FRANK J. JONES, PhD

Professor, Accounting and Finance Department, San Jose State University and Chairman of the Investment Committee, Salient Wealth Management, LLC

FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

Abstract: Investment companies include open-end mutual funds, closed-end funds, and unit trusts. Shares in investment companies are sold to the public and the proceeds invested in a diversified portfolio of securities. The value of a share of an investment company is called its net asset value. The two types of costs borne by investors in mutual funds are the shareholder sales charge or loads and the annual fund operating expense. Two major advantages of the indirect ownership of securities by investing in mutual funds are (1) risk reduction through diversification, and (2) reduced cost of contracting and processing information because an investor purchases the services of a presumably skilled financial advise at less cost than if the investor directly and individually negotiated with such an adviser. There is a wide-range of investment companies that invest in different asset classes and with different investment objectives.

Keywords: investment companies, open-end funds, mutual funds, closed-end funds, net asset value (NAV), shareholder fee, sales charge, load, commission, expense ratio, unit trust, front-end load, operating expense, expense ratio, management fee, family of funds, investment adviser, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), Morningstar, Lipper

Investment companies are entities that sell shares to the public and invest the proceeds in a diversified portfolio of securities. Each share sold represents a proportional interest in the portfolio of securities managed by the investment company on behalf of its shareholders. The type of securities purchased depends on the company's investment objective.

There are three types of investment companies: open-end funds, closed-end funds, and unit trusts.

Open-end funds, commonly referred to simply as mutual funds, are portfolios of securities, mainly stocks, bonds, and money market instruments. There are several important aspects of mutual funds. First, investors in mutual funds own a pro rata share of the overall portfolio. Second, the investment manager of the mutual fund manages the portfolio, that is, buys some securities and sells others (this characteristic is unlike unit investment trusts, discussed later).

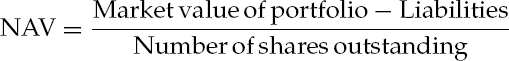

Third, the value or price of each share of the portfolio, called the net asset value (NAV), equals the market value of the portfolio minus the liabilities of the mutual fund divided by the number of shares owned by the mutual fund investors. That is,

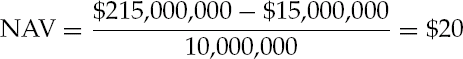

For example, suppose that a mutual fund with 10 million shares outstanding has a portfolio with a market value of $215 million and liabilities of $15 million. The NAV is

Fourth, the NAV or price of the fund is determined only once each day, at the close of the day. For example, the NAV for a stock mutual fund is determined from the closing stock prices for the day. Business publications provide the NAV each day in their mutual fund tables. The published NAVs are the closing NAVs.

Fifth, and very importantly, all new investments into the fund or withdrawals from the fund during a day are priced at the closing NAV (investments after the end of the day or on a non-business day are priced at the next day's closing NAV).

The total number of shares in the fund increases if there are more investments than withdrawals during the day, and vice versa. This is the reason such a fund is called an "open-end" fund. For example, assume that at the beginning of a day a mutual fund portfolio has a value of $1 million, there are no liabilities, and there are 10,000 shares outstanding. Thus, the NAV of the fund is $100. Assume that during the day $5,000 is deposited into the fund, $1,000 is withdrawn, and the prices of all the securities in the portfolio remain constant. This means that 50 shares were issued for the $5,000 deposited (since each share is $100) and 10 shares redeemed for $1,000 (again, since each share is $100). The net number of new shares issued is then 40. Therefore, at the end of the day there will be 10,040 shares and the total value of the fund will be $1,004,000. The NAV will remain at $100.

If, instead, the prices of the securities in the portfolio change, both the total size of the portfolio and, therefore, the NAV will change. In the previous example, assume that during the day the value of the portfolio doubles to $2 million. Since deposits and withdrawals are priced at the end-of-day NAV, which is now $200 after the doubling of the portfolio's value, the $5,000 deposit will be credited with 25 shares ($5,000/$200) and the $1,000 withdrawn will reduce the number of shares by 5 shares ($1,000/$200).

Thus, at the end of the day there will be 10,020 shares (25 −5) in the fund with an NAV of $200, and the value of the fund will be $2,004,000. (Note that 10,020 shares × $200 NAV equals $2,004,000, the portfolio value.)

Overall, the NAV of a mutual fund will increase or decrease due to an increase or decrease in the prices of the securities in the portfolio, respectively. The number of shares in the fund will increase or decrease due to the net deposits into or withdrawals from the fund, respectively. And the total value of the fund will increase or decrease for both reasons.

The shares of a closed-end fund are very similar to the shares of common stock of a corporation. The new shares of a closed-end fund are initially issued by an underwriter for the fund. And after the new issue, the number of shares remains constant. This is the reason such a fund is called a "closed-end" fund. After the initial issue, there are no sales or purchases of fund shares by the fund company as there are for open-end funds. The shares are traded on a secondary market, either on an exchange or in the over-the-counter market.

Investors can buy shares either at the time of the initial issue (as discussed below), or thereafter in the secondary market. Shares are sold only on the secondary market. The price of the shares of a closed-end fund are determined by the supply and demand in the market in which these funds are traded. Thus, investors who transact closed-end fund shares must pay a brokerage commission at the time of purchase and at the time of sale.

The NAV of closed-end funds is calculated in the same way as for open-end funds. However, the price of a share in a closed-end fund is determined by supply and demand, so the price can fall below or rise above the net asset value per share. Shares selling below NAV are said to be "trading at a discount," while shares trading above NAV are "trading at a premium." Newspapers list quotations of the prices of these shares under the heading "Closed-End Funds." Some sources also list the NAV and the discount or premium of the shares.

Consequently, there are two important differences between open-end funds and closed-end funds. First, the number of shares of an open-end fund varies because the fund sponsor will sell new shares to investors and buy existing shares from shareholders. Second, by doing so, the share price is always the NAV of the fund. In contrast, closed-end funds have a constant number of shares outstanding because the fund sponsor does not redeem shares and sell new shares to investors (except at the time of a new underwriting). Thus, the price of the fund shares will be determined by supply and demand in the market and may be above or below NAV, as discussed above.

Although the divergence of the price from NAV is often puzzling, in some cases the reasons for the premium or discount are easily understood. For example, a share's price may be below the NAV because the fund has a large built-in tax liability and investors are discounting the share's price for that future tax liability. (We'll discuss this tax liability issue later in this chapter.) A fund's leverage and resulting risk may be another reason for the share's price trading below NAV. A fund's shares may trade at a premium to the NAV because the fund offers relatively cheap access to, and professional management of, stocks in another country about which information is not readily available to or transactions are difficult or expensive for small investors.

Under the Investment Company Act of 1940, closed-end funds are capitalized only once. They make an initial IPO (initial public offering) and then their shares are traded on the secondary market, just like any corporate stock, as discussed earlier. The number of shares is fixed at the IPO; closed-end funds cannot issue more shares. In fact, many closed-end funds become leveraged to raise more funds without issuing more shares.

An important feature of closed-end funds is that the initial investors bear the substantial cost of underwriting the issuance of the funds' shares. The proceeds that the managers of the fund have to invest equals the total paid by initial buyers of the shares minus all costs of issuance. These costs, which average around 7.5% of the total amount paid for the issue, normally include selling fees or commissions paid to the retail brokerage firms that distribute them to the public. The high commissions are strong incentives for retail brokers to recommend these shares to their retail customers, and also for investors to avoid buying these shares on their initial offering.

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) pose a threat to both mutual funds and closed-end funds. ETFs, which are the subject of Chapter 61 in Volume I, are essentially hybrid closed-end vehicles, which trade on exchanges but which typically trade very close to NAV.

Since closed-end funds are traded like stocks, the cost to any investor of buying or selling a closed-end fund is the same as that of a stock. The obvious charge is the stock broker's commission. The bid/offer spread of the market on which the stock is traded is also a cost.

A unit trust is similar to a closed-end fund in that the number of unit certificates is fixed. Unit trusts typically invest in bonds. They differ in several ways from both mutual funds and closed-end funds that specialize in bonds. First, there is no active trading of the bonds in the portfolio of the unit trust. Once the unit trust is assembled by the sponsor (usually a brokerage firm or bond underwriter) and turned over to a trustee, the trustee holds all the bonds until they are redeemed by the issuer. Typically, the only time the trustee can sell an issue in the portfolio is if there is a dramatic decline in the issuer's credit quality. As a result, the cost of operating the trust will be considerably less than costs incurred by either a mutual fund or a closed-end fund. Second, unit trusts have a fixed termination date, while mutual funds and closed-end funds do not. (There are, however, exceptions. Target term closed-end funds have a fixed termination date.) Third, unlike the mutual fund and closed-end fund investor, the unit trust investor knows that the portfolio consists of a specific portfolio of bonds and has no concern that the trustee will alter the portfolio. While unit trusts are common in Europe, they are not common in the United States.

All unit trusts charge a sales commission. The initial sales charge for a unit trust ranges from 3.5% to 5.5%. In addition to these costs, there is the cost incurred by the sponsor to purchase the bonds for the trust that an investor indirectly pays. That is, when the brokerage firm or bond-underwriting firm assembles the unit trust, the price of each bond to the trust also includes the dealer's spread. There is also often a commission if the units are sold.

In the remainder this chapter of our primary focus chapter is on open-end (mutual) funds.

There are two types of costs borne by investors in mutual funds. The first is the shareholder fee, usually called the sales charge or load. For securities transactions, this charge is called a commission. This cost is a "one-time" charge debited to the investor for a specific transaction, such as a purchase, redemption or exchange. The type of charge is related to the way the fund is sold or distributed. The second cost is the annual fund operating expense, usually called the expense ratio, which covers the funds' expenses, the largest of which is for investment management. This charge is imposed annually. This cost occurs on all funds and for all types of distribution. We discuss each cost next.

Sales charges on mutual funds are related to their method of distribution. The current menu of sales charges and distribution mechanisms has evolved significantly and is now much more diverse than it was a decade ago. To understand the current diversity and the evolution of distribution mechanisms, consider initially the circumstances of a decade ago. At that time, there were two basic methods of distribution, two types of sales charges, and the type of the distribution was directly related to the type of sales charge.

The two types of distribution were sales-force and direct. Sales-force distribution occurred via an intermediary, that is via an agent, a stockbroker, insurance agent, or other entity who provided investment advice and incentive to the client, actively "made the sale," and provided subsequent service. This distribution approach is active, that is the fund is typically sold, not bought.

The other approach is direct (from the fund company to the investor), whereby there is no intermediary or sales-person to actively approach the client, provide investment advice and service, or make the sale. Rather, the client approaches the mutual fund company, most likely by a toll-free telephone number, in response to media advertisements or general information, and opens the account. Little or no investment counsel or service is provided either initially or subsequently. With respect to the mutual fund sale, this is a passive approach, although these mutual funds may be quite active in their advertising and other marketing activities. Funds provided by the direct approach are bought, not sold.

There is a quid pro quo, however, for the service provided in the sales-force distribution method. The quid pro quo is a sales charge borne by the customer and paid to the agent. The sales charge for the agent-distributed fund is called a load. The traditional type of load is called a front-end load, since the load is deducted initially or "up front." That is, the load is deducted from the amount invested by the client and paid to the agent/distributor. The remainder is the net amount invested in the fund in the client's name. For example, if the load on the mutual fund is 5% and the investor invests $100, the $5 load is paid to the agent and the remaining $95 is the net amount invested in the mutual fund at NAV. Importantly, only $95, not $100, is invested in the fund. The fund is, thus, said to be "purchased above NAV" (that is, the investor pays $100 for $95 of the fund). The $5 load compensates the sales agent for the investment advice and service provided to the client by the agent. The load to the client, of course, represents income to the agent.

Let's contrast this with directly placed mutual funds. There is no sales agent and, therefore, there is no need for a sales charge. Funds with no sales charges are called no-load mutual funds. In this case, if the client provides $100 to the mutual fund, $100 is invested in the fund in the client's name. This approach to buying the fund is called buying the fund "at NAV," that is, the whole amount provided by the investor is invested in the fund.

Previously, many observers speculated that load funds would become obsolete and no-load funds would dominate because of the sales charge. Increasingly financially sophisticated individuals, the reasoning went, would make their own investment decisions and not need to compensate agents for their advice and service. But the actual trend has been quite different.

Why has the trend not been away from the more costly agent distributed funds as many expected? There are two reasons. First, many investors have remained dependent on the investment counsel and service, and perhaps more importantly, the initiative of the sales agent. Second, sales-force distributed funds have shown considerable ingenuity and flexibility in imposing sales charges, which both compensate the distributors and are acceptable to the clients. Among the adaptations of the front end sales load are back-end loads and level loads. While the front-end load is imposed at the time of the purchase of the fund, the back-end load is imposed at the time fund shares are sold or redeemed. Level loads are imposed uniformly each year. These two alternative methods both provide ways to compensate the agent. However, unlike with the front-end load, both of these distribution mechanisms permit the client to buy a fund at NAV—that is, not have any of their initial investment debited as a sales charge before it is invested in their account.

The most common type of back-end load currently is the contingent deferred sales charge (CDSC). This approach imposes a gradually declining load on withdrawal. For example, a common "3,3,2,2,1,1,0" CDSC approach imposes a 3% load on the amount withdrawn within one year, 3% within the second year, 2% within the third year, and so on. There is no sales charge for withdrawals after the sixth year. Thus, the sales charge is postponed or deferred, and it is contingent upon how long the investment is held.

The third type of load is neither a front-end load at the time of investment nor a (gradually declining) back-end load at the time of withdrawal, but a constant load each year (e.g., a 1% load every year). This approach is called a level load. Most mutual fund families are strictly either no-load (direct) or load (sales-force).

Many load type mutual fund families often offer their funds with all three types of loads—that is, front-end loads (usually called "A shares"); back-end loads (often called "B shares"); and level loads (often called "C shares"). These families permit the distributor and its client to select the type of load they prefer. [See O'Neal (1999).] These different types of load shares are called share "classes." A recent type of share class is "F shares." F shares have no front, level or back loads. In this way they are like C shares. But F shares have considerably lower annual expenses than C shares, as will be seen below. F shares are designed for financial planners who charge annual fees (called fee-based financial planners) rather than sales charges such as commissions or loads. F shares of a fund family may only be sold by investment dealers and their representatives which have an arrangement with the fund family.

According to the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), the maximum allowable sales charge is 8.5%, although most funds impose lower charges.

The sales charge for a fund applies to most, even very small, investments (although there is typically a minimum initial investment). For large investments, however, the sales charge may be reduced. For example, a fund with a 4.5% front-end load may reduce this load to 3.0% for investments over $1 million. At some level of investment the front-end load will be 0%. There may be in addition further reductions in the sales charge at greater investments. The amount of investment needed to obtain a reduction in the sales charge is called a breakpoint—the breakpoint is $1 million in this example. There are also mechanisms whereby the total amount of the investment necessary to qualify for the breakpoint does not need to be invested up front, but only over time (according to a "letter of intent" signed by the investor). (See Inro, Jaing, Ho, and Lee, 1999.) Fund returns are calculated without subtracting sales charges since different individual investors have different sales charges (e.g., may have different breakpoints).

The sales charge is, in effect, paid by the client to the distributor. How does the fund family, typically called the sponsor or manufacturer of the fund, cover its costs and make a profit? This is the topic of the second type of "cost" to the investor, the fund annual operating expense.

The operating expense, also called the expense ratio, is debited annually from the investor's fund balance by the fund sponsor. The three main categories of annual operating expenses are the management fee, distribution fee, and other expenses.

The management fee, also called the investment advisory fee, is the fee charged by the investment adviser for managing a fund's portfolio. If the investment adviser is part of a company separate from the fund sponsor, some or all of this investment advisory fee is passed on to the investment adviser by the fund sponsor. In this case, the fund manager is called a subadviser. The management fee varies by the type of fund, specifically by the risk of the asset class of the fund. For example, the management fee as well as the risk may increase from money market funds to bond funds, to U.S. growth stock funds, to emerging market stock funds, as illustrated by examples to come.

In 1980, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) approved the imposition of a fixed annual fee, called the 12b-l fee, which is, in general, intended to cover distribution costs, also including continuing agent compensation and manufacturer marketing and advertising expenses. Such 12b-l fees are now imposed by many mutual funds. By law, 12b-l fees cannot exceed 1% of the fund's assets per year. The 12b-l fee may also include a service fee of up to 0.25% of assets per year to compensate sales professionals for providing services or maintaining shareholder accounts. The major rationale for the component of the 12b-l fee which accrues to the selling agent is to provide an incentive to selling agents to continue to service their accounts after having received a transaction-based fee such as a front-end load. As a result, a 12b-l fee of this type is consistent with sales-force sold, load funds, not with directly sold, no-load funds. The rationale for the component of the 12b-l fee which accrues to the manufacturer of the fund is to provide incentive and compensate for continuing advertising and marketing costs.

Other expenses include primarily the costs of (1) custody (holding the cash and securities of the fund), (2) the transfer agent (transferring cash and securities among buyers and sellers of securities and the fund distributions, etc.), (3) independent public accountant fees, and (4) directors' fees.

The sum of the annual management fee, the annual distribution fee, and other annual expenses is called the expense ratio or annual operating expense. All the cost information on a fund, including selling charges and annual expenses, are included in the fund prospectus. In addition to the annual operating expenses, the fund prospectus provides the fees which are imposed only at the time of a fund transaction.

As we explained earlier, many agent-distributed funds are provided in different forms, typically the following:

(1) A shares: front-end load; (2) B shares: back-end load (contingent deferred sales charge); (3) C shares: level load; and (4) F shares: fee based program. These different forms of the same fund are called share classes. Table 60.1 provides an example of hypothetical sales charges and annual expenses of funds of different classes for an agent distributed stock mutual fund. The sales charge accrues to the sales agent. The management fee accrues to the mutual fund manager. The 12b-l fee accrues to the sales agent and the fund sponsor. Other expenses, including custody and transfer fees and the fees of managing the fund company, accrue to the fund sponsor to cover expenses. All of these expenses are deducted from fund returns on an annual basis.

Share classes were first offered in 1989 following the SEC's approval of multiple share class. Initially share classes were used primarily by sales-force funds to offer alternatives to the front-end load as a means of compensating brokers. Later, some of these funds used additional share classes as a means of offering the same fund or portfolio through alternative distribution channels in which some fund expenses varied by channel. Offering new share classes was more efficient and less costly than setting up two separate funds. [See Reid (2000).] By the end of the 1990s, the average long-term sales-force fund offered nearly three share classes. Direct market funds tended to continue to offer only one share class.

There are several advantages of the indirect ownership of securities by investing in mutual funds. The first is risk reduction through diversification. By investing in a fund, an investor can obtain broad-based ownership of a sufficient number of securities to reduce portfolio risk. While an individual investor may be able to acquire a broad-based portfolio of securities, the degree of diversification will be limited by the amount available to invest. By investing in an investment company, however, the investor can effectively achieve the benefits of diversification at a lower cost even if the amount of money available to invest is not large.

The second advantage is the reduced cost of contracting and processing information because an investor purchases the services of a presumably skilled financial adviser at less cost than if the investor directly and individually negotiated with such an adviser. The advisory fee is lower because of the larger size of assets managed, as well as the reduced costs of searching for an investment manager and obtaining information about the securities. Also, the costs of transacting in the securities are reduced because a fund is better able to negotiate transactions costs; and custodial fees and record-keeping costs are less for a fund than for an individual investor. For these reasons, there are said to be economies of scale in investment management.

Table 60.1. Hypothetical Sales Charges and Annual Expenses of Funds of Different Classes for an Agent Distributed Stock Mutual Fund

Sales Charge | Annual Operating Expenses | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Front | Back | Level | Management Fee | Distribution (12b-1 Fee) | Other Expenses | Expense Ratio | |

a3%, 3%, 2%, 2%, 1%, 0%. | |||||||

A | 4.5% | 0 | 0% | 0.90% | 0.25% | 0.15% | 1.30% |

B | 0 | a | 0% | 0.90% | 1.00% | 0.15% | 2.05% |

C | 0 | 0 | 1% | 0.90% | 1.00% | 0.15% | 2.05% |

F | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.90% | 0.25% | 0.15% | 1.30% |

Third, and related to the first two advantages, is the advantage of the professional management of the mutual fund. Fourth is the advantage of liquidity. Mutual funds can be bought or liquidated any day at the closing NAV. Fifth is the advantage of the variety of funds available, in general, and even in one particular funds family, as discussed later.

Finally, money market funds and some other types of funds provide payment services by allowing investors to write checks drawn on the fund, although this facility may be limited in various ways.

Mutual funds have been provided to satisfy the various investment objectives of investors. In general, there are stock funds, bond funds, money market funds, and others. Within each of these categories, there are several sub-categories of funds. There are also U.S.-only funds, international funds (no U.S. securities), and global funds (both U.S. and international securities). There are also passive and active funds. Passive (or indexed) funds are designed to replicate an index, such as: the S&P 500 Stock Index; the Lehman Aggregate Bond Index; or the Morgan Stanley Capital International EAFE Index (Europe, Australasia, and the Far East). Active funds, on the other hand, attempt to outperform an index by actively trading the fund portfolio. There are also many other categories of funds, as discussed below. Each fund's objective is stated in its prospectus, as required by the SEC and the "1940 Act," as discussed below.

Stock funds differ by:

The average market capitalization ("market cap") (large, mid, and small) of the stocks in the portfolio.

Style (growth, value, and blend).

Sector—"sector funds" specialize in one particular sector or industry, such as technology, healthcare, or utilities.

With respect to style, stocks with high price-to-book value and price-to-earnings ratios are considered "growth stocks," and stocks with low price-to-book value and price-to-earnings ratios are considered value stocks, although other variables may also be considered. There are also blend stocks with respect to style.

Bond funds differ by the creditworthiness of the issuers of the bonds in the portfolio (e.g., U.S. government and investment-grade and high-yield corporates) and by the maturity (or duration) of the bonds (long, intermediate, and short.) There is also a category of bond funds called municipal bond funds whose interest income is exempt from federal income taxes. Municipal funds may be single state (that is, all the bonds in the portfolio were issued by issuers in the same state) or multistate or "national."

There are also other categories of funds such as asset allocation, hybrid, target date, and balanced funds (all of which hold both stocks and bonds), and convertible bond funds.

There is also a category of money market funds (maturities of one year or less) which provide protection against interest rate fluctuations. These funds may have some degree of credit risk (except for the U.S. government money market category). Many of these funds offer check-writing privileges. In addition to taxable money market funds, there are also tax-exempt municipal money market funds.

Among the other fund offerings are index funds and funds of funds. Index funds, as discussed above, attempt to passively replicate an index. Funds of funds invest in other mutual funds not in individual securities. A fund of funds is a fund that invests in other mutual funds.

Several organizations provide data on mutual funds. The most popular ones are Morningstar and Lipper. These firms provide data on fund expenses, portfolio managers, fund sizes, and fund holdings. But perhaps most importantly, they provide performance (that is, rate of return) data and rankings among funds based on performance and other factors. To compare fund performance on an "apples to apples" basis, these firms divide mutual funds into several categories which are intended to be fairly homogeneous by investment objective. The categories provided by Morningstar and Lipper are similar but not identical. Many of the categories of these two services are shown and compared in Table 60.2. Thus, the performance of one Morningstar "large-cap blend" fund can be meaningfully compared with another fund in the same category, but not with a "small-cap value" fund. Morningstar's performance ranking system whereby each fund is rated on the basis of return and risk from one star (the worst) to five stars (the best) relative to the other funds in its category is well known.

Mutual fund data are also provided by the Investment Company Institute, the national association for mutual funds.

A concept that revolutionized the fund industry and benefited many investors is what the mutual fund industry calls a family of funds, a group of funds or a complex of funds. That is, many fund management companies offer investors a choice of numerous funds with different investment objectives in the same fund family. In many cases, investors may move their assets from one fund to another within the family at little or no cost, and with only a phone call. Of course, if these funds are in a taxable account, there may be tax consequences to the sale. While the same policies regarding loads and other costs may apply to all the funds in a family, a management company may have different fee structures for transfers among different funds in its family.

Table 60.2. Fund Categories: Morningstar versus Lipper

Morningstar | Lipper | ||

|---|---|---|---|

LG | Large G rowth | LG | Large-Cap Growth |

LV | Large Value | LV | Large-Cap Value |

LB | Large Bland | LC | Larga-Cap Core |

MG | Mid-Cap Growth | MG | Mid-Cap Growth |

MG | Mid-Cap Value | MV | Mid-Cap Value |

MB | Mid-Cap Blend | MC | Mid-Cap Core |

SG | Small Growth | SG | Small-Cap Growth |

SV | Small Value | SV | Small-Cap Value |

SB | Small Blend | SC | Small-Cap Core |

XG | Multi-Tap Growth | ||

XV | Multi-Cap Value | ||

XC | Multi-Cap Core | ||

MA | Moderate Allocation | BL | Balanced |

CA | Conservationai Allocation | MP | Stock/Bond Blend |

TA | Target-Date 2004-2014 | ||

TB | Target-Date 2015-2029 | ||

TC | Target-Date 2030+ | ||

DH | Domestsc Hybrid | EI | Equity Income |

SP | S&P 500 Funds | ||

SQ | Specialty Diversified Equity | ||

ST | Technology | TK | Science & Technology |

SU | Utilities | UT | Utility |

SH | Health | HB | Health/Biotech |

SC | Communication | - | Telecommunications |

SF | Financial | - | |

SN | Natural Resources | NR | Natural Resources |

SP | Precious Metals | AU | Gold Oriented |

SR | Reai.Estate | - | Real Estate |

BM | Bear Market | - | |

LO | Long-Short | - | |

- | SQ | Special Equity | |

- | SE | Sector | |

FS | Foreign Stock | IL | International Stock (non-U.S.) |

WS | World Stock | GL | Global Stock (inc. U.S.) |

ES | Europe Stock | EU | European Region |

EM | Diversified Emerging Mkt. | EM | Emerging Markets |

DP | Diversified Pacific Asia | PR | Pacific Region |

PJ | Pacific ex-Japan | - | |

JS | Japan Stock | - | |

LS | Latin America Stock | LT | Latin American |

IH | International Hybrid | - | |

CS | Short-Term Bond–General | SB | Short-Term Bond |

GS | Short Government | SU | Short-Term U.S. Govt. |

CI | Interm.-Term Bond–General | IB | Intermediate Bond |

GI | Interm. Government | IG | Intermediate U.S. Govt. |

MT | Mortgage | MT | Mortgage |

CL | Long-Term Bond—General | AB | Long-Term Bond |

GL | Long Government | LU | Long-Term U.S. Govt. |

IP | Inflation-Protected Bond | - | |

GT | General U.S. Taxable | ||

CV | Convertibles | - | |

UB | Ultrashort Bond | - | |

HY | High-Yield Bond | HC | High-Yield Taxable |

MU | Multisector Bond | - | |

IB | World Bond | WB | World Bond |

EB | Emerging Market Bond | ||

BL | Bank Loan | ||

ML | Muni National Long | GM | General Muni Debt |

MI | Muni National Interm. | IM | Interm. Muni Debt |

MS | Muni National Short | SM | Short-Term Muni Debt |

HM | High Yield Muni | HM | High Yield Muni |

SL | Muni Single St. Long | NM | Insured Muni |

SI | Muni Single St. Interm. | SS | Single-State Muni |

SS | Muni Single St. Short | ||

MY | Muni New York Long | ||

MC | Muni California Long | ||

MN | Muni New York | ||

Interm./Sht | |||

MF | Muni California | ||

Interm./Sht | |||

Large fund families usually include money market funds, U.S. bond funds of several types, global stock and bond funds, broadly diversified U.S. stock funds, U.S. stock funds which specialize by market capitalization and style, and stock funds devoted to particular sectors such as healthcare, technology or gold companies. Well-known management companies, such as Vanguard, American Funds, and Fidelity the three largest fund families, sponsor and manage varied types of funds in a family. Fund families may also use external investment advisers (called subadvisors) along with their internal advisers in their fund families.

Fund data provided in newspapers group the various funds according to their families. For example, all the American Funds are listed under the American Fund heading, all the funds of Vanguard are listed under their name, and so on.

Mutual funds must distribute at least 90% of their net investment income earned (bond coupons and stock dividends) exclusive of realized capital gains or losses to shareholders (along with meeting other criteria) to be considered a regulated investment company (RIC) and, thus, not be required to pay taxes at the fund level prior to distributions to shareholders. Consequently, funds always make these distributions. Taxes, if this criterion is met, are then paid on distributions, only at the investor level, not the fund level. Even though many mutual fund investors choose to reinvest these distributions, the distributions are taxable to the investor, either as ordinary income or capital gains (long term or short term), whichever is relevant.

Capital gains distributions must occur annually, and typically occur late during the calendar year. The capital gains distributions may be either long-term or short-term capital gains, depending on whether the fund held the security for a year or more. Mutual fund investors have no control over the size of these distributions and, as a result, the timing and amount of the taxes paid on their fund holdings is largely out of their control. In particular, withdrawals by some investors may necessitate sales in the fund, which in turn cause realized capital gains and a tax liability to accrue to investors who maintain their holding.

New investors in the fund may assume a tax liability even though they have no gains. That is, all shareholders as of the date of record receive a full year's worth of dividends and capital gains distributions, even if they have owned shares for only one day. This lack of control over capital gains taxes is regarded as a major limitation of mutual funds. In fact, this adverse tax consequence is one of the reasons suggested for a closed-end company's price selling below par value. Also, this adverse tax consequence is one of the reasons for the popularity of exchange-traded funds to be discussed later.

Of course, the investor must also pay ordinary income taxes on distributions of income. Finally, when the fund investors sell the fund, they will have long-term or short-term capital gains, taxes, depending on whether they held the fund for a year or less.

There are four major laws or Acts which relate either indirectly or directly to mutual funds. The first is the Securities Act of 1933 ("the '33 Act") which provides purchasers of new issues of securities (the "primary market") with information regarding the issuer and, thus, helps prevent fraud. Because open-end investment companies issue new shares on a continuous basis, mutual funds must comply with the '33 Act. The Securities Act of 1934 ("the '34 Act") is concerned with the trading of securities once they have been issued (the "secondary market"), with the regulation of exchanges, and with the regulation of broker-dealers. Mutual fund portfolio managers must comply with the '34 Act in their transactions.

All investment companies with 100 or more shareholders must register with the SEC according to the Investment Company Act of 1940 ("the '40 Act"). The primary purposes of the '40 Act are to reduce investment company selling abuses and to ensure that investors receive sufficient and accurate information. Investment companies must provide periodic financial reports and disclose their investment policies to investors. The '40 Act prohibits changes in the nature of an investment company's fundamental investment policies without the approval of shareholders. This Act also provides some tax advantages for eligible RICs, as indicated below. The purchase and sale of mutual fund shares must meet the requirements of fair dealing that the SEC '40 Act and the NASD (National Association of Securities Dealers), a self-regulatory organization, have established for all securities transactions in the United States.

Finally, the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 specifies the registration requirements and practices of companies and individuals who provide investment advisory services. This Act deals with registered investment advisers (RIAs).

Overall, while an investment company must comply with all aspects of the '40 Act, it is also subject to the '33 Act, the '34 Act, and the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

The SEC also extended the '34 Act in 1988 to provide protections such that advertisements and claims by mutual funds would not be inaccurate or misleading to investors. New regulations aimed at potential self-dealing were established in the Insider Trading and Securities Fraud Enforcement Act of 1988, which requires mutual fund investment advisers to institute and enforce procedures that reduce the chances of insider trading.

An important feature of the '40 Act exempts any company that qualifies as a "regulated investment company" from taxation on its gains, either from income or capital appreciation, as indicated above. To qualify as an RIC, the fund must distribute to its shareholders 90% of its net income excluding realized capital gains each year. Furthermore, the fund must follow certain rules about the diversification and liquidity of its investments, and the degree of short-term trading and short-term capital gains.

Fees charged by mutual funds are also, as noted previously, subject to regulation. The foundation of this regulatory power is the government's de facto role as arbiter of costs of transactions regarding securities in general. For example, the SEC and the NASD have established rules as part of the overall guide to fair dealing with customers about the markups dealers can charge financial institutions on the sale of financial assets. The SEC set a limit of 8.5% on a fund's load but allows the fund to pass through certain expenses under the 12b-l rule, as indicated below. On July 1, 1993, the SEC amended the rule to set a maximum of 8.5% on the total of all fees, inclusive of front-end and back-end loads as well as expenses such as advertising.

Some funds charge a 12b-l fee, as authorized in the '40 Act and created in 1980. At the time mutual funds were losing money and the SEC allowed funds to charge the fees to pay for marketing and distribution expenses to increase fund assets. This was envisioned as a temporary measure. The 12b-l fee may be divided into two parts. The first component is a distribution fee, which can be used for fund marketing and distribution costs. The maximum distribution fee is 0.75% (of net assets per year). The second is a service fee (or trail commission), which is used to compensate the sales professionals for their ongoing services. The maximum service fee is 0.25%. Thus, the maximum 12b-l fee is 1%. While no-load funds can have 12b-l fees, the practice has been that in order to call itself a no-load fund, its 12b-l fee must be at most 0.25% (all of which would be a distribution fee). In general, the distribution fee component of the 12b-l fee is used to develop new customers while the service fee is used for servicing existing customers.

A rule called "prospectus simplification" or "Plain English Disclosure" was enacted on October 1, 1998 to improve the readability of the fund prospectus and other fund documents. According to the SEC, prospectuses and other documents were written by lawyers for other lawyers and not for the typical mutual fund investor. This initiative mandated that prospectuses and other document be written in "plain English" for individual investors. Efforts to simplify fund information continues.

Among the recent SEC priorities that have directly affected mutual funds are:

Reporting after-tax fund returns. This requires funds to display the pre-liquidation and post-liquidation impact of taxes on one, five, and ten year returns both in the fund's prospectus and in annual reports. Such reporting could increase the popularity of tax-managed funds (funds with a high tax efficiency).

More complete reporting of fees, including fees in dollars and cents terms as well as in percentage terms.

More accurate and consistent reporting of investment performance.

Requiring fund investment practices to be more consistent with the name of a fund to more accurately reflect their investment objectives. The SEC now requires that 80% of a fund's assets be invested in the type of security that its name implies (e.g., healthcare stocks).

Disclosing portfolio practices such as "window dressing" (buying or selling stocks at the end of a reporting period to include desired stocks or eliminate undesired stocks from the reports at the end of the period in order to improve the appeared composition of the portfolio), or "portfolio pumping" (buying shares of stocks already held at the end of a reporting period to improve performance during the period).

Among the current SEC priorities are the following:

Reviewing 12b-l fees. A common view is that 12b-l fees no longer solve their original intended function and so they should be altered or eliminated.

Considering soft dollars again. Soft dollars are the use of transaction charges to a dealer to pay for fund expenses. Among the considerations are what type of expense can be paid, for example securities research, computer systems or computers and other real assets.

A general SEC topic is disclosure. Disclosure would pertain to the transparency of fund charges and fees including sales charges on various share classes. Disclosure would also pertain to conflicts of interest which would include selling agreements between funds and distributors and other types of revenue sharing. Some perceive that money is being transferred among the participants in the provision of 401(k).

The SEC is trying to specify the relationship between the providers of transactions services, R/Rs (registered representatives) and investment advice, IARs (investment adviser representatives) and their conflicts and obligations. Specifying which providers have a suitability responsibility and which have a fiduciary responsibility is a current SEC concern.

A mutual fund organization is structured as follows:

A board of directors (also called the fund trustees), which represents the shareholders who are the owners of the mutual fund.

The mutual fund, which is an entity based on the Investment Company Act of 1940.

An investment adviser, which manages the fund's portfolios and is a registered investment adviser (RIA) according to the Investment Adviser's Act of 1940.

A distributor or broker/dealer, which is registered under the Securities Act of 1934.

Other service providers, both external to the fund (the independent public accountant, custodian, and transfer agent) and internal to the fund (marketing, legal, reporting, etc.).

The role of the board of directors is to represent the fund shareholders. The board is composed of both "interested" (or "inside") directors who are affiliated with the investment company (current or previous management) and "independent" (or "outside") directors who have no affiliation with the investment company. Currently, regulations require that more than half of the board be composed of independent directors and that the chairperson can be either an interested or independent director.

The mutual fund enters into a contract with an investment adviser to manage the fund's portfolios. The investment adviser can be an affiliate of a brokerage firm, an insurance company, a bank, an investment management firm, or an unrelated company.

The distributor, which may or may not be affiliated with the mutual fund or investment adviser, is a broker-dealer.

The role of the custodian is to hold the fund assets, segregating them from other accounts to protect the shareholders' interests. The transfer agent processes orders to buy and redeem fund shares, transfers the securities and cash, collects dividends and coupons, and makes distributions. The independent public accountant audits the fund's financial statements.

There have been several significant recent changes in the mutual fund industry in addition to those discussed earlier in this chapter. Next we discuss these changes.

As explained earlier in this chapter, at the beginning of the 1990s there were two primary distribution channels, direct sales to investors and sales through brokers. Since then, fund companies and fund distributors developed and expanded sales channels beyond the two traditional channels. By the end of the 1990s, fund companies' use of multiple distribution channels resulted in a blurring of the distinction between direct and sales-force funds that had characterized funds at the beginning of the decade.

Fund companies and distribution companies developed new outlets for selling mutual funds and expanded their traditional sales channels. The changes that occurred are evident in the rising share of sales through third parties and intermediaries. Significant market trends account for these changes. In particular, many funds that had previously marketed only directly turned increasingly toward third parties and intermediaries for distribution.

Like direct-market funds, funds that were traditionally sold through a sales force moved increasingly to non-traditional sources of sales such as employer-sponsored pension plans, banks and life insurance companies, and fee-based advisers during the 1990s.

Below we describe the various nontraditional distribution channels.

Supermarkets

The introduction of the first mutual fund supermarket in 1992 marked the beginning of a significant change in the distribution of direct market funds. Specifically, during 1992, Charles Schwab & Co. introduced its OneSource service. With this and other supermarket programs, the organizer of the supermarket offers no-load funds from a number of different mutual fund companies. These supermarkets allow investors to purchase funds from participating companies without investors having to contact each fund company. The organizer of the supermarket also provides the investor with consolidated recordkeeping and a simple account statement.

These services provide a non-transaction-fee (NTF) program to provide access to multiple fund families under one roof and to help service the back-office needs of financial advisers. Through this service, investors can access many mutual fund families through one source and buy all the funds with no transaction fee (that is, no load).

On the one hand, these services make a mutual fund family more accessible to many more investors. On the other hand, they break the direct link between the mutual fund and the investor. According to these services, the mutual fund company does not know the identity of its investors through the supermarkets; only the supermarket, which distributes the funds directly to the investor knows their identity. These supermarkets fit the needs of fee-based financial planners very well. For individual investors and planners as well, supermarkets may offer one-stop shopping including the current "best of the breed."

Wrap Programs

Wrap accounts are managed accounts, typically mutual funds "wrapped" in a service package. The service provided is often asset allocation counsel; that is, advice on the mix of managed funds. Thus, mutual fund wrap programs provide investors with advice and assistance for an asset-based fee rather than the traditional front-end load. Wrap products are currently offered by many fund and nonfund companies. Wrap accounts are not necessarily alternatives to mutual funds, but may be different ways to package the funds.

Traditional direct market funds as well as sales-force funds are marketed through this channel.

Fee-Based Financial Advisers

Fee-based financial advisers are independent financial planners who charge investors a fee, typically as a percentage of assets under management, or an hourly charge. In return, they provide investment advice to their clients by selecting portfolios of mutual funds, ETFs, and securities. While many planners recommend mutual funds to their clients, others recommend portfolios of planner-selected securities.

Variable Annuities

Variable annuities represent another distribution channel. Variable annuities are "mutual funds in an insurance wrapper." Among their insurance features are the tax deferral of investment earnings until they are withdrawn, and higher charges (including a mortality charge for an insurance feature provided). Variable annuities are sold through insurance agents and other distributors as well as directly through some fund companies.

Until recently, fund manufacturers distributed only their own funds; fund distributors distributed only one manufacturer's funds; and typically employer defined contribution plans, such as 401(k)s, offered funds from only one distributor. However, the investors' demands for choice and convenience, and also the distributors' need to appear independent and objective, have incented essentially all institutional users of funds and distribution organizations to offer funds from other fund families in addition to their own (that is, if they also manufacture their own funds). In addition, mutual fund supermarkets distribute funds of many fund families with considerable facility and low costs. Many fund families offer funds from other families. When a distributor or distribution system sells the investment products of many mutual fund families, it is referred to as "open architecture."

The balance of power between fund manufacturers and distributors currently significantly favors distribution. That is, in general there are more funds available than distributors to sell them. In the mutual fund business, "distribution is king."

While mutual funds have become very popular with individual investors during the 1980s and 1990s, they are often criticized for two reasons. First, mutual funds shares are priced at, and can be transacted only at, the end-of-the-day (closing) price. Specifically, transactions (that is, purchases and sales) cannot be made at intraday prices, but only at the end-of-the-day closing prices. The second issue relates to taxes and the investors' control over taxes. As noted earlier in this chapter, withdrawals by some fund shareholders may cause taxable realized capital gains for shareholders who maintain their positions and in some cases even if they have held them for a few days.

During 1993, a new investment vehicle which has many of the same features of mutual funds but responds to these two limitations was introduced. This investment vehicle, called exchange-traded funds (ETFs), consists of investment companies that are similar to mutual funds but trade like stocks on an exchange. ETFs are described in more detail in Chapter 61 of Volume I. While they are open-ended, ETFs are, in a sense, similar to closed-end funds which have very small premiums or discounts from their NAV.

Table 60.3. Mutual Funds versus Exchange-Traded Funds

Mutual Funds | ETFs | |

|---|---|---|

Variety | Wide choice, passive and active portfolios | Choices currently limited to passive indexes. |

Taxation | Subject to taxation on dividend and realized capital gains. | Subject to taxation on dividend and realized capital gains. |

May have gains/losses when other investors redeem funds. | No gains/losses when other investors redeem funds. | |

May have gains/losses when s tocks in index are changed. | May have gains/losses when s tocks in index are changed. | |

Valuation | NAV based on actual stock market prices. | Creations and redemptions at NAV. Secondary prices may be valued somewhat above or below NAV, but deviation typically small due to arbitrage. |

Pricing | End-of-Day | Continuous |

Expenses | Low for Index Funds | Low, and in some cases, even lower than for index mutual funds |

Transaction Cost | None for no-load funds; sales charge for load funds. | Commission or brokerage |

Management Fee | Depends on fund; index funds have a range of management fees. | Depends on fund; tends to be very low on many stock index funds |

ETFs have been based on U.S. and international stock and bond indexes and subindexes. In addition to broad stock indexes, ETFs are also based on style, sector, and industry-oriented indexes.

In an ETF, it is the investment adviser's responsibility to maintain the portfolio such that it replicates the index and the index's return accurately. Because supply and demand determine the secondary market price of these shares, the exchange price may deviate slightly from the value of the portfolio and, as a result, may provide some imprecision in pricing. The deviation will be small, however, because arbitrageurs can create or redeem large blocks of shares on any day at NAV, significantly limiting the deviations.

Along with being able to transact in ETFs at current prices throughout the day comes the flexibility to place limit orders, stop orders, orders to short sell and buy on margin, none of which can be done with open-end mutual funds.

The other major distinction between open-end mutual funds and ETFs relates to taxation. For both open-ended funds and ETFs, dividend income and capital gains realized when the funds or ETFs are transacted are taxable to the investor. However, in addition, when there are redemptions, open-end mutual funds may have to sell securities (if the cash position is not sufficient to fund the redemptions), thus causing a capital gain or loss for those who held their shares, while ETFs do not have to sell portfolio securities since redemptions are effected by an in-kind exchange of the ETF shares for a basket of the underlying portfolio securities—not a taxable event to the investors according to the IRS. Therefore, investors in ETFs are subject to significant capital gains taxes only when they sell their ETF shares (at a price above the original purchase price). However, ETFs do distribute cash dividends and may distribute a limited amount of realized capital gains and these distributions are taxable. Overall, with respect to taxes, ETFs, like index mutual funds, avoid realized capital gains and the taxation thereof due to their low portfolio turnover. But, unlike index mutual funds (or other funds for that matter), they do not cause potentially large capital gains tax liabilities which accrue to those investors who hold their positions in order to meet other shareholder redemptions due to the unique way in which they are redeemed.

The pros and cons of mutual funds and ETFs are summarized in Table 60.3. Table 60.4 considers the tax differences in more detail. Overall, the ETFs have the advantages of intraday pricing and tax management, and many, but not all, have lower expenses than their corresponding index mutual funds. However, since open-ended funds are "transacted" through the fund sponsor and ETFs are traded on an exchange, the commissions on each ETF trade may make them unattractive for a strategy that involves several small purchases, as for instance, would result from strategies such as dollar cost averaging or monthly payroll deductions. However, ETFs may provide a viable alternative to mutual funds for many other purposes.

Table 60.4. Taxes: Mutual Funds versus ETFs

Mutual Funds | ETFs | |

|---|---|---|

Holding/Maintaining | ||

1. Taxes on Dividend, Income, and Realized Capital Gains | Fully Taxable | Fully Taxable |

2. Turnover of Portfolio | Withdrawal by other investors may necessitate portfolio sales and realized capital gains for holder. | Withdrawal by others does not cause portfolio sales and, thus, no realized capital gains for holder. |

Disposition | ||

3. Withdrawal of Investment | Capital gains tax on difference between sales and purchase price. | Capital gains tax on difference between sales and purchase price. |

4. Overall | May realize some capital gains due to some portfolio turnover. | Will not realize significant capital gains due to very low portfolio turnover. |

Inro, D. C, Jaing, C. X., Ho, M. Y. and Lee, W. Y. (1999). Mutual fund performance: Does fund size matter? Financial Analysts Journal, May/June: 74-87.

O'Neal, E. S. (1999). Mutual fund share classes and broker incentives. Financial Analysts Journal, September/October: 76-87.

Reid, B. (2000). The 1990s: A decade of expansion and changes in the U.S. mutual fund industry. Perspectives: Investment Company Institute 6, 3: 1-20.