligopolistic pursuit of massive profits and its global growth; the increased concentration of capital in huge corporations; the defeat or decline of labor and other kinds of oppositional movements; the globalization of financial capital; the rise of new, transformative technologies such as the personal computer; an economy increasingly dependent on the defense industry; the growth of debt; new forms of colonialism; an increasing polarization of wealth; heightened consumption – and still more, at least according to some scholars.

But Mandel's book proved to be less influential than it might have been without the author's engagement with sometimes arcane aspects of Marxist theory. Other books appeared in the 1980s and early 1990s that continued to wrestle with what was widely perceived as the changing nature of Western capitalism, in particular those of Scott Lash and John Urry (1994) and of David Harvey (1989). Lash and Urry noted the rise of global corporations with an international division of labor; the separation of finance from industry; the growth of industry in small communities and rural areas; the transmission of information and knowledge electronically rather than through print; in the social sphere, a movement out of the cites and toward the suburbs; the pursuit of increasingly narrowly defined interests; and new kinds of social groups, such as the new bourgeoisie (see also Bourdieu, 1984). Harvey, for his part, made much of the “flexible accumulation” – a post-Fordist type of industrial production, of which he says that it is “marked by a direct confrontation with the rigidities of Fordism,” resting as it does on “flexibility with respect to labour processes, labour markets, products, and patterns of consumption” (Harvey, 1989, p. 147).

Some authors have have argued that new capitalism relies heavily on the production of culture. Lash and Urry, early articulators of this position, noted in 1994 how “economic and symbolic processes are more than ever interlaced and interarticulated; that is, that the economy is increasingly culturally inflected and that culture is more and more economically inflected” (Lash & Urry, 1994, p. 64). Subsequent authors have pursued much the same line (e.g., Scott, 2008). Additionally, as the production of culture has changed, so has the culture of production (see Boltanski & Chiapello, 2005). The production of culture is driven also by an ideology of the hip and the cool, as I will discuss below. This ideology is related to the facts captured by Richard Sennett when he argues that the new capitalism is marked by pervasive ageism, which is driven by more than economic factors: younger workers might already have technical knowledge that older workers would acquire only if they were retrained; younger workers cost less; and so on. Sennett also discusses the increased importance of the notion of “talent” (or, as my own research has revealed, “creativity”: Taylor, 2012).

I think that part of the reason why capitalism fell off the radar screen is the increasing “humanitization” of the softer social sciences, which came in with the cultural studies boom of the 1980s. It was striking to see how Jameson's influence was filtered into subsequent publications, with all the Mandel-derived thinking excised from it and with postmodernism reduced to a list of traits or characteristics such as “depth-lessness,” “waning of affect,” or “pastiche.” The predictable effect was a seemingly ever-expanding number of lists with an equally expanding number of terms, as I have written elsewhere (Taylor, 2002). Postmodern culture registered the effects of late capitalism, which was largely ignored by many scholars, unanalyzed.

Writings that did place capitalism at the center of their analyses have slowed to a trickle in the last couple of decades. Many recent books have been concerned much more with other phenomena of the present or of the recent past – such as the advent of new digital technologies, which made people increasingly interconnected, in a “network society” (as Manuel Castells, 1996 calls it); or, as we have seen, globalization and neoliberalism. But in these writings capitalism tended to take a backseat to the new technologies or to their effects: capitalism was simply assumed to be, or interpreted as, an effect more than a cause. In what follows I will address the questions of globalization, networks, and neoliberalism not as singular developments, but as salient characteristics of the new capitalism.

Music in a Neoliberal World

Let me start with the question of neoliberalism. Neoliberal policies predate what we have come to think of as “globalization” and the interconnected world, though this world couldn't begin to be as fully realized as it has been recently until the rise of new communications technologies, which I will consider in the next section.

Even though “in a general way,” as Pierre Bourdieu writes (1998, p. 34), “neo-liberalism is a very smart and very modern repackaging of the oldest ideas of the oldest capitalists,” it is important to remember that one cannot understand capitalism simply in terms of the “economic logic of capital and its accumulation” (Foucault, 2008, p. 164). Capitalism must instead be understood by examining specific economic–institutional formations, which vary historically and geographically. Neoliberalism is a particular economic–institutional formation of the so-called developed countries, and its US form is particularly virulent (see Klein, 2008).

By “neoliberalism” I mean to refer to the body of ideologies that originated in the 1950s and really gained traction in the 1980s, being facilitated by the rise of new communications technologies.1 These ideologies advocated deregulation, privatization, the withdrawal of the state from many of its former responsibilities to its citizens, and, in general, “the insertion of the ideologies of enterprise and competition into all aspects of economic and social management” (Flew, 2009, p. 6). Neoliberalism advocates the working of the private sector over the public and relies on the wisdom of the markets; it emphasizes a kind of hyperindividualism by wielding ideologies of consumer choice and by fostering what has become known as the “care of the self.”

Foucault observes that neoliberalism in the US is not “just an economic and political choice formed and formulated by those who govern and within the governmental milieu” (Foucault, 2008, p. 218). It is, rather, “a whole way of being and thinking. It is a type of relation between the governors and the governed much more than a technique of governors with regard to the governed” (ibid.).

Neoliberal policies and practices have dramatically altered the landscape of the production of music in the US. Record labels and other entities that produce music, such as advertising agencies and music production companies, were bought and sold at unprecedented rates; the legendary adman Bill Backer told me that advertising agencies became “pawns in a Wall Street game of mergers and acquisitions” (Backer, 2004). Many of the people I interviewed for my project on music and advertising (Taylor, in press) spoke negatively of the changes that came to their industry in the 1980s, when budgets were reduced, music was increasingly tested on focus groups, and the bottom line became all important.

The increased interest in profit has meant that the music industry – and the culture industries more generally – have sought to find the next blockbuster rather than nurturing a number of artists or projects, in the hopes that one or two might become successful, and using that success to subsidize the other artists or projects. With the rise of new technologies that increased the cost of production, it became much more efficient to produce one blockbuster than a series of recordings by various musicians, in the hopes that one might make it big.

Newer technologies have also made it possible for musicians to produce high-quality recordings of their own music in their own studios. The difficult part for them has come to be not so much the production of their own music or its distribution, which can be easily accomplished online now, but getting the word out, marketing. The major record labels have become increasingly more marketing than recording companies, since this is the one remaining function that is beyond the capabilities of musicians. A band can erect a website, but this is not the same thing as spending thousands – or millions, in the case of major releases and of many films today – on marketing (see Lash & Urry, 1994).

Probably the most significant policy shift in the last couple of decades has been the passage of the Communications Act of 1996, which allowed a single entity to own more than one radio station in the same city and in the same market. The result has been an utterly predictable trend toward monopolization. Only a decade after the passage of the law, the top four radio station owners broadcast to almost a half of all listeners, and the top ten owners broadcast to almost two thirds of the listeners (DiCola, 2006). As a result, playlists have been streamlined, since it is cheaper and more efficient to play the same songs repeatedly at every station owned by a single company than to attempt to locate a broader spectrum of songs to air, or to permit disc jockeys (DJs) to select them.

One profound effect of this situation has been to break down – remarkably quickly – many musicians' resistance to permitting their music to be used in commercials. For decades, musicians desiring to preserve the appearance of independence from commercial processes refused to allow commercial uses of their music; but this position began to weaken, especially for younger musicians, when it became increasingly difficult to achieve radio airplay.

And, as the culture industries (in which I include not just the traditional industries of film, television, music, and so on, but also advertising and marketing) increasingly target youth and increasingly seek to discover – or create – what is the hippest, coolest product around (until the next one, tomorrow or the day after), these industries have become increasingly ageist, as many have written (see Nixon, 2003; Sennett, 1998), signaling a more general destabilization for many workers more generally. Barbara Ehrenreich's “fear of falling” (Ehrenreich, 1989) – the fear of losing middle-class status – is increasingly becoming the fear of falling and never rising again, or even of never rising at all, as the polarization of wealth that began in the 1980s escalates. Douglas Coupland has coined a new phrase to describe this phenomenon: “blank-collar workers,” “formerly middle-class workers who will never be middle class again and who will never come to terms with that” (Coupland, 2010, §A, p. 29).

Another aspect of the world of neoliberal capitalism is that labor has become cheaper or, in some cases, free; cheaper in the sense that, in some areas of the culture industries, people have been terminated and rehired on a freelance basis, which means that they receive no benefits. (In a country such as the US, which is increasingly changing into a Third World state with a massive gap between rich and poor and in which social programs lag far behind those in Europe, the absence of a good healthcare plan or retirement plan is an extremely serious issue.)

Free labor is made possible by companies' reliance on the World Wide Web to gather information on consumers' tastes and purchasing habits. Many years ago, Dallas Smythe wrote a provocative article about what constituted the commodity in broadcasting and concluded that it was the audience (Smythe, 1977). This article received some attention at the time of its publication, but it hasn't been much considered since (see, however, Newman, 2004; Taylor, in press). Yet Smythe's main point is still worthy of consideration. Advertisers and advertising agencies guarantee the attention of a certain demographic group of viewers at certain times and in certain places, to advertisers who seek to purchase that attention. Therefore, Smythe concluded, the commodity in broadcasting is not the program, nor the goods advertised on it, but the audience itself.

This seems straightforward enough, and most US viewers know it already: a favorite program could be cancelled, since the viewership wasn't large enough to permit charging sufficient fees to make airing the program profitable. But if we fast-forward to the present and to the World Wide Web, we find the surfers' time being harnessed in new ways, and not simply by being spent on websites that are supported by advertisements. If one patronizes a commercial website such as amazon.com, which garners information about consumer tastes in order to target these consumers and others with similar tastes more efficiently, then can we not consider these consumers' time to be uncompensated labor?

Or take another example: websites such as Netflix collect viewers' film-rental habits in order to make recommendations to future patrons. Uncompensated labor, too.

Or, if one purchases a new compact disc (CD) – a dwindling number of people, admittedly – and one happens to be the first to play that disc in iTunes, one can enter information on the compact disc that will then be made available, via a central database, to anyone who inserts the same recording. More unpaid labor. In fact, it seems to be a point of pride for some that they were the first to enter the information for a particular recording.

Perhaps this is all a form of generalized exchange à la Lévi-Strauss (1969), since any individual user can benefit from another's labor. But this is generalized exchange with strangers on a massive, global scale, strangers in separate commodity cultures networked around the world. Relying on informationalized and databased consumer tastes is one thing. With the rise of new communications and other technologies that made the proliferation of musics from around the world common – or perhaps I should say musics from around the world more common in the West, since the West's musics had been recorded and distributed almost since the beginning of recording in the late nineteenth century – new positions emerged that helped viewers, listeners, and others navigate their way through this plenitude of music.

Awareness of the necessity of such guides emerged with the massive success of the film The Big Chill in 1983 and its accompanying soundtrack. People in the music industry realized not only that marketing with music to baby boomers could be lucrative, but that the people who choose music for such albums – music supervisors – could be treated as important advisors. In broadcasting and advertising, the rise of the music supervisor has been an important recent development.

The music supervisor is a kind of cultural intermediary who has emerged in this economy: the person who is good at sniffing things out. It is the music supervisor's job to seek pre-recorded music for use in film and in broadcasting. This practice has become so common now that many US television programs conclude with a few minutes of a song, without dialogue. Television-program websites list songs played for curious listeners; CD compilations of songs from television programs can (or could) sell hundreds of thousands of copies. Music supervisors have largely replaced radio DJs as the humans choosing the music they hear (to the extent that radio stations with DJs who choose their own music tout the fact that the station plays “hand-picked music,” as a local station here in Los Angeles claims).

According to one music supervisor,

What will work for me and my film will also work for those artists in their careers. Obtaining a film placement or a television placement is a very valuable and positive step in a live musician's career. It's kind of like what getting on the radio meant in 1955. [. . .]

[A] lot of [television] shows are music driven. A huge percentage of the people who are of record-buying age buy their music based on what they've seen on television. The people who are selecting music for television shows are trusted; their taste is trusted by the watchers of those shows. So in a weird twist of fate, I am able to function in much the same way that, say, Wolfman Jack did back in 1970 – by finding songs and helping people discover new music. (Levine, 2007, p. 80; see Taylor, 2012)

Workers in the advertising industry perform similar roles today. Their constant seeking of the hip and the cool in popular music in order to employ it in commercials has made them in some sense even more important than music supervisors, since advertising drives broadcasting in the US.

These new cultural intermediaries are part of what Pierre Bourdieu (1984) called the new petite bourgeoisie: people with generally high cultural and/or educational capital from relatively privileged backgrounds, but who have opted out of the professions in order to work in the culture industries (see also Featherstone, 2007). I have not interviewed music supervisors to see if they fit this profile, but those in the advertising industry whom I have interviewed generally do (see Taylor, 2012). While Bourdieu's new petite bourgeoisie mediated between high culture and the masses, in today's world the ideology of the hip and the cool has become so dominant that it is coming to displace the role of high art (or what Bourdieu called “legitimate culture”); so what is mediated is no longer high culture as much as it is the hip and the cool (see Taylor, 2009). The hip and the cool is closely linked to youth culture, and I would thus link its importance to the ideology that values youth over age and experience, discussed by Sennett (1998).

The ideology of the hip and the cool, to which the advertising industry is particularly sensitive, has allowed this industry to become extremely influential in the production of culture – so influential that, as I concluded (Taylor, 2012), to make a distinction between “advertising music” and “music” is today essentially meaningless.

Music in a Networked World

Most readers over the age of 30 probably have a memory of how Things Had Really Become Different with the advent of digital technologies, but perhaps especially of the Internet. For me, the year was 1996. I was in the throes of writing my book Global Pop (Taylor, 1997) when a magazine chronicling the life and culture of the Himalayas arrived in the mail. There was an article about a popular song that had taken Pakistan and other parts of South Asia by storm. I was quickly able to hear it thanks to a tinny RealAudio link. That was striking enough. Then I went to my local Indian music store, where I heard the music coming over the shop's speakers as I walked in – cassettes had just arrived. The song – “Billo De Ghar,” by Abrar-ul-Haq – was originally released in 1995. An exceptionally catchy tune, even for listeners who don't understand Punjabi and Urdu, it eventually went on to sell over 16 million copies.

It was, of course, new technologies that made music from around the world so easily available to Western musicians. It was thus no accident that the rise of the category of “world music” (to be discussed in the next section) occurred around the same time as the development of digital technologies and the compact disc. Digitization of music made it extremely simple for musicians not only to hear musics from other places, but also to incorporate recorded sounds of non-Western music into their own. Computer software was developed that made the incorporation of previously recorded music into one's own a simple matter, as easy as cutting and pasting in a word-processing application. A musician could sit at her computer and simply pop in a CD and extract what sounds she wanted, or, with a synthesizer, create “any sound you can imagine” (Théberge, 1997).

Sampling (this cutting and pasting of pre-existing music) has become so ubiquitous in the production of virtually all popular musics in the 1990s that libraries of sampled recordings began to emerge that would allow musicians to access vast collections of music to plug into their own if they wanted to give a sense of local color or some other signifier of the exotic. Whereas popular musicians once grappled with questions of genre or style, or with this sound or that, today's musicians increasingly think in extremely specific terms-digitized, atomized, cut-and-paste terms. For example, one electronic popular musician said that he stockpiles recordings to use as potential samples, “and when I'm working on a tune if I need a male Arabic vocal to fit a section I'll see if I have anything which would be suitable” (Marks, n.d.).2

But sampling is only one aspect of the massive and drastic changes that digitization has wrought into the production of music. Live musicians are increasingly unemployed, as digitized recordings or synthesizers replace them. Nowhere is this clearer than in the realm of the production of commercial music, which I have been studying extensively for over a decade. It is clear that, before the rise of digital technologies in the 1980s, musicians' roles in the commercial music realm were fairly confined, and therefore stable: one was a film music composer, a television music composer, a commercial composer (in a descending order of prestige that exists to this day), or an instrumentalist or singer, who could traverse these boundaries a little more freely. Most of these musicians would have had some classical training, or at least could read and write music and play an acoustic instrument. But the introduction of digital music technologies in the 1980s changed all that, for it was young musicians in popular music who were quickest to learn these new technologies and who were able to gain a foothold in the production of popular musics. Steve Karmen, one of the most successful commercial music composers in the 1970s and 1980s, writes of how a client inquired about the synthesizer he used, then told him that his 12-year-old son used the same machine. “When a twelve-year-old kid can produce the same sounds as a twenty-five year pro,” Karmen writes, “it's a sign” (2005, p. 178). Karmen left the business soon afterwards. Those who remain in the music industry have become much more flexible, in contrast to their immediate pre-digital forbears: they might play in a band, produce albums, engineer albums, make music for commercials, and more.

Many of the people I interviewed (for Taylor, 2012) said that what they missed most about the old days of advertising were the live recording sessions with musicians, most of whom are gone now, as so much can be accomplished by a single musician with digital equipment; and the same is true of the production of popular musics more generally. The sociability and synergy that composers, arrangers, and other musicians once encountered in recording sessions is absent. Nick Di Minno, someone long in the industry, recounted to me with some poignancy his attendance at a musician's funeral and seeing other musicians with whom he once had daily contact in the studio, but whom hadn't seen for years (Di Minno, 2009). Many musicians I spoke to said much the same thing, usually with palpable regret and nostalgia.

Musicians whom I interviewed also noted that a kind of sameness has crept into the sound. Some, like Tom McFaul, an important advertising composer, attribute this in part to the decline of live recording sessions – a decline that made the kind of synergy among live musicians impossible.

Using samples and synths also brought about a kind of sameness to the sound of ad music as it has done to pop music. With live dates, the exciting thing was that the personalities of the great players available always made the work distinctive. If our work was not about art, it was at least about craft and musicianship. (McFaul, 2009)

Yet another repercussion concerned, as always, money. Using synthesizers could be cheaper than live musicians. Spencer Michlin, a leading advertising composer in the 1980s, explains it very clearly:

Technology had made it possible for individuals to compete by recording music on synthesizers in their homes. This gave these writers a built-in economic advantage. Let's say that a jingle needed a rhythm section and horns (piano, bass, drums, percussion, two guitars, three trumpets, and two trombones). Add in the union-mandated double scale for leader, plus a contractor and arranger at double scale and a copyist at scale, and that's 18 units on the AFM [American Federation of Musicians] contract [. . .] Unless the composer was a complete pig [. . .] he or she could leverage that advantage by charging the equivalent of, say, nine units and cut the musicians' budget in half money while keeping more of it. (Michlin, 2009)

Also, Michlin said that younger musicians probably weren't union members (ibid.).

The digital music technologies, and the Internet too, as many people told me, made it possible for people outside of the major metropolitan centers to compete, and also made it possible for music production companies in New York and elsewhere to hire musicians at a distance. Outsourcing, what some have described as an important aspect of the new capitalism, is affecting the culture industries as well.

Music in a Globalized World: The Rise of “World Music”

Let me now address the question of globalization in the new capitalism, paying particular attention to the rise of what has come to be known as “world music.” While many of the musics included in the “world music” category have been around for as long as people have made music, the emergence of this label in the late 1980s registered the increasing globalization and interconnectedness of cultures and economies around the world. Since the seventeenth century, the world had been interconnected (Wallerstein, 1974) through colonialism, trade, and other means, and, due to the widespread domination of much of the world by the West, many kinds of music from the West traveled around the world far more frequently than non-Western musics traveled to Western metropolises. But this began to change in the 1980s, as more and more countries around the world developed recording industries (Wallis & Malm, 1984), and as digital technologies made the dissemination of music much faster and easier. Record stores in Europe and the US were increasingly receiving shipments of recordings of music from beyond their borders; but it wasn't the familiar traditional music that retailers had become accustomed to. It was music that sounded like Euro-American popular music but was different: different languages, different sounds.

Shelving this music – from Africa, India, South America, and elsewhere – in the old section labeled “International,” which was populated mainly by recordings of German polkas and ethnographic field recordings of African drumming or Javanese gamelan, made no sense to these retailers. So, in the summer of 1988, a group of English retailers and journalists gathered to debate a new term for labeling this music, and they settled on “world music” (see Denselow, 2004; Taylor, 1997). For a time, the more rock- and pop-oriented music was referred to as “world beat,” but this description proved to be less durable than the more general “world music,” which persists to this day.

Just as ideologies of the new capitalism infiltrated the world of cultural production, with the new importance of “creativity,” the hip and the cool, ageism, and more, new ideas about consumption also emerged. In a world suffused with goods, as Jean Baudrillard writes, ideologies of authenticity become more prevalent (Baudrillard, 1988, p. 170). In the early days of world music there was a good deal of discussion, in the critical press and among fans, about what was considered to be “authentic,” even though all or much of the music placed in this category was recognizably popular music of some form, which non-Western musicians had been hearing for decades through imports of recordings, cassette copies of them, and radio broadcasts. Nonetheless, early on, the critical response to world music was to celebrate whatever was thought to be authentic and to condemn music thought to be overly influenced by Euro-American popular music.

In Taylor (1997) I identified three forms of authenticity that were common in the marketing and representation of world music of that era: authenticities of positionality, of emotionality, and of primality. These were interrelated ideologies that colored how Western listeners tended to hear music. The first was an ideology that expected non-Western musicians to be truly from the Brazilian favela or Indian slum or Australian outback or African bush; musicians with more than a modicum of educational and financial capital were seen to be not authentic enough in various ways, to the exasperation of many a musician. As the Beninoise singer Angélique Kidjo said:

There is a kind of cultural racism going on where people think that African musicians have to make a certain kind of music. No one asks Paul Simon, ‘Why did you use black African musicians? Why don't you use Americans? Why don't you make your music?” What is the music that Paul Simon is supposed to do?’” (Burr, 1994, §H, p. 28)

Elsewhere she said:

I won't do my music different to please some people who want to see something very traditional. The music I write is me. It's how I feel. If you want to see traditional music and exoticism, take a plane to Africa. They play that music on the streets. I'm not going to play traditional drums and dress like bush people. I'm not going to show my ass for any fucking white man. If they want to see it, they can go outside. I'm not here for that. I don't ask Americans to play country music. (Wentz, 1993, p. 43)3

The second type, what I called “authenticity of emotionality,” refers to the kind of unfettered emotions that non-Western musicians are supposed to possess and to articulate in their music, as opposed to the overproduced and commercial orientation of music that is characteristic of Western popular music.

Lastly, authenticity of primality refers to expectations that non-Western musicians are closer to nature, to the earth, than Westerners – an ideology that goes back at least to the “discovery” of the New World. This belief was registered in the names of many an independent record label that sprung up in the 1980s and 1990s to offer world music such as EarthBeat!, Earthworks, GlobeStyle, Original Music, Real World, Redwood Cultural Work, Roots Records, Soundings of the Planet, and, in German, Erdenklang (“Earthsound”).

These authenticities – or, more appropriately, these ideologies – are not confined to the realm of world music but circulate in Western culture more generally, though they found a particular valence in the realm of world music. Take the authenticity of positionality, for example: many readers will recognize how this particular ideology has surfaced with respect to the marketing and representation of hip hop musicians, whose street credibility is frequently part of their image; or concerns at the height of Bruce Springsteen's fame about whether or not he was truly of the working class.

Interestingly, however, these concerns about authenticity didn't last long, and critics soon began celebrating the clever stylistic hybrid, often characterizing a non-Western/pop hybrid as “authentic” in much the same terms that had once been reserved for describing music thought to be truly authentic (Taylor, 2007). This is perhaps because ethnographic recordings proved to be not so popular with listeners, and also because aesthetic distinctions came to be more important: was the music good or not?

A striking example of the shift in the authenticity discourse of primality combining with ideologies of the hybrid remains Welenga, a 1997 collaborative album between Wes Madiko (a Cameroonian who goes by his first name only) and Michel Sanchez, one of the two musicians behind the highly successful “band” Deep Forest. This album is accompanied by extravagant prose that contains some of the longstanding underlying ideologies about non-Western musicians:

Having written his first traditional album (which only appeared in the USA), Wes was wary of facile and over-artificial associations, a form of white-gloved slavery that is at the heart of too many fashionable cross-cultural projects. He was, however, reassured by the sincere passion of Michel Sanchez, who for three years gave Wes his time and his know-how. The combination of the two spirits, the irrational Wes and the virtuoso Michel, was a fusion of fire and water, the meeting of a wild but fertile root and the gifted loving caretaker of a musical garden where Wes could flourish. (Liner notes to Welenga, 1997)4

The use of language that sounds politically correct, juxtaposed with old and familiar colonialist tropes – of African people represented as “irrational” and “wild,” as well as of the largesse of the European musician – is striking here (for more on this, see Taylor, 2007, pp. 141–143).

Popularization of world music was aided immeasurably by the popular and critical success of Paul Simon's Graceland from 1986, which won a Grammy award for Best Album in 1987. Simon's work with Ladysmith Black Mambazo (a male chorus from the township of Soweto that had already garnered significant international attention), as well as with other African musicians, helped introduce non-Western popular musics to mainstream audiences, and it also helped Ladysmith Black Mambazo achieve the international audience it had been seeking.

Simon's rhetoric and practices around this recording were, and remain, emblematic of the kinds of maneuvers that famous Euro-American musicians have employed to justify their work with other musicians. Their discourses frequently employ a mixture of tropes of discovery and connoisseurship, statements of affection for the music, an aesthetics in the spirit of “art for art's sake,” assumptions that non-Western music needed to be refined in some way, the importance of finding a local guide, and, sometimes, discourses of artistic rejuvenation.

Simon's many statements on the genesis of the album and its reception touch on most of these themes, forming almost a Rosetta Stone of the ideologies surrounding the perception of world music. In a documentary entitled Paul Simon: Born at the Right Time, Simon relates how he became interested in this music when he was at a low point, both in his public and in his private life.

When you have a career crisis and when you have a personal crisis, you can get thrown into a tailspin. And that's what happened then. And I began to come out of it when I began to get interested in South African music. I had this tape called Gumboots: Accordion Jive Hits which I was playing in my car for months.5 It's just an instrumental album. Then I noticed that I was singing whenever the album was playing. I was singing over it. (Paul Simon: Born at the Right Time, 1992)

Simon says that to be at a low ebb in his career was liberating, for it allowed him to do whatever he wanted. So he decided to go to South Africa to look for the music he had been listening to. He was forthright about his desire to jump-start his career: “People said ‘Oh, he went to revitalize his career by using African rhythms.’ I mean, nobody thought that was a good idea” (ibid.). After about a week into his first trip to South Africa in 1985, Simon met Ray Phiri, leader of the band Stimela, and says: “He was the key. Because he could lead me where I wanted to go. Graceland never could have been done without Ray” (ibid.). Referring to South African musics, Simon also says: “Culture flows like water. It isn't something that can just be cut off” (quoted by Herbstein, 1987, p. 35). Later, when speaking of the album that followed Graceland – his The Rhythm of the Saints – Simon says: “The act of discovery becomes what the work is about” (Paul Simon: Born at the Right Time, 1992).6

While Simon's discourses about Graceland and The Rhythm of the Saints provide particularly rich sites for unearthing underlying ideologies surrounding the appropriation of world music by Euro-American musicians, many musicians employed these tropes in various ways. Album art would include photos of intrepid musicians “discovering” world music (a verbal trope employed by Simon), or “primitive” musicians juxtaposed with pieces of Western technology such as headphones or microphones; or they would depict these musicians in recording studios. Some construed local musicians as “guides,” as did Paul Simon vis-à-vis Ray Phiri. And non-Western musics were always naturalized, as in Simon's comment about culture flowing like water.

Once world music became a recognized part of the market (however small – it doesn't rate separate sales figures in the annual tally by the Recording Industry Association of America, which keeps track of such things), a process began – as it must under capitalism – of defining, delimiting, and demarcating it. In today's consumer culture there are tremendous pressures for standardization. Everyone is familiar with this when the product is an automobile or a fast food burger; but in the realm of cultural production the question becomes more complicated. Even though new genres of music always seem to proliferate – demonstrating a seeming fecundity of production – the music industry is constantly seeking ways to clarify and simplify: it is always necessary to know where to shelve the recording, when to program what music on the radio and on what kind of station, where to organize the music online, and the like. Genericization occurred not as the result of racism or xenophobia, and not even of ignorance, but because the Western music industry sought to turn this vast collection of the world's musics – from Indian ragas through Persian songs to the most recent popular music from Africa or India – into a manageable “genre,” within which certain “styles” could be codified.

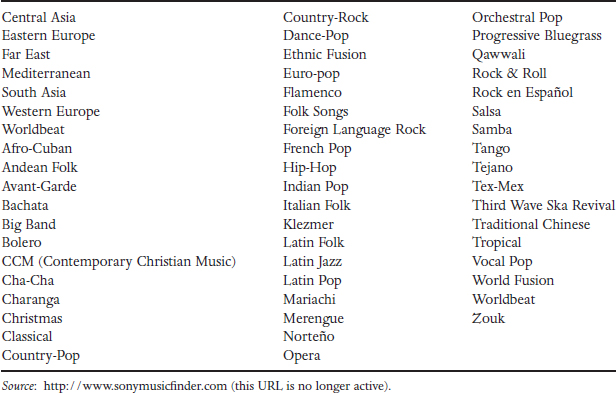

Another reason for this genericization was the rise of the music supervisor in the 1980s, discussed above: this was part of the growing use of preexisting music in film and broadcasting. Various tools sprung up to help music supervisors and others in the music industry to find music suitable for such usages. One such tool was Sonymusicfinder, which allowed users to search for music by genre, style, and mood (mood being an all-important feature of music in film and broadcasting, as it underlies the story and images; see Taylor, 2012). World music was listed as a “genre”; the list of “styles” that appears in the pulldown menu contained, first, geographical regions (excluding North America), and then “styles” (see Table 6.1).

Many of these more obscure (or unusual) “styles” had few recordings associated with them. For example, searching for “Avant-Garde” without inputting a mood resulted in only Tan Dun's homage to Peking opera: Bitter Love (1998). Searching in a similar way for the “style” called “classical” resulted only in A Nordic Festival (1991), with Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra as it performed compositions by well-known and not so well-known Scandinavian composers. “Country Pop” resulted in a handful of songs sung by singers such as Willie Nelson, George Jones, and others – hardly world music; “Country Rock” yielded a single album, Poco (1970), by Poco (this discussion is from Taylor, 2007, pp. 191–194). Interestingly, however, these sorts of tools were underused; professionals in music and broadcasting prefer to hire music supervisors than to search for music themselves, and music supervisors usually use iTunes and YouTube to find music.

Table 6.1 List of world music styles from Sonymusicfinder.com

With the rise and subsequent genericization of world music, people with new skill sets have sprung up. The demands, in the 1980s and early 1990s, for “authenticity” in world music have given way to a market that rewards the individual singer who can mimic any sound – that is simply cheaper and more efficient than finding an actual practitioner of a particular musical tradition. I have talked to singers who specialize in singing vocal parts in films, in television shows, and in commercials, who speak of the importance of knowing how to sound like whatever the producer wants. One told me that, when she is emulating an African American singer, she is frequently directed to sound “a little more white”; when she imitates a singer, she might be told to sound “three years older” (Steingold, 2009). When representing a non-Western style, she could be told to sound “less ethnic.” Another singer told me he has a vast personal library of recordings that he references when he is asked to sing in an unfamiliar style (Crenshaw, 2009).

One of the things that the rise of world music made clear is that old assumptions about the nature of the middle class and its tastes began to shift. World music is associated with a certain portion of the middle class: Bourdieu's (1984) “dominated dominant” group – in other words, people with high amounts of educational and cultural capital but not with financial capital. Demographic data compiled by record labels revealed that world music customers were highly educated and probably multilingual (see Taylor, 2007). This is perhaps not surprising. Surprising is the realization, in the last couple of decades, that dominant groups' tastes in music have shifted, in part because of the looming presence of baby boomers in the overall population – a demographic that has tended to remain faithful to the music of its youth rather than ageing away from it (thanks in part to advertisers' relentless targeting of this demographic group; see Peterson, 1992, 1997; Peterson & Kern, 1996; Peterson & Simkus, 1992; Taylor, 2009).

Unlike some (e.g., Sklair, 2001), I have been reluctant to argue that there is a new social class in the new capitalism. I remain enough of a Marxist to think that capitalism produces its forms of dominant and subordinate groups, in a structure that has proved to be quite durable – it is rather the nature of these groups that has changed over time, changing also with the new capitalism. And, as we learned from Bourdieu (1984), with changes in the social structure, peoples' tastes change. Particularly in this capitalism, which is more culturalized than in earlier moments of its history, the makers and shapers of culture – in this case, the new petite bourgeoisie – can promote their tastes over the culture, through broadcasting and filmmaking, thus influencing consumption. Indeed the oversized role that the advertising industry plays in cultural production today, and its long infatuation with youth, the hip, and the cool (see Frank, 1997), have meant that long-standing cultural hierarchies are shifting. Cultural capital in Bourdieu's sense accrues less and less to those with knowledge of the fine arts and increasingly to those with knowledge of the hip and the cool (Taylor, 2009).

Conclusions

Writing about the present time and the recent past, as I have done in most of my work, makes it difficult to resist thinking about the future. It is not easy to be optimistic. The plethora of musics available means that finding a way through them will continue to be important, both for consumers (including music supervisors and advertising agency workers) and, of course, for musicians. But the predictions implicit in the early songs of praise about the Internet and its implications for musicians have, by and large, not come to pass. It is true that musicians can more easily distribute their music than they could in the past – but distribute it to whom? Identifying and exploiting markets is, increasingly, the main enterprise of the music business, or what remains of it. In any event, it is still out of the reach of virtually all the musicians who simply want to make a living by making music.

And, as great as my debt to Marxian studies of capitalism is, and as helpful as periodizations of captialism are in attempting to come to grips with its multifarious and ever-adaptable nature, it is difficult today to imagine writing of its final phase, its obituary. Anthony Giddens once wrote of modernity as a juggernaut (Giddens, 1990), but it is capitalism that is in the driver's seat. All we can do is hang on and hope to find some good tunes on the radio along the way.

NOTES

1 For an overview, see Harvey (1985); for trenchant critiques, see Ferguson (2002) and Klein (2008).

2 For more on this ideology of sampling, see Taylor (2001).

3 At the same time, as Louise Meintjes (2003) has shown, some non-Western musicians such as those South Africans she studied increasingly make music aimed at an international audience.

4 I would like to thank Harriet Whitehead for introducing me to this album.

5 Ray Phiri, one of the main South African musicians on the album, said that Simon's copy was a bootleg version from London and that Simon had no idea about what the music was or where it was from, and he solicited the aid of his record company, Warner Bros., to track down the source (Mgxashe, 1987, pp. 31).

6 Despite the recording's popularity and critical acclaim, the album was nonetheless controversial, for Simon violated a United Nations boycott against South Africa and, in addition, many listeners both in and out of South Africa heard the album as yet another instance of White appropriation of Black music, or of European/American exploitation of Africa. Simon's statements on this controversy continue the rhetoric he had employed throughout the project: that he was helping the musicians get their music known, that the South African music is nothing but good tunes, and that musicians themselves do not employ criticisms based on politics (see Moerer, 1991).

REFERENCES

Backer, B. (2004, May 4). Telephone interview with the author.

Baudrillard, J. (1988). Simulacra and simulation. In Jean Baudrillard: Selected writings (M. Poster, Ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Boltanski, L., and È. Chiapello. (2005). The new spirit of capitalism (Gregory Elliott, Trans.). New York, NY: Verso.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste (R. Nice, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1998). Acts of resistance: Against the tyranny of the market (R. Nice, Trans.). New York, NY: Free Press.

Burr, T. (1994, July 10). From Africa, three female rebels with a cause. New York Times, §H, p. 26.

Castells, M. (1996). The information age: Economy, society and culture. Vol. 1: The rise of network society. Oxford, UK: Wiley – Blackwell.

Coupland, D. (2010, September 12). A dictionary of the near future. New York Times, §A, p. 29.

Crenshaw, R. (2009, October 19). Telephone interview with the author.

Denselow, R. (2004, June 29). We created world music. Guardian. Retrieved April 2, 2012, from http://arts.guardian.co.uk/features/story/0,11710,1249391,00.html

DiCola, P. (2006, December 13). False premises, false promises: a quantitative history of ownership consolidation in the radio industry. Retrieved March 14, 2010, from http://www.futureofmusic.org/article/research/false-premises-false promises

Di Minno, N. (2009, September 9). Telephone interview with the author.

Ehrenreich, B. (1989). Fear of falling: The inner life of the middle class. New York, NY: Pantheon.

Featherstone, M. (2007). Consumer culture and postmodernism (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ferguson, J. (2002). Global disconnect: Abjection and the aftermath of modernism. In J. X. Inda & R. Rosaldo (Eds.), The anthropology of globalization: A reader (pp. 136–53). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Flew, T. (2009). The cultural economy moment? Journal of cultural science, 2. Retrieved April 2, 2012, from http://cultural-science.org/journal/index.php/culturalscience/article/view/23/79

Foucault, M. (2008). The birth of biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979 (M. Sennelart, Ed., & G. Burchell, Trans.). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Frank, T. (1997). The conquest of cool: Business culture, counterculture, and the rise of hip consumerism. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Harvey, D. (1985). A brief history of neoliberalism. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of postmodernity: An enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Herbstein, D. (1987, July/August). The hazards of cultural deprivation. Africa Report, 32, 33–35.

Jameson, F. (1984, July/August). Postmodernism, or, the cultural logic of late capitalism. New Left Review, 146, 53–92.

Karmen, S. (2005). Who killed the jingle? How a unique American art form disappeared. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard.

Keil, C., & S. Feld. (1994). Music grooves: Essays and dialogues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Klein, N. (2008). The shock doctrine: The rise of disaster capitalism. New York, NY: Picador.

Lash, S., & Urry, J. (1994). Economies of signs and space. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1969). The elementary structures of kinship (J. H. Bell, J. Richard von Sturmer, & R. Needham, Trans.). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Levine, M. (2007, February 1). Q&A: Jack Rudy. Electronic Musician, p. 80.

Mandel, E. (1978). Late capitalism (J. de Bres, Trans.). New York, NY: Verso.

Marks, Toby (n.d.). Interview with Banco de Gaia. Retrieved March 14, 2010, from http://www.chaoscontrol.com/archive2/banco/bancosamples.html. This URL is no longer active

Meintjes, L. (2003). Sound of Africa! Making music Zulu in a South African studio. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mgxashe, M. (1987, July/August). A conversation with Ray Phiri. Africa Report, 32, 31–2.

Michlin, S. (2009, July 28). Personal communication.

Moerer, K. (1991, January). Paul Simon's rhythm nation. Request, pp. 26–32.

Newman, K. M. (2004). Radio active: Advertising and consumer activism, 1935–1947. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

Nixon, S. (2003). Advertising cultures: Gender, commerce, creativity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Paul Simon: Born at the right time. (1992). Burbank, CA: Warner Reprise Video [Motion picture].

Peterson, R. A. (1992, August). Understanding audience segmentation: From elite and mass to omnivore and univore. Poetics, 21, 243–258.

Peterson, R. A. (1997, November). The rise and fall of highbrow snobbery as a status marker. Poetics, 25, 75–92.

Peterson, R. A., & Kern, R. M. (1996, October). Changing highbrow taste: From snob to omnivore. American Sociological Review, 61, 900–907.

Peterson, R. A., & Simkus, A. (1992). How musical tastes mark occupational status groups. In M. Lamont & M. Fournier (Eds.), Cultivating differences: Symbolic boundaries and the making of inequality (pp. 152–86). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Qureshi, R. B. (Ed.). (2002). Music and Marx: Ideas, practice, politics. New York, NY: Routledge.

Scott, A. J. (2008). Social economy of the metropolis: Cognitive–cultural capitalism and the global resurgence of cities. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Seeger, A. (2004). Why Suyá sing: A musical anthropology of an Amazonian people [1987]. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Sennett, R. (1998). The corrosion of character: The personal consequences of work in the new capitalism. New York, NY: Norton.

Sennett, R. (2006). The culture of the new capitalism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Simon, P. (1986). Graceland. Warner Bros. W2-25447 [Compact disc].

Simon, P. (1990). The rhythm of the saints. Warner Bros. 9 26098-2 [Compact disc].

Sklair, L. (2001). The transnational capitalist class. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Smythe, D. W. (1977). Communications: Blindspot of Western Marxism. Canadian Journal of Political and Social Theory, 1, 1–27.

Steingold, M. (2009, October 15). Interview with the author, Los Angeles, CA.

Taylor, T. D. (1997). Global pop: World music, world markets. New York, NY: Routledge.

Taylor, T. D. (2001). Strange sounds: Music, technology and culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Taylor, T. D. (2002). Music and musical practices in postmodernity. In J. Lochhead & J. Auner (Eds.), Postmodern music/postmodern thought (pp. 93–118). New York, NY: Routledge.

Taylor, T. D. (2007). Beyond exoticism: Western music and the world. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Taylor, T. D. (2009, December). Advertising and the conquest of culture. Social Semiotics, 4, 405–425.

Taylor, T. D. (2012). The sounds of capitalism: Advertising, music, and the conquest of culture. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Taylor, T. D. (in press). Late capitalism, globalisation, and the commodification of taste. In Philip Bohlman (Ed.), The Cambridge history of world music. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Théberge, P. (1997). Any sound you can imagine: Making music/consuming technology. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Wallerstein, I. (1974). The modern world-system: Capitalist agriculture and the origins of the European world-economy in the sixteenth century. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Wallis, R., & Malm, K. (1984). Big sounds from small peoples: The music industry in small countries. London, UK: Constable.

Wentz, B. (1993). No kid stuff. Beat, 42–45.

Wes. (1997). Welenga. Sony Music 48146-2 [Compact disc].

Wes. (1997). Liner notes to Welenga. Sony Music 48146-2 [Compact disc].

FURTHER READING

Byrne, D. (1999, October 3). I hate world music. New York Times, §2, p. 1.

Lash, S., & Urry, J. (1987). The end of organized capitalism. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Martin, D.-C. (1992). Music beyond apartheid? In R. Garofalo (Ed), Rockin' the boat: Mass music and mass movements (pp. 195–207). Boston, MA: South End Press.