DAVID M. JONES, PhD

President, DMJ Advisors, LLC

ELLEN J. RACHLIN

Managing Director, Portfolio Management, Mariner Investment Group, Inc.

Abstract: The Federal Reserve's twin goals are to achieve sustainable economic growth and stable prices. The Federal Reserve strives also to contain inflationary expectations. The Fed seeks to influence the U.S. economy in a manner which allows it to grow at a pace which will employ all available resources but not so fast a pace as to fuel inflation. The Federal Reserve's effectiveness in achieving the dual goals of price stability and sustainable economic growth is limited to their direct influence on short-term interest rates and indirect effect on long-term interest rates. Historically, the Federal Reserve under different chairmen has favored targeting the Federal funds rate most of the time. The Federal Reserve is challenged in achieving the desired results due to its indirect influence over global capital flows. At times, global capital flows may work against what the Federal Reserve is trying to achieve. An investor who can anticipate Federal Reserve policy shifts can more accurately anticipate changes in asset valuations. The Federal Reserve, in setting short-term interest rates, ultimately affects asset repricings and valuations. An investor needs to understand the dynamics of Federal Reserve policy shifts and pay attention to key economic indicators that the Fed watches.

Keywords: price stability, monetary policy, open market operations, FOMC Meetings, discount rate changes, federal funds rate target, "leaning against the wind" policy, monetary policy transmission process, yield curve, borrowed reserves, sustainable economic growth

A significant element of competitive and successful equity and fixed income portfolio management is to understand and anticipate the effect of interest rate changes on asset prices. This chapter outlines the key components of the interest rate policy process undertaken by the Federal Reserve, the policy-making body that sets short-term interest rates. Although the Federal Reserve publicly announces its policy decisions, it is extremely useful for the portfolio manager to anticipate policy shifts. The portfolio manager who can anticipate policy shifts can more accurately anticipate changes in asset valuations. In order to anticipate policy shifts, the portfolio manager must not only understand the dynamics of the Fed's decision-making process but must watch the key economic indicators that the Fed watches.

Monetary policy is the U.S. government's most flexible policy tool. It is controlled by the Federal Reserve, which acts independently of government interference. The Federal Reserve, since early 1994, immediately announces policy decisions and communicates forthcoming policy intentions through venues such as Congressional testimony and public speeches. Other government policy instruments that influence economic activity include fiscal policy (taxes and spending), trade, foreign exchange, and other regulatory practices. But none of these government policy tools are as flexible as monetary policy.

Since the Federal Reserve's inception in 1913, it has had the primary task of ensuring that financial conditions are supportive of sustainable, noninflationary economic growth. The Fed has several tools it can employ to influence aggregate demand, output growth and price behavior. But, as will be discussed later, all of the Fed policy tools directly influence short-term interest rates and only indirectly influence long-term rates.

The effectiveness of any Fed policy on achieving the goal of price stability is limited to the influence of that policy on both short- and long-term interest rates, real and nominal. Price stability is the primary prerequisite for steady long-term economic growth. Low inflation rates enable businesses to increase their investment in infrastructure, including new machinery and high-tech equipment. Therefore, a low inflationary environment brighten the prospects for future increases in productivity and an improved standard of living.

In the short term, the Fed must juggle the simultaneous objectives of stable prices and maximum employment (sustainable growth). Although the president appoints the Fed chairman by legislative decree, the Federal Reserve is an independent agency and is accountable to the public only through the legislative branch of the U.S. government. If the Fed were not an independent agency, it could be subject to political influences promoting economic growth over price stability.

Fed-induced price stability and the absence of consumer and business inflationary expectations are essential to containing speculation and allowing the capital markets to efficiently allocate funds in support of sustainable growth. Generally speaking, capital markets efficiently allocate funds to the sectors of the economy promising the highest risk-adjusted returns. This process is absolutely crucial to the wealth-creating success of modern capitalism. But, as we will discuss later, at times excesses of capital allocation can occur. Capital markets may allocate capital to countries where the risks of debt default or likely debt downgrades appears quite high, such as Mexico in 1995 and southeast Asia in 1997, as these participants have confidence central bankers will successfully stave off defaults. This exaggerated if not misplaced faith that somebody will bail them out of bad investment or lending decisions, called the moral hazard of central banking, is one of the few downside effects to the central bankers' role of lender of last resort.

Monetary policy is more art than science. In essence, Fed policy is a process of trial and error, observation and adjustment. The Fed's policies are often countercyclical to the business cycle. At best, Fed policy makers can hope to smooth the peaks and troughs of business cycles. In pursuit of this countercyclical policy approach, when output is excessive relative to the economy's sustainable potential and is potentially inflationary, Fed officials will lean in the direction of more restraint in their policy stance. They will tend to increase interest rates, eventually slowing aggregate demand and output growth to a more sustainable and potentially less inflationary pace. Conversely, when output falters and falls below the economy's sustainable potential, recession threatens. Accordingly, Fed officials will tilt their policy stance in the direction of greater ease, and lower interest rates. Lower interest rates serve to boost aggregate demand and output growth thereby lessening the threat of recession. A word of caution: Fed officials must feel their way along after implementing policy shifts because the effects from policy shifts are long, variable, and sometimes difficult to predict. The Fed enacts policy shifts based on economic forecasts. Economic forecasting is often an uncertain exercise.

Table 4.1. Significant Economic Releases

Payroll employment | Monthly-1st Friday |

Housing starts | Monthly-3rd-4th week |

Industrial production | Monthly-3rd week |

ISM (supplier deliveries) | Monthly-1st business day |

Motor vehicle sales | Monthly-1st-3rd business day |

Durable goods orders | Monthly-4th week |

Employment cost index | Quarterly |

Nonfarm productivity growth | Quarterly |

Commodity prices | Continuously released |

One can develop an idea of the Fed's next policy objective by paying careful attention to various indicators of current economic activity. The key economic releases which serve as the Fed's intermediate policy indicators and that market participants should follow carefully include: nonfarm payrolls, ISM supplier deliveries, industrial production, housing starts, motor vehicle sales, durable good orders, labor compensation, productivity growth, and commodity prices. Table 4.1 gives the release cycles of these economic indicators. Consistent and meaningful changes in these economic indicators will signal changes in the business cycle and in Fed policy.

Nonfarm payrolls are released monthly and detail the previous month's changes in the complexion of the workforce including numbers employed, hourly pay changes and hours worked. Supplier deliveries are part of the Institute for Supply Management's monthly survey. This report reflects survey results of the purchasing managers of hundreds of industrial corporations. The survey reports on the lead time between orders placed with suppliers and delivery of those orders. The greater the lead time, the stronger the economy and the lesser the lead time, the weaker the economy.

Industrial production, released monthly, measures the collective output of factories, utilities, and mines. If final demand is high and inventory stockpiles are rapidly shrinking, future industrial production, employment, and income will be boosted as inventories are restocked, thereby stimulating economic activity. If, in contrast, final demand growth is slowing and inventory growth is excessive, future industrial production, employment, and income will weaken as inventories are trimmed, thereby depressing economic activity.

Housing starts, published monthly, are the number of new single- and multi-family housing units begun for construction in the previous month. Housing starts, which are financed, are highly sensitive to interest rate changes. If housing starts slow dramatically, this signals that interest rates are high enough in the current economic environment to choke off demand. Conversely, if housing starts are increasing, this signals that interest rates are low enough in the current economic environment to promote demand.

Motor vehicle sales, released monthly, are a key reflection of consumer confidence and income. Motor vehicle sales are strongly positively correlated to both income levels and consumer confidence.

Durable goods orders, released monthly, are new orders placed by consumers with manufacturers of "large ticket" consumer goods, expected to last three or more years. These items may include appliances or business machinery.

Commodity prices, for which the market receives continual input, are important indicators of future price rises in both producer and subsequently consumer prices. The most influential prices are those of raw goods and materials such as oil, lumber, metals, and agricultural commodities. Consistent, sympathetic, and significant price increases in these raw goods and materials will signal higher future prices in finished consumer goods.

Employment cost index which includes workers' wages, salaries and benefits is released quarterly.

Nonfarm-productivity growth which is defined as output per hour and is released quarterly, is closely followed by Fed officials. In order to estimate the economy's sustainable potential, it is necessary to add productivity growth plus labor force growth. These are supply-side factors.

It is extremely difficult to recognize meaningful and consistent changes in these economic variables: non-farm payrolls, industrial production, housing starts, motor vehicle sales, durable good orders, commodity prices employment cost index, and productivity growth. Even if changes in these variables appear consistent and meaningful, it is difficult to predict whether the changes in the economic variables are temporary or if left unchecked will be longer lasting.

If the Fed believes the changes in key economic variables are consistent and potentially longer lasting, they will take measures to influence the availability of credit in the economy which in turn influences aggregate demand and output growth. The Fed's most frequently employed policy tools include open market operations and changes to the discount rate. Less frequently, the Fed will employ changes in bank reserve requirements or verbal persuasion aimed at influencing bank behavior and capital market conditions with respect to the supply of credit to consumer and business borrowers, and even more rarely, the Fed may change margin requirements on stocks.

Through open market operations, the purchase or sale of U.S. government securities, the Fed either adds liquidity or funds into the market or subtracts liquidity or funds from the system. By changing the discount rate, the Fed changes the rate it charges depository institutions for the privilege of borrowing funds at the discount window. In January 2003, the Fed acted to tie the discount rate to the Federal funds rate. For financially sound member banks, the discount rate on primary borrowings at the discount window exceeds the Federal funds rate by 100 basis points. For secondary borrowings by less financially sound banks, the discount rate exceeds the Federal funds rate by 150 basis points. The combination of these tools can either make the cost of funds, that is, interest rates, cheaper or dearer. Open market operations work on the principles of supply and demand while changes in the discount rate directly alter the interest charged on funds. Discount rate changes are proposed by the board of directors of one or more district reserve banks for the approval by the board of governors of the Federal Reserve. Open market operations are conducted by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) in a manner consistent with decisions made at the periodic FOMC meetings. The FOMC consists of the seven members of the board of governors plus five voting bank presidents.

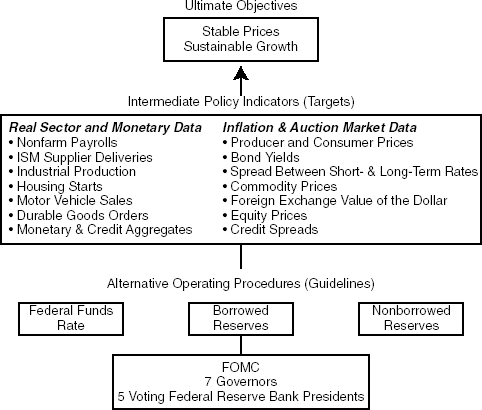

Two policy tools, changes in the reserve requirements and verbal persuasion, are tools infrequently used to reinforce stated Fed policy aims and they are used to complement policy changes already enacted through open market operations. Discount rate changes are more commonly used to put into effect Fed policy aims implemented through open market operations. These tools are employed by the Federal Reserve board of governors to underscore a policy of easing or tightening. Figure 4.1 attempts to simplify the decision making and policy implementation process of the FOMC.

Historically, the Federal Reserve, under different chairmen, has introduced two contrasting techniques for implementing open market operations (see Figure 4.1). Initially, the Fed has used as its operating procedures (guidelines) a rigid federal fund rate target, generally in effect from the late 1920s through the late 1970s. More recently, Fed officials have introduced a more flexible Federal funds rate target. When the Fed uses a rigid Federal funds rate target, Fed open market operations tend to have procyclical results. That is, during economic expansions, the Fed's use of a rigid federal funds rate target, in the face of increasing money and credit demands, would result in the full accommodation of these demands, thereby triggering an acceleration in money and credit growth, excessive real growth, and the mounting threat of inflation. Conversely, during economic downturns, the Fed's use of a rigid Federal funds rate target, in the face of declining money and credit demands, would result in weakening money and credit growth, slowing real growth, and lessening inflation pressures. Fed chairman William McChesney Martin Jr., who was Fed chairman from 1951 to 1970, started the transition to a more flexible Federal funds rate target. He sought to achieve countercyclical effects when he introduced his "leaning against the wind" policy approach. Under this approach, if economic growth appears too strong relative to the economy's sustainable potential and consequently, potentially inflationary, the Fed would tighten its policy stance and increase its Federal funds rate target in order to restrain money and credit growth with the aim of slowing aggregate demand and output growth, thereby, lessening inflationary pressures. Conversely, if economic growth weakens, the Fed would "lean" toward an easier policy stance and lower its Federal funds target in order to stimulate economic growth. Under Fed chairmen Paul Volcker (1979–1987) and Alan Greenspan (1987–2006) still greater flexibility was introduced into the Fed's federal funds rate target in order to enhance countercyclical policy actions.

Figure 4.1. Fed Policy Objectives, Intermediate Indicators and Alternative Open Market Operating Procedures

Regarding the intermediate policy indicators in Figure 4.1, Fed chairman Volcker tended to place primary policy emphasis on curtailing money and credit growth. In Volcker's own words in a statement before the Joint Economic Committee of the U.S. Congress on June 15, 1982, "[a] basic premise of monetary policy is that inflation cannot persist without excessive monetary growth, and it is our view that appropriately restrained growth of money and credit over the longer run is critical to achieving the ultimate objectives of reasonably stable prices and sustainable economic growth." Subsequently, however, Chairman Greenspan found it necessary to lessen the Fed's emphasis on monetary and credit growth in favor of greater policy emphasis on a wider range of intermediate indicators of the real sector, inflation, and auction (financial) markets. Greenspan feared that owing to globalization, securitiza-tion, and, most importantly, financial product innovation such as hedge funds, money and credit growth was no longer a reliable predictor of economic activity and inflation. Greenspan also placed more emphasis on transparency and verbal persuasion in seeking to increase the effectiveness of monetary policy.

The monetary policy transmission process has always been a long and variable one. In the past the banking system, the conduit for monetary policy, was the dominant source of credit for consumers and businesses. Typically, it has taken from six to twelve months for a shift in monetary policy to work its way through the banking system and capital markets to impact aggregate demand and output. It takes even longer for a given policy shift to influence price behavior. Complicating this process in today's world, a declining share of credit is supplied through the banking system and a rising share of credit is supplied through globally integrated capital markets. As a result, the Federal Reserve today more than in the past, must be highly attuned to financial market participants' perceptions of Fed intentions and potential market impact of the Fed's perceived intentions. The banking system remains the point of contact for the Fed when it initiates shifts in policy stance. However, Fed intentions and related market expectations of their intentions remain a critical concern in the transmission of Fed policy shifts. This process results in capital market asset price and interest rate adjustments that ultimately influence changes in aggregate demand, output growth, and inflation.

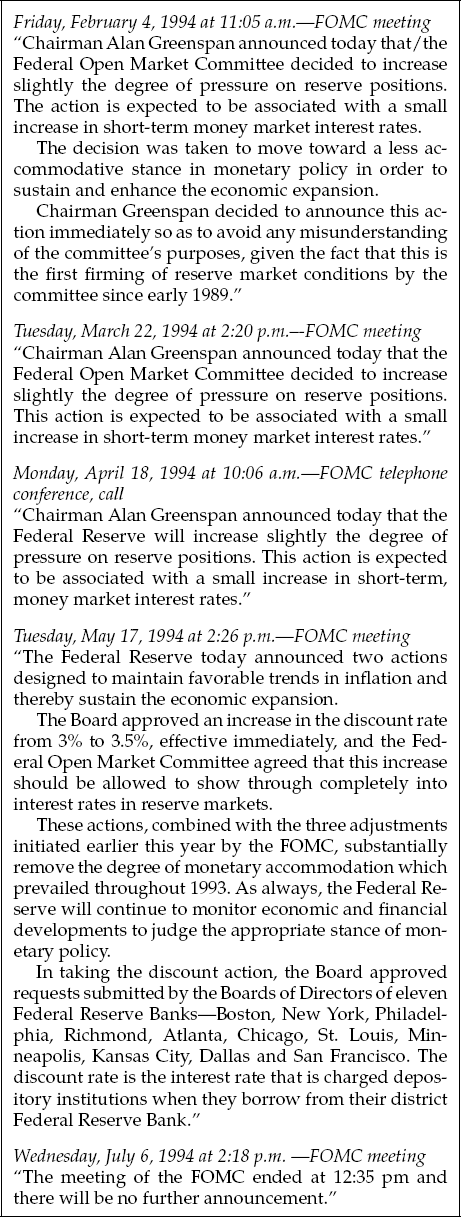

Fed authorities began in February 1994 to immediately announce policy decisions. (See Figure 4.2 for policy statements following FOMC meetings.) Today's Fed monetary policy transmission process is a transparent one. Monetary policy transparency easily conveys Fed policy intentions. Typically, Fed officials, through speeches, interviews, and congressional testimony, will seek to prepare financial market participants for any policy shift that may be in store in upcoming policy meetings. Clear information on current Fed policy helps the monetary policy transmission process operate more effectively. Under former Fed chairman Greenspan, the Fed sought to be more transparent, and refined its methods of communication.

Historically, the Fed policy transmission process has worked largely by manipulating the cost of credit as supplied by the banking system. Specifically, to effect a policy shift, the Fed has traditionally begun by changing the composition of bank reserves. For example, more Fed restraint means the Fed manipulates a rising share of borrowed to total reserves, resulting in an increase in the cost of reserves. The increased cost of reserves is reflected in a higher Federal funds rate. (The Federal funds rate is the rate on bank reserve balances held at the Fed that are loaned and borrowed among banks, usually overnight.) Conversely, less Fed restraint (more ease) means the Fed manipulates a declining share of borrowed reserves to total reserves. This action results in a declining cost of reserves that is reflected in a lower Federal funds rate. Borrowed reserves are those reserves that banks borrow temporarily at the Fed's discount window for purposes of adjusting their reserve positions. Banks traditionally try to avoid borrowing at the Fed discount window. There is a perception that such borrowings are a sign of financial weakness. Banks that are forced to borrow temporarily at the discount window will, generally, first turn to other sources of loanable funds such as Federal funds or repo borrowings. Figure 4.1 describes the importance of bank reserves to Fed policy implementation.

Figure 4.2. Sampling of the Federal Reserve's Official Statements of FOMC Actions, First Half of 1994

Banks, when faced with greater Fed restraint and a rising cost of loanable funds, find their net interest margins narrowing or their profits declining. In that case, the yield curve typically flattens or, when the Fed is tightening aggressively, inverts as short-term rates are pushed above longer term rates. Under these circumstances, banks have less incentive to increase their investments and loans. This results in a decline in the availability of funds and an increase in the cost of bank credit to consumers and businesses. Therefore, consumers and businesses will cut back on their borrowing and spending. This in turn results in a declining rate of increase in real economic growth and eventually, a moderation in inflation pressures. Conversely, a Fed move toward an easier policy posture reduces banks' cost of funds. Banks find their net interest margins widening or profits increasing because the fed funds rate is far more elastic than long-term interest rates and the yield curve will steepen. Banks' incentive to increase the availability and reduce the cost of credit increases. This stimulates consumer and business borrowing and spending, thereby spurring real economic growth and eventually triggering a rise in inflationary pressures. The only exception to our converse case is in the environment of an inverted yield curve such as the U.S. government bond curve in the early 1980s. Despite the Fed's efforts to ease short-term rates in the initial stages, the reduction in the cost of funds to banks may not have a significant impact on potential profit margins if the yield curve is inverted enough. Long-term rates may be too low on a relative basis to short-term rates to make bank or other financial institutions' extensions of long-term credit profitable, at least initially.

To view this monetary transmission process from the investment side, Fed policy shifts set off a chain reaction. For example, in the case of a Fed shift towards a more restrictive policy posture, investors who hold short-term credit market instruments such as Treasury bills or money market mutual funds will find interest rates on their short-term investments moving up to higher and more attractive levels relative to yields on longer-term bonds. Accordingly, investors will shift their investments down the yield curve. They will sell longer-term bonds and place the proceeds in shorter-term money market investments. This process will result in rising longer-term interest rates. Rising longer-term interest rates will, in turn, make the returns on bonds more attractive relative to the returns on stocks. As a result, investors will sell stocks, place the proceeds in bonds, and stock prices will decline. As capital market expectations of future Fed restrictive intentions are formed, these portfolio asset adjustments between money market investments, bonds, and stocks will be hastened and intensified.

Since the mid-1970s, there has been a sharp decline in the proportion of bank credit to total credit available. The bank share of total credit continues to fall. In mid-1970, it was 55%. By 2006, the banks' share of total credit was reduced to 25%. The main factors contributing to the declining bank share of total credit have been globalization of credit resources, securitization, and financial product innovation. The result has been a rising share of credit extended directly through the capital markets to consumers and businesses. Among the major new nonbank institutional suppliers of credit through the capital markets are mutual funds, hedge funds, pension funds, finance companies, and insurance companies. Currently, with the advent of the information revolution, these nonbank lenders are virtually in as good a position as bank lenders to assess market and credit risks.

Today, the Fed's policy transmission process works increasingly to a greater extent through capital market asset price adjustments and interest rates (that is, bonds, stocks, etc.) than through the availability of funds. As in the past, the Fed initiates a policy shift by changing the composition of bank reserves. As we have previously explained, there is a resulting change in the cost of funds as reflected in a change in the Federal funds rate. The Federal funds rate prompts positively correlated changes in short-term market rates. These changing costs of short-term credit include bank loans made at the prime rate and funds raised in the commercial paper market. The impact on capital market price adjustments work in the following manner: as short-term borrowing costs rise, borrowers find longer-term borrowing rates relatively more attractive. Eventually, corporate bond and fixed-rate mortgage offerings increase, driving up longer-term interest rates. This impact of Fed policy shifts on short-term and long-term market interest rates is magnified as Fed intentions are recognized by capital market participants. The participants form expectations of further Fed tightening (easing) moves, thereby affecting longer-term interest rates. Longer-term interest rates are influenced by the average of expected short-term rates plus a term premium that includes inflation expectations. The effect of capital market participants is reflected in the changing shapes of the yield curve as the Fed funds rate changes.

Rising longer-term interest rates and declining stock prices will increase the cost of capital. Increasing the cost of capital decreases business investment. Also, higher longer-term rates depress housing activity. In addition, declining financial asset prices depress consumer wealth and consumer spending, resulting in a decline in the pace of real economic activity. This process serves to moderate inflationary pressures. Commodity prices are likely to be falling in such an environment. Moreover, increasing interest rates will generally cause the value of the U.S. dollar to appreciate in the foreign exchange markets relative to other currencies. A stronger U.S. dollar will cause a decline in exports and a rise in imports, all other factors being equal. This rising trade deficit also serves to dampen economic activity.

Important influences on the global financial environment include: market deregulation or regulation, financial innovation, integrated global financial markets, and advanced information processing and communications technology. There is a massive pool of mobile capital that relentlessly seeks out countries where business activity generates the highest possible return for a given amount of risk. In order to compete effectively for capital from global investors, countries must pursue disciplined macroeconomic policies and pro-business microeconomic policies including deregulation and privatization. Countries competing for capital must aim for balanced and sustained noninflation-ary growth.

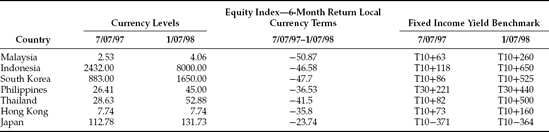

A more sobering lesson for modern-day central bankers is their reduced effectiveness in controlling massive global capital flows and related financial asset price bubbles. At times this has been manifested in capital market participants' overly optimistic view of central bankers' abilities and desire to stave off debt defaults. This may be particularly true in the case of staving off sovereign and quasi-sovereign debt where there is a history of central bankers providing meaningful amounts of liquidity. The legacy was underscored in the Mexican financial crisis in 1995. The U.S. government provided amounts up to US$50 billion to the Mexican government, staving off a debt default. The benefits of staving off the Mexican default were not without drawbacks. This lesson can be found in the Asian financial crisis that began in mid-1997. The Asian financial turmoil began in the rapidly growing economy of Thailand and spread to the other Southeastern Asian countries of Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. These developing countries had benefited from an abundance of foreign liquidity. But the heavy capital inflows eventually resulted in excessive growth, mounting trade deficits, and speculative financial bubbles typically manifested in frenzied local bank-financed speculation in equities and real estate. The currency crisis in these Southeast Asian countries was triggered as escalating trade deficits scared away global money managers, triggering a rapid depreciation in their currencies, with interest rates rising sharply in response. As the bubble burst, real estate and equity prices plummeted. This unforeseen instability posed a major threat to the affected countries' banking systems, as bad debts mounted.

It was not until equity market selling pressures spread to Hong Kong that the rest of the world began to take serious notice. With the return of Hong Kong to Mainland China, the Chinese government kept the Hong Kong dollar pegged to the U.S. dollar as a matter of political principle. Nevertheless, speculators continued to attack the Hong Kong dollar on the assumption that it had to fall in line with other southeastern Asian currencies in order for Hong Kong to remain competitive. In its effort to fight off the speculative attack on the Hong Kong dollar, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority was forced to sharply increase interest rates, thereby weakening the Hong Kong real estate market and threatening Hong Kong banks with mounting bad debts.

Next, the Asian currency crisis spread to the larger South Korean economy, where the heavily indebted financial system was vulnerable, and ultimately to the huge Japanese economy which was still attempting to recover from the bursting of its own 1980s financial bubble. Then, like a rapidly spreading contagion, the Asian currency depreciation and equity market plunge spread to Latin America and even eastern Europe and Russia where previously high-performing debt and equity markets registered extremely disorderly declines, and ultimately to declines in the western European and U.S. stock markets. Table 4.2 illustrates the magnitude of these Asian market declines.

The importance of the Asian financial crisis is that it illustrates the lessening influence that central bankers have on today's globally integrated capital market flows, apart from serving as last-resort lenders of liquidity. The role of last-resort lender, however, should not be minimized. The central bank and supra-led package of loans to Mexico in 1995 staved off a dramatic currency crisis that could have led to a debt default. With the stunning advances in information processing and communications technology, global money managers can move capital around the world at virtually the speed of light. This capital, as already noted, seeks out opportunities offering the highest risk-adjusted returns, but it flees from turmoil. The point is that the increasingly efficient global capital markets are linked more tightly than ever before. Apart from maintaining anti-inflation credibility and serving as lenders of last resort, central bankers, including the U.S. Fed chairman, may in the future have only a marginal influence on these massive global capital market flows and related financial asset price bubbles.

Moreover, and perhaps, since the Asian currency turmoil, it is the stark power of the global capital markets themselves rather than domestic politicians or central bankers that are forcing major financial system changes in the affected countries, including the desirable privatization of public corporations and large scale banking reform. The only means by which governments (or the IMF) can stabilize market forces is to respond by offering larger or more effective financial reform packages than global capital market participants expect. For example, global money managers are demanding that bank reform include provisions for allowing insolvent banks to fail and for the weaker banks to be acquired by healthy domestic or foreign financial institutions. In addition, taxpayer funds, along with deposit insurance, must be used to pay off depositors in failed banks. Also, most importantly, bank reform must make provision for transparency, including full disclosure of bad loans and off-balance-sheet items by banks and securities firms.

Huge, global pools of mobile capital may serve to actually discipline national and global macroeconomics policies. If, for example, any developed or emerging country tries to boost growth through overly stimulative macro-economic policies that are potentially inflationary for political reasons, its trade deficit will worsen and its currency will depreciate. Global institutional investors and money managers will become fearful of the increased inflationary threat and sell bonds, thus pushing long-term interest rates higher and helping to choke off growth in that developing or emerging country.

Former Fed chairman Greenspan was faced by a "conundrum" when he and his fellow policy makers began a prolonged series of rate firming actions mid-2004. Specifically, despite an impressive series of short-term rate-hikes, long-term rates actually declined, reducing the effects of Fed's firming actions. Eventually, Fed officials concluded that this atypical situation in which Fed policy was becoming less accommodative as the capital markets were becoming more accommodative, reflected a unique combination of low inflation expectations, a global savings glut, heavy global carry trades by hedge funds and other large institutional investors, and currency interventions, especially by Japan and China.

Accordingly, the best that any country can do for its citizens is to create a favorable economic climate for participation in the world economy. There are many important economic building blocks for positive participation in the world economy. These building blocks include deregulation, privatization, free markets, minimal government interference, longer-term productivity-enhancing measures (investment in education, job training, research as well as the implementation of technological innovations, and rewards for savings and investment), and, above all, central bank anti-inflation credibility and consistency. Longer-term price stability creates steady, predictable levels of economic growth. These are the rewards of pursuing a monetary policy that seeks price stability and, thereby, sets the stage for enhanced productivity.

In sum, while central bankers still play a key stabilization role in the effort to ensure that financial conditions are supportive of sustainable economic growth, the ability of central banks to influence massive global flows of mobile capital and related asset price bubbles is diminishing. This raises the spectre of additional currency crises from time to time, not unlike those in Mexico in 1995 and in Southeast Asia in 1997. To be sure, central bankers can help limit the private sector's speculative tendencies by maintaining a high level of anti-inflation credibility. Moreover, central banks can help contain the damage when asset price bubbles break by serving as last-resort lenders of liquidity. But in the final analysis, these central bank influences are marginal compared with today's sheer power of global capital market forces.

In general, central bankers have the mandate to create an investment environment which results in attractive risk-adjusted return on capital and stable capital flows. The Federal Reserve's policy transmission process influences the expectations of capital markets participants. While the Federal Reserve alters short-term borrowing rates, all lenders of capital adjust their cost of capital in response.

The Federal Reserve's policy shifts are countercyclical and affect the forward economic environment. Evident several months after the fact, the impact of these policy shifts is designed to enhance the economic environment. A positive economic environment attracts stable capital flows which ultimately aid stable, noninflationary economic growth. This is the ultimate goal of a central banker.

Chang, K. H. (2003). Appointing Central Bankers: The Politics of Monetary Policy in the United States and the European Monetary Union (Political Economy of Institutions and Decisions). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chappell, H. W. Jr., McGregor, R. R., and Vermilyea, T. A. (2005). Committee Decisions on Monetary Policy: Evidence from Historical Records of the Federal Open Market Committee. Boston: MIT Press.

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. (2001). A Prescription for Monetary Policy: Proceedings from a Seminar Series. Toronto: Books for Business.

Friedman, M., and Schwartz, A. J. (1971). Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gruben, W. (1997). Exchange Rates, Capital Flows, and Monetary Policy in a Changing World Economy (The Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas). Germany: Springer.

Greenspan, A. (2004). Monetary Policy and Uncertainty: Adapting to a Changing Economy. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. University Press of the Pacific.

Jones, D. M. (1989). Fed Watching and Interest Rate Projections: A Practical Guide. New York: New York Institute of Finance.

Jones, D. M. (1992). The only game in town (monetary policy of the Federal Reserve System under Chairman Alan Greenspan). Mortgage Banking 53, 1: 35– 38.

Jones, D. M. (1996). The Buck Stops Here: How the Federal Reserve Can Make or Break Your Financial Future. New York: Prentice Hall Trade.

Jones, D. M. (2002). Unlocking the Secrets of the Fed: How Monetary Policy Affects the Economy and Your Wealth-Creation Potential. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kettl, D. (1986). Leadership at the Fed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1978). Manics, Panics and Crashes. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Meltzer, A. H. (2004). History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1: 1913–1951. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meyer, L. H. (2004). A Term at the Fed: An Insider's View. New York: Harper Collins.

Wooley, J. T. (1986). Monetary Politics: The Federal Reserve and the Politics of Monetary Policy. London: Cambridge University Press.