21

Transmedial Aesthetics

Where Form and Content Meet – Film and Videogames

ABSTRACT

Videogames may offer new ways of telling stories and engaging players by virtue of their interactive characteristics, but do they offer any differences from cinema in terms of content and representation? While videogames are formally distinctive, this chapter shows that, to a lesser or greater degree, they nonetheless draw on vocabularies developed within cinema. Through an examination of Final Fantasy XII, as well as with reference to a range of other games, this chapter analyzes how, through an interlacing of form, content, and representation, videogames work in convergent and divergent ways to create for the player an emotionally resonant aesthetic experience.

Convergences and divergences between film and videogames have been the subject of some quite considerable analysis within the context of recent academic work, conducted mainly within the emerging field of digital game studies. Within this is a pivotal engagement with the way that form shapes content. This relationship is the focus of this chapter, which further takes as a central analytic example the game Final Fantasy XII (Square Enix, 2006). While by no means all academic work focused on videogames is conducted by those with a scholarly interest in film, several game studies academics have a film studies background, including myself, Diane Carr, Geoff King, Bernard Perron, Bob Rehak, and David Surman. What is remarkable is that many existing analyses focusing on the distinctions of form and content between videogames and film stress that the former should be regarded as a distinctive form in their own right, despite videogames also being a screen-based audiovisual medium. In early work on videogames, scholars such as Espen Aarseth, Jesper Juul, and Markuu Eskelinen expressed an understandable concern that the interest shown in videogames by film scholars would entail games being subsumed as a subsection of film studies. Old theories and arguments used in the analysis of film would simply be rehashed without paying due attention to the considerable differences and unique features of digital games. Further, the fear was that the use of film studies models might stultify the broader process of exploring what digital games could potentially become. To their minds, these interlopers came along with a risk of dismissing what is specific to videogames in terms of their formal and ludological features, their design and construction, and the unique experience of playing them. This is not, however, evident in most of the existing work conducted on games from those with a film studies background. The consensus of opinion is that, unlike film, videogames are rule-based, place emphasis on player agency, and are governed by ludological rubrics. This is clearly a formal distinction, but does it make for a distinction in terms of content? In many ways form and content are co-dependent, yet in some regards the same tropes simply become remediated.

While it is crucial to note the formal divergence between film and videogames, it is nonetheless the case that videogames do draw on film form and content (as well as other media) in a variety of ways. Award-winning game designer Peter Molyneux has said that cinema provides game makers with good and well-developed models for creating engaging characters and for making more meaningful and emotionally resonant gameplay features.1 As well as showing that game designers often look to cinema for inspiration (and, indeed, in some cases aspire to the financial and critical successes of cinema), this comment provides an example of David Bolter and Richard Grusin's influential concept of remediation (2000). Games are not made in cultural isolation; many features of existing media inform the strategies used in new media, but the exchange is far from simple and straightforward. This means that both form and content are likely to be informed by established media formations.

Critical perspectives used within film studies, including approaches drawn from other disciplines but tailored to the task of addressing film, can be used to highlight convergences of form and content between videogames and film. Close formal analysis of the type used in film studies to analyze the structure, impact, and meaning of the moving image is of particular use in understanding games, and implicitly formal analysis is also considered with content (story and character in particular, rather than representation and reception). Formal and content analysis can also be applied to the ludic and participatory elements offered by a game, even if these core elements are what make videogames qualitatively different from other media. Other types of approaches used in film and media studies to analyze reception, the types of investments and interpretations that audiences and individual viewers bring to the text, are, however, very useful to help understand the qualities and affordances of games themselves, their role in contemporary culture, and indeed why certain formal and content formations have proved popular and affective with audiences. Film-based approaches can also be used in a comparative way to ascertain significant differences between the two media. Models and methods derived from art studies, media studies, social science, philosophy, psychology, and psychoanalysis developed for the analysis of screen-based media can also prove helpful to the process of understanding more fully some of the pleasures offered by games, pleasures that needed explaining in terms of the interplay between form and context, as well as the ways in which videogames are embraced by broader social, cultural, and ideological contexts. That is not to say that there is no need for the development of bespoke approaches that emerge from the particular questions videogames provoke, and there is room, of course, for the analysis of representation. There are some aspects of videogames that do indeed demand new concepts and models if we are to understand better their particularities, influences, and potentials in terms of both form and content. This analysis focuses not on representation, however, but on the relationship between form and content.

While videogames have various formal, content, and industrial links to film (industrial convergence is addressed later on), the centralization of the ludic, player agency, and interactive components, as well as the actual business of designing and making them, means that videogames diverge in some significant ways from film. As a means of highlighting some of these differences and to show the particularities of videogames, I will focus on one recent game, citing other examples where they are relevant. This is a game that has, it should be said, a closer relationship to film than many other existing games or game genres. While games such as Tetris or Bejewelled cannot be described as having either narrative or cinematic camera-based features, the game chosen here has a highly developed storyline, uses many cinematic-styled cut-scenes both in game and “movie” sequences, and the franchise from which it is drawn includes two films: Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001) and Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children (2005). As such, is it a useful game with which to demonstrate that some videogames share certain features with film in formal and content terms. I keep my analysis to the very opening scene of the game to gain depth. As such, this is not an essay about the game itself but as a means to look at the relationships between form and content in the context of a very cinematic game. Even in a videogame that is clearly inspired by cinema and that uses content formation found across recent screen-based popular fiction, it is, as we shall see, divergent in terms of its form, design, and the type of experience offered in some important and innovative ways. In order to better understand videogames, we have to take account that content is linked to form in a special way. The link is the player. Without considering play – how the player accesses the text through his or her participation in the game – we cannot consider either content or form, as both are intrinsically linked to what the player does.

Aesthetics of Convergence

After loading the first game disk into my PlayStation 2, I sit on the sofa and watch as the opening scenes of Final Fantasy XII (Square Enix, 2006) unfold on the television screen, the game controller lying limply in hand. The busy, blink and you miss something introductory montage sequence has all the characteristics expected from a sophisticated and high-budget digitally animated film, and it is designed to be both visually impressive and inviting. The prominent use of widescreen format is inherent to this, representing one of the ways that games and film converge as screen-based media in terms of form and content. More so than 4 : 3 aspect ratio, widescreen format, first developed for cinema, lends itself admirably to the task of creating the type of visual spectacle that gives the effect of a panoramic vista. The format encourages, as David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson note, “horizontal composition,” and it was first used in genres “in which sweeping settings were important” (2001, p. 212). The game's opening cut-scene takes full aesthetic advantage, shaping form and content, of the commercial success of widescreen television in the domestic arena (see Figure 21.1). An unanchored camera moves with moderate speed downwards through white fluffy clouds evoking immediately a sense of freedom and movement (to view the opening scene see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L20Ph_IC514&mode=related&search=). A small skyship comes into view at the bottom of the screen, further widening the scope of the on-screen; the camera follows the skyship's swooping trajectory more speedily through the air and over a fantastical sunlit cityscape. Cut to birds in flight, which travel in a contrary direction to the earlier trajectory of the craft, drawing the eye in a different direction and enhancing the sensation of freedom and motion. Strange skycraft that resemble the fantastical, antiquated, steam-punk flying machines of Terry Gilliam's The Adventures of Baron von Munchausen (1988) float weightlessly above the city, while smaller craft whiz between them. Sky and earth are tied together through editing and framing into one space – providing an efficient invocation of the game's world – which is a product of form and constitutes a basic component of game content. Using the principle of cinematic attraction, the saturated colors glow with jewel-like intensity, the detailed textures provide visual delight and add further to the sense of epic-proportioned scale, again characteristic of the game's particular content design.

Figure 21.1 Widescreen, panoramic vistas.

Through a montage of ever-moving dissolves, various vistas of the landscape come into view. A boy looks out to sea, the camera still in flight, never settling to allow quiet contemplation of any one image. We are taken on a fly-mation journey tourists in a new land. A change of mood: a close-up of heavy armored bodies introduces a counterweight to the previous fluid lines of flight; war darkens the screen and a skycraft plummets to the city, showering flame and debris, its downward motion in sharp contrast to the soaring horizontal axis of the previous and subsequent sequences. A small skycraft curves away into the horizon, creating a huge depth of field, followed by a range of vignettes using in-game graphics of fantastical creatures fighting, fleeing, intercut with sky battles and explosions, while huge, strange, and clearly magic objects throw bolts of light across the screen. All is movement – cinematic form and “world” content bound in unison. The pace then gears down for a short while to show close-ups of key characters in the game, each also talking in animated ways, gesticulating, eyes trained horizontally on their interlocutors, the camera still moving; more creatures are fleeing; the pace and sense of movement, signifying war-induced panic, increase. A clear-eyed anime-inspired boy with hair waving in the breeze looks upward. All this is accompanied by a full orchestral soundtrack that changes mood in accordance with the fleeting images, formal features providing what is often called in the game industry “flavor” (a term that implies content design).

The types of camera angles used, the framing, the character and location exposition are all features born of form and content that we might expect from a mainstream film (the vignettes of characters have perhaps more in common with televisual formats, however). The fluidity of the sequence, the vistas that would be impossible to create in a live-action pro-filmic context, are enabled because this is digital animation (informing form and content, therefore): the camera is not a “real” camera but a totally fictional creation that celebrates the freedoms of perspective offered by the highly flexible fabrications of digital animation. The meticulous attention to movement and light, and the geometries of the visual choreography, are all content designed to capture and delight the eye. And, as with film, only to look on and enjoy what is seen is demanded from the player.

Figure 21.2 The spectacle of procession.

The game title appears after a few minutes of black screen, a result of the game software loading into the console's memory in the next sequence. This represents something of an interruption that would be unlikely in cinema, but it reminds viewers that they will become, in a short time, players – an “X to skip” icon appears in the corner of the screen, a subtle textual indication that this is a game and not a film. A second cinematic sequence ensues, which moves us to the events on the ground, and a date and location appear in scripted text. This sequence is far more narratively loaded than the previous one. Some of the images seen at the start reappear, but this time they are given a stronger context (content forged through formal patterning). A royal wedding procession appears, peopled by a host of human and fantastical creatures including what look like white rabbits playing drums. This draws on, but dwarfs in its scope and spectacle, the type of impressive historical pageants seen in the biblical films of Cecil B. DeMille or Joseph L. Mankiewicz's Cleopatra (1963), to which are added the fantastical stylistic qualities of anime (see Figure 21.2), a mode of animation based often on comic books popular in Japan. The scene also recalls the celebratory processions of the Star Wars series, which are used to showcase Industrial Light and Magic's special effects and helped to establish the company's centrality to the cinema of digital attractions, a status to which Square Enix also appears to aspire. (The game itself is something of an homage to Star Wars.) The young couple, wide-eyed, flawless, and idealized, are married by an elderly priest, making use of a well-worn metaphorical image of Hope. Rapidly the scene changes, as the recently wedded boy-man expresses his intent to go to war and military processions take the place of the joyous wedding scene, providing an entry into the common war-based rhetorics of games and fantasy fiction more generally. Movie-style credits overlay the scene, present in the corner of the screen rather than prominently centralized, as occurs conventionally in film. Their presence underlines the game's clear aspiration to cinema, marking authorship in a similar way. While company logos are ubiquitous, opening credits have occurred rarely in videogames, although recently they have appeared in high-profile games that have similar production costs to Hollywood films.

A battle ensues, shown taking place alternately in the sky and on land, a series of aerial shots, close-ups, and midshots unfolds, all in third person except for a first-person shot out of the window of a small skycraft; as elsewhere in these opening sequences the framing and editing grammar of cinema is used. In the thick of battle the newly wedded boy-man is slain. To add to the melodrama, his wife sheds a single tear, bowing her head as we are shown, through a classic shot-reverse shot, her lifeless young husband shrouded in flowers in his coffin – again drawing on a well-worn image of melodrama designed to evoke pathos. This montage sequence then clearly aspires to epic and melodramatic registers: the viewer learns of the power struggles in play, the personal tragedies and heroic action that set the particular milieu of the world. The cost of producing these scenes for a film would in all probability mean that they would be made longer and be placed more centrally in the story. We are presented with a world in which the viewer is being invited to become a player. While it is undeniably cinematic, it is perhaps more intense and condensed than would commonly be the case if this were live-action film – game form shaping content.

What we have here is something that looks more like an advert for a film than a film itself (and it is common for attention-grabbing cut-scenes to be made before games go to market to exhibit at industry shows). The effect is to entice the player into the game's world, pulling focus on historical events that provide the context for gameplay. The use of montage provides an economical and evocative sense of the complex world that we are about to enter into as players. While these scenes offer all the audiovisual pleasures of cinema on a grand scale, they also have the function of keying the player into the game world. With the world clearly in chaos, sunlight replaced by war-torn gloom, a series of scripted text screens appears. Some overlay a map of the world showing different states, and a voice, later revealed to be the antagonist in the main game plot arc, tells us what we can read in flowing script of the perilous state of the kingdom of Dalmasca caught in the struggle between two great empires: Archadia in the east and Rozarria in the west. Dalmasca has surrendered to the might of Archadian armies. This breaks the rule of cinema – to show and not to tell – but the encouragement to read the screen here heralds the fact that the player will be required frequently to read scripted text in the game and pay attention to what is written. Written information is part of game form (and genre-based), certainly, but it is also clearly content – a rhetorically designed device that players of such games will expect and which aims to immerse the player further into the virtual space of the game.

During these opening sequences the game controller lay quietly in my lap, although held in such a way that it could be ready quickly for any required action, the presence of the controller acting as a reminder that I am “watching” a game and not a film. The transition from being a viewer, with time to let the eye linger on the luscious graphics, to becoming a player is gently introduced. The game prompts the player to press a key to scroll through the scripted text that explains some of the game's back story. This is another reminder that this is a game and that games require players to respond to cues through correctly timed button presses on the controller, enabling the story to unfold and allowing actions to be taken. Thus, a primary difference between the modes of engagement offered by games and film comes into view, and this difference clearly affects form and some aspects of content. Again the screen goes black, but this time it opens on a blurred, reverse iris point-of-view shot of one of the soldiers seen in the earlier cut-scene (this blonde, self-possessed warrior is named Basch and is designed through his bearing and look to attract the player into the game space).2 There is a scripted cut (edit) from first-person view back to an image of an anime-style boy, on the verge of becoming adult, who is returning to consciousness after being injured. An edit back to his point-of-view locates us in the skin of this character and subject to the attention of Basch. As well as a very cinematic storytelling device, the blurred point-of-view shot, along with the preceding scripted text/map sequence, is used to help mask, at least to some extent, the transition between the high-resolution pre-rendered graphics of the opening cut-scene to real-time graphical rendering – technical concerns shaping content, therefore. Real-time graphical rendering is required in videogames because the on-screen image changes in accordance with the players-characters' movements and actions – again, technical concerns shape the appearance of content. This marked shift in graphical fidelity is something that would not happen in cinema or even in anime, and the transition marks this out as a game rather than a film.3 It also acts as a call to action for those who are attentive to the visual grammar that is specific to videogames.

I take up my controller in anticipation, now eager to play. But before I am able to act in the game, I watch as Basch fights then kills several heavily armored opponents – whetting the player's appetite to get stuck into the action. The scene provides an exemplar of what will be expected of the player-character shortly and emphasizes the immediate dangers of the location. Basch then speaks to the player's character, who we learn is named Reks. Basch communicates with the player in two different modes: he speaks to the player as player and also communicates through scripted text that appears at the base of the screen. His speech is always in character, but the scripted text is not, even though it is in first person. At times this accords with the fictional diegesis, but at others it tutors the player in the use of the controller, in how to interact with non-player-characters and how to fight. This acknowledges form but shapes content. For example, “Basch: Do you see the mark above my head? That's a Talk icon. You can talk to any character showing one of these.”

Direct address to the viewer is used very occasionally in mainstream film, for example at the start of The Libertine (2005). However, it is more common within science fiction and fantasy films that deal with complete fictional worlds as a means of communicating to viewers the often complex pseudo-historical factors that have led up to a present situation (The Lord of the Rings films, for example). Games of the type that also take place in fictional worlds, such as the Final Fantasy series, use this technique, but it is also aimed to tutor the player. There is a mix of diegetic and extra-diegetic information that would be very unusual in other media, but here is content driven by the participatory form of games. (Diegesis and diegetic are terms used in film studies to denote that which is integral to the given fictional world; non-diegetic or extra-diegetic refers to that which is present in the text but not directly anchored in the fictional world. Non-diegetic music, for example, is not “played” or heard by characters.) This dual register is echoed in the co-presence of speech and scripted text and might appear “odd” when seen together to those unused to playing games who are more familiar with film. Noting such co-presences again highlights how games differ from film in aspects of their content because of an underlying difference of form, specifically, the requirement of participation and the need to tutor the player in the particular design of a given game's participatory interface (the interface then has to be factored into the content as well as the form of games). If a player does not actively initiate a discussion with the character that Basch has asked the player's character to speak to by correctly using the game's interface, nothing more will happen; this is in stark contrast to film, where there is no requirement on the part of the viewer to perform any action to keep diegetic events in motion.

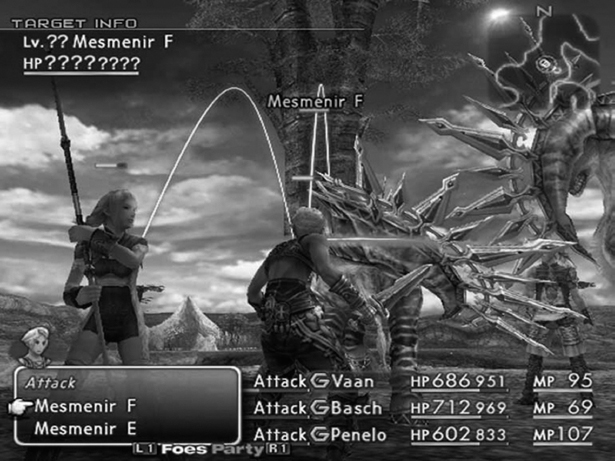

Other extra-diegetic text and graphical features appear on the screen and can be regarded as content that is designed to aid the player in playing the game. Some are situation-specific menus that allow players to initiate fights or choose which enemy they target. Engaging in turn-based combat, which the player is required to do throughout the game as a core activity, produces “health bars” above enemies' and party-members' heads (these important feedback mechanisms are part of the game's content, telling the player about the status of the fight, and diminish as player-characters make a strike with their in-game weapons). Numbers also appear for a few moments to indicate the percentage number of hits; occasionally a word such as “block” or “parry” splashes across the screen, making more sense of the differentiation of hit points achieved in combat. Graphic-based colored arcing lines indicate to the player which characters are attacking and being attacked (see Figure 21.3). Such “feedback” content enables players to make informed choices about what they do. Are the foes too strong? Should they run beyond the reach of these opponents? Or should they change opponents? A fight is therefore busy with information and action. While the informative features are anchored to the actions taking place in the diegesis, they are also in a filmic sense extra-diegetic, but all constitute content and are born of game (and, indeed, generic) form. This demonstrates how, in terms of content, games marry together diegetic and extra-diegetic features to form a gestalt, to use Craig Lindley's useful term (Lindley, 2002),4 between the practical features or rules of gameplay and the fictional world created by the game. Jesper Juul makes a similar point, stressing the intersection between games as rules and games as fiction: “fiction cues the player into understanding the rules, and rules can cue the player into imagining a fictional world” (2005, p. 6). It is the combination of fiction (diegesis) and rules (exhibited through extra-diegetic features) that can be regarded as constituting form and content, that enable players to be agents within the fiction, making videogames fundamentally different from film (even if the representations of gender and war are derived from existing and normative traditions). The gestalt formed in the relationship between game and player means that rules are inhabited and transcended, often through what the player brings in terms of emotional and imaginary investment to his or her character and the game's world. This only occurs because of the particular nature of the form and its shaping of content.

Figure 21.3 Graphic-based colored arcing lines indicate to the player which characters are attacking and being attacked.

Therefore, during the game's tutorial sequence, players are on a learning curve, being shown how to read content as part of what they are expected to do to progress through the game. Continuing with the unfolding of events in the game, more storyline is delivered and Reks finds the King of Dalmasca dead, learning that Basch killed him for his willingness to surrender Dalmasca to the Empire. Reks is once again wounded, this time by Basch (shaping up as the antagonist of the piece). As he falls into unconsciousness – it is unclear whether or not he has died – he calls the name of Vaan, his brother. We soon learn that it is not Reks we will play through the rest of the game but Vaan. This represents a surprising twist in a game of this type, one that is inimical to game format, as, unlike films, where multiple views are afforded and a switch of point-of-view is common, games often anchor the player's point-of-view to that of one character who represents us in the world of the game, as with Lara Croft in the Tomb Raider games. While some games are not so arranged, in real-time strategy and management games for example, continuity of point-of-view is common within role-play and action-adventure games and helps players to gain a sense of identity within the world of the game. The shift into the skin of a new character accords with the game's cinematic aspirations. It also has a narrative and dramatic function, nascent at this point of the game, yet suggesting to the player either that the death of Reks will motivate Vaan to turn against the Empire or that he may need to be rescued. Through a series of scripted text screens, which shifts the time frame forward, we learn, erroneously, that Basch has been hanged as a lesson to all those who would oppose the Empire. Vaan, through whom the player now acts, is living hand-to-mouth in Dalmasca under the occupation of the Empire, but clearly aspires to being a warrior, the fate of his brother unknown both to him and to the player. As with many other fictions, this state of equilibrium is unlikely to last, but it will allow the player to get used to the game's interface and its particular vocabulary of actions. This again provides an example of content shaped by the demands of the game's participatory form.

The numerous cut-scenes in Final Fantasy XII work with the audiovisual grammar of cinema through framing, editing, and camerawork (even if this is rather hyperbolic in a manner similar to high-octane action-movie trailers). During gameplay sequences, however, the framing is anchored to the movements of the player-character, the camera positioned slightly above and behind the shoulder of the character, tracking its movement seamlessly. This is a product of game form, framing aspects of content. Unlike earlier games in the series, Final Fantasy XII does not use pre-rendered backgrounds. This means that the camera can be moved independently to some extent to facilitate a more flexible point-of-view, required for checking for objects or enemies and to get a better view of the terrain without having to move the character in the game space (which might in some situations attract unwanted aggression). However, the camera does pivot from a fixed point, which retains a link between the player and the character's perspective on the game world. This marks a significant difference from the more mobile framing conventions commonly used in cinema and plays a profound role in determining the nature of the game's content.

There are some considerable differences between the way that stories are structured and delivered in games and films, although there are some points of crossover. The tightly knit structures of cause and effect often found in cinema do, however, suit the feedback formations that characterize digital games. While it is rare, for example, for repetition to occur, as it does commonly in games (try and try again!), content formations might, however, be closer between games and films. With its greater than usual use of cut-scenes, Final Fantasy XII borrows from cinema as well as from tropes developed within the fantasy genre. Well-established fantasy iconography and characterization, with their tendency to value heroic acts in battles against evil, lend an established generic flavor to the game's content.5 As a result of the aspiration to create a game with an epic and complex narrative, the story structure of Final Fantasy XII resembles, at least to some extent, the more flexible narrative structures of the type commonly found in recent Hollywood blockbuster action movies. In this sense, Final Fantasy XII is more cinematic than most other games. Such films tend to include sequences of action and spectacle that are often said to temporarily suspend narrative in favor of other more visually located pleasures. This might suggest that the structure of popular action-based film narratives has become more like that of games: the long chase sequence near the start of Casino Royale (2007), which involves much jumping and running, provides an excellent example. It is also possible that the frequent presence of game tie-ins with films has promoted this so that films can be translated easily into game format, which suggests a move toward what might be termed an aesthetic of convergence.

Narrative as Form and Content

Narrative and story have attracted a great deal of debate amongst videogame scholars. The tools employed to analyze the structure of narrative in mainstream films offer some use for the analysis of story in games, but in many ways they fail to deal adequately with the media-specific manner in which games structure and deliver story. Story is of course constituted in terms of content and form. Models of narrative found in mainstream films are more similar in games that Jesper Juul (2005) calls “games of progression.” Such games, Final Fantasy XII included,6 require the player to follow a predetermined course of narratively framed action and have a more linear construction as a result. “Games of emergence,” however, such as management games, real-time strategy games, MMOGs, and role-playing games, have a broader range of options and potential outcomes available to players that make these games more complex and open. These games, therefore, are either not concerned with narrative or are far less plot driven than games of progression. This is clearly a distinction of form, but these differences also influence content in certain respects.

In many games of progression, narrative is shifted more to the sidelines than is the case with most mainstream film. This is the case even in a game like Final Fantasy XII, which has a highly developed and complex story. But that is not to say that it is not important as a means of contextualizing what the player does in the game. Moment-by-moment developments, many of which are focused on achieving localized tasks, usually gain narrative importance through their position in the wider frame. Within games of emergence, however, the emphasis is often on what Lisbeth Klastrup (2003) has called the “player-story”: the story that emerges through the choices, trajectory, and investments of the player. In The Lord of the Rings Online, for example, players are offered an environment that provides a host of means through which game characters can be developed by players in imaginative ways, interacting in-character with other players should they choose to do so and tailoring play style accordingly. In addition, players are provided with the means to make some significant choices about what they specialize in and they can choose from a list of character types to best suit their gameplay preferences. The game's content (the design of the spaces, the items in the game, the broader mythos and ethos of the game) then supports the player-story, providing props for role play, for example. In addition, various choices are offered that allow the player's character to develop different types of skills. This content is of form, but it is content in a diegetic sense.

To some extent Fable (2004) combines features of games of emergence with games of progression: although there is a set path of progression, the player can, as in most role-playing games, choose to specialize in different modes of combat (e.g., spells, melee). Player choices make for some differences in the experience of the game, although they do not provide the breadth of divergence found in many other RPGs. Importantly, then, the scope for player intervention differs in games, and this is an issue not just of form but also of content. Final Fantasy XII provides the player with a good deal of freedom of character customization: you can develop Basch into a thief or Vaan into a mage. This flexibility is designed to suit different playing styles, placing greater influence on the player-story where the character of the game content is designed to be shaped by the player, but is often based on cues provided by the game's content (as well as being made possible by the game's participatory form). In all these cases, however, a comparative analysis between the structure and delivery of narrative in film and games can be used effectively to highlight convergences and divergences between the two media in terms of form and content. Significantly, narrative has a more central, organizing role in film than in games. Many games have little or no narrative, and where they do, players can choose whether or not to attend to or make imaginative investment in the game story, or even whether or not they regard their own experience of playing a game in story terms. Some players, for example, might simply choose to skip all the cut-scenes in Final Fantasy XII, preferring instead to get stuck into playing the game. From a design perspective, what many fantasy-based role-playing games aim to do to make for a compelling and immersive experience is to enable players to make use of the participatory nature of games to build into the content and form provided, something that makes players feel that their experience is uniquely based on their particular choices.

Affect, Movement, and Time

I turn now to what I regard as a significant aspect of the relationship between film and games and form and content in games that has hitherto received somewhat scant attention, and which builds on points made in the “Aesthetics of Convergence” section above. This absence is likely to have resulted from the centralization within game studies of debate around the relative merits of ludology and narratology. This has tended to polarize the field. As a consequence, many authors, perhaps to avoid censure, have been intent on highlighting the ways that games diverge from film rather than considering points of possible convergence. Nonetheless, the goal of generating affect, by which I mean making what happens in a fiction matter to player/viewer/reader, is common to both media. Gilles Deleuze's (1986) writing on the affective qualities of cinema, informed by Henri Bergson's (1971) work on time, provides a productive means of considering affect and bodily sensation in relation to games. It also provides an impetus for ascertaining how games create affect differently from film in terms of form and content. The goal to generate diverse affective experience underlies the use of a host of different techniques. Indicative of these are: suspense, anxiety, tension, relief, frustration, anger, pity, delight, surety, and fear. In this sense, representation is often subtended to affect rather than cultural agendas around the politics of representation. Games regularly make use of the types of techniques used in cinema to generate affective experience. Due to space constraints I will focus on two indicative examples. The first focuses on music and the second on graphics and gameplay – in terms of content and form. These examples stand in for a multitude of possibilities.

Both films and games use music and sound effects as important formal and content means of setting a scene or event's emotional pitch. Music and sound often tell us how to read what occurs and also provide a very immediate way of evoking particular physical sensations. As players travel through the area known as the Shire in The Lord of the Rings Online, they encounter eight types of music that are representative of the English countryside and a kind of rural authenticity. Each of these musical styles is inspired by folk music. They are divided into jaunty foot-tapping tunes played on acoustic instruments (flutes, violins, and guitar) and more plaintive and wistful tunes, mostly played on single instruments (these are mainly non-diegetic but at times diegetic – in the village of Stock, musicians can be seen playing on the bandstand outside the village tavern, and most taverns have minstrels). In combination with the green and pleasant rural landscape of early summertime, with hobbit homes nestling in the safety of small hills, the soundscape composed of folk music, ambient sounds such as bird song, a gentle breeze blowing, and domestic animals is clearly designed to evoke a desirable pastoral idyll. Representing something of “good” and of value, it is designed to make the player care about its fate when it becomes imperiled. When traveling in the Shire, there is a strong sense of peacefulness and nostalgia for an uncomplicated life (Figure 21.4), a representation that is clearly motivated by a desire to engage the player at an emotional level. The same types of images, sounds, and music (similar style and instruments, although with different intellectual property content) are also used in the early scenes of Peter Jackson's The Lord of the Rings film trilogy.

The tranquility and comfort of the folk music is counterpoised dramatically with the music associated with spaces or beings designated as evil or threatening. In the Old Forest region of the game (Figure 21.5), sustained unresolved chords, accompanied by eerie, from-the-depths trombone sounds and tympani, provide an immediate and highly disturbing sense of tension and threat. Exciting it might be, but the representational scheme is designed to motivate the player to fight to conserve in narrative terms the quotidian life of hobbits. Similar types of musical arrangements are heard in the film with similar effects. In each case music, both as content and operating representationally, forms a gestalt with the story – the valuable “small cares” existence of hobbits is threatened by evil forces. In conjunction with jarring and ominous music, the labyrinthine design of the Old Forest, in which the hapless traveler is apt to become lost, with dangerous trees that uproot themselves to kill the unwary, is far from a comfortable and relaxing place to be. Indeed, many players complain in “out-of-character” chat about the place and its perils, which to some extent demonstrates the way in which music, gameplay, reception, and graphics are knit together to produce strong affect. This affect is heightened because of its juxtaposition with the Shire – which is giving potency in terms of content and representation, in much the same way as in the film and the novel, but form means that the player has a real place, real choices and actions to take, in this virtual space.

Figure 21.4 The Party Tree in the Shire: pastoral idyll.

Figure 21.5 Attacked in the Old Forest by a warped oak.

Whether it is melodic and bright or dissonant, jarring, and dark, music has powerful affective qualities, making it a potent aspect of content and, in some regard, representation. As Henri Bergson has written, the rhythm and measure of music suspend “the normal flow of our sensations and ideas by causing our attention to swing to and fro between fixed points, and they take hold of us with such force that even the faintest imitation of a groan will suffice to fill us with the utmost sadness” (1971, pp. 14–15). Music is affective because, he says, it impresses feelings upon us rather than expressing them, arousing sympathy in our minds “just as a mere gesture on the part of the hypnotist is enough to force the intended suggestion upon a subject accustomed to his control” (p. 16). Toward the goal of producing affect, music is indispensable: the movements of music can move us profoundly, far more easily than visual representational means alone. In broader game history terms, moving from small cartridge memory to CD and then to DVD format has made significant shifts in the amount and complexity of audio in games; the availability of greater space for sound files means that games are now better able to mimic the quality and complexity of sound and music in cinema, which provides thereby an increasingly potent means of making games more meaningful. Music is therefore a powerful component of a game's content and representational schemes, and is often tied into gameplay activities, for example, hearing a threatening, lethal “warped oak” coming your way before you are able to see it.

In the opening cut-scene sequences of Final Fantasy XII, described earlier, there is a heavy emphasis on visual movement that is designed not only to arrest the gaze but also to give viewers through virtual means a physical sense of unanchored movement.7 The pursuit of this affective quality drove the design of the content. Through the mobile, airborne camera, aided by the creation, through editing and framing, of a sense of speedy movement in a huge depth of field, a sense of disembodied freedom, of soaring, of not being weighed down and fixed to matter or point-of-view is strongly present. This is emblematic of both the theme and the broad ethic of the game: fight to free the world from stultifying oppression. Movement, travel, is life and stasis, death.8 After the cut-scenes end and play begins in earnest, the player-character becomes earth-bound, limited in where he or she can move by various hard and soft boundaries including non-player characters (NPCs) that represent the oppressive force of the Empire. Vaan, Reks, and, by implication, the player are locked into constrained situations by the programmed organization of the game's space and physics as well as the conditions of the diegetic world. This content ties into the very form of games. These constraints determine the player-character's movements and actions. The player-character is in multiple senses determined (overdetermined in the psychoanalytic sense) to break free and learn how to move and act according to will without clumsy restraint. Form, representation, and content have a pleasing unity, therefore. In short, the goal – the imagined ideal – is unrestrained agency. Significantly, very early on in the game, Vaan passionately proclaims his intense desire to become a flyer, which is finally fulfilled in the last scene of a successful play-through. This ties very neatly into what I regard as the extended metaphor established at the start of the game of flight as emblematic of freedom. Also very neatly (under the badge of fortuitous serendipity), it dovetails with Deleuze's own investment in what he calls “lines of flight,” which is used to mean deterritorialization (no longer earth-bound, no longer bound) as a form of resistance to leaden and restrained hegemonic organizations of subjectivity, thought, experience, and life in general. I don't for a moment believe that the authors of the game are intentionally making their game through reading Deleuze; instead, across a range of boundaries including cultural ones, both game and Deleuze use the poetic notion of flight as a metaphor for freedom.

Could the same felt meaning be achieved in a film? Yes, but because of differences of interactive game form, this extends into other dimensions. In the context of a game, through the character, the player actively bumps into various boundaries that are experienced as diegetic limits on play and agency, as well as limitations of the programmed actions that the character can make. This gives, as I have said elsewhere (Krzywinska, 2002), a very direct and felt experience of the way that external forces and bodily realities limit personal agency. It is representational and operates through content, but it is form that provides this hands-on experience of constraints on agency. In the cinematic cut-scenes we are given images and, importantly, sensations of what it is to be free – the cinematics act, therefore, as emblematic of an ideal “free” state unhindered by the restraints of embodiment (unachievable but relative and thereby informative structurally, textually, and affectively). The opening cut-scene seems therefore to represent the sphere of the imaginary and thereby imbues the rest of the game with a certain sense of realism, even if it is represented graphically in anime terms. As well as acting as a counterpoise to the particular embodiment and determinations we experience during gameplay (and in real life), this is also indicative of the high regard that the game designers have for cinema and their own aspirations to achieve the heights of what they think cinema has offered viewers. Herein lies a damning indictment of the way that games are regarded culturally and industrially as a lower form of activity than filmmaking.

In the game, movement is far more restricted and less fluid than within the cinematic cut-scenes, yet, paradoxically, within these the player is required to do nothing but watch, even as they might capture the imagination and locate the viewer in the soaring realm of the fantasmatic. Taking up suggestions from Bergson (1971, 2004) and Deleuze (1986), the passivity within which we are encased when watching a film results in a high degree of affective intensity. Because we cannot act, the energy that is generated turns inwards, strengthening through the very nature of the virtual affect. If this is the case, then what of games? If we are provided as players with the capacity to act, to have some agency to prevent Vaan from dying in a fight, for example, then is there less affect in play than if we were simply watching him have a fight in a film? Speculatively, I believe the answer is no. Here we cut to the heart of the differences between playing a digital game, doing things in real life, and watching a film. Games require the player to make tightly measured movements in response to what occurs on screen. Agency is condensed within these tiny controlled movements. If we get out of hand, as it were, then we fumble our actions. The act of having to control what we do extremely carefully, to reproduce certain key presses in a given order in response to the stuff of content, means that energies are still folded back on themselves by virtue of the control, or mastery, the player needs to exert. Erroneous play (leading to repetition and stasis) or success (leading to a state of flow and a sense of moving forward through time) both feed into the register of interactivity to create intensity. Frustration ensues when we don't control what we do absolutely, a type of self-blaming frustration that I, at least, have never felt when watching a film. Even if one is frustrated with a film or television show, it is rarely on account of one's own bungled action. If we do get things right, self-satisfaction is the result – the type of affect that makes us feel very good about ourselves, and again that type of affect in a truly physical sense is not something I have experienced when watching a film. Content and representation have, then, a supporting role in the formal player-centric context of games.

Nonetheless, playing a game demands close reading from players, close reading of content and representational schemes, if they are to make the right kind of responses. If you don't pay attention to events, or proxemics and kinesics (the positioning of characters/objects and the way they move) when watching a film, then only potential meanings are lost, whereas in games you, the player, lose far more, and it's personal. Games therefore are architected from learning curves that tutor the player in how to read closely the cues provided by a situation and how to react in cognitive and physical terms.

Games and films are different entities, yet as screen media the boundaries between them are far from sealed. Games borrow from film, films borrow from games. Players bring what they know of film to games, and with the recent trend for tie-ins between games and films, viewers are apt to bring to the experience of watching film their knowledge of games. The Lord of the Rings Online provides an indicative example. Imagery established within Peter Jackson's films informs the game and players role-play often using representational character and situation cues from those films (indeed, it appears that more players use the films to inform their presence in the game's world than the books on which the franchise is based). With the Final Fantasy franchise, the games came first. The two films consolidate the game worlds across different, but related, media, and they use crossover imagery between iterations of the franchise. Those who have played the games are very likely to read the films through their experience of the games; intertextuality is therefore a property of content, representation, and form. Popular culture has of late embraced world-based fictions such as these because the format lends itself well to multi-authored cross-media franchises. These become playgrounds for numerous writers and artists, as Henry Jenkins (2006) has said; a context is set up and they are able to make up multiple stories and experiences within the context of the world. Given that convergence is fast becoming core to the business strategies of the contemporary media industry, fictional, virtual worlds offer up a recognizable brand with particular flavors that make use of the various characteristics of different medial forms that can be used to produce a whole range of products to make for greater market penetration. This dovetails all too neatly with increasing technological and industrial convergence, which depends on formulating devices to create long-stay, regularly spending audiences and consumers. As such, the spheres of games and media are merging ever closer in terms of content and representations, even though games and films have a range of formal differences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge Anna Powell's Deleuze and the Horror Film (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), as reviewing Anna's book reignited an interest in Deleuze and Bergson. Thanks to Douglas Brown, David Surman, and Esther MacCallum for their thoughtful and informed comments on drafts of this chapter.

NOTES

1 Peter Molyneux in conversation about the influences that informed the design of Fable 2 (Lionhead) with MA Digital Games Theory and Design students at Brunel University London, UK, March 2007.

2 Basch's character recalls the historical figure of Yuki Hideyasu (1574–1607). Pastiches of Edo grand narratives are a staple of Japanese cinema and also filter into Japanese role-playing games (RPGs). (My thanks to David Surman for pointing this out.)

3 The Final Fantasy games have often been criticized for the gulf between cut-scenes and in-game graphics, but with each incarnation and with developments in graphics processing, the difference is lessened.

4 I differ from Lindley's argument here in that I maintain that narrative and gameplay form a gestalt in their own right, because they work together through the game fiction and rules.

5 In Massively Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs) cut-scenes are rarely used except in opening expositions. Guild Wars is, however, a notable exception. Some games have dispensed with cut-scenes completely, preferring instead to deliver story through gameplay, as is the (often celebrated) case with Half Life (1998).

6 Although often thought of as an RPG, Final Fantasy XII has a lot in common with action-adventure games.

7 As mentioned above, I point the reader to http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L20Ph_IC514&mode=related&search= to view the opening cinematic sequences of the game.

8 This is echoed in the motif of nethercite, the reification of magic (a gift from the gods), created by the convergence of magical tradewinds, versus manufactured nethercite, a creation of the Empire that sucks magic from the world.

REFERENCES

Bergson, H. (1971). Time and free will. London, UK: George Allen & Unwin.

Bergson, H. (2004). Matter and memory. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications.

Bolter, J. D., & Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation: Understanding new media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bordwell, D., & Thompson, K. (2001). Film art: An introduction (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Deleuze, G. (1986). Cinema 1: The movement-image. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Juul, J. (2005). Half-real: Videogames between real rules and fictional worlds. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Klastrup, L. (2003). A poetics of virtual worlds. Retrieved May 2, 2007, from http://hypertext.rmit.edu.au/dac/papers/Klastrup.pdf

Krzywinska, T. (2002). Hands-on horror. In T. Krzywinska & G. King (Eds.), Screenplay: Cinema/videogames/interfaces (pp. 206–224). New York, NY: Wallflower Press/Columbia University Press.

Lindley, C. (2002, June 6–8). Conditioning, learning and creation in games: Narrative, the gameplay gestalt and generative simulation/interactive storytelling. Proceedings of the Computer Games and Digital Cultures Conference, Tampere, Finland.