FRANK J. JONES, PhD

Professor, Accounting and Finance Department, San Jose State University and Chairman of the Investment Committee, Salient Wealth Management, LLC

Abstract: Insurance and investments are distinct concepts. This distinction leads to the development of various insurance and investment products. In practice, however, there is an overlap between some types of insurance products and investment products. This overlap occurs due partially to specific tax advantages provided to investment-oriented life insurance products. The two major types of investment-oriented life insurance are cash value life insurance and annuities.

Keywords: Pure insurance, investment-oriented insurance, cash value life insurance, whole life, variable life, universal life, variable universal life, annuities, variable annuities, fixed annuities, guaranteed investment contract (GIC), participating policies, general account products, separate account products, immediate annuity, deferred annuity, credited rate, flexible-premium deferred annuity (FPDA), single-premium deferred annuity (SPDA)

This chapter begins with an overview of insurance. The remainder of the chapter considers the major types of investment-oriented life insurance, mainly cash value life insurance and annuities.

Insurance is defined as a contract whereby one party—the insured—substitutes a small certain cost (the insurance premium) for a large uncertain financial loss based on a future contingent event. Thus, there are two parties to an insurance contract, the insured, who pays the premium and receives protection; and the insurer (or insurance company), which collects the premium and provides the protection.

Most types of insurance provide for a prespecified payment from the insurer to the insured if and when the contingent insured event occurs and otherwise have no value. This is called pure insurance. Other types of insurance have a "cash value" even if the contingent event does not occur. This is called investment-oriented insurance. The two types of investment-oriented insurance are discussed later.

The major types of insurance, in general, are:

Life

Health

Disability

Property (home and automobile)

Liability

Other types of insurance include long-term care, business interruption, and workers' compensation.

Of these types, only life insurance has a cash value form in addition to pure insurance. Cash value life insurance is a very important type of investment-oriented life insurance. Therefore, let's consider life insurance in more detail.

According to a pure life insurance contract, the insurer (the life insurance company) pays the beneficiary of the contract a fixed amount if the insured dies while the life insurance contract is valid. If the insured does not die while the policy is valid, the insurance contract becomes worthless at its expiration. To provide pure life insurance contracts, the insurance company—specifically its actuaries—calculate the probability of the insured dying during the period the contract is valid. Many variables affect this probability, including physical health, whether the person smokes, and gender. The most important variable, however, is the insured's age. Specifically, the probability of death increases with age. Actuaries estimate this relationship with some degree of precision.

Obviously the insurance premium charged by the insurance company must cover the average amount paid to all insureds, the administrative and distribution costs, and a profit. The cost of pure insurance to the company depends on the probability of the insured dying during the period which increases with age.

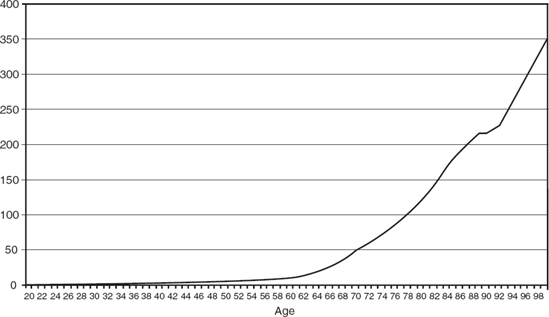

Overall, the premium charged to the insured for a pure life insurance contract is shown in Figure 62.1, which is determined by the probability of death (the "cost" of paying the death benefit) plus the distribution and administrative costs plus the profits. Pure life insurance is called term insurance. It is applicable over the term of the policy.

There are three types of term insurance. The most common type is called annual renewable term. According to this type, the insured has the right to renew the coverage every year without new underwriting (that is, without a new medical examination). Premiums, however, change; that is, they increase each year and become very expensive at older ages, as indicated below. A second type of term insurance, much less common, does not have the guaranteed renewability feature of the above.

The third type of term insurance is level-premium term, wherein the premium is constant during the life of the policy. Its level is higher than for annual renewable term early in the policy. However, the premium does not increase with age and is lower than an annual renewable term policy late in the life of the policy. Typically, policies of ten years or more are written on a level-premium term.

For annual renewable term the annual premium increases significantly with age. Traditional whole life policy premiums are much higher than for term insurance, often ten times higher or more.

The costs of non-life types of pure insurance are determined in a similar manner. However, in other types of insurance, factors other than the age of the insured may be the dominant variables. For example, location may be important in home insurance: It costs more to insure against hurricanes in Miami and Galveston than in Chicago and San Francisco. And it costs more for a young male (age is a also a factor here) than a middle-aged female to buy automobile insurance. For both, however, prior driving record is important.

Consider some conceptual issues regarding risk management from the perspective of the insured and the willingness to provide risk coverage from the perspective of the insurer.

From the perspective of the insured, insurance is a mechanism for managing risk. Individuals experience many types of risk and the manner in which they manage the risk depends on the characteristics of the risk. Two important characteristics of the risk are the severity of the risk (the cost) and the frequency of the risk.

There are, in general, also four different ways to manage the risk. Consider specifically these four ways in the context of managing the risk of fire for a house.

Avoidance: Avoid the risk-producing activity. For example, do not build a house in a hot, dry area.

Reduction: Reduce the risk of an activity. For example, build a house in a hot, dry area, but add a sprinkler system.

Retain: Continue the risk-producing activity, but do not insure the risk, that is, self-insure. For example, build a house in a hot, dry area; do not buy insurance; and be prepared to pay for the house yourself if the house burns.

Insure: Engage in an insurance contract on the risk and pay the premium thereon. For example, buy fire insurance on your house. Fire insurance on a house in a hot, dry area will, however, be expensive.

The way in which an individual manages risk will depend on the characteristics of the risk, as summarized in Table 62.1. That is, insurance is most appropriate when the frequency of the insured event is low and the severity is high. Examples of this type of risk might be a serious automobile accident, your house burning down, or the death of a young person. From the perspective of the insurer, the diversification of the risk is important. The essence of insurance is that the financial burden of the losses suffered by a few is shared among many. Suppose it is estimated that in one year, 100 out of 100,000 homeowners will experience losses caused by fire. This is determined based on data assembled about what happened in the past. Instead of those 100 homeowners bearing the entire financial burden of the losses, the burden is shared among the 100,000 homeowners through premiums for homeowners' insurance, which includes protection against fire losses. It is necessary to be able to estimate in advance with reasonable accuracy the aggregate losses that will be suffered by the 100,000 homeowners.

The statistical concept of the "law of large numbers" is relevant. Considering again life insurance, assume that the probability of death during a 12-month period is 20% for a given age. If only one person of this age is insured, either 0% or 100% of the insureds die, and the insurer experiences either a large loss or a small gain (the premium). But if the insurer insures 100 people of this age at an actuarially determined premium, the insurer is likely to have a profit close to the average profit actuarially expected. The law of large numbers says there is more statistical certainty when a large number of insureds (which are diversified) are involved.

Table 62.1. Treatment of Risk by Type of Risk

Frequency | ||

|---|---|---|

Severity | High | Low |

| [a] | ||

| [b] | ||

| [c] | ||

High[a] | Avoidance or reduction (Insurance is very expensive)[b] | Insurance |

Low[c] | Retention or reduction | Retention |

[a] When the severity o f loss is high, retention is not realistic- another technique is needed. [b] When the frequency of loss is high and the severity is high, insurance is very expensive. [c] When the severity of the loss is low, insurance is not needed. | ||

Table 62.2. Investment-Oriented Insurance Product

|

The correlation or independence of the individual events is also important. For example, providing hurricane insurance to 100 houses in Galveston, Texas, does not benefit from the law of large numbers—either all or none of the houses are likely to experience a hurricane.

In the calculation of premiums, insurers estimate the future based on the past. Insurers need to feel comfortable that their estimates will apply to the future. To calculate the loss component of insurance premiums, insurers multiply their estimates of the probability of future losses times the dollar value of the loss.

This chapter does not consider any of the pure insurance products. Rather, it considers only various types of investment-oriented life insurance products. Such products are shown in Table 62.2. Each product is discussed in more detail in this chapter.

There is an important distinction in investment-oriented life insurance with respect to whether the insured or the insurance company bears the investment risk, that is, who gains or loses if the investment experience is greater or less than expected. Table 62.3 segregates the products by who bears the investment risk.

The products in the first column are called "general account products" and those in the second column are called "separate account products." The nature of this distinction is discussed later in this chapter.

In all types of pure insurance, the insurer, that is the insurance company, bears the risk of honoring the contract. That is, it is the obligation of the insurer to deliver the exact amount specified in the insurance contracts. But either the insurance company or the insured may bear the risk of underperforming.

Table 62.3. Types of Investment-Oriented Insurance by Risk Bearer

General Account (Insurer Risk) | Separate Account (Insured Risk) |

|---|---|

Whole Life Insurance | Variable Life Insurance |

Universal Life Insurance | |

GICs | Variable Annuities |

Fixed Annuities |

Cash Value Life Insurance

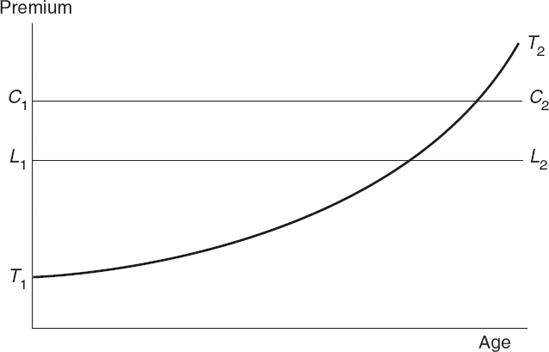

Consider how cash value life insurance relates to the discussion based on Figure 62.1 for pure life insurance. The premium for an annual pure life insurance (term insurance) contract is paid each year for a contract that expires after one year and is shown in Figure 62.1 which is reproduced in Figure 62.2. The annual term insurance premium is denoted by T1T2.

This premium, T1T2, has two important characteristics:

The premium increases each year for a new one-year contract, and increasingly so as age increases.

If the insured does not die during the year, the insurance contract expires worthless at the end of the year (and can be replaced by paying a higher premium the next year).

This consideration provides a transition to cash value life insurance. Suppose the insurance company provided pure life insurance for a period much longer than a year, for example the insured's entire life, but charged a constant, called level, premium. In fact, level premium term life insurance is available. In this case, the level premium represents the average premium over the term of the policy. Let L1L2 be the level premium of the term life insurance. Such a policy has no cash value.

Second, suppose that the initial (and constant) premium paid is higher than the cost of pure life insurance. This excess premium can be invested and build up cash value during the term of the policy. For example, in Figure 62.2 T1/T2 represents the initial cost of annual term insurance, L1/L2 the cost of level premium term insurance, and C1/C2 the level premium of cash value insurance. The excess amount of premium for cash value insurance over annual term, C1 – T1 at a young age, in addition to potentially covering the deficit between the cost of pure insurance and cash value insurance at an older age (e.g., T2 – C2), can be entered into an investment account of the insured. This is the essence of cash value life insurance.

Each year's premium is segregated into two components by the insurance company. The first is the amount needed to pay for the pure insurance, which, as indicated, increases each year. The second goes into the insured's investment account, which is the cash value of the life insurance contract. An investment return is earned on this cash value, which further increases the cash value. The buildup of this cash value and the ability to borrow against it both have tax advantages, as discussed below. Two important observations can be made here.

First, a common marketing or sales advantage attributed to cash value life insurance is that the higher premium paid will "force" the individuals to save, whereas if they did not pay the higher insurance premium, they would use their income for consumption rather than savings. According to this rationale, the higher insurance premium is, thus, forced savings.

Whether or not this first observation has merit, the second observation unequivocally does. The federal government encourages the use of cash value life insurance by providing significant tax advantages. Thus, the second advantage of cash value life insurance is tax-advantaged savings.

There are several tax advantages to cash value life insurance. The first and major tax advantage is called "inside buildup." This means that the returns on the investment component of the premium, both income and capital gains, are not subject to taxation (income or capital gains) while held in the insurance contract. Inside buildup is a significant advantage to "saving" via a cash value life insurance policy rather than, for example, saving via a mutual fund.

The second tax advantage of a cash value life insurance policy relates to borrowing against the policy. In general, an amount equal to the cash value of the policy can be borrowed. However, there are some tax implications. The taxation of life insurance is covered in more detail in a following section. In addition to the above, the death benefit, that is the amount paid to the beneficiary of the life insurance contract at the death of the insured, is exempt from income taxes, although it may be subject to estate taxes. This benefit applies both to cash value and pure life insurance.

Term insurance has become much more of a commodity product and, in fact, there are web sites that provide premium quotes for term life insurance for various providers. Cash value life insurance, due to its complexity and multiple features, is not, however, a commodity.

Obviously, the cost of annual term life insurance is much lower than that of whole life insurance, particularly for the young and middle-aged. For example, while there is a wide range of premiums for both term and whole life insurance, for a 35-year-old male, the annual cost of $500,000 of annual term insurance may be $400 and the cost of whole life insurance may be $5,000.

The nature of an insurance company is quite different than that of a traditional manufacturing company. Consider, for a simple comparison, a bread manufacturing company.

The pricing of bread and the calculation of the profits of a bread manufacturing company are quite simple. The bread manufacturer buys flour and other ingredients, produces the bread with its ovens and bakers, and sells the bread soon thereafter. The costs of the inputs are straightforward (the ovens, of course, must be depreciated) and the revenues are received soon after the costs are incurred. Bread prices may be altered as the costs of the inputs vary. Profits can be measured over short periods of time.

The insurance business is much more complex. Premiums—revenues—are determined initially and may be collected once or over a long period of time. The events that trigger an insurance payout are not only deferred but are also contingent on the occurrence of a specified event, for example death or an automobile accident. Since there is a long and uncertain period between the collection of the premium and the payment of the benefit, the receipts may be invested in the interim and the investment returns represent an important but initially uncertain source of revenue. Insurance company investment practices are not considered in this chapter.

Another important distinction between bread manufacturers and insurance companies is the timing of the claim of the customer on the producing company. The purchaser of a loaf of bread is not concerned about the solvency of the bread manufacturer. The purchaser leaves the store with the bread; that is, the business is "cash and carry."

The purchaser of a life insurance contract, however, has a deferred claim on the life insurance company. This claim may arise decades from the purchase of the life insurance contract. For this reason, the customer is concerned about the long-term solvency of the life insurance company. Rating agencies provide credit ratings on life insurance companies to assist customers in this evaluation. The "claims paying ability," as assessed by these rating agencies, may be an important characteristic to customers in their overall choice of a life insurance company.

In addition, to assure that the insurance company will be able to pay the insurance benefit, if necessary, regulators require that the insurance company retain reserves (in an accounting sense) for the security of future payments. Other accounting complexities are also relevant. Thus, overall, the pricing and measurement of the profits of an insurance company are much more complex than that of a bread manufacturer. And to insure that insurance companies are solvent and pay deferred insurance claims, insurance companies are more regulated than bread manufacturers.

Thus, the fundamental difference between bread manufacturers and life insurance companies is that for bread manufacturers the timing of the costs and revenues is approximately synchronous, while for life insurance companies the timing is potentially very different. There are also significant differences in this regard between annual term insurance and whole life insurance. Companies providing annual term life insurance collect the revenue at the beginning of the year and pay the death benefit by the end of the year, if at all. Companies providing whole life insurance, however, may collect premiums for several years and make a large payment after decades.

Stock and Mutual Insurance Companies

There are two major forms of life insurance companies, stock and mutual. A stock insurance company is similar in structure to any corporation (also called a public company). Shares (of ownership) are owned by independent shareholders and may be traded publicly. The shareholders care only about the performance of their shares, that is the stock appreciation and the dividends over time. Their holding period and, thus, their view may be short term or long term. The insurance policies are simply the products or businesses of the company in which they own shares.

In contrast, mutual insurance companies have no stock and no external owners. Their policyholders are their owners. The owners, that is the policyholders, care primarily or even solely about the performance of their insurance policies, notably the company's ability to eventually pay on the policy and to, in the interim, provide investment returns on the cash value of the policy, if any. Since these payments may occur considerably into the future, the policyholders' view will be long term. Thus, while stock insurance companies have two constituencies, their stockholders and their policyholders, mutual insurance companies only have one, since their policyholders and their owners are the same. Traditionally, the largest insurance companies have been mutual, but recently there have been many demutualizations, that is, conversions by mutual companies to stock companies. Currently several of the largest life insurance companies are stock companies.

The debate on which is the better form of insurance company, stock or mutual, is too involved to be considered in any depth here. However, consider selected comments on this issue. First, consider this issue from the perspective of the policyholder. Mutual holding companies have only one constituency, their policyholder or owner. The liabilities of many types of insurance companies are long term, particularly the writers of whole life insurance. Thus, mutual insurance companies can appropriately have a long time horizon for their strategies and policies. They do not have to make short-term decisions to benefit their shareholders, whose interests are usually short term, via an increase in the stock price or dividend, in a way that might reduce their long-term profitability or the financial strength of the insurance company. In addition, if the insurance company earns a profit, it can pass the profit onto its policyholders via reduced premiums. (Policies that benefit from an increased profitability of the insurance company are called participating policies, as discussed later.) These increased profits do not have to accrue to stockholders because there are none.

Finally, mutual insurance companies can adopt a longer time frame in their investments, which will most likely make possible a higher return. Mutual insurance companies, for example, typically hold more common stock in their portfolios than stock companies. However, whereas the long time frame of mutual insurance companies may be construed as an advantage over stock companies, it may also be construed as a disadvantage. Rating agencies and others assert that, due to their longer horizon and their long time frame, mutual insurance companies may be less efficient and have higher expenses than stock companies. Empirically, rating agencies and others assert that mutual insurance companies have typically significantly reduced their expenses shortly before and after converting to stock companies.

Overall, it is argued, mutual insurance companies have such long planning horizons that they may not operate efficiently, particularly with respect to expenses. Stock companies, on the other hand, have very short planning horizons and may operate to the long-term disadvantage of their policyholders to satisfy their stockholders in the short run. Recently, however, mutual insurance companies have become more cost conscientious.

The general account of an insurance company refers to the overall resources of the life insurance company, mainly its investment portfolio. Products "written by the company itself" are said to have a "general account guarantee," that is, they are a liability of the insurance company. When the rating agencies (Moody's, Standard & Poor's, Fitch) provide a credit rating, these ratings are on products written by or guaranteed by the general account, specifically on the "claims-paying ability" of the company. Typical products written by and guaranteed by the general account are whole life, universal life, and fixed annuities (including GICs). Insurance companies must support the guaranteed performance of their general account products to the extent of their solvency. These are called general account products.

Other types of insurance products receive no guarantee from the insurance company's general account, and their performance is based, not on the performance of the insurance company's general account, but solely on the performance of an investment account separate from the general account of the insurance company, often an account selected by the policyholder. These products are called separate account products. Variable life insurance and variable annuities are separate account products. The policyholder selects specific investment portfolios to support these separate account products. The performance of the insurance product depends almost solely on the performance of the portfolio selected, adjusted for the fees or expenses of the insuring company (which do depend on the insurance company). The performance of the separate account products, thus, is not affected by the performance of the overall insurance company's general account portfolio.

Most general account insurance products, including whole life insurance, participate in the performance of the company's general account performance. For example, whereas a life insurance company provides the guarantee of a minimum dividend on its whole life policies, the policies' actual dividend may be greater if the investment portfolio performs well. This is called the "interest component" of the dividend. (The other two components of the dividend are the expense and mortality components.) Thus, the performance of the insurance policy participates in the overall company's performance. Such a policy is called a participating policy, in this case a participating whole life insurance policy.

In addition, the performance of some general account products may not be affected by the performance of the general account portfolio. For example, disability income insurance policies may be written on a general account, and while their payoff depends on the solvency of the general account, the policy performance (e.g., its premium) may not participate in the investment performance of the insurance companies' general account investment portfolio.

Both stock and mutual insurance companies write both general and separate account products. However, most participating general account products tend to be written in mutual companies.

The details of cash value whole life insurance (CVWLI) are very complex. This section provides a simple overview of CVWLI, partially by contrasting it with term life insurance.

As discussed above, in annual term life insurance, the owner of the policy, typically also the insured, pays an annual premium which reflects the actuarial risk of death during the year. The premium, thus, increases each year. If the insured dies during the year, the death benefit is paid to the insurer's beneficiary. If the insured does not die during the year, the term policy has no value at the end of the year.

The construction and performance of CVWLI and term life insurance are quite different. Primarily, the owner of the CVWLI policy pays a constant premium. This premium on the CVWLI policy is initially much higher than the initial premium on a term policy (the pure insurance cost) because the constant premium must cover not only lower insurance risk early in the policy but also higher insurance risk later in the policy when the insured has a higher age and the annual cost of the pure insurance exceeds the level premium. However, assuming the same interest and mortality assumptions on both products, the CVWLI premium should be lower than the average of the term premium over time. This is because in the early years, the excess of the level CVWLI premium over the term premium can earn interest, which lowers the overall premium needed to fund the policy; and some CVWLI policy holders paying the level premium die in the early years, leaving funds (from the excess of the level premium over the early life insurance cost) available to the remaining policy holders, which can be used to decrease the CVWLI premium.

In the early years of the policy, the excess of the premium over the pure insurance cost is invested by the insurance company in its general account portfolio. In the later years, there is a shortfall in the premiums relative to the pure insurance cost and the previous cash value buildup is used to fund this shortfall. This portfolio generates a return which accrues to the policy owner's cash value. Typically, the insurance company guarantees a minimum increase in cash value, called the guaranteed cash value buildup. The insurance company, however, may provide an amount in excess of the guaranteed cash value buildup based on earnings for participating policies. What happens to this excess? Assume that the insurance company has a mutual structure, that is, it is owned by the policyholders. In this case, with no stockholders, the earnings accrue to the policyholders as dividends.

The arithmetic of the development of the cash value in a life insurance contract follows:

+ Premium |

- Cost of Insurance (Mortality) (denoted by M) |

- Expenses (denoted by E) |

+ Guaranteed (Minimum) Cash Value Buildup |

+ (Participating) Dividend |

= Increase (Buildup) in Cash Value |

Note that the overall dividend is calculated from the investment income, the cost of paying the death benefit (the mortality expense denoted by M), and the expense of running the company (denoted by E). The latter two together are called the M&E charges.

If the insurance company is owned by stockholders, some or all of the earnings might go to the stockholders as dividends.

The returns to the insurance company and, therefore, the dividends to the policyholder can increase if: (1) investment returns increase; (2) company expenses decrease; or (3) mortality costs decrease (that is, the life expectancy of the insured increases).

The dividends can be "used" by the policyholder in either of two ways. The first is to decrease the annual premium. In this case, the death benefit remains constant. The second is to increase the death benefit and the cash value of the policy. Such increases are called "paid up additions" (PUAs). In this case, the annual premium remains constant. Most policies are written in the second way.

The intended way for the life insurance policy to terminate is for the insured to die and the life insurance company to pay the death benefit to the beneficiary. There are other ways, however. First, the policy can be lapsed (alternatively called forfeited or surrendered). In this case, the owner of the policy withdraws the cash value of the policy and the policy is terminated.

There are also two nonforfeiture options—that is methods whereby an insurance policy for the insured remains. The owner can use the cash value of the policy to buy extended term insurance (the amount and term of the resulting term insurance policy depends on the cash value). In addition, the cash value of the policy can be used to buy a reduced amount of fully paid (that is, no subsequent premiums are due) whole life insurance—this is called reduced paid up.

In addition to the forfeiture option and the two non-forfeiture options of terminating the CVWLI policy, the policy could be left intact and borrowed against. This is called a policy loan. An amount equal to the cash value of the policy can be borrowed. There are two effects of the loan on the policy. First, the dividend is paid only on the amount equal to the cash value of the policy minus the loan. Second, the death benefit of the policy paid is the policy death benefit minus the loan.

The taxation of the death benefit payout, a policy lapse, and borrowing against the loan are considered next. For taxation of life insurance, it is important to recall that the insurance premium is paid by the policy owner with aftertax dollars (this is often called the cost of the policy). But the cash value is allowed to build up inside the policy with taxes deferred (or usually tax free), often called the return on the policy.

A major attraction of life insurance as an investment product is its taxability. Consider the four major tax advantages of life insurance.

The first tax advantage is that when the death benefit is paid to the beneficiary of the insurance policy, the benefit is free of income tax. If the life insurance policy is properly structured in an estate plan, the benefit is also free of estate taxes.

The second tax advantage is called "inside buildup"— that is, all earnings (interest, dividend, and realized capital gains) are exempt from income and capital gains taxes. Thus, these earnings are tax deferred (and when included in the death benefit become income tax free, and in some cases also estate tax free).

The third relates to the lapse of a policy. When the policy is lapsed, the owner receives the cash value of the policy. The amount taxed is the cash value minus the cost of the policy (the total premiums paid plus the dividends, if paid in cash). That is, the tax basis of the policy is the cost (accumulated premiums) of the policy. The cost, thus, increases the basis and is recovered tax free. (Remember, however, that these costs were paid with after-tax dollars.) And, the remainder was allowed to accumulate without taxation but is taxed at the time of the lapse.

The fourth tax issue relates to borrowing against the policy—that is, a policy loan. The primary tax issue is the distinction between the cost (accumulated premium) and the excess of the policy cash value over the cost (call it the excess). When a policy loan is made, the cost is deemed to be borrowed first (that is, FIFO [first in-first out] accounting is employed). The amount up to the cash value of the policy can be borrowed and not be subject to the ordinary income tax. (An exception to this practice is for a modified endowment contract (MEC). If the loan is outstanding at the time of the policy lapse, the loan is treated on a FIFO basis whereby the cost basis is assumed to be borrowed first and is not taxable, and when the cost basis is exhausted by the loan, the remainder of the loan [up to the cash value of the policy] is taxable.)

Although CVWLI has both insurance and investment characteristics, Congress provided insurance policies tax advantages because of their insurance, not their investment, characteristics. And Congress does not wish to apply these insurance-directed tax benefits to primarily investment products. In this regard, in the past some activities related to borrowing against insurance policies were considered abuses by Congress and tax law changes were made to moderate these activities. These abuses originated with a product called single-premium life insurance. This policy is one in which only a single premium is paid for a whole life insurance policy. The premium creates an immediate cash value. This cash value and the resulting investment income earned are sufficient to pay the policy's benefits. The excess investment income accumulates tax free.

After the elimination of many tax shelters by the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the sale of single-premium life insurance accelerated significantly because investors found this product to be an attractive tax shelter. Large amounts could be paid as a premium, the earnings grew tax free, and the owner could borrow up to the cash value without a tax liability. Single-premium life insurance thus generated significant tax-sheltered investment income.

In 1988 (via the Technical and Miscellaneous Revenue Act of 1988, TAMRA), Congress developed a new policy to discourage the use of life insurance contracts with large premiums as an investment tax shelter. The test embodied in this policy was called the seven-pay test. Consider first the effect of not meeting the seven-pay test, and then the test itself.

If an insurance policy did not meet the seven-pay test at time of issue, it was deemed to be a modified endowment contract and the tax advantages were reduced as follows. MECs have two important tax disadvantages relative to standard life insurance policies (non-MECs). First, policy loans on a MEC are made on a LIFO (last in-first out) basis—that is, the investment earnings, not the cost basis, is borrowed first and is taxable. The remainder of the loan up to the cash value of the policy is the cost basis and not subject to tax. Second, MECs are subject to a 10% penalty on any taxable gains borrowed before age 59.5 (similar provisions exist on annuities, as discussed in a later section).

Next consider the seven-pay test for determining whether the policy is an MEC. The seven-pay test is an artificial standard developed by the IRS based on the level premium concept. First, the premium for a level premium seven-year paid policy is calculated. The test or standard for determining whether an insurance policy is an MEC is that the premium actually paid on the policy during the first seven years cannot be greater than the seven-year pay level on a year-by-year basis. For example, if the seven-year pay amount calculated is $1,000 per year for seven years, the premium paid can be no more than $1,000 during the first year; similarly no more than $2,000 during the first two years; and up to $7,000 during the first seven years. If the actual premiums paid are greater than any of these amounts, the policy is an MEC. Whether or not a policy is an MEC should be determined and be divulged to the policy owner before the policy is written.

If a policy is deemed a MEC when it is written, it remains a MEC throughout its life. However, a policy that is initially a non-MEC can be subsequently deemed to be an MEC if premium payments accelerate.

The following illustrates the difference in the taxation of an MEC and a non-MEC.

Cash Value: | 100 |

Premium Paid: | 20 |

Earnings: | 80 |

Non-MEC

Loan up to 100 is nontaxable (that is, neither premium paid nor earnings is taxable)

Rationale: withdrawal is a loan, not a distribution (that is, not included in income)

MEC

Borrow earnings (80) first—is taxable

Then borrow premium paid (20)—is not taxable

The characteristics of MECs and non-MECs are summarized in Table 62.4. It is important to note that MECs have no disadvantage if the policy owner does not borrow against the policy. The MEC condition serves only to disadvantage policy loans in an insurance contract.

The major investment-oriented insurance products can be divided into two categories—cash value life insurance and annuities. Each has several types, which are listed in Table 62.2. These products are described in the following sections.

Cash value life insurance was introduced above. There are two dimensions of cash value life insurance policies. The first is whether the cash value is guaranteed (called whole life) or variable (called variable life). The second is whether the required premium payment is fixed or flexible, that is, whether it has a universal (flexible) feature or not. They can be combined in all ways. Thus, there are four combinations, which we discuss next. The broad classification of cash value life insurance, called whole life insurance, in addition to providing pure life insurance (as does term insurance), builds up a cash value or investment value inside the policy.

Table 62.4. Characteristics of Non-MECs and MECs

Non-MEC | MEC |

|---|---|

Meets seven-pay test. | Does not meet seven-pay test. |

Inside buildup is tax deferred. | Inside buildup is tax deferred. |

Can borrow up to cash value of the policy. | Can borrow up to cash value of the the policy. |

Loans are tax free. | Loans are treated on LIFO basis (investment income i s borrowed first). |

Pay income tax on investment income borrowed first (with 10% penalty on earning if before age 59.5); no tax on remainder of loan up to cash value. | |

No disadvantage if do not borrow against or surrender the policy). |

Traditional cash value life insurance, usually called whole life insurance, has a guaranteed buildup of cash value based on the investment returns on the general account portfolio of the insurance company. That is, the cash value in the policy is guaranteed to increase by a specified minimum amount each year. This is called the cash value buildup. (The guaranteed cash value buildup of many U.S. CVWLI policies tend to be in the range of 3%-4%.) The cash value may grow by more than this minimum amount if a dividend is paid on the policy. Dividends, however, are not guaranteed. There are two types of dividends, participating and nonparticipating. Participating dividends depend on (that is, participate in) the investment returns of the general account of the insurance company portfolio (the insurance company M&E charges also affect the dividend).

The participating dividend may be used to increase the cash value of the policy by more than its guaranteed amount. Actually, there are two potential uses of the dividend. The first is to reduce the annual premium paid on the policy. In this case, while the premium decreases, the cash value of the policy increases by only its guaranteed amount (and the face value the death benefit remains constant).

The second use is to buy more life insurance with the premium (called "paid-up additions," PUA). In this case, the cash value of the entire policy increases by more than the guaranteed amount on the original policy (and the face value of the current policy is greater than the face value of the original policy).

In either case, the performance of the policy over time may be substantially affected by the participating dividends.

Contrary to the guaranteed or fixed cash value policies based on the general account portfolio of the insurance company, variable life insurance polices allow the policyowners to allocate their premium payments to and among several separate investment accounts maintained by the insurance company, and also to be able to shift the policy cash value among these separate accounts. As a result, the amount of the policy cash value depends on the investment results of the separate accounts the policyowners have selected. Thus, there is no guaranteed cash value or death benefit. Both depend on the performance of the selected investment portfolio.

The types of separate account investment options offered in their variable life insurance policies vary by insurance companies. Typically, the insurance company offers a selection of common stock and bond fund investment opportunities, often managed by the company itself and also by other investment managers. If the investment options perform well, the cash value buildup in the policy will be significant. However, if the policyholder selects investment options that perform poorly, the variable life insurance policy will perform poorly. There could be little or no cash value buildup, or, in the worst case, the policy could be terminated because there is not enough value in the contract to pay the mortality charge. This type of cash value life insurance is called variable life insurance.

Table 62.5. Types of Cash Value Life Insurance

Premium | Guaranteed | Variable |

|---|---|---|

Fixed | Whole life | Variable |

Flexible | Universal life | Variable universal life |

The key element of universal life is the flexibility of the premium for the policyowner. The flexible premium concept separates the pure insurance protection (term insurance) from the investment (cash value) element of the policy. The policy cash value is set up as a cash value fund (or accumulation fund) to which the investment income is credited and from which the cost of term insurance for the insured (the mortality charge) is debited. The policy expenses are also debited.

This separation of the cash value from the pure insurance is called the "unbundling" of the traditional life insurance policy. Premium payments for universal life are at the discretion of the policyholder, that is, are flexible with the exceptions that there must be a minimum initial premium to begin the coverage, and there must also be at least enough cash value in the policy each month to cover the mortality charge and other expenses. If not, the policy will lapse. Both guaranteed cash value and variable life can be written on a flexible premium or fixed premium basis.

The universal feature—flexible premiums—can be applied to either guaranteed value whole life (called simply universal life) or to variable life (called variable universal life). These types are summarized in Table 62.5. Variable universal life insurance combines the features of variable life and universal life policies—that is, the choice of separate account investment products and flexible premiums.

Over the last decade, term and variable life insurance have been growing at the expense of whole life insurance. The most common form of variable life is variable universal.

Most whole life insurance policies are designed to pay death benefits when one specified insured dies. An added dimension of whole life policies is that two people (usually a married couple) are jointly insured, and the policy pays the death benefit not when the first person dies, but when the second person (the "surviving spouse") dies. This is called survivorship insurance or second-to-die insurance. This survivorship feature can be added to standard cash value whole life, universal life, variable life, and variable universal life policies. Thus, each of the four policies discussed could also be written on a survivorship basis.

In general, the annual premium for a survivorship insurance policy is lower than for a policy on a single person because, by construction, the second of two people to die has a longer life span than the first. Survivorship insurance is typically sold for estate planning purposes.

Table 62.6 provides a summary of the various types of cash value life insurance, with (annual renewable) term insurance included for contrast.

Table 62.6. Life Insurance Comparison (By Type and Element)

Type | Description | Death Benefit | Premium | Cash Value (CV) | Advantages to Owner | Disadvantages to Owner |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Annual renewable term | "Pure" life insurance with no cash value; initially, the highest death benefit for the lowest premium; premium increases exponentially | Fixed, constant | Increases exponentially | None | Low premium for coverage | Increasing premium; most term insurance is lapsed |

Whole life | Known maximum cost and minimum death benefit; dividends may: reduce premiums; pay-up policy; buy paid-up additions; accumulate at interest; or be paid in cash | Fixed, constant | Fixed, constant | Fixed | Predictable; forced savings and conservative investment | High premiums given death benefit |

Variable life | Whole life contract; choice of investment assets; death benefits depend on investment results | Guaranteed minimum; can increase based on investment performance | Fixed, constant | Based on investment performance; not guaranteed. | Combines life insurance and investments on excess premiums | All investment risk is to the owner |

Universal life | Flexible premium, current assumption adjustable death benefit policy; policy elements unbundled | Adjustable; Two options: 1. like ordinary life; 2. like ordinary life plus term rider equal to cash value. | Flexible at option of policy owner | Varies depending on face amount and premium; minimum guaranteed interest; excess increases cash value. | Flexibility | Some investment risk to owner |

Variable universal life | Features of universal and variable life | Adjustable | Flexible at option of policy owner | Varies depending on face amount, premium, and investment performance; not guaranteed. | Flexibility and choice of investments | All investment risk is to owner |

The standard use of life insurance is to protect the survivors of an income earner. In this case, the insured is the income earner and the survivors are the beneficiaries. This is still a major use of life insurance. For this use, life insurance protects against premature death.

There are, however, many other uses. The life insurance death benefits are used to pay the estate taxes on the deceased's assets in their estate. There are also many business uses of life insurance. Split dollar life insurance, whereby the business pays for a portion or all of the premium on a life insurance policy on the executive, is used as a fringe benefit for its executives. Life insurance policies may also be written on both participants in a partnership to fund the purchase by the surviving partner of the ownership of the deceased partner according to a buy-sell agreement. There are also other business uses of life insurance.

By definition, an annuity is simply a series of periodic payments. Annuity contracts have been offered by insurance companies and, more recently, by other types of financial institutions such as mutual fund companies.

There are two phases to annuities according to cash flows, the accumulation period and the liquidation period. During the accumulation period, the investor is providing funds, or investing. Annuities are considered primarily accumulation products rather than insurance products. During the liquidation period, the investor is withdrawing funds, or liquidating the annuity. One type of liquidation is annuitization, or withdrawal via a series of fixed payments, as discussed below. This method of liquidation is the basis for the name of annuities.

There are several ways to classify annuities. One is the method of paying premiums. Annuities are purchased with single premiums, fixed periodic premiums, or flexible periodic premiums during the accumulation phase. All three are used in current practice.

A second classification is the time the income payments commence during the liquidation phase. An immediate annuity is one in which the first benefit payment is due one payment interval (month, year or other) from the purchasing date. Under a deferred annuity, there is a longer period before the benefit period begins. While an immediate annuity is purchased with a single premium, a deferred annuity may be purchased with a single, fixed periodic, or flexible periodic payments, although the flexible periodic payment is most common.

An important basis for annuities is whether they are fixed or variable annuities. Fixed annuities, as discussed in more detail below, are expressed in a fixed number of dollars, while variable annuities are expressed in a fixed number of annuity units, each unit of which may have a different and changing market value. Fixed versus variable annuities is the key distinction between annuities currently provided.

Now we will look at the various types of annuities. The most common categories are variable annuities and fixed annuities.

While cash value life insurance has the appearance of life insurance with an investment feature, annuities, in contrast, have the appearance of an investment product with an insurance feature. The major advantage of an annuity is its inside buildup, that is, its investment earnings are tax deferred. However, unlike life insurance where the death benefit is not subject to income taxes, withdrawals from annuities are taxable. There are also restrictions on withdrawals. Specifically, there are IRS requirements for the taxability of early withdrawals (before age 59.5) and required minimum withdrawals (after age 70.5). These requirements and the other tax issues of annuities are very complex and considered only briefly here.

The most common types of annuities, variable and fixed annuities, are discussed below.

Variable Annuities

Variable annuities are, in many ways, similar to mutual funds. Given the above discussion, variable annuities are often considered to be "mutual funds in an insurance wrapper." The return on a variable annuity depends on the return of the underlying portfolio. The returns on annuities are, thus, in a word, "variable." In fact, many investment managers offer similar or identical funds separately in both a mutual fund and an annuity format. Thus, variable annuity offerings are approximately as broad as mutual fund offerings. For example, consider a large capitalization, blended stock fund. The investment manager may offer this fund in both a mutual fund and annuity format. But, of course, the two portfolios are segregated. The portfolios of these two products maybe identical and, thus, the portfolio returns will be identical.

Before considering the differences, however, there is one similarity. Investments in both mutual funds and annuities are made with after-tax dollars; that is, taxes are paid on the income before it is invested in either a mutual fund or an annuity.

But there are important differences to investors in these two products. First, all income (dividend and interest) and realized capital gains generated in the mutual fund are taxable, even if they are not withdrawn. However, income and realized capital gains generated in the annuity are not taxable until withdrawn. Thus, annuities benefit from the same inside buildup as cash value life insurance.

There is another tax advantage to annuities. If a variable annuity company has a group of annuities in its family (called a "contract"), an investor can switch from one annuity fund to another in the contract (for example from a stock fund to a bond fund) and the switch is not a taxable event. However, if the investor shifts from a stock fund in one annuity company to a bond fund in another annuity company, it is considered a withdrawal and a reinvestment, and the withdrawal is a taxable event (there are exceptions to this, however, as will be discussed). The taxation of annuity withdrawals will also be considered.

While the inside buildup is an advantage of annuities, there are offsetting disadvantages. For comparison, there are no restrictions on withdrawals from (selling shares of) a mutual fund. Of course, withdrawals from a mutual fund are a taxable event and will generate realized capital gains or losses, which will generate long-term or short-term gains or losses and, thus, tax consequences. There are, however, significant restrictions on withdrawals from annuities. First, withdrawals before age 59.5 are assessed a 10% penalty (there are, however, some "hardship" exceptions to this). Second, withdrawals must begin by age 70.5 according to the IRS required minimum distribution rules (RMD). These mandatory withdrawals are designed to eventually produce tax revenues on annuities to the IRS. Mutual funds have no disadvantages to withdrawing before 59.5 nor requirements to withdraw after 70.5.

There is an exception to the taxation resulting from a shift of funds from one variable annuity company to another. Under specific circumstances, funds can be so moved without causing a taxable event. Such a shift is called a 1035 exchange after the IRS rule that permits this transfer.

Another disadvantage of annuities is that all gains on withdrawals, when they occur, are taxed as ordinary income, not capital gains, whether their source was income or capital gains. For many investors, their income tax rate is significantly higher than the long-term capital gains tax rate and this form of taxation is therefore a disadvantage.

The final disadvantage of annuities is that the heirs of a deceased owner receive them with a cost basis equal to the purchase price (which means that the gains are taxed at the heir's ordinary income tax rate) rather than being stepped up to a current market value as with most investments.

Why has the IRS given annuities the same tax advantage of inside buildup that insurance policies have? The answer to this question is that annuities are structured to have some of the characteristics of life insurance, commonly called "features." There are many such features. The most common feature is that the minimum value of an annuity fund that will be paid at the investor's death is the initial amount invested. Thus, if an investor invests $100 in a stock annuity, the stock market declines such that the value of the fund is $90, and the investor dies, the investor's beneficiary will receive $100, not $90. This is a life insurance characteristic of an annuity.

The above feature represents a death benefit (DB), commonly called a return of premium. However, new, and often more complicated, death benefits have been introduced, including a periodic lock-in of gains (called a "stepped up" DB); a predetermined annual percentage increase (called a "rising floor" DB); or a percentage of earnings to offset estate taxes and other death expenses (called an "earnings enhancement" DB). In addition to these death benefit features, some living benefit features have also been developed, including premium enhancements and minimum accumulation guarantees.

Obviously, these features have value to the investor and, as a result, a cost to the provider. The value of a feature depends on its design and can be high or approximately worthless. And the annuity company will charge the investor for the value of these features.

The cost of the features relates to another disadvantage of annuities, specifically their expenses. The insurance company will impose a charge for the potential death benefit payment (called mortality) and other expenses, overall called M&E charges, as discussed previously for insurance policies. These M&E charges will be in addition to the normal investment management, custody, and other expenses experienced by mutual funds. Thus, annuity expenses will exceed mutual fund expenses by the annuity's M&E charges. The annuity investor does, however, receive the value of the insurance feature for the M&E charge.

Thus, the overall trade-offs between mutual funds and annuities can be summarized as follows. Annuities have the advantages of inside buildup and the particular life insurance features of the specific annuity. But annuities also have the disadvantages of higher taxes on withdrawal (ordinary income versus capital gains), restrictions on withdrawals, and higher expenses. For short holding periods, mutual funds will have a higher after-tax return. For very long holding periods, the value of the inside buildup will dominate and the annuity will have a higher after-tax return.

What is the breakeven holding period, that is, the holding period beyond which annuities have higher after-tax returns? The answer to this question depends on several factors, such as the tax rates (income and capital gains), the excess of the expenses on the annuity, and others.

Fixed Annuities

There are several types of fixed annuities but, in general, the invested premiums grow at a rate—the credited rate—specified by the insurance company in each. This growth is accrued and added to the cash value of the annuity each year (or more frequently, such as monthly) and is not taxable as long as it remains in the annuity. Upon liquidation, it is taxed as ordinary income (to the extent that is represents previously untaxed income).

The two most common types of fixed annuities are the flexible-premium deferred annuity (FPDA) and the single-premium-deferred annuity (SPDA). The FPDA permits contributions which are flexible in amount and timing. The interest rate paid on these contracts—the credited rate—varies and depends on the insurance company's current interest earnings and its desired competitive position in the market. There are, however, two types of limits on the rate. First, the rate is guaranteed to be no lower than a specified contract guaranteed rate, often in the range 3% to 4%. Second, these contracts often have bailout provisions, which stipulate that if the credited rate decreases below a specified rate, the owner may withdraw all the funds (lapse the contract) without a surrender charge. Bailout credited rates are often set at 1% to 3% below the current credited rate and are designed to limit the use of a "teaser rate" (or "bait and switch" practices), whereby an insurance company offers a high credited rate to attract new investors and then reduces the credited rate significantly, with the investor limited from withdrawing the funds by the surrender charges.

An initial credited rate, a minimum guaranteed rate, and a bailout rate are set initially on the contract. The initial credited rate, thus, may be changed by the insurance company over time. The reset (or renewal) period must also be specified—this is, the frequency with which the credited rate can be changed.

Another important characteristic of annuities is the basis for the valuation of withdrawals prior to maturity. The traditional method has been book value, that is, withdrawals are paid based on the purchase price of the bonds (bonds rather than stocks are used to fund annuities). Thus, if yields have increased, the insurance company will be paying the withdrawing investor more than the bonds are currently worth. And at this time, there is an incentive for the investor to withdraw and invest in a new higher yielding fixed annuity. Thus, book value fixed annuities provide risk to the insurance company. Surrender charges, discussed next, mitigate this risk. Another way to mitigate this risk is via market value adjusted (MVA) annuities, whereby early withdrawals are paid on the basis of the current market value of the bond portfolio rather than the book value. This practice eliminates the early withdrawal risk to the insurance company. (Obviously, all variable annuities are paid on the basis of market value rather than bonds value.)

Another characteristic of both variable and fixed annuities relates to one aspect of their sales charges. These charges are very similar for annuities and mutual funds. Mutual funds and annuities were originally provided with front-end loans, that is, sales charges imposed on the initial investment. For example, with a 5% front-end load of a $100 initial investment, $5 would be retained by the firm for itself and the agent, and $95 invested in the fund for the investor.

More recently, back-end loads have been used as an alternative to front-end loads. With a back-end load, the fixed percentage charge is imposed at the time of withdrawal. Currently, the most common form of back-end load is the contingent deferred sales charge (CDSC), also called simply a surrender charge. This approach imposes a load which is gradually declining over time. For example, a common CDSC is a "7%/6%/5%/4%/3%/2%/l%/0%" charge according to which a 7% load is imposed on withdrawals during the first year, 6% during the second year, 5% during the third year, and so forth. There is no charge for withdrawals after the seventh year.

Finally, there are level loads, which impose a constant load (1% for example) every year. Currently on annuities, a front-end load is often used along with a CDSC surrender charge.

Annuities have become very complex instruments. This section provides only an overview.

Guaranteed Investment Contracts

The first major investment-oriented product developed by life insurance companies, and a form of fixed annuity, was the guaranteed investment contract (GIC). GICs were used extensively for retirement plans. With a GIC, a life insurance company agrees, in return for a single premium, to pay the principal amount and a predetermined annual crediting rate over the life of the investment, all of which are paid at the maturity date of the GIC. For example, a $10 million five-year GIC with a predetermined crediting rate of 10% means that at the end of five years, the insurance company pays the guaranteed crediting rate and the principal. The return of the principal depends on the ability of the life insurance company to satisfy the obligation, just as in any corporate debt obligation. The risk that the insurer faces is that the rate earned on the portfolio of supporting assets is less than the guaranteed rate.

The maturity of a GIC can vary from 1 year to 20 years. The interest rate guaranteed depends on market conditions and the rating of the life insurance company. The interest rate will be higher than the yield on U.S. Treasury securities of the same maturity. These policies are typically purchased by pension plan sponsors as a pension investment.

A GIC is a liability of the life insurance company issuing the contract. The word guarantee does not mean that there is a guarantor other than the life insurance company. Effectively, a GIC is a zero-coupon bond issued by a life insurance company and, as such, exposes the investor to the same credit risk. This credit risk has been highlighted by the default of several major issuers of GICs. The two most publicized defaults were Mutual Benefit, a New Jersey-based insurer, and Executive Life, a California-based insurer, which were both seized by regulators in 1991.

The basis for these defaults is that fixed annuities are insurance company general account products and variable annuities are separate account products. For fixed annuities, the premiums become part of the insurance company, are invested in the insurance company's general account (which are regulated by state laws), and the payments are the obligations of the insurance company. Variable annuities are separate account products, that is, the premiums are deposited in investment vehicles separate from the insurance company, and are usually selected by the investor. Thus, fixed annuities are general account products and the insurance company bears the investment risk, while variable annuities are separate account products and the investor bears the investment risk.

SPDAs and GICs

SPDAs and GICs with the same maturity and crediting rate have much in common. For example, for each the value of a $1 initial investment with a 5-year maturity and a fixed crediting rate for the 5 years at r% would have a value at maturity of (1 + r)5.

However, there are also significant differences. SPDAs have elements of an insurance product and so its inside buildup is not taxed as earned (it is taxed as income at maturity). SPDAs are not qualified products, that is, they must be paid for in after tax-dollars. GICs are not insurance products. GICs, however, are typically put into pension plans (defined benefit or defined contribution), which are qualified. In this case, thus, the GIC investments are paid for in after-tax dollars and receive the tax deferral of inside buildup. SPDAs are also put into qualified plans. Specifically, banks often sell IRAs funded with SPDAs.

Another difference between SPDAs and GICs is that since SPDAs are annuities, they usually have surrender charges, typically the 7%/6%/5%/4%/3%/2%/l%/0%, mentioned previously. Thus, if a 5-year SPDA is withdrawn after three years, there is a 4% surrender charge. GICs do not have surrender charges and can be withdrawn with no penalty (under benefit responsive provisions).

Another feature of SPDAs is the reset period, the period after which the credited rate can be changed by the writer of the product. For example, a 5-year SPDA may have a reset period after three years, at which time the credited rate can also be increased or decreased. For SPDAs, there can also be an interaction between the reset period and the surrender charge. For example, a 5-year SPDA with a 3-year reset period could be liquidated after 3 years due to a lowered crediting rate, but only with a 4% surrender charge. GICs have no reset period, that is, the credited rate is constant throughout the contract's life. Early withdrawals of GICs are at book value; they are interest rate insensitive.

SPDAs typically have a reset period of 1 year but with an initial M-year minimum guarantee (M = 1,2,3,5,7,9). SPDAs typically have a maturity based on the age of the annuitant (such as age 90 or 95), not a fixed number of years. Thus, while SPDAs typically have a maturity greater than the guarantee period, for GICs the maturity period equals the guarantee period. Common maturities for GICs and SPDAs are 1, 3, 5, and 7 years.

Annuitization

Strictly speaking, an annuity is a guaranteed (or fixed) amount of periodic income for life. Both variable and fixed annuities are accumulation products rather than income products. Either product can, however, be annuitized—that is, converted into a guaranteed lifetime income. Annuitization refers to the liquidation rather than the accumulation period. As a matter of fact, very few of variable annuities are annuitized. One reason that few investors annuitize is that they fear they will die early and receive very little for the initial investment. On the other hand, the risk to individuals is that they will outlive their savings. Annuitization eliminates this risk. Traditionally, defined benefit retirement plans have provided a lifetime flow of income. But with the decline in defined benefit retirement plans, annuities can fill this vacuum.

Since the fixed payments of an annuity are for life, there is mortality risk for the annuity writer. If the annuitant dies soon, the payout by the annuity writer will be small. However, if the annuitant lives a long life, the payments by the annuity writer will be large. This characteristic introduces an underwriting element to annuities by the annuity writer. Some fixed annuities also have a survivorship feature. That is, when the annuitant dies, the payments will continue and be paid to a named survivor, usually a spouse.

Many variable annuity owners who wish to annuitize elect for a variation on a strict annuity called a systematic withdrawal plan (SWP) instead. While there are many types of SWPs, the most common type is based on a specified term rather than lifetime payments in order to assure that the payments last at least a certain amount of time (called a period-certain payout option). These plans, thus, do not eliminate the risk of outliving one's savings. Under a SWP, annuity shares are liquidated to pay regular payments that are either a fixed dollar amount or a percentage of the investor's account balance. Thus, unlike annuitization, SWPs cause a continual decline in the investor's account balance. There are also variations of the standard lifetime payout option which include life with a guaranteed period, joint and survivor life, and joint and survivor life with a guaranteed period.

Fundamentally, insurance and investment products are distinct. Insurance products provide risk protection against a wide variety of risks and have no cash value. Investment products, often called accumulation products, provide returns on an initial investment.

However, two types of products provide elements of both insurance and investments. These two are cash value life insurance and annuities. Cash value life insurance is a combination of pure life insurance with a buildup of cash value as a result of the higher premium paid relative to a pure life insurance policy. The types of cash value life insurance include whole life and variable life, and universal versions of both of these.

The second type is annuities. There are two types of annuities, variable and fixed. Variable annuities are essentially mutual funds in an insurance wrapper. The insurance elements may include both death benefits and living benefits. The returns on variable annuities depend on the particular type of investment portfolio selected by the investor.

Fixed annuities are a guaranteed yield over an investment term. The return over the term is specified at the time of the investment and is certain. Very few annuities, variable or fixed, are annuitized, that is, converted into a lifetime stream of fixed payments, despite the attractive characteristics of annuitization.

The investment element of these hybrid insurance/investment products benefits from their tax advantages. The major tax advantage of both of these types of investment-oriented insurance products is inside buildup, although the cash value life insurance products also have other significant tax benefits. Congress provided the tax advantages to these products due to their insurance characteristics, not their investment characteristics. There are, as a result, limits on the investment characteristics of these hybrid products to qualify them for the tax advantages.

Baldwin, B. (2002). New Life Insurance Investment Advisor: Achieving Financial Security for You and Your Family Through Today's Insurance Products, 2nd ed., New York: McGraw-Hill.

Dellinger, J. K. (2006). The Handbook of Variable Income Annuities. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Graves, E. E., and Hayes, L. (eds.) (1994). McGill's Life Insurance. Bryn Mawr, PA: Hueber School Series, The American College.

Milevsky, M. A. (2006). The Calculus of Retirement Income: Financial Models for Pension Annuities and Life Insurance. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shunt, L. S. (2003). The Life Insurance Handbook. New York: Marketplace Books.

Weber, R. M. (2005). Revealing Life Insurance Secrets: How the Pros Pick, Design, and Evaluate Their Own Policies. New York: Marketplace Books.