BRIAN K. HAENDIGES, FSA, CRC, CRA

Head, Institutional Defined Contribution Plans, ING Retirement Services

Abstract: One of the most prevalent investment options used by defined contribution plans in the United States is a stable value option, one that provides protection of invested principal and accrued interest to individual plan participants. The funding vehicles that back stable value options are diverse, yet retain many common elements, including the accumulation of interest, some level of assurance of stability of principal, and the participant right to withdraw funds for plan benefits at book value. Both the purchasing of these products by defined contribution plan sponsors, and the issuance of them by providers, require careful consideration of those product features that are different from one product to another. This is especially important given an aging Baby Boomer population that is spurring a renewed interest in product capabilities that allow them to protect and manage the income on assets that they've accumulated for retirement. Stable value products and features are also attracting interest for applications outside of defined contribution plans, and the lessons learned from using these products in a defined contribution environment lend themselves to extrapolation in other venues.

Keywords: stable value option, stable value products, guaranteed interest rate, stability of principal, book value withdrawals, book value benefits, credited interest rate, market value adjustment, defined contribution plans, guaranteed investment contract or guaranteed income contract (GIC), portfolio rate, separate account GIC, synthetic GIC, GIC pools, stable value pooled fund, defined contribution funding, Health Reserve Account (HRA) funding, protection of principal, guaranteed fund, safe fund, defined benefit liability defeasance, credited rate formula, general account, separate account, trust account, rate reset frequency, deferred sales charge, fixed account, commercial mortgages, private placement, mortgage pass-through securities, guaranteed account

This chapter will provide a description of the market drivers of stable value products, an overview of the different types of stable value products available and how they are structured and used, buyers of stable value products, common features of stable value products, some of the issues faced by both users and issuers of stable value products, and some of the positives and negatives of different stable value products. It also explores some of the lessons learned from the history of stable value products and how the products and their features might be applied as principal-protected products experience market growth driven by demographic and psychographic changes in the retirement markets.

Virtually every participant-directed or defined contribution retirement plan, regardless of plan size or market, maintains a participant investment option that returns to its investors a stable return over time. In other words, much like a savings account at a bank, funds deposited into this stable value option are credited with interest, and invested principal is protected. Often called the guaranteed account, or the fixed account, this option is available in 401(k) and 401(a) plans offered by privately held corporations, 403(b) plans offered to teachers and not-for-profit workers, and 457 deferred compensation plans offered to governmental employees, and it often holds 15% to 35% of participant investments. Why are these options so popular, especially in a world where mutual fund companies and financial advisers have promoted diversification and emphasize equity investing?

Behavioral finance research has shown a strong preference by investors to avoid losses, even if it means forgoing an even larger opportunity for gains. For participants concerned about safety, stable value options provide some measure of protection at all stages of the asset accumulation cycle. Stable value investments are popular with conservative investors or investors just starting out who may be nervous about loss of their investment. Mid-career investors use stable value options to complement and provide more flexibility with their equity investments. Near retirees and retirees use these options to protect accumulated assets and guarantee an income stream.

Most employers that offer defined contribution plans make available a number of investment options to participants, often across a range of investment classes and offering varying degrees of risk. Though the standard varies by type of plan, all plan sponsors have some fiduciary obligation to provide a diversified menu to their participants. Stable value helps fill one of the options at the conservative end of the spectrum for many employers.

Over a full interest rate cycle, longer-term fixed income investments will generally provide higher returns than shorter-term investments. However, in order to earn those higher returns, the investment provider needs to be able to lock up the funds on a basis consistent with the maturity schedule of the investments. Stable value options are designed to create just such a return paradigm. By investing longer, but limiting asset liquidity to participant benefit events, stable value options can capture the returns of longer-term investing and still provide participants liquidity when they need it. As a result, stable value options generally will generate a yield for participants of 2% to 3% more than money market funds over a full investment cycle. That incremental return can mean a substantial benefit to the participant in retirement as compared with other principal-protected investments.

When defined contribution plans were first made available to employees, many providers started by offering participants only a single investment option—a fixed or stable value option. This may perhaps be driven by the long legacy that life insurers have had with fixed income products backing other types of liabilities such as life insurance and defined benefit plans. Within defined contribution plans, providers gradually made other options available, at first proprietary variable investment funds, and later nonproprietary funds. However, many investors who started in stable value still maintain a substantial allocation. Interestingly, this focus on stable value as a starting point may have implications for providers in countries where individually directed defined contribution plans are just now emerging. In order to attract investors at the outset, some protection of principal, and a perception of "simple and safe" may be required.

There is a wide variety of funding vehicles from which employers may choose when funding a stable value option. One consideration is whether to purchase a single product or multiple products. Many plans, even large ones, will manage their stable value option so that it is invested in a single product. Others will buy multiple products and pool the returns on each to create a "blended rate" to be credited to participants. Either way, there is an extensive array of choices. Table 63.1 shows the distribution of assets backing stable value investment options by product type, with total assets approaching half a trillion dollars.

Table 63.1. Distribution of Stable Value Assets by Product

Stable Value Product Type | Assets as of December 31, 2006 |

|---|---|

Source: 2007 LIMRA International, Inc. and Stable Value Investment Association, and industry estimates. | |

General account portfolio rate | $100-$200 billion |

General account GICs | $31 billion |

Separate account GICs | $16 billion |

Synthetic GICs | $198 billion |

Other | $65 billion |

Total | $400-$500 billion |

Table 63.2. Typical Insurer General Account Assets

Asset Type | % of Portfolio |

|---|---|

Source:Lehman Brothers analysis of top 54 companies, statutory assets as of December 31, 2004. | |

Mortgage loans and real estate | 12% |

Mortgage-backed securities | 11% |

Investment-grade bonds, public and private | 42% |

Asset-backed securities | 11% |

Foreign- and emerging-market debt | 8% |

High-yield bonds, public and private | 4% |

Other | 12% |

The earliest form of stable value investment provided in defined contribution (DC) plans was the insurance company general account. It's called the general account because the assets backing promises to DC investors are commingled with assets backing other promises by the insurer to its customers. These assets are typically almost all fixed income, and include less liquid higher-yielding securities like commercial mortgages and private placement bonds as well as publicly traded fixed income securities. For purposes of determining credited interest rates, the assets may be segmented into different portfolios, but from an ownership perspective, they are essentially in one big pool. Table 63.2 shows a typical distribution of assets in an insurance company general account.

Credited rates in a portfolio rate product are typically set periodically, again like a bank savings account, without being tied to a specific formula. Rather, the insurer's incentive to maintain rates is simple competitive pressure, comparing the rate to other offerings available to participants in other products or from competitors. The account will often have minimum interest rate guarantees associated with it, which can be lifetime guarantees, annual guarantees, or guarantees for a shorter time period. A handful of products tie their guarantees to an index or use a formula, but they are infrequent.

General account products are more frequently seen in IRS Section 403(b) and 457 defined contribution plans, where it makes it easier for the provider to meet state insurance law and securities law requirements. They are also an effective investment for smaller plans, allowing investing in a substantial diversified pool.

A guaranteed investment contract or guaranteed income contract (GIC) works notionally much like a certificate of deposit at a bank, only with the employer rather than an individual as a buyer. In essence, the issuer accepts a block of funds from the contract holder, usually a defined contribution plan sponsor, and then guarantees a rate of return on those funds over some time period. This rate of return will reflect the yields currently available on the type and quality of assets purchased with the funds. GICs reached their heyday in the early 1980s when long-term interest rates peaked at over 14%, but are still used by plans today. As rates occasionally edge up, their popularity also climbs. A variation of GICs has also been used as a funding vehicle for foreign entities.

The most basic structure of a traditional GIC is a fixed-rate, fixed-term contract where an insurer accepts deposits to its general account over a specified time period or in specified amounts. These deposits are then left with the insurer for the remaining term of the contract, and are credited with a declared rate of interest. For example, an insurer might agree to accept deposits to a GIC over the next year, and credit the GIC with an interest rate of 8% provided the funds are left with the insurer for the following four years. The 8% interest rate would be guaranteed for the entire five-year term of the contract.

An alternative approach would be to guarantee a minimum rate of interest on all deposits (e.g., 3%) and then allocate each deposit to a calendar-year cell corresponding to the year in which the deposit was made. Each cell would be credited with its own rate of interest and have its own rate guarantees reflecting the investment conditions at the time the deposits were made. This is often referred to as the "investment year method." The credited rate reported to the contract holder under this approach is usually a composite or blend of the rates in each cell. The investment year method has declined in use due to administrative complexity and insurer underwriting issues, but persists in legacy form.

At the end of the contract term, the insurer may be obligated to return the contract holder's principal and interest in a lump sum, or in a series of installments over time. The contract holder may also elect to roll maturing principal and interest into another GIC that is able to accept new deposits. In this case, the contract holder could then have several GICs in force with the same insurer at one time.

Bank investment contracts (BICs) are agreements between a bank and the plan sponsor or trustee that have deposit and maturity characteristics similar to those of GICs. A plan sponsor might choose a BIC over a GIC in order to lower their credit exposure to the insurance industry. BICs have declined in use due to issues relating to FDIC deposit insurance coverage, and the availability of more popular alternative products. Again, they may still be seen occasionally in an older portfolio.

Insurers developed separate account products in order to offer the contract holder the same investment expertise as through a traditional GIC, but with a decreased credit exposure to the insurer's general account. In the case of insolvency, the holder of a general account GIC would be treated as any other policyholder in determining the disposition of the insurer's assets. With separate account products, the assets underlying the contract are held in a separate account and are generally not chargeable with the insurer's other liabilities, thereby reducing the credit risk faced by the plan sponsor.

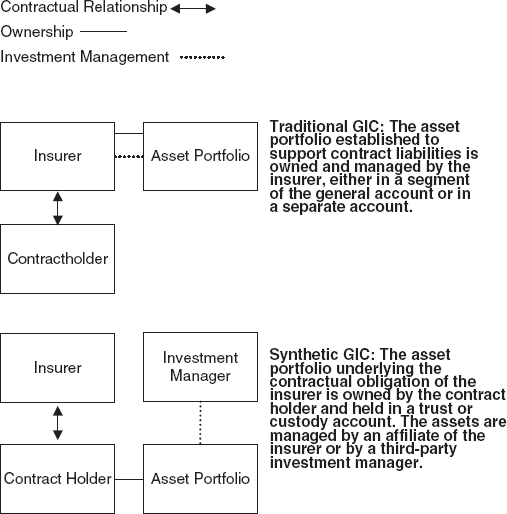

Synthetic GICs have become the most popular stable value funding option for large plans, as plan sponsors have sought additional diversification of credit risk. Under a synthetic GIC, the fixed income assets are owned by the plan sponsor and held in trust for plan participants. The plan sponsor or trustee selects an investment manager or managers for the fixed income portfolio, and the synthetic GIC issuer then "wraps" the portfolio in a contract that guarantees a rate of interest based on the performance of the investment portfolio and provides benefit responsiveness for plan participants. The fixed income portfolio manager may be either a third party or an affiliate of the synthetic GIC issuer. Figure 63.1 shows the operation of a typical synthetic GIC.

Insurance insolvency laws vary by state, but most states have adopted a law similar to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners' (NAIC) Insurers Rehabilitation and Liquidation Model Act. Table 63.3 shows the priority of insurance company claimants under the Model Act in the event of insolvency. Holders of traditional GICs, separate account products, and synthetics would generally be treated as Class 3 claimants (that is, on a par with other policyholders of the insurer). However, holders of separate account products have an advantage over general account contract holders in that, if the assets in the separate account are "insulated" from the general account, the assets in the separate account cannot be used to satisfy any claims of the insurer other than those of investors in the separate account. In this case, the credit exposure to the general account is equal to only that portion of the insurer's obligation, if any, in excess of the value of the separate account assets. Holders of synthetic GICs face a similar credit position, but have an added layer of protection on the underlying assets since they are legally owned by the contract holder rather than the issuer.

Table 63.3. Priority of Insurance Company Claimants in Insolvency

Priority Class | Claimants Included |

|---|---|

Source:NAICInsurers Rehabilitation and LiquidationModel Act, Copyright©NAIC 1995. | |

Class 1 | Administrative expenses approved by the receiver, including filing fees, the costs of recovering assets of the insurer, and compensation for services rendered in the rehabilitation or liquidation. |

Class 2 | Administrative expenses of guaranty associations, not including payments and expenses incurred as direct policy benefits. |

Class 3 | Policyholder claims for insured losses and unearned premiums, including those of federal, state, and local governments, as well as covered claims incurred by guaranty associations. |

Class 4 | Claims of the federal government other than those included in Class 3. |

Class 5 | Debts due to employees (other than principal officers and directors) for services and benefits. |

Class 6 | Claims of general creditors and persons not elsewhere classified. |

Class 7 | Claims of any state or local government for a penalty or forfeiture. |

Class 8 | Surplus or contribution notes, or similar obligations. |

Class 9 | Claims of shareholders or other owners arising from ownership. |

One particular subset of the synthetic GIC structure worth mentioning is the global wrap. Under this type of arrangement, a single plan sponsor will purchase several synthetic GICs, that is, several different fixed income asset managers and several different wraps from wrap providers. The plan will then create cross-coverage connections so that the wrap providers support each other in the event that one fails or shows signs of credit weakness. Also, either a wrapper or manager may be replaced for under-performance or credit concerns. This structure would be mostly used with very large plans with several billion dollars of retirement funds.

Pooled funds, still sometimes referred to informally as GIC pools even though GIC usage to fund them has declined, require less decision making on the part of the plan sponsor. Rather than the plan selecting a single particular stable value product issuer, the manager of the pool will bundle together stable value products from a number of different issuers, and then credit a blended interest rate to the funds invested in the pool. Spreading the assets among multiple issuers in this way provides diversification of credit risk. Also, by investing in such pooled accounts, small plans are often able to obtain higher yields than would otherwise be possible. One disadvantage of this approach is that there is no credited rate declared in advance. Rather, interest is calculated and applied retrospectively. Also, most of these products do not comply with securities law and state insurance law requirements that must be met to offer them to employers operating plans under IRC Section 403(b).

There are a small number of providers that continue to offer a product to defined contribution plans that at the individual investor level is similar to a series of bank certificates of deposit (CDs). Investors allocate all deposits for a given time period, or window, to a particular CD tranche. All of the deposits made in the window receive a specified rate through maturity. The products have a perception of fairness, but that is significantly offset by complexity. Participants see many different "buckets" for their investments, and retirement plan administrators struggle to record keep all of the various generations of CDs.

Nonstable value investments are still available as the fixed option in some plans. They may include bond mutual funds, money market funds, bank savings accounts, or credit union accounts. They often suffer from one of two disadvantages. In the case of a bond mutual fund, there is no stability of principal. Assets can lose value. This flies in the face of participant demand for stable value investing. In the case of money market funds, credit union accounts, or savings accounts, returns are usually lower over a full market cycle.

The customers who purchase stable value products have been predominantly employer-sponsored retirement plans. Today, stable value products are used mostly to fund defined contribution plans. Stable value products lost their appeal to defined benefit plans in 1992, when the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued an accounting opinion that requires that investments used to fund such plans typically be held at something called "fair value," a shorthand in most cases for market value. This removed the ability of defined benefit plans to capitalize on the stable value aspect of these products.

Stable value accounting was confirmed for defined contribution plans with the AICPA's Statement of Position 94-4, which essentially states that defined contribution plans may hold benefit-responsive contracts at book value if they meet certain requirements. More recently, this position was confirmed by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB), in Statement of Position AAG-INV-1. In essence, a defined contribution plan can hold assets at book value, and thereby avoid the fluctuations and uncertainties of changes in market value, if participants can be confident of receiving plan benefits at book value. In this case, book value is based not on the fluctuation of value based on market conditions, but on the interest rate credited to participant deposits.

- For-profit employers.

Private corporations usually offer plans with an Internal Revenue Code (IRC) Section 401(k) feature. Many similar plan types exist. Most would be eligible for stable value products.

- Not-for-profit employers.

Teachers, health care workers, and other not-for-profit workers often participate in IRC Section 403(b) plans. These are eligible for some stable value products, but not all. A provider must offer certain features to comply with state insurance law and securities requirements.

- Governmental employers.

Governmental employees (other then federal workers) participating in an IRC Section 457(b) deferred compensation plan may use stable value products much like participants in a 401 (k) plan.

- Mixed-plan structures.

It is not unusual to see an employer offer several plan types to employees when they are eligible for multiple plans. This may occur, for example, when a not-for-profit also has status as a governmental entity. A plan might have a 401(k), 457, and 403(b) plan. Stable value may be used by each, but there may be restrictions on commingling the invested assets.

- Taft-Hartley plans.

As a rule of thumb, a Taft-Hartley plan may find stable value useful if it is more like a defined contribution plan in structure than a defined benefit plan.

- Other potential buyers.

Some of the buyers that have approached stable value providers looking for protection of principal on products have included foundations and endowments, managers of general treasury funds, municipal bond issuers, nuclear decommissioning trusts, and others. In general, these situations are limited by the availability of book value accounting to benefit-responsive arrangements, and by provider willingness to offer the requested features. However, there has been some success providing products with features similar to stable value products in other venues, such as short-term funding pools and for foreign entities.

As previously noted in this chapter, there are many variations of features from one stable value product to another. However, there are a few areas that are virtually universal.

Though almost all products have some commonality in the way that they credit interest to participant accounts, such as daily interest crediting and a 365-day year, there are differences by product type. The most significant differences for each of the major product types still in use are described in Table 63.4.

Some products announce a rate to participants in advance of when it is credited. This is often an attractive feature for plans and their safety-conscious participants. Pooled funds do not use this approach. Rather, they credit interest after the fact when the blended return has been calculated.

Rates may be periodically reset. While pooled funds change rates daily, and GIC rates don't change at all (absent some unique contract forms), most other options use a quarterly, semiannual, or annual rate adjustment. For 403(b) plans, rates generally may decrease no more frequently than annually.

Products may have minimum guaranteed rates. These are usually specified percentages, but may be tied to an external reference benchmark, or to a formula. Guarantees may be lifetime or for a specified time period.

Table 63.4. Typical Interest Crediting Approaches by Stable Value Product Type

General Account Portfolio | Traditional GIC | Separate Account GIC | Synthetic GIC | Pooled Fund | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Rate declaration in advance? | Generally, yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

Rate change frequency | Periodic at issuer's discretion based on competitive landscape | None, except in unique constructs | Quarterly, semiannually, or annually | Quarterly, semiannually, or annually | Daily, in arrears |

Minimum guarantees | Lifetime; annual; periodic | Lifetime at a specified rate | Lifetime, often of principal; periodic sometimes higher | Lifetime, often of principal; periodic sometimes higher | No, but underlying contracts usually have guarantees |

Experience rating | Not explicitly to a single plan | Generally, no | Yes, over asset duration | Yes, over asset duration | Not explicitly to a single plan |

Termination date | None | On a specific date or dates | None | None | None |

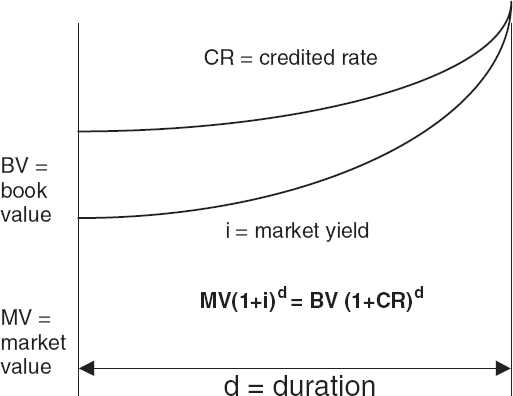

When the interest rate is periodically reset, it may be at the discretion of the provider, or by formula. In separate account and synthetic GICs in particular, there is a relatively standardized industry approach:

where

MV = The current market value of assets held in the separate account or trust under the synthetic.

BV = The book value of assets. Note that this should parallel the sum of participant balances, and reflects net deposits and withdrawals carried forward at the credited rate. It is not the book value of the underlying fixed income instruments.

i = The yield currently available on invested assets. Often an index yield is used.

d = The duration of the invested assets.

CR = The new credited rate to be used for participants.

The intent of the formula is notionally to spread the difference between the current market value and book value of assets over the duration of assets (similar to defeasance of a known liability). It is a notional approach only, in that market value and book value will never be equal, except by coincidence, but serves as an effective and fair way to smooth returns over time.

Figure 63.2 illustrates this approach graphically.

The act of periodically adjusting rates based on plan cash flows and investment performance is often referred to as "experience rating," though sticklers go a bit further and define contracts where rates change based on cash flow experience as "experience rated," and those that change based on investment performance as "participating."

There are a few additional considerations with regard to interest crediting. The first is that when there are multiple products backing a stable value option, there needs to be a methodology for blending the rates on the different products. A simple averaging approach is usually enough, and some way to incorporate into subsequent rates any current difference that has resulted from poor prior guesses.

The second is ensuring that the stable value providers can connect to the trading and administrative systems of the record keeper. Most record keepers today work using a daily valuation system. The provider needs to produce a daily asset value. Alternatively, the provider can calculate a daily interest rate factor in advance, and use that to process a series of asset valuation factors.

A stable value issuer assumes a certain level of risk by making a credited rate guarantee to the contract holder. To help manage this risk, the issuer may include contract provisions within the stable value option specifying how frequently, and in what amounts, funds may be deposited to or withdrawn from the contract.

Deposits

When the issuer and plan sponsor enter into a contract, they will negotiate limits as to the aggregate amount and timing of new deposits. For example, the issuer may agree to a maximum deposit amount, often referred to as a "door" or "cap" provision, and the deposit period is generally known as the deposit "window." There may be a specified minimum deposit amount as well, known as a "floor."

The purpose of these deposit limitations is to help the issuer manage its interest rate risk. If market yields decline and the plan sponsor or participants are able to obtain an above market rate by depositing funds into the stable value option, this could result in a marked increase in deposits. Since the investments purchased with these funds will offer the issuer a lower yield, there will be downward pressure on the credited rate in the case of experience-rated products, and downward pressure on investment margins in cases where the insurer has guaranteed a fixed credited rate. Deposit limitations are much more prevalent in products with stronger guarantees, such as traditional GICs.

Withdrawals

In contrast to deposit restrictions, withdrawal restrictions help the issuer control its risk in the event of volatile or rising interest rates. When interest rates rise, the issuer of a stable value product offering a guaranteed fixed credited rate could face capital losses if the contract holder or participants elect to transfer funds out of the stable value option and into other investment options offering a higher yield.

Participant withdrawals for plan benefits—for example, retirement, death, disability, termination of employment, interfund transfers, loans, or emergencies—are generally not limited. Participants don't generally withdraw funds for these purposes simply for arbitrage. However, participant withdrawals for nonbenefit purposes, or sponsor withdrawals, are usually limited.

A market value adjustment provision limits the plan's ability to transfer funds out of the stable value option at book value in times of volatile interest rates. A provision of this type requires an adjustment to amounts paid out to approximate the changes in market value of the securities underlying the provider's asset portfolio backing the option. A book value "corridor" specifies the maximum percentage of a contract's book value (e.g., 20%) that the contract holder may transfer in a given year without a market value adjustment. The "corridor" approach is often also used as a way of limiting withdrawals paid for employer events, such as layoffs.

Competing fund restrictions also help manage disinterme-diation risk by requiring that the plan sponsor not offer another fixed income investment option (such as a bond mutual fund or money market fund) alongside the stable value option. An alternative or supplement to the competing fund restriction would be an "equity wash" provision. Under an equity-wash provision, alternative fixed income investment options could be available, but participants would be unable to transfer money directly from the stable value option into these options. Instead, the money would have to be transferred to another fund involving some form of market risk (e.g., an equity mutual fund) for some period of time (most commonly 90 days) before it could be transferred to another fixed income option. This element of market risk helps prevent participants from arbitraging across the various available credited rates and allows the provider to credit a higher interest rate.

If a plan sponsor's stable value investment option is supported by a number of stable value products, there will be a withdrawal hierarchy specifying the order in which the various contracts may have funds withdrawn from them. The withdrawal hierarchy is included in the contract, and is agreed upon at the time the contract is underwritten. Examples of withdrawal hierarchies include last in, first out (LIFO), first in, first out (FIFO), net pro rata, and gross pro rata. In a LIFO contract, the amount of any withdrawals in excess of current deposits and cash flows from maturing contracts will be taken from the contract with the most recent effective date. FIFO contracts make these withdrawals from the contract with the earliest effective date. In net pro rata contracts, withdrawals in excess of deposits are taken from each contract in proportion to the percentage of stable value funds held in that contract, while a gross pro rata hierarchy places all current deposits in the contract with the most recent effective date, and then makes all withdrawals on a pro rata basis.

Stable value products may have a specified maturity date, the way that a GIC matures after a certain number of years like a bank CD. However, most stable value products work as evergreen structures. That is, they don't mature on a specific date. The provider must then allow the contract holder one or more ways to exit the contract.

In this event, there will often be an adjustment to reflect any change in the market value of the underlying assets. For example, if interest rates have risen significantly since the deposits were made, the contract holder will likely receive less than book value (that is, the amount of any deposits plus the interest credited under the contract) in the event of early withdrawal.

The difference between the book value and the value received, or "market value," is usually called the market value adjustment (MVA). Two frequently used methods for an insurer to administer the application of a market value adjustment are (1) to maintain two accounting records (one for book value and another for market value) or (2) to apply a market value adjustment formula to the amount of any withdrawals. Other methods might include the actual sale of underlying assets or the assignment of those assets to the plan sponsor.

Market value adjustment formulas may be either oneway or two-way. One-way formulas pay the lesser of book value or the market value-adjusted amount (that is, only negative adjustments are allowed), while two-way adjustments pay the market value-adjusted amount regardless of whether the adjustment is positive or negative.

Under certain circumstances, the contract holder may be able to receive book value at contract termination. Book value settlement options allow the contract holder to elect to receive the principal and interest guaranteed by the contract provided that the balance is paid out over a specified period of time (e.g., five years). An alternative approach is to allow a certain percentage of the contract to be withdrawn at book value every year. A specific subset of this category is used for pooled funds. Under a "one-year put," all funds may be withdrawn at book value within 12 months.

A third option may be available in certain circumstances, usually in a product that invests in publicly traded securities, especially for larger plans. This might be the case, for example, with a separate account or synthetic GIC. This type of transfer arrangement is called a "transfer-in-kind." With a transfer-in-kind, the successor provider after termination receives the assets directly from the prior provider in kind. The successor provider may then decide to sell assets in the portfolio to adjust to a desired investment mix. If the securities held by the prior provider prior to transfer are not held solely for that sponsor, a methodology must be developed to prorate the holdings, maintaining the underlying asset characteristics, and allowing for transaction efficiency (e.g., to maintain round lots for trading).

Finally, many stable value products contain annuity purchase provisions, allowing the plan sponsor to use funds from the contract to purchase retirement annuities for individual plan participants. If there are annuity purchase provisions in the contract, guaranteed purchase rates will generally be specified, and purchases made at book value.

Stable value products sold by insurers are traditionally issued in the form of an unallocated group annuity contract. The contract is most often issued to the plan trustee, but may also be issued directly to the employer or plan sponsor. As an insurance product, the contract form will usually contain guaranteed annuity purchase rates, and must be approved by state insurance regulators. In an unallocated contract, the issuer maintains a record of the aggregate value of the funds invested under the contract, but no record of individual participants' account balances. Instead, the plan itself or a third-party administrator (TPA) typically keeps track of participant balances using the information provided by the issuer (e.g., credited rates), mails participant statements, and performs other administrative functions.

The contract could also be issued as a trust agreement if the arrangement is with a bank, trust company, or pooled fund manager. In a trust agreement, plan contributions are provided to an investment trustee, which is distinct from the plan's master trustee. The investment trustee then has responsibility for investing the funds, accumulating earnings, and providing funds to the plan's master trustee to pay participant benefits. The trust agreement is a flexible structure (money may be invested in commingled trust funds or in separate investment contracts, and in equities as well as bonds) and is not subject to the approval of state insurance regulators.

The funding agreement and other "unbundled" approaches were developed by insurers in an effort to match the flexibility of the trust and to avoid some of the negative associations that buyers have with annuities. These arrangements generally do not include annuity purchase rates, but allow the plan sponsor to take advantage of the insurer's investment expertise.

There are also "split-funded" structures where the plan sponsor utilizes both a group annuity contract and a bank arrangement as part of the stable value option.

Because the buyers of stable value products are adjudged to be sophisticated investors, these contract forms usually do not need to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)—a distinct advantage from the issuers' perspective, since filing a product with the SEC is a lengthy process requiring a great deal of effort and legal expense. However, the nature of certain plans, such as those established under IRC Section 403(b), do require that their investment options maintain certain minimum characteristics.

Buyers of stable value products face a number of considerations if they are to maintain a plan that keeps their participants satisfied and reflects the nature of their plan design, industry characteristics, and workforce demographics.

Much like a similar concern in the fixed income markets, sponsors want to avoid overexposure to the credit risk of a single issuer. Buyers will often diversify their purchases of stable value products to mitigate this risk. If the product is one with a strong guarantee from the provider, then it will be more important to purchase from a top-quality provider, or to diversify well across providers. In experience-rated products where the performance of the underlying instruments is passed through to the plan, diversification of invested assets is more critical than diversification by issuer.

In traditional GICs, then, the diversification concern ought to be at the issuer level. In separate accounts and synthetics, by contrast, look to the underlying fixed income portfolio. In general account portfolio rate products, both are important. In a pooled fund, the level of focus on each element will depend on the mix and characteristics of the underlying contracts.

In fixed-term contracts (traditional GICs), it is also important to diversify across time (that is, by purchase date and maturity date), so that not all purchases or sales are made in the same rate environment.

In order to obtain a competitive rate from an issuer, a buyer often has to have a large enough placement (e.g., $5 to $10 million) to interest a group of issuers. This is a concern that buyers often must manage against their other objectives of diversifying by issuer, or in the case of fixed-term products, by frequency of purchase or maturity date.

Most products should pretty routinely contain provisions to pay standard participant-directed benefit withdrawals at book value, as allowed by the plan. These benefits would typically include:

Retirement

Death

Disability

Termination of employment

Emergency or hardship

Loans

Interfund transfers

Annuity purchase

If there are multiple contracts, a plan should be sure to establish a withdrawal hierarchy and to coordinate withdrawal provisions across different products.

If the plan has the potential for volatile cash flows, either because deposits are irregular or withdrawals are unpredictable, holding a cash "buffer" fund often makes sense. A cash buffer is a shorter-term fixed income option or money market fund used as a shock absorber against volatile deposit and withdrawal patterns. The buffer is targeted at a certain level. When that level is significantly exceeded, the excess is deposited to the core stable value contract(s). When there is a significant shortfall, a withdrawal is made from the core stable value contract(s) to replenish the buffer. Typical buffer targets are in the 2% to 5% range. Returns on buffers are blended with core product returns to produce a single blended credited rate for use with participants.

This is an area that requires particular focus, both to assure that the provisions are fair and to be sure that they reflect the likely needs of the employer.

As noted, sponsor-directed withdrawals, such as might occur at the termination of the contract, are usually subject to contractual limitations or adjustments so that the provider may be assured of a longer-term investment horizon and generate a higher corresponding interest rate. The construction of these limitations or adjustments ought to be designed to reflect the economics of the underlying assets, plan cash flows, and interest rate movements, rather than set arbitrarily or with undue discretion by the provider. Table 63.5 denotes some of the typical limitations and adjustments frequently encountered, by product type.

MVAs vary widely by contract type and provider. Where they do come into play, the contractual provisions describing them need close scrutiny. In a general account portfolio, assets are invested in a large pool, and no buyer owns an individual interest in any investment in the insurer's general account. Rather, they own a promise from the insurer to pay a particular rate, which may change. MVA formulas are intended to replicate the buyer's theoretical share in the underlying pool by proxy.

Many contracts, especially those that are evergreen in nature, may have old formulas or somewhat dated provisions reflecting the market environment at time of purchase. Better or newer formulas will have these elements:

A defined formula rather than an offer to provide a value upon request.

Direct reference to nonmanipulable variables, such as an index or base rate.

A proxy reflective of the characteristics (e.g., duration and quality) of the underlying assets.

Specification of any fees or "haircuts" used by the provider in the formula to defray liquidation or unrecovered sales expenses, or the lack of liquidity of some of the assets.

Book value settlements typically contain similar issues:

The duration of payout should correspond to that on the underlying assets.

The interest crediting calculation and benefit liquidity provisions during settlement should be specified. Specifically, issuers may assess a fee or rate reduction during settlement. This fee or reduction needs to be disclosed and reasonable.

A transfer-in-kind provision needs to provide some information about how the pro rata share of transferred assets is calculated, and needs to parallel the quality, duration, and other characteristics of the underlying portfolio in establishing a subset of that portfolio for transfer. Illiquid assets are difficult to transfer, so provision needs to be made for alternatives or substitution.

Table 63.5. Typical Plan Sponsor Exit Limitations and Adjustments to Stable Value Products

Product Type | Market Value Immediately | Book Value Settlement | Other |

|---|---|---|---|

Traditional GIC | Usually no market value available. If so, based on a formula. | NA-these contracts already have a specified maturity date | Not usually |

General account portfolio rate product | Usually yes, by formula | Yes, usually over a set time period meant to reflect general account asset duration | Deferred sales charges may apply on older contracts |

Separate account | Since invested in publicly traded securities, market value directly determinable using prorated asset share | Yes, over asset duration | Transfer-in-kind may be available |

Synthetic GIC | Since the assets are held on the buyer's behalf in a trust, assets may be sold and the proceeds paid to successor provider | Often yes, over asset duration | Transfer-in-kind typical |

Pooled fund | Not usually available | "One-year put" | One-year put pays assets within 12 months at book value |

A payout option that is almost entirely unique to pooled funds is something often referred to as a "one-year put." Under this arrangement, investors in a pooled fund may withdraw assets at book value, but may need to wait up to one year to receive the proceeds. Some providers qualify this feature by allowing immediate withdrawal if the remaining pool investors aren't damaged, or depending on the size of the queue waiting for withdrawal. A few contain a "force majeure" provision that would further limit withdrawals in extreme market conditions.

A frequent purchase concern of stable value buyers is how to effect a transfer from one record keeper or issuer to another if the stable value option changes hands. Some considerations are:

- Transfer at Full Value

Sponsors want comfort that, if there is a market value adjustment or deferred sales charge with the prior provider, participants won't lose value in their stable value option. One protection that sponsors have used is not to describe the stable value option as "fully guaranteed," and to note in participant disclosure that there may be times when participants won't receive 100% of underlying asset value. Another, more practical approach is that there is a ready market from successor providers in so-called market value make-up contracts. These are contracts under which participant book value is maintained, and under which the successor provider bears a portion of any loss, or participants receive a reduced rate in the future to defray the costs. This approach is relatively common.

- Delays in Payment

When a book value settlement or one-year put provision is engaged, sponsors want to smooth the transition from one provider to another. The usual way that this is accommodated is to maintain the prior account and new account side by side, to limit deposits and withdrawals to one of the two accounts, and to blend the rates to produce a single rate for participants.

- Reinvestment Risk

Another concern is that any adjustment or delay not adversely affect participant credited rates. If a market value formula is fair, two-way, and a good reflection of underlying economics, it should not present an issue. With fixed income instruments, there is an inverse relationship between interest rates and market value. When market values decline, the proceeds may be reinvested at higher rates, and participant credited rates should be unaffected.

In the situation of a one-year put, this feature may work to either the benefit or detriment of participants. If rates rise, the sponsor may withdraw assets at book value in a high-rate environment and participants receive an increase in rate. If rates decline at the time a sponsor exits a contract, a book value transfer will decrease participant credited rates.

Table 63.6. Pros and Cons of Various Sponsor Transfer Provisions

Provision | Pro | Con |

|---|---|---|

Actual market value | Convenient and efficient | Need to find market value make-up provider |

MVA | If formula is economic, maintains rate for participants | Poor proxies can throw off rate; transaction costs of trading can reduce rate |

Book value settlement | Maintains book value | Need to coordinate multiple contracts |

Transfer-in-kind | No approximation required | Complex transaction best suited to large clients |

One-year put | Easy to understand, and good protection in a rising rate environment | Rate decrease in declining rate environment |

Table 63.6 outlines some of these considerations.

Plan Structure and Potential Plan Changes

One of the most important objectives of a plan sponsor managing a stable value option is to match the funding vehicles and the portfolio structure to the character of the particular plan and its participants. Here are some examples:

A plan with high turnover of its employees might expect significant negative cash flows from its employees—it might want to maintain a liquid portfolio or keep a substantial portion of assets in cash.

A small plan with assets concentrated with one or two highly paid individuals who could conceivably retire or leave the firm may invest differently than one with more diversified account balances.

A plan with many investment options and liberal transfer restrictions can expect higher volatility of participant cash flow than one without these features.

A plan for a company undergoing merger and acquisition activity or expected layoffs may have different needs than an established stable plan.

Duration

A stable value portfolio, just like other fixed income portfolios, has a duration, and it can be calculated in a similar manner. Fundamentally, duration measures the responsiveness of the stable value option's credited investment rate to changes in external market interest rates.

Table 63.7. Typical Stable Value Option Investment Characteristics

Characteristic | Range | Typically Observed | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

Duration | 2-5 years | 3 years | Shorter duration = lower yield, but better rate tracking |

Quality | A to AAA | AA | Safety-oriented investment generally leads to higher quality |

Liquidity | 2%-5% cash buffer; benefit withdrawals at book value | 3% buffer | Affirm that contract liquidity provisions are fair and balanced |

Generally, in a normal, positively sloped yield curve environment, the credited rates on longer-term fixed income instruments are higher than those on shorter instruments. Absent any other factors, this might mean at first blush that a buyer of stable value instruments would prefer to have a long portfolio. Curiously, however, the duration of most stable value funds tends to be around three years, whereas the duration of the fixed income market, as approximated by the Lehman Brothers Aggregate Index, is between four and five years.

Are GIC and stable value fund managers giving up incremental yield unnecessarily, or is there some other issue driving this apparent duration decision? It could result from a number of factors:

Rate tracking. The contract holder may want the overall return to move very quickly in the direction of prevailing interest rates; a portfolio with a three-year duration would be more responsive than one with a four- or five-year duration.

Conservatism. Stable value funds are managed to be low risk; maybe most stable value fund sponsors are conservative.

Liquidity bias. Some sponsors may wish to avoid the perception of being "locked in" to a contract or option.

Utility. Sponsors may receive more benefit from flexibility than from a high rate. As one sponsor of a very large plan has noted "My return is asymmetric. If I get participants a few extra basis points, no one cares. If participants think something has gone wrong with the plan, I get yelled at."

Liquidity and cash buffers. To manage plan changes and their effect on stable value option cash flow, as well as to maintain liquidity, many plans will maintain a cash buffer in their stable value option. The cash buffer works by receiving all deposits from participants and maturities of any existing maturing contracts, and by paying all withdrawals. The net amount available for investment is then deposited to a current stable value product. This simplifies plan management in that a plan does not need to approach several vendors to pay withdrawals, or can get better interest rate quotes from buyers due to reduced expected volatility.

Asset quality. Generally, there is an inverse relationship between the quality of fixed income assets backing a stable value option and their current expected yield. A plan will need to decide where on the spectrum of quality and yield it would like to be. Although there are outliers, most plans operate in the AA range, most likely reflective of the stable value option being a perceived safety-oriented investment.

There is no one instrument that provides the highest possible interest rate, the highest quality, and immediate liquidity. A plan will need to decide which combination is best, based on its own characteristics. Table 63.7 summarizes some of the considerations in these trade-offs.

Book value accounting and the benefit responsiveness that makes it possible are probably the primary reasons that sponsors buy stable value products today, mainly because most buyers are now defined contribution plans. A plan qualifies to use book value accounting if it meets AICPA guideline 94-4 and FASB Statement of Position AAG-INV-1. The benefit of book value accounting is that even if the market value of a stable value portfolio changes over time, the plan is allowed to credit participant accounts based on the book value (that is, based on the rate credited on its investment options). This allows the participants to avoid the day-to-day fluctuations of the market and see a steady stable return over time. Because of its fundamental impact on plan reporting to participants, a plan should be very careful to maintain its eligibility for book value accounting.

Reporting Needs

A plan needs to keep track of its investments and manage the various aspects of its portfolio, such as distribution by investment provider, duration, upcoming maturity amounts, liquidity, and so on. It should make whatever arrangements are necessary with its provider to produce periodic reports with the information it needs.

Participant Disclosure

A sponsor should adequately disclose situations to participants under which a participant may access their account at book value, and those under which access is limited.

Just as plan sponsors have many issues with managing stable value products, so do issuers.

Stable value products generally break down into three broad categories:

Fully guaranteed contracts or contracts with significant elements of a guarantee (e.g., a GIC or general account portfolio rate product).

Actively managed products such as a separate account or synthetic GIC, under which guarantees tend to be low and most investment performance is passed on to the contract holder over time.

Pooled funds, where the issuer is assuming neither guarantee risk nor active fixed income management responsibilities, but is responsible for the construction and operation of the pool.

(Note: It is not uncommon that a pooled fund operator will also have a subsidiary investment adviser manage plan assets, subject to restrictions on fees to avoid a conflict of interest.)

Each of these types exhibits different characteristics and creates different corresponding considerations.

An issuer needs to decide what type of investments to purchase to back its stable value products, and how those assets will be managed. Considerations include:

Asset type

Asset quality

Asset duration

Liquidity elements and cash position

Investment optionality and derivatives usage

Active or passive management

Fully guaranteed contracts are typically issued by an insurance company, and backed by a segment of the insurer's general account. Assets often include the full spectrum of fixed income, including publicly traded securities, private issuers, commercial mortgages, mortgage- and asset-backed securities, and even a few other instruments. Assets are often held for a longer duration, such as five years. The portfolio usually contains adequate cash liquidity to pay net withdrawals, since it is such a large pool. Liquid assets (publicly traded securities) are often actively managed, while illiquid investments are held to maturity.

Assets are usually held in publicly traded securities in a well-diversified portfolio, and, since returns are passed on to the contract holder over time, construction reflects sponsor preferences. Duration is often in the three- to five-year range, and asset quality AA. Assets are actively managed against an external benchmark. Derivatives use is limited to hedging and replication. Liquidity is not typically an issue given that securities can be sold on the public market.

A pooled fund operator usually doesn't hold the assets backing the pool, but rather diversifies by issuer of the GICs, synthetics, separate account, and other instruments that comprise the pool. A pooled fund will also look to the investment guidelines of the underlying assets to appropriately diversify.

An important subset of investment management is the management of assets against liabilities. This involves managing the cash flow of the assets to meet short-term needs for payments or maturities, managing the duration of the assets so that the value of the underlying portfolio moves in tandem with that of the liabilities, and managing convexity (a portfolio's tendency for its duration to shift over time as interest rates change).

Disastrous results can occur if a portfolio of investments is not properly matched to its corresponding liabilities. If rates rise dramatically, purchased assets may have a market value well below that granted to the buyer, and untimely liquidation of those assets could result in a significant loss.

Asset liability matching is most important in fully guaranteed products or products with substantial guarantees. Issuers of these products should match:

The maturity schedule of assets and liabilities.

The duration (average maturity weighted by present value of maturities).

Nonlinear changes in value (e.g., on the asset side, the tendency of mortgage pass-through securities to shift in value based on prepayment activity; on the liability side, any options to the sponsor to redeem assets early at book value).

Almost all experience under these products is passed through to the plan over time through changes to future credited rates, so asset-liability matching, except in extreme circumstances under which guarantees are breached, is in essence, automatic from the issuer's perspective. However, matching the investment characteristics to the plan's expected cash flow dynamics is critical to buyer satisfaction, even if a mismatch would not violate any explicit contractual guarantees.

Regardless of the type of product issued, a provider needs to underwrite the risks of changes in plan cash flow activity, primarily the benefit-responsive risks it is taking on.

The benefit-responsiveness risk is the risk that the stable value product used has to pay out more in benefits than expected at an inopportune time, mainly after interest rates have risen so that the asset portfolio backing the product is worth less than the value of the benefits it must pay. In essence, the issuer has issued the equivalent of a financial option to the buyer, though one contingent on certain preagreed and presumably nonselectable events. Its risk is that the option is exercised in an adverse environment.

The risk is driven by participants' rights to withdraw funds at book value, regardless of the prevailing interest rate environment, for certain events such as retirement, death, disability, termination of employment, or transfer out of the stable value option to other available participant investment options. A similar cash flow-related risk is that a participant may deposit money to the issuer at the wrong time (e.g., after rates have dropped).

Some of the tools an issuer uses to underwrite benefit responsive risks are:

An analysis of the plan's structure and provisions.

An analysis of the plan's participant base.

Historical deposit and withdrawal activity.

Use of a cash buffer fund.

Examination of the withdrawal hierarchy.

Competitiveness of the plan's interest rate.

Historical plan allocation of fixed/variable assets.

A look at what other investment vehicles fund the stable value option.

In a fully guaranteed product, underwriting is critical to protecting the insurer's assets. In actively managed products or pooled funds, underwriting is also important. Since performance ultimately accrues to the benefit or detriment of plan participants, good underwriting can prevent one group of participants from adversely affecting another. In other words, it protects generational equity. Even in a pooled fund, underwriting is important so that one plan doesn't impact others negatively. In fact, pooled funds often contain an additional underwriting feature, a maximum plan ownership in the pool to ensure some level of diversification.

Table 63.8 illustrates typical risks under a defined contribution plan, and controls that are often used as protections against these risks.

Issuers of stable value products must comply with a wide variety of laws, regulations, and accounting requirements, depending on the typical product(s) issued. Requirements include:

- State law.

Insurance company products are issued in most states as group annuity contracts, and sometimes as funding agreements. State insurance law applies with regard to the requirements for these particular forms, and for the issuance of contracts in general. There are also state laws that apply to the marketing of insurance products.

- Securities law.

Most stable value products are exempt from state or federal securities registration and sales requirements by virtue of the fact that they are sold to qualified retirement plans, which are adjudged to be sophisticated investors. However, state and federal antifraud laws do apply to the marketing of these products. Stable value products issued to 403(b) plans have unique securities law requirements to meet.

- ERISA.

The Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 (ERISA) governs some of the requirements relating to how a stable value product can be sold and how the insurer may manage the underlying assets. If ERISA issues do arise, they are usually with respect to potential conflicts of interest.

Table 63.8. Typical Stable Value Option Underwriting Risks and Controls

Risk | Typical Control |

|---|---|

Participants are laid off after rates have risen, and request massive withdrawals at book value under "termination." | Contractual provision to limit payments at book value in the event of "employer-initiated" events such as layoffs, early retirement incentive programs, spin-offs, divestitures, etc. |

Participants transfer assets out of the stable value option to another investment option. | Issuers usually accept this risk with regard to equity options, but for "competing" options, those that are fixed income or short term in nature or have a principal guarantee, do not allow transfers or allow them only with a requirement that transferring participants maintain transferred assets in an equity account for a minimum time period (an "equity wash" provision). |

Hot money issues: the plan has many retired participants still in the plan that can take their money at any time at book value. | Issuers generally underwrite for the risk rather than controlling it, and set fees accordingly. |

The plan sponsor coaches participants to leave the stable value fund. | Anticoaching provisions, relieving issuer of obligations if coaching is used. |

Plan deposits are higher than expected after rates drop, or lower than expected after rates rise, requiring issuer to credit an inappropriate rate compared to market rates. | Minimum and maximum deposit requirements. |

Plan withdrawal hierarchy allocates all withdrawals to current provider (LIFO) and current provider gets high withdrawals. | Issuers often underwrite this risk, as it is short term in nature. Deposit floors also provide some protection. |

Trust law. Bank and trust products are subject to banking and trust laws, and some to requirements of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC).

Issuers of stable value products of all types have made mistakes. These mistakes are useful to remember so as not to repeat them.

Lesson 1: Forward Commitments

Up until the late 1970s, interest rates had remained fairly level for decades. In order to obtain higher rates, it had become common practice to commit forward on investments, that is, to buy investments to back a liability even before corresponding liabilities (at the time, GICs) were sold. When rates spiked in the late 1970s, this left insurers holding old investments with below-market rates.

Lesson 2: Open Windows

In the 1980s, the competition to issue GICs to large plans was fierce. On more than one occasion, insurers agreed to accept an unspecified amount of deposits, dramatically underestimated the deposit amounts as rates fell, and were forced to credit an above-market rate on the excess dollars deposited.

Lesson 3: Overinvestment in the Wrong Assets

Another result of competition has been occasional over-concentration of insurer assets in certain asset classes to achieve a rate advantage. When those assets, such as commercial mortgages, mortgage pass-through securities, or Asian debt later fell into cyclical downturns, insurers with overconcentration in these areas suffered.

All three of these errors can be looked at as different versions of the same issue; slowly becoming inured to the potential risks of overinvesting in assets or mismatching assets and liabilities.

Actively managed products present fewer guaranteed risks to issuers, as experience is passed through to the plan. However, even with these products, issuers have made mistakes.

The biggest of these was providing options to the sponsor to exit the contract early at book value. When this happened, losses were so substantial that one issuer of products of this type became insolvent.

One issue for pooled funds has been one of trying to keep up with rising interest rates. Not so much an error as a structural issue, many pooled funds set up a second pool when rates rose to keep rates competitive. This meant the customers in the "old" pool ended up with a stale rate because they had limited new investment.

Another issue for pooled funds is that by investing in products issued by multiple providers, the risk of at least one problem with an issuer is increased. Sometimes, when these issuers had problems, pools have had to freeze or otherwise encumber access to assets. It didn't cause losses to customers, but did cause some inconvenience.

In a vacuum, there is no right or wrong vehicle that a plan should use to fund its stable value option. However, a plan can make an assessment as to its best fit based on its characteristics.

Table 63.9 summarizes relative advantages and disadvantages of different vehicles, and profiles some typically good customer matches.

There are a number of factors reinvigorating interest in principal-protected products:

- Higher interest rates.

Although interest rates are still well below their historical acme, every time rates begin to rise, an interest in stable value products reappears.

- Fee transparency.

The fee structure on some newer stable value products is easier to explain than on older products. In an environment where buyers more than ever want to understand fees, these products are attractive.

- Demographics.

The Baby Boom is a fundamental demographic affecting a broad swath of U.S. consumption. One aspect of how it affects retirement investing is that defined contribution plan participants, in an environment where they are ever more responsible for their own future retirement needs, have substantial accumulated assets. Principal-protected products become attractive as they allow investors to protect these accumulated assets. Similarly, managing income is an objective of increasing importance to aging defined contribution plan participants. Principal-protected products can guarantee an income stream.

Some of the emerging uses for stable value include:

- Managing postretirement income.

Aging Baby Boomers are shifting from an accumulation mind-set to a lifestyle mind-set: "What can I do with my money, and how do I protect it?" Stable value concepts help with both aims.

- Health Reserve Account (HRA) funding.

Postretirement health care benefits are becoming an increasingly growing concern both for working employees and their employers. Vehicles are developing to assist in the pre-funding of these obligations. Principal protection may be a valuable element of prefunding approaches.

Table 63.9. Comparison of Stable Value Funding Vehicles

Fully Guaranteed | Actively Managed, Experience-Rated | Pooled Funds | |

|---|---|---|---|

Benefits | Higher minimum guarantees | Control over investment strategy | Quicker tracking of external rates |

Higher rate over a full market cycle | Can produce good returns over long term | Broad diversification | |

Economy of scale in purchase of investments | Easy transfer provisions | Easy to understand | |

Protection against credit risk | One-year put good in rising rate environment | ||

Drawbacks | Credit exposure to single issuer Approximations needed to estimate ownership shares Older contracts often contain unattractive provisions | Individual account-no pooling Subject to individual plan cash flow experience | No rate declared in advance Broader exposure to (smaller) credit events One-year put adverse in declining rate environment |

Typical best-fit customer | Plans in need of substantive guarantee | Large plans | Small plans |

Some element of unpredictability in plan cash flows | Some expertise in or desire for setting investment parameters | Little participant interest in credited rates | |

Substantial employer control | Customer sensitivity to ease of understanding rights of transfer | ||

Stable plan cash flows |

Foreign entities. The use of the defined contribution model is spreading in various formats across the globe. Stable value can be an important concept in other countries just as it has been in the United States.

Defined benefit liability defeasance. Although defined benefit plans have decreased in usage, large liabilities still remain, and they are associated with an aging employee and retiree base. Stable value may have a role in defeasing those liabilities.

Retail uses. Although the SEC's position on book value accounting for stable value mutual funds has stymied growth in that area, latent underlying demand may still drive some type of a pooled retail stable value capability.

The attractiveness of stable value products changes with interest rates and regulations, but the underlying driving forces behind stable value—the desire for protection and stability—are fundamental to human nature. Stable value is likely to endure in some form for a long time to come, though the particular manifestation may vary from what stable value looks like today.

Stable value investment options provide a flexible, adaptable funding vehicle for defined contribution participants saving for retirement. Because they tap into fundamental human concerns about protection and control, they are effective with savers across the retirement savings spectrum, regardless of age or income. Because of this same versatility, they are also emerging as viable alternatives for investors approaching or in retirement, and have potential broader application to any venue in which a group of individuals with common characteristics are saving for a future need or are managing an income stream, and wish to do so with some stability.

Caswell, J. R., and Tourville, K. (1998). Managing a synthetic GIC portfolio. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 65-86). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Caswell, J. R., and Tourville, K. (2005). Stable value investments. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 7th edition (pp. 471-485). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gallo, V. A. (1998). Underwriting stable value risks. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 277-300). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Haendiges, H. K., and Keener, E. A. (1998). Traditional GICs. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 19-44). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

LeLaurin, S. F, and Guenther, J. P. (1998). Stable value management. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 327-373). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mercier, J. L., Turco, A. A., Smith, K. J., and Smith W M. (1998). Legal, regulatory, and accounting issues. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 19-44). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Pearce, T. (1998). Buy and hold synthetics. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 87-112). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Rudolph-Shabinsky, I., and Psome, C. J. (1998). Mangaged synthetics. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 113-150). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Smith, K. M., and Koeppel, S. E. (1998). In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Stable Value Investments (pp. 45-59). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.