MOORAD CHOUDHRY, PhD

Head of Treasury, KBC Financial Products, London

FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

STEVEN V. MANN, PhD

Professor of Finance, Moore School of Business, University of South Carolina

Abstract: A corporation that needs long-term funds can raise those funds in either the bond or equity markets. Alternatively, if a corporation needs short-term funds, it may attempt to acquire funds via bank borrowing. One close substitute to bank borrowing for larger corporations with strong credit ratings is commercial paper. Commercial paper is a short-term promissory note issued in the open market as an obligation of the issuing entity. Commercial paper is sold at a discount and pays face value at maturity. The discount represents interest to the investor in the period to maturity. Although some issues are in registered form, commercial paper is typically issued in bearer form.

Keywords: direct paper, dealer paper, rollover risk, yield on a bank discount basis, asset-backed commercial paper, special purpose corporation, conduit, single seller, multi-seller, liquidity enhancement

The commercial paper market was developed in the United States in the latter days of the nineteenth century and was once the province of larger corporations with superior credit ratings. However, in recent years, many lower-credit-rated corporations have issued commercial paper by obtaining credit enhancements or other collateral to allow them to enter the market as issuers. Issuers of commercial paper are not limited to U.S. corporations; non-U.S. corporations and sovereign issuers also issue commercial paper. Commercial paper was first issued in the United Kingdom in 1986 and was subsequently issued in other European countries.

Although the original purpose of commercial paper was to provide short-term funds for seasonal and working capital needs, it has been issued for other purposes, most prominently for "bridge financing." For example, suppose that a corporation desires long-term funds to build a plant or acquire equipment. Rather than raising long-term funds immediately, the issuer may choose to postpone the offering until more favorable capital market conditions prevail. The funds raised by issuing commercial paper are employed until longer-term securities are issued. Commercial paper is also used as bridge financing to finance corporate takeovers.

In this chapter, we describe the characteristics of commercial paper and its investment characteristics.

The maturity of commercial paper is typically less than 270 days; a typical issue matures in less than 45 days. Naturally, there are reasons for this. First, the Securities and Exchange Act of 1933 requires that securities be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Special provisions in the 1933 act exempt commercial paper from these registration requirements so long as the maturity does not exceed 270 days. To avoid the costs associated with registering issues with the SEC, issuers rarely issue commercial paper with a maturity exceeding 270 days. In Europe, commercial paper maturities range between 2-365 days. To pay off holders of maturing paper, issuers generally "rollover" outstanding issues; that is, they issue new paper to pay off maturing paper.

Another consideration in determining the maturity is whether the paper would be eligible collateral by a bank if it wanted to borrow from the Federal Reserve Bank's discount window. In order to be eligible, the paper's maturity may not exceed 90 days. Because eligible paper trades at a lower cost than paper that is ineligible, issuers prefer to sell paper whose maturity does not exceed 90 days.

The combination of its short maturity and low credit risk make commercial paper an ideal investment vehicle for short-term funds. Most investors in commercial paper are institutional investors. Money market mutual funds are the largest single investor of commercial paper. Pension funds, commercial bank trust departments, state and local governments, and nonfinancial corporations seeking short-term investments comprise most of the balance.

The market for commercial paper is a wholesale market and transactions are typically sizeable. The minimum round-lot transaction is $100,000. Some issuers will sell commercial paper in denominations of $25,000. Commercial paper comprises one of the largest sectors of money market approaching $2 trillion outstanding at the end of 2006 according to the Federal Reserve.

Commercial paper is classified as either direct paper or dealer paper. Direct paper is sold by an issuing firm directly to investors without using a securities dealer as an intermediary. The vast majority of the issuers of direct paper are financial firms. Because financial firms require a continuous source of funds in order to provide loans to customers, they find it cost effective to have a sales force to sell their commercial paper directly to investors. Direct issuers post rates at which they are willing to sell commercial paper with financial information vendors such as Bloomberg, Reuters, and Telerate.

Although commercial paper is a short-term security, it is issued within a longer term program, usually for three to five years for European firms: U.S. commercial paper programs are often open-ended. For example, a company might establish a five-year commercial paper program with a limit of $100 million. Once the program is established, the company can issue commercial paper up to this amount. The program is continuous and new paper can be issued at any time, daily if required.

In the case of dealer placed commercial paper, the issuer uses the services of a securities firm to sell its paper. Commercial paper sold in this manner is referred to as dealer paper. Competitive pressures have forced dramatic reductions in the underwriting fees charged by dealer firms.

Historically, the dealer market has been dominated by large investment banking firms because the Glass-Steagall Act prohibited commercial banks from underwriting commercial paper. In June 1987, however, the Federal Reserve granted subsidiaries of bank holding companies the power to underwrite commercial paper. Commercial banks began immediately making inroads into the dealer market that was once the exclusive province of investment banking firms. This process was further accelerated when the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act was signed into law in November 1999. The reforms enacted in the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act repealed the Glass-Steagall Act that mandated artificial barriers between commercial banks, investment banks, and insurance companies. Now each is free to expand into the others' businesses.

Although commercial paper is one of the largest sectors of the money market, there is relatively little trading in the secondary market. The reason is that most investors in commercial paper follow a "buy-and-hold" strategy. This is to be expected because investors purchase commercial paper that matches their specific maturity requirements. Any secondary market trading is usually concentrated among institutional investors in a few large, highly rated issues. If investors wish to sell their commercial paper, they can usually sell it back to the original seller either dealer or issuer.

All investors in commercial paper are exposed to credit risk. Credit risk is the possibility the investor will not receive the timely payment of interest and principal at maturity. While some institutional investors do their own credit analysis, most investors assess a commercial paper's credit risk using ratings by a nationally recognized statistical rating organizations (NRSROs). Table 27.1 presents the commercial paper ratings from Fitch, Moody's, and Standard & Poor's.

Table 27.1. Ratings of Commercial Paper

Fitch | Moody's | S&P | |

|---|---|---|---|

Superior | F1+/F1 | P1 | A1+/A1 |

Satisfactory | F2 | P2 | A2 |

Adequate | F3 | P3 | A3 |

Speculative | F4 | NP | B, C |

Defaulted | F5 | NP | D |

The risk that the investor faces is that the borrower will be unable to issue new paper at maturity. This risk is referred to as rollover risk. As a safeguard against rollover risk, commercial paper issuers secure backup lines of credit sometimes called "liquidity enhancement." Most commercial issuers maintain 100% backing because the NRSROs that rate commercial paper usually require a bank line of credit as a precondition for a rating. However, some large issues carry less than 100% backing. Backup lines of credit typically contain a "material adverse change" provision that allows the bank to cancel the credit line if the financial condition of the issuing firm deteriorates substantially (see Stojanovic and Vaughan, 1998). Historically, defaults on commercial paper have been relatively rare.

The commercial paper market is divided into tiers according to credit risk ratings. The "top top tier" consists of paper rated A1+/P1/F1+. "Top tier" is paper rated Al/Pl, Fl. Next, "split tier" issues are rated either A1/P2 or A2/P1. The "second tier" issues are rated A2/P2.

The yields offered on commercial paper track those of other money market instruments. Like Treasury bills, commercial paper is a discount instrument. In other words, it is sold at a price less than its maturity value. The difference between the maturity value and the price paid is the interest earned by the investor, although some commercial paper is issued as an interest-bearing instrument.

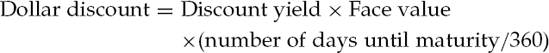

As an example, consider some 30-day commercial paper issued with a yield on a bank discount basis of 5.24%. Assume that the relevant day-count convention is actual/ 360. Given the yield on a bank discount basis, the price is found by first solving for the dollar discount as follows:

The price is then found as follows:

Assuming a face value of $100, the discount is equal to

Therefore,

The yields offered on commercial paper are highly correlated with those of other money market instruments. Moreover, the yields on commercial paper are higher than Treasury bill yields, other things being equal. There are three reasons for this relationship. First, the investor in commercial paper is exposed to credit risk. Second, interest earned from investing in Treasury bills is exempt from state and local income taxes. As a result, commercial paper has to offer a higher yield to offset this tax advantage offered by Treasury bills. Finally, commercial paper is far less liquid than Treasury bills. The liquidity premium demanded is probably small, however, because commercial paper investors typically follow a buy-and-hold strategy and therefore they are less concerned with liquidity.

The yields offered on commercial paper track those of other money market instruments. Generally, CP trades below LIBOR because of a liquidity premium, although lower-tier paper sometimes trades above LIBOR, depending on the appetite for corporate credit at the time.

Asset-backed commercial paper (hereafter, ABCP) is commercial paper issued by either corporations or large financial institutions through a bankruptcy-remote special purpose corporation.

ABCP is usually issued to finance the purchase of receivables and other similar assets, Some examples of assets underlying these securities include trade receivables (that is, business-to-business receivables), credit card receivables, equipment loans, automobile loans, health care receivables, tax liens, consumer loans, and manufacturing-housing loans. According to FitchRatings (Fitch, 1999), historically trade receivables have been securitized most often. The reason being is that trade receivables have maturities approximating that of the commercial paper. Recently, the list of assets has expanded to include rated asset-backed, mortgage-backed, and corporate debt securities as ABCP issuers have attempted to take advantage of arbitrage opportunities in bond markets. There are three types of securities arbitrage programs in existence at the time of this writing: limited purpose investment companies, market value ABC paper programs, and credit arbitrage ABC paper programs. For a discussion of this process, see Dierdorff (1999).

The issuance of ABCP may be desirable for one or more of the following reasons: (1) it offers lower-cost funding compared with traditional bank loan or bond financing; (2) it is a mechanism by which assets such as loans can be removed from the balance sheet; and (3) it increases a borrower's funding options.

According to Moody's (see Adelson, 1993) an investor in ABCP is exposed to three major risks. First, the investor is exposed to credit risk because some portion of the receivables being financed through the issue of ABCP will default, resulting in losses. Obviously, there will always be defaults so the risk faced by investors is that the losses will be in excess of the credit enhancement. Second, liquidity risk which is the risk that collections on the receivables will not occur quickly enough to make principal and interest payments to investors. Finally, there is structural risk that involves the possibility that the ABCP conduit may become embroiled in a bankruptcy proceeding, which disrupts payments on maturing commercial paper.

An ABCP issue starts with one seller or multiple sellers' portfolio of receivables generated by a number of obligors (e.g., credit card borrowers). A corporation using structured financing seeks a rating on the commercial paper it issues that is higher than its own corporate rating. This is accomplished by using the underlying loans or receivables as collateral for the commercial paper rather than the issuer's general credit standing. Typically, the corporation (that is, the seller of the collateral) retains some interest in the collateral. Because the corporate entity retains an interest, the NRSROs want to be assured that a bankruptcy of that corporate entity will not allow the issuer's creditors access to the collateral. Specifically, there is a concern that a bankruptcy court could redirect the collateral's cash flows or the collateral itself from the ABCP investors to the creditors of the corporate entity if it became bankrupt.

To allay these concerns, a bankruptcy-remote special entity (SPE) is formed. The issuer of the ABCP is then, the SPE Legal opinion is needed stating that in the event or the bankruptcy of the seller of the collateral, counsel does not believe that a bankruptcy court will consolidate the collateral sold with the seller's assets.

The SPE, is set up as a wholly owned subsidiary of the seller of the collateral. Despite this fact, it is established in such a way that it is treated as a third-party entity relative to the seller of the collateral. The collateral is sold to the SPE which it turn resells the collateral to a conduit (that is, trust). The conduit holds the collateral on the investors' behalf. It is the SPE that holds the interest retained by the seller of the collateral.

The other key party in this process is the conduit's administrative agent. The administrative agent is usually a large commercial bank that oversees all the operations of the conduit. The SPE usually grants the administrative agent power of attorney to take all actions on their behalf with regard to the ABCP issuance. The administrative agent receives fees for the performance of these duties.

ABCP conduits are categorized on two critical dimensions. One dimension involves their level of program-wide credit support either fully or partially supported. The other dimension is as either a single-seller or a multi-seller program. In this section, we will discuss each type.

Fully versus Partially Supported

In a fully supported program, all of the credit and liquidity risk of an ABCP conduit is assumed by a third-party guarantor usually in the form of a letter of credit from a highly rated commercial bank. The ABCP investor's risk depends on the financial strength of the third-party guarantor rather than the performance of the underlying assets in the conduit. Thus, investors can expect to receive payment for maturing commercial paper regardless of the level of defaults the conduit experiences. Accordingly, in determining a credit rating, the NRSROs will focus exclusively on the financial strength of the third-party guarantor.

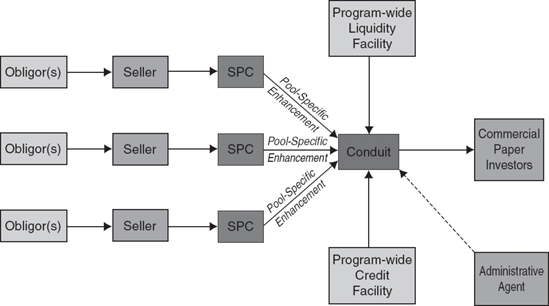

Partially supported programs exposes the ABCP investors directly to credit and liquidity risk to the extent that losses in the conduit exceed program-wide and pool-specific credit enhancements. The conduit has two supporting facilities. The program-wide credit enhancement facility covers losses attributable to the default of the underlying assets up to a specified amount. Correspondingly, the program-wide liquidity facility provides funds to the conduit to ensure the timely payment of maturing paper for reasons other than defaults (e.g., market disruptions). Since investors are exposed to defaults of the underlying assets, the NRSROs make their expected performance under various scenarios a central focus of the ratings process.

Single-Seller versus Multi-Seller Programs

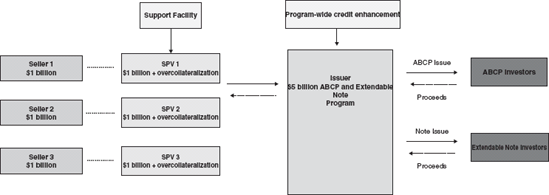

The other key dimension used to categorize ABCP conduits is as either single-seller or multiseller. Single-seller conduits securitize assets purchased from a single seller (e.g., a single originator). Conversely, multiseller conduits pool assets purchased from several disparate sellers and the ABCP issued is backed by the portfolio of these assets.

In a multiseller partially supported ABCP conduit, there are two levels of credit enhancement. The first line of defense is pool-specific credit enhancement that provides protection from the defaults on assets from a particular seller. Pool-specific credit enhancement may include overcollateralization, third-party credit support, or excess spread. The second line of defense is program-wide credit enhancement that provides protection after the pool-specific credit enhancement is depleted. Program-wide credit enhancement is usually supplied by a third-party in the form of an irrevocable loan facility, letter of credit, surety bond from a monoline insurance company, or cash invested in permitted securities (see Fitch, 1999).

Liquidity enhancement is also structured in two levels— pool-specific or program-wide. Liquidity enhancement usually takes the one of two forms. One form of liquidity support is a loan agreement in which the liquidity facility agrees to extend loans to the conduit if maturing paper cannot be rolled over due to say, a disruption in the commercial paper market due to a financial crisis. Note that the liquidity facility is not responsible for interjecting needed funds into the conduit due to defaults in the asset portfolio. The other form of liquidity support is an asset purchase agreement in which the liquidity facility agrees to purchase non-defaulted assets if funds are needed.

Figure 27.1 presents a flow chart illustrating the basic structure of a partially supported, multiseller ABCP program. Note the administrative agent invests no cash into the deal but instead provides a flow of services, as a result, the administrative agent's connection to the conduit is represented with a dashed line.

Extendable commercial paper is a newer development in the asset-backed commercial paper market and a number of conduits have been established or restructured to enable them issuance. The first extendable ABC paper issue was in 2002, from a number of vehicles, including ABN Amro "Tulip" conduit and AIG's Orchard Park and Bluegrass conduits. In many cases extendable commercial paper serves as a backup or substitute to the conventional bank liquidity line on a conduit. In this section we describe a generic extendable ABC paper vehicle.

Extendable Notes

Before we describe an extendable note ABC paper structure, we should consider the form that the notes themselves take. Extendable notes are short-term liabilities issued by commercial paper conduits in the normal way, but with certain structural features that enable them to function more as liquidity reserve facilities rather than typical commercial paper liability.

Extendable notes are issued in the following form: secured liquidity notes (SLNs) and collateralized callable notes (CCNs). SLNs are also referred to variously as liquidity notes, structured liquidity notes and extendable commercial paper notes. An SLN issued by a conduit is a secured note issued with a formal maturity date of up to 397 days from original issuance. (As such, its maturity exceeds the 270 or 364 days maximum maturity of U.S. dollar or euro paper, respectively). The key aspect of the SLN however, is that its expected maturity date is shorter than the formal maturity date. The last expected maturity date of the note will be a function of the underlying assets in the vehicle, and the nature of the cash flows associated with these assets. Generally, the issuer is free to set the expected maturity date in line with its requirements, up to a maximum term in line with the formal maturity date.

On the expected maturity date of the SLN, the issuer will repay the note principal and interest, usually through a rollover issue of new SLNs. At that point, the note is no different from a normal issue of ABC paper. However, if for any reason a new issue of SLNs cannot be placed, then the SLN will not be repaid and instead it will be extended until its final maturity date. This is in effect similar to a liquidity facility; if the SLN cannot be rolled over, underlying assets must be sold to cover repayment on the formal maturity date. So for instance, if an SLN is issued with expected maturity of 90 days, and on the 90th day new SLNs cannot be issued, the SLN remains outstanding from the 91st to the 397th day. During the 307-day period after the expected repay date, underlying assets are sold or amortized, and the proceeds are used to repay the SLNs on or before the 397th day.

The advantage of the SLN facility over a traditional bank liquidity line is that the credit rating agencies assess the cash flow from the underlying assets (needed to repay the SLNs) for the end of the extension period. Hence, no bank liquidity would be required until this period, which would reduce the liquidity fee. Investors also view the extension of SLNs to be an unexpected occurrence, and would treat the initial issue to be normal ABCP in terms of required return.

Therefore, an SLN is essentially an ABC paper issue with an extension feature at the option of the issuer. The most common occurrence is for SLNs to be issued with 90- or 180-day maturities, with a legal final maturity date of 397 days.

A CCN is a collateralized callable note issued with a final maturity date again of maximum 397 days. The CCN has a call option that can be exercised by the issuer on a date prior to the final maturity date. The expected call date will depend on the nature of the cash flows of the underlying assets, but will be for a period inside the 397-day maximum. On the call date, the CCN will be called by the issuance of new CCNs. Again, this is similar to conventional ABC paper. If new CCNs cannot be issued, then the CCN will not be called and it remains outstanding to its final maturity date. Unlike with an SLN, there is a yield penalty: if the issue is not called when expected, its yield is increased (by anything from 10 to 25 basis points) for the remaining term. If the CCN is not called, underlying assets must be realized to repay the proceeds on final maturity.

Investor Perspective

In economic terms, CCNs are identical to SLNs, although investors may view CCNs as more favorable because there is no extension risk associated with them. Also, from the point of view of a rating agency, a callable note that is not called can be considered a not abnormal occurrence, while the extension of a SLN could be construed as a serious negative occurrence.

Where the market has a reasonable idea of the likelihood of an extended note facility actually being used, it is better able to determine how much of a return premium should be demanded by investors. For instance, the view among investors is that the ABN Amro "Tulip" and the Citibank "Dakota" vehicles are highly unlikely to exercise their extension facilities; hence, this paper is treated more or less as conventional ABCP.

Issuer Benefits

By structuring, or restructuring, a conduit with an extendable note facility, issuers can reduce their overall cost of funding. It also gives issuers more flexibility with managing their liquidity requirements and allow for unexpected occurrences.

The main advantages of an extendable note facility are:

The freedom of having a one-year liquidity facility at lower cost than a normal liquidity line.

The flexibility to issue to any term within the 397-day period.

Favorable credit rating agency treatment, who view the extendable notes as 397-day liabilities, thus any liquidity back-up need not kick in until then.

If backed with a traditional liquidity facility, or (in synthetic ABC paper programs) a guaranteed total-return swap (TRS) contract, the extended note facility is viewed very favorably by investors and traded as conventional ABCP.

The credit rating agencies consider its liquidity management capabilities as an essential component when making their rating assessment of a bank. Typically, a rating agency will analyze the following factors in assigning a bank's rating:

Diversity of funding sources.

Structure and maturity of liabilities.

Balance sheet flexibility.

Ability to access the markets for funding in time of correction or illiquidity.

The addition of an extendable note facility to a bank's ABC paper funding vehicles should strengthen the above points from the perspective of the ratings agencies. In fact, a number of banks have set up extendable note ABC paper vehicles or restructured existing vehicles to issue both straight and extendable ABC paper.

Conduit Structuring

It is possible to structure a commercial paper vehicle to issue straight and extendable commercial paper from inception or modify an existing vehicle for subsequent extendable note issuance. In the case of existing conduits that are set up to issue extendable paper, the restructuring can be effected by allowing extendable notes to be issued that are backed with:

A facility to liquidate or amortize underlying assets within the extension period; market value risk of assets not being able to cover liabilities can be hedged through overcollateralization, or a swap arrangement that pays out on any underperformance.

Setting up a TRS with a highly rated counterparty or guaranteed by another bank, that supports the extendable notes on final maturity; a traditional bank liquidity facility that is drawn on to repay notes on final maturity.

A traditional bank liquidity facility is the most expensive option, as it carries with it a standing fee that is payable irrespective of whether the line is ever drawn on.

For existing vehicles, legal documentation describing the conduit structure (the Issue and Paying Agency agreement and the Placement agreement or "Private Placement Memorandum") would need to be redrafted and executed. The redrafted documents would describe the new facility to issue both extendable and straight ABCP.

Figure 27.2 illustrates the structure diagram for a mul-tiseller, multi-SPV combined ABC paper and extendable note program.

There are also well-developed ABCP markets in Europe and Australia. The assets underlying these European ABCP, are similar to those in the United States, namely, trade receivables, consumer loans, credit card receivables, equipment leases, etc. Moreover, there are an increasing number of programs designed to engage in arbitrage in the fixed income market by financing the purchase of asset-backed and mortgage-backed securities with ABCP. Another expanding area is using structured finance to finance cross-border trade receivables for multinational corporations.

Synthetic foreign currency denominated commercial paper allows investors to earn non-U.S. interest rates without exposure to non-U.S. counterparties or political risk. Two examples are Goldman Sach's Universal Commercial Paper or Merrill Lynch's Multicurrency Commercial Paper. The process works as follows. First, a U.S. borrower issues commercial paper in a currency other than U.S. dollars, say British pounds, while simultaneously entering into a currency swap with a dealer. The commercial paper issuer faces no foreign exchange risk because the currency swap effectively allows the issuer to borrow U.S. dollars at British interest rates. Investors can then invest in commercial paper issued by a U.S. counterparty denominated in British pounds.

This chapter examines commercial paper, which is a vehicle for corporations to access short-term funding. The characteristics of commercial paper are discussed, including how it is issued and the secondary market. Investors in commercial paper are exposed to credit risk and most investors rely on the rating agencies to assess this risk. Commercial paper is discount instrument and pays interest at maturity. The process for issuing asset-backed commercial paper is also discussed. Finally, an overview of commercial paper denominated in currencies other than U.S. dollars is presented.

Adelson, M. H. (1993). Asset-backed commercial paper: Understanding the risks. New York: Moody's Investor Services, April.

Coen, M. R., Lee, W., and Maas, B. (2000). ABCP market overview: ABCP enters the new millennium. New York: Moody's Investors Service.

Dierdorff, M. D. (1999). ABCP market overview: Spotlight on changes in program credit enhancement and growth and evolution of securities arbitrage programs. New York: Moody's Investors Service.

Fabozzi, F. J., Mann, S. V., and Choudhry, M. (2002). Global Money Markets. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

FitchRating. (1999). Understanding asset-backed commercial paper. New York: Fitch.

Marc, R. S., and Strahan, P. E. (1999). Are banks still important for financing large businesses? Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Current Issues in Economics and Finance, August: 1-6.

Stojanovic, D., and Vaughan, M. D. (1998). Who's minding the shop? Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, The Regional Economist, April: 1-8.