MOORAD CHOUDHRY, PhD

Head of Treasury, KBC Financial Products, London

Abstract: Bond spreads are used to determine relative value in bonds that are not credit risk free. This relative value is a measure of the risk premium return implied in the bond yield. To calculate bond spread, we may use one of four different measures, which are described and illustrated in this chapter. Investors can also determine relative value in the cash market by comparing its yield spread with that observed in the synthetic market, which is represented by the credit default swap premium payable for the same reference name. The spread difference between the two markets is known as the credit default swap basis and the existence of the basis implies arbitrage opportunities between the two markets.

Keywords: asset swap, credit default swaps (CDSs), basis, bond spread, interpolated spread, relative value, swap spread, zero-volatility spread (Z-spread)

In this chapter we consider the methods by which the value of a bond can be ascertained by comparing its yield to that of another bond or benchmark interest rate. Whichever method is used to calculate it, this measure is important for investors, as it is an indication of relative value and, as such, the main method by which they gauge whether it is worthwhile to hold the bond and if its risk-reward profile is acceptable. The methods that can be used reflect the differences in measuring yield in cash and derivative markets, and include the interpolated spread, Treasury spread, and asset-swap spread. We also discuss the difference in yield between cash and synthetic credit markets, known as the credit derivative basis, and how this influences the measurement of bond relative value.

Investors measure the perceived market value, or relative value, of a corporate bond by measuring its yield spread relative to a designated benchmark. This is the spread over the benchmark that gives the yield of the corporate bond. A key measure of relative value of a corporate bond is its swap spread. This is the basis-point spread over the interest rate swap curve, and is a measure of the credit risk of the bond. In its simplest form, the swap spread can be measured as the difference between the yield to maturity of the bond and the interest rate given by a straight-line interpolation of the swap curve. In practice, traders use the asset swap spread and the zero-volatility spread (Z-spread) as the main measures of relative value. The government bond spread is also used. In addition, now that the market in synthetic corporate credit is well established, using credit derivatives and credit default swaps (CDSs), investors may consider the cash-CDS spread as well, which is the basis and which we consider in greater detail later.

The spread that is selected is an indication of the relative value of the bond, and a measure of its credit risk. The greater the perceived risk, the greater the spread should be. This is best illustrated by the credit structure of interest rates, which will (generally) show AAA- and AA-rated bonds trading at the lowest spreads and BBB, BB, and lower-related bonds trading at the highest spreads. Bond spreads are the most commonly used indication of the risk-return profile of a bond.

In this section we consider the Treasury spread, asset swap spread, Z-spread, and basis. A bond's swap spread is a measure of the credit risk of that bond, relative to the interest rate swaps market. Because the swaps market is traded by banks, this risk is effectively the interbank market, so the credit risk of the bond over and above bank risk is given by its spread over swap rates. This is a simple calculation to make, and is simply the yield of the bond minus the swap rate for the appropriate maturity swap.

The spread over swaps is sometimes called the I-spread. It has a simple relationship to swaps and Treasury yields, shown here in the equation for corporate bond yield:

where

| Y = yield on the corporate bond |

| I = I-spread or spread over swap |

| S = swap spread |

| T = yield on the Treasury security (or an interpolated yield |

In other words, the swap rate itself is given by T + S.

The I-spread is sometimes used to compare a cash bond with its equivalent CDS price, but for straightforward relative value analysis it is usually dropped in favor of the asset swap spread, which we look at later in this section.

Of course, the basic relative value measure is the Treasury spread or government bond spread. This is simply the spread of the bond yield over the yield of the appropriate government bond. Again, an interpolated yield may need to be used to obtain the right Treasury rate to use. The bond spread is given by:

Using an interpolated yield is not strictly accurate because yield curves are smooth in shape, and so straight-line interpolation will produce slight errors. Despite this, the method is still commonly used by market practitioners.

An asset swap is a package that combines an interest rate swap with a cash bond, the effect of the combined package being to transform the interest rate basis of the bond. Typically, a fixed-rate bond will be combined with an interest rate swap in which the bondholder pays fixed coupon and receives floating coupon. The floating coupon will be a spread over the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) (see Choudhry et al., 2001). This spread is the asset swap spread and is a function of the credit risk of the bond over and above interbank credit risk. (This is because in the interbank market, two banks transacting an interest rate swap will be paying/receiving the fixed rate and receiving/paying LIBOR flat.) Asset swaps may be transacted at par or at the bond's market price, usually par. This means that the asset swap value is made up of the difference between the bond's market price and par, as well as the difference between the bond coupon and the swap fixed rate.

The zero-coupon curve is used in the asset swap valuation. This curve is derived from the swap curve, so it is the implied zero-coupon curve. The asset swap spread is the spread that equates the difference between the present value of the bond's cash flows, calculated using the swap zero rates, and the market price of the bond. This spread is a function of the bond's market price and yield, its cash flows, and the implied zero-coupon interest rates. (Bloomberg refers to this spread as the "gross spread.")

For example, on August 10, 2005, a U.K. pound sterling (GBP)-denominated corporate bond, GKN Holdings 7% 2012, was observed to have a an asset swap spread of 121.5 basis points. This is the spread over LIBOR that will be received if the bond is purchased in an asset swap package. In essence, the asset swap spread measures a difference between the market price of the bond and the value of the bond when cash flows have been valued using zero-coupon rates. The asset swap spread can therefore be regarded as the coupon of an annuity in the swap market that equals this difference.

The conventional approach for analyzing an asset swap uses the bond's yield-to-maturity (YTM) in calculating the spread. The assumptions implicit in the YTM calculation (see Chapter 17 in Volume I) make this spread problematic for relative analysis, so market practitioners use what is termed the "zero-volatility" or "Z-spread" instead. The Z-spread uses the zero-coupon yield curve to calculate spread, so is a more realistic and effective spread to use. The zero-coupon curve used in the calculation is derived from the interest rate swap curve.

Put simply, the Z-spread is the basis-point spread that would need to be added to the implied spot yield curve such that the discounted cash flows of a bond are equal to its present value (its current market price). Each bond cash flow is discounted by the relevant spot rate for its maturity term. How does this differ from the conventional asset swap spread? It differs essentially in its use of zero-coupon rates when assigning a value to a bond. Each cash flow is discounted using its own particular zero-coupon rate. A bond's price at any time can be taken to be the market's value of the bond's cash flows. Using the Z-spread, we can quantify what the swap market thinks of this value, that is, by how much the conventional spread differs from the Z-spread. Both spreads can be viewed as the coupon of a swap market annuity of equivalent credit risk of the bond being valued.

In practice, the Z-spread, especially for shorter-dated bonds and for better credit-quality bonds, does not differ greatly from the conventional asset-swap spread. The Z-spread is usually the higher spread of the two, following the logic of spot rates, but not always. If it differs greatly, then the bond can be considered to be mispriced.

Taking the same bond mentioned earlier and as at the same date, we observed a number of different spreads for the bond. The main spread of 151.00 bps was the spread over the government yield curve. This is an interpolated spread over the appropriate benchmark sovereign bond. The asset swap spread was 121.5 bps as stated earlier, while the Z-spread was 118.8 bps. When undertaking relative value analysis, for instance if making comparisons against cash funding rates or the same company name CDS, it is this lower spread that should be used.

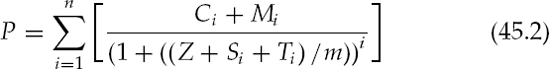

The Z-spread is closely related to the bond price, as shown by

where

| n = number of interest periods until maturity |

| P = bond price |

| C = coupon |

| M = redemption payment (so bond cash flow is all C plus M) |

| Z = Z-spread |

| m = frequency of coupon payments |

In effect, this is the standard bond price equation, with the discount rate adjusted by whatever the Z-spread is; it is an iterative calculation. The appropriate maturity swap rate is used, which is the essential difference between the I-spread and the Z-spread. This is deemed to be more accurate, because the entire swap curve is taken into account rather than just one point on it. In practice, though, as we have seen in the preceding example, there is often little difference between the two spreads.

To reiterate, then, using the correct Z-spread, the sum of the bond's discounted cash flows will be equal to the current price of the bond.

We illustrate the Z-spread calculation in Figure 45.1. This is done using a hypothetical bond, the XYZ pic 5% of June 2008, a three-year bond at the time of the calculation. Market rates for swaps, Treasury and CDS are also shown. We require the spread over the swaps curve that equates the present values of the cash flows to the current market price. The cash flows are discounted using the appropriate swap rate for each cash flow maturity. With a bond yield of 5.635%, we see that the I-spread is 43.5 basis points, while the Z-spread is 19.4 basis points. In practice, the difference between these two spreads is rarely this large.

We also show the Excel formula in Figure 45.1. This shows how the Z-spread is calculated; for ease of illustration, we have assumed that the calculation takes place for value on a coupon date, so that we have precisely an even period to maturity.

Credit default swaps provide an efficient means of pricing pure credit and, by definition, are a measure of the credit risk of a specific reference entity or reference asset. Asset swaps are well established in the market and are used both to transform the cash flow structure of a corporate bond and to hedge against interest rate risk of a holding in such a bond. As asset swaps are priced at a spread over LIBOR, with LIBOR representing interbank risk, the asset swap spread represents in theory the credit risk of the asset swap name. By the same token, using the no-arbitrage principal, it can be shown that the price of a CDS for a specific reference name should equate the asset swap spread for the same name. However, a number of factors, both structural and operational, combine to make CDSs trade at a different level to asset swaps. This difference in spread is known as the credit default swap basis and can be either positive (the credit default swap trading above the asset swap level) or negative (trading below the asset swap).

At the inception of the market, credit derivatives were valued using the asset swap pricing technique. We will explain shortly why this approach is no longer used. However, let us first consider the theoretical reason why they should be priced using this approach.

A par asset swap typically combines the sale of an asset such as a fixed-rate corporate bond to a counterparty, at par and with no interest accrued, with an interest rate swap. The coupon on the bond is paid in return for LIBOR, plus a spread, if necessary. This spread is the asset swap spread and is the price of the asset swap. In effect, the asset swap allows market participants that pay LIBOR-based funding to receive the asset swap spread. This spread is a function of the credit risk of the underlying bond asset, which is why it could be viewed as equivalent to the price payable on a credit default swap written on that asset.

The generic pricing is given by

where

| Ya = asset swap spread |

| Yb = asset spread over the benchmark |

| ir = interest rate swap spread |

The asset spread over the benchmark is simply the bond (asset) redemption yield over that of the government benchmark. The interest rate swap spread reflects the cost involved in converting fixed-coupon benchmark bonds into a floating-rate coupon during the life of the asset (or default swap) and is based on the swap rate for that maturity.

The theoretical basis for deriving a default swap price from the asset swap rate can be illustrated by looking at a basis-type trade involving a cash market reference asset (bond) and a default swap written on this bond. This is similar in concept to the risk-neutral or no-arbitrage concept used in derivatives pricing. The theoretical trade involves:

A long position in the cash market floating-rate note (FRN) priced at par, and which pays a coupon of LIBOR + X basis points.

A long position (bought protection) in a default swap written on the same FRN, of identical term-to-maturity and at a cost of Y basis points.

The buyer of the bond is able to fund the position at LIBOR. In other words, the bondholder has the following net cash flow:

or X — Y basis points.

In the event of default, the bond is delivered to the protection seller in return for payment of par, enabling the bondholder to close out the funding position. During the term of the trade, the bondholder has earned X – Y basis points while assuming no credit risk. For the trade to meet the no-arbitrage condition, we must have X = Y. If X ≠ y, the investor would be able to establish the position and generate a risk-free profit.

This is a logically tenable argument as well as a reasonable assumption. The default risk of the cash bondholder is identical in theory to that of the default seller. In the next section we illustrate an asset swap pricing example, before looking at why in practice there exist differences in pricing between default swaps and cash market reference assets.

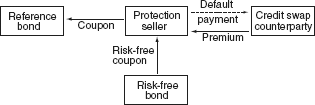

XYZ pic is a Baa2-rated corporate. The seven-year asset swap for this entity is currently trading at 93 basis points; the underlying seven-year bond is hedged by an interest rate swap with an Aa2 rated bank. The risk-free rate for floating-rate bonds is London Interbank Bid Rate (LIBID) minus 12.5 basis points (assume the bid-offer spread is 6 basis points). This suggests that the credit spread for XYZ pic is 111.5 basis points. The credit spread is the return required by an investor for holding the credit of XYZ pic. The protection seller is conceptually long the asset, and so would short the asset to hedge its position. This is illustrated in Figure 45.2. The price charged for the default swap is the price of shorting the asset, which works out as 111.5 basis points each year.

Therefore, we can price a credit default written on XYZ pic as the present value of 111.5 basis points for seven years, discounted at the interest rate swap rate of 5.875%. This computes to a credit default swap price of 6.25%.

| Reference XYZ pic |

| Term Seven years |

| Interest rate swap rate 5.875% |

| Asset swap LIBOR plus 93 bps |

Default swap pricing:

| Benchmark rate LIBID minus 12.5 bps |

| Margin 6 bps |

| Credit default swap 111.5 bps |

| Default swap price 6.252% |

A number of factors observed in the market serve to make the price of credit risk that has been established synthetically using default swaps to differ from its price as traded in the cash market. In fact, identifying (or predicting) such differences gives rise to arbitrage opportunities that may be exploited by basis trading in the cash and derivative markets. These factors include the following:

Bond identity—the bondholder is aware of the exact issue that they are holding in the event of default; however, CDS sellers may receive potentially any bond from a basket of deliverable instruments that rank pari passu with the cash asset; this is the delivery option afforded the long swap holder.

The borrowing rate for a cash bond in the repo market may differ from LIBOR if the bond is to any extent special; this does not impact the CDS price, which is fixed at inception.

Certain bonds rated AAA (such as U.S. agency securities) sometimes trade below LIBOR in the asset swap market; however, a bank writing protection on such a bond will expect a premium (positive spread over LIBOR) for selling protection on the bond.

Depending on the precise reference credit, the credit default swap may be more liquid than the cash bond, resulting in a lower default swap price, or less liquid than the bond, resulting in a higher price.

CDSs may be required to pay out on credit events that are technical defaults, and not the full default that impacts a cash bondholder; protection sellers may demand a premium for this additional risk.

The default swap buyer is exposed to counterparty risk during the term of the trade, unlike the cash bondholder.

An issuance of new bonds by the same reference name may increase demand for credit protection, resulting in a higher CDS price.

For these and other reasons, the CDS price often differs from the cash market price for the same asset. Therefore, banks are increasingly turning to credit pricing models, based on the same models used to price interest rate derivatives, when pricing credit derivatives.

The difference between the CDS price and the asset swap spread can be observed for any number of corporate credits across all market sectors. This suggests that middle-office staff and risk managers that use the asset swap technique to independently value default swap books are at risk of obtaining values that differ from those in the market. This is an important issue for credit derivative market-making banks.

To reiterate then, the CDS basis is the CDS spread minus the asset swap spread. Alternatively, it can be the CDS spread minus the Z-spread. So the basis is given by

where D is the CDS price. Where D - CashSpread < 0 it is a positive basis, the opposite is a negative basis. There is no one accepted measure of CashSpread; practitioners generally use either the I-spread, asset swap spread or Z-spread. The only rule is to use the same measure consistently when conducting relative value analysis. Further observations on the efficacy of using each method are given in Choudhry (2006). Measuring the basis becomes more important when used in formulating arbitrage strategy. Changes in the basis give rise to arbitrage opportunities between the cash and synthetic markets, which can be exploited via a negative basis trade (buying the reference name cash bond and buying protection in CDS) or positive basis trade (selling the bond and selling protection). This is discussed in greater detail in Choudhry (2006).

A wide range of factors drive the basis. The existence of a non-zero basis has implications for investment strategy. For instance, when the basis is negative investors may prefer to hold the cash bond, whereas if for liquidity, supply, or other reasons the basis is positive, the investor may wish to hold the asset synthetically by selling protection using a CDS. Another approach is to arbitrage between the cash and synthetic markets, in the case of a negative basis by buying the cash bond and shorting it synthetically by buying protection in the CDS market. Investors have a range of spreads to use when performing their relative value analysis.

Investors use bond spread analysis to determine the relative value of a bond compared to a benchmark bond or yield curve. The spread is measured in basis points and can be used to ascertain if the expected return from the bond is sufficient compensation for the risk profile it represents. To calculate the bond spread, we can use one of four measures. These measures are the interpolated spread over the benchmark government bond yield, the interpolated spread over the interest rate swap curve, the asset swap spread, and the Z-spread.

The development of a liquid market in credit default swaps means that there is now a yield measure for both the cash market and the synthetic market. The price of a CDS written on a specific reference name is another measure of its relative value. The difference between the cash market yield, given by any spread measure, and the synthetic price is the credit default swap basis.

Andritzky, J., and Singh, M. (2007). Recovery value effect on CDS during distress. Euromoney Structured Credit Products Handbook 2007/08 (pp. 69-77). London: Euromoney Publications.

Choudhry, M., Joannas, D., Pienaar, R., and Pereira, R. (2001). Capital Market Instruments: Analysis and Valuation. London: FT Prentice Hall.

Choudhry, M. (2004). Structured Credit Products: Credit Derivatives and Synthetic Securitisation. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons.

Choudhry, M. (2006). The Credit Default Swap Basis. Princeton, NJ: Bloomberg Press.

Leibowitz, M., and Homer, S. (2004). Inside the Yield Book. Princeton, NJ: Bloomberg Press.

Martellini, L., and Priaulet, P. (2004). Fixed Income Securities. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Miller, T. (2007). Introduction to Option-Adjusted Spread Analysis, revised and expanded 3rd edition of the OAS Classic by Tom Windas. Princeton, NJ: Bloomberg Press.