JOHN D. FINNERTY, PhD

Professor of Finance and Director of the MS in Quantitative Finance Program, Fordham University Graduate School of Business

Managing Principal, Finnerty Economic Consulting, LLC

Abstract: Securities innovation is the process of developing positive net present value financing instruments. Securities innovation improves capital market efficiency by offering more cost-effective means of transferring risks, increasing liquidity, and reducing transaction costs and agency costs. It is a profit-driven response to changes in the economic, tax, and regulatory environment. It involves the design of financial instruments that are better in that they either provide superior, previously unavailable risk-return combinations or furnish the desired future cash-flow profile at lower cost than existing instruments. This often includes combining new derivative products with traditional securities to manage risks more cost effectively. The key to developing better risk-management vehicles is to reallocate risk more cost effectively. Innovations thrive when they provide real value. A new financial instrument is truly innovative only if it makes issuers and investors better off than they were before the new security was developed.

Keywords: securities innovation, risk reallocation, financial engineering, agency costs, clientele effect, asset securitization, debt innovations, preferred stock innovations, convertible securities innovations, common equity innovations, primary capital, mortgage-backed securities, stripped mortgage–backed securities, mortgage pass-through certificates, collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), credit card receivable–backed securities, reserve-fund structure, shifting-interest structure, automobile loan–backed certificates, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collateralized bond obligations, collateralized loan obligations, basket default swap, pay-in-kind debentures (PIKs), toggle PIKs, zero-coupon bonds, adjustable-rate notes, floating-rate notes (FRNs), dual-currency bonds, indexed-currency option notes, principal exchange rate–linked securities, reverse principal exchange rate–linked securities, alternative risk transfer (ART), insurance-linked notes (ILNs), catastrophe bonds, global bonds, extendible notes, hybrid capital securities, inverse floaters, interest rate reset notes, credit-sensitive notes, floating-rate, rating-sensitive notes, puttable bonds, increasing-rate notes, euronotes, euro-commercial paper, premium bonds, variable-coupon renewable notes, supermaturity bonds, commodity-linked bonds, covered bonds, equity contract notes, equity commitment notes, structured products, structured notes, structured swaps, hybrid capital security, leveraged inverse FRNs, collared FRN, credit-linked note (CLN), adjustable-rate preferred stock, convertible adjustable preferred stock, auction-rate preferred stock, money market preferred stock, remarketed preferred stock, variable cumulative preferred stock, gold-denominated preferred stock, mandatory convertible preferred stock, preferred equity redemption cumulative stock, dividend enhanced convertible stock, preferred redeemable increased dividend equity security (PRIDES), puttable convertible bonds, zero-coupon convertible debt, convertible-exchangeable preferred stock, adjustable-rate convertible debt, liquid yield option notes, ABC Securities, synthetic convertible debt, conversion price reset notes, convertible interest-rate-reset debentures, contingent convertible bonds, cash-redeemable LYONs, cash-settled convertible notes, Americus trust, SuperShares, unbundled stock units (USUs), callable common stock, puttable common stock, master limited partnerships

Securities innovation is the process of creating positive-net-present-value financial instruments. It has brought about revolutionary changes in the array of available financial instruments. Many factors stimulate this process, the more important of which are interest rate and exchange rate volatility, tax and regulatory changes, globalization of the capital markets, deregulation of the financial services industry, and increased competition within the investment banking industry.

Designing innovative financial instruments to solve financial problems is referred to as financial engineering (Finnerty, 1988, 1992). A new financial instrument is innovative when it makes both issuers and investors better off than they were with previously existing securities. An innovative security helps the capital markets operate more efficiently or makes them less incomplete (Van Horne, 1985; Ross, 1989; Merton, 1992). It enables market participants to either accomplish something more efficiently or accomplish something they could not achieve previously. Often, the objective has been more cost-effective hedging vehicles. The challenge for a prospective issuer or investor is to determine whether the new security is truly innovative or just looks different and is intended only to enrich the investment bankers who are promoting it!

Innovations thrive when they provide real value. For example, financial futures have enjoyed ever-expanding growth since their inception in the early 1970s. Other innovations, such as deferred-interest debentures, were issued in large volume for a brief time but have since been issued only infrequently—because changes in tax law eliminated their advantages or more recent innovations superseded them. Still others, such as zero-coupon bonds, were issued in large volume in one form, virtually disappeared because of a change in tax law or regulation, and then reemerged in a new form—liquid yield option notes (LYONs)/zero-coupon convertible debt, which became popular. Extendible notes, medium-term notes, mandatory convertible preferred stock, collateralized mortgage obligations, and fixed-rate capital securities are among the innovations that have thrived.

Numerous securities innovations have been designed to circumvent provisions of the tax code or regulation. Miller (1986) likens the role of regulation in stimulating innovation to that of the grain of sand in the oyster. Since few things in this world are as mutable as the current tax code or a set of investment regulations, securities intended to overcome such obstacles are likely to disappear along with the tax or regulatory quirk that gave rise to them. But just as quickly, new tax or regulatory provisions will spawn a new round of securities innovation.

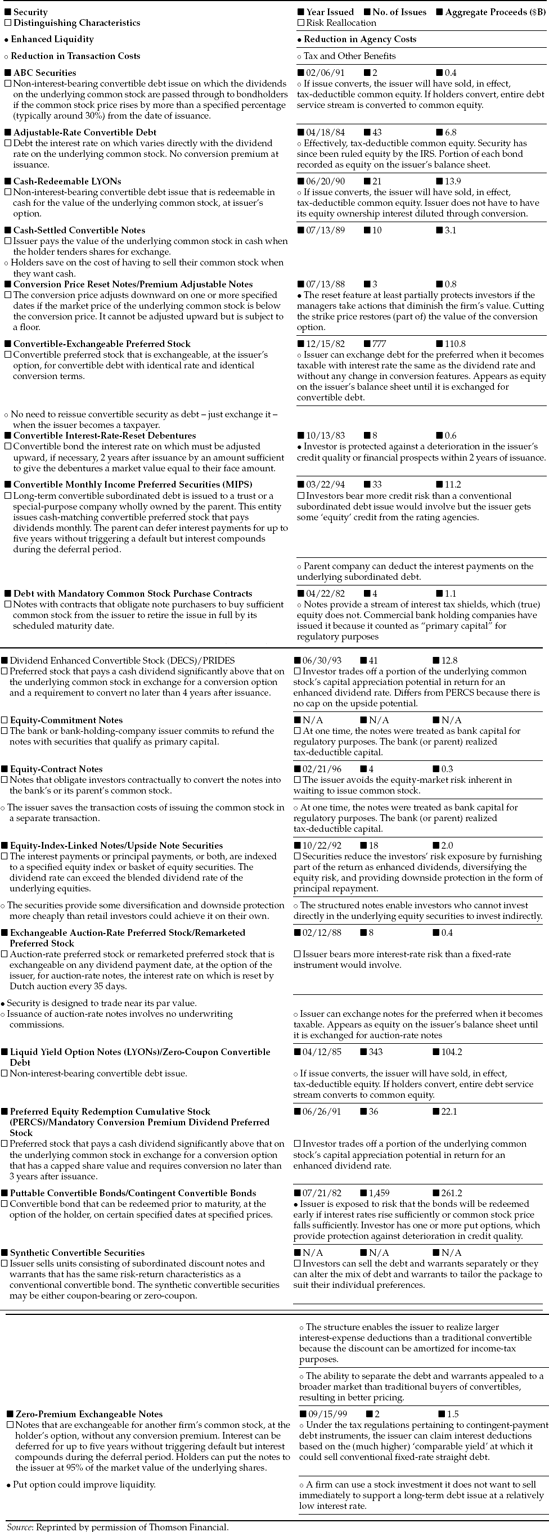

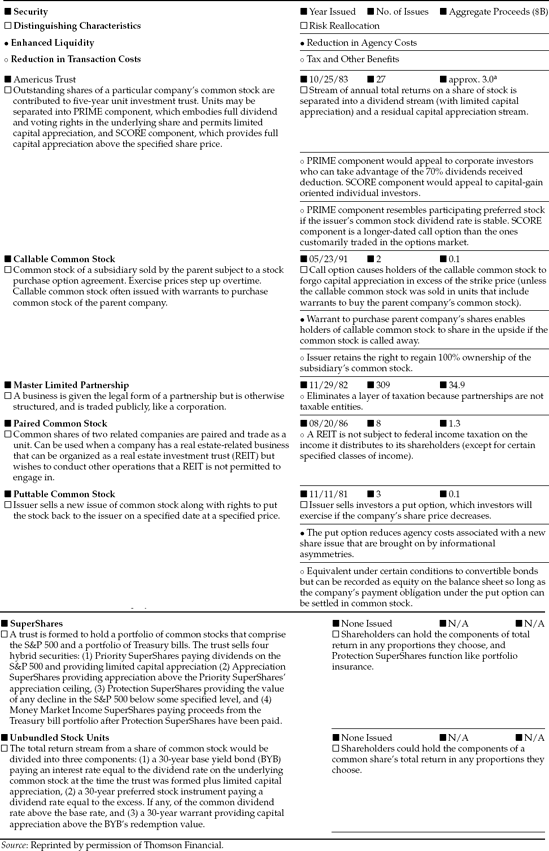

This chapter provides a survey of innovative corporate securities through July 2007. (For earlier surveys, see Finnerty [1988, 1992] and Finnerty and Emery [2001, 2004].) It identifies the sources of value added of the more significant recent innovations and, for the reader's convenience, retains the descriptions of the most significant past innovations. Innovations are categorized as one of four types of instruments: (1) debt; (2) preferred stock; (3) convertible securities; and (4) common equity. The updated tables describe a total of some 80 distinct new securities we have been able to identify. For each security, the tables provide a brief description of its distinctive features, probable sources of value added, the date of first issue, and an estimate of the number of issues and total new issue volume for each security through July 2007. The value added offers reasons for the "staying power" for enduring securities and the lack of innovation in failed securities.

Securities innovation can add value in the following ways:

Reallocate some form of risk from issuers or investors to other market participants who are either less risk averse or else willing to bear them at a lower cost.

Increase liquidity.

Reduce agency costs arising from conflicts of interest among the firm's stakeholders.

Reduce issuers' underwriting fees and other transaction costs.

Reduce the combined taxes of issuer and investors.

Circumvent regulatory restrictions or other constraints on investors or issuers.

Most debt innovations (see Table 7.1) involve some form of risk reallocation as compared to conventional debt instruments. Risk reallocation, as mentioned, adds value by transferring risks to others better able to bear them. It may also be beneficial to design a security that better suits the risk-return preferences of a particular class of investors. Investors with a comparative advantage in bearing certain risks will pay more—or, alternatively, have a lower required return—for innovative securities that allow them to specialize in bearing such risks.

For example, suppose an oil producer issued "oil-indexed" debt with interest payments that rise and fall with oil prices. It might have a lower required return for two reasons: (1) the firm's after-interest cash flows will be more stable than if it issued straight, fixed-rate debt, thereby reducing default risk; and (2) some investors may be seeking a "play" on oil prices not otherwise available in the financial markets.

It is clear that investors are willing to pay more for "scarce" securities they value highly. Financial intermediaries have earned considerable profits by simply buying existing securities, repackaging their cash flows into new securities, and selling the new securities (Ross, 1989). The success of stripped U.S. Treasury and municipal securities (created by separating the coupon payments from the principal repayment) illustrates how the sum of the value of the parts can exceed the whole. The benefits were so great that the U.S. Treasury decided to capture for itself the profits that securities dealers were making from it and began issuing registered Treasury STRIPS (separate trading of registered interest and principal of securities). STRIPS permit the coupon and principal payments to be registered and traded separately. In another example, investment banks purchase portfolios of mortgages from originating institutions and place them in trusts or special purpose corporations. The new entities then issue mortgage pass-through certificates. The investment bank gets the difference (with an important exception noted later) between the payments the entity gets and those it pays out. Issuers may be able to capture such benefits for themselves by designing new issues of securities appropriately.

Like mortgage pass-through certificates, credit card receivable–backed securities and automobile loan–backed certificates are undivided ownership interests in portfolios of credit card receivables and consumer automobile loans. Such securities allow the originator to transfer the loan's interest rate risk and default risk (or at least a portion of it) to others. The investors' required return is lower because of the diversification benefit from the pooling.

Managing Reinvestment Risk

Pension funds face reinvestment risk when they reinvest interest payments received on standard debt securities. Zero-coupon bonds were designed in part to appeal to such investors because they eliminate reinvestment risk by having no interest payments to reinvest. Instead, interest compounds over the entire life of the security.

Managing Prepayment Risk

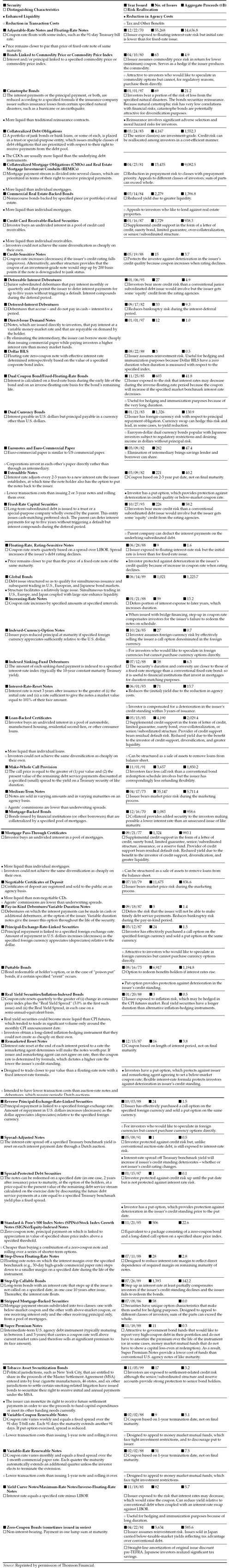

Most mortgages are prepayable at par at the option of the mortgagor. Both collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs) and stripped mortgage–backed securities address this "prepayment" risk, which investors in mortgage pass-through certificates find troublesome (Fabozzi, 1989, 1995). CMOs repackage the payment stream from a portfolio of mortgages into several series of debt instruments—sometimes more than five dozen—that are ordered by the repayment of principal. In the simplest form of CMO, each series is to be repaid in full before any principal repayment is made to holders of the next series (see Figure 7.1). By so doing, such a CMO effectively shifts most of the mortgage prepayment risk to the lower-ordered classes, and away from the higher-ordered classes.

CMOs are designed to take advantage of the segmentation and incompleteness of the bond market. Prepaid mortgages are not a problem for money market mutual funds and other short-term investors, whereas pension funds and other long-term investors do not want mortgages prepaid. By carving up the payment stream and prioritizing the right to receive payments, the CMO structure creates fast-pay classes that appeal to short-term investors and slow-pay classes that appeal to long-term investors.

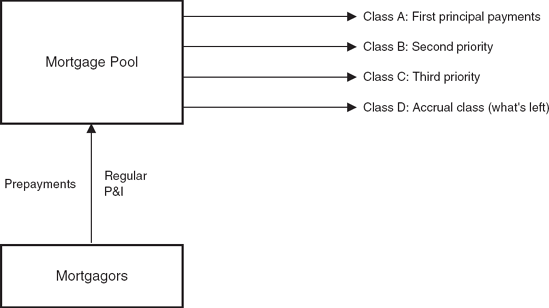

Planned amortization class (PAC) bonds and targeted amortization class (TAC) bonds refined mortgage-backed securities to further reduce prepayment risk (Perlman, 1989). PAC bonds repay principal according to a given schedule so long as pool prepayments remain within a specified range, for example, 100% PSA to 300% PSA. (The PSA Standard Prepayment Model assumes that mortgages prepay at the annualized rate of 0.2% during the first month, the prepayment rate steps up in increments of 0.2% each month until month 30, and prepayments remain constant at 6% per year for all succeeding months.) Thus, they provide a predictable cash flow over a wide range of interest rate scenarios. It is important to appreciate that prepayment risk is not eliminated; it is reallocated, and other pool classes—companion classes—acting as prepayment "shock absorbers," bear most of the pool's prepayment risk.

TAC bonds evolved from PAC bonds. Figure 7.2 shows how PACs and TACs reallocate prepayment risk. They are targeted to a narrower range of prepayment rates. Both rely on companion classes to function as prepayment shock absorbers. PACs get two shock absorbers and TACs get one.

Stripped mortgage–backed securities or mortgage strips divide the payment stream from a pool of mortgages (or mortgage securities) into two (or in some cases more than two) securities. The IO strips get all the interest and the PO strips get all the principal. When prepayments accelerate, PO strips, which have large positive durations, increase in value because principal is received sooner. IO strips, which have large negative durations, decrease in value because the total interest paid is reduced. Understandably, both have high price volatility.

The introduction of these securities also enhanced market completeness because of their duration and convexity characteristics. PO strips are recognized as "bullish" investments because a decrease in interest rates, which benefits bond prices generally, tends to boost prepayments and hence PO strip prices. IO strips are recognized as "bearish" investments because their prices move in the opposite direction. Mortgage strips are ideal for speculation on prepayment rates or hedging prepayment risk. For example, the risk that a slower prepayment rate (say, due to an increase in interest rates) will reduce the value of a mortgage portfolio can be hedged by buying IO strips. Those wanting to protect a portfolio of high-coupon mortgages against rising prepayments can purchase high-coupon PO strips.

Another innovation for managing prepayment risk is the make-whole call provision, which is an indexed bond call option (Emery, Hoffmeister, and Spahr, 1987). The strike price is indexed to the yield on a comparable duration Treasury bond. The make-whole call provision reduces the security holder's (rather than the issuer's) prepayment risk. Quaker Oats was the first to use this provision in a public debt issue, in October 1995. Since then, it has grown to become virtually standard forinvestment-grade corporate bonds (Mann and Powers, 2001). For the most part, non-investment-grade corporate bonds that include a call provision have continued to use the fixed-price provision.

Managing Default Risk

Asset-backed securities reduce default risk through diversification. They can also reallocate default risk by prioritizing the right to receive payments from a portfolio of risky securities, such as bonds or bank loans.

An issuer of asset-backed securities, such as a mortgage, automobile, or credit card lender, can retain default risk by providing a limited corporate guarantee, overcollater-alizing (by pledging additional assets), or taking a subordinated position. Also, the issuer of the asset-backed security can purchase a guarantee, letter of credit, surety bond, or similar promise of payment from a creditworthy third party.

There are several possible structures for reallocating default risk. With the pass-through structure, the loans are transferred to a special purpose entity (SPE) in exchange for pass-through certificates, which are proportional ownership claims that are sold to investors. The originator/seller can overcollateralize by selling less than 100% of the claims. All payments are collected by the trustee and are passed through to investors on the specified payment dates. If needed, the trustee can draw on credit enhancement mechanisms, such as a reserve fund or a line of credit. The pass-through structure has been used to securitize residential mortgage loans, commercial mortgage loans, automobile installment loans, credit card receivables, recreational vehicle installment loans, equipment leases, boat installment loans, manufactured housing installment loans, and home equity loans.

With the pay-through structure, the loans are transferred to an SPE and provide collateral for SPE-issued notes. The pay-through structure permits the seller/servicer to modify the cash flows received on the underlying collateral. The restructuring is particularly useful when nonmarket, incentive interest rate automobile loans are securitized. Such a structure has been utilized to provide automobile loan–backed and truck loan–backed securities with fixed sinking-fund schedules, which transfers the certificate holder's exposure to prepayment risk to the holders of the SPE's residual interest.

Credit card receivables are handled differently. Because of high payment rates, a credit card receivable–backed issue would mature within about a year if all the payments were passed through. To create an intermediate-term security, credit card receivable–backed certificates typically pay only interest for a specified period, normally 24 to 60 months. Principal payments received during this revolving period are reinvested in newly generated credit card receivables. Typically more receivables are sold to the trust than are sold to investors. The seller/servicer is required to retain a specified minimum ownership of the difference, typically between 5% and 10%.

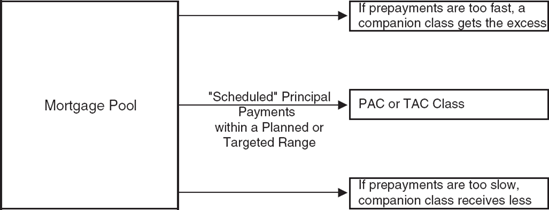

Senior-Subordinated Structure for Reallocating Default Risk of Asset-Backed Securities With senior/subordinated mortgage-backed securities, senior certificate holders have first claim on the trust's cash receipts. A shortfall in payments to senior certificate holders is prespecified to be handled by one of two possible structures. In the reserve-fund structure, the originator establishes a reserve fund either fully at issuance or else by contributing between 0.10% and 0.50% of the original pool balance at issuance and then capturing the excess yield spread until the reserve is fully funded. In the latter case, subordinated certificate holders get no cash until the fund builds up to a prespecified level, typically 1% to 2% of the pool balance for mortgages, and up to 4% to 5% for automobile loans. The reserve fund is then used to cover any senior certificate payment shortfall. Capturing excess spread in a reserve fund is a key form of credit enhancement in agency MBS deals. In the shifting-interest structure, shortfalls are met by transferring the amount from the subordinated certificate ownership percentage to the senior certificate ownership percentage. Figure 7.3 compares the two senior-subordinated structures. The shifting-interest structure is usually found only in retail MBS deals. Of course, the reserve-fund structure insures that cash flows to senior certificate holders will be as promised, whereas the shifting-interest structure compensates senior certificate holders through a change in future distributions.

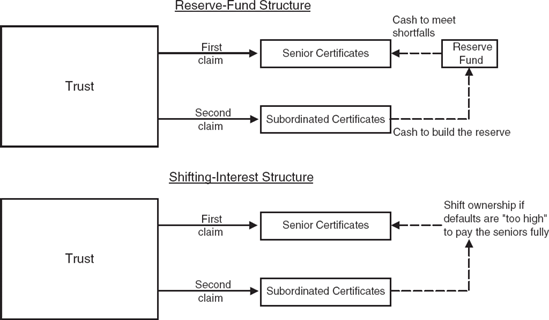

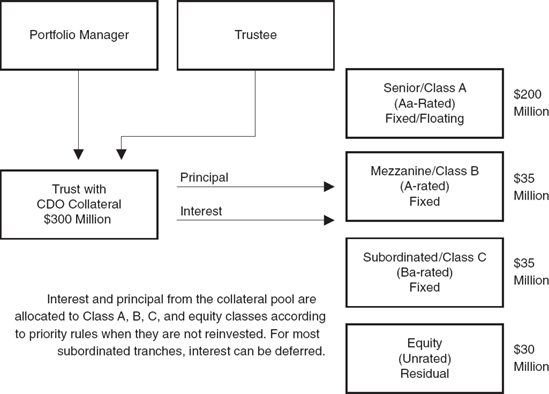

Collateralized Debt Obligations Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) consist of multiple bond classes and an equity class which are backed by a portfolio of debt obligations, such as bonds (in which case they are sometimes referred to as collateralized bond obligations) or bank loans (in which case they are referred to as collateralized loan obligations). The issuer is a bankruptcy-remote trust. The securities are prioritized with respect to the cash flows from the underlying portfolio in decreasing order: senior tranches, mezzanine tranches, subordinated tranches, and equity tranche, as illustrated in Figure 7.4. The equity tranche takes the first loss and receives all residual cash flows after the payment of all expenses such as administrative and management fees and payments to debt classes in the structure.

CDOs do for default risk what CMOs do for prepayment risk. In both cases, the structure provides a diversification benefit. It also enables investors to choose securities that are most suitable for their specific risk/return preferences.

CDOs are of three basic types, cash flow, market value, and synthetic (CDO Primer, 2004; Lucas, Goodman, and Fabozzi, 2006). The cash flow structure is built around a portfolio of regular-cash-paying debt instruments. It can handle a great variety of liability types. The portfolio is usually actively managed so as to eliminate liabilities whose credit is deteriorating. The synthetic structure uses credit default swaps or basket default swaps to replicate a cash flow CDO. A basket default swap has a portfolio of assets as the underlying, whereas it is usually a single asset with a credit default swap. The portfolio is either static or else allows, at most, limited substitutions. The synthetic structure is more cost effective than the cash-flow variety when designed to take advantage of favorable pricing in the swap market. The market value structure is designed to take advantage of anticipated security price volatility. It has been used to securitize hedge fund and private equity investments.

Pay-in-Kind Debentures (PIKs)

Pay-in-kind debentures (PIKs) were popular in the 1980s in financing leveraged buyouts. The firm was permitted to issue additional notes (identical to the original notes), rather than pay interest in cash, but could still claim the interest tax deduction. The firm could defer paying cash until it had paid down its more senior debt, thus achieving higher leverage. A tax change in 1986 made it very difficult to get the tax deduction, and PIK issuance dried up. PIKs recently made a comeback in a slightly different form, called toggle PIKs. The firm can "toggle" back and forth between paying cash and issuing additional notes, but if it chooses to issue notes, the coupon is higher than if it pays cash. Toggling back to cash at the right time could avoid the tax problem that initially curtailed their issuance. However, investors eventually began to object to the agency problem inherent in the toggle feature: There was nothing to prevent a dicey credit from flipping the note toggle immediately and never switching back.

Managing Interest Rate Risk

Adjustable-rate notes and floating-rate notes (FRNs) are among the many innovative debt securities that manage interest rate risk. They reduce the security holder's principal risk by transferring interest rate risk to the issuer. This reallocation can benefit the issuer when the value of its assets is directly correlated with interest rate changes. As a result, banks and credit card companies are frequent issuers of FRNs.

The coupon rate of a typical FRN resets each period at a reference rate, often LIBOR (London Interbank Offer Rate), plus a fixed margin. The margin reflects default risk and other characteristics of the security, including any call or put options. The margin is greater (smaller) (1) the greater (smaller) the default risk or (2) the lower (higher) the maximum (minimum) coupon rate. A call option requires a greater margin, a put option a smaller margin.

Inverse FRNs

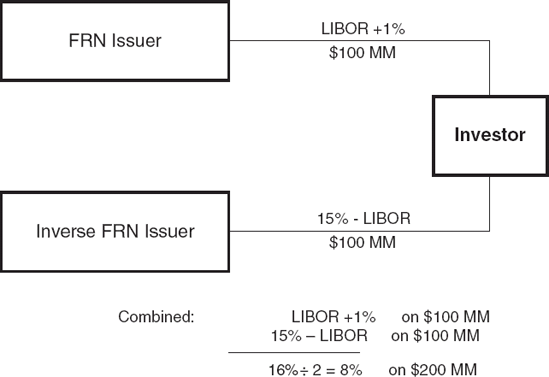

Inverse FRNs were introduced in 1986 (Ogden, 1987; Smith, 1988). Depending on the sponsoring investment banker, they are variously known as inverse floaters, reverse floaters, bull floaters, yield curve notes, or maximum rate notes. They have a coupon reset formula in which the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) is subtracted from a fixed percentage rate, such as 15% -LIBOR. As LIBOR increases (decreases), the coupon payment on an inverse FRN decreases (increases). Inverse FRNs are designed for hedging exposure to floating interest rates (or speculating on interest rate movement), because its payments offset those of the traditional FRN. Therefore, borrowing (or loaning) equal amounts of floating-rate and inverse floating-rate securities produces an approximately fixed rate.

Figure 7.5 illustrates how inverse FRNs can be used to hedge interest rate risk. Combining an inverse FRN paying 15% – LIBOR with an equal principal amount of an FRN paying LIBOR + 1% produces a synthetic fixed-rate note paying 8%.

Managing Price and Exchange Rate Risks

Commodity-linked bonds offer a hedge against volatile prices. The principal repayment and, in some cases, the coupon payments are tied to the price of a particular commodity, such as the price of oil or silver, or a specified commodity price index. A commodity producer's revenues tend to rise and fall with the commodity's price. Therefore, by having debt payments move with the commodity's price, the security reduces the volatility of the firm's (after-interest) cash flow. The security shifts the debt cost from times when the commodity producer is least able to pay to periods when it is most able to do so.

Dual-currency bonds, indexed-currency option notes, principal exchange rate–linked securities (PERLs), and reverse-principal exchange rate–linked securities (reverse PERLs) illustrate different forms of currency risk reallo-cation. They allow institutions wanting to deal in foreign currencies, but for regulatory or other reasons cannot, to purchase currency options.

Managing Business Risks

Alternative risk transfer (ART), also known as structured insurance, consists of a variety of techniques for transferring business risks that the traditional insurance market cannot handle cost effectively, or may not be able to handle at all. Fabozzi, Drake, and Polimeni (2008) describe these useful techniques, which include issuing insurance-linked notes (ILNs).

Catastrophe bonds are insurance-linked notes that are linked to a single peril. Other ILNs are multiperil bonds. Cat bonds reduce the interest or principal payments if the issuer suffers losses from a specified type of natural disaster, such as a hurricane or earthquake. For example, the Japanese owner of Tokyo Disneyland issued a $200 million cat bond in 1999 to insure against earthquake damage to the park. Cat bonds are issued by life and property and casualty insurers as an alternative to traditional reinsurance contracts. Investors bear a portion of the risk of loss from the specified natural disaster. Cat bonds are attractive for diversification purposes because natural catastrophic risks have very low correlations with financial risks. Therefore, the risk investors bear, and the interest rate they demand, is relatively low. Cat bonds have also been issued to cover difficult-to-insure risks. For example, the sponsors of the 2006 World Cup issued a $260 million cat bond to insure against a terror-related cancellation of the tournament.

If a firm can securitize an asset or a loan so that it becomes publicly traded, the greater liquidity lowers the required return. Examples of asset securitization include residential mortgage-backed securities, commercial mortgage-backed securities, credit card receivable–backed securities, and automobile loan–backed certificates. All are publicly registered securities with yields significantly lower than those on the underlying assets.

Global bonds are structuredtoqualify for simultaneous issuance and subsequent trading in the U.S., European, and Japanese bond markets. Global bonds have greater liquidity than single-market debt issues. Catastrophe bonds securitize reinsurance contracts, and are more liquid because they are tradable. They are a good example of the trend toward securitizing contracts to appeal to a broader class of investors, including those who are sensitive to liquidity risk.

The tobacco asset securitizations are another good example of how securitization can improve liquidity. In November 1998, four cigarette manufacturers reached a historic settlement of smoking-related litigation with 46 states and six other political jurisdictions. The settlement obligates the manufacturers to pay more than $200 billion over about 25 years. New York City sold $709 million worth of tobacco flexible amortization bonds (TFABs) in November 1999 to monetize part of its share in the settlement and obtain funds for its capital program. It used a senior/subordinated structure and reserve accounts to obtain a single-A rating for the senior bonds.

A new security can add value by reducing agency costs arising out of conflicts of interest among managers, stockholders, and bondholders. For example, debt claim dilution from a leveraged buyout (LBO) may increase shareholder value at the expense of bondholders. Interest rate reset notes address this problem by providing bondholders with protection against a drop in the issuer's credit standing. Similarly, credit-sensitive notes and floating-rate, rating-sensitive notes bear a coupon rate that varies inversely with the issuer's credit standing. All of these securities, however, have a potentially serious flaw. The interest rate adjustment mechanism will tend to increase the issuer's debt service burden just when it can least afford it—when its credit rating has fallen, presumably as a result of diminished operating cash flow.

Puttable bonds provide a series of put options that protect bondholders against deterioration in the issuer's credit standing. Others give the right to put the bonds back to the issuer if there is a change in corporate control or a leverage increase above a specified level. Such poison-put options protect bondholders against event risk.

Increasing-rate notes provide an incentive for the issuer to redeem the notes on schedule. They have been used as bridge financing and replaced by more permanent financing. Unfortunately, the increasing-rate feature can have a perverse effect. In the extreme, the increasing-rate feature can require such a large jump in the interest rate that the issuer is forced into bankruptcy.

A number of innovative debt securities increase stockholder value by reducing the underwriting commissions and other transaction costs associated with raising capital. Extendible notes, variable-coupon renewable notes, puttable bonds, and euronotes and euro-commercial paper do this with issuer or investor options to extend the maturity. For example, the early extendible notes typically included an interest rate adjustment every two or three years, which avoids the rolling-over refinancing expense. Refinements of this concept, such as certain puttable bonds and re-marketed reset notes, give the issuer greater flexibility in resetting the terms of the security.

The more recent generation of extendible notes is designed to qualify as investments for money market mutual funds. Money funds in the United States are restricted to securities with a maturity of 366 days or less. The notes pay interest monthly for added appeal to these funds. However, issuers would prefer longer maturities to reduce their refunding risk. Investors can elect to extend the maturity of the extendible notes by one month on each interest payment date. The notes provide that the coupon will step up periodically. This feature gives investors a strong incentive to exercise the extension option unless the firm's credit deteriorates.

Euronotes and euro-commercial paper extended commercial paper to the Euromarket. Commercial paper reduces transaction costs by allowing corporations to invest directly in one another's securities, without an intermediary.

Reducing Investor Transaction Costs

Innovative securities can reduce investor transaction costs to the extent they offer a lower-cost way of obtaining investor goals, such as diversification.

Securities that reduce the total amount of taxes paid by the firm and its investors can add value. Such tax arbitrage occurs when a firm issues debt to investors who have a marginal tax rate on interest income that is lower than the firm's marginal income tax rate. For example, premium bonds, with above-market interest rates, have been issued in exchange for outstanding high-coupon bonds to create a tax arbitrage (Finnerty, 2001). The exchange is essentially a refunding of high-coupon bonds that preserves debt-service parity. A taxable bondholder can amortize the premium (either new issue or market) over the remaining life of the bond, which conveys tax benefits. The issuer also benefits because the premium paid to retire the old debt is tax deductible.

Tax-Trading Strategies

Flexibility in recognizing capital gains and losses for tax purposes creates valuable tax-timing options. Evidence shows that the value of tax-timing options represented between 3.05% and 11.55% of the prices of bonds issued at close to par, between 1.42% and 4.93% of the prices of bonds issued at a moderate discount, and between 4.23% and 13.45% of the prices of zero-coupon bonds, depending on the investor's tax situation (Sims, 1992; Strnad, 1995). The tax rules for original issue discount (OID) bonds make the tax-timing options of deeper-discount bonds more valuable.

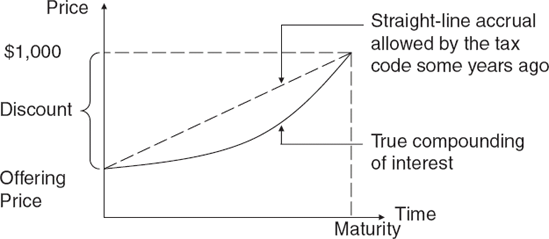

Figure 7.6 illustrates the tax arbitrage opportunity that existed at one time under the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. The firm was permitted to deduct interest faster than it compounded in the early years. It correspondingly deducted it more slowly in the later years. But the front-end loading of the interest deductions was beneficial because of the time value of money. There was no offsetting acceleration in income tax liability when the zero-coupon bonds were sold to pension funds.

Debt Maturity and the Tax-Deductibility of Interest

The Internal Revenue Code requires that a bond have a stated maturity date or else give bondholders the right to force redemption (that is, a put option) on a stated date in order for the issuer to deduct the interest payments for tax purposes. Some foreign jurisdictions allow tax-deductibility even for perpetual bonds. In 1995, after U.S. firms began issuing 50-year and 100-year bonds, so-called supermaturity bonds, the Treasury Department proposed eliminating the tax deduction for interest on greater-than-40-year bonds but it did not become law. The Treasury Department estimated that eliminating the tax deduction for interest on supermaturity bonds could raise a total of $6.5 billion over 7 years. Understandably, others predicted that firms would simply stop issuing supermaturity bonds. As predicted, with the proposed tax change in 1995, Monsanto Company immediately canceled its previously announced plans to issue $200 million face amount of 100-year bonds.

Bank regulations for debt instruments to qualify as primary capital have changed several times since the mid-1980s. Banks have responded predictably with new debt securities designed primarily to meet such regulations. Examples include equity contract notes, which subsequently convert into the common stock of the bank (or its holding company); equity commitment notes, which the issuer (or its parent) commits to refinance by issuing securities that qualify as capital; and sinking-fund debentures that pay sinking fund amounts in common stock rather than cash.

Variable-coupon renewable notes are a refinement of the extendible note concept discussed earlier. The maturity of the notes automatically extends 91 days at the end of each quarter—unless the holder elects to terminate the automatic extension, in which case the interest rate spread decreases. The reduction in spread can be avoided by selling the notes. These features were designed to meet investment regulations on money market mutual funds at the time.

Commodity-linked bonds allow institutions to speculate in commodity options, or invest in them as an inflation hedge, when regulatory or other reasons disallow them from purchasing commodity options directly. Similarly, bonds with interest or principal payments tied to a foreign exchange rate or denominated in a foreign currency allow institutions to speculate in foreign currencies, or invest in them as a hedge, when they cannot make such investments directly. Indexed-currency option notes and many other securities developed in the 1980s and 1990s that contain embedded commodity options or currency options of various forms were motivated by a desire to circumvent regulatory restrictions.

Covered bonds are debt instruments that are issued by European banks and that enjoy special regulatory treatment. They are overcollateralized by sound assets, such as residential mortgage loans or public sector bonds. They are issued under special legal provisions that insulate them from the issuing bank's default on its other debt even though the debt and the assets that collateralize them remain on the bank's balance sheet. Their bankruptcy remoteness enables them to qualify for a triple-A rating even though the bank's other debt is lower rated. Due to their high credit quality, bank regulators assign them a privileged credit risk weighting, and investment funds and insurance companies are allowed to invest a higher percentage of their assets in the covered bonds than in the other bonds of any single issuer. This favored legal and regulatory treatment has led to enormous growth in this asset class in Europe within the last few years.

Interest rate swaps, fixed-rate notes, and floating-rate notes can be structured to take advantage of specific future movements of interest rates (or a currency or commodity price), usually by including one or more interest rate options. These instruments are known as structured products (Crabbe and Argilagos, 1994; Brown and Smith, 1996). Generally, they are designed around an interest rate swap (and called a structured swap) or around a fixed-rate or floating-rate note (called a structured note). Prior to a recent change in the accounting for derivatives, structured swaps had often been preferred because it was easier to keep them off the balance sheet.

Market participants often have a "view" on the direction of interest rates, that is, they have an expectation about where interest rates are headed. But even when there is no explicit expectation and no intended bet on future interest rates, there is an implicit view in every decision to issue or invest in debt. Even a simple decision to invest in back-to-back three-month Treasury bills rather than buying six-month Treasury bills has an implicit view—in this case, that the three-month Treasury bill rate on the rollover date is likely to be above the rate the forward curve now predicts.

Structured products are distinguished, however, by the specificity of the view. The view can be tailored in any number of ways, such as a specific interest rate staying within a particular interest rate band, or the difference between specified short-term and long-term interest rates changing in a particular way. One can bet on the direction of interest rates, changes in the shape of the yield curve, shifts in interest rate volatilities, and so on.

As noted, inverse FRNs can be used for hedging. On the other side of the transaction, an investor who believes interest rates are going to fall can buy inverse FRNs. Their coupon rises while the required yield falls if interest rates decline. An investor can take a more aggressive view by investing in leveraged inverse FRNs, which is a refinement of the inverse FRN that provides even greater price sensitivity to interest rate changes.

Leveraged Inverse FRNs

Suppose an inverse FRN pays 15% – LIBOR, and LIBOR is currently 7%. A leveraged inverse FRN would typically pay 22% − 2 × LIBOR. The term "leveraged" refers to the multiple applied to LIBOR, in this case 2. The leveraged inverse FRN is more interest rate sensitive because its coupon changes twice as fast. The sensitivity can also be seen in the security's duration. The duration of an inverse FRN is roughly twice the duration of an identical-maturity par-value fixed-rate note. Similarly, the duration of a leveraged inverse FRN is more than twice the duration of a fixed-rate note of like maturity, and an even larger multiple creates an even longer duration.

Collared FRNs

Sometimes investors or issuers want protection against too much interest rate volatility. In such cases, they can purchase another contract that will provide a cap (maximum) or a floor (minimum) on the FRN's rate, or purchase an FRN that includes a cap or floor. A collared FRN is an FRN with both a cap and a floor attached. Early issuers of collared FRNs, like those of inverse FRNs, were able to reduce their cost of borrowing (after offsetting the effects of the embedded cap and floor), by offering investors a combination of securities that was cheaper than buying them individually.

Creating Synthetic Instruments through Financial Engineering

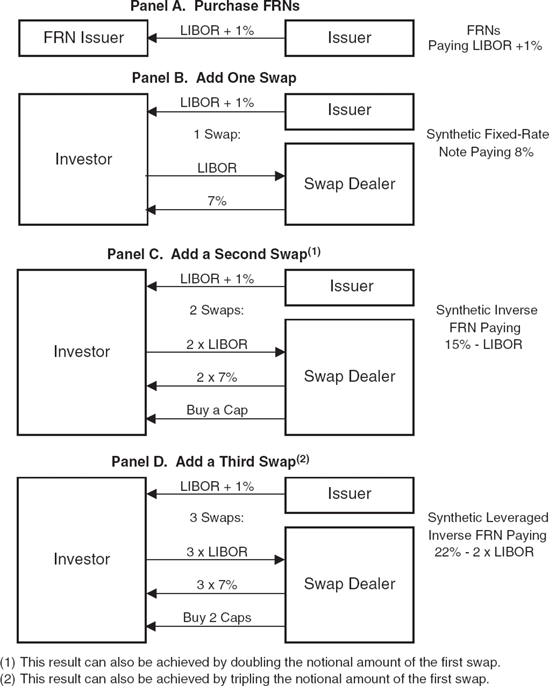

An inverse FRN, barring default, is equivalent to purchasing a fixed-rate note, going short a swap (to pay floating and receive fixed), and buying an interest rate cap. Figure 7.7 shows how layering additional short swaps on top of a long position in an FRN creates different synthetic (fixed-rate and floating-rate) debt instruments. In panel A, an investor purchases FRNs. In panel B, the investor then sells a swap (to receive 7% fixed and pay LIBOR). The swap's notional amount equals the principal amount of the FRNs. Combining the long position in the FRNs and the short position in the swap produces a synthetic fixed-rate note paying 8%.

In panel C, selling a second swap that is identical to the first (or doubling the notional amount of the first swap) transforms the synthetic fixed-rate note into a synthetic inverse FRN paying 15% – LIBOR. This synthetic instrument combines a long position in FRNs and two receive 7% pay–LIBOR swaps. In panel D, selling a third identical swap converts the synthetic inverse FRN into a synthetic leveraged inverse FRN.

Investors buy inverse FRNs, rather than creating synthetics, because it is simpler and has less credit risk. Issuers of inverse FRNs usually have strong credit, often AAA-rated. The synthetic involves bearing credit risk on the underlying FRN, on the two swaps, and on the cap. Also, some potential investors might be prohibited, by policy or regulation, from buying derivative contracts. Embedding the derivatives in a structured note, such as an inverse FRN, provides a way around such restrictions.

Other investors create synthetic inverse FRNs, rather than buying the security, because they might want to adjust or "unwind" their position. With the synthetic, investors can make adjustments at relatively low cost, and avoid the cost of selling and repurchasing the entire principal. This is another example of using a particular configuration to reduce transaction costs.

A credit-linked note (CLN) combines a plain vanilla bond and a credit default swap (Fabozzi, Davis, and Choudhry, 2006). The issuer of the CLN is the credit protection buyer, and the investor is the credit protection seller. If no credit event occurs during the life of the CLN, the investor receives a higher coupon rate. But if a credit event occurs, the coupon rate or the principal repayment decreases according to a formula that is tied to the loss resulting from the credit event. For example, banks that issue credit cards and sell unsecured bonds to fund these receivables have issued CLNs that reduce the principal repayment obligation to 85% of face if the credit card default rate exceeds 10%. The credit default swap embedded in the CLN pays 15% (100% −85%) of face when the 10% default rate credit event occurs, which transfers default risk from the bank to the CLN purchasers.

A popular debt (or debt-like) innovation that has gone through several stages of development is the hybrid capital security. Hybrid securities have a variety of different structures, and they seem to be continually evolving. But they all share certain general characteristics. Hybrids are fixed-income instruments that are accorded some degree of equity credit for the issuer by the rating agencies or are accepted as capital by the issuer's main regulator because they combine features of debt and equity.

They provide regular monthly or quarterly income at a stated rate (a percentage of liquidation value), the liquidity of a publicly traded instrument, and an investment-grade credit quality. Monthly distributions are designed to appeal to retail investors and money market funds. Like corporate debt securities, they generally rank senior to common and preferred stock in the issuer's capital structure, have a stated maturity, and the interim payments qualify as interest for corporate income tax purposes.

However, they also carry certain additional investor risks, including the risks of optional redemption, deferred payments, and extension. They rank junior to corporate unsecured debt. Payments cannot be made on junior subordinated debentures until all required payments have been made on the issuer's "senior" obligations and all other conditions in the indenture have been met.

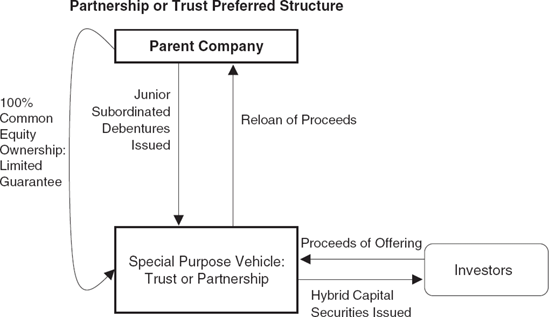

The first hybrid capital securities, trust preferred securities, were issued about 10 years ago. Figure 7.8 illustrates their basic structure. A firm sets up a special purpose entity (usually a trust but possibly a partnership) that issues the hybrid capital securities and invests the proceeds in an issue of the parent firm's junior subordinated debentures. Most hybrid capital securities have an initial maturity between 20 and 49 years and have a fixed-price call feature that is activated after 5 or 10 years. Some non-U.S. firms have issued perpetual hybrid capital securities. Although the monthly or quarterly payments are tax deductible, these hybrid capital securities are different from conventional bonds in that they allow deferral of distributions for up to five years. During the deferral period, income continues to accrue for income tax purposes, and the investor is liable for income tax on the deferred income, even though the investor does not receive any cash payments. (To avoid such a tax liability, the securities can be held in a tax-deferred retirement account.) At the end of the deferral period, the issuer must pay all deferred distributions in cash or else be in default. Like regular preferred stock, deferral requires suspension of all cash dividends (common and preferred). In some cases, the issuer also has the option to extend the maturity of the securities, although it cannot be used if payments are being deferred. Neither can the payment-deferral option be used to extend the maturity.

An offering of hybrid capital securities does not affect the parent firm's balance sheet to the same extent as an issue of conventional debt. Rating agencies seem to view hybrid capital securities as similar to preferred stock because they provide long-term capital that permits the issuer to defer payments in case of financial distress. They reflect a common theme in securities innovation, attempts to craft new securities that qualify as debt for income tax purpose but have equity-like features.

The newer hybrids are usually structured either as debt to allow the issuer to deduct the interest payments for income tax purposes or as preferred stock to allow investors who are C corporations to claim the dividends received deduction. Investors expect regular interest or dividend payments and, at least in the United States, the repayment of principal either at a scheduled maturity date or at a synthetic maturity date. Hybrids can be callable, some as early as the fifth anniversary. If there is a step-up in the interest rate on the call date or a conversion from a fixed to a floating interest rate after that date, the securities are typically priced on the assumption that the hybrids will be redeemed on the call date. The step-up or the conversion in interest rate creates a synthetic maturity because investors expect that the issuer will call the hybrid to avoid paying the increased coupon or having the interest rate float.

Hybrid security structures also typically have certain deferral features, either mandatory or optional, which may interrupt the payment stream. The deferral feature, along with other features that may affect scheduled payments, are reviewed by the rating agencies in determining the amount of equity credit to be given the security. Mandatory deferral typically occurs only if the issuer is in significant financial distress. Optional deferral features are not typically utilized by issuers. Often, these securities are issued by investment-grade or highly rated financial institutions. Such issuers are highly unlikely to defer because they need continuous access to the capital markets. Even one deferral would send a signal to the market that the issuer is experiencing financial distress, which would significantly discourage lenders from committing more capital. Even one deferral can prevent the issuer from paying cash dividends, which will in turn prevent it from issuing equity securities to raise capital, at least until the deferral is eliminated. Lastly, issuers are very reluctant to defer payments on hybrids in the form of preferred stock because the terms of such securities often grant affected security holders the right to elect one or more directors in the event that payments have been deferred for a specified period of time. Thus, hybrid investors can be reasonably assured of receiving a steady stream of payments. As a consequence, hybrid securities are particularly attractive to life insurance companies and other investors who desire the combination of high yield and low default risk (Kumar and Shah, 2006).

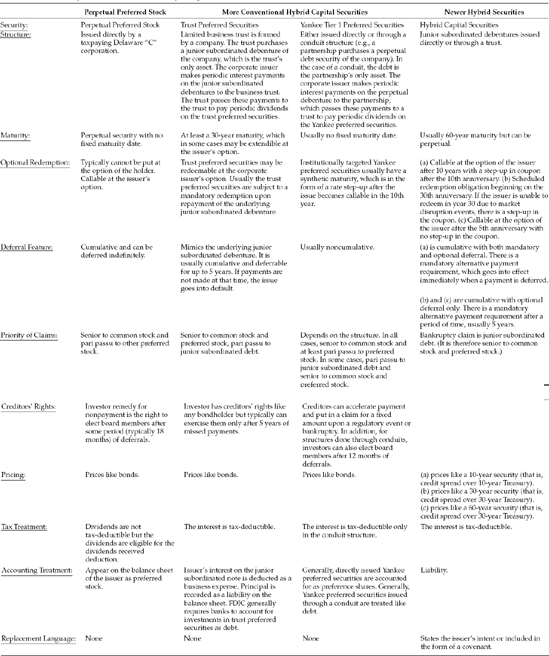

Newer hybrids differ in some key respects from conventional preferred stock and also from traditional trust preferred hybrids. Table 7.2 summarizes the typical features of four types of hybrid securities that can qualify as capital for bank regulatory purposes: conventional perpetual preferred stock, trust preferred securities, Yankee tier 1 preferred securities, and the newer hybrid capital securities of the type involved in the National Association of Insurance Commissioner's reclassification of hybrid capital securities in 2007. Perpetual preferred stock, a traditional hybrid security, has no fixed maturity, although the security is redeemable at the issuer's option. Dividends are not tax deductible, but they are eligible for the dividends-received deduction when the recipient is a C corporation. The lack of tax deductibility generally makes perpetual preferred stock less attractive to a fully taxable issuer than other hybrids that achieve tax deductibility.

Trust preferred stock and Yankee tier 1 preferred securities have both existed for at least ten years. They are long-dated preferred stock, which can be structured to achieve income tax deductibility for the interest payments when the company issues debt to a conduit that then issues the preferred stock to investors. Yankee tier 1 preferred securities are generally given more equity credit than trust preferreds by the rating agencies as they do not have a maturity date and their dividends are noncumulative.

Newer hybrid capital securities are generally structured as junior subordinated debentures. They are typically investment-grade or highly rated companies and so the opportunity to raise additional capital in a tax-efficient manner while obtaining relatively favorable rating agency treatment is attractive. The usual maturity of newer hybrid securities is 30 or 60 years, although some are perpetual. Some issues have a synthetic maturity as short as 10 years. Typically, the issuer either states its intention or else commits through a covenant to redeem the issue with proceeds from the sale of junior or pari passu securities if the hybrid issue is called, which is referred to as a "replacement" provision. Payment deferrals are cumulative, and some structures require mandatory deferral if certain balance sheet, income statement, or risk-based capital tests are met. Some of these securities have a mandatory alternative payment requirement, which starts immediately in some structures and within five years (20 quarters) in others. This feature requires the issuer to sell junior or pari passu securities in an amount sufficient to pay interest after payments have been deferred for a certain period of time. Failure to make the stipulated payment is an event of default.

Several firms have issued hybrid capital securities and used the funds to retire a portion of their preferred stock. Others have issued junior subordinated debt or conventional debt to replace preferred stock, in some cases offering preferred stockholders the opportunity to exchange their shares for the new debt.

Substituting debt for preferred stock generally elicits a favorable stock market reaction (see Masulis, 1980, 1983). There is both a favorable signaling effect, because interest is a fixed obligation and preferred stock dividends are not, and a favorable tax effect due to the tax-deductibility of interest. However, because of the five-year interest-deferral feature, the signaling effect of issuing hybrid capital securities is less favorable than issuing straight debt, although still positive.

For example, in June 1995, McDonald's Corporation offered to exchange up to $450 million aggregate principal amount of its 8.35% subordinated deferrable interest debentures due 2025 for up to 18 million shares of its 7.72% cumulative preferred stock. The debentures were offered in minimum denominations of $25 and make quarterly payments to match the preferred shares. The debentures allow McDonald's to defer interest payments for up to 20 consecutive quarters; mature in a lump sum; and, like the preferred stock, are redeemable at par beginning in December 1997.

The exchange offer met with only limited success; 26% of the preferred stockholders exchanged their shares. The lower-than-expected response rate was attributed to the higher-than-expected percentage of corporate holders, who could claim the 70% dividends-received deduction, which would be lost with the debt. In general, a debt-for-preferred exchange would not be profitable if the interest rate had to compensate preferred stockholders fully for the loss of the dividends-received deduction.

U.S. corporations are permitted to deduct from their taxable income 70% of the common and preferred stock dividends they receive from unaffiliated corporations. As a result, the receiving corporation's tax rate on dividend income is effectively 10.5% (30% of the 35% statutory federal corporate tax rate). This offers corporations an incentive to purchase preferred stock rather than commercial paper or other short-term debt instruments, the interest of which is fully taxable. Preferred stock provides a tax arbitrage under current tax law when nontaxable firms issue it to fully taxable corporations. Nontaxable corporate issuers find preferred stock cheaper than debt because corporate investors are willing to pass back part of the value of the tax arbitrage by accepting a lower dividend rate.

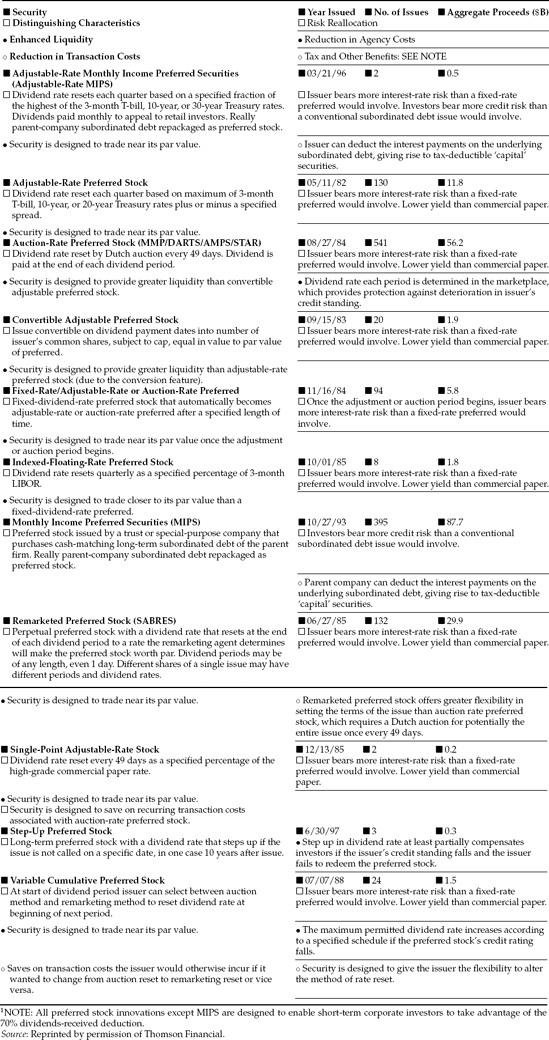

Purchasers of long-term, fixed-dividend-rate preferred stock are exposed to interest rate risk, and an interest rate increase could lower the value of the preferred stock by more than the tax saving. A variety of preferred stock instruments (see Table 7.3) have been designed to deal with this problem.

Adjustable-rate preferred stock was designed to reduce interest rate risk by adjusting the dividend rate by a formula specifying a fixed spread over Treasuries. At times, however, the spread investors have required to value the securities at par has differed significantly from the fixed spread specified in the formulas, causing the value of the security to deviate significantly from its face amount.

Convertible adjustable preferred stock (CAPS) was designed to eliminate this deficiency by making the security convertible on each dividend payment date into enough shares to make the security worth par. But although CAPS have traded closer to par than adjustable-rate preferred stocks, there have been only 13 CAPS issues. This may reflect the convertibility risk, which could force the issuer to issue common stock or raise considerable cash on short notice.

Auction-rate preferred stock carried the evolutionary process a step further. The dividend rate is reset by Dutch auction every 49 days, which represents just enough weeks to meet the 46-day holding period required to qualify for the 70% dividends-received deduction. A Dutch auction accepts the highest bid, the next highest bid, and so on, until a market-clearing price is found for which all the securities offered for sale will be purchased. All the sales then take place at the market-clearing price. Auction-rate preferred stock has a variety of names (MMP, money market preferred; AMPS, auction market preferred stock; DARTS, Dutch auction rate transferable securities; and STAR, short-term auction rate, among others), depending on the securities firm offering the product.

There have been two attempts to refine the adjustable-rate preferred stock concept further, but only one was successful. Single-point adjustable-rate stock (SPARS) has a dividend rate that adjusts automatically every 49 days to a specified percentage of the 60-day high-grade commercial paper rate. The security is designed to provide the same liquidity as auction-rate preferred stock, but with lower transaction costs since no auction need be held. The problem with SPARS, however, is that the fixed-dividend-rate formula introduces a potential agency cost. Because the dividend formula is fixed, investors will suffer a loss if the issuer's credit standing falls. Primarily for this reason, there have been only two SPARS issues.

Remarketed preferred stock, by contrast, pays a dividend that is reset at the end of each dividend period to a dividend rate that a specified remarketing agent determines will make the preferred stock worth par. Such issues permit the issuer considerable flexibility in selecting the length of the dividend period (it can be as short as one day). Remarketed preferred also offers greater flexibility in selecting the other terms of the issue. In fact, each share of an issue could have a different maturity, dividend rate, or other terms, provided the issuer and holders so agree. Remarketed preferred has not proven as popular with market participants as auction-rate preferred stock. Through July 2007, more than nine times as much auction-rate preferred stock as remarketed preferred stock has been issued.

Variable cumulative preferred stock was born out of the controversy over whether auction-rate preferred stock or remarketed preferred stock results in more equitable pricing. It effectively allows the issuer to decide at the beginning of each dividend period which of the two reset methods will determine the dividend rate at the beginning of the next dividend period.

Monthly income preferred securities make monthly dividend distributions, whereas most fixed-rate preferred stock pays dividends quarterly. Monthly dividends appeal to retail investors and other investors looking for a more regular flow of cash from their investments.

In view of the similar structures for debt and preferred stock, a variety of preferred stock instruments are understandably adaptations of debt innovations. One of the more interesting examples of this is gold-denominated preferred stock. Commodity-linked preferred stock is like commodity-linked bonds. Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Inc. raised $233 million in 1993 by issuing gold-denominated preferred stock. The issue price, quarterly dividend, and redemption value at maturity are each tied to the price of gold. Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold used the issue proceeds to help fund the expansion of one of the world's largest gold mines, its Grasberg mine in Irian, Jaya, Indonesia.

Several mutual funds that were unable to own physical gold were among the investors in the new issue, which embodied a 10-year forward contract on gold. The investors purchased the shares for $38.77 each. At maturity, each investor will receive the value of 1/10 of an ounce of gold for each share, whether the price of gold is higher or lower than $387 per ounce. In effect, the investor will trade the stated value of $38.77 per share at maturity for the cash value of 1/10 of an ounce of gold, profiting if the price of gold is above $387 per ounce and losing if it is below.

Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold designed the issue as a forward sale of 600,000 ounces of gold, hedging some of its gold price risk exposure. It chose to issue preferred stock rather than arrange a more traditional gold loan because it wanted a longer-dated security that did not require any amortization of principal and did not have the restrictive loan covenants usually found in gold loans.

Securities innovation has resulted in several new convertible securities, some of which have been very successful, such as mandatory convertible preferred stock, puttable convertible bonds, and zero-coupon convertible debt. These have been popular in large measure because of financial contracting considerations. For example, convertible bonds reduce agency costs arising from possible conflicts of interest between stockholders and other security holders, such as the problems of asset substitution, underinvestment, and claim dilution. Table 7.4 describes several of the innovations in convertible securities.

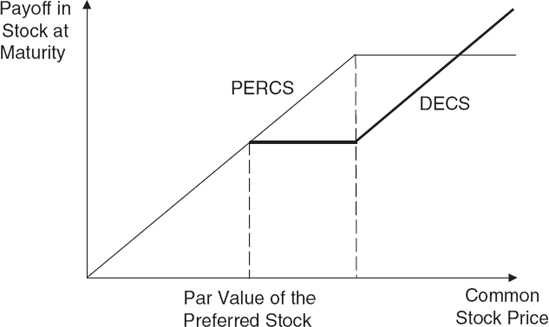

Preferred equity redemption cumulative stock (PERCS) is a form of mandatory convertible preferred stock. Its conversion feature differs from a traditional convertible preferred stock because conversion into common stock is not an American option held by the security holder. In fact, it is not an option at all. At maturity, as the name implies, conversion is mandatory. Furthermore, the issuing firm holds a call option, allowing it to redeem the security for cash prior to maturity, even if the value of the common stock exceeds the redemption price. Therefore, referring to this as a convertible security is somewhat of a misnomer. The contract is in fact more like a futures contract for common stock from the security holder's viewpoint. The holder has essentially purchased the common stock to be delivered at a future date and sold an option to the firm for it to instead pay cash prior the delivery date.

PERCS pay a higher dividend rate than the underlying common stock. However, the firm's call option puts a cap on the payoff. PERCS alter the investor's return distribution, providing greater dividend income in exchange for a cap on capital appreciation. In response to some investor-voiced objections to the cap, securities dealers created dividend-enhanced convertible stock (DECS) and preferred redeemable increased dividend equity securities (PRIDES), which are similar. Conversion of DECS is also mandatory, but the conversion feature is initially out-of-the-money and the payoff is not capped. Through year-end 2000, the PERCS-type and DECS-type convertible preferred had been issued in nearly equal amounts.

Figure 7.9 compares the payoff patterns for PERCS and DECS. The investors' returns are capped with PERCS. They are not with DECS, which eliminates the initial upside in the underlying common stock but provides full appreciation thereafter.

Many of the convertible security innovations have a tax motive. Convertible-exchangeable preferred stock is attractive to firms that are not currently paying income taxes but may in the future. It starts out as convertible perpetual preferred stock, but the issuer has the option to exchange for convertible subordinated debt with the same conversion terms and an interest rate equivalent to the original dividend rate. The exchange feature enables the issuer to replace the convertible preferred stock dividends with tax-deductible convertible debt interest payments when the firm begins paying income taxes. Not surprisingly, a large volume of such securities have been issued by firms that were not currently paying federal income taxes.

Contingent convertible bonds are a variant of the basic puttable convertible bond structure plus an added tax and accounting benefit for the issuer. Bond interest payments are contingent on some specified factor, such as the dividend rate on the underlying common stock. Until 2005, provided this contingency was neither remote nor incidental, the contingent interest rules under the Internal Revenue Code allowed the firm to take interest deductions based on the much higher interest rate on its straight debt with like maturity, payment dates, and seniority. In addition, conversion was often contingent on the stock price rising above a specified threshold, such as 30% above the share price at the issue date. This feature allowed the firm to keep the underlying shares out of the fully diluted earnings per share calculation until the share price reached the threshold. The accounting rules were changed in 2005 to treat contingent convertibles just like regular convertibles. Firms began issuing contingent convertible bonds in November 2000. More than $125 billion worth were issued before the accounting and tax rules were changed in 2005.

Adjustable-rate convertible debt was a very thinly disguised attempt to package equity as debt. The coupon rate varied directly with the dividend rate on the underlying common stock, and there was no conversion premium (at the time the debt was issued). After just three issues, the IRS ruled that the security is equity for tax purposes, thereby denying the interest deductions. Not surprisingly, the security has not been issued since that ruling.

Zero-coupon convertible debt, which includes liquid yield option notes (LYONs) and ABC securities, represents a variation on the same theme. If the issue is converted, both interest and principal are converted to common equity, in which case the issuer will have effectively sold common equity with a tax-deductibility feature. Zero-coupon convertible debt has been very popular among individual investors who have purchased it for their individual retirement accounts. These securities often contain put options that guarantee a minimum holding-period return and reduce agency costs.

Debt and warrants (exercisable into the issuer's common stock) can be combined to create synthetic convertible debt, with features that mirror those of conventional convertible debt (Finnerty, 1986). Synthetic convertible debt has a tax advantage over a comparable convertible debt issue because, in effect, the warrant proceeds are deductible for tax purposes over the life of the debt issue.

Puttable convertible bonds reduce agency costs by protecting investors against deterioration in the issuing firm's credit standing by giving them the option to put the bonds back to the issuer. The investors can exercise their put option if credit quality deteriorates or exercise their conversion (call option) if the firm's share price appreciates sufficiently. Conversion price reset notes adjust the conversion price downward on one or more specified dates if the market value of the underlying common stock is below the conversion price. This reset feature at least partially protects investors if the firm's managers take actions that diminish the firm's value. Similarly, convertible interest rate reset debentures adjust the interest rate upward if the issuing firm's credit standing deteriorates.

Contingent convertible bonds provide downside protection for investors in exchange for reduced periodic cash payments. They are issued at par initially with a zero yield to maturity. Contingent interest becomes payable if the conversion option becomes deep in-the-money. However, investor have a series of put options, exercisable at par, usually beginning as early as one year after the bonds are issued. Contingent convertible bonds differ from traditional convertible bonds in that a strip of in-the-money put options plus a stream of contingent interest payments replace the stream of stated interest payments.

Cash-redeemable LYONs and cash-settled convertible notes pay the value of the underlying common stock in cash, in lieu of conversion. Many investors, such as convertible bond mutual funds, sell the common stock following conversion as soon as they can do it on an orderly basis. For them, cash settlement reduces transaction costs. The security is less attractive to hedge funds because they do not receive conversion shares, but instead have to buy common shares in the open market, to cover their short positions.

Banks have issued capital notes because they can be substituted for equity (subject to certain restrictions) for regulatory purposes, but the interest payments are tax deductible. For example, prior to the passage of the Financial Institutions Reform Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA), banks issued equity contract notes. They consisted of interest-deductible debt with a mandatory common stock purchase contract. They qualified as primary capital for bank regulatory purposes because conversion was mandatory.

One of the innovative securities described earlier, PERCS, was created to help a corporation deal with the otherwise disruptive effects of reducing its dividend payout. The firm had concluded that it had to reduce its dividend per share. At the same time it announced a reduction of its dividend payout, the firm offered stockholders the opportunity to exchange their shares for PERCS, which its investment bankers had designed specifically for that purpose. Since that initial issue, PERCS have been issued in cash transactions presumably as an alternative to a traditional issue of convertible preferred stock.

The impact of dividend policy on firm value has been extensively examined, especially since Miller and Modigliani's (1961) demonstration of its irrelevance in a perfect capital market environment. Three broad categories of imperfections can cause dividend policy to affect firm value: asymmetric information, asymmetric taxes, and transactions costs. Among these, asymmetric information—specifically the information contentofadiv-idend announcement—is generally believed to have the potential for causing the largest impact on a firm's market value. This is because the so-called clientele effect may be able to mitigate much of the impact of asymmetric taxes and transaction costs.

In equilibrium, investors sort themselves into various clienteles that invest in firms that follow the dividend policy that is most favorable to the clientele in terms of taxes and transaction costs. Of course, when a firm changes its dividend policy, investors in that clientele may be forced to incur transaction costs and tax liabilities as they sell their stock in that firm and purchase new shares in firms that have the dividend policy that is best for them.

Corporate dividend policies are notoriously stable, reflecting management's well-known reluctance to cut the dividend. But what can a firm do if it believes that cutting its cash dividend payout is a shareholder-wealth-maximizing decision? How can a firm communicate such a belief most accurately and at the lowest cost? If the dividend cut is perceived negatively, current shareholders would suffer a loss of wealth if they sell shares for less than their true value during the time it takes the market to see that the dividend cut is not negative after all.

Combining a PERCS-for-common exchange offer with a dividend cut can reduce the disruptive effects of a dividend cut for the following reasons (Emery and Finnerty, 1995):

It sends a credible positive signal to market participants about the firm's longer-run prospects.

It offers the option of continued capital gains tax deferral to shareholders who might otherwise sell their common shares and trigger a tax liability.

It offers the option of lower transaction costs to shareholders who choose to maintain their cash dividend income by exchanging for the PERCS rather than selling their common shares and reinvesting in higher-dividend-paying shares of other firms.

Five of the common equity innovations listed in Table 7.5 serve to reallocate risk: the Americus Trust, SuperShares, unbundled stock units, callable common stock, and put-table common stock.

The first Americus trust was offered to owners of AT&T common stock on October 25, 1983. It offered AT&T common stockholders the opportunity to retain their predivestiture shares because AT&T was ordered to divest its regional and local operating companies, which it did by distributing the shares of these companies to its shareholders. The Americus trust received this share distribution. More than two dozen other Americus trusts were later formed. An Americus trust offered the common stockholders of a firm the opportunity to strip each of their common shares into a PRIME component, which carried full dividend and voting rights and limited capital appreciation rights, and a SCORE component, which carried full capital appreciation rights above a threshold price. PRIMEs and SCOREs appeared to expand the range of securities available, thus helping make the capital markets more complete. Unfortunately, a change in tax law made the separation of a share of common stock into a PRIME and a SCORE a taxable event, and no new Americus trusts have been formed since that change (see Francis and Bali, 2000, for more on the saga of PRIMEs and SCOREs).

SuperShares were an attempted extension of PRIMEs and SCOREs. They would have divided the stream of annual total returns on the S&P 500 portfolio into two components that are similar to the two components created by the Americus trust: (1) Priority SuperShares that paid the dividends on the S&P 500 stocks and provided limited capital appreciation and (2) Appreciation SuperShares that provided capital appreciation above the Priority SuperShares' capital appreciation ceiling. The new securities were to be issued by a trust that was to contain a portfolio of common stocks that mirrored the performance of the S&P 500 Index and a portfolio of Treasury bills. The trust also would issue two other classes of securities, one of which (Protection SuperShares) would have functioned like portfolio insurance. Unfortunately, a variety of problems arose and no SuperShares were ever issued.

Unbundled stock units (USUs) also can be thought of as an extension of PRIMEs and SCOREs (Francis and Bali, 2000). They divide the stream of annual total returns on a share of common stock into three components: (1) a 30-year "base yield" bond that would pay interest at a rate equal to the dividend rate on the issuer's common stock (thereby recharacterizing the "base" dividend stream into an interest stream), (2) a preferred share that would pay dividends equal to the excess, if any, of the dividend rate on the issuer's common stock above the "base" dividend rate, and (3) a 30-year warrant that would pay the excess, if any, of the issuer's share price 30 years hence above the redemption value of the base yield bond. Despite extensive marketing efforts, the USU concept failed to gain wide investor support and encountered regulatory obstacles that led to its withdrawal from the marketplace before a single issue could be completed (Finnerty, 1992). Like the Americus trust and SuperShares, USUs were designed to give shareholders more flexibility in choosing among the different components of the total returns from holding common stock; each of these new forms would effectively allow shareholders to tailor the corporation's dividend policy to suit their own preferences.

Callable common stock consists of common stock, typically issued by a subsidiary company, coupled with a call option to repurchase the stock, typically held by the parent company. The call price steps up periodically. The parent company may be required to exercise all the outstanding purchase options if any are exercised. The common stock has capital appreciation potential, however, it is limited by the company's call option.

Puttable common stock consists of common stock coupled with an investor-held put option. This package of securities is comparable to a convertible bond (Chen and Kensinger, 1988). The put option reduces the information "asymmetry" associated with a new share issue by putting a floor under the stock's value. Puttable common stock issues often provide a schedule of increasing put prices in order to ensure a minimum positive holding period rate of return. Essentially, this security offers the downside protection of the put option, often in exchange for not getting the dividends that are paid to other shareholders. The put option may be especially valuable for initial public offerings (IPOs), where investor uncertainty is particularly great (and as a result, IPOs are typically underpriced).

Publicly traded limited partnerships, often referred to as master limited partnerships (MLPs), became popular in the United States in the 1980s. They avoided double taxation of firm income, just like any other partnership, but their units could be traded publicly, just like the common stock of a corporation. The Revenue Act of 1987 eliminated the tax advantage of most MLPs (other than MLPs engaged in the natural resource extraction and oil and gas pipeline industries) by making them taxable as corporations if their units are publicly traded.

Financial engineering involves the design of innovative securities, which provide superior, previously unavailable risk/return combinations. This process often includes coupling new derivative products with traditional securities to manage risks more cost effectively. The key to developing better risk-management vehicles is to design financial instruments that either provide new and more desirable risk-return combinations or furnish the desired future cash-flow profile at lower cost than existing instruments.