FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

Abstract: The securities issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury include bills, notes, and bonds. The U.S. Treasury market is a closely watched market by market participants throughout the world because it plays a prominent role in the global financial market for two reasons. First, because the securities are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, they are viewed as default-free securities and therefore the yields on these securities are viewed as benchmark risk-free interest rates. Second, because of the large size of the market and the large size of each individual issue, the Treasury market is the most active and liquid sector of the global financial market.

Keywords: Treasury securities, Treasuries, or government bonds, fixed-principal securities, Treasury bills, Treasury coupon securities, Treasury notes, Treasury bonds, cash management bills, Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), real rate, inflation-adjusted principal, reopening of an issue, noncompetitive bid, competitive bid, stop-out yield, high yield, bid-to-cover ratio, single-price auction, Dutch auction, on-the-run issue, current issue, off-the-run issue, when-issued market, interdealer brokers, bank discount basis, bond-equivalent yield, CD equivalent yield, money market equivalent yield, coupon stripping, corpus, principal strips, reconstitution

The securities issued by the U.S. Department of the Treasury (U.S. Treasury hereafter) are called Treasury securities, Treasuries, or U.S. government bonds. Because they are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, market participants throughout the world view them as having no credit risk. Hence, the interest rates on Treasury securities are the benchmark default-free interest rates.

Treasury securities are classified as nonmarketable and marketable securities. The former securities include savings bonds that are sold to individuals and state and local government series (SLGS) securities that are sold to state and local government issuers of tax-exempt securities. Market securities can be bought, sold, or transferred after they are issued. The Public Debt Act of 1942 grants the U.S. Treasury considerable discretion in deciding on the terms for a marketable security. An issue may be sold on an interest-bearing or discount basis and may be sold on a competitive or other basis, at whatever prices the Secretary of the Treasury may establish.

In this chapter, the different types of marketable Treasury securities are explained as well their primary and secondary markets. The relationship between the interest rate on Treasury securities and maturity is referred to as the Treasury yield curve. This relationship and how it is used in valuing fixed income securities is described in Chapters 36, 37, and 38 of Volume III. There are derivative instruments in which Treasury securities are the underlying. These contracts are described in Chapter 39 of Volume I.

There are two types of marketable Treasury securities issued: fixed-principal securities and inflation-indexed securities.

The U.S. Treasury issues two types of fixed-principal securities: discount securities and coupon securities. Discount securities are called Treasury bills; coupon securities are called Treasury notes and Treasury bonds.

Treasury bills are issued at a discount to par value, have no coupon rate, and mature at face value. Generally, Treasury bills can be issued with a maturity of up to two years. The U.S. Treasury typically issues only certain maturities. As of year-end 2007, the practice of the U.S. Treasury is to issue Treasury bills with maturities of 4 weeks, 13 weeks, 26 weeks, and 6 months. At one time, the U.S. Treasury issued a 1-year Treasury bill. In addition, the Treasury Department issues cash management bills that can have a maturity from 1 to 7 days, depending on its borrowing needs.

As discount securities, Treasury bills do not pay coupon interest. Instead, Treasury bills are issued at a discount from their face value; the return to the investor is the difference between the face value and the purchase price.

The U.S. Treasury issues securities with initial maturities of two years or more as coupon securities. Coupon securities are issued at approximately par and, in the case of fixed-principal securities, mature at par value. They are not callable. Treasury notes are coupon securities issued with original maturities of more than two years but no more than 10 years. As of year-end 2007, the U.S. Treasury issues a 2-year note, a 5-year note, and a 10-year. At one time the U.S. Treasury issued a 3-year notes and 7-year notes. Treasuries with original maturities greater than 10 years are called Treasury bonds. As of year end 2007, the U.S. Treasury issues a 30-year bond. The U.S. Treasury had stopped issuing 30-year bonds in October 2001 but resumed issuing them in February 2006. At one time the U.S. Treasury issued 20-year bonds but ceased doing so in January 1986.

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities

The U.S. Treasury issues coupon securities that provide inflation protection. They do so by having the principal increase or decrease based on the rate of inflation such that when the security matures, the investor receives the greater of the principal adjusted for inflation or the original principal. These Treasury securities, first introduced in January 1997, are popularly referred to as Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS). As of year-end 2007, the U.S. Treasury issues a 5-year TIPS, a 10-year TIPS, and a 20-year TIPS.

TIPS work as follows. The coupon rate on an issue is set at a fixed rate, the rate being determined via the auction process described later in this chapter. The coupon rate is referred to as the real rate because it is the rate that the investor ultimately earns above the inflation rate. The inflation index used for measuring the inflation rate is the nonseasonally-adjusted U.S. City Average All Items Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U).

The adjustment for inflation is as follows: The principal that the U.S. Treasury will base both the dollar amount of the coupon payment and the maturity value on is adjusted semiannually. This is called the inflation-adjusted principal. For example, suppose that the coupon rate for a TIPS is 3.5% and the annual inflation rate is 3%. Suppose further that an investor purchases on January 1 $100,000 par value (principal) of this issue. The semiannual inflation rate is 1.5% (3% divided by 2). The inflation-adjusted principal at the end of the first six-month period is found by multiplying the original par value by one plus the semiannual inflation rate. In our example, the inflation-adjusted principal at the end of the first six-month period is $101,500. It is this inflation-adjusted principal that is the basis for computing the coupon interest for the first six-month period. The coupon payment is then 1.75% (one-half the real rate of 3.5%) multiplied by the inflation-adjusted principal at the coupon payment date ($101,500). The coupon payment is therefore $1,776.25.

Let's look at the next six months. The inflation-adjusted principal at the beginning of the period is $101,500. Suppose that the semiannual inflation rate for the second six-month period is l%. Then the inflation-adjusted principal at the end of the second six-month period is the inflation-adjusted principal at the beginning of the six-month period ($101,500) increased by the semiannual inflation rate (1%). The adjustment to the principal is $1,015 (1% times $101,500). So, the inflation-adjusted principal at the end of the second six-month period (December 31 in our example) is $102,515 ($101,500 + $1,015). The coupon interest that will be paid to the investor at the second coupon payment date is found by multiplying the inflation-adjusted principal on the coupon payment date ($102,515) by one-half the real rate (that is, one-half of 3.5%). That is, the coupon payment will be $1,794.01.

As can be seen, part of the adjustment for inflation comes from the coupon payment since it is based on the inflation-adjusted principal. However, the U.S. government has decided to tax the adjustment each year. This feature reduces the attractiveness of TIPS as investments in accounts of tax-paying entities.

Because of the possibility of disinflation (that is, price declines), the inflation-adjusted principal at maturity may turn out to be less than the original par value. However, the Treasury has structured TIPS so that they are redeemed at the greater of the inflation-adjusted principal and the original par value.

An inflation-adjusted principal must be calculated for a settlement date if an issue is sold prior to maturity. The inflation-adjusted principal is defined in terms of an index ratio, which is the ratio of the reference CPI for the settlement date to the reference CPI for the issue date. The reference CPI is calculated with a three-month lag. For example, the reference CPI for May 1 is the CPI-U reported in February. The U.S. Department of the Treasury publishes and makes available on its web site a daily index ratio for an issue.

Treasury securities are sold in the primary market through an auction process. Each auction is announced several days in advance by means of a Treasury Department press release or press conference. The announcement provides details of the offering, including the offering amount and the term and type of security being offered, and describes some of the auction rules and procedures. Treasury auctions are open to all entities.

The U.S. Treasury makes the determination of the procedure for auctioning new Treasury securities, when to auction them, and what maturities to issue. There are periodic changes in the auction cycles and the maturity of the issues auctioned.

While the Treasury regularly offers new securities at auction, it often offers additional amounts of outstanding securities. This is referred to as a reopening of an issue. The Treasury has established a regular schedule of reopen-ings for certain maturities. To maintain the sizes of its new issues and help manage the maturity of its debt, the Treasury launched a debt buyback program. Under the program, the Treasury redeems outstanding unmatured Treasury securities by purchasing them in the secondary market through reverse auctions.

The auction for Treasury securities is conducted on a competitive bid basis. There are two types of bids that may be submitted by a bidder: noncompetitive bids and competitive bids. A noncompetitive bid is submitted by an entity that is willing to purchase the auctioned security at the yield that is determined by the auction process. When a noncompetitive bid is submitted, the bidder specifies only the quantity sought. The quantity in a noncompetitive bid may not exceed a specified amount. A competitive bid specifies both the quantity sought and the yield at which the bidder is willing to purchase the auctioned security.

The auction results are determined by first deducting the total noncompetitive tenders and nonpublic purchases (such as purchases by the Federal Reserve) from the total securities being auctioned. The remainder is the amount to be awarded to the competitive bidders. The competitive bids are then arranged from the lowest yield bid to the highest yield bid submitted. (This is equivalent to arranging the bids from the highest price to the lowest price that bidders are willing to pay) Starting from the lowest yield bid, all competitive bids are accepted until the amount to be distributed to the competitive bidders is completely allocated. The highest yield accepted by the Treasury is referred to as the stop-out yield (or high yield). Bidders whose bid is higher than the stop-out yield are not distributed any of the new issue (that is, they are unsuccessful bidders). Bidders whose bid was the stop-out yield (that is, the highest yield accepted by the Treasury) are awarded a proportionate amount for which they bid. For example, suppose that $4 billion was tendered for at the stop-out yield, but only $1 billion remains to be allocated after allocating to all bidders who bid lower than the stop-out yield. Then each bidder who bid the stop-out yield will receive 25% of the amount for which they tendered. So, if an entity tendered for $12 million, then that entity would be awarded only $3 million.

The results announced by the U.S Treasury include the stop-out yield, the associated price, and the proportion of securities awarded to those investors who bid exactly the stop-out yield. Also announced is the quantity of non-competitive tenders, the median-yield bid, and the ratio of the total amount bid for by the public to the amount awarded to the public (called the bid-to-cover ratio). For notes and bonds, the announcement includes the coupon rate of the new security. The coupon rate is set to be that rate (in increments of one-eighth of 1%) that produces the price closest to, but not above, par when evaluated at the yield awarded to successful bidders.

Now we know how the winning bidders are determined and the amount that successful bidders will be allotted, the next question is the yield at which they are awarded the auctioned security. All U.S. Treasury auctions are single-price auctions. In a single-price auction, all bidders are awarded securities at the highest yield of accepted competitive tenders (that is, the high yield). This type of auction is called a Dutch auction.

The secondary market for Treasury securities is an over-the-counter (OTC) market where a group of U.S. government securities dealers offers continuous bid and ask prices on outstanding Treasuries. There is virtual 24-hour trading of Treasury securities. The three primary trading locations are New York, London, and Tokyo. The normal settlement period for Treasury securities is the business day after the transaction day ("next day" settlement).

The most recently auctioned issue is referred to as the on-the-run issue or the current issue. A security that is replaced by the on-the-run issue is called an off-the-run issue. At a given point in time there may be more than one off-the-run issue with approximately the same remaining maturity as the on-the-run issue. Treasury securities are traded prior to the time they are issued by the Treasury. This component of the Treasury secondary market is called the when-issued market, or WI market. When-issued trading for both bills and coupon securities extends from the day the auction is announced until the issue day.

Government dealers trade with the investing public and with other dealer firms. When they trade with each other, it is through intermediaries known as interdealer brokers. Dealers leave firm bids and offers with interdealer brokers who display the highest bid and lowest offer in a computer network tied to each trading desk and displayed on a monitor. Dealers use interdealer brokers because of the speed and efficiency with which trades can be accomplished.

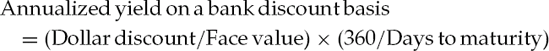

Bids and offers on Treasury bills are quoted in a different way than Treasury coupon securities. Unlike Treasury notes and bonds that pay interest semiannually, Treasury bills prices are quoted on a bank discount basis using the following formula:

where dollar discount is the difference between the face value and the price.

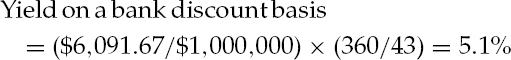

As an example, consider a Treasury bill with 43 days to maturity, a face value of $1 million, and selling for $993,908.33. The dollar discount is $6,091.67. The annualized yield on a bank discount basis is then

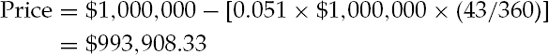

The price of a Treasury bill can be determined from the yield on a bank discount basis by using the following formula:

| Price = Face value — [Yield on a bank discount basis |

| × Face value × (Days to maturity/360)] |

For example, consider again the 43-day Treasury bill. If the yield on a bank discount basis is 5.1%, then the price is

As a yield measure, the yield on a bank discount basis is flawed for two reasons. First, the measure is based on a face-value investment rather than on the actual dollar amount invested. Second, the yield is annualized according to a 360-day rather than a 365-day year, making it difficult to compare Treasury bill yields with Treasury notes and bonds, which pay interest on a 365-day basis. The use of 360 days for a year is a money market convention. Despite its shortcomings as a measure of return, this is the method that dealers have adopted to quote Treasury bills.

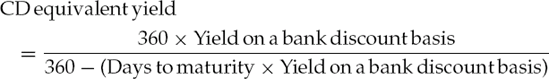

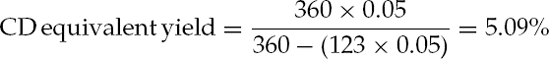

The yield measure employed by market participants to make the quotes on Treasury bills comparable to Treasury notes and bonds is called the bond-equivalent yield. The CO equivalent yield, also called the money market equivalent yield, makes the quoted yield on a Treasury bill more comparable to yield quotations on other money market instruments that pay interest on a 360-day basis. This is achieved by taking into consideration the price of the Treasury bill rather than its face value. The formula for the CD equivalent yield is

As an illustration, consider a 123-day Treasury bill with a face value of $1 million, selling for $982,916.67, and offering a yield on a bank discount basis of 5%. Then

Treasury coupon securities are quoted on a price basis in points. One point is equal to 1% of par. The points are split into units of 32nds, so that a price of 97-14, for example, refers to a price of 97 and 14 32nds, or 97.4375 per 100 of par value. The 32nds are themselves often split by the addition of a plus sign or a number. A plus sign indicates that half a 32nd (or a 64th) is added to the price, and a number indicates how many eighths of 32nds (or 256ths) are added to the price. A price of 97-14+, therefore, refers to a price of 97 plus 14 32nds plus one 64th, or 97.453125, and a price of 97-142 refers to a price of 97 plus 14 32nds plus 2 256ths, or 97.4453125.

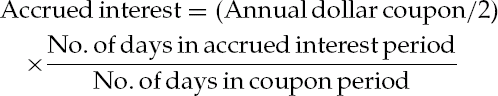

The buyer of a Treasury coupon security must compensate the seller of the bond for accrued interest (that is, the coupon interest earned from the time of the last coupon payment to the settlement date of the bond). In general, when calculating accrued interest for any bond, three pieces of information are needed: (1) the number of days in the accrued interest period, (2) the number of days in the coupon period, and (3) the dollar amount of the coupon payment. The number of days in the accrued interest period is the number of days over which the seller has earned interest before selling the security. For Treasury coupon securities, the convention used is to determine the actual number of days between two dates, referred to as the actual/actual day count convention.

The calculation of the actual number of days in the accrued interest period and the number of days in the coupon period begins with the determination of three key dates: trade date, settlement date, and date of the previous coupon payment. The trade date is the date on which the transaction is executed. The settlement date is the date a transaction is completed. For Treasury securities, settlement is the next business day after the trade date. Interest accrues on a Treasury coupon security from and including the date of the previous coupon payment up to but excluding the settlement date.

Given these values, the accrued interest for Treasury coupon securities is

The U.S. Treasury does not issue zero-coupon notes or bonds. However, because of the demand for zero-coupon instruments with no credit risk, the private sector has created such securities using a process called coupon stripping.

To illustrate the process, suppose that $2 billion of a 10-year fixed-principal Treasury note with a coupon rate of 5% is purchased by a dealer firm to create zero-coupon Treasury securities. The cash flow from this Treasury note is 20 semiannual payments of $50 million each ($2 billion times 0.05 divided by 2) and the repayment of principal (also called the corpus) of $2 billion 10 years from now. As there are 21 different payments to be made by the U.S. Treasury for this note, a security representing a single payment claim on each payment is issued, which is effectively a zero-coupon Treasury security. The amount of the maturity value or a security backed by a particular payment, whether coupon or corpus, depends on the amount of the payment to be made by the U.S. Treasury on the underlying Treasury note. In our example, 20 zero-coupon Treasury securities each have a maturity value of $50 million, and one zero-coupon Treasury security, backed by the corpus, has a maturity value of $2 billion. The maturity dates for the zero-coupon Treasury securities coincide with the corresponding payment dates by the U.S. Treasury.

Zero-coupon Treasury securities are created as part of the U.S. Treasury's Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities (STRIPS) program to facilitate the stripping of designated Treasury securities. Today, all Treasury notes and bonds (fixed-principal and inflation-indexed) are eligible for stripping. The zero-coupon Treasury securities created under the STRIPS program are direct obligations of the U.S. government. Moreover, the securities clear through the Federal Reserve's book-entry system.

On dealer quote sheets and vendor screens, STRIPS, or simply, strips, are identified by whether the cash flow is created from the coupon (denoted ci), principal from a Treasury bond (denoted bp), or principal from a Treasury note (denoted np). Strips created from the coupon are called coupon strips and strips created from the principal are called principal strips.

A disadvantage of a taxable entity's investing in stripped Treasury securities is that accrued interest is taxed each year even though interest is not paid. Thus, these instruments are negative cash flow instruments until the maturity date. They have negative cash flow because tax payments on interest earned but not received in cash must be made. One reason for distinguishing between coupon strips and principal strips is that some foreign buyers have a preference for principal strips. This preference is due to the tax treatment of the interest in their home country. The tax laws of some countries treat the interest from a principal strip as a capital gain, which receives a preferential tax treatment (that is, lower tax rate) compared with ordinary interest income if the stripped security was created from a coupon strip.

A market participant can purchase in the market a package of zero-coupon Treasury securities such that the cash flow of the package of securities replicates the cash flow of a mispriced Treasury coupon security. By doing so, the market participant will realize a yield higher than the yield on the Treasury coupon security. This process is called re-constitution.

The U.S. Treasury issues Treasury bills (a discount security) and Treasury notes and bonds (coupon securities) via a competitive bidding auction process according to a regular auction cycle. Treasury coupon securities include fixed-principal and inflation-protected principal securities. Securities issued by the U.S. Treasury are viewed as free of credit risk and therefore serve as a benchmark for the risk-free interest rates in the market. While the U.S. Treasury does not issue zero-coupon notes and bonds, these instruments are created through the U.S. Treasury's STRIPS program via a coupon stripping process by dealers.

Fabozzi, F. J. (1998). Treasury Securities and Derivatives (John Wiley & Sons, 1998).

Fabozzi, F. J., and Fleming, M. J. (2005). U.S. Treasury and agency securities. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities (pp. 229–250). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fleming, M. J. (1997). The round-the-clock market for U.S. Treasury securities. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, July: 9-32.

Fleming, M. J. (1999). Price formation and liquidity in the U.S. Treasury market: The response to public information. Journal of Finance 54, 5: 1901-1915.

Fleming, M. J. (2002). Are larger Treasury issues more liquid? Evidence from bill reopenings. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 34, 3: 707-735.

Fleming, M. J. (2003). Meauring Treasury market liquidity. Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic Policy Review, September: 83-108.

Fleming, M. J. (2007). Who buys Treasury securities at auction? Current Issues in Economics and Finance 13, 1: 1-17.