LAURIE S. GOODMAN, PhD

Co-head of Global Fixed Income Research and Manager of U.S. Securitized Products Research, UBS

Abstract: Reverse mortgages are instruments designed for older homeowners; they allow the equity in a home to be monetized. At the initiation of the reverse mortgage, a homeowner elects to take out either a lump-sum payment, a fixed monthly payment for life, or can have access to a line of credit. The reverse mortgage loan must be paid in full when the last surviving borrower dies, moves, or sells the home.

Keywords: reverse mortgage, home equity conversion mortgage (HECM)

Reverse mortgages are a type of residential mortgage instrument which allows homeowners to monetize the equity in their home. This chapter describes the characteristics of this type of mortgage. Reverse mortgages, while still a very small part of the U.S. mortgage market, has shown robust growth. Moreover, with changing U.S. demographics, their popularity is expected to increase.

In a reverse mortgage, the homeowner receives cash, either as an up-front payment, as a monthly payment, or as a line of credit. That money is not taxable (technically, it is considered a loan advance, not income), and can be used to live on. It does not impact Medicare or Social Security benefits. It could potentially impact Medicaid benefits. The loan amount will depend on the age of the borrower (younger borrowers receive less money), the appraised home value, current interest rates, and the lending limit in a particular area, if applicable. The mortgages can be prepaid at any time.

Reverse mortgage loans are generally payable in full when the last surviving borrower dies or sells the home. The mortgage may also come due if:

The borrower permanently moves to a new principal residence.

The last surviving borrower fails to live in the home for 12 months in a row due to physical or mental illness.

The property deteriorates, except for reasonable wear and tear, and the borrower fails to correct the problem.

The borrower fails to pay property taxes or hazard insurance or violates any other borrower obligation.

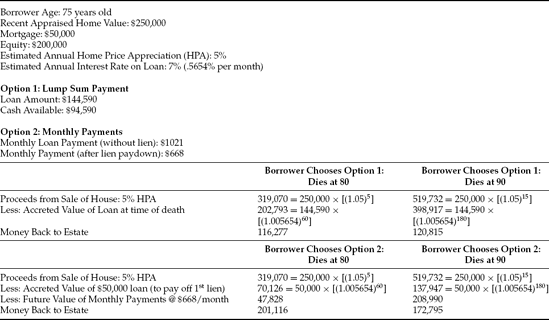

A simplified example, shown in Table 19.1 will make this more clear. A 75-year-old borrower has taken out a reverse mortgage. Assume the house is now worth $250,000; the borrower has $200,000 of equity and a mortgage for $50,000. This simplified example neglects up-front fees, mortgage insurance (when applicable), assumes a fixed interest rate (when interest rates on this product are generally variable), and gives the borrower a choice of only two payment options: taking the cash all up front or taking the cash in the form of a monthly payment up front. If the borrower chooses to take out a payment up front in lump-sum form (option 1), then based on age, value of home, and interest rate, the maximum amount that can be received up front is $144,590. The borrower must then apply $50,000 to pay down the first mortgage. That frees the borrower from making further interest payments on the mortgage, and leaves the borrower with $94,590 of cash. By contrast, if the borrower chooses the monthly payment option (option 2), the mortgage will be paid off, and the borrower will receive a monthly payment of $668. (Note that if there was no first lien, the borrower would have received $1,021 per month.)

Table 19.1 first looks at the case in which the borrower elects to take option 1, the up-front payment, and dies at 80, exactly 5 years (60 months) after taking out the loan. In this illustration it is assumed the house has appreciated by 5% per annum, and is now worth $319,070. The loan ($144,590) must be repaid with interest. Assuming an annual interest rate of 7% (equivalent to a monthly rate of 0.5654%), the estate must repay $202,793 (144,590 × ((1.005654)60)). Thus, the $116,277 difference ($310,070 house value - $202,793 loan repayment) flows back to the estate. The far right section of Table 19.1 shows the scenario in which the borrower elects to take the up-front payment, and dies at age 90, exactly 15 years (180 months) after taking out the reverse mortgage. We assume the value of the house is $519,732 (reflecting 15 years of 5% home price appreciation) and the accreted value of the loan is $398,917. Thus, $120,815 reverts to the estate.

Now let us consider the case in which the borrower elects the monthly payment option (option 2). The borrower must take $50,000 up front in order to pay off the first lien. Given the borrower's age, appraised home value, interest rate, and so on, our borrower can receive a payment of $668 per month. Thus, when the borrower dies, both the accreted value of the loans plus the future value of the monthly payments must be subtracted from the terminal value of the property. If the borrower dies at 80, exactly 60 months after the mortgage was taken out, the borrower would owe $47,828, the future value of 5 years (60 months) of monthly payments, plus an accreted loan amount of $70,126 (on the original $50,000 loan). Thus, $201,116 reverts back to the estate ($319,070 from the sale of the house—$70,126 to pay back the cash lien—$47,828, the future value of the monthly payment stream). If the borrower dies at 90, the value of the property would be higher, but the future value of the original $50,000 loan would be higher, and a lot more monthly payments have been made to the borrower. Under these circumstances, Table 19.1 shows the estate is then left with $172,795.

There are three basic types of reverse mortgage programs:

Home equity conversion mortgage (HECM)

Fannie Mae Home Keeper (FMHK) mortgages

Proprietary reverse mortgage products

The HECM program is offered by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), a division of the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and all HECM mortgages are FHA insured. This is by far the largest of the reverse mortgage programs, and has experienced very robust growth. In fiscal year 2003, there were only 18,097 reverse mortgage loans endorsed. This number doubled to 37,829 loans in fiscal year 2004, then increased rapidly to 43,131 in fiscal year 2005, and 76,351 in fiscal year 2006. In the first nine months of fiscal year 2007, 80,425 reverse mortgage loans were endorsed—more than for the entire year 2006.

To be eligible for an HECM loan, a borrower must be aged 62 or over and live in the home as a principal residence. Empirically, we find that most of the borrowers that take out HECM loans are considerably older than the minimum age. In fact, HUD reports that the median age of an HECM borrower was 75; the median age of all elderly homeowners is 72. The home must be a single-family residence in a one- to four-unit dwelling, a condominium, or part of a planned unit development (PUD). Some manufactured housing is eligible. The overwhelming majority (approximately 85%) of these are single-family properties.

Payment Options

An HECM mortgage can be taken out in any of the following forms:

Tenure: Equal monthly payments as long as at least one borrower lives and continues to occupy the property as a principal residence.

Term: Equal monthly payments for a fixed number of months selected.

Line of credit: Unscheduled payments or installments, drawn down at times and in amounts of the borrower's choosing until the line is exhausted. This line will grow over time.

Modified tenure: Combination of line of credit and monthly payments for as long as the borrower remains in the home.

Modified term: Combination of a line of credit and monthly payments for a fixed period.

In practice, the line of credit is the most popular option. If a borrower wants to take out money immediately (to pay off a first lien, or take a vacation) it is considered to be a drawdown on the line of credit. In our simplified example in Table 19.1, we wanted to show deterministically how the reverse mortgage would impact the estate. Thus, we included only two options: a line of credit in which the amount was drawn down immediately, and a modified tenure, in which the up-front payment was used to pay off the first lien. In reality, borrowers have far more flexibility than we indicated in our example.

Under the conditions of a reverse mortgage, when the house is sold or no longer used a primary residence, the borrower or their heirs will repay the drawn portion of the credit line (or monthly payments) plus interest to the lender. The remaining value of the house belongs to the estate. It is possible that home price appreciation might be low enough, and the borrower might live long enough, that the price of the house is less than the accreted value of the outstanding loans. For example, assume in Table 19.1 that our 75-year-old borrower selected option 2, receiving a $50,000 up-front payment to cover the first lien, and additional payments of $668 per month. If that borrower died at 90, $346,937 ($137,947 from the up-front loan and $208,990 from the monthly payments) would be owed. If the house value had appreciated 2% per annum (rather than the 5% we assumed in Table 19.1), the appreciated house value would be $336,467, or approximately $10,500 less than the amount due on the reverse mortgage. From on investor's point of view, this is not an issue: Government insurance would cover this, as the loans are FHA insured. From a borrower's point of view, it is also not a concern, as the loans are nonrecourse.

The interest rate on the HECM loan is generally reset either monthly or annually, based on the following reset formula: one-year CMT + a margin, where CMT is the constant maturity Treasury.

In addition to the interest expense, the borrower must pay a mortgage insurance premium (MIP) for the FHA insurance. This premium is equal to 2% of the up-front amount plus an annual premium equal to 0.5% of the loan amount. The MIP is meant to guarantee that if the loan servicer goes bankrupt, the government will step in and make future payments. The MIP also guarantees that if there is any shortfall between sales price and repayment amount, the government will make up the difference. In addition to the MIP, reverse mortgages also carry application fees, origination fees, and often a monthly servicing fee. These charges are generally paid by the reverse mortgage, and the costs are added to the principal and paid at the end, when the loan is due.

Amount that Can Be Borrowed

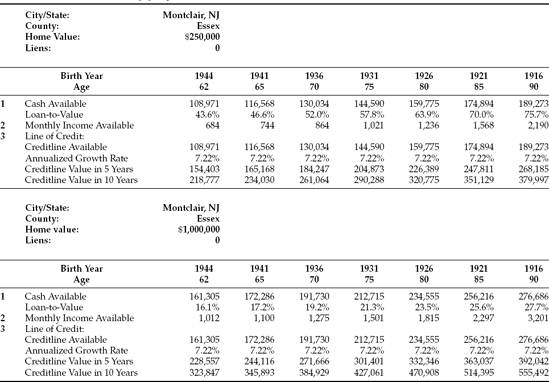

The amount that can be borrowed depends on a borrower's age, the current interest rate, and the appraised value of the home. Moreover, the maximum size of an HECM mortgage will depend on the maximum HUD loan limit. This varies by county and is adjusted annually. Currently, the maximum is $362,790 for single-family homes in high-cost areas and $200,160 for rural areas. That is, the limit in high-cost areas is 87% of the conventional limit of $417,000. It is 48% of the conventional limit in low-cost areas. The implications of these limits are clear—if two borrowers of the same age applied for a loan at the same time, one with a home value of $362,790 and another with a home value of $1 million, they would both receive exactly the same HECM loan. When there is more than one borrower, the loan amount in an HECM mortgage is determined solely by the age of the younger borrower.

Table 19.2 illustrates the amount that can be drawn out under the HECM program. These calculations assume the home is located in a high-cost area. Thus, if a home were appraised for $250,000, the top section of Table 19.2 indicates a 65-year-old borrower would have a credit line available for $116,568; the credit line would be $144,590 if the borrower were 75, and $174,894 if the borrower were 85. Similarly, if the tenure option were selected, a 65-year-old borrower would receive $744/month, a 75-year-old borrower would receive $1,021/month, and an 85-year-old borrower would receive $1,568/month. If the home appraised for $1 million, the FHA loan limits would be binding, limiting the amount the borrower could receive. Thus, as indicated in the bottom section of Table 19.2 a 65-year-old borrower would have a credit line of $172,286, which is only 46% higher than that available on a $250,000 home.

The Fannie Mae Home Keeper mortgage program is Fannie Mae's conventional market alternative to the HECM product. It works much like an HECM; the borrower can receive fixed monthly payment for life (that is, for as long as the borrower occupies the home as his/her principal residence), a line of credit, or any combination of monthly payments or a line of credit. However, the Fannie Mae Home Keeper can be used for a broader array of alternatives, including condominiums that are not FHA-approved and new home purchases. The latter is particularly important, as HECM Mortgages require that borrowers have been in their home for at least a year. Let us assume a 75-year-old man wants to sell his home in Philadelphia, with a value of $150,000, and buy a $200,000 home in Florida. To avoid a mortgage payment on the new home (as the borrower's income is very limited), the borrower would have to use the entire $150,000 proceeds from the sale of the Philadelphia home, plus another $50,000 in savings. If the borrower does not have the $50,000, he could not buy the new home (unless he qualifies for and is able to obtain a regular mortgage). But the borrower could seek an FMHK reverse mortgage, which can be used to bridge the $50,000 difference.

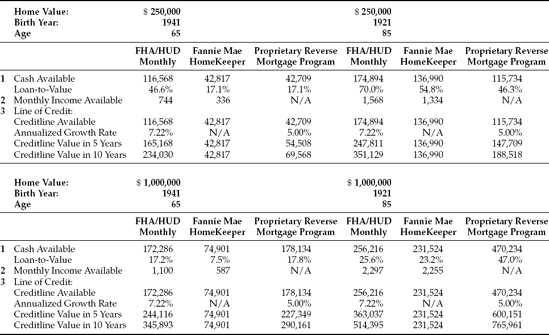

Note that even though the loan limits are higher for Fannie Mae programs than the FHA programs, the amount that can be drawn out under the Fannie Mae Home Keeper program is usually less than what can be drawn out under the HECM program. This is illustrated in Table 19.3. A 65-year-old borrower with a home worth $250,000 could draw out $116,568 under the HECM program, while the Fannie Mae Home Keeper would allow only $42,817.

The interest rate on the Home Keeper mortgage is determined as a spread above an index rate—the current weekly average of the one-month secondary market CD rate, which is published by the Federal Reserve. The rate on the Fannie Mae Home Keeper mortgages adjusts monthly.

There are a number of lenders that offer proprietary mortgage products. As on the HECM and FMHK products, the interest rates are variable. These proprietary products generally build in additional protections to make sure the accreted value of the loans will not be higher than the home value. First, these proprietary products do not have a tenure option, as the lenders are unwilling to absorb the risk that the borrower will live long enough that total payments may be higher than the value of the house. Second, the growth rate on the line of credit may be freely altered by the lender. These protections are important to the investor, as there is no government guarantee on these loans.

From the borrower's perspective, the big advantage of the proprietary products is that they do not have a loan limit. Thus, for a home with a high appraised value, the borrower is often better off with a proprietary product. This can be seen in Table 19.7, which compares the HECM product with a proprietary reverse mortgage offering from one major originator of reverse mortgages. Note that for a home valued at $250,000, the HECM product gives the borrower (regardless of age) a much larger line of credit than the proprietary product offered. For a home valued at $1 million, a 65-year-old borrower can have a marginally larger line of credit using the proprietary product ($178,134 versus $172,286). An 85-year-old borrower would have a huge advantage using a proprietary product versus an HECM ($470,234 versus $256,216).

This chapter provides a brief introduction to the reverse mortgage market. Reverse mortgage products have become much more popular and will continue to grow in importance. This growth will be further aided by changing demographics. Moreover, securitization activity is building, allowing for broader mix of investors to hold these instruments. As reverse mortgage products grow in popularity, we expect the number of originators offering them, as well as their securitization volumes, to increase.

Davidoff, T. (2004). Maintenance and the home equity of the elderly. Fisher Center for Real Estate and Urban Economics, paper no. 03−288. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley—Haas School of Business.

Davidoff, T., and Welke, G. (2007). Selection and moral hazard in the reverse mortgage market. Haas School of Business working paper, 1−39.

DiVenti, T. R., and Herzog, T. N. (1992). Modeling home equity conversion mortgages. Transactions of the Society of Actuaries A3: 101−115.

Fitch Ratings. (2005). Repay My Mortgage? Over My Dead Body! - Fitch's Reverse Mortgage Criteria. New York: Fitch Ratings.

Mayer, C, and Simons, K. (1994). Reverse mortgages and the liquidity of housing wealth. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association 22, 2: 235-255.

Miceli, T. J., and Sirmans, C. F. (1994). Reverse mortgages and borrower maintenance risk. Real Estate Economics 22,2: 257-299.

Rodda, D. T., Lam, K., and Youn, A. (2004). Stochastic modeling of federal housing administration home equity conversion mortgages with low-cost refinancing. Real Estate Economics 32, 4: 589-617.

Shiller, R., and Weiss, A. (2000). Moral hazard in home equity conversion. Real Estate Economics 28, 1: 1-31.

Stucki, B. R. (2006). Using reverse mortgages to manage the financial risk of long-term care. North American Actuarial Journal 10, 4: 13-15.

Szymanoski, E. J. (1994). Risk and the home equity conversion mortgage. Journal of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association 22, 2: 347-366.

Szymanoski, E. J., Enriquez, J. C, and DiVenti, T. R. (2007). Home equity conversion mortgage terminations: Information to enhance the developing secondary market. Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research 9, 1: 5-45.

Venti, S., and Wise, D. (2000). Aging and housing equity. National Bureau of Economic Research, working paper 7882.

Zhai, D. H. (2000). Reverse mortgage securitizations: Understanding and gauging the risk. Moody's Investors Service, June 23.