1

Media Research Paradigms

Conceptual Distinctions, Continuing Divisions

Slavko Splichal and Peter Dahlgren

ABSTRACT

Media and communication research is often believed to represent one of the youngest research areas in the social sciences, but the first essays discussing the nature and social functions of newspapers were written long before the birth of the modern social sciences. The great variety in forms of communication is also reflected in the diversity of research approaches and methods. This chapter deals with these differences and diversities in a broader perspective to demonstrate that it is not methodology itself that determines the differences in approaches but, rather, differences in methodologies that reflect more substantial (theoretical, epistemological, ideological) differences. The chapter begins with a conceptual discussion about academic fields and paradigms. It then discusses the somewhat ambiguous intellectual history of the field and its loose organizing logics. It sketches the contours of the dominant paradigm and its two main challengers over the past decades – the interpretivist and the critical paradigms – and considers some key challenges and controversies that shaped the field's earlier years. Finally, it explores a possible new matrix for structuring research in the field.

Communication as a generic human activity is characterized by an ever greater diversity of its forms, methods, and strategies from simple vernacular languages to highly formalized scientific languages. Significant differences exist between forms of communication – for example, speaking, writing, printing, electronic and digital communication, and many hybrid forms from interpersonal to mass communication – despite the fact that (technological) convergence may diminish these differences in the (near) future by providing more “unified” communication platforms and systems. In this chapter, we address the terrain of media and communication research from the horizon of prevailing paradigms. This academic field of research has been evolving since its inception and continues to do so today, with its main paradigms undergoing transformations internally and in relation to each other. We begin with a conceptual discussion about academic fields as producers of knowledge; in particular we address the notion of paradigms. From there we approach the somewhat ambiguous intellectual history of the field, and then turn to the loose organizing logics that structure it. Thereafter we sketch the contours of the dominant paradigm and its two main challengers over the past decades, the interpretivist and the critical paradigms. With these elements in place, we look at some key conflicts that shaped the field's earlier years, and in the last section we explore a possible new matrix for structuring research in the field, building on the model for the social sciences proposed by Michael Burawoy.

Approaches, Methodologies, Paradigms

The great variety in the circumstances of mediated communication situations is reflected in the diversity of research methods deployed, from ethnographic studies, participatory observation, historical and genealogical analysis to experiments, surveys, textual analysis, and visual methods. Media and communication research ranges from idiographic approaches focusing on subjectivity, uniqueness, and comprehensive understanding of each individual or communication event, to nomothetic approaches emphasizing the importance of objectivity, general properties, and rules in a phenomenon and thus the need of generalization and necessity of probabilistic explanations. Differences between the two general approaches are not only related to theory but also to empirical research: idiographic approaches are primarily experiential (i.e., based on experience) and thus concrete, whereas nomothetic approaches are empirical in the sense of seeking for evidence to prove theoretical postulates but often abstract (i.e., abstracting from experiential situations; e.g., statistical data on abstract phenomena such as gross national product (GNP)).

Nomothetic approaches are often associated with the idea of quantification whereas idiographic approaches give preference to qualitative methods. The preference for one or other type of method often became a matter of (even ideological) controversy about the scientific merit of research, with advocates of quantitative methods arguing that only by using such methods can the social sciences become truly scientific and their opponents who favor qualitative methods proving that quantitative methods tend to obscure the substance of the social phenomena under study which is not directly measurable.

Nevertheless, the differences in methods between the two approaches do not imply disciplinary divisions, as there is no common method(s) that could ultimately ground or substantiate a scientific discipline or field of communication. Still, it is important to critically address the methodological differences and diversities in a broader perspective to make clear that the emphasis on methodology as the site of divisions within a discipline or field of study – that is, between two approaches or any subfields within/between them – is misleading. This is because such a view suggests that it is primarily methods that divide a field or discipline, rather than “historical, economic, political, organizational, professional, and personal factors which impinge on the research process in so many ways” (Halloran, 1981, p. 1). As Merton (1945, p. 463) argued, “problems of methodology transcend those found in any one discipline, dealing either with those common to groups of disciplines or, in more generalized form, with those common to all scientific inquiry. Methodology is not peculiarly bound up with sociological problems.”

Thus, the essence and specific differences in research are not determined by method(ology) itself (e.g., differences between “qualitative” and “quantitative” methods) but, rather, differences in the methods used may at best reflect more substantial theoretical, epistemological (and perhaps ideological) differences and controversies underlying the research process. It is not the method or a set of methods that define a discipline or disciplinary “paradigm.” A paradigm is not method-driven; rather, it implies some underlying substantial theoretical and epistemological assumptions which may promote certain methods as more appropriate in pursuing research aims, and ignore or rebuff others as inappropriate. Specifically, the idea that predominantly quantitative nomothetic approaches and mainly qualitative idiographic approaches are mutually exclusive or, at least, differ in terms of scientific objectivity (e.g., the former being more objective and the latter more subjective) assumes that the unity of the sciences is grounded in sameness rather than complementarity of methods, and subsequently that the social sciences and humanities require the same kind of (quantitative) methods as the natural sciences in order to be “sciences.”

The belief that (a higher) scientific objectivity (validity and reliability) can be achieved only by the use of quantitative methods which “unfetter” research from all contextual factors does not pertain to the nature of methods and the logic of research procedures. The decontextualization of research from its social settings, which the use of quantitative methods is supposed to achieve, does not make research more objective but rather more objectionable. Separation of qualitative and quantitative methodology means divorcing method from the substance of research. Any preference for either qualitative or quantitative approaches prior to a clear conceptualization of the research problem is arbitrary. The idea of an exclusive disjunction of methods (the exclusive “or”: the use of either quantitative or qualitative methods but not both) reflects more a prejudice against the “other” than the true nature of divergence between paradigms. Quantification gives the impression of impersonality, disinterestedness, and impartiality of research(ers) but it does not really protect it/them from subjectivity – not only when it comes to the choice of research methods and procedures, but also and primarily in the selection of research questions and the ways in which they are addressed or suppressed in both empirical research and theory. This is not simply to say that “quantification is nothing but a political solution to a political problem [b]ut that is surely one of the things that it is” (Porter, 1995, p. x).

The selection of “relevant” theories, frames of reference, research questions, and methods is always related to the interests and values of researchers and constrained by “external” (political, ideological, financial, temporal) factors. In some cases, we may even speak of “paradigmatic blindness” censoring certain approaches and methods, when researchers “work from models acquired through education and through subsequent exposure to the literature often without quite knowing or needing to know what characteristics have given these models the status of community paradigm” (Kuhn, 1962/1970, p. 46). Such “imitative” practice may imply aprioristic preferences for either qualitative or quantitative methods; these aprioristic preferences may even match with specific paradigms. Nevertheless, it is particular concepts, research aims and questions, and (often tacit) assumptions internalized by researchers rather than specific methods that indicate and reflect a particular paradigm (or a particular political and ideological perspective).

For a complex field of study or a metadiscipline that cannot be defined in terms of scientific specialty and a single expert community – which we believe communication and media represent as they are interlaced with social, economic, cultural, and political contexts and thus not a unique area of any single scientific discipline – it is even less plausible that all the differences within the field could be accounted for merely by an (exclusive) set of specific research methods.

Kuhn's concept of paradigm as “the entire constellation of beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by the members of a given community” (Kuhn, 1962/1970, p. 175, emphasis added) is inconsistent with his narrower view that “A scientific community consists . . . of the practitioners of a scientific specialty” (p. 177). Obviously, not all the practitioners share “the entire constellation of beliefs.” Moreover, if we assume that there are not very many beliefs, values, techniques, and so on shared by all practitioners of a scientific specialty on a global scale (which we believe is a realistic assumption), the concept of the paradigm is an empty concept. In contrast to Kuhn, we understand (disciplinary) “paradigm” in a more strict sense; it does not refer to all members of a scientific community/specialty but rather to a consistent system of (particularly epistemological) assumptions about method, object, and definition of the discipline underlying research which is rarely shared by all members of a scientific discipline or field of study. As we argue in this chapter, while paradigms have specific historical trajectories, they are not historically consecutive and mutually exclusive (in the sense that some, but not all are “scientific”), but rather mutually irreconcilable in maintaining differences and simultaneously competing within a given discipline or field of study (i.e., all may be “scientific”).

Ambiguity of “Media and Communication Research”

Although media and communication research is often believed to represent one of the youngest research areas in the social sciences, many social scientists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were already very conscious of the social significance of communication. Questions about the workings of communication arose in Western civilization in the early history of the “science of sciences, the science of society, of human happiness, of the social science,” as first named by William Thompson in 1824 when attention turned from the physical sciences and astronomy to the social and political organization of people (Thompson, 1824, p. 275). They accompanied the development of social systems and played a role in the rise of economic interests and in the success of political institutions, when communication and information became an important asset, a commodity, and a source of power.

Beyond this general historical observation about the origins of communication research, however, remains the ambiguity of the concept itself, since “communication research” may embrace pre-Socratic interests in rhetoric as well as modernism's curiosity about the effects of media and communication in society. Equally ambiguous is the idea of “mass communication research,” which may range from seventeenth-century interests in the workings of newspapers to twenty-first-century inquiries about the Internet. However, if one considers the concept of “communication” or “mass communication” itself, the pertinent time period ranges from the late nineteenth century, when “communication” described the movement of people and words, for example, roads and the telegraph, to the mid-twentieth century, when the word “mass communication” was coined in the United States to refer to the world of media. The notion of “media,” in turn, can refer to a wide historical range of technical apparatus and procedures, from clay tablets to DVDs. With the technical convergences of the digital age, the term becomes particularly slippery: is the Internet a medium? Or many media? Is YouTube a medium? We are faced with – and will no doubt have to live with – many conceptual quandaries.

In addition, there is the concept of “research.” Understood as a systematic inquiry into a subject matter, the notion of research accompanies the rise of Western civilization, in which the curiosity of individuals expanded public knowledge and resulted in an increasingly sophisticated understanding of phenomena that affect people's lives, like speech, writing, or language itself. Research relies on the rise of analytical practices, that is, on the nature of questions and the questioning process that have emerged over the centuries. From this angle we can specify the major intellectual concerns – the important issues – which encouraged questions about the role of communication, for instance, regarding the press, its role in society, including its effects, the uses made of newspapers, and the organizational nature of journalism. This view of media and communication research, as an integral part of a history of Western culture, identifies the field with a larger, more comprehensive and holistic vision of exploring human practices, including communication.

Long before the birth of modern social sciences, in the seventeenth century, the first essays discussing the nature and social functions of newspapers were written by empirically minded professionals who did not reflect on the conceptual issues of communication. From the mid-1800s, however, scholars acknowledged that the invention of printing introduced substantial changes in the way people (inter)acted socially. The press became “the real transmitter in the intellectual exchange between the leading organs of society and the public” (Schäffle, 1875, p. 444), differing from other forms of communication by being “thought-communication between persons who are physically separated” (Knies, 1857/1996, p. 44) and primarily by the fact that it was “a link in the chain of modern commercial machinery” (Bücher, 1893/1901, p. 216). As Tönnies (1922) argued, newspapers were from the very beginning not only intended to supplement privately mediated news in letters, but mostly to spread news intended for a larger public. Early discussions of the social consequences of technological achievements, including the rise of a dispersed audience remind us that many of the themes popularly discussed these days in association with cyberspace have their origins in the emergence of the pre-1900 communication technologies, such as the printing press, telegraph, telephone, and film. When the social sciences achieved general recognition by the end of the nineteenth century, communication became topical if not constitutive for the social sciences and for theories of society in general, particularly in the works of Gabriel Tarde, Ferdinand Tönnies, Robert E. Park, and John Dewey.

In his polemics with Émile Durkheim on the nature of “social facts,” Gabriel Tarde (1903) emphasized that “the elementary social fact is communication or the modification of a state of consciousness by the action of one human being upon another” (Durkheim & Tarde, 2008, p. 761). Tarde defined even his main theoretical concept of “imitation” as “a communication from soul to soul” (Tarde, 1897/2000). He argued pervasively against Durkheim's contention that “A thought which is to be found in the consciousness of each individual and a movement which is repeated by all individuals are not for this reason social facts,” and accused him of ontological illusion and scholastic ontology because of his efforts to separate sociology as a scientific discipline from psychology and philosophy (Durkheim & Tarde, 2008, p. 773). Tarde also rejected Durkheim's holistic idea of finished social wholes and promoted “methodological individualism,” focusing on the components of social interactions and practices.

Communication constitutive of public opinion – “holding and expressing opinions is an interactive process” – is one of the three key forms of the “complex social will,” which represented a conceptual cornerstone of Ferdinand Tönnies's theory of Gemeinschaft (community) and Gesellschaft (society). The difference between community and society lies partly in their mode of communication: traditional handed-down customs and religion are typical of community, whereas public opinion that grows out of reflexive discourse between strangers and is based on reason and (scientific) knowledge is constitutive of society. Tonnies strongly believed in the possibility of the objectivity and unity of science based on interdisciplinarity but also emphasized the need to observe humanitarian and ethical considerations. His approach to public opinion surmounted differences between the “normative” and “empirical” paradigms commonly believed to be incompatible. He combined three levels of inquiry: (1) theoretical (pure sociology constructing or producing theories); (2) applied (application to dynamic historical developments deducing from theories); and (3) empirical (inductive empirical research elucidating and explaining general ideas by specific examples). He advocated the use of both quantitative and qualitative methods in empirical sociology to describe, compare, and uncover regularities in social relations.

Mapping Contemporary Paradigms: Logics of Coherence

Emerging from several disciplines in the social sciences and humanities, the field of media and communication research remains heterogeneous, mirroring both its origins and the profound ongoing developments in the media landscape, as well as its sociocultural significance (McQuail, 2010, offers a map of the terrain). Over the course of several decades, it launched its own academic departments, journals, associations, and conferences. The field developed most rapidly in the United States, which for a long time defined the field and influenced its advancement globally. Today, most universities have departments offering courses and programs about the media. Academic departments go under a variety of names, emphasizing different angles on the field and reflecting national and cultural specificities, but we should be aware that with the advent of the Internet, research on “media” is being carried out in just about all fields of the social sciences as well as many in the humanities; computer sciences are also now a part of the research production within media and communication.

The rapid growth of the field brought about a variety of specializations. Research in the field is divided – though not always clearly – between an academic emphasis with social scientific or humanities horizons, and one that focuses on applied knowledge. This latter emphasis can be geared to the needs of media industries, various organizational actors that make use of the media for their own purposes (corporations, political parties, interest groups, etc.), and occupational practices within the media. The lines between the academic and the practitioner orientations are by no means fixed, and the interplay between the two can be both productive and problematic. Moreover, as neoliberal-inspired management values pervade the universities, academic research is increasingly required to demonstrate its relevance and “impact,” thereby narrowing the space for theoretical and critical efforts.

Though media and communication research is a quite disparate field, we can specify a number of logics that give some practical coherence and can serve as a rough map. The first such logic derives simply from specifying a particular medium. Many researchers focus on, for example, television, radio, the printed press, the Internet, or social media. Others specialize still further and focus, for example, on press history or the television industry. Other studies may encompass more than one medium, for example in a case of journalism research.

A second logic takes its departure from a basic model of the communication process, and thus we can organize research according to its attention to senderr, message, and receiver. In the context of the mass media, this yields, respectively, studies of media institutions, media output, and media audiences and/or users. Research on media institutions examines the conditions, both internal and external, that shape them, for instance questions about regulation, political influence, and organizational routines. The study of media output includes the form, content, and modes of representation, often highlighting specific genres. Research on media audiences can include analyses of the impact of specific output, the uses people make of it, and the interpretations they derive from it. Especially with the Internet and the rise of Web 2.0, the concept of audience becomes problematic, as more and more of the online traffic is user-generated (by so-called “produsers”).

Third, specific topics or themes provide some ongoing coherence to the field. These themes can be broad, such as media effects or (more specifically) media effects on children. Many themes link media studies with particular topics on the wider social research agenda, such as gender and ethnicity, children, health communication, media and social movements, and media and sports. From another angle, some themes derive from particular theoretic and/or methodological developments, for example, agenda setting, media events, or media uses and gratification, and can be applied to a variety of empirical areas.

Finally, and most significantly for the character of the research itself, weaving through the above logics are some basic paradigmatic distinctions. We would reiterate that the notion of paradigm points to tendencies within the field, not to unified factions with clear demarcations. These paradigms basically reflect historically anchored differences in concerns, approaches, epistemological assumptions, and theoretical and methodological orientations; they point to distinct intellectual dispositions. The relationships between them have evolved over time, and the development of the field can be understood to a considerable extent by looking at the emergence, interface, and transitions of these major paradigms.

Tensions: The Dominant Paradigm and Its Challengers

The Dominant Paradigm: An Assemblage

In looking at the field today from a paradigm perspective, we can begin with positing what we – with some admitted conceptual looseness – term the dominant paradigm. We choose this term to acknowledge the obvious heterogeneity of the major directions in research, yet at the same time we want to indicate that there are unifying elements in the prevailing patterns of research in the field. Thus, though the dominant paradigm encompasses a broad (and growing) array of research currents and subcurrents, and it is continually developing new approaches, it is nonetheless united in its basic adherence to traditional social scientific methodologies and approaches to theory. Its intellectual foundations are found chiefly within sociology, psychology, social psychology, and political science, with a dominance of quantitative methods. It constitutes the still hegemonic tradition of empirical research within media and communication. From about 1950 to the early 1970s, the dominant paradigm emerged, solidified, and remained essentially unchallenged. The most prominent orientation was that of media effects – to ascertain the impact of media on people's thought and behavior; the themes of violence and sex, but of course also advertising, were key areas of research (Klapper, 1960, was no doubt the most influential text in this regard). Content analysis of media output constituted the other major trajectory. This was its golden age; since then the heterogeneity of the field has increased.

Gradually, this heterogeneity of the field became problematic; debate and uncertainty began to set in, and over the years there have been a number of calls to better define the core and the boundaries of communication and media research (e.g., “Ferment in the Field,” 1983; “Future of the Field I,” 1993; “Future of the Field II,” 1993). Questions and contentions have been aired about the range of theories and differing methodologies in the field. The vision of a unified science may still have some attraction in some circles, though it is less often asserted these days, and expectation for more field integration seems less intense. One could say that the field of media and communication research remains a somewhat unstable signifier. The large conferences suggest that a relatively harmonious coexistence between different currents prevails within the dominant paradigm (see, for example, the ICA website for current or upcoming conferences). However, in the early 1970s, two paradigmatic challenges began to assert themselves.

The Interpretivist Paradigm

A particular attribute that united the dominant paradigm was its adherence to the strict scientific model, one that builds on the premise that media research (and social research generally) should basically follow the methodological guidelines of natural sciences, using quantitative methods in particular to establish causal relationships. Two sets of critics emerged here, from the interpretivist and the critical paradigms. Both would often use the term “positivism” in criticizing the dominant, though the word was often intended as a general epithet rather than a rigorous concept from the philosophy of science. The interpretivists take the view that human beings are thinking and reflecting subjects driven by meaning; thus research must focus precisely on the meaning of action from the standpoint of the actor. This logic can be found, for example in Weber's notion of Verstehen, that is, understanding as constituting the core goal of social research, clearly demonstrated also in his quest for a systematic and comprehensive examination of the press. The angle taken on communication underlined the processes of meaning or sense making over the transmission of discrete “messages” (Carey, 1989). Research explored the communicative power of symbols, the processes of rituals, the rhetoric of nonverbal gestures, and communicative contexts, among other things.

Interpretivism entered the field from several corners, including the growing orientation of social constructionism (which has since become a sort of doxa in some corners of the field), contributions from the humanities and from the qualitative, interpretive social sciences, and not least the rise of cultural studies. In the 1970s British cultural studies, under the leadership of Stuart Hall (see Hall et al., 1980) had begun to impact media research. The eclectic synthesis of intellectual ingredients in cultural studies – including neo-Marxism, (post)structuralism, feminism, psychoanalysis, semiotics, and ethnography – was applied not only to the media but also to a range of topics having to do with contemporary culture and society. Interpretivist strands emphasize the social construction of meaning (and identities), and the relationship between meaning, culture, and – particularly in the case of cultural studies – power. Methodologically, interpretivist approaches used conceptual toolkits such as hermeneutics, semiotics, psychoanalysis, and narratology and applied them to approaches such as ethnography, interviews, observations, and the analyses of texts and visuals. We can note that cultural studies has grown into a heterogeneous, multidisciplinary field in its own right, with contributions from currents such as postmodernism and postcolonialism, among others. Today studies of the media are only a small part of its vast concerns. As it expanded and became a global academic phenomenon mingling with many other academic traditions, the critical character of its earlier years, where issues of social and semiotic power were thematized, has not always remained evident.

The Critical Paradigm: Three Strands

The critical paradigm likewise has a mixed lineage. The notion of critique derives from G. W. F. Hegel's notion of unnecessary constraints on human freedom, which was adapted by Karl Marx and also mobilized in the various critical traditions since then in emancipatory projects that challenge various forms of domination. Thus, critique fundamentally involves normative reflection on the relations of power. In terms of media and communication research, there have been three major traditions: political economy, the critique of ideology, and theories of the public sphere. However, we should also note that there is an epistemological version of critique, which derives from Immanuel Kant and his Critique of Pure Reason. Here Kant underscores that our knowledge of the world is always mediated in a number of ways; we never have direct access to it. Rather it is shaped by our sense organs, our mental processes, language, specific cultural frames of perception, social location, and so on. This version actually resonated more within the interpretivist paradigm, and can be seen as a link between the two, especially in the work of early cultural studies; its emphasis on identity, ideology, meaning, and so on intertwined critical reflection on power relationships with the development and maintenance of worldviews and particular forms of knowledge and subjectivity.

The Hegelian version of critique was stronger in the various Marxian currents that began challenging the dominant paradigm in the early 1970s, most notably the political economy and critique of ideology traditions. The political economy of the media addresses ownership, commodification, (de)regulation, policy, and the links between economics and the social, political, and cultural dimensions of modern life. The early work of such scholars as Dallas Smythe (1981) and Herbert Schiller (1975) opened up passages that scholars active today further develop (see, for example, Fuchs, 2011; Mosco, 2009). A recurring thematic here is the tension between, on the one hand, the capitalist logic of media development and operations, and on the other, concerns for the public interest and democracy. For the most part, the political economy of the media does not anticipate the elimination of commercial imperatives or market forces, but rather seeks to promote an understanding of where and how regulatory initiatives can establish optimal balances between private interest and the public good, in hopes of redressing some of the worst power inequalities and promoting the democratic potential of media.

The critique of ideology was for a while a very robust current. In the critical lexicon, ideology is not a descriptive term about party platforms or people's systematic worldviews, but refers instead to how representations of the world covertly serve the interests of some groups at the expense of others. In its more forceful versions, the critique of ideology builds on the notion of false consciousness – the systematic misapprehension of one's own (class) interests. Thus the concept is in the business of distinguishing between reality, essence, or truth, and appearance or falsehood. This of course begs the question of what the “truth” is and the term began to wobble under increasingly sophisticated scrutiny. There have been many efforts to “repair” the concept, but gradually, by the end of the 1980s, the concept was moving to the margins, and in the early 1990s it was becoming clear that the epistemologically and methodologically more sophisticated tools of critical discourse analysis (see Fair-clough, 2010) were better suited for elucidating the links between representation, meaning, and power in mediated communication.

Another major – and quite familiar – building block of critical media research frames the issues of media and democracy within the concept of the public sphere, a notion most associated with Jürgen Habermas (1989), but one that figures in the writing of many authors (see Gripsrud, Hallsvard, Molander, & Murdock, 2010, for a collection of key texts). In schematic terms, a public sphere is understood as a constellation of institutional spaces that permit the circulation of information and ideas, as well as the formation of public opinion and communicative links between citizens and the power holders of society. Habermas's (1989) historical analysis examines the structural evolution of public spheres as well as the character of its communicative activities, and can thus be said to straddle the base/superstructure divide. Though the Habermasian model soon raised a number of issues (see Calhoun, 1992), it has provided a strong critical foundation and normative horizon for thinking about the media, participation, and not least journalism, and has inspired countless research initiatives. The concept has some parallels with the liberal notion of the “marketplace of ideas” and similar metaphors, and today it has entered into more common usage where the problems of journalism are often discussed – though often with the risk of losing the critical foundations that derive from its intellectual origins with the Frankfurt School.

Gradually the critical paradigm became more diverse, incorporating not only post- and non-Marxian currents, but also feminism, postcolonialism, and the critical trajectories, for example on race and ethnicity and queer studies. There has been a massive amount of critical artillery aimed at media and communication, taking the dominant paradigm to task on a variety of issues. The epistemological certitude of the Marxian trajectory weakened; for many, Marxism and its emphasis on class became less of a totalizing paradigm and was seen more as one, albeit central, element, together with other currents in media and communication studies that were challenging the dominant paradigm. In the process, critical epistemological reflection became more widespread within the critical paradigm, even if some researchers more wedded to the Marxian tradition challenged what they perceived as unproductive revisionism of the critical tradition. Even today we can find issues over the relative weight to be given to the political economy versus the cultural dimensions of mediated phenomena.

Challenges and Controversies in Media Research

Since Tönnies's time, empirical research has come far in exploring (mass) communication phenomena. Systematic study of communication and media began in the United States in the 1920s under the influence of growing scientific/academic and commercial interests in this generic human ability and need, especially in its most developed and widely commercialized form – mass media. In this context, “mass communication research” found its place in traditional US academic disciplines, such as sociology, psychology, and political science. When by the end of 1950s, “communication research had come gradually to lose its place as a major concern within the conventionally recognized academic disciplines, . . . departments of journalism and other vocationally oriented faculties moved in to fill the vacuum” (Lang & Lang, 1983, p. 130). The institutional transition helped to develop a new field of research (and a “scientific discipline” for some proponents) which was largely characterized – in contrast to earlier interests in the broader societal conditions of mass media and public opinion – by the separation of the study of mass communication from that of public opinion, a strong interest in the effects of mass media on individual behavior and preferences, and the use of quantitative methods in data gathering and analysis. The dominant paradigm had begun to take shape.

Empirical and applied research that made a very dynamic development in the early twentieth century had important and controversial consequences for all the social sciences which have begun to receive a significant position at universities, in governmental offices, and in the corporate world. Professional institutionalization of the social sciences increased interest in the reliability and validity of applied research but also often tended to overemphasize the importance of operational definitions and the empirical reliability of concepts to solve practical problems – while discriminating against the critical role of theory in steering social development. Ever higher costs of experimental and field work led professional research into dependence on the policy world and capital, and separation from civil society. Financial support from corporate foundations required researchers to shed and avoid political radicalism (rather than any political alignment). Critical communication research – an emerging paradigm – was challenged by the idea of a value-free or neutral research, in which the understanding of communication as a cultural transaction and symbolic interaction developed by pragmatism succumbed to a simplistic conception of communication as transmission and/or exchange.

Paradigmatic challenges to media research came into sight most often in the periods of invention and/or dominance of a new quantitative method or approach in empirical communication research, but methodological controversies always reflected broader issues of the nature and function of media (research) in society. We will briefly address three such historical challenges related to methodological innovations:

- the invention of polling and its critiques;

- quantitative versus qualitative content analysis;

- audience research and the dispute on “administrative” versus “critical” research.

Polling: The Separation of Public Opinion from Communication?

The invention of polling in the late 1920s has significantly influenced conceptualizations of public opinion and its role in (mass) societies. Furthermore, it typically divided the academic community into those who admire polling as a tool to make democratic life more efficacious and its critics who argue that it has undermined it fatally. At first glance the main issue at stake in the controversy on “measuring public opinion” may seem to be the quantification of public opinion by using sampling methods, data gathering procedures (e.g., attitude scales), and statistical analysis. However, as it will be made clear, the controversy goes beyond inaccuracies in sampling methods and predictions and primarily refers to the ontological and epistemological status of public opinion versus polling.

The controversies around polling can perhaps be best illustrated with two polar attitudes toward “the science of measuring public opinion,” as Gallup called the innovative research procedure in the collection of interview response data.1 At one extreme, Herbert Blumer blamed polling for the loss of the generic subject as it was not able to “isolate ‘public opinion’ as an abstract or generic concept which could thereby become the focal point for the formation of a system of propositions” (Blumer, 1948, p. 542). Instead of identifying public opinion as an object of study and contributing to its better understanding, according to Blumer, polls actually “constitute” the object of study (“public opinion”) ostensively in the process of sampling, data gathering, and aggregating. The operationalistic understanding of public opinion as an aggregate of equally valid opinions by independent individuals collected from a random sample of population suggests that a public and, thus, society exists as a mere aggregate of disparate individuals in contrast to the actual “organic” operation of public opinion in society. Furthermore, the high predictive validity of election polls (in predicting outcomes of elections) cannot be “extrapolated” to the universal validity of polling because even the most accurate prediction cannot be swapped for explanation, and the accuracy of prediction of election results in election polls cannot be generalized and transferred to any kind of polling.

At the other extreme, Osborne and Rose praised polling precisely for having produced public opinion as a new social phenomenon which “is created by the procedures that are established to ‘discover’ it,” thus making polling similar to the successful natural sciences in creating new phenomena (Osborne & Rose, 1999, p. 382). In other words, according to Osborne and Rose, public opinion was not observable and did not exist in empirical terms prior to the development of interview response data gathering procedures. Public opinion is the result of, and is identical to, sampling, data gathering, and aggregating.

Before the advent of polling, the social sciences made rather unsuccessful attempts at scientific operationalization of the normative concept of public opinion. With polling, however, a satisfactory degree of empirical validity has been achieved, as its prophets and pollsters believed. Gallup praised polls for creating a new momentum to strengthen democracy. He believed, exaggerating James Bryce's enthusiasm, that with polls “the will of the majority of citizens can be ascertained at all times” (Gallup, 1938, p. 14). Following Bryce, Gallup defended an ostensive definition of public opinion as a simple “aggregate of the views men hold regarding matters that affect or interest the community” (Gallup, 1957, p. 23). Polls ought to compensate for the growing limitations to citizens' political participation in parliamentary democracy. Gallup defined polling results as a “mandate from the people” to the government and suggested that polling might help re-establish the town meetings of antique Greece on a national scale. Polling was believed to provide a democratic counterweight to the growing independence of political elites and the separation of representation from popular rule.

The issues of empirical verifiability and the reliability of polling dominated scholarly debates on public opinion to such a degree that, in the 1930s, polling reached the position of the dominant public opinion paradigm, thus shoving aside the traditional normative conceptualizations of public opinion. “The advent of so-called ‘scientific polls’ during the 1930s has gone far toward solving the problem of ascertaining quickly, economically, and accurately the states and trends of public opinion on a large scale,” wrote Childs (1965, p. 45). Polls provided information about individuals' attitudes that is relevant to the political process and predictions of their voting behavior, but also commercially relevant information on the purchasing habits and power of consumers, and on the relationship between advertisements, consumer preferences, and buying decisions, which became a key area in market research.

However, while pollsters hailed polling as part of a solution for the growing democratic deficit, its opponents saw in it a serious threat to democracy – not only did polling not stimulate public discussion, but it even prevented and/or replaced it. Moreover, pollsters were criticized for their erroneous premise that public opinion expressed by a majority in polling should be simply followed by political action in the same way as merchants follow the results of consumers' research. Several critics believed that the main purpose of polling by the government could be manufacturing citizens' opinions and changing those which were not congruent with the course of action, thus marginalizing the power of public opinion.

Controversies on polling are essentially political and theoretical rather than methodological. The specific aims of polls are not their intrinsic functions but are defined by their users and observers. It may well be that polls had been initially designed as a research procedure to “measure public opinion.” Whether or not public opinion is “measurable,” however, is not a methodological but a theoretical issue. Similarly, the embeddedness of polls in the political system resulted in specific political functions (e.g., “illuminating the state of public opinion for the benefit of the representatives of the people,” according to Gallup (1971, p. 227)), which were assigned to polling independently of its methodological drift.

Content Analysis: Issues of Empirical Reliability and Theoretical Validity

As early as in the late nineteenth century, before the first polls were conducted, a sort of “quantitative newspaper analysis” was used to show how the contents of New York newspapers had changed between 1881 and 1893 (Krippendorff, 1980, p. 14). Much earlier, however, the first qualitative content analysis appeared – in censorship. Censors had the task of analyzing written materials in a systematic way to discover forbidden ideas hidden in texts so as to prosecute their authors, as decreed by the ruling secular or ecclesiastic powers. Plato was the founder of the aristocratic idea of censorship that has resounded for more than 2,000 years. In The Republicc, he substantiated the necessity of censorship to prevent narrators and poets from making “an erroneous representation . . . of the nature of gods and heroes” which young people would not be able to understand (Plato 360 BCE/1901).

With the development of the social sciences, content analysis became one of its most important methodological tools. At the beginning of the twentieth century, in a speech to the German Sociological Association, Max Weber called attention to the need for a systematic and comprehensive examination of the press, starting “with scissors and compasses to measure the quantitative change of newspaper contents . . . From these quantitative analyses we will proceed to qualitative ones” (Weber, 1910/1979, pp. 151–152). Unfortunately, Weber's ambitious project did not succeed for a variety of reasons, and World War I ultimately prevented its realization (Hardt, 1979, p. 183).

Content analysis entered its golden period during World War II, with the US government-sponsored War Communications Research Project aiming to analyze enemy propaganda and the “language of communism.” The book on Language of Politics: Studies in Quantitative Semantics (Lasswell et al., 1949), which resulted from the project, inspired many communication scholars to get to grips with quantitative content analysis in the decades to follow. Lasswell insisted on the quantitative approach in order to overcome severe “limitations of qualitative analysis,” such as imprecision and arbitrariness. He argued that the quantitative analysis of political discourse would both advance political science and contribute to policy gains (Lasswell, 1949, pp. 40, 52). Following this reasoning, Bernard Berelson contributed a definition of content analysis as “a research technique for the objective, systematic and quantitative description of the manifest content of communication” (Berelson, 1952, p. 18, emphases added), which dominated the field for quite some time. It not only excluded qualitative approaches to media contents but also limited analysis to “‘manifest content’ [which] exists in the form of black-marks-on-white” (p. 19).

It should be added, though, that Berelson restricted the validity of quantitative content analysis to the sorts of standardized textual material one can find in newspapers, and he warned: “The analysis of manifest content is applicable to materials . . . where understanding is simple and direct . . . Whenever one word or one phrase is as ‘important’ as the rest of the content taken together, quantitative analysis would not apply” (Berelson, 1952, p. 20). Taking this limitation seriously would, according to Berelson, make all interpretive genres with nonstandardized forms and nonconventional contents – where “different members of the intended audience” do not “get the same understanding from them” – entirely inappropriate for “quantitative analysis of black-marks-on-white” (Berelson, 1952, p. 20). The obvious problem is that when texts2 may be understood or “decoded” in a variety of different ways, the principle of empirical reliability of (de)coding (i.e., the need that all coders understand and code each text in the same way) may violate the principle of validity by reducing different readings to the lowest common denominator that still promises reliable quantitative coding. Even if quantitative coding is reliable, it alone does not guarantee valid results. Kracauer (1952–1953) questioned the exclusive use of quantitative content analysis on the ground of its implicit assumption that the frequency of appearance of a characteristic (e.g., a word or a class of words) is taken as the indicator of its importance: the more often it appears, the greater its importance on the whole.

Kracauer emphasized the need to combine the two approaches because “qualitative analysis” and “quantitative analysis” do not refer to radically different methodologies:

Quantitative analysis includes qualitative aspects, for it both originates and culminates in qualitative considerations. On the other hand, qualitative analysis proper often requires quantification in the interest of exhaustive treatment. Far from being strict alternatives the two approaches actually overlap, and have in fact complemented and interpenetrated each other in several investigations. (Kracauer, 1952–1953, p. 637)

Hence, a prejudiced trust in the validity of quantitative content analysis ignores the important role that qualitative (interpretive) examination may play in text analysis and communication research in general.

Administrative Research and Empirical Critique

Theodor Adorno's critical reflection on lessons taught in the Princeton Radio Project (1938–1941)3 still has relevance today for the discussion on the (potential) political implications of empirical communication research. Part of the comprehensive empirical Radio Project was devoted to radio listening habits. Adorno's inside experience with the project suggests that, even compared to the most radical critical theories (in terms of either existing knowledge or prevailing politics), applied research is much more (and more directly) affected by institutional constraints and temptations to yield to conditions defined by funding institutions. This could even lead to the conclusion that any empirical and particularly quantitative research, by necessity, reduces the level of criticism theory can provide, but such a conclusion would be premature, as Adorno admitted.

In his critical appraisal, Adorno indicated that there was little room for critical social research in the framework of the Princeton Project.

Its charter, which came from the Rockefeller Foundation, expressly stipulated that the investigations must be performed within the limits of the commercial radio system prevailing in the United States. It was thereby implied that the system itself, its cultural and sociological consequences and its social and economic presuppositions were not to be analyzed. (Adorno, 1969, p. 343)

Adorno was critical of the implied and perhaps unconscious conformity of professional researchers who tacitly completed research orders and did not dare to question the reasons and consequences of such an investigation, its aims and the methods used to achieve them, the goals and interests of individuals and social groups chosen as research units, and researchers' own actions within it. Referring to the part of the project dealing with music listening, he identified two kinds of questions representing “administrative technique” which are effectively used to manipulate the masses: (1) questions directed toward the reactions of audiences when exposed to certain kinds of programming, for example, “If we confront such and such a sector of the population with such and such a type of music, what reactions may we expect?” or “How many sections of the population have been brought into contact with music and how do they respond to it?” (2) questions directed toward the efficacy of research procedures, for example, “How can these reactions be measured and expressed statistically?” (Adorno, 1945, p. 208).

Such questions resemble questions asked in a laboratory experiment or market analysis where research objects (units) are exposed to different treatments (variables) to find out how effective they are. If experiment or analysis is successful, researchers can recommend the treatment to be applied in order to produce the effect we want to achieve in practice. In terms of “how certain aims can be best realized under the given conditions,” that is, how effective research techniques are used to manipulate the masses, Adorno differentiated between directly “exploitive” research (e.g., aiming at selling certain commodities) and “benevolent administrative research” (e.g., how to bring good music to as large a number of listeners as possible).

An alternative to these manipulative or administrative approaches would be a commitment to design research as social critique, that is, to question the aims “imposed” on research, or at least their successful accomplishment under given conditions:

One should not study the attitudes of listeners, without considering how far these attitudes reflect broader social behavior patterns and, even more, how far they are conditioned by the structure of society as a whole. This leads directly to the problem of social critique of radio music, that of discovering its social position and function. (Adorno, 1945, p. 209)

Although Adorno later explicitly contradicted the interpretation that he rejected empirical social research and underlined that he “consider[ed] these procedures not only important within their own sphere but also as appropriate” (Lang, 1979, p. 93), his attitude toward the use of quantitative methods in empirical research remained uncertain. His suggestion that one possible indicator of administrative research be the statistical measurement of survey response data certainly helped the qualitative–quantitative controversy continue through the decades.

Controversies over administrative and quantitative research in communication vivified in the 1980s after Smythe's and Van Dinh's (re)conceptualization of “administrative ideology” as “the linking of administrative type problems and tools, with interpretation of results that supports, or does not seriously disturb, the status quo” (Smythe & Van Dinh, 1983, p. 118). According to the authors, administrative ideology implies not only “administrative type problems” but also “administrative type tools,” in addition to a specific way of interpreting research findings which “supports, or does not seriously disturb, the status quo.” In contrast to Merton's argument that problems of methodology neither are specific to any single discipline in the social sciences nor imply a particular content of a theory, they seemed to believe that “tools” are specifically tied up with “problems.” Pursuing this idea, Smythe and Van Dinh operationalized “administrative research” by equating it with “quantitative research”:

Under administrative research, the first type of research is for simplicity called “quantitative.” It includes market research . . . it serves the private corporate interests . . . Survey research, conducted with rigorous standards for sampling, variance estimates, and control (but not elimination) of biases involved in questionnaire construction and interview and coding techniques, would also qualify as quantitative administrative research. (Smythe & Van Dinh, 1983, pp. 118–119)

The operationalization tacitly slides from “market research” to “quantitative administrative research” without providing any substantiation for it. While “market research” (with research questions and aims subject to commercial interests and profit) represents a specific materialization of “administrative ideology,” this representation cannot be transferred to the relationship between quantitative methods and administrative ideology, so that “quantitative methods” would indicate “administrative ideology.”

Reducing the “administrative–critical” relationship to “qualitative–quantitative” misplaces the “theoretical–empirical” issue. As the empirical methods are instrumental solutions to the problems of gathering, processing, and interpreting information (data), the choice of specific methods should depend on the subject and the aim of the research. The decisions as to whether it is appropriate to choose qualitative and/or quantitative methods should be based on the respective probabilities of obtaining the evidence being sought, and no method can be a priori excluded as inappropriate, whether quantitative or qualitative. Unfortunately, research practice is often far from such an ideal state.

One of the central issues of empirical research is the theoretic ability of a researcher to differentiate between the quantitatively prevailing and the essential characteristics of objects under study. The essential characteristics of a social phenomenon or fact are never determined by the remains of the old in it, although quantitatively they still dominate, but by the elements of the new, that is, by the direction and aim of the development. In the early phases of the development, the new never appears as quantitatively dominant or as an average, but rather as an “exception” for which only a more thorough and theoretically based research can show that it is actually not a mere coincidence but rather a rule, a result of general development. Yet the task of empirical research may not be reduced to revealing just new (e.g., in contrast to prevailing) phenomenological forms. For social research and policy as well, it is essential to discover the conditions which (may) lead to the affirmation of the new and those which prevent or hinder its further development, and to conceptualize the relationship between them.

Social Media Research: A New Paradigm?

Gabriel Tarde had problems persuading Durkheim that (interpersonal) communication is a fundamental social fact, but in the age of computer-mediated communication and social media, this is beyond any doubt. Social network sites (SNS) – “web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semipublic profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system” (bojd & Ellison, 2007) – became a major object of study in communication research not only because of their popularity but also because of the unprecedented abundance of self-generated data they provide. In traditional research, the data gathering process is clearly separated from the process of communication as the object of study: surveys and text analyses are used to provide data on the already existing (f)acts, whereas the contradictory nature of polls (a tool or an object of study?) was a major source of scholarly controversies.

Internet interactions, links and profiles, and mobile phone uses represent an entirely new mode of communication that combines the timeliness of speaking and the endurance of writing. Moreover, the digital(ized) communicative acts generate “surplus” information on users' online activities that can be tracked down, explored, and used (and eventually even sold) by those not participating in interactions. Without the consent and even knowledge of the participants, rich data sets can be created to study patterns of calling and receiving phone calls, sending and receiving messages, downloading and uploading files, (un)friending and (un)liking on the individual and aggregate levels. This kind of surveillance, coupled with the massive amounts of so-called big data that it generates, raises serious ethical and legal issues. These issues have to do not only with the practices of research; more fundamentally, the collecting, analyzing, selling, and strategic use of such data for commercial or political purposes become problematic for the life of democracy (see Oboler, Welsh, and Cruz, 2012).

What is more, new modes of digital communication also challenge the belief that it is possible to clearly separate methodology from theory. Merton was once critical of inductive empirical research using already existing data sets in which “observations are at hand and the interpretations are subsequently applied to the data,” because in that process an interpretation can always be found to “fit facts” (Merton, 1945, p. 468). Before the advent of computer-mediated communication, the “data at hand” were always generated independently of communication processes under study; they were usually “secondhand” data created in previous research. In digital communication, however, the data sets existing prior to our study consist of “footprints” of personal information participants leave online while communicating, and make them (often unwittingly) available to others. This information is generated automatically by the software enabling communication itself and thus cannot be prevented.

We do not mean to say that the rise of digital modes of communication made communication research methodology-driven. On the contrary, given the ever tight connection between theory and methodology, these developments make critical reflection and development in regard to theory all the more imperative.

For a Reconstituted Matrix of Research

In 1996 what is called the Gulbenkian Commission on the restructuring of the social sciences, chaired by Immanuel Wallerstein, presented its report, Open the Social Sciences. In brief, the report called for a leaving behind of what the authors perceived as outdated disciplinary divisions, vested interests, and dead-end epistemologies. It advocated a unification that would also interface fruitfully with the humanities and the natural sciences. While there was much merit to the report, it also suffered from a utopian universalism and left unanswered such basic questions as for whom and for what the knowledge was meant. In the years since then there have been a number of discussions and debates about it. One such intervention is by Burawoy (2007), on the tenth anniversary of the report. He posits that it is urgent to focus precisely on the questions of for whom research knowledge is intended and for what purposes. In pursuing these questions, he suggests that we distinguish between knowledge production that is aimed at academic audiences – our colleagues – and at others, in the social worlds beyond the university. In regard to the purposes of research, he says we should ask “whether the knowledge concerns the determination of the appropriate means to pursue a given, taken-for-granted end, or whether it involves a discussion of those very ends themselves: that is whether the knowledge is instrumental or whether it is reflexive” (Burawoy, 2007, p. 139).

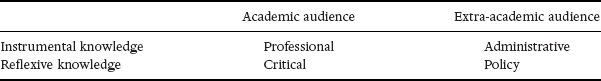

From this line of reasoning emerge four types of knowledge that define a field of research. We have adapted the names of the categories to better fit the circumstances and intellectual history of media research discussed above, and arrived at the four categories presented in Table 1.1.

This matrix, with its four forms of knowledge, would seem to fit the field of media research rather well. We need not concern ourselves with any grand universalizing synthesis of the field; it will no doubt continue with its dominant paradigm and various challengers to it. What the proposed matrix offers is a way to depict and not least to legitimize different forms of knowledge for different purposes, which takes us beyond the constricting confines of a unitary/positivist model of the field.

Table 1.1 Division of disciplinary knowledge

Professional knowledge is for the professional, that is academic, audience. It is the knowledge aimed at ourselves, our colleagues, who have the task of further developing the knowledge that the field embodies. Professional knowledge is instrumental in the sense that it follows established patterns of theorizing and methodological approaches to find out new things. It will continue to be characterized by heterogeneity, coexistence, and disputes over theory and methods. Some specialized corners may become (or remain) incommensurable with others, but we will simply have to live with that and not let the absence of a unifying approach or clear boundaries to the field subvert the overall production of new knowledge.

Administrative knowledge can take many forms in that there are many groups within the extra-academic audiences that have need of research-based knowledge. We carry forward the insights gained from the decades-old discussions about this form of knowledge, for example that it is not a priori quantitative or qualitative in character, and that it can be utilized for benevolent as well as exploitive purposes. Administrative knowledge is geared to the needs defined by the clients; it is instrumental in that its utility is defined by specific goals or ongoing tasks of the clients. Within civil society there are many groups, networks, and organizations, which in various ways have interests that relate to the media. Associations of television viewers, concerned parents, and advocacy groups focused on advertising, political, and corporate interests all have interests in the media that can be served by research.

The groups for whom administrative knowledge is most continuously salient are no doubt the many cadres of personnel and management working within the media, from advertising and journalism, from television production to social media strategists. There is an ongoing demand from media practitioners for up-to-date research on the media and their relations to social, economic, political, and cultural domains. Certainly there can arise some conflicts of interest in regard to public knowledge: advertisers want to reach target audiences, while many such audiences (or their parents) may be more interested in how to avoid or resist media strategies. These conflicts too will simply have to be dealt with as they arise; they do not inherently destabilize this form of knowledge.

Policy knowledge is a reflexive form in that it involves consideration of norms, values, and practices in the media landscape. Policy in the media field is shaped by the intersection of normative considerations with the specific interests and actors involved, such as the state, commercial media institutions, the advertising industry, media production organizations, hardware manufacturers, political parties, citizens' groups, the “common interest” and democracy itself. Research on policy can focus on specific services, how they are to be financed and regulated, the perceived needs of various groups, and involve a normative balancing of conflicting interests. Integral to the policy process are various forms of public hearings where not just stakeholders but the general public are often entitled – at least formally – to be witnesses and participants. Yet, we must acknowledge that research into policy (see Just & Puppis, 2012, for a recent treatment) can at times take on an instrumental character, and this shift in character may well have to do with the power relations involved. Thus, powerful groups may pursue their strategic interests via policy knowledge, eroding its reflexive character and pushing it toward administrative knowledge, with its administrative (and not always benevolent) character. The struggle becomes one of thereby trying to maintain the reflexive character of policy research – and here its links with critical knowledge (e.g., political economy) becomes essential.

Finally, critical research knowledge draws upon the Hegelian and Kantian traditions to reflect on power relations and justice, as well as what we know, what we don't know, and what we might know. We view critique as an essential phase or moment of research, and the kind of knowledge it produces can promote re-evaluation, rethinking, and redirection. It facilitates adjustment of our understanding of both ongoing professional research but also of the social world more generally – which is always in transition. Critical knowledge can thus feed into professional knowledge as well as policy knowledge. Its major “collision” tends to be with administrative knowledge, where clients are reluctant to have their goals challenged by critical researchers – mirroring again a continued tension in the knowledge produced by media research.

If we apply this matrix very briefly to the newer terrain of social media, we can note that there is a concerted effort not just from our field but from many disciplines to generate professional knowledge about its character, use, consequences, and contingencies. At the same time there is a massive generation of administrative knowledge geared to deploying social media for marketing and advertising. There is also some policy knowledge being produced by researchers, but we would suggest that far more is needed, especially to gird the reflexive discussions about how such media are to be supported, regulated, made accountable, and how the freedoms associated with them are to be protected. Critical research is emerging, addressing not least questions of political economy, such as ownership, control, and financing, as well as problems to do with surveillance, privacy, and copyright. These initiatives can interface quite neatly with policy research, but hopefully they will also impact on the professional knowledge generated – which often reflects the perspective of the dominant paradigm. We can expect these force fields to be with us for some time.

NOTES

1 For a more detailed account of these controversies see Splichal, 2012.

2 Texts – “literary and visual constructs, employing symbolic means, shaped by rules, conventions and traditions intrinsic to the use of language in its widest sense” (Hall, 1975, p. 17) – are artifacts that we use to make meaning of and from; they include not only printed documents but also radio and television programs, movies, documentaries, shows, websites, and many others.

3 Under the lead of Paul Lazarsfeld, the project was launched at Princeton University in 1937 and later moved to the Columbia University's Bureau of Applied Social Research.

REFERENCES

Adorno, T. W. (1945). A social critique of radio music. Kenyon Review, 7(2), 208–217.

Adorno, T. W. (1969). Scientific experiences of a European scholar in America. In D. Fleming & B. Bailyn (Eds.), The intellectual migration: Europe and America, 1930–1960 (pp. 338–370). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communication research. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Blumer, H. (1948). Public opinion and public opinion polling. American Sociological Review, 13, 542–554.

Bojd, D. M., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210–230.

Bücher, K. (1893/1901). Industrial evolution. New York, NY: Henry Holt.

Burawoy, M. (2007). Open the social sciences: To whom and for what? Portuguese Journal of Social Sciences, 6(3), 137–146.

Calhoun, C. (Ed.). (1992). Habermas and the public sphere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society. London, UK: Routledge.

Childs, H. L. (1965). Public opinion: Nature, formation, and role. Princeton, NJ: D. Van Nostrand.

Durkheim, E., & Tarde, G. (2008). The debate between Tarde and Durkheim. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 26, 761–777.

Fairclough, N. (2010). Critical discourse analysis (2nd ed.). Harlow, UK: Longman.

Ferment in the field [Special issue]. (1983). Journal of Communication, 33(3).

Fuchs, C. (2011). Foundation of critical media and information studies. London, UK: Routledge.

The future of the field I [Special issue]. (1993). Journal of Communication, 43(3).

The future of the field II [Special issue]. (1993). Journal of Communication, 43(4).

Gallup, G. (1938). Testing public opinion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 2(1), 8–14.

Gallup, G. (1957). The changing climate for public opinion research. Public Opinion Quarterly, 21(1), 23–27.

Gallup, G. (1971). The public opinion referendum. Public Opinion Quarterly, 35(2), 220–227.

Gripsrud, J., Hallvsard, M., Molander, A., & Murdock, G. (Eds.). (2010). The idea of the public sphere: A reader. Lanham, MD: Lexington.

Habermas, J. (1989). Structural transformation of the public sphere. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Hall, S. (1975). Introduction. In A. C. H. Smith et al., Paper voices: The popular press and social change, 1935–1985 (pp. 11–24). London, UK: Chatto & Windus.

Hall, S., et al. (Eds.). (1980). Culture, media, language. London, UK: Hutchinson.

Halloran, J. D. (1981). The context of mass communication research. International Commission for the Study of Communication Problems Document No. 78. Paris: UNESCO.

Hardt, H. (1979). Social theories of the press: Early German and American perspectives. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Horkheimer, M. (1936/1976). Tradicionalna i kritička teorija/Tradizionalle und kritische Theorie/. Belgrade, Serbia: BIGZ.

Just, N., & Puppis, M. (Eds.). (2012). Trends in communication policy research. Bristol, UK: Intellect.

Klapper, J. (1960). The effects of mass communication. New York, NY: Free Press.

Knies, K. (1857/1996). Der Telegraph als Verkehrsmittel: Über der Nachrichtenverkehr überhaupt. Munich, Germany: Reinhard Fischer.

Kracauer, S. (1952–1953). The challenge of qualitative content analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16(4), 631–642.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962/1970). The structure of scientific revolutions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lang, K. (1979). The critical functions of empirical communication research: Observations on German–American influences. Media, Culture & Society, 1, 83–96.

Lang, K., and Lang, G. E. (1983). The “new” rhetoric of mass communication research: A longer view. Journal of Communication, 33(3), 128–140.

Lasswell, H. D. (1949). Why be quantitative? In H. D. Laswell et al. (Eds.), Language of politics: Studies in quantitative semantics (pp. 40–54). New York, NY: George W. Stewart.

Lasswell, H. D., et al (1949). Language of politics: Studies in quantitative semantics. New York, NY: George W. Stewart.

McQuail, D. (2010). McQuail's mass communication theory (6th ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Merton, R. K. (1945). Sociological theory. American Journal of Sociology, 50(6), 462–473.

Mosco, V. (2009). The political economy of communication (2nd ed.). London, UK: Sage.

Oboler, A., Welsh, K., & Cruz, L. (2012). The danger of big data: Social media as computational social science. First Monday, 17(7). Retrieved July 10, 2013, from http://www.firstmonday.org/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3993/3269

Osborne, T., & Rose, N. (1999). Do the social sciences create phenomena? The example of public opinion research. British Journal of Sociology, 50(3), 367–396.

Plato (360 BCE/1901). The Republic of Plato (B. Jowett, Ed. and Trans.). Retrieved July 10, 2013, from http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.html

Porter, T. M. (1995). Trust in numbers: The pursuit of objectivity in science and public life. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schäffle, A. (1875). Bau und Leben des sozialen Körpers. Tübingen, Germany: H. Laupp'schen.

Schiller, H. (1975). The mind managers. Boston, MA: Beacon.

Smythe, D. W. (1981). Dependency road: Communications, capitalism, consciousness and Canada. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Smythe, D. W., & Van Dinh, T. (1983). On critical and administrative research: A new critical analysis. Journal of Communication, 37(2), 117–127.

Splichal, S. (2012). Public opinion and opinion polling: Contradictions and controversies. In C. Holtz-Bacha & J. Strömbäck (Eds.), Opinion polls and the media: Reflecting and shaping public opinion (pp. 25–46). Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tarde, G. (1897/2000). Contre Durkheim à propos de son Suicide [Contra Durkheim on his Suicide]. In M. Borlandi & M. Cherkaoui (Eds.), Le suicide – un siècle après Durkheim [Suicide – a century after Durkheim] (pp. 224–225). Paris, France: PUF.

Thompson, W. (1824). An Inquiry into the principles of the distribution of wealth most conducive to human happiness: Applied to the newly proposed system of voluntary equality of wealth. London, UK: Longman.

Tönnies, F. (1922). Kritik der öffentlichen Meinung. Berlin, Germany: Julius Springer.

Weber, M. (1910/1979). Speech to German Sociological Association. In H. Hardt, Social theories of the press: Early German and American perspectives (H. Hardt, Trans.) (pp. 174–184). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.