16

Imagination and Censorship, Fiction and Reality

Producing a Telenovela in a Time of Political Crisis

ABSTRACT

Telenovelas seem an unlikely arena for political discourse. In 2003–2004 the Venezuelan telenovela Cosita Rica aired, in the middle of the country's political crisis and its deep polarization around the figure of President Hugo Chávez. In addition to the usual love stories, Cosita Rica included characters who were metaphors of the protagonists on the political scene (one character's story was an allegory for Chávez), plots that reflected the embedding of politics in Venezuelans' everyday life, and a storyline that mirrored the presidential recall referendum of August 2004. This chapter examines how Cosita Rica was produced in a time of political turmoil. It is an open window into the life span of telenovela production; through it we are able to observe the writing and the mise en scène processes and how the commercial demands of the genre, the audience's readings, the comments of the entertainment press, and the government's censorship played a fundamental role in Cosita Rica's production.

Telenovelas, long considered by some to be “the most watched television genre in the world” (McAnany & La Pastina, 1994), are melodramatic serials that focus on a central story of heterosexual love plagued with misunderstandings and obstacles. These melodramas seem an unlikely arena for political discourse. However, political commentary has been present in several Brazilian telenovelas (La Pastina, 2004; Porto, 1998, 2005; Straubhaar, 1988), and in Venezuela's Por estas calles (On These Streets) (Hyppolite, 2000; Márquez, 1999).

In 2003–2004 the Venezuelan telenovela Cosita Rica took the stage, in the middle of the country's political crisis and deep polarization around the controversial figure of President Hugo Chávez. Cosita Rica both straddled and blurred the line between fact and fiction through its complex and realistic characters – some of them allegories of political personalities (including Chávez) – and through its multiple plots framed by Venezuela's political and socioeconomic crises. The telenovela was broadcast in the space of 11 months (September 30, 2003 to August 30, 2004), which included the difficult period that lead to the presidential recall referendum of August 2004 and the referendum itself. Simultaneously mirroring and criticizing reality, Cosita Rica achieved high ratings despite the audience's political polarization.

This chapter examines how Cosita Rica was produced in a time of national political turmoil. My study is a contribution to media production scholarship because, in a media industry characterized by secrecy, it opens a window into the lifespan of telenovela production. Through this window we are able to observe the writing, staging, and acting processes in the context of commercial demands for high ratings, the audience's responses to the program, the comments of the entertainment press, and the government's censorship rules. All of these elements played a fundamental role in the production of Cosita Rica.

Theoretical Framework and Methods

Even though there is still a shortage of cultural studies of media industries in the US, this research area has been growing at a fairly steady pace in the last years (see Mayer, Banks, & Caldwell, 2009). Forerunners in this tradition, such as Todd Gitlin's (1983) Inside Prime Time and Julie D'Acci's (1994) Defining Women, embrace a broad conception of culture as a “site of social differences and struggles” (Johnson, 1986/1987, p. 39). For Richard Johnson, cultural studies is a project that stresses lived experience, legitimizes popular culture as a valid research topic, and focuses on conflicts over meaning in order to “to abstract, describe and reconstitute in concrete studies the social forms through which human beings ‘live’, become conscious and sustain themselves subjectively” (p. 45). Several theorists have tried to model the project to this end: Stuart Hall (1980); Johnson himself (1986/1987); du Gay, Hall, MacKay, and Negus (1997); and D'Acci (2004).1 All of them include production as an essential element in the study of media and culture.

However, a cursory glance at the cultural studies literature shows a disparity between the number of studies that focus on media production and the amount of research that examines media texts and/or audiences. In general, scholars show a marked preference for the “decoding” aspects of the communication process, while the “encoding” side seems somewhat neglected (as argued in D'Acci, 2004; Kellner, 1995; Levine, 2001; Ytreberg, 2000), or treated as its opposite (MacKay, 1997). This shortage of cultural studies of media production is the result of several factors. First, scholars often choose to study reception rather than production because there is a generalized perception that it is not easy to gain access to media production sites and personnel. Second, D'Acci (2004) argues that the seminal collection Cultural Studies (Grossberg, Nelson, & Treichler, 1992) contributed to American cultural studies' move toward text-centered approaches and foci. This focus, writes Douglas Kellner, helped produce an imaginary divide between cultural studies and political economy, even though

[i]nserting texts into the system of culture within which they are produced and distributed can help elucidate features and effects of the texts that textual analysis alone might miss or downplay. Rather than being antithetical approaches to culture, political economy can actually contribute to textual analysis and critique. (Kellner, 1995, p. 6)

Although I do not disagree with Kellner, I would add that, in order to study the telenovela industry, we must also study processes of media production as cultural phenomena. Beyond economic relations and organizational structures, the processes themselves are “assemblages of meaningful practices that construct certain ways for people to conceive of and conduct themselves in an organizational context” (du Gay, 1997, p. 7). Cultural studies of production assume that media and culture are inextricably linked, since “culture is concerned with the production and the exchange of meanings – the ‘giving and taking of meaning’ – between the members of a society or group” (Hall, 1997, p. 2). Telenovelas demonstrate these exchanges of meaning par excellence. There is constant negotiation between the writers, the director, the production team, the actors, the audience, and the institutional staff that participates in the social formation of the genre. As Jesús Martín-Barbero (1993) argues, the telenovela is a site of “mediations” between production, reception, and culture. The genre thus offers a perfect example of how production and consumption are deeply articulated (Quiroz, 1993).

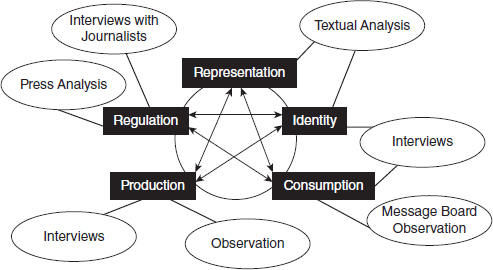

My own cultural study of the production of Cosita Rica is organized largely around the “circuit of culture” model (du Gay et al., 1997) and intends to show how meaning is created and negotiated through processes of production, representation, identity, consumption, and regulation (see Figure 16.1). Each of these processes reveals how the meanings associated with the telenovela are produced, negotiated, and contested. Each one informs the cultural study of production in a more complete way. Hence I studied production processes through 40 hours of individual interviews with Cosita Rica's actors, directors, and producers, and through 30 hours of interviews with head writer Leonardo Padrón. I supplemented these interviews with 200 hours of participant observation on the production set of the telenovela and by watching several episodes with Padrón, observing his reactions. Representation and identity processes were examined through a textual analysis of the telenovela's 245 episodes. I further studied identity and consumption processes via 40 individual and group audience interviews, open-ended email questionnaires, and sustained observation of Internet message boards devoted to Cosita Rica. These gave me insights into the class and political differences between the various audiences of the telenovela. Finally, I looked at regulation processes by interviewing entertainment reporters and analyzing the extensive press coverage (778 news stories) of national current events and the political implications of Cosita Rica. Therefore, although this chapter focuses on the production of the telenovela, the circuit of culture reminds us that production processes are linked to representation, identity, consumption, and regulation.

Figure 16.1 Study theory and methods (based on du Gay, Hall, MacKay, & Negus, 1997 and their concept of the circuit of culture).

Some scholars have criticized circuit models for being reductionist and for limiting the way we approach the study of cultural products (see Grossberg, 1997); but I agree with D'Acci's response to this criticism:

A circuit model doesn't hawk a formulaic approach to TV studies; rather it underscores that we cannot start from ground zero each time we embark on a new project, and that explicitly working from the scholarship of the past (scholarship that has contingently delineated and analyzed various dimensions of production, reception, cultural artifacts, and socio-historical contexts) is the best way to structure our current inquiries and our pedagogical practice. (D'Acci, 2004, p. 431)

Context: Reality, Crisis, and Television

Venezuela's Political Crisis

On February 4, 1992, Venezuelans woke up to the surprising news that an attempted coup was in progress. The country, deemed as Latin America's most stable democracy at the time (Blanco, 2002), had not experienced a similar event since 1958, when the last dictator, Marcos Pérez Jiménez, had been deposed. The attempt was short lived. By the end of the day the insurgents had surrendered, then President Carlos Andrés Pérez was back in his office at Miraflores Palace, and the captured leader of the coup appeared on national television – a sign that the government was again in control. A paratrooper with the rank of lieutenant, Hugo Chávez, looked with aplomb at the camera in front of him as he serenely accepted sole responsibility for the coup's inception and failure. Chávez asked his followers to depose their weapons and surrender, since their goals could not be achieved por ahora (for the time being). This por ahora television moment changed the fate both of Chávez and of Venezuela (Villegas Poljak, 2002).

Chávez became president of Venezuela in a landslide election in 1998. Soon after, the party system suffered a severe breakdown as he drafted a new constitution and reinvented institutions to further his left-leaning Bolivarian Revolution. Four years later political polarization settled in Venezuela, tainting and pervading all aspects of political, social, economic, and cultural life. Chávez is a messiah for his supporters and a devil for his opponents. He is adored and feared. His supporters allege that the opposition has not allowed him to govern. Opponents argue that he is an incompetent autocrat.

In April 2002, after massive street protests against his government, Chávez was briefly toppled in a business-organized military coup, only to be brought back to power 48 hours later by the military. The return to power followed the mobilization of Chávez supporters – chavistas – who clamored in the streets of Caracas for their president's return. In December of the same year the opposition, structured under the umbrella organization Coordinadora Democrática, orchestrated a two-month strike that embraced the oil industry. This strategy proved to be a huge miscalculation. Chávez survived the work stoppage and fired the oil industry employees who had participated in it. The economy suffered a severe blow. Exchange controls were enacted, many businesses closed and unemployment figures rose to new heights, as the economy contracted by 29 percent (Forero, 2003).

After the failed strike, the opposition tried a legal alternative: to activate Statute 72 of the constitution, which allows for a mid-term recall referendum of the president. (In other words it allows voters to remove their president from office before the expiration of the presidential term.) The thorny path to the referendum began in November 2003, with a petition drive to gather the necessary number of signatures to request the referendum. Three months later the National Council of Elections (CNE, which stands for Consejo Nacional Electoral) deemed 1.3 million of these signatures “invalid”; street violence ensued. Then the CNE implemented a process through which the invalid signatures could be “repaired.” Finally, in June 2004 the presidential recall referendum process was activated, much to the opposition's delight.

The historic referendum took place on August 15, 2004 after a short but intense political campaign, which was plagued by mutual accusations of abuse and deceit. Chávez stayed in power. His supporters and opponents stayed in their respective ideological camps. The polarization created then in Venezuelan politics and society persists until today.

Chávez and the Media

From the beginning of the crisis, the Venezuelan mass media played a crucial role in this story. Chávez entered the political stage through television. As a presidential candidate, he was supported by almost all media owners and conglomerates (Hawkins, 2003). However, as business, professional, and elite circles became increasingly disenchanted with the new president, they started fearing the effects of the Bolivarian Revolution. The honeymoon ended and the tone in the media changed gradually, but steadily. In his weekly allocution to the nation, “Aló, Presidente” (“Hello, President”), Chávez repeatedly lashed out at privately owned media. He once called media moguls “horsemen of the Apocalypse” and asked the Venezuelan people to distrust them. By the time of the 2002 coup, the private media were unequivocally opposed to Chávez and had assumed an overt political role.

In June 2003, when the first episodes of Cosita Rica were being written, relations between the government and privately owned media were extremely contentious. The latter were in critical financial straits due to the national strike. Their content was unmistakably oppositional. Out of fear of the wrath of chavistas, print media offices and broadcast stations were heavily guarded. Reporters wore bullet-proof vests and other anti-riot gear on a daily basis. There were documented cases of threats and physical violence against journalists, and even against entertainers (Tremamunno, 2002). The president appeared regularly on cadenas – mandatory public radio and television broadcasts.2 During these sessions he derided all private media and threatened to control their content.

Polarization and Telenovelas

Venezuela is a major player in the international telenovela market (Mato, 2005). In the last decade, the Venezuelan telenovela industry has both struggled with and been shaped by the internal political forces of polarization, government-media belligerence, and media regulations that have characterized the presidential terms of Hugo Chávez. Two private television networks – RCTV (Radio Caracas Televisión, owned by the Phelps-Granier family) and Venevisión (owned by the Cisneros family) – are Venezuela's main telenovela producers and exporters. For the last 50 years they have battled with each other fiercely, in a ratings war that has defined Venezuelan television. The latter has also been marked by the changing relationship between these private networks and the Chávez government. Cosita Rica's production took place in this defining context.

Telenovelas have a stronghold on Venezuela's prime-time television. Many Venezuelan telenovelas follow the traditional format of la telenovela rosa – a love story about a heterosexual couple in which both partners have to overcome obstacles and intrigues in order to achieve happiness together. The two main characters usually come from different socioeconomic backgrounds; therefore their love story is also a story about socioeconomic advancement. Simplistic, one-dimensional, Manichaean characters are linked in a main storyline, in which love always wins over evil (Cabrujas, 2002). In contrast, telenovelas de ruptura break with this traditional format, as they include social and cultural issues taken from Latin American reality. These telenovelas present complex characters, which are both ambiguous and unpredictable, and their storylines combine personal and social problems in a narrative fiction that attempts to chronicle and critique social actuality, speaking to the audience in terms of a shared reality (Martín-Barbero & Rey, 1999). Cosita Rica belongs in this latter category.

Cosita Rica's Production3

It is almost impossible to identify the precise moment in which a telenovela begins to be conceptualized. The creative spark occurs in an imperceptible place in the author's brain (or heart); it is the result of his experiences and talent, and it becomes eventually the ideas that will shape the story. It is far easier to pinpoint the event that leads to the long-term business deal that places a telenovela on the screen.

Cosita Rica's author is the Venezuelan poet and writer Leonardo Padrón. In his case, the creative trigger for his many telenovelas has usually been the city of Caracas and the many characters that inhabit the streets of this fascinating, glamorous, and dangerous metropolis, which is also home to 25% of the Venezuelan population. Cosita Rica began like many business deals with a lunch meeting. Padrón's trajectory as an experienced and successful telenovela writer meant that he did not have to compete with other authors to capture the attention of network executives.

Over that lunch, Padrón explained the general concept he had in mind, the characteristics of the main protagonists and their love story, and outlined some of the subplots. The author's thesis for Cosita Rica consisted of two stories: “The tale of an immense love and the story of the lack of affection between the political extremes in Venezuela” (Leonardo Padrón, June 18, 2003). His first audience for this story was the network's president, its vice-president, and the person in charge of dramáticos (dramas). These network executives liked Padrón's proposal. The conversation then veered from general ideas to particular deadlines – when to turn in the first scripts, when to begin shooting, when to go on the air – and to other particulars: set locations, names of possible protagonists, cast members, and the executive producer and general director who would realize the scripts. Padrón got the green light to start the project of putting his ideas into practice.

Telenovelas, much like soap operas, are made to fit existing talent pools and tight budgets. As he designed characters and storylines, Padrón imagined who would be the best actor for each role. The network negotiated with those artists and their agents. Once Padrón had confirmation that an actor/actress was on board, he would tailor the character specifically for that person. Meanwhile executive producer Consuelo Delgado and general director César Bolívar explored possible locations for the story in Cosita Rica. The budget of a Venezuelan telenovela is considerably lower than that of its Brazilian and Mexican counterparts.4 Therefore Delgado and Bolívar had to be creative about choosing locations. For example, all the scenes scripted for a college coffee shop were actually videotaped in the network cafeteria. Gradually Cosita Rica acquired its eventual shape. Actors signed their contracts and met with Padrón to talk about their characters, and a small number of episodes were written. In August 2003 production began. In September Venevisión broadcast the first promotions. Finally, on September 30, Cosita Rica entered the ratings battle.

How were the writer's ideas transformed into episodes that aired at 9 p.m. every Monday to Saturday? With the exception of Sundays, Padrón and his team of three writers (the dialoguistas) wrote at least one episode of the telenovela every day. The time span between each finished episode and its broadcast was originally two weeks in September 2003, but this process shortened to three or four days as the telenovela's finale approached. This is the main reason why telenovela writers have no time to rest. They absolutely must generate one episode per day, in an inexorable routine:

It's an overwhelming creative system. [. . .] Your inspiration must be on a schedule. You have to create a story during nine months that seem to last forever. You write a pile of 12,000 pages, 5,500 scenes, and 200 hours of dramatic tension. [. . .] You can't wait for the arrival of the muse. You must wake her up and bring her to work on time. (Padrón, 2002, p. 51)

Cosita Rica's writing process lasted over one year and was not limited to “office hours.” Very early each morning, Padrón outlined (diagramaba) the next episode by creating a list of scenes. This is a delicate process. It requires a clear sense of dramatic structure and of the audience's tastes regarding the storyline and the characters. In a good episode outline (diagra), the writer moves the story from one cliffhanger to the next and creates linkages, so that the story holds the audience's attention without losing sight of the characters' essential traits. Padrón divided the scenes among his writers, saving for himself the ones that were key to Cosita Rica's argument and dramatic structure. Several hours later, when all the scenes had been written, Padrón proceeded to assemble, revise, and polish each episode, taking particular care of his “left-hand margin” notes for the technical crew and cast members in each shoot. Throughout this process he consulted with his writers and with Delgado. Shortly before dusk Padrón emailed the definitive version of the episode, approximately 40–50 pages with 25–30 scenes, to Delgado.

In her capacity as an executive producer, Delgado studied the episodes with the eyes of the person in charge of “making the writer's ideas and dreams come true” (Consuelo Delgado: June 11, 2003). For her, each episode was a long list of props, sets, talent, and equipment requirements. General producer Carolina De Jacovo then converted each script into the shooting schedule – la pauta – a daily timetable organized by scenes, which governs each studio and shooting location and details everything needed: sets, props, actors, director, and production assistants. Script and pauta were then copied and given to every single person involved in the production. Actors usually highlighted their lines as they learned them, and they quickly decided on a strategy for their scene(s).5 Personnel in the departments that handled props, sets, and wardrobe also worked to be ready for the upcoming shooting schedule, which began very early each morning and ended late at night on most days.

After all the scenes in an episode were videotaped, the episode itself went to the editor's booth, then to the music department, and finally to the post-production department, where it was finalized and promotional previews were prepared.6 Meanwhile Padrón stayed on top of as many production details as he could manage. He analyzed, for example, the promotional calls and argued for a number of commercial breaks that would not weaken the dramatic structure of his story. He also worried that President Chávez would interrupt the broadcast with one of his many cadenas and carefully examined the ratings, trying to figure out the recipe for staying on top without betraying his telenovela's essence. At home, Padrón watched the final version of his text on his television screen. He focused on the unavoidable gap between the script and the production. He analyzed the actors' performances, which became a frequent source of inspiration. Before going to bed he would work a bit more: “After I watch the episode, I usually pre-outline the diagra I will work with the next day” (Leonardo Padrón: April 27, 2004). And that is how each day in the lifespan of Cosita Rica ended: with a glimpse of what would come the next day.

Cosita Rica's Flight

Padrón frequently compared the daily struggle of writing and producing a telenovela with flying an airplane on a very long flight. I use the same metaphor to describe some of the key moments in Cosita Rica's journey, which will illustrate the everyday life span of a telenovela from a production standpoint, without losing sight of the articulations with representation, identity, consumption, and regulation.

Like an aircraft, a telenovela must take off with enough power to reach cruise altitude and speed in an adequate amount of time. It is also essential to keep the plane on the air through storms and turbulence until it is time to land softly. Ratings and shares, which are “God and currency” for any commercial television business, determine the duration of the flight.

September 30, 2003–March 2004: Takeoff and Flying at Cruise Altitude in a Turbulent Country

On the evening of September 30, 2003 Cosita Rica took off. And, even though network Venevisión had been consistently losing the prime-time ratings war for the past two years, it took Cosita Rica only a couple of weeks to own the first place. The audience enjoyed the telenovela's balanced mix of love, melodrama, reality, humor, and political commentary. By the end of October Cosita Rica was flying at cruise speed and altitude. Its main competitor, RCTV's La Invasora, had been definitely relegated to second place in the audience's preference. The entertainment press covered and commented on Cosita Rica extensively.7 Padrón, his writers, the cast, and the production team worked feverishly without major interruptions or problems. And by February, the network's decision makers, ecstatic with the telenovela's success, asked Padrón to extend it from the planned 180 episodes to 240.8 Since the writer felt his story had still many possible developments, Padrón agreed to the extension, while production anticipated the continuation of a smooth flight.

In contrast, Venezuela was increasingly agitated as Chávez's opponents gathered the necessary number of signatures to trigger a constitution-based recall referendum of the president. By the end of February 2004, the National Council of Elections announced that 1.3 million of the collected signatures were invalid; this triggered a week of violent street protests in Caracas, which were aggressively squelched by the National Guard and kept people away from their work places. Production stopped that week, and it was necessary to broadcast reruns for several days. When the telenovela returned during the first week of March, the episode included a monologue by the teenage character Nixon. He was the story's occasional narrator, representing the voice of young Venezuelans who face an uncertain future in a polarized country. In a voice-over accompanied by real images of the street protests and by the National Guard's ensuing repression, Nixon said:

I'm very sad because of my country. Venezuela used to resemble the word happiness. But now everything is different. There is fire in the streets. People are shooting each other. I can't feel the breeze from the Avila because oxygen now stings, like eyes itch with tear gas.9 Some of my friends' parents have disappeared or are dead. Everyone has a stone in their hand . . . or in their minds. Everyone's angry. One of our teachers told us that this is the way wars begin. I'm very scared, even though my dictionary has words that could help us become the country we once were: democracy, freedom, tolerance. But there's a word I've been searching for and I can't find: peace. I'm 15 years old and I live in the country that grownups built. However, these days nobody is behaving like an adult. Instead, they act like rabid dogs. Is it possible that it's easier to kill ourselves than to respect each other? I'm 15 years old and I want someone to give me back my country. Someone . . . or everyone . . . A country that resembles peace . . . peace . . . please . . . (Episode 113)

In general, audience members for and against the president approved these words, which resonated with their recent experience (Acosta-Alzuru, 2011). Mirroring political reality, however, was not an easy road for Padrón. The audience liked occasional editorializating and enjoyed the use of metaphor, as in the case of the charismatic, verbose, and polarizing character Olegario Pérez, which Padrón wrote as an allegory of President Chávez (ibid.). But, when the telenovela re-created a notorious and widely reported case of authority and physical abuse by the National Guard (Benzaquen, 2004), my study participants were divided in their appreciation, and not by their political position. Some enjoyed watching the sequence, arguing that it “helped people comment what was happening in the country” (AMELIA, 27). Others thought it was “too much” (ANDREA, 35) and “too similar to the tragic events in the streets” (MONICA, 46). The network received many phone calls from viewers who warned that, if the telenovela was going to become another newscast, they would stop watching it. Such was the nature of the tightrope that Cosita Rica walked between reality and fiction, between being a mirror and providing entertainment.

April 2004: A Two-Airplane Race and los Niños de la Calle

In April, Venezuelans took a break from political unrest, as the CNE decided to implement a process to “repair” the signatures deemed invalid. The television competition, however, heated up at 9 p.m., when RCTV premiered its new telenovela, Estrambótica Anastasia, and won the ratings the next ten days in a row. Padrón had been preparing for the new competition. His strategy was to wait a few days and then to exploit the dramatic conflict of Cosita Rica's favorite story of young love (the historia de amor juvenil)10 (Acosta-Alzuru, 2007); in the story, identical twin sisters separated at birth – one poor, the other rich – fall in love with the same man.

In a plot reminiscent of Mark Twain's The Prince and the Pauper, María Suspiro and Verónica meet for the first time in their early twenties and decide to exchange places. They are opposites, two sides of the same coin:

María Suspiro is war. Verónica is peace. María Suspiro is hyper. Verónica is serene. The first is joyous. The second is melancholic. María Suspiro is intuitive. Verónica is rational. To me they're both luminous. María Suspiro is the blazing sun of high noon and Verónica is the light of sunset. Neither one is night. (Leonardo Padrón: May 8, 2004)

María Suspiro falls in love with the luxury of her sister's life, and Verónica falls for her sister's boyfriend, Cacique, who does not know that his girlfriend is really two different women. As the plot progresses, the relationship between Cacique and Verónica heats up. Their “chemistry” surpasses the television screen. The love triangle is set in such a way that, by the time the public realizes that Cacique is (unknowingly) really in love with Verónica, they already love María Suspiro's exuberance too.

Ten days after the premiere of Estrambótica Anastasia, in a heavily promoted episode, Cacique finds out that María Suspiro has an identical twin sister and that the two women have been exchanging places. Even with a forced 10-minute interruption for Chávez's allocution, ratings soared to the highest point that Cosita Rica would ever achieve. Not even its final episode topped the numbers of that pivotal evening. Cosita Rica regained its first place. The writer's strategy had worked.

The fact is that when a story has broadcast 150 episodes, the audience has its favorite characters and stories. It would be senseless to navigate against the audience's likes and dislikes. [. . .] When the telenovela faces a strong rival, I must underscore Cosita Rica's strengths. This is what I'm doing with Cacique and the twins, and it's working. (Leonardo Padrón: April 27, 2004)

In April, in addition to the fierce ratings war, Cosita Rica's production had an incident with the Chávez government, which was related to a subplot focused on the high number of abandoned and runaway children and adolescents who live in the streets. Known as los niños de la calle (“street children”), these youngsters have dropped out of school and do not count on family support. They survive among the filth and insecurity of Venezuela's largest cities as beggars and/or petty thieves (Márquez, 1999).11

Street children have a presence in Cosita Rica in a plot in which 15-year-old Nixon, who lives in one of the poorest sectors of the city, meets a group of niños de la calle. Despite their aggressive and seemingly disdainful attitude, their physical and emotional hunger gives away their needs and disturbs Nixon in profound ways, as these youngsters place him in the unusual situation of being the most “privileged” in the group. Nixon's mother, an unemployed, single parent, gets involved and organizes fundraisers on the street children's behalf. In this way Nixon and his mother become the conscience that reminds the viewers that, in spite of these children's ubiquitous presence in the streets, it is easy to become desensitized to their plight and to forget them, even when we are seemingly looking at them:

NIXON (VOICE-OVER during the New Year spectacular fireworks in Caracas): Like every year, we were all betting on a great New Year and a country that finally resembles our dreams. [. . .] The only thing that saddened me was to think of how my friends from the streets were doing at that time. I know that at a happy time like New Year's, the whole country forgets their existence. Maybe in this coming year there will be a President that will remember them. Hopefully . . . (Episode 75)

The political overtones of this storyline reached a climax when Nixon and his friends decided to take advantage of a political rally to voice the needs of los niños de la calle. Nixon climbs the stage, takes the microphone away from a politician who is delivering a trite speech, and speaks out on behalf of his friends:

NIXON: You would think los niños de la calle are dumb and can't speak. I say this because it seems to me nobody is listening to them. Today I speak for them, as if I were one of them. Grownups, don't mention us until you learn to look at us without disgust. The only thing we want is a place that could be called home and something that resembles a school. We don't want to hear any more lies. We don't want to listen to any more unfulfilled promises. (Episode 145)

The network edited Nixon's monologue. In the original script, the youngster also said: “Mr. President, don't mention us anymore in your speeches. Members of the opposition, don't use us in your political propaganda.”

The editing of this monologue was the first instance of prior restraint related to Cosita Rica. It was caused by an incident that occurred while shooting these scenes. With every permit required by law, the sequence was shot in a quiet street across from the army's social entity, Club de Suboficiales. A few minutes after young actor José Manuel Suárez (who played Nixon) said his lines, Minister of Defense General Jorge Luis García Carneiro arrived at the location:

He was very irritated and upset. First, he kicked one of the guards of the Club de Suboficiales because he had allowed the telenovela to videotape there. Then, he unplugged some of the network's equipment and yelled that if we didn't leave the premises in 30 minutes, he would detain everyone. (Leonardo Padrón: April 17, 2004)

In addition to ordering the editing of the monologue, network executives scolded executive producer Delgado for her choice of location for this sequence and warned Padrón about the political color of this particular plot. This first instance of self-censorship by Venevisión was a sign of alarm and heralded changes in the network's political position.

May 2004: The Electric Storm

In May, Venezuelans opposed to Chávez “repaired” their signatures to recall the president and waited, while the CNE slowly audited and tallied the signatures. In Cosita Rica new characters appeared, creating new dramatic plots, solving some of the older ones, and giving the entertainment press more fodder for stories and gossip columns. Padrón worked on ways to return his protagonists – Diego and Paula C. (played by actors Rafael Novoa and Fabiola Colmenares) – to Cosita Rica's center stage. In the ratings competition, the telenovela stayed firmly in first place. In spite of all these positive developments, May was a stormy month for Padrón and for Cosita Rica's female protagonist Colmenares.

Measured in ratings and shares, the emphasis placed on the twins' plot at the end of April had worked successfully. However, the audience felt a bit disoriented, as it perceived that the protagonists' story was now second in importance, a transgression of the telenovela codes. “I feel the protagonists are now in the sideline” (ANA, 49). There was some discomfort among the cast too. One actor told me anonymously: “In this telenovela the protagonist code has been broken. Last Tuesday we won the ratings war with an episode that did not feature the female protagonist at all.”

On May 4 an upset Colmenares met with top network executives and threatened to resign unless her character regained the importance of a protagonist. They promised her that they would talk to Padrón. However, the next day, when the network's president and vice-president met with the writer, they did not mention the topic of Colmenares' possible resignation, focusing instead on the successful strategy of elevating the volume to the twins' storyline (Leonardo Padrón: May 5, 2004). Padrón had already written a sequence of episodes focused on the main love story that included protagonist Diego interrupting Paula C.'s wedding with antagonist Olegario.12 The plot was promising and the production team worked long hours for the mise en scène of these episodes, which were videotaped in a country estate outside Caracas.

Colmenares, however, had already talked to the press. Entertainment reporter Marlene Castillo wrote on May 11:

Fabiola, more depressed and disappointed than upset as she watches her character lose its rank of protagonist, presented her resignation to Venevisión top executives, who did not accept it with the promise of a “reconsideration” that would revalue her role to what it used to be. (Castillo, 2004b, p. 20)

The next day other reporters and gossip columns echoed the news of Colmenares' resignation. But, on May 13, the respected daily El Nacional reported that “Padrón denies Fabiola Colmenares' resignation” (Silva, 2004, p. B10). Entertainment reporters who had written about the resignation as a fait accompli reacted angrily:

Leonardo Padrón denied Fabiola Colmenares' resignation. It isn't the first, nor is it the last time that this happens. But to deny us when we're supported by the truth bothers us. [. . .] Colmenares DID resign. (Castillo, 2004c, p. 19)

When the promotions for the upcoming wedding episodes were broadcast, the press assumed this development as confirmation that Colmenares had indeed resigned and Padrón had been “scolded” by network executives who were appeasing the actor (Sepulturero, 2004c).

Paula C.'s interrupted wedding with antagonist Olegario produced good ratings, although significantly lower than those of Cacique and the twins.13 Venevisión's executives were happy, even though Cosita Rica's distance from RCTV's Estrambótica Anastasia gradually decreased when the protagonists were finally together. What mattered was that the Padrón–Colmenares storm seemed to be over without having any effect on the audience's support of Cosita Rica.

At the end of the month, however, a gossip column published a note that began a whole new wave of speculations regarding the future of protagonist Paula C. Using the pseudonym “El Sepulturero,” a columnist wrote that Padrón was so upset with Colmenares that he was going to introduce in the telenovela a serial killer, played by a Mexican actor, who would murder several characters, including the protagonist (Sepulturero, 2004a). The supposed addition of the “Mexican psychopath” was repeated by at least two media outlets (Castillo, 2004a; Sepulturero, 2004b), even though Padrón flatly denied it.

The writer knew this unfounded rumor could be damaging to his telenovela. He was right. To audience members, the “Mexican psychopath” was the opposite of the realism they enjoyed and expected in Cosita Rica. On the Internet, message boards buzzed with anger (see Cosita Rica, n.d.):

LET'S UNITE AND REJECT WHAT'S GOING TO HAPPEN IN COSITA RICA!

May 24, 2004

According to the press and to a reliable source, Paula C and Diego will be out of Cosita Rica soon. A serial killer will appear and kill a bunch of characters, including them. Let's say NO to this destruction of our beloved telenovela! I hope that Padrón reads these lines one day and realizes that this is the worst thing he could do!!

–Dragoons

LET'S SAVE COSITA RICA!

May 27, 2004

Padrón wants to damage the telenovela . . . Nooooo . . . The press says that César Evora and another Mexican actor are going to be part of Cosita Rica as a serial killer. How ridiculous!! All Cosita Rica Fans must unite and not allow this to happen! We want the telenovela to continue reflecting the country's situation!!

In this way the stormy month ended with Diego and Paula C. recovering their protagonist status, Cosita Rica regaining first place, but with diminishing ratings, the press being obsessed with the entrance of a serial killer, and Padrón feeling the first signs of fatigue and facing the last months of his very long telenovela.

June–July 2004: Turbulence

In contrast with the situation in May, when Cosita Rica's ratings were not altered by the electric storm generated by its unhappy protagonist, in June the telenovela encountered turbulence that turned on the warning indicators in the cockpit.

The month did not begin well. Cosita Rica lost the ratings in the first two days. The protagonists had been together for a week, and their storyline had lost its dramatic tension. Meanwhile the writer of its main competitor, Estrambótica Anastasia, had included a murder/“who'd done it?” plot that attracted viewers. The audience had become impatient with Cosita Rica, wanting to be constantly surprised by the telenovela. Acknowledging that the main love story's tension was based mostly on keeping the protagonists apart, Padrón generated a new obstacle for their love: Diego is kidnapped by a Colombian guerilla fighter. The audience gave this plot twist a cold reception, even though it evoked similar events that had shaken Venezuelans in the last decade. Furthermore, because Diego's kidnapping coincided with another storyline in which Patria Mía, a favorite character, gets involved with a drug trafficker, the audience felt that Cosita Rica had lost its luminous qualities. Certainly the balance between reality, melodrama, and humor had been altered, and both the ratings and the audience's comments showed the public's displeasure: “They forgot the central idea. Now we have to swallow this modern guerrilla. It's ridiculous. Every time they show kidnapped Diego, I stand up and do something else. It's boring and totally uninteresting” (MONICA, 46). Here is a post on the message board for the show again (Cosita Rica, n.d.):

PLEASSSSEEEE

June 21, 2004

Don't you think that since Fabiola Colmenares' temper tantrum the telenovela has changed? It's now such trash. The protagonist kidnapped, Patria Mía with that junkie. Please don't transform the telenovela into something boring and predictable!

–Elsa

Cosita Rica lost on June 18 and barely won the next day. Padrón declared a state of emergency and called a meeting with his writing team.

I think that Cosita Rica is suffering from erosion at the same time that its competition has become more interesting. To be honest, I don't think people liked the guerrilla plot. I've heard too many comments of people saying that the telenovela is now too serious and kind of heavy. The emergency indicators are definitely on. (Leonardo Padrón: June 21, 2004)

Decisions were made: add more humor to the script, elevate the volume of the characters and storylines that the audience loved (like the love story between Cacique and Verónica), write a three-month time ellipsis (a jump in time) that would solve/dissolve the plots that were not working, and use the telenovela itself to dispel the annoying rumor about the “Mexican psychopath.”14

In the last week of June, the government-controlled network Venezolana de Televisión (VTV) premiered Amores de barrio adentro at 9 p.m. A blatantly pro-Chávez dramatic serial, it changed nothing in the prime-time ratings war because the Venezuelan audience all but ignored it, which suggested that, regardless of their political stance, Venezuelans were not interested in telenovelas that resembled political pamphlets.

Meanwhile, on most days, Cosita Rica and Estrambótica Anastasia were neck and neck in their quest to win ratings. When July arrived, Padrón made a move that returned his telenovela to the first place. Fictional character Olegario Pérez, like Chávez, the real-life character he evoked, now faced a recall referendum relative to his administration of cosmetics corporation Emporio Luján, a metaphor for Venezuela. The audience received this development, plus a refreshing time ellipsis, with pleasure: “Cosita Rica is now in an active and dynamic path. It's like they've given it some oxygen, and now it's as attractive as when it first started” (ROSALBA, 42). “I thought it was great that the telenovela skipped those three months. It gave it a new life” (REBECA, 20).

The writers, the cast, and the production team were exhausted, though. They wanted the telenovela to end as soon as possible. In an extremely polarized country, shooting scenes close to the date of the Chávez referendum worried everyone who worked in Cosita Rica. However, their wish that the telenovela would end before August 15, when the historic referendum was due to take place, was not granted.

The Minister of Information and Communication and members of the Comando Maisanta (the government organization in charge of Chávez's referendum-related political campaign) met with Víctor Ferreres, president of Venevisión, and ordered that Olegario's on-screen referendum could not take place before Chávez's. The network had no recourse but to comply. In this meeting the government made clear that they were following Cosita Rica's stories closely and warned Venevisión about using the telenovela for propaganda purposes. Feeling threatened, the network responded by implementing a self-censorship system. Scripts were carefully read by the network's legal department. Dialogues were modified and some scenes were re-taped, which added yet another layer of complexity to the last month of production.

Even with this annoying self-censorship in place, Padrón knew that Cosita Rica's parallel path with reality could not be altered. July ended with Cosita Rica in first place and increasing its advantage over its competitor day by day. On the 27th, Venevisión announced Cosita Rica's etapa final (final stage) and aired the first promotional broadcast for the telenovela that would substitute it in the 9 p.m. slot.

Venezuelans looked forward to August, when their country's destiny and the fate of the characters that had entertained them for almost a year would be decided.

August 2004: Cosita Rica's Landing

The presidential recall referendum and its consequences marked the month of August. Two weeks before Chávez's referendum, Zeta, a political magazine with a clear oppositional stance, veered from a 30-year-old policy of not showing artists or entertainers on its cover and displayed a picture of Olegario with the headline “‘Olegario’ tá cagao” – “‘Olegario’ Is Shitting His Pants” – which clearly referred to Chávez.

The parallels between the telenovela and the national political arena were unmistakeable. Venezuelans spent most of August 15 in long lines, waiting to vote for or against their president. Actor Carlos Cruz, who played Olegario in the telenovela, also stood in line for many hours to vote. Some passersby from the opposition acted toward him as if he were Chávez: “We're going to revoke you!” “This is your last day in the presidency!” (Carlos Cruz: August 27, 2004). Both political sides were sure they would obtain victory. In the wee hours of the morning of August 16 the CNE announced the president's victory. The opposition cried fraud, while the Organization of American States (OAS) and the Carter Center certified the result. Venezuela was now divided not only between chavistas (pro-Chávez) and antichavistas (anti-Chávez), but also between satisfied and frustrated Venezuelans.

In Cosita Rica it was finally time to prepare the aircraft for landing: resolve plots and decide each character's fate. The line between reality and fiction was further blurred. The entertainment press mentioned the telenovela on a daily basis, and even the political press speculated about the fate of both Chávez and Olegario, while the audience had come back in mass to watch Cosita Rica's last month: “I like everything that's happening in Cosita Rica. I'm enjoying it so very much. Sometimes I want it to end to see what will happen with certain characters. But at other times I don't want it to ever end” (ANDREA, 35).

On August 19, after more than two days of almost non-stop work from the writers, Padrón emailed Cosita Rica's final episode. It consisted of 85 pages and 79 scenes, which ended the telenovela that had put Venevisión back in first place. Cosita Rica landed on August 30, exactly 11 months after it had taken off. Olegario, like Chávez, wins his referendum, and his opponents, like those of Chávez, cry fraud. Paula C. and Diego lived happily ever after. So did Cacique and Verónica, while María Suspiro fulfilled her girlhood dream of becoming Miss Venezuela.

Olegario's ending gave Padrón some unpleasant experiences. He received many anonymous text and phone messages calling him “immoral” and suggesting that he had been co-opted by the Chávez government. Throughout Cosita Rica's 11 months the president's opponents had applauded the parallelisms between Olegario and Chávez. However, they were upset when Olegario won his referendum, because they felt that, just as Olegario was a satire of Chávez (and they liked that), now he was legitimizing the president (and they disliked that). These antichavistas felt that Padrón, Cosita Rica, and Venevisión were deserters in Venezuela's political battle.

The audience enjoyed the final episode, although, for those who opposed the president, “it brought back bad memories from Chávez's referendum” (DANI, 27). Sixteen months after the final episode aired I was still receiving emails from my study participants mentioning Cosita Rica as an unforgettable telenovela that had marked them. After its long journey, Cosita Rica had finally landed. The pilot and crew could finally say thank you and rest:

I truly believe that Cosita Rica will be a memorable chapter in our lives. We achieved a resonance within the audience that surprised us all. Each character became part of Venezuelans' affective imaginary. You, actors, managed to enter the viewers' retinas and furnish their smiles. You became topic and dessert every evening. I want to thank you for giving a piece of your soul to your work. I also want to apologize for the grey scenes, the lukewarm dialogues or the incoherent situations that I may have written. In a journey as long as this one, it was impossible that none of us lose our way, at some point. The important thing is that we've arrived to the end, unbeaten in our quest to make a more dignified television and accompany our country at a historical time of strife. We were the fiction that gave the public laughter, love and reflection. Today I turn off my computer, exhausted and happy, worn out and sad, thankful and taller, older and more human, thanks to you and to this story. Our story. [. . .]

Thank you. As I embrace you I say out loud: thank you.

And my heart stands up and applauds you forever. (Padrón, n.d.)

Conclusion

Those who place their words in the guts of a telenovela know it well: Love without ratings doesn't last.

Barrera Tyszka (2002, p. 65)

The life expectancy of a telenovela is determined by its ratings. “Love without ratings doesn't last” is the tenet of an industry that is often heartless and stubborn in its quest for success. The latter is strictly defined in terms of ratings and shares, which are the currency of the television industry. The quality of a show is never nearly as important as the numbers that measure the audience's choices. From the entertainment press to hardcore telenovela fans, ratings and shares impregnate every aspect related to a telenovela's production and reception.

These numbers also determine the survival of writers in the industry. It is not desirable to have a losing record. And, even though all writers have failures in their trajectory, it is necessary for their permanence in television that these failures are scarce and isolated occurrences. Studying Padrón as he wrote Cosita Rica allowed me to observe how he struggled every day with the tension between the commercial requirements of the genre and his own creative and stylistic needs as an author. I witnessed his battle to couple rating and quality in a commercial product that ends up not being his. On occasions, I saw how he succumbed to the strictly commercial parameters of an industry that can be like a sausage factory. I also witnessed how he overcame these factors and showed the best of his creative talent, as his telenovela encouraged the audience to reflect on the country's polarization and on the nature of political leadership.

Studying Cosita Rica's production process also helped me understand the actors' craft/art in an industry that often does not care for real talent. In Venezuela there is an understanding of celebrity that assumes that Venezuelan actors have the lifestyle of the most glamorous of their Hollywood counterparts. In reality, the large majority of actors belong to the middle class. Most of them are not on the networks' payrolls, but are only hired by the telenovela. Hence their jobs are far from being stable sources of income. Furthermore, in a country where the theater and the film are not nearly as developed as television, telenovelas are the actors' main source of living. The actors' survival, like that of telenovela writers, also depends on the success of the melodrama they are working in. And, sometimes, as in the case of Colmenares and the creator. Padrón, the actor's professional achievement (via the character personified) is at odds with the success of the telenovela and of the writer.

Observing every stage and locus of Cosita Rica's production process, I was struck by the fascinating paradoxes of these shows, which are, simultaneously, consumed and disdained in massive amounts. In telenovelas writers, actors, directors, and producers are determined to be artists striving for perfection in a highly commercial genre, riddled with imperfections arising from the industrial pace of production. In the case of Cosita Rica, this paradox was further complicated with the telenovela's political content and context.

Examining Cosita Rica allowed me to observe the endless search for an answer to the question that dominates and determines the telenovela genre: What does the audience want? Day after day, all those involved in the writing, production, and decision processes try to answer this question and present their bets regarding the right answer. Day after day, they read in ratings and shares how right or wrong they were and whether their wager was a winning or losing bet. This is a life or death gamble for each telenovela and for the professional continuity of its makers. This industrial process is the key to grasping the articulations between media, culture, and society. For Venezuelans, Cosita Rica was entertainment, reflection, and catharsis at a difficult historical juncture. As I witnessed Cosita Rica's flight, I saw first hand the dialogue between television and country, and how creativity was nurtured or restricted by the reality of Venezuela's political moment.

Epilogue

In March 2005, seven months after Cosita Rica ended, the Ley de Responsabilidad Social en Radio y Televisión (Law on Social Responsibility in Radio and Television) went into effect. This law, denounced by Human Rights Watch as coercive and stifling of freedom of expression (Human Rights Watch, 2003), imposes severe penalties on media outlets that do not comply with its content regulations. It includes strict rules regarding telenovelas' language and storylines.

In May 2007, alleging that RCTV was a “terrorist” media outlet, President Chávez did not renew the network's 50-year-old airwave concession. Hence RCTV ceased to exist as a commercial network, while TVES (Televisora Venezolana Social), a government station, occupied RCTV's frequency in the spectrum. Since then, Venevisión, the country's only surviving telenovela-producing network, is under severe self-censorship.

Today it is impossible to produce and broadcast in Venezuela a telenovela like Cosita Rica.

NOTES

1 Briefly, Hall's (1980) “encoding/decoding” model accounted for media producers, texts, and consumers. Johnson described his model as a “circuit” and included production, texts, readings and lived cultures. Du Gay, Hall, MacKay, and Negus (1997) and D'Acci (1994) subsequently included media production, representation, identity, consumption, and regulation in their models for a “circuit of culture.”

2 “In 1999 there were 62 hours and 27 minutes, in 2000, almost 108 hours, in 2001, 116 hours and 58 minutes. In 2002 the figure dropped to 73 hours, but in 2003 there were 165 hours and 35 minutes. Up until July 24, 2004, there were 87.23 hours [of presidential cadenas]” (Marcano & Barrera Tyszka, 2004, p. 278; my translation).

3 A note about typographical conventions: throughout this chapter, quotations from production participants (writers, actors, producers, and technical crew) will be identified under “participant: interview date.” Audience members' words will be recorded under “PSEUDONYM, age.” Quotations from Internet message board and chatrooms will appear under the pseudonym “nick” for each participant.

4 At the time, Brazilian telenovelas had a budget of $100,000–120,000 per episode. In Mexico each episode cost $60,000–80,000. Venezuelan budgets were $15,000–30,000 per episode (Mato, 1999, p. 234).

5 For an actor, working in a telenovela is like being in a year-long acting “bootcamp.” Unlike in film or theater, in a telenovela nobody knows ahead of time all the twists and turns of the plot (not to mention how these unknown factors will affect each character). Furthermore, because telenovelas are broadcast on a daily basis and are not governed by seasons (like US TV series), once production starts, there is little time for actors to plan and strategize. Personifying a telenovela character is like knitting a huge sweater in which the writer holds one knitting needle and the actor holds the other one.

6 Because telenovelas occupy prime-time slots, promotions of the upcoming episode are aired throughout the day.

7 The number of news stories focusing on Cosita Rica more than tripled those dedicated to La invasora.

8 There is no set number of episodes for a telenovela. However, 120 episodes is the standard used in network contracts with writers and actors.

9 The Avila is a mountain that defines life in Caracas.

10 In addition to the main love story, most telenovelas now offer a love story between younger characters. The inclusion of the so-called historia de amor juvenil started as an attempt to lure younger audiences to the genre (Espada, 2004). Today these love stories of younger lovers are a staple of the genre.

11 According to UNICEF, the number of niños de la calle in Venezuela had increased from 2,500 in 1992 to more than 8,000 in 2003, the year Cosita Rica was broadcast (De Venanzi & Hobaica, 2003).

12 I use here the Venezuelan convention of referring to the character by his/her first name.

13 The episode in which Cacique discovered the twins' existence won 15.4 to 6.1 ratings points. On the night when Paula C.'s wedding was interrupted, Cosita Rica won 11.6 to 7.0.

14 In three different episodes, when a character mentioned her/his concern about the existence of the Mexican psychopath, another character replied with undeniable scorn: “There's no Mexican psychopath! Don't believe everything you read in the press!” After that, the press stopped mentioning the “psicópata mexicano.”

REFERENCES

Acosta-Alzuru, C. (2007). Venezuela es una telenovela. Caracas, Venezuela: Alfa.

Acosta-Alzuru, C. (2011). Venezuela's telenovela: Polarization and political discourse in Cosita Rica. In D. Smilde & D. Hellinger (Eds.), Venezuela's Bolivarian Democracy: Participation, Politics, and Culture under Chávez. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Barrera Tyszka, A. (2002, September–December). Desde las tripas de un culebrón. Revista Bigott, 62, 62–65.

Benzaquen, H. J. (2004, March 12). Municipio Chacao condecoró a Elinor Montes. El Nacional, p. A/6.

Blanco, C. (2002). Revolución y desilusión: La Venezuela de Hugo Chávez. Madrid, Spain: Catarata.

Cabrujas, J. I. (2002). Y Latinoamérica inventó la telenovela. Caracas, Venezuela: Alfadil.

Castillo, M. (2004a, May 25). Olla de grillos: Bodas y corazones. El Mundo, p. 19.

Castillo, M. (2004b, May 11). Olla de grillos: La renuncia de Paula C. El Mundo, p. 20.

Castillo, M. (2004c, May 18). Olla de grillos: Tolerancia y especulación. El Mundo, p. 19.

Cosita Rica. (n.d.). Network54. Retrieved March 25, 2012, from http://www.network54.com/Forum/223657/

D'Acci, J. (1994). Defining women: Television and the case of Cagney and Lacey. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

D'Acci, J. (2004). Cultural studies, television studies, and the crisis in the humanities. In L. Spigel & J. Olsson (Eds.), Television after TV (pp. 418–445). Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

De Venanzi, A., & Hobaica, G. (2003). Niños de la calle. ¿Una clase social? Trabajo y sociedad, 5(6), pp. 24–42.

du Gay, P. (1997). Introduction. In P. du Gay (Ed.), Production of culture/Cultures of production (pp. 1–10). London, UK: Sage.

du Gay, P., Hall, S., MacKay, H., & Negus, K. (1997). Doing cultural studies: The story of the Sony Walkman. London, UK: Sage.

Espada, C. (2004). La telenovela en Venezuela. Caracas, Venezuela: Fundación Bigott.

Forero, J. (2003, February 17). Love! Power! Squalor! TV Dramas tune in politics. New York Times, p. A–8.

Gitlin, T. (1983). Inside prime time. London, UK: Routledge.

Grossberg, L. (1997). Bringing it all back home: Essays on cultural studies. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Grossberg, L., Nelson, C., & Treichler, P. (1992). Cultural studies. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hall, S. (1980). Encoding/decoding. In S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe, & P. Willis (Eds.), Culture, media, language: Working papers in cultural studies (pp. 128–138). London, UK: Hutchinson.

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In S. Hall (Ed.), Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 13–74). London, UK: Sage.

Hawkins, E. T. (2003, August). Media and the crisis of democracy in Venezuela. Paper presented at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Kansas City, Missouri.

Human Rights Watch. (2003). Retrieved February 3, 2004, from www.hrw.org/press/2003/06/venezuela062303-ltr.htm

Hyppolite, N. (2000, June). Por estas calles [Down these streets]. Paper presented at the International Communication Association, Acapulco, Mexico.

Johnson, R. (1986/87). What is cultural studies anyway? Social Text, 16, 38–80.

Kellner, D. (1995). Cultural studies, multiculturalism, and media culture. In G. Dines & J. Humez (Eds.), Gender, race and class in media (pp. 5–17). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

La Pastina, A. (2004). Selling political integrity: Telenovelas, intertextuality and local elections in Brazil. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 48, 302–325.

Levine, E. (2001). Toward a paradigm for media production research: Behind the scenes at General Hospital. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 18(1), 66–82.

MacKay, H. (1997). Introduction. In H. MacKay (Ed.), Consumption and everyday life (pp. 1–12). London, UK: Sage.

Marcano, C., & Barrera Tyszka, A. (2004). Hugo Chávez sin uniforme: Una historia personal. Caracas, Venezuela: Editorial Debate.

Márquez, P. (1999). The street is my home: Youth and violence in Caracas. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Martín-Barbero, J. (1993). Communication, culture and hegemony: From the media to mediations. London, UK: Sage.

Martín-Barbero, J., & Rey, G. (1999). Los ejercicios del ver: Hegemonía audiovisual y ficción televisiva. Barcelona, Spain: Gedisa.

Mato, D. (1999). Telenovelas: Trasnacionalización de la industria y transformaciones del género. In N. García Canclini & C. J. Moneta (Eds.), Industrias culturales e integratión latinoamericana (pp. 229–257). Buenos Aires, Argentina: EUDEBA.

Mato, D. (2005). The transnationalization of the telenovela industry, territorial references, and the production of markets and representations of transnational identities. Television and New Media, 6(4), 423–444.

Mayer, V., Banks, M. J., & Caldwell, J. T. (2009). Introduction: Production studies: Roots and routes. In V. Mayer, M. J. Banks, & J. T. Caldwell (Eds.), Production studies: Cultural studies of media industries (pp. 1–12). New York, NY: Routledge.

McAnany, E. G., & La Pastina, A. (1994). Telenovela audiences: A review and methodological critique of Latin America research. Communication Research, 21(6), 828–849.

Negus, K. (1997). The production of culture. In P. du Gay (Ed.), Production of culture/Cultures of production (pp. 67–118). London, UK: Sage.

Padrón, L. (2002, September–December). La telenovela: ¿género literario del Siglo XXI? Revista Bigott, 62, 44–54.

Padrón, L. (n.d.). Notes to the cast at the end of the final episode's script. Unpublished manuscript.

Porto, M. (1998). Telenovelas and politics in the 1994 Brazilian presidential election. The Communication Review, 2(4), 433–459.

Porto, M. (2005). Political controversies in Brazilian TV fiction: Viewers' interpretations of the telenovela Terra nostra. Global Media Journal, 6(4), 342–359.

Quiroz, M. T. (1993). La telenovela en el Perú. In A. Fadul (Ed.), Serial fiction in TV: The Latin American telenovelas (pp. 33–46). São Paulo, Brazil: Universidad de São Paulo.

Sepulturero, E. (2004a, May 22). A la fosa y sin mortaja: ¿Matan a Paula C? Ultimas Noticias, p. 56.

Sepulturero, E. (2004b, May 24). A la fosa y sin mortaja: La duda de Leo. Ultimas Noticias, p. 54.

Sepulturero, E. (2004c, May 15). A la fosa y sin mortaja: Padrón despechado. Ultimas Noticias, p. 60.

Silva, K. (2004, May 13). Padrón desmiente renuncia de Fabiola Colmenares. El National, p. B10.

Straubhaar, J. D. (1988). The reflection of the Brazilian political liberalization in the telenovela, 1974–1984. Studies in Latin American Popular Culture, 7, 59–76.

Tremamunno, M. (2002). Presentación. In M. Tremamunno (Ed.), Chávez y los medios de comunicación social (pp. 7–11). Caracas, Venezuela: Alfadil.

Villegas Poljak, V. (2002). Medios vs. Chávez: La lucha continúa. In M. Tremamunno (Ed.), Chávez y los medios de comunicación social (pp. 47–60). Caracas, Venezuela: Alfadil.

Ytreberg, E. (2000). Notes on text production as a field of inquiry in media studies. Nordicom Review, 21(2), 53–62.

FURTHER READING

Born, G. (2004). Uncertain vision: Birt, Dyke and the reinvention of the BBC. London, UK: Secker & Warburg.

Caldwell, J. T. (2008). Production culture: Industrial reflexivity and critical practice in film and television. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Jacobs, R. N. (1996). Producing the news, producing the crisis: Narrativity, television, and news work. Media, Culture and Society, 18, pp. 373–397.

Kellner, D. (1997). Overcoming the divide: Cultural studies and political economy. In M. Ferguson & P. Golding (Eds.), Cultural studies in question (pp. 102–120). London, UK: Sage.

Lotz, A. D. (2004). Textual (im)possibilities in the US post-network era: Negotiating production and promotion processes on Lifetime's Any Day Now. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 21(1), 22–43.

Rivero, Y. M. (2002). Erasing Blackness: The media construction of “race” in Mi familia, the first Puerto Rican situation comedy with a Black family. Media, Culture and Society, 4(4), 459–480.