ANDREW DAVIDSON

President and Founder, Andrew Davidson & Co., Inc.

ANTHONY SANDERS, PhD

John W. Galbraith Chair and Professor of Finance, Ohio State University

LAN-LING WOLFF

Fredell & Co. Structured Finance Ltd.

ANNE CHING

Senior Consultant, Andrew Davidson & Co., Inc.

Abstract: The mortgage market has found a way to restructure mortgage cash flows to meet the needs and views of a variety of investors. The basic mortgage pass-throughs all have very similar cash-flow structures and performance characteristics. Discounts and premiums differ to some extent, but the overall investment patterns are quite similar. While the investment characteristics of these loans are similar, the needs of the investors vary significantly. The collateralized-mortgage obligation (CMO) has become the vehicle to transform mortgage cash flow into a variety of investment instruments. The driving force behind the creation of CMOs is arbitrage. CMOs will be created when the underwriter sees the ability to buy mortgage collateral, structure a CMO, and sell the CMO bonds for more than the price of the underlying collateral plus expenses. Because of the dynamic nature of arbitrage opportunities, the types of CMOs created will reflect current market conditions and can change significantly. If the end result of the cash flow structure were simply a rearrangement of cash flows, it would be difficult to create added value. CMOs are successful, nevertheless, for two main reasons. First, investors have varying needs and are willing to pay extra for a bond that meets their specific needs. Second, investors misanalyze bonds. Many investors rely on tools such as yield spread and average-life analysis. These tools are insufficient to analyze mortgage-backed securities and CMO bonds.

Keywords: collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO), principal-pay types, sequential bonds, pro rata bonds, planned amortization classes (PACs), interest-pay types, floating-rate bond, inverse-floating-rate bonds, sequential bonds, IOettes, scheduled bonds, sequential PACs, interest-only bonds, principal-only bonds, senior/subordinated structures

A collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) can be defined as a bond secured by mortgage cash flows. The mortgage cash flows are distributed to the bond based on a set of prespecified rules. The rules determine the order of principal allocation and the coupon level. The specific choice of CMOs and structured mortgage products created is determined by interaction of market demand with credit, legal, tax, and accounting requirements. The primary ingredient in CMO creation is the availability of mortgage cash flows. The cash flows provide the raw material for the CMOs. Every CMO must address the amount and availability of cash flow. In this chapter, we explain the different types of bond classes that can be created in an asset securitization.

While our focus is on the cash flow aspects of CMOs, a brief discussion of the other aspects of CMO creation is warranted. An important component of the CMO is the assurance that the investor will get the promised cash flows. The market has developed several methods for achieving this goal. Generally, the mortgages or the agency-backed mortgage pools are placed in a trust and the CMO bonds are issued out of that trust. Various legal structures can be used to create a bankruptcy-remote entity to hold the mortgages and issue the bonds. The investor looks to the trust and cash flows of the mortgages to provide the bond's principal and interest payments. These payments are assured through either a rating agency assurance (that is, a triple A rating) or through the guarantee of a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE), either Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. These mortgages back private-label CMOs issued by Wall Street firms, large mortgage originators, or mortgage conduits and are rated by rating agencies.

The tax treatment of CMOs is generally covered under the provisions of the Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit (REMIC) rules. CMOs, at times, are referred to as REMICs. In order to be a REMIC, the bonds must have a certain structure and must elect REMIC status. REMIC election drives the tax treatment of the bonds. The regular interests of the REMIC are generally taxed as ordinary bonds, whereas the residual interest bears the tax consequences of the CMO structure. Originally, the residual interest was intended to receive excess interest not distributed to regular interests. However, most residuals no longer have cash flow attached to them and are distributed primarily based on their tax consequences.

The accounting treatment for most CMOs is straightforward. However, CMO bonds sold at a premium or discount must be evaluated on a level yield basis. That is, income is determined by the yield of the bond rather than its coupon. When prepayments change, the expected cash flows of the security changes. As a result, the income stream must be adjusted accordingly. This is a complex area, especially for some CMO residuals, interest-only (IO) and principal-only (PO) securities. The rules for treatment of these bonds are subject to change. Please consult with your tax and accounting advisors before purchasing CMOs.

Once the legal, tax, and accounting issues are resolved, the investment characteristics of a CMO will be driven by the cash flows of the underlying collateral and the structure of the CMO deal. In order to understand CMOs, it is necessary to understand the rules by which the mortgage cash flows are distributed to the bonds.

The CMO can be thought of as a set of rules. The rules tell the trustee how to divide the payments that it receives on the mortgages. The rules tell the trustee in what order to pay the bondholders and how much to pay them. The rules generally can be split between principal-payment rules and interest-payment rules. Market participants have developed standard definitions for CMO types; these types specify the nature of the rules used to distribute cash flows. These standard types include principal-pay types and interest-pay types. Each bond has both a principal-pay type and interest-pay type. Table 33.1 shows the standard CMO definitions.

Each CMO represents a combination of these bond types and, hence, of the mortgage rules. In the following examples, we show how these rules are applied and how complex CMO structures can grow out of these simple rules. In this chapter, we concentrate on several of the most common principal and interest rules.

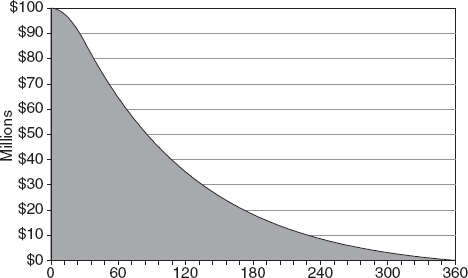

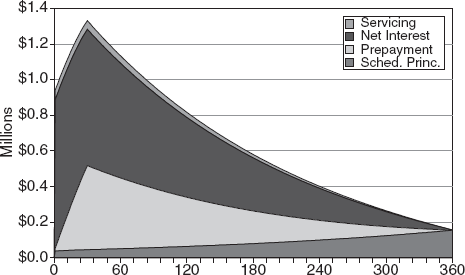

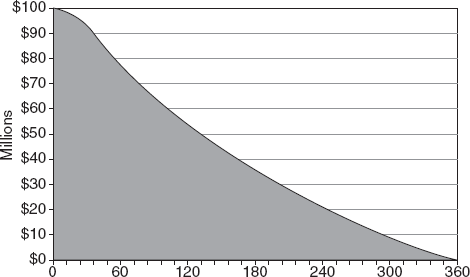

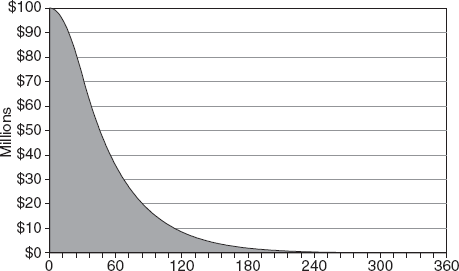

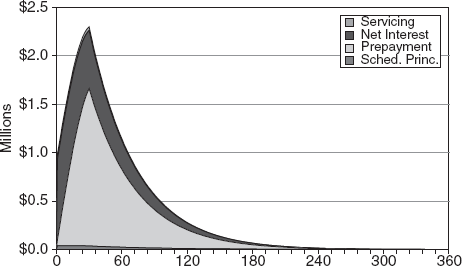

The starting point for the creation of the CMO is the mortgage collateral. For the following examples, we use newly originated agency collateral with a net coupon of 8% and a gross coupon of 8.6%. Assume a 30-year maturity and an age of 5 months. CMOs are generally priced as structured using the Public Securities Association (PSA) model. We use 175 PSA as our base speed and look at the effects on the structure of prepayments at 100 PSA and at 400 PSA. Figures 33.1a and 33.1b show the principal balance outstanding and the cash flows of the mortgages. Note that the cash flows consist of principal and interest payments. The principal payments represent both the scheduled principal payments and the unscheduled payments (prepayments). The interest cash flows consist of the net interest payment to the investor and the payment to the servicer and guarantor. The change in balances and cash flows for speeds of 100 PSA and 400 PSA are shown in Figures 33.2 and 33.3. The cash flows of mortgages are the raw material for the CMO. The cash flows of the CMO bonds must come from the mortgage cash flows. As the cash flows of the underlying pass-through change, the cash flows of the CMO bonds must also change.

Principal-pay rules determine how principal payments are split among CMO tranches. These rules can be applied alone or in combination with one another. For sequential bonds, one bond is completely paid down before principal payment begins on the next. Pro rata bonds pay down simultaneously according to a fixed allocation. Planned amortization classes (PACs) are part of a group of bonds classified as scheduled bonds. These bonds receive priority within the structure for certain principal payments. Support bonds are created in conjunction with the scheduled bond and absorb the remaining principal payments.

Table 33.1. Standard Definitions for REMIC and CMO Bonds

Agency Acronym | Category of Class | Principal-Pay Types |

|---|---|---|

AD | Accretion directed | Pays principal from specified accretions of accrual bonds. ADs may, in addition, receive principal from the collateral paydowns. |

AFC | Available funds | May receive as principal, in addition to other amounts, interest paid on the underlying assets of the series trust to the extent that the interest exceeds certain required interest distributions on this class (or related class-Freddie Mac). |

CALL | Call | Freddie Mac only; Holders have the right to direct the issuer to redeem the related callable class or classes. |

CALLABLE/CC | Callable | Receive payments based on distributions on underlying callable securities (directly or indirectly, at the direction of the holder of the related call class-Freddie Mac). |

GMC | Guaranteed maturity class | Freddie Mac only: Final payment date is earlier than the latest date by which those classes could be retired by payments on their underlying assets. Typically, holders of a guaranteed maturity class receive payments up to their final payment date from payments made on a related underlying REMIC class. On its final payment date, however, the holders of an outstanding GMC will be entitled to receive the entire outstanding principal balance of their certificates, plus interest at the applicable class coupon accrued during the related accrual period, even if the related underlying REMIC class has not retired. |

NPR | No payment residual | Receives no payments of principal. |

NSJ | Nonsticky jump | Principal pay down is changed by the occurrence of one or more triggering events. The first time the trigger condition is met, the bond changes to its new priority for receiving principal and remains in its new priority for the life of the bond. |

NTL | Notional | No principal balance and bears interest on its notional principal balance. The notional principal balance is used to determine interest distributions on an interest-only class that is not entitled to principal. |

PAC | Planned amortization class | Pays principal based on a predetermined schedule established for a group of PAC bonds. The principal redemption schedule of the PAC group is derived by amortizing the collateral based on two collateral prepayment speeds. These two speeds are endpoints for the "structuring PAC range." A PAC group is therefore defined as PAC bonds having the same structuring range. A group can be a single bond class. |

PT | Pass-through | Receives principal payments in direct relation to actual or scheduled payments on the underlying securities, but is not a strip class. |

SC | Structured collateral | Receives principal payments based on the actual distributions on underlying securities representing regular interests in a REMIC trust. |

SCH | Scheduled | Pays principal to a set redemption schedule(s), but does not fit the definition, of a PAC or TAC. |

SEG | Segment | Combined, in whole or part, with one or more classes (or portion of classes) to form a segment group or aggregate group for purposes of allocating certain principal distribution amounts. |

SEQ | Sequential pay | Starts to pay principal when classes with an earlier priority have paid to a zero balance. SEQ bonds enjoy uninterrupted payment of principal until paid to a zero balance. SEQ bonds may share principal paydown on a pro rata basis with another class. |

SJ | Sticky jump | Principal paydown is changed by the occurrence of one or more triggering events. The first time the trigger condition is met, the bond changes to its new priority for receiving principal and remains in its new priority for the life of the bond. |

SPP | Shifting-payment percentage | Freddie Mac only: Receives principal attributable to prepayments on the underlying mortgages in a different manner than principal attributable to scheduled payments or shifting proportions over time. |

STP | Strip | Receives a constant proportion, or strip, of the principal payments on the underlying securities or other assets of the series trust. |

SUP | Support (or companion) | Receives principal payments after scheduled payments have been paid to some or all PAC, TAC, or SCH bonds for each payment date. |

TAC | Target (or targeted amortization class) | Pay principal based on a predetermined schedule, derived by amortizing the collateral based on a single prepayment speed. |

XAC | Index allocation | Principal payment allocation is based on the value of an index. |

AFC | Available funds | Receives, as interest, certain interest or principal payments on the underlying assets of the related trust. These payments may be insufficient on any distribution date to cover, fully, the accrued and unpaid interest of this class at its specified interest rate for the related interest accrual period. In this case, the unpaid interest amount may be carried over to subsequent distribution dates (and any unpaid interest amount may itself accrue interest) until payments are sufficient to cover all unpaid interest amounts. It is possible that these insufficiencies will remain unpaid and, If so, they will not be covered by issuer's guaranty. |

ARB | Ascending-rate bond | Have predetermined coupon rates that take effect one or more times on dates set forth at issuance. |

DLY | Delay | A floating rate, inverse-floating rate, or weighted-average coupon class for which there is a delay of 15 or more days from the end of its accrual period to the related payment date. |

DRB | Descending-rate bond | Have predetermined class coupons that decrease one or more times on dates determined before issuance. |

EXE | Excess | Entitled to collateral principal and interest paid that exceeds the amount of principal and interest obligated to all bonds in the deal. |

FIX | Fixed | Coupons are fixed throughout the life of the bond. |

FLT | Floater (or floating rate) | Coupons reset periodically based on an index and may have a cap or floor. The coupon varies directly with changes in the index. |

IDC/DIF | Index differential | Has an interest rate that reset periodically computed in part on the basis of the difference (or other specified relationship-Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae) between two designated indexes (e.g., LIBOR and the 10-year Treasury index). |

INV | Inverse floater | Coupons reset periodically (like floaters) based on an index and may have a cap or floor. The coupon varies inversely with changes in the index. |

IO | Interest only | Receive some or all of the interest portion of the underlying collateral and little or no principal. A notional amount is the amount of principal used as a reference to calculate the amount of interest due. A nominal amount is actual principal that will be paid to the bond. It is referred to as "nominal" since it is extremely small compared to other classes. |

NPR (also above) | No payment residual | Receives no payment of interest. |

PEC | Payment exchange certificates | Freddie Mac only: Class coupons vary, in whole or in part, based on payments of interest made to or from one or more related classes. |

PO | Principal only | Receives no interest. |

PZ | Partial accrual | Accretes interest (which is added to the outstanding principal balance) and receives interest distributions in the same period. These bonds have a stated coupon, which is equal to the sum of the accretion coupon and interest distribution coupon. |

W/WAC | Weighted-average coupon | Represent a blended interest rate (effective weighted-average interest rate-Fannie Mae), which may change in any period. Bonds may be comprised of nondetachable components, some of which have different coupons. |

Z | Accrual | Accrete interest that is added to the outstanding principal balance. This accretion may continue until the bond begins paying principal or until some other event has occurred. |

CPT | Component | Comprised of nondetachable components. The principal pay type or sequence of principal pay of each component may vary. |

IMD | Increased minimum denomination | Ginnie Mae only: To be offered and sold in higher minimum denominations than those of other classes. |

LIQ | Liquidity | Intended to qualify as a liquid asset for savings institutions. LIQ bonds are any agency-issued bonds that have a stated maturity of 5 years (or less), or any non-agency-issued bonds that have a stated maturity of 3 years (or less), in each case from issue date. |

RTL | Retail | Designated to be sold to retail investors. |

R, RS, RL | Residual | Designated for tax purposes as the residual interest in a REMIC. |

RDM | Redeemable | Fannie Mae only: Certificate that is redeemable directly or indirectly as specified in the prospectus. |

SP | Special | Ginnie Mae only: Having characteristics other than those identified above. |

TBD | To be defined | Does not fit into any of the current definitions |

Interest-pay rules determine the amount of interest received by the CMO bondholders each period. Interest-payment rules are linked with principal-pay rules to produce a wide variety of bond types. One rule of CMO creation is that the combined interest on the CMO bonds must be less than the available interest from the collateral. Fixed interest payments are the most common type. The bondholder receives an interest amount, which is a constant percentage of the outstanding balance. In an accrual bond (or Z bond), the bondholder does not receive interest payments for some time period. During this time, the interest payments are converted to principal, and the balance of the investment increases. The coupon for a floating-rate bond changes based on an underlying index. Floating-rate bonds typically pay a margin above an index (frequently the London Interbank Offered Rate [LIBOR]) and have an interest rate cap. Inverse-floating-rate bonds are usually produced in conjunction with floating-rate bonds. Their coupon moves inversely with the index, usually at some multiple of the index. They typically have a cap and a floor. Principal-only and interest-only payment types provide for bonds with principal payments and no interest payment or interest payments with no principal.

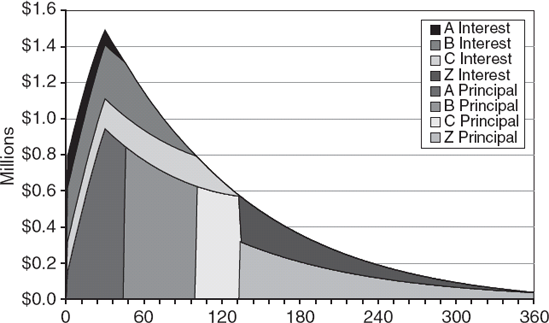

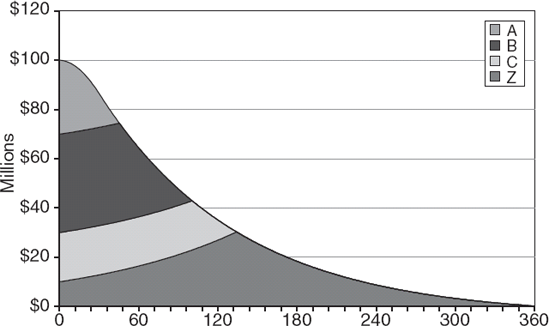

The first CMO bonds were sequential CMOs. They were created to turn mortgage-backed securities (MBS) into more corporate bond-like investments. Sequential bonds tend to narrow the time over which principal payments are received, creating a more bullet-like structure. Figure 33.4 shows the cash flow of a typical sequential CMO. In this example, classes A, B, C, and Z are sequential bonds. Class A receives all of the principal payments first. Once class A is completely paid off, then class B begins to receive principal payments. Once class B is paid off, then C begins principal payments, and so on until class Z is paid off. Note that each bond receives principal payments over a relatively narrow time period.

The interest payment on each of these tranches is fixed and equal to the net coupon of the underlying MBS. Each bond receives a monthly interest payment equal to the coupon divided by 12 times the outstanding balance of that tranche. Thus, tranches A, B, and C all receive interest payments beginning in month one. Class Z is an accrual bond. Rather than receiving its share of interest, its interest payment is converted to principal and is used to increase the balance of the Z tranche. The interest payment that should have gone to Z is used to make principal payments to tranches A, B, and C. This can also be seen in Figure 33.4. Figure 33.5 shows the balance outstanding of each tranche over time. Note that the balance of tranche A begins to decline immediately. The balance of tranches B and C are constant until the prior tranches are paid off. Tranche Z shows an increasing balance until all of the earlier tranches are paid off. The net effect is to shorten the average life of tranches A, B, and C. Typically, shorter tranches are priced at lower yields. By increasing the amount of principal received by the shorter tranches, CMO structures are able to increase the value of the CMO arbitrage.

As prepayments increase, the payments on the bonds will be received earlier. While some analysts have argued that sequential bonds offer protection from prepayment risk, it is difficult to make general statements about the amount of risk in a sequential bond. Rather than rely on a general prescription of which bonds are safe and which are risky, it is better to perform an analysis of the specific tranche that is a potential acquisition.

Much of the complexity of CMO structures arises from layering different types of principal-payment rules. Pro rata bonds provide one means to affect this layering. Pro rata bonds are two or more bonds that receive cash flows according to exactly the same rules. Cash flows available to these bonds are divided proportionally. Figure 33.6 shows an example of pro rata bonds. The figure shows only the principal payments of the bonds. Tranches Bl and B2 receive a pro rata share of the cash flows that went to class B in the earlier example. Here, Bl receives 40% of the principal while B2 receives 60% of the principal.

Pro rata bonds are created to allow for different interest-payment rules for the same principal payment and will change the risk characteristics of the bonds to make them attractive to different investors. Given this pro rata structure, there are several choices of interest-pay rules possible for Bl and B2. One possibility is that they will both be fixed-rate bonds, but with different coupons. Say Bl has a coupon of 6%. The coupon of B2 cannot exceed 9.33%, since the weighted-average coupon cannot exceed 8%. Through this mechanism it is possible to create bonds that have coupons that are higher and lower than the collateral coupon.

Another example of a pro rata bond is an IO strip. It is possible to create an IO off of any bond. For some time, REMIC rules required that all regular interests have a principal component. At that time, IOs were created with a tiny piece of principal and generally had coupons of 1,200% due to federal wire requirements. The limitation on principal has now been removed so that a pure interest strip can be created off of any bond. Some people call IOs that are created off of CMO bonds IOettes to distinguish them from lO strips created using all the interest payments of an MBS. In a CMO, lO strips are used to lower the coupon of the CMO tranche. Due to prepayment risk, investors prefer to buy bonds at a slight discount, so their yield will be less affected by changing prepayments.

Other forms of pro rata bonds are floaters and inverse floaters. Just as it is possible to create two fixed-rate bonds, where the combined coupon equals the coupon of the collateral, it is possible to create a floating-rate bond and an inverse-floating-rate bond whose coupon equals the collateral coupon.

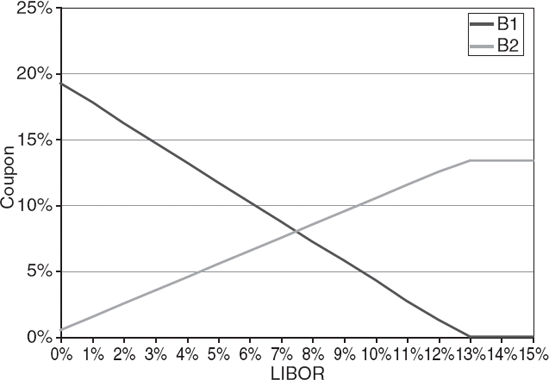

Suppose bond B2 is a floating-rate bond with a coupon equal to LIBOR + 50 basis points: If LIBOR is currently 4%, then the coupon on B2 is 4.5%. The coupon on Bl would then be 13.25%. If LIBOR rises to 5%, the coupon on B2 becomes 5.5%, while the coupon on Bl must fall to 11.75%. As LIBOR rises, the coupon on B2 floats with LIBOR, while the coupon on Bl moves inversely to LIBOR. The coupon on Bl changes by 1.5 times the amount of the change in LIBOR. This inverse floater is said to have a slope of 1.5. Because the interest must come from the fixed-interest payment of the collateral, the coupon on these floaters must be capped. The floating-rate bond cannot exceed 13.33%, while the inverse floater cannot exceed 19.25%. Figure 33.7 is a graph of the possible coupon combinations of Bl and B2. The coupon on the inverse floater is usually described by a formula. In this case, the formula would be 19.25% − 1.5 × LIBOR.

While sequential bonds may offer some allocation of prepayment risk, investors seeking more protection from prepayment risk have turned to scheduled bonds for greater certainty of cash flow. Several types of scheduled bonds exist. Here, we concentrate on planned amortization classes (PACs). PACs are designed to produce constant cash flows within a range of prepayment rates. Unlike sequential bonds, PAC bonds provide a true allocation of risk. PAC bonds clearly have more stable cash flows than comparable non-PAC bonds. The additional stability of the PAC bonds comes at a cost. In order to create a more stable PAC bond, it is necessary to create a less stable support bond. Support bonds bear the risk of cash-flow changes. Although PAC bonds are somewhat protected from prepayment risk, they are not completely risk free. If prepayments are fast enough or slow enough, the cash flows of the PAC bonds will change. Furthermore, there can be great differences in the performance of PAC bonds. As with all CMO bonds, it is better to evaluate the cashflow characteristics of the bond you are considering as an investment, than to rely on the type of the bond to indicate its riskiness. Some PAC bonds can be variable, and some support bonds can be very stable.

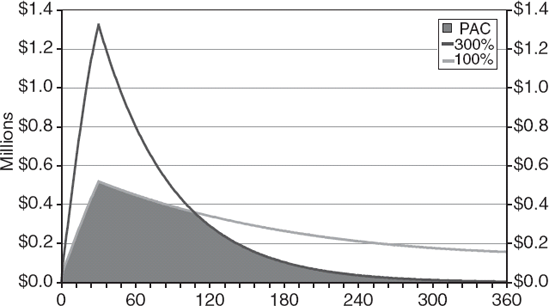

PACs are created by calculating the cash flow available from the collateral using two different prepayment speeds: a fast speed, 300 PSA, for example, and a slow speed, such as 100 PSA.

Figure 33.8 shows the principal cash flows of our collateral using 100 PSA and 300 PSA. The cash flow available each period under each scenario is the cash flow that can be used to construct the PAC bond. Under the 100 PSA assumption, there is less available in the early years of the CMO and more available in the later years. Under the 300 PSA assumption, there is more cash flow available during the early years of the CMO, and less available in the later years.

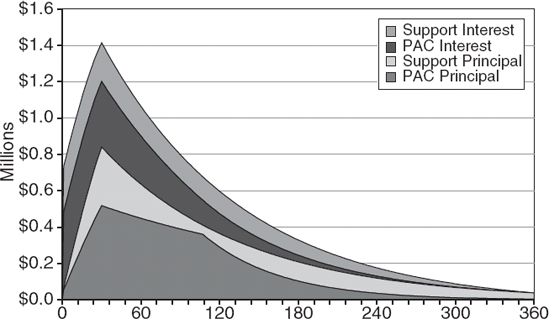

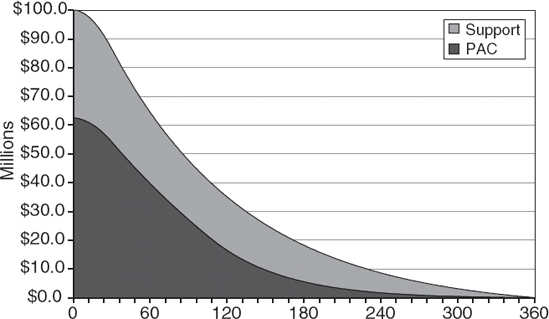

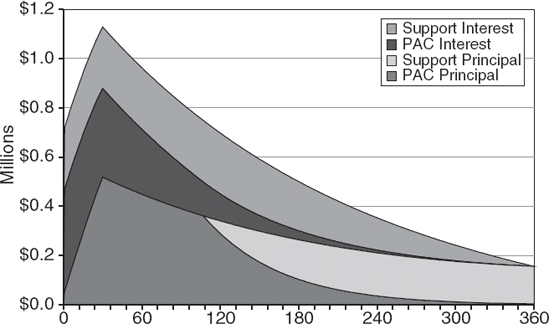

Figure 33.9 shows the cash flows of a CMO consisting of two classes, a PAC bond and a support bond, assuming a prepayment speed of 175 PSA. The PAC bond was constructed with a PAC bond of 100 PSA to 300 PSA. The principal payment pattern of the PAC bond is exactly equal to the schedule created using the two PAC band speeds. The cash flows are neither sequential nor pro rata. The support bond pays down simultaneously with the PAC bond, but the ratio of payments is determined by the PAC schedule and varies depending on prepayment rates. Figure 33.10 shows the paydown of the balance of the two classes at 175 PSA.

As prepayment rates change, the cash flow characteristics shift. At a speed of 100 PSA, far less cash flow is available in the early years of the CMO. Figure 33.11 shows the cash flows are 100 PSA. In the early years, all the principal cash flows go to the PAC bond. Principal payments on the support bond are deferred. Under this scenario, the cash flows of the support bond extend. The support bond does, however, receive more interest payments. Since 100 PSA is within the PAC bonds, the PAC bond still receives cash flow according to the original PAC schedule.

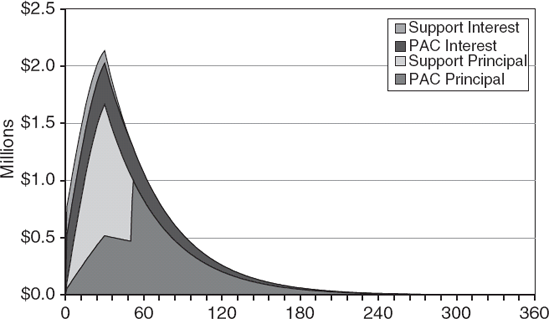

If prepayments are outside of the PAC bands, then the PAC schedule cannot be met. Figure 33.12 shows the cash flows of the CMO assuming prepayments at 400 PSA. Here the prepayment speed is outside the PAC bands. In this case, it is impossible to keep the PAC schedule. The cash flows to the support bond are accelerated. The support bond is fully paid off by month 91 and all remaining principal payments go to the PAC bond, significantly shortening its life. Even though the PAC schedule cannot be met, the PAC bond is still more stable than the support bond.

PAC bands are expressed as a range of prepayment speeds. In our example, we use 100 PSA to 300 PSA, which means that if prepayments occur at any single constant speed between 100 PSA and 300 PSA, the PAC schedule will be met. It does not mean that the PAC schedule will be met if prepayments on the collateral stay between 100 PSA and 300 PSA. Even if prepayments vary within the PAC bands, it is possible that the schedule will not be met. For example, if prepayments stay near 300 PSA for several years and then fall to near 100 PSA, the PAC bond will probably extend outside the PAC band. During the years at 300 PSA, the support bond will be nearly paid off. Then when prepayments slow, there is no way to cushion the extension of the PAC bond. Once again, analysis of the bond's cash flows are a more useful measure of the value of the bond than can be determined from its name alone.

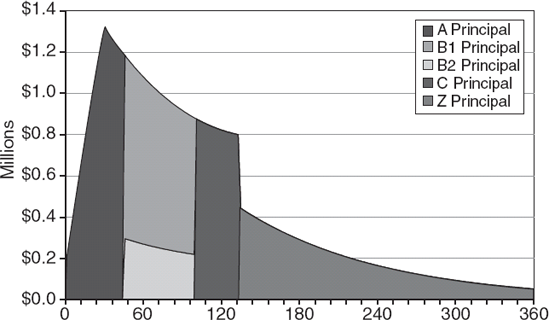

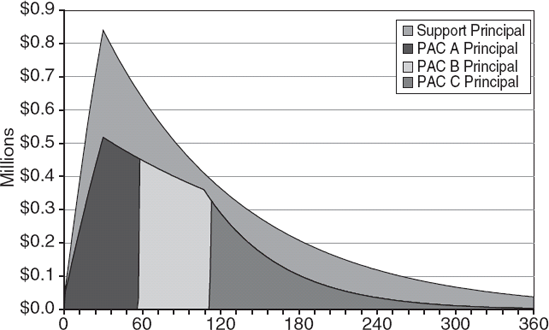

Just as sequential bonds were created to allow investors to specify a maturity range for their investments, PACs can be divided sequentially to provide more narrow pay-down structures. Figure 33.13 shows the cash flows of a CMO in which the PAC has been split into several different bonds. These sequential PACs narrow the range of years over which principal payments occur. Investors with short horizons choose the earlier PACs, whereas investors with longer horizons choose the longer PACs. While these bonds were all structured using the 100 PSA to 300 PSA PAC band, the actual range of speeds over which their schedules will be met may differ. In particular, the early bonds can withstand faster speeds than the top of the PAC band, without varying from their scheduled payments.

Sequential PACs represent another example of how the CMO structuring rules can be combined to create more complex structures in order to meet a wider variety of investor requirements. It is possible to take any bond and further structure it. For example, the sequential PACs could be split using a pro rata structure to create high- and low-coupon PACs.

Another common PAC structure strips an IO piece to lower the coupon of the CMO classes and splits the collateral into a PAC and support bond. Another PAC class is created within the existing PAC class. The more stable PACs are called PAC Is and the less stable ones are called PAC IIs. These bonds are divided sequentially into PACs with various average lives. These sequential PACs are divided pro rata in order to strip down their coupons so that the bonds trade at or below par. The remaining IO strips are sold individually or together as IOettes. The structuring continues with the support piece, which is divided sequentially. The sequential support pieces are split pro rata to create a variety of fixed-rate, floating-rate, and inverse-floating-rate bonds. Using the few simple structures we saw previously, structures with 50 or more classes can be created.

IO and PO bonds can be created within CMO structures as a type of pro rata bond as described earlier. They can also be created independently by stripping MBS. Both FNMA and FHLMC offer programs under which MBS can be split into IOs and POs. IOs and POs tend to be very volatile. By splitting principal and interest, the effects of prepayments on value are amplified.

PO bonds receive all of the principal payments. Therefore, the total amount of cash flow to be received by the PO investor is known from the start. On our $100 million of collateral, the PO investor will receive $100 million of cash flow. The uncertainty is over the timing of the cash flows. At faster prepayment speeds, the cash flow is received over a relatively short period. The cash-flow pattern can vary greatly. Figure 33.14 shows the cash flows of the PO at various prepayment speeds.

Since POs receive no interest, they are priced at a discount. Due to discounting effects, the value of the PO increases as the cash flow is received sooner. That is, other things being equal, you would rather receive your money sooner than later. The value of a PO will then be affected by the discount rate and the timing of prepayments. As interest rates fall, the discount rates fall and prepayment rates increase. Both factors serve to increase the value of the PO. POs thus become very bullish instruments, strongly benefiting from falling rates. The performance characteristics of POs, however, are very dependent on the characteristics of the underlying collateral. POs from premium collateral have very different performance characteristics than POs from discount collateral due to their very different prepayment characteristics. Furthermore, POs are very volatile instruments because slight changes in prepayment rates can have a significant impact on value.

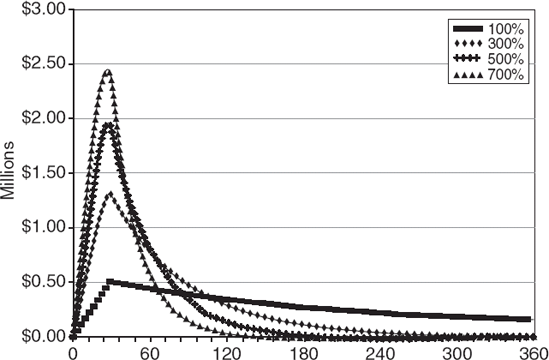

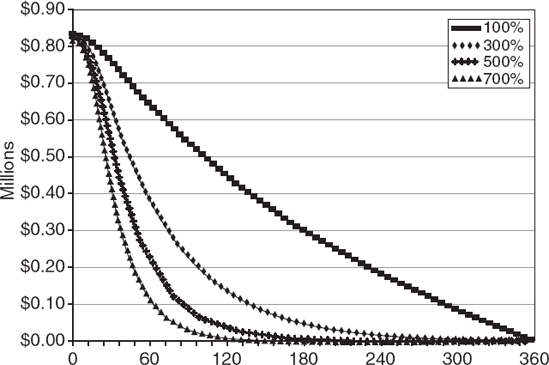

IO securities have no assured cash flows. The amount of interest received depends on the balance outstanding. As prepayments increase, the amount of cash flow received by the IO decreases. As prepayments decrease, the amount of cash flow increases. The change in cash flow can be significant. Figure 33.15 shows the cash flow of the IO under several prepayment assumptions. Cash flow under the 700%PSA assumption is just a fraction of the cash flow under the 100%PSA assumption.

IO securities have a feature that is unique in the fixed-income world. IOs tend to increase in value as rates rise and decrease in value as rates fall, because as rates rise, prepayments tend to slowdown. Slower prepayments lead to greater cash flows to the IO investor. The increase in cash flow more than compensates for the higher discount rate.

Investors should be cautious about using IOs to hedge other fixed income instruments. Although the general direction of movement of an IO is opposite to other fixed-income instruments, it is difficult to assess precise hedge ratios. IOs are extremely sensitive to prepayment expectations, and it is difficult to establish precise relationships between interest rates and prepayment rates. Highly sensitive instruments such as IOs and POs require sophisticated analysis tempered with a good deal of judgment. The difficulty in assessing these types of instruments is an indication of the limitation of current valuation tools.

So far, we have concentrated on CMO structures in which the underlying collateral or the CMO itself is guaranteed by the agencies (GNMA, FNMA, and FHLMC). For collateral that does not meet the agency standards, a different type of structure is required. With agency collateral, the investor bears no default risk. In the case of a default, the investor receives a prepayment equal to the full principal amount of the loan. If the loan is not guaranteed by the agencies, other forms of credit enhancement are required to attract investors. Credit enhancement can be either external or internal. External credit enhancement is provided by a mortgage insurance company. The insurance operates at the pool level and provides investors with the assurance that they will not suffer from mortgage delinquencies and defaults.

Internal credit enhancement operates by relying on the overall credit quality of the mortgages to produce different classes of bonds with different exposure to credit loss. Generally, a senior class is produced, which is protected from credit losses, along with a junior piece, which absorbs the losses. Senior/subordinated structures are somewhat akin to PAC bonds. However, instead of offering protection against prepayment risk, the senior class is protected from default risk.

The construction of senior/subordinated deals can become quite complex. New structures are continually being developed to make the execution more efficient. In some structures, a junior class is set up so that it is large enough to absorb worst-case losses. The guidelines for the size of the subordinated structures are set by the rating agencies (Standard & Poor's, Moody's, or Fitch). Underwriters and issuers generally seek at least a double A rating on the senior class. The junior piece generally remains outstanding until the balance of the senior piece has declined sufficiently, so that the risk of loss is minimal. Additional credit protection may come from a reserve account funded with cash or with excess interest that is not going to either the senior or junior class.

The senior/subordinated structures may be further structured using any of the tools described earlier. These CMOs tend to have fewer classes than the agency-backed CMOs.

CMOs allow mortgage cash flows to be restructured to create securities with a wide variety of investment performance characteristics. Complex CMOs are generally the result of application of relatively simple cash-flow allocation rules. While the rules may be simple, the resulting securities may be quite complex. Knowing the structure of a CMO may provide some insight into the risks of the bond. However, analysis of the actual cash flows under a variety of interest-rate and prepayment scenarios will produce more reliable results. Very often, the performance characteristics of two same-type bonds can differ dramatically.

Ambrose, B., Lacour-Little, M., and Sanders, A. B. (2004). The effect of conforming loan status on mortgage yield spreads: A loan level analysis. Real Estate Economics 32, 4: 541-569.

An, X., Deng, Y., and Sanders, A. B. (2007). Subordination levels in structured financing. (2007). In A. Boot and A. Thakor (eds.), Handbook of Financial Intermediation. North Holland, forthcoming.

Bruskin, E., Sanders, A. B., and Sykes, D. (2000). The non-agency mortgage market: Background and overview. In F. Fabozzi, C. Ramsey, and M. Marz (eds.), The Handbook of Nonagency Mortgage-Backed Securities (pp. 5-38). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Buser, S., Hendershott, P., and Sanders, A. B. (1990). On the determinants of the value of call options on default-free bonds. Journal of Business 63,1: 33-50.

Davidson, A., Herskovitz, M., and Van Drunen, L. (1988). The refinancing threshold pricing model: An economic approach to valuing MBS. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 1, 2: 117-130.

Davidson, A., Ho, T., and Lim, Y. (1994). Collateralized Mortgage Obligations: Analysis, Valuation and Portfolio Strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Davidson, A., Sanders, A. B., Wolff, L., and Ching, A. (2003). Securitization: Structuring and Investment Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, F, Sanders, A. B., Yuen, D., and Ramsey, C. (2005). Nonagency CMOs. In F. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities (pp. 579-588). New York: McGraw-Hill.

McConnell, J., and Singh, M. (1994). Rational prepayments and the valuation of collateralized mortgage obligations. Journal of Finance 49, 3: 891-921.

Mohebbi, C, Li, G., and White, T. (2006). Stripped mortgage-backed securities. In F. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Mortgage-Backed Securities (pp. 465-480). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Richard, S., and Roll, R. (1989). Prepayments on fixed-rate mortgage-backed securities. Journal of Portfolio Management 15,3: 73-82.

Rothberg, J., Nothaft, F, and S. Gabriel. (1989). On the determinants of yield spreads between mortgage pass-through and Treasury securities. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 2, 4: 301-315.