JAMES MANZI, CFA

Consultant

DIANA BEREZINA

Associate Director, Fitch Ratings

MARK ADELSON

Principal, Adelson & Jacob Consulting, LLC

Abstract: Commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBSs) are a type of fixed income investment backed by commercial loans. They can be appealing to investors because they generally offer high credit quality, a reasonable degree of credit stability, cash-flow stability, and low-spread volatility. Choosing a particular CMBS investment involves careful consideration of the characteristics of the underlying commercial loans, bond structure, risk appetite, and typical deal features.

Keywords: commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBSs), commercial loans, CMBS bond structure, CMBS deal features, prepayment penalties, defeasance, yield maintenance

This chapter is intended to provide an overview of the commercial-mortgage backed securities (CMBSs) market and the tools to choose between different CMBS investments based on relative value considerations, risk characteristics, and nuances in bond structure.

CMBSs are backed by commercial mortgage loans. That is, the underlying mortgage loans are secured by commercial, rather than residential, real estate. In contrast to residential mortgage loans, most commercial mortgage loans in the United States do not allow for unrestricted prepayments by the borrowers. Accordingly, a key distinction between CMBS and residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBSs) is that CMBS embody little or no prepayment risk.

A typical CMBS is a "pass-through" security that represents partial ownership of an underlying pool of commercial mortgage loans. An investor who owns the CMBS is entitled to receive collections of interest and principal on the loans. In CMBS jargon, the payments on the loans are "passed through" to the investors. However, a small portion of the interest collections is not passed through. Instead, it is used to cover expenses of the deal. Thus, a CMBS has a "pass-through rate," which is the net rate at which investors receive interest on the balance of the mortgage loans backing the security.

Unlike Treasury securities or regular corporate bonds, a typical CMBS is an amortizing security. That is, a typical CMBS returns principal to investors incrementally during its life. Monthly distributions to investors ordinarily include both interest and principal. Accordingly, for purposes of pricing CMBSs, market participants frequently use a security's weighted-average life (WAL) instead of its final maturity.

Every CMBS has at least one servicer. A servicer is a company that collects payments from borrowers and handles the administrative task of aggregating the collected funds and transmitting the funds to a deal's trustee for distribution to investors. Naturally, the servicer receives a fee for its services. In most CMBSs, the fees to the servicer consume all or nearly all of the difference between the interest rate on the mortgage loans and the pass-through rate on the security. Many CMBSs have more than one servicer. In such a case, a primary servicer handles routine servicing functions and a "special servicer" takes over on loans that become seriously delinquent.

Unlike most residential MBSs, most CMBSs do not carry guarantees from the U.S. government or from government-sponsored enerprises (GSEs). Accordingly, a typical CMBS transaction uses "credit tranching" as a form of credit enhancement to counterbalance the risk of defaults and losses on the underlying loans. Credit tranching creates multiple classes (or tranches) of securities, each of which has a different seniority relative to the others. Senior classes receive protection from junior classes that bear amplified exposure to credit risk. Rating agencies measure the credit strength of a transaction's different tranches and assign ratings accordingly.

Finally, a major distinction between CMBS and RMBS deals is the role of the buyers of the junior (non-investment-grade) bond classes. In a CMBS, no deal is done without first finding the buyers for the junior classes. The potential buyers first review the proposed pool, and may exclude loans that they do not like. This provides an extra layer of security for the senior buyers, particularly because the buyers of the junior classes tend to be real estate experts. For their extra credit work, the junior buyers generally seek yields in the range of 10% to 15%, or sometimes more, depending on the quality of the underlying collateral.

The most typical commercial mortgage is a nonrecourse, fixed-rate loan with a 7- to 10-year balloon payment, although shorter maturity loans, such as 5-year balloons, have gained in popularity as well. A typical loan provides for partial amortization prior to the balloon date on a schedule corresponding to full amortization over a period of 25 to 30 years. However, in periods of increased competition among lenders, it is not uncommon to see loans offered with interest-only (IO) periods, sometimes for the entire term of the loan (to the balloon date). For example, almost three-fourths of the loans securitized to create CMBS during 2006 had at least a partial IO period. Since these loans do not amortize during the IO period, their inclusion in CMBS pools increases the risk that a borrower will not be able to make the balloon payment. Negatively amortizing loans are rare (except with construction loans). Additionally, there have been loans where the amortization rate is accelerated as well as some loans with payment schedules designed to match lease payments.

Cash flows arising from a typical commercial mortgage include monthly interest, principal, and possibly prepayment penalties, and default or extension penalties. CMBS deals have mechanisms to allocate all such cash flows to the respective bond classes. Loans in CMBS deals have ranged in size from just about $1 million to several hundred million dollars. As for the deals themselves, almost all recently issued, fixed-rate deals have combined large loans and small loans and are typically referred to as "conduit/fusion deals." Transaction sizes have varied between a few hundred million dollars to several billion dollars, and generally include several hundred separate loans/properties.

Most commercial mortgages are fixed rate, although there are floating-rate mortgages as well. Generally, fixed-and floating-rate mortgages are not mixed in the same pool. To the extent that there is a great disparity in the interest rates among the loans in a pool, the weighted-average coupon (WAC) can vary considerably over time. The difference in coupon at the inception of the deal can arise due to the loans having been originated over time as interest rates have changed, or due to varying degrees of risk of the loans. Over the life of the deal, even more dispersion can occur. This is true even if the amortization or principal occurs as expected. It gets more complicated if there are unanticipated principal paydowns due to either prepayments, defaults, or extensions.

Table 34.1. Typical Conduit/Fusion Deal(JPMCC 2006-LDP6)

Class | Size($MM) | Rating | Credit Support(%) | Average Life(yrs) | Coupon | Principal Window (Months from Issue) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A1 | 59.9 | Aaa | 30.00 | 3.01 | 5.160 | 1-58 | Super-duper senior |

A2 | 155.9 | Aaa | 30.00 | 4.90 | 5.379 | 59-61 | Super-duper senior |

A3B | 55.7 | Aaa | 30.00 | 7.14 | 5.559 | 81-96 | Super-duper senior |

A3FL | 100.0 | Aaa | 30.00 | 6.71 | L+16 | 81-81 | Floatingrate |

A4 | 819.3 | Aaa | 30.00 | 9.85 | 5.475 | 110-120 | Super-duper senior |

ASB | 103.7 | Aaa | 30.00 | 7.08 | 5.490 | 58-110 | Amortization bond |

A1A | 205.0 | Aaa | 30.00 | 8.28 | 5.471 | 1-120 | Multifamily carve-out (FNMA and Freddie Mac only) |

AM | 214.2 | Aaa | 20.00 | 9.96 | 5.525 | 120-120 | Mezzanine super senior |

AJ | 163.3 | Aaa | 12.38 | 9.96 | 5.565 | 120-120 | Junior triple-A |

B | 48.2 | Aa2 | 10.13 | 10.02 | 5.702 | > 120 | |

C | 18.7 | Aa3 | 9.25 | 10.04 | 5.722 | >120 | |

D | 34.8 | A2 | 7.63 | 10.04 | 5.775 | >120 | |

E | 21.4 | A3 | 6.63 | 10.04 | 5.775 | >120 | |

F | 29.5 | Baa1 | 5.25 | 10.04 | 5.775 | >120 | |

G | 21.4 | Baa2 | 4.25 | 10.04 | 5.775 | >120 | |

H | 21.4 | Baa3 | 3.25 | 10.04 | 5.775 | >120 | |

J | 10.7 | Ba1 | 2.75 | 10.04 | 5.155 | >120 | "B" piece |

K | 10.7 | Ba2 | 2.25 | 10.04 | 5.155 | >120 | |

L | 5.4 | Ba3 | 2.00 | 10.04 | 5.155 | >120 | |

M | 5.4 | B1 | 1.75 | 10.04 | 5.155 | >120 | |

N | 5.4 | B2 | 1.50 | 10.04 | 5.155 | >120 | |

P | 8.0 | B3 | 1.13 | 10.11 | 5.155 | >120 | |

NR | 24.1 | NR | 0.00 | 12.53 | 5.155 | >120 | |

X1 (Comp) | 2,142.1[a] | Aaa | N/A | 8.58 | 0.040 | IO class | |

X2 (PAC) | 2,096.7[a] | Aaa | N/A | 5.53 | 0.255 | IO class | |

[a] Signifies notional balance. | |||||||

CMBS use subordination for credit enhancement. Table 34.1 shows the typical structure of a conduit/fusion transaction.

The senior-subordinate structure creates senior and junior interests in the underlying asset pool. In Table 34.1 each tranche, from AM down to NR provides protection to (that is, is subordinate to) each other tranche listed above it and receives protection from (that is, is senior to) each other tranche listed below it. The structure requires that all principal payments, both scheduled and from recoveries on defaulted loans, be used to retire the most senior outstanding bond. In addition, the structure allocates losses to the most junior outstanding classes. In a typical deal, most of the bond classes have fixed coupons, but the IO classes (XI and X2) and a few of the bonds near the bottom of the capital structure are WAC bonds. Essentially, a WAC bond pays a varying coupon over time, based on the weighted-average interest rate of the loans in the pool. As the balances on the loans change, their relative weightings change, which results in a changing coupon on the WAC bond. The creation of WAC bonds generally is necessary (for a greater number/amount of bonds on the capital structure) when rates increase sharply during the loan aggregation phase of a CMBS deal.

Due to the generally positive credit performance of CMBSs dating from the early 1990s to the mid-2000s, the rating agencies steadily lowered subordination levels. However, some investors believed that the credit enhancement levels had dropped too low. In response to investor worries about falling subordination levels in CMBS conduit/fusion deals, dealers started to break up the triple-A-rated class into super-senior, "mezzanine," and "junior" parts. In the structure shown in Table 34.1, classes Al, A2, A3B, A3FL, A4, ASB, and A1A have 30% credit support from subordination and are called "super-duper seniors." Class AM is the mezzanine triple-A-rated tranche. It has 20% credit enhancement from subordination and is called the "super-senior" class. Class AJ is the "junior," or "mezzanine," triple-A-rated tranche and has approximately 12.4% credit enhancement. With this structure, investors who are worried about future CMBS credit performance (e.g., the effects of another prolonged real estate recession like that of the early 1990s) can buy bonds with more protection. Those who are comfortable with the current triple-A subordination levels and the added extension risk (relative to the super-senior AM and the super-duper senior class), can invest in the mezzanine or junior triple-A classes, and receive a small amount of incremental compensation in the form of a slightly wider spread on their bonds.

CMBS spread levels are highly dependent on the balance of supply and demand within the sector, as well as spreads on competing investments, such as residential MBS and corporate bonds. Bonds from seasoned deals may trade with varying spreads depending on the credit performance of the underlying collateral. Information on the CMBS market has become readily available to investors, contributing greatly to the market's strong liquidity. Organizations such as Trepp, Intex, and Bloomberg collect extensive data on the secondary market while publications such as Commercial Mortgage Alert provide updates on issuance as well as information on the pipeline of upcoming deals (as far as three months ahead). All other things being equal, when the market is flooded with new deals or when the pipeline projects heavy issuance, spreads tend to widen. However, at times when there is a lull in issuance and investors do not have many deals to choose from, spreads generally tighten. Movements in spreads of other investment products, namely corporate bonds and RMBSs, also tend to drive CMBS spreads. This is true predominantly for the top of the capital structure (classes rated single-A or higher) as investors may cross over between these products in search of higher yield.

Deal Selection

With similar vintage deals generally pricing within a few basis points of each other at the top of the capital structure and offering similar credit enhancement levels, how do investors decide which deal or tranche to buy? Thanks to the increasing transparency of the CMBS market, investors who are willing to carefully scrutinize deals have access to extensive information, such as rating agency presale reports. Naturally, investors who buy riskier tranches (that is, lower in the capital structure) typically spend far more time analyzing a collateral pool than those who invest in the senior triple-A-rated tranches that have 30% credit support. Some deal features to focus on are reviewed below.

Stressed Loan-to-Value Ratio and Debt Service Coverage Ratio Each rating agency calculates a "stressed" loan-to-value ratio (LTV) and stressed debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) for each deal that it rates using its own definition of sustainable cash flow and consistent capitalization rates. This is useful in discerning how aggressive or conservative the loan originator's underwriting may have been even if the reported (underwritten) LTVs are all around 70% to 75%, and the reported DSCR is around 1.3 to 1.5 times.

Interest-Only Loans An IO loan presents greater risk than an amortizing loan because the full original principal amount of the loan is due on the balloon date—there is no amortization during the life of the loan to reduce the balloon risk. In a deal, the greater the share of Io loans, the greater the exposure to balloon risk.

Top 10 Many investors are weary of "lumpy" deals, where several big loans make up a significant portion of the pool. The inherent risk of such deals is that the deterioration of just a few large loans can jeopardize the entire deal.

Property Mix As the real estate market undergoes cycles, different property types tend to encounter difficult periods. For example, during the housing boom of the mid-2000s, the multifamily sector suffered high delinquency rates and their respective portion of CMBS collateral pools declined. Market size can also be important, as deals with concentrations of collateral in economically booming large metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs) are likely to perform better than those backed by properties in economically troubled secondary or tertiary markets.

Since the inception of the market in the early mid-1990s, the "big 5" property types—office, retail, multi-family, industrial, and hotels—made up an overwhelming majority of CMBS pools on a weighted-average basis. While the performance of the individual property types is interrelated and subject to "macro" risk variables such as interest rates and inflation, each sector also has certain idiosyncratic risks. For example, job growth, outsourcing, and the growth of "telecommuting" are factors usually associated with office properties, while high levels of consumer spending and disposable income, in part due to home price appreciation, were linked with strength in the retail and lodging sectors during the early mid-2000s. Typically, to judge the health of a particular market and property type combination, CMBS professionals look at recent trends in supply (completions/construction), demand (absorption), effective rent (property income), and vacancy (occupancy).

In addition, trends in capitalization rates, and the recent levels of sales/transactions (both number and dollar value) may be used in conjunction with the previously mentioned "fundamentals" to measure property values and whether they are forecasted to appreciate or depreciate.

One of the main advantages to investing in conduit/fusion CMBSs is the diversity of the collateral pools. As noted above, pools backing an average deal may contain several hundred individual loans, some of which may be multi-property loans. Additionally, there are typically seven or eight different property types represented in a transaction, though office, multifamily, and retail tend to make up the lion's share of the collateral. While this "concentration" may seem worrisome at first, several rating agency loss and default studies have shown that loss severities in the core property types (multifamily, retail, industrial, and office) tend to be lower than those of noncore property types. In addition, there are several other types and measures of diversity related to CMBS transactions.

Diversification by geography protects against downturns in specific real estate markets, and the fact that different markets may be at different phases of their real estate cycles at the same time. A typical CMBS transaction contains loans from most of the 50 states, with a large majority of the collateral located in the top 50 MSAs by population. Thus, it should come as no surprise that roughly 25% of the domestic CMBS market is made up of loans secured by properties in New York and California.

While this apparent lack of diversity may seem to be a cause for concern, as with the concentration in a limited number of property types, based on historical performance, it is also likely a benefit to investors. Rating agency studies have shown that defaulted loans in smaller secondary and tertiary markets generally experience higher loss severities than defaulted loans in larger, primary markets. We believe that the amount of available land on which to build is one of the primary reasons for this phenomenon.

In addition to geographic and property type diversity, the rating agencies (and the rest of the market) typically utilize Moody's Herfindahl score and the top 10 percentage to measure the concentration risk (by loan balance) in a collateral pool. Moody's Herfindahl score measures a pool's lumpiness and is calculated as:

where n is the number of assets, pi is the principal balance of each asset, and P is the aggregate principal balance. A credit-neutral score is 100, while scores, on average, have ranged between 40 and 140 over the late 1990s to mid-2000s. Concentration measures are of particular interest to buyers at the lower end of the capital structure, as lower-rated tranches in transactions with lumpy collateral are more exposed to the default of a relatively smaller number of large loans.

One crucial difference between residential and commercial mortgages, which tends to give CMBSs better cash flow stability and positive convexity, is strict rules regarding prepayments. Most commercial mortgages prohibit or severely limit voluntary prepayments through a lockout period, combined with defeasance and yield maintenance provisions. In other words, if the loan does not contain a lockout feature, it will likely have features designed to discourage the borrower from making a prepayment and to compensate the lender in the event of a prepayment. Often, the prohibitions are for the majority of the life of a loan, with a small open period lasting three to six months before the balloon date. The short open period is designed to give the borrower the opportunity to refinance the balloon. By far, the most common feature discouraging prepayment in most conduit/fusion loans is defeasance. A small percentage of yield maintenance provisions are present in the remainder. The two prepayment deterrents contain important differences regarding the amount and timing of the cash flows.

Defeasance

Under the defeasance approach, the borrower is required to purchase U.S. Treasury securities whose cash flows equal or exceed the remaining payments of the mortgage loan. In this case, the cash flow to securities backing the loan remains identical to what it would have been without the defeasance. As stated before, defeasance has become the most popular form of prepayment protection because of the virtual elimination of credit risk that it affords the investor, as well as the simplicity of the structure. Also attractive to lenders is the fact that the cost of defeasance to the borrower is, on average, quite high—which strongly discourages prepayments.

Yield Maintenance

The concept of yield maintenance is to make the lender indifferent to the prepayment of a loan with a cash premium equal to the future value of the loan's cash flows. Unlike defeasance, yield maintenance provisions require a one-time, lump-sum cash payment, rather than replication of the cash flows of the mortgage loan. As such, issues may arise over the correct discount rate to be applied in calculating the lump-sum payment. Additionally, each deal's structure dictates the allocation rules regarding the penalty cash flows. The allocation of these penalties among the bond classes can vary considerably between deals. The specifics of the allocation can have a significant impact on the performance of the different bond classes. In a multiclass deal, while the penalty still serves as a deterrent to the borrower prepaying, it may not be sufficient to fully compensate all of the bonds within the transaction.

In the mid-1990s a variation to the balloon loan was developed, known as an ARD (anticipated repayment date) loan. The ARD is similar in many respects to a balloon date, except for one important difference. Failure to fully repay principal on a loan's balloon date is an event of default. In contrast, failure to retire a loan on its ARD is not an event of default. The borrower could keep on paying scheduled principal and interest after the ARD. However, in order to motivate the borrower to pay off the loan on the ARD, the loan's interest rate would rise sharply and all excess cash flow (above the debt service, insurance, taxes, funding of reserves, etc.) would be applied to pay down principal (a situation known as "hyperamortization"). From a credit perspective, the ARD feature alleviated the pressure caused by the required balloon payment, with some protection against interest-related balloon extension. During the mid-2000s, some of these protections against nonpayment at the ARD had been relaxed, but a full discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter.

When a loan meets certain criteria for being troubled, such as being delinquent for 120 days or experiencing foreclosure of its collateral (that is, becoming real estate owned or REO), it may trigger an appraisal reduction event within a CMBS transaction. In such a case, the principal balance of the first loss class(es) is written down in anticipation of a future loss, effectively reallocating the interest cash flow to the seniormost tranche. Thus, the senior bondholders are better protected against a scenario where a troubled property undergoes a long, drawn-out, workout before the loan can be fully resolved.

Appraisal reductions are interesting from the standpoint of derivatives. An appraisal reduction is an actual writedown of a security. The use of appraisal reductions in the CMBS sector arguably eliminates the need for implied write-downs as used in the standard documentation of credit default swaps (CDSs) on CMBS.

The responsibilities of the servicer and special servicer in a CMBS deal are as follows. The servicer is responsible for supervising the regular cash flow aspects of the loan. It keeps track of the reserves, the insurance payments, the tax payments, and similar items. The servicer is also responsible for advancing principal and interest through foreclosure of a loan, for as long as it deems the advances recoverable. A loan is moved to the special servicer only when the borrower is in default, imminent default, or in violation of covenants. The special servicer is charged with the responsibility of working out the loan. Ideally, the special servicer can restore the loan to performing status. The special servicer has the authority to take the loan through the foreclosure process and is supposed to be guided by the principle of maximizing the present value of proceeds from the property. Sometimes, however, conflicts of interest can arise because the special servicer is often the owner of the junior (first-loss) classes.

Consider a potential balloon default as an example, where the special servicer can choose between extending the loan or foreclosing and selling the property. From a credit perspective, the senior class usually views an extension as an adverse event (unless there is little or no subordination left) because the real estate collateral could continue to deteriorate and thereby lessen the proceeds at a subsequent foreclosure. However, from a rate-of-return perspective, the senior bondholder could be better off with the extension in a falling interest rate environment. Conversely, an extension in a rising rate environment would negatively impact the performance of the senior bondholder. All else being equal, we think loan extensions are more likely in a rising-rate environment.

In contrast to a senior bondholder, a junior bondholder may prefer an extension. If the property value has deteriorated to the point where foreclosure proceeds would be less than the loan balance (plus unpaid interest), the junior class would surely suffer a loss. In this case the junior bondholder would prefer that the borrower be granted an extension, to keep the loan cash-flowing. If the property value in foreclosure is large enough to fully pay the junior class, however, the junior bondholder would likely align with the senior bondholder to push for foreclosure as quickly as possible. One would not expect the latter situation to occur often because if foreclosure proceeds would be sufficient to permit a full recovery for both senior and junior bondholders, the borrower might do better to sell the property and pay off the loan.

As noted above, if a securitized commercial mortgage defaults during its term, the servicer is required to advance principal and interest through foreclosure, provided that it deems the advances to be recoverable. This enhances the timeliness of distributions to holders of the securities even when there are interruptions in the inflow of property income. The servicer is compensated with interest on these advances and is first in line to recover advances upon the liquidation of the property. In the case of a prolonged foreclosure, where the servicer continues to advance principal and interest, the proceeds from a sale may not be enough to fully compensate the servicer for his advances, plus interest. The result can be an interest shortfall to the bonds in a deal. Interest shortfalls on subordinate tranches are reasonably common. Interest shortfalls have occurred on CMBS tranches rated triple-A, though such events are very rare.

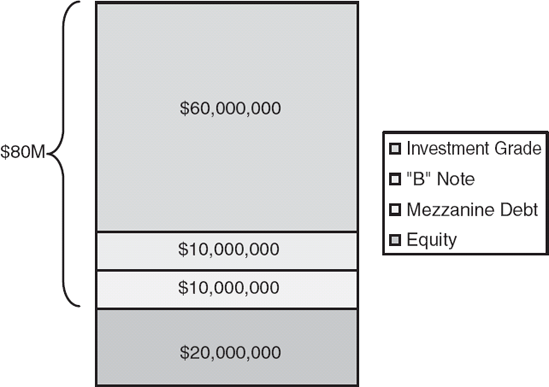

A CMBS loan may be divided into senior and junior interests. Figure 34.1 illustrates a generic $100 million property financed with (1) a $60 million dollar investment grade "A-note," (2) a $10 million "B-note," (3) $10 million in mezzanine debt, and (4) $20 million in hard equity. Typically, only the A-note will be included within a conduit/fusion deal. The B-note ordinarily would not be included in a CMBS trust. However, we have seen cases where both an A-note and its related B-note are securitized within the same CMBS transaction. During the mid-2000s, B-notes and mezzanine debt were popular collateral types for inclusion within commercial real estate (CRE) collateralized debt obligations (CDOs).

In the event of default, the B-note holder's right to principal and interest payments is subordinate to the rights of the holder of the A-note. Also, the A-note holder will generally have greater, if not exclusive, control over any bankruptcy proceedings dealing with the workout of a troubled loan. Typically, for the B-note holder to obtain greater control over the workout of a troubled loan, he will have to exercise the option usually granted the B-note holder of buying out the A-note holder's participation in the loan, at par plus accrued interest. Other important rights that the B-note holder may have include:

The right to hire and fire the special servicer.

The right to cure defaults in order to keep the senior lender from foreclosing (usually, there is a limit to the number of times this right can be exercised).

Approval rights associated with the property budgets, leases, and property managers.

A mezzanine loan is not secured by a lien on the related property. Instead it is a pledge of stock in the special purpose entity that owns the property and that is the borrower on the A-note and on the B-note. In effect, the mezzanine lender is subordinate to the first mortgage (the A-note and the B-note) and senior to the hard equity holder. If the mezzanine loan gets into trouble, the holder cannot foreclose on the property directly. Rather, the mezzanine debt holder can foreclose on the equity interest of the first mortgage borrower, in effect taking over the borrowing entity, and therefore controlling the property in question.

A common feature of older loans is a prohibition on additional debt against the real estate after the inception of the loan. This is important because adding extra debt can immediately raise the leverage against the property and increase the debt service burden. Many recent commercial mortgage loans permit borrowers to take additional debt. It is now quite common to see CMBS deals in which as much as 40% (or more!) of the underlying loan pool (by principal balance) allows additional debt. Although most such loans require mitigating factors—the loan must meet certain tests, such as maintaining a specified combined DSCR and combined LTV—this is still a worrisome trend.

In this chapter, we covered general characteristics of CMBSs and the commercial loans underlying the transactions, as well as some of the nuances that an experienced CMBS market participant would consider before making an investment. It is clear that choosing a particular CMBS investment involves careful evaluation of the characteristics of the underlying commercial loans, the structure of the deal, the investor's risk appetite, and relative value, among many other important considerations!

DeMichele, J. E, Adams, W. J., and Hewlett, D. C. (2002). Commercial mortgage-backed securities. In E J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Financial Instruments (pp. 399–22), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, E J. (ed.) (2001). Investing in Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, E J., and Jacob, D. P. (eds.) (1999). The Handbook of Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities, 2nd edition. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Jacob, D. P., and Fabozzi, E J. (2003). The impact of structuring on CMBS bond class performance. Journal of Portfolio Management (Special Real Estate Issue): 76–86.

Leffler, P., Malysa, J., Story, J., and Merrick, S. S. (2006). Cash-flow CDOs for CMBS investors. In E J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Mortgage Backed Securities (pp. 1209–1216), New York: McGraw Hill.

Obazee, P. O., and Hewlett, D. C. (2006a). CMBS collateral performance: Measures and valuations. In E J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Mortgage Backed Securities (pp. 1187–1198), New York: McGraw Hill.

Obazee, P. O. and Hewlett, D. C. (2006b). Value and sensitivity of CMBS IOs. In E J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Mortgage Backed Securities (pp. 1199–1208). New York: McGraw Hill.

Sanders, A. B. (2005). Commercial mortgage-backed securities. In E J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities (pp. 615–628). New York: McGraw Hill.