HENRY G. JARECKL MD

Chairman, The Falconwood Corporation

TERRENCE F. MARTELL, PhD

Saxe Distinguished Professor of Finance, Zicklin School of Business, Baruch College/CUNY

Abstract: Tangible commodities represent an asset class separate from stocks and bonds. Historical returns of a diversified portfolio of commodities are as high as those of equities and are not correlated with them. Thus, the inclusion of a modest allocation of commodities to a typical stock and bond portfolio provides a diversification benefit, reducing the overall risk of that portfolio without reducing the returns. The most efficient way to get consistent exposure to commodities for diversification is by an investment in a long-only commodity fund.

Keywords: diversification, asset allocation, tangible commodities, futures, volatility, risk-adjusted return, investment portfolio, mean-variance optimization, asset class, efficient frontier, correlation, Tangible Asset Program® (TAP®)

Diversifying to reduce the risk of ruin is not a new concept. "Don't put all your eggs in one basket" is age-old wisdom. What lies behind this adage? And how do commodities relate to diversification?

This chapter will help you understand why commodities, when added to a stock and bond portfolio in reasonable quantities, tend to reduce the overall risk of the portfolio without reducing the overall return on the portfolio. The chapter will also explain what a long-only commodity fund is and why long-only commodity funds are the most appropriate way to gain commodity exposure.

Investors have traditionally owned stocks for appreciation and bonds for stability, but the idea of having commodities in one's investment portfolio is relatively new. Only gold, of all the commodities, has had a long history as an investment. Other tangible commodities such as cattle, copper, and cotton were not considered for investment purposes until the early 1990s.

Before that, theoreticians, investment institutions, and their advisers—who had been introduced to financial futures trading on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in the early 1970s—knew little about tangible commodities, and the little that they thought they knew was that commodities were far more volatile than stocks and that most commodity investors went broke.

It was probably true that most commodity investors lost money, but this was not due to any inherent danger but to the fact that commodity futures can be bought on so little margin that the average investor's exposure is 10 or even 20 times as great as the limited amount of margin money he or she deposits. As a result, even small price changes lead to large fluctuations in profit and loss; and it is this observation that has led people to believe that the dollar values of the commodities themselves were very volatile. This is not true, however. When theoreticians actually measured commodity price volatility, they found that tangible commodities were less volatile than equities.

This fact, coupled with tangible commodities' lack of correlation with both equities and bonds, prompted theoreticians to look at them as a unique asset class that could provide a substantial diversification benefit when added to an investment portfolio.

Traditionally, the commodity market was composed of "hedgers," who used the market to reduce their risk, and "speculators," who tried to profit from price movement. As a result of the application of asset allocation principles to commodities, we have seen the development of a third major market participant, the commodity investor. Unlike the speculator who makes his or her own buy and sell decisions or is guided to them by his broker, the commodity investor typically employs a third-party fund manager to make the decisions.

As a consequence of the rise in energy and metals prices, of the prospect for further increases due to the long-term economic growth of the developing Chinese and Indian economies, and of the fear of U.S. inflation induced by expanding budget deficits, more and more people—and institutions as well—began investing in commodities. Many of them have come to include a diversified basket of tangible commodities in their portfolios.

They believe, and we agree, that it makes sense to put commodities into an investment portfolio because:

Their historical returns and volatilities are similar to those of equities.

Their returns are not correlated with those of equities or of bonds.

Over almost any long period since 1960, they improve the risk-adjusted return and lower the risk of a large loss of most "equities-plus-bonds" mixes to which they are added.

They provide protection against political crises and natural disasters.

They provide significant protection against inflation.

We will review each of these characteristics of tangible commodities, using the 20-year returns of an actual commodity investment portfolio called TAP® as aproxy for commodities. TAP (for Tangible Asset Program®) was created in 1987 by Henry Jarecki as the commodity portion of a diversified investment portfolio, in accordance with the asset allocation principles of Markowitz portfolio theory.

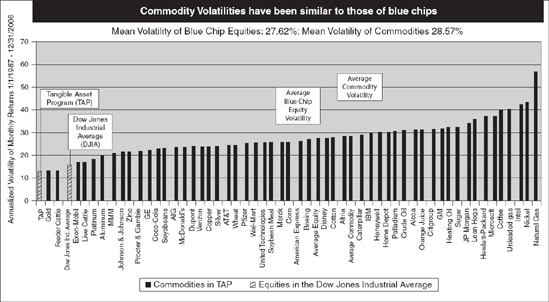

TAP's returns since its inception in January 1987 through March of 2007 are comparable to those of equities. TAP's commodities have provided a return of 11.6%; the S&P 500 11.7%. More important, as Figure 56.1 reports, commodities have had a lower standard deviation—12.6% compared to 15.2% for equities—despite the fact that there are nearly 28 times as many objects in the S&P 500 index as in the TAP commodities portfolio. (The more different objects there are in any pool, the lower its volatility is likely to be. The 500-member S&P should logically have more internal offsets and thus a lower volatility than the 18-member pool of TAP's exchange-traded commodities.) The higher return and lower volatility significantly enhanced TAP's risk-adjusted return. TAP's Sharpe ratio, a measure of return/risk utility, was 0.54—about as high as the Sharpe ratio of bonds—and significantly higher than the 0.45 Sharpe ratio of equities over the same period.

The TAP portfolio has the lowest average volatility (12.6%) of any object displayed in Figure 56.1, followed by gold and feeder cattle, and only then by the DJIA (15.2%). The figure also shows that individual commodities are no more volatile than individual equities. The average commodity volatility (28.6%) is marginally higher than the average volatility of the 30 blue-chip stocks (27.6%).

Commodities help to diversify a portfolio because their returns are not correlated with those of other asset classes. Indeed, they have had a slightly negative correlation with U.S. equities (—0.18), foreign equities (—0.11), and U.S. bonds (—0.13). The lack of correlation between asset classes that have positive returns reduces the volatility (standard deviation) of returns and produces improved risk-adjusted returns. Commodities' lack of correlation with equities and bonds also confers downside protection during events that have a negative impact on stock and bond returns, such as natural disasters, geopolitical uncertainty, or times of rapidly increasing energy prices. The low correlation of commodities with equities can perhaps be explained by thinking of equities as anticipatory assets in the sense that investors value them based on their future cash flows. Commodities, however, are priced based on supply and demand; their prices reflect an equilibrium based on production and consumption rates and the adequacy of inventories. Are people living well, buying a lot of things, and thus making rarer and more expensive the commodities of which the things are made? Or are they retrenching and not buying things? Where current inventory and future production appear inadequate to meet current and future needs, current prices rise to balance supply and demand and to induce producers to expand future production by allocating investment capital.

Figure 56.1. Comparison of Commodity and Equity Volatility: January 1987 to December 2006 Source: Gresham Investment Management LLC

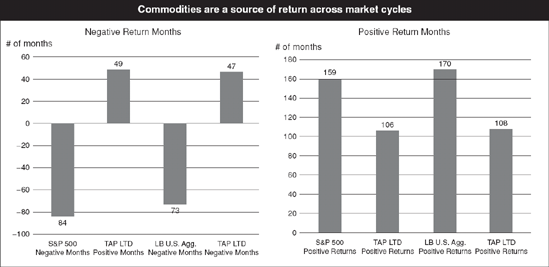

Commodities can for these reasons be a source of return across market cycles. As Figure 56.2 shows, commodity futures have historically achieved positive returns not only when stocks and bonds went up, but also when they went down.

There is a sound economic reason for the countercyclical character of stock prices and commodity prices. It relates to the business cycle. Equity returns will, according to this view, be highest at the start of an economic expansion when expectations of future cash flows are running high, whereas commodity returns are highest near the end of an economic expansion when consumption rates are high, inventories are depleted, and new production has not yet come on stream. Returns of commodities and equities thus have somewhat alternating price cycles.

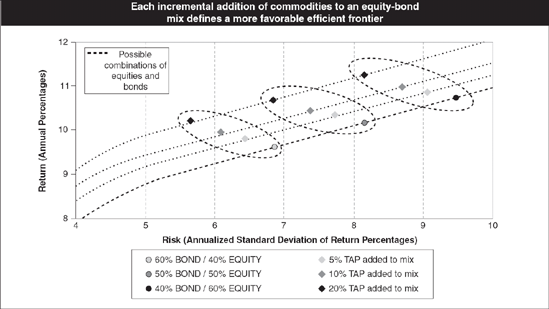

Asset allocators are concerned with improving the overall return/risk profile of their portfolios and with decreasing the possibility of large losses. But, ideally, they would prefer not to sacrifice returns, and that is where commodities come into play From 1987 onward (when TAP was started), an allocation to a diversified basket of long-only tangible commodities has helped to increase a portfolio's total return while decreasing its risk—even if, in order to buy commodities, one had lowered one's equity allocations. The hypothetical benefit of adding commodities to a traditional equities and bonds portfolio is shown in Figure 56.3.

If we look at the efficient frontier of portfolios consisting only of domestic equities and domestic bonds, we can see that, over the 17-year period from 1987 to 2005, adding commodities in various amounts (5, 10, and 20% in Figure 56.3) improved the return/risk profile of whatever equity/bond mix one chooses (40-60, 50-50, or 60-40). In fact, each incremental addition of commodities to the original equity-bond mix defines a more favorable efficient frontier.

As noted above, commodities can protect overall portfolio returns because they have historically shown little or no correlation to the downward moves of stock and bond markets, and they tend to gain in value during events that have a negative impact on stock and bond returns.

During political crises and natural calamities, the correlations of most financial assets—with the possible exception of U.S. Treasury securities—tend to increase. Their prices fall together as investors bail out of assets they perceive as more risky. Commodities, however, offer protection against losses during such times. In addition, large commodity price movements are more often increases than decreases. These relationships are so well known among professionals that it is sometimes said that commodities "fall up."

Figure 56.2. Comparison of Returns: January 1987 to March 2007 Source: Gresham Investment Management LLC.

Figure 56.3. Balanced Portfolio Efficient Frontier with and without Commodities: 1987 to 2005 Source: Gresham Investment Management LLC.

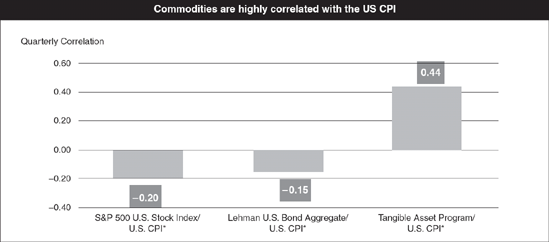

As Figure 56.4 reports, unlike equities and bonds, which are negatively correlated with the U.S. Consumer Price Index, commodities are positively correlated with the CPI (0.44). This is not surprising since commodity prices are a main determinant of the cost of living and thus of inflation. On a shorter-term basis, commodities, denominated in an investor's home currency, tend to perform well when that currency weakens.

What is the best way to get diversified commodity exposure for an investment portfolio? Buying a collection of physical commodities is impractical for most investors because of the difficulties of purchase, transportation, storage, spoilage and shrinkage, and the inability to rebalance. There are only four practical ways to go about obtaining such exposure: investing in natural resource shares or funds, managed futures funds, nondiversified commodity sector funds, and diversified commodity funds and indices.

Natural resource shares or funds. Some investors think they have commodity exposure because they own natural resource stocks. This does not work as well as one might expect, for the value of such stocks is affected by factors other than commodity prices, such as industry competition, management's successful strategy execution, and production-related hedging, all of which affect performance and thus dividends and share prices. There is often little correlation between the price of a commodity producer's shares and the price of the commodity itself. For example, over the period 1990 through 2006, the correlation between American Stock Exchange Oil Company index and the NYMEX Crude Oil contract was 0.31.

Managed futures funds. Some investors hope to obtain exposure to commodities by buying a managed futures (or Commodity Trading Advisor's) fund. While such a fund may or may not provide satisfactory returns, it is not an effective way to get commodity exposure. Most CTA programs involve financial futures strategies, not tangible commodities. And, while CTA returns may not be correlated to equities, they are also not commodity class returns. Even if a CTA includes tangible commodities in a fund, the program may use substantial leverage and may also go short, so an investor will have far more or far less commodity exposure than might have been expected. Finally, a CTA's fees may or may not be reasonable from a trading perspective, but they are high if your goal is adding asset class exposure in commodities.

Some investors have looked to a managed futures fund to supplement a core investment in a diversified commodity fund, thus using the opportunities available to a talented money manager to gain alpha. This "core-plus-satellite" strategy may make sense for those who understand the risks inherent in active management programs.

Nondiversified commodity sector funds. Exchange-traded funds (ETF's) and nonliquid structures: Included in this category are a plethora of old and new investment vehicles such as oil and gas leases, mineral rights, timber, alternative energy plays, single-commodity and single-sector ETFs, funds with a very small number of commodities, and similar structures. Some of these are liquid; some require the investor to give the manager an extended notice period of the desire to withdraw funds (that is, long lock-up periods). By definition, they are all less diversified and therefore can be expected to have a higher volatility than a diversified fund, though they may meet some investors' needs. Because they are not as diversified, they do not provide efficient exposure to the commodity asset class.

Diversified commodity funds and investable indices. The most efficient way to get commodity class exposure is to invest in a rules-based, long-only fund product or private account that invests in liquid tangible futures contracts. Fees will be substantially less than for an actively managed fund, and managers will typically not demand a profit share for providing asset class exposure alone.

The Tangible Asset Program is an example of a long-only commodity fund. The TAP methodology consists of a set of rules for choosing the commodities and the amounts of each one (their relative weights), two factors that are updated annually. The rules are straightforward and transparent and reflect the experience gained from maintaining TAP since 1987. Some of the more important "rules" for TAP include:

To make it possible to buy and sell the commodities without being subject to high transaction costs, TAP is limited to exchange-traded commodity futures contracts.

TAP's managers calculate the dollar value traded of all futures contracts (as a measure of liquidity) and average that number with double the global production value of the underlying commodities (reflecting that real commodity prices are determined in the streets and stores and not on exchange floors).

TAP's managers then select the top three commodities in each of six separate groups.

There is no leverage. If the model calls for a $1 million investment in corn, TAP would go long (buy) corn futures contracts with a face value of $1 million, depositing the margin (approximately 5% of the value of the commodity position or $50,000) and placing the remainder in short-term, low-risk money market instruments like U.S. Treasury bills.

The weight of each commodity and of each group is limited to ensure that the portfolio is truly diversified and not just a tail being wagged by some dominant commodity's dog.

Finally, each commodity's weight is rebalanced whenever price changes cause the initial weighting to get out of line. This results in reducing positions when prices move up and increasing positions when prices move down.

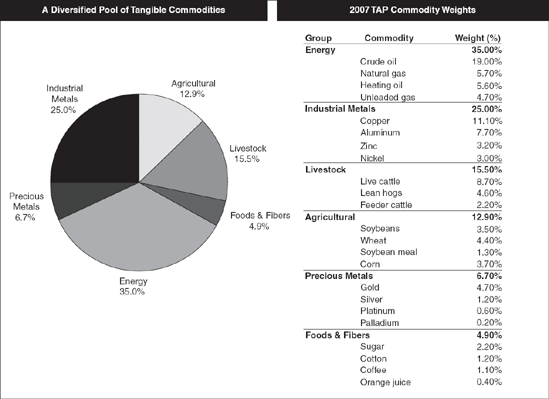

The 2007 composition of TAP is shown in Figure 56.5. There are a total of 18 physical commodities in the portfolio, with no single commodity dominating.

Figure 56.5. TAP Is a Rules-Based, Long-Only, Diversified, Multicommodity Strategy that Was Started in 1987 Source: Gresham Investment Management LLC.

Since the pioneering work in defining the TAP methodology, interest has grown in using tangible commodities for diversifying an investment portfolio, as evidenced by the later creation of the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index (GSCI) and Dow Jones-AIG commodity indices. In recent years there has been significant interest in funds such as TAP, and there is now well in excess of $100 billion invested in such funds.

Can a long-only commodity fund be too diversified? A fund with 30 or 35 commodities is certainly diverse and would be expected to offer the return-smoothing benefits that flow from diversification. However, such a fund would be subject to two other potential problems: a lack of liquidity in the futures contracts the fund must buy and roll; and a lack of replicability/transparency if the futures contracts are traded in foreign time zones and are settled in currencies other than the U.S. dollar. Since tangible futures contracts must be rolled to a forward month prior to delivery, trading volumes must be adequate to support the periodic rolling, or the fund will be penalized with less robust returns. Since there are at most 20 to 25 liquid tangible commodities traded on U.S. and U.K. exchanges that are settled in U.S. dollars, one should be wary of a fund that includes futures contracts or exchanges that may not support rolling.

In this chapter, we have reviewed the case for the inclusion of commodities in a well-diversified investment portfolio. The key components of the arguments are that diversification reduces risk and that the risk-return characteristics of a portfolio of commodities are sufficiently different from other assets so as to comprise a separate asset class.

A diversified commodity portfolio has returns similar to equity returns but with less risk. Moreover—and this is key—the correlation between those returns are low. Thus, the inclusion of a modest allocation of commodities to a typical stock-and-bond portfolio will reduce the overall risk of that portfolio without reducing the returns.

We also discussed how to implement a commodities investment strategy. We argue that the most efficient way to gain exposure to commodities is through an investment in a long-only commodity fund such as TAP. Long-only commodity funds, generally speaking, have lower fees, an important consideration in any investment decision. They have clear rules that govern how they construct their portfolios. We caution against investing in a long-only commodity fund with too many different commodities (concern about liquidity of the individual markets) or which allocates too much of the fund to one commodity or commodity sector (less diversification).

With these caveats, we believe the emergence of diversified commodity funds represents a major opportunity for investors to diversify their investment portfolios and thereby reduce portfolio volatility and risk of ruin.

Erb, C. B., and Harvey, C. R. (2005). The tactical and strategic value of commodity futures. Financial Analysts Journal 62, 2: 69-79.

Gorton, G., and Rouwenhorst, K. G. (2004). Facts and fantasies about commodity futures. Financial Analysts Journal 62, 2: 47-68.

Lamle, H., and Martell, T. F. (2005). A new era for commodity investments. Journal of Financial Transformation 15, December: 120-125.

Markowitz, H. M. (1952). Portfolio selection. Journal of Finance 7,1: 77-91.

Markowitz, H. M. (1959). Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments. New Haven, CT: Cowles Foundation Yale University.

Sharpe, W F. (1994). The Sharpe ratio. Journal of Portfolio Management 21, Fall: 49-58.