ANTONIO VILLARROYA, MD

Global Head of Rates Derivatives Strategy, Merrill Lynch

Abstract: The European Monetary Union and the introduction of the euro currency went a long way toward making the Eurozone government market the largest bond market in the world. What's more, this status is unlikely to be challenged in the coming years, with the new member countries of the European Union expected to join the single currency over time. Yet despite being integrated in many aspects, it should not be forgotten that the market comprises many issuers, with different credit ratings and issuing techniques, so is not completely homogeneous. These differences in credit status, together with the varying liquidity of their issues, their eligibility for the futures market and other micro factors, are the main drivers of intra-euro rate differentials.

Keywords: European Monetary Union (EMU), Pfandbrief, Maastricht, universal mobile telecommunications system (UMTS) licenses, French OAT, Italian BTP, German OBL, Spanish bonos, U.S. Treasuries, cheapest to deliver (CTD), swap spreads, strips, trading platforms, EuroMTS, tracking error, repo, primary dealers, syndication, Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), Euribor panel

Despite the appearance of many new fixed-income assets, the government bond market continues to be, by far, the largest market in the Eurozone. In this chapter, we analyze the recent trends in this market, its primary and secondary markets, and the key intra-country spread determinants.

The history of the government bond market in continental Europe is relatively short, as most of the countries in this region did not have a liquid government bond market until the early 1990s. Yet, after several years of steady growth, the key event for the European government market was the culmination of the European Monetary Union (EMU) in January 1999. Up to that moment, the excessive fragmentation of the different European bond markets and the embedded exchange-rate risk had prevented the emergence of a large government bond market in Europe. Before this consolidation process, the market could not be considered deep enough to compete with the U.S. Treasury market as the asset of choice for investors looking for a liquid "risk-free" asset. The start of the EMU, therefore, made a much deeper government market possible, widening significantly this market's investor base.

Helped by its strong growth in the late 1990s, the euro government market totals more than €3.5 trillion as of January 2008 and has become the world's largest government bond market, helped also by the retreat of the U.S. Treasury market in the late 1990s. In fact, the euro market is around 65% larger than the Treasury market, and its outstanding issuance is 50% bigger than that of Japanese government bonds, accounting for approximately 40% of the world's outstanding government bonds as of mid-2007. This percentage was only around 13% of the combined G4 market in 1990.

The euro market has not only become the largest government bond market in terms of size, but also in terms of number of issues, with nearly 270 liquid issues (over €1 billion outstanding and one-year € maturity), significantly more than the 130 issues in the Treasury market and nearly 10 times more than the 25 liquid issues trading in the U.K. gilt market.

This market's growth rate has been fairly steady since the beginning of the EMU, with 1998 and 1999 registering the largest increases. Yet the pace of growth has decreased since then because of the large windfalls from third-generation telephone (universal mobile telecommunications system [UMTS]) licenses in some euro countries and the limits imposed by the region's Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), registering just single-digit growth rates in the three years from 2000 through 2002. Furthermore, the low interest-rate and steep yield-curve environment have caused a shift in euro government supply toward the Treasury bill market at the expense of the bond market.

The beginning of the EMU also benefited the other euro-denominated fixed income markets, among them quasi-sovereigns, high-grade and high-yield credit bonds and asset-backed securities. Yet, although all these other markets experienced a massive increase in the post-EMU years, they are still quite small compared with the government sector and still very far from reaching the relative size they represent in the U.S. fixed income market. The government market continues to account for nearly 60% of all euro-denominated bonds outstanding, followed by the Pfandbrief market (around 7%) and the financial sector bond market, with 10%.

Just three countries (Germany, Italy, and France) make up over two-thirds of the total euro government market, increasing this percentage to nearly 90% of total outstanding bonds if the Spanish, Dutch, and Belgian markets are included. These relative weights have remained very stable since the enginning of EMU although it is worth noting how the relative weight of those countries that follow the SGP more strictly diminished compared with those whose deficits have remained closer to the 3% threshold. In general terms, the amounts issued by each country are very close to their respective market weights, with the total amount of fixed-rate bond supply around €470 billion annually in recent years.

It is also interesting to note how the average duration of the different euro government bond markets has been converging in the past few years, with the duration of the lower-rated countries increasing to almost match the stable or declining duration figures of the core euro countries. This process has taken the modified duration of the euro G8 markets to within a 0.4-year range, with a range of just around 0.25 years for the euro G4 countries.

Due to the large percentage of short-end supply and the time decay of the longer-dated issuance, the bulk of outstanding government debt is concentrated in short-end maturities, with one-third of total debt outstanding maturing in less than three years and two-thirds in less than eight years. The large decline in outstanding terms above 10 years' maturity is also significant, with less than 20% maturing beyond this point. In terms of maturity, the main recent event in the euro market has been the launch of ultra-long government bonds, with France, for instance, issuing a 50-year OAT in 2005. Helped by the flatness of the long end of the euro curve, these bonds have been issued to help European pension funds better hedge their long-dated liabilities. This practice of issuing long-dated nominal or real bonds is more common in the United Kingdom, a market where asset-liability matching issues are more extreme.

The two main developments in the primary euro government bond market since the inception of the EMU have been the decline in the relative amount of government sector supply within the Eurozone bond market and the increase in competence of the euro debt agencies.

The healthy economic growth and fiscal consolidation seen in the Eurozone in the late 1990s helped to reduce debt-to-GDP ratios in this period, despite an increase in gross terms. This decline was especially obvious in the Mediterranean countries, whose deficit- and debt-to-GDP ratios fell significantly in the second half of the 1990s under the constraints of the Maastricht Treaty criteria. Helped also by the sale of third-generation telephone licences (UMTS) in 2000, some of these countries had to undertake buyback programs and/or bond exchanges to be able to provide liquidity to their markets amid their declining funding needs.

Subsequently, the deceleration in growth in the early 2000s took some of these deficit and debt ratios higher, even causing some rating downgrades (Italy and Greece) and showing the pro-cyclical nature of these countries' funding needs in both absolute and relative terms. It also showed how, in general, within a monetary union, growth is good for a specific bond market—especially in a relatively small country—as its effect in terms of reducing funding needs more than offsets the possible rate increase caused by inflation expectations floating higher.

The decline in the amount of government bonds being issued in the late 1990s was partially offset by a sharp increase in corporate bond supply, especially within the high-grade spectrum. Yet, despite its significant growth, this market is still very far from the government market in terms of bonds outstanding.

The broadening of the investor base prompted by the start of the EMU brought about a significant increase in competition between the various Eurozone sovereign issuers, magnified by the single currency and the small difference in the credit risk components of these similarly rated countries. If, before EMU, the currency risk had helped these borrowers to ensure a quasi-monopoly situation in their own markets, with the appearance of the euro currency, all these treasuries had to compete for the same pool of funds. This increase in competition forced the euro debt agencies to improve their transparency, predictability, and relationship with market participants.

Another important factor bought about by the EMU was the standardization of the bond markets, thanks to the beneficial effect on government debt of the exchangeability of that debt, thus increasing foreign investors' preference for these markets. To compete with other non-euro government markets, having a market as homogeneous as possible among all the different euro issuers was second to none. Accordingly, the euro treasuries increased their coordination in terms of the basic characteristics of their instruments, procedures, coupon calculation conventions (actual/actual), and even taxation. This subject has been studied by the Giovannini group for the European Commission, which produced several reports between 1997 and 2000 on the integration of the national treasuries and markets, giving some guidelines for better coordination of debt agencies with a view to achieving a better substitutability of bonds and a more efficient bond market.

The broadening of fixed income managers' mandates since the introduction of the single currency, the disappearance of foreign exchange risk for many investors, the redemption of long-held bonds, and the increase in exchangeability between these markets helped to increase significantly the percentage of sovereign debt held by nonresidents. As an example of a middle-sized market, the percentage of nonresident holdings of Spanish bonos increased from 20% before the EMU to well above 50% just four years later.

Another area on which the debt agencies had to increase their focus was their communications policy, as another of the obvious consequences of the above-mentioned loss of the domestic edge was the necessary increase in transparency and predictability, especially in terms of issuance policy. In fact, most euro debt agencies now publish periodical supply calendars, providing as much detail as possible on amounts and maturities to be issued, as well as any other useful information on new bond lines, swap operations, average duration targets, and the like. This information is shared with their respective market makers, and also via periodical bulletins and their web sites or pages on financial news services, such as Bloomberg or Reuters.

Besides this improvement in information provided to the market, the above-mentioned increase in competition has made the euro debt agencies improve as much as possible the liquidity of their bonds. Liquidity and credit ratings are the key drivers of the relative performance of euro countries' bonds and, therefore, the debt agencies will try to improve their bonds' liquidity to decrease their funding costs. In the primary market, this increase in liquidity has been key, as explained below.

The broadening of the investor base, together with the desire to enhance liquidity in the secondary market, has been the main driver of the continuous increase in not only the size of bond issuance outstanding, but also the amounts offered at each auction.

This has been more obvious in the largest euro countries, the clearest example being the euro benchmark government bond, the 10-year Bund. In fact, those German 10-year bonds issued in 1998-1999 had an average outstanding value of around €10 billion, but their size increased with the arrival of the euro to reach as much as €27 billion outstanding by 2002, stabilizing thereafter at around €25 billion. In addition, most Italian BTPs now reach outstanding amounts of more than €20 billion, while the average size of a French OAT is between €15 billion and €20 billion. Accordingly, these outstanding euro government bonds have become much closer to their U.S. counterparts, as some Treasuries reach the $35 billion level.

Although less extreme, a similar pattern has been observed, not only in other maturities of the German curve (current five-year OBLs total €20 billion, whereas the pre-EMU ones were between €5 billion and €8 billion), but also in practically all other euro countries. This increase in auctioned and outstanding sizes has been even more dramatic in the smaller countries.

The smaller euro countries, because of their smaller nominal funding needs, used to issue a large number of small bonds before the currency union. Yet the outstanding size of many of the bonds (many of them below €2 billion) did not reach sufficient levels to be considered a liquid asset in which investors could trade large amounts without significantly affecting its price. Therefore, these countries have had to concentrate most of their supply into just a few bonds a year, sometimes having to carry out exchange auctions or buybacks to reach this critical mass. This situation was even more extreme in the high-growth late 1990s period and in the fiscally stricter countries. Nowadays, practically only the euro G4 countries and Greece issue bonds across the entire yield curve, while the rest of the euro countries just launch a couple of bonds every year, tapping them afterwards to reach a minimum amount.

The level that could be considered a minimum for liquidity purposes could be the €5 billion MTS threshold. Below this level, bonds are considered too easy to squeeze and, therefore, their liquidity is much lower, creating a sort of vicious circle. This €5 billion level is actually the target many smaller euro countries have when they launch a new bond, especially when they are issued via syndicate. Otherwise, they tend to try to reach this amount as quickly as possible.

To reach this minimum amount as soon as possible, to reduce the level of their liabilities, smooth their debt's redemption profile, or improve the liquidity of selected issues, many European debt agencies carry out bond exchange auctions and/or buybacks. These operations are even more important for those countries that, due to their small size or strict fiscal policy, have low funding needs.

Bond Exchanges

The bond exchange procedure has been used profusely by many euro debt agencies, such as Spain, France, Italy, Portugal, and Belgium, which have been carrying out frequent bond exchange auctions for many years, either as one-off operations or by opening exchange windows during a specific period of time. As mentioned above, the main target of these exchanges is to provide liquidity to the new bonds as quickly as possible.

These operations have normally been concentrated in the last months of the year, as in a declining rate environment, exchanging old (that is, high-coupon) bonds for new, lower-coupon bonds has a cost because of the difference in price. Accordingly, these debt agencies tend to wait to have as much information as possible on the evolution of their countries' fiscal deficits in order to evaluate the amount of cash they can allocate to these operations. In general terms, these operations are well perceived by the market, as they allow investors to exchange their old, less liquid bonds for the new benchmarks. On top of this, the debt agency can increase the liquidity of its new benchmarks more rapidly than it otherwise could.

Bond Buybacks

The rationale behind bond buybacks is very similar to that behind the exchange auctions (that is, to increase the country's funding needs to allow larger—and faster—issuance of the current benchmark bonds). In fact, a buyback is just the first leg of an exchange auction, the other being the actual bond issuance. The main difference is that buybacks tend to be concentrated in short maturity bonds, thus helping to smooth the redemption profile by limiting upcoming years' redemption payments and, therefore, supply. The procedure for these buybacks could either be via OTC purchases or preannounced buyback windows, normally restricted to primary dealers.

Other key features of the primary markets include (1) issuance maturities and techniques, (2) issuing procedure, and (3) primary dealers. Each characteristic is discussed below.

Issuance Maturities and Type of Bonds

Although the introduction of the euro helped to homogenize some characteristics and maturities of the bonds issued, there are still some differences between the euro countries' supplied assets. Euro-denominated fixed-coupon bonds make up the bulk of issuance, but there are also some other types of bond issued by the Eurozone countries.

In general terms, the maturities issued are split between the short-end (two- and three-year), the intermediate sector (five-year), the long-end (10-year), and ultra-long-end bonds. Within this sector, the most frequently tapped maturity used to be the 30-year sector, although some countries also tap their 15-year bonds. In addition, since 2005, some euro countries have started to issue 50-year bonds, because of the low rate environment, the flatness of the long end of the curve—and therefore the low level of the forwards—and the increase in long-dated demand by pension funds and insurance companies, trying to improve the asset-liability match of their portfolios in an increasingly more regulated environment.

Most of these bonds normally pay fixed-rate coupons, the main exception being Italian CCTs, which have a seven-year maturity and pay a floating coupon related to the yield of the Italian six-month Treasury bills. Floating-rate note supply has fallen significantly since 1998-1999, although some countries still issue a small part of their supply in floating-rate notes. Another noticeable exception to fixed-coupon issuance is French TECs. These bonds' coupons, paid on a quarterly basis, are linked to the TeclO index, an average yield of OATs with a constant maturity of 10 years. Yet their supply has also decreased significantly over the last few years.

Finally, one sector that continues to gain importance, not only in terms of amounts issued, but also investor interest, is the inflation-linked bond market. Since 2004, Germany, Greece, and Italy have joined France in issuing this type of asset. The sector continues to gain relevance, and its outstanding issuance is already above €130 billion in France, over 15% of total French debt outstanding.

Issuing Procedure: Syndication versus Auctions

Because of some Eurozone countries' relatively low funding needs and due to the increase in competition for investor preference (and to achieve the above-mentioned critical mass), many countries are increasingly launching their new bonds via syndication. This method, used by most national treasuries and debt agencies, allows them to allocate large sums in one go (€5 billion is the usual amount) and reach a broader base of final investors, facilitating the good performance of the bonds after launch. These syndicate issues, also used by quasi-sovereign issuers, such as the EIB, Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (FHLMC), or Kreditanstalt Für Wiederaufbau (KfW), tend to be followed by subsequent taps.

In these syndicate issues, the borrower tends to name several (three to four) lead managers who would allocate most of the expected amount to be issued, with a co-lead group allocating the rest of this target amount. The lead group would, in normal terms, be formed by domestic and foreign banks, usually primary dealers in that market.

Primary Dealers

To ensure the good performance of their bond auctions and regular pricing of their bonds, the government debt agencies establish a group of primary dealers for their bond markets. In general terms, these institutions (normally investment banks) will have to bid in the auctions and quote a certain number of bonds with a maximum predetermined bid-offer spread. However, these banks have access to the second round of the auctions (under better conditions) and should be the main beneficiaries of other deals in these Treasuries, such as swap operations or the above-mentioned syndicate issuance.

In general terms, within a Monetary Union, the spreads between same maturity bonds from different countries should be determined by the relative liquidity of these bonds and their credit status.

With this in mind, yield differences among Eurozone countries should tend to diminish and almost disappear in the long run. On the one hand, the decline in these countries' financing needs as they strengthen their fiscal positions, forced by the SGP, tends to make their credit ratings converge, albeit slowly. On the other hand, the smaller countries, helped by a broader investor base within the single currency and the above-mentioned enhanced supply mechanisms and trading platforms, should see improved liquidity of their bonds, helping to diminish the liquidity component of their spreads to the core euro countries. This reduction in the liquidity premium and the relative creditworthiness of the Eurozone countries should make bond spreads converge in the long run.

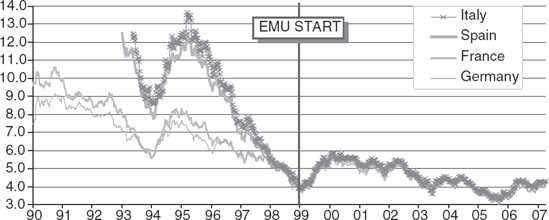

Yet it should be taken into account that a large part of this convergence had already taken place before the actual start of the EMU (see Figure 25.1). Once the market had priced in a significant probability of a country qualifying for entry into the euro, investors could put on convergence trades, tightening significantly the peripheral spreads to the euro core countries. These trades had a limited risk, as in most cases the final exchange rate parities were already known (mid-rate of the previous exchange rate mechanism, or ERM, bands).

Credit-rating agencies (CRAs) try to encapsulate in the qualifications they assign to different sovereign issuers the financial and economic conditions of a specific country, as well as its ability and willingness to pay its obligations. These ratings should, therefore, theoretically, be a good indicator of the financial health of the issuer and should be correlated to the yields and spreads within the Eurozone, as they should measure, to a certain extent, the borrowers' small but positive default probabilities.

It is also worth remembering that although the euro is their domestic currency, euro countries do not have the ability to unilaterally print money anymore and, therefore, the ratings these countries were assigned at the beginning of currency union equal their former foreign currency ratings as opposed to their domestic currency ones, which were better because of their ability to print their own money.

Before January 1999, four of the countries in the euro area already deserved the highest credit rating, according to the major three CRAs (Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Austria). From the start of currency union, three more countries have joined the top-notch club, namely Ireland (October 2001, S&P), Finland (February 2002, S&P), and Spain (December 2004, S&P). The rest of the countries are still below this category, with Greece being the lowest-rated country in the region (in the EMU since 2001). As seen in Table 25.1, there are no significant divergences between the ratings these three agencies assign to each specific country, although S&P and Fitch appear to be slightly stricter than Moody's in this regard.

Figure 25.1. German, French, Spanish, and Italian 10-Year Rates Converged at the Beginning of the EMU. Source: Created from data obtained from Bloomberg.

Table 25.1. Euro Countries' Credit Rating (December 2007)

Moody's | S&P | Fitch | Last change (Post EMU) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Germany | Aaa | AAA | AAA | ||

France | Aaa | AAA | AAA | ||

Netherlands | Aaa | AAA | AAA | ||

Austria | Aaa | AAA | AAA | ||

Ireland | Aaa | AAA | AAA | Oct-01 | Upgrade |

Finland | Aaa | AAA | AAA | Feb-02 | Upgrade |

Spain | Aaa | AAA | AAA | Dec-04 | Upgrade |

Belgium | Aa1 | AA+ | AA+ | ||

Portugal | Aa2 | AA- | AA | Jun-05 | Downgrade |

Italy | Aa2 | A+ | AA- | Oct-06 | Downgrade |

Greece | A1 | A | A | Nov-04 | Downgrade |

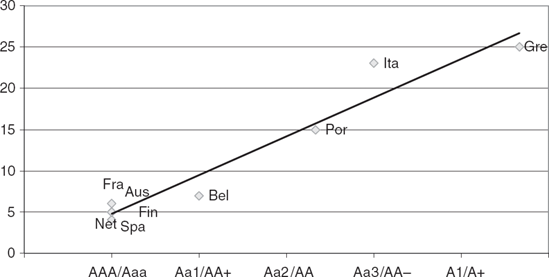

As these ratings reflect the ability and willingness of the countries to assume their obligations and, taking it to the extreme, their probability to default, there should be a direct relationship between the countries' ratings and their yields (or spreads to benchmark curve). This relationship is clearly shown in Figure 25.2, which represents each country's rating versus its average 10-year yield spread versus Germany in the five first years of currency union. It seems clear from the exhibit that there is an almost linear relationship between spreads and ratings, with the distance between each country's spread to the regression line being a proxy of each country's liquidity premium.

This "liquidity premium" is more evident in the AAA-rated category, where the market clearly differentiated between very liquid and deep markets, such as France, and smaller, less liquid countries, such as Austria. That said, most AAA-rated euro countries now trade very closely to each other, with their spreads normally within 5 basis points of each other for the same maturity.

Changes in the rating of any of these euro countries should, in theory, make its bonds under or outperform the rest of the markets, as was the case when Moody's upgraded the Kingdom of Spain by two notches to Aaa in December 2001. Yet, most of the time, these rating changes have been largely anticipated by the market, either due to the improvement in that country's official rating outlook or just based on previous comments or reports from these agencies. In fact, some well anticipated downgrades, such as the Italian one in July 2004, hardly had any market impact, as investors had been wary of holding large amounts of Italian BTPs prior to the well touted downgrade, and the actual cut to AA–was seen as an all-clear sign for investors who were underweight Italian debt in their portfolios to add some extra yield.

Credit ratings and the size and liquidity of each bond market are the main long-term drivers of intra-euro government bond spreads. Yet there are many other smaller and more micro spread drivers that are becoming increasingly more relevant, thanks to the above-mentioned credit and liquidity convergence among these countries.

Supply Dynamics, Fiscal Trends, and Issuance Policy

Although credit rating and fiscal outlook are by far the two most important spread drivers in the Eurozone, the extent of the market impact of these fiscal features depends significantly on the assets chosen to fund those needs. Fiscal needs have a noticeable impact on bond markets when these gaps are funded using government bonds, while their market impact is much more limited if this funding is obtained from other sources, such as Treasury bills, loans, privatizations, and so on. Another factor to bear in mind is that these issued amounts are relevant not only in gross, but also in net terms (ex-redemptions) as it is this second amount that better reflects each country's financial needs. In addition, it can be assumed that a sizeable part of the bonds being paid down (or bought back) are reinvested in the same market so as to keep unchanged the country composition of the portfolio, helping this market to outperform the rest of its euro counterparts, with a similar effect taking place for coupon payments.

Figure 25.2. 10-Year Spread to Germany (Average in the First Five Years of EMU) versus Credit Rating. Source: Data obtained from Merrill Lynch and BBG.

The breakdown of these countries' funding by maturity and type of asset is also affected by market dynamics, as, for instance, steep yield curves favor the increase in Treasury bill issuance (2000-2001), while low-rate and flat yield-curve environments make long-end issuance more interesting, locking in low funding levels for long periods.

The maturity breakdown of government bond issuance can also be key in determining euro government spreads. Accordingly, the announcement of an unexpected supply increase (or decrease) in a specific maturity can significantly affect the spreads and slope of the euro curve. This feature was clearly seen at the end of 2001, when the German debt agency announced its intention to issue just €6 billion in 30-year Bunds in 2002, considerably below market expectations. The initial reaction was not only clear outperformance of the German long end, but also sizeable flattening in the 30-/10-year slope and a widening of long German swap spreads. These dynamics underline the importance of accurate forecasting of the amounts and maturity breakdown of each country's upcoming supply. On top of this, when a bond auction takes place, the actual increase in the amount of paper in the market may affect its price simply due to supply-demand conditions, although such an impact can depend on the market conditions of that moment.

Bond Index Tracking and Passive Fund Management

As in many other financial markets, many fixed income fund managers measure their performance against bond indices, made up of the most liquid bonds in each market. So, any noticeable deviation in the characteristics of the managed portfolio from the index tracked means a risk for the asset manager. Therefore, these indexed funds tend to track (although to a different degree, depending on the risk characteristics of the portfolio) the evolution of the indices. In fact, the most passive funds managers try to minimize their tracking error by replicating dynamically the characteristics of the index in terms of average duration and country breakdown.

Accordingly, index-tracking fund managers have to anticipate any possible change in these indices to avoid increases in their tracking errors. The indices are usually rebalanced at the end of each month according to the bonds entering or leaving the index, with those months with heavy long-term supply and/or large drops from the index producing significant changes in index duration at month end. Indexed investors, therefore, have to buy or sell bonds around those days to match these duration changes. To minimize tracking error further, these managers have to make their adjustments at the same time as the index is rebalanced, with the obvious consequences for the bond market around that period.

Bond Future Deliverability

Bond futures have become, due to their liquidity and leverage characteristics, the main hedging and investment instruments of many market participants. Their open interest and traded volumes have, therefore, increased sharply in the last few years. As the underlying issues of these futures are specific government bonds, these bonds tend to follow a similar evolution to the future they represent. Accordingly, the bonds included in an exchange-traded future deliverable basket and, especially, the cheapest to deliver (CTD) tend to trade rich in their own curve, thanks to the large amount of long and short positions in the future, as well as the possibility of squeezes in the delivery dates.

The degree of its dearness will depend, among other factors, on the outstanding amount of the bond, the open interest of the future, bond-market volatility and the bond's supply dynamics. As discussed next, Eurex's victory in the Eurozone "battle of the futures" has made German deliverable (and CTD) bonds trade richer than other German and euro bonds in their respective maturities.

The evolution of euro government bond peripheral spreads has always been linked to the performance of swap spreads (and vice versa). Yet this relationship should be taken with a pinch of salt, as, with the German rate on both sides of the equation, any spike in the German Bund market will make this correlation increase spuriously.

That said, there are two reasons why the performance of German swap spreads are related to euro peripheral spreads. The first is that, flows apart, the bond-swap spread reflects the yield differential between a government rate and the composition of a string of Euribor rates (that is, a swap fixed rate). As the average credit quality of the banks in the Euribor panel is A to AA, any increase in investor preference for credit quality will make both swap and peripheral spreads widen versus the core euro government rate, thus increasing the correlation between both differentials. Yet, this increase in the correlation is mainly due to the outperformance of the benchmark asset (German bonds in this case) rather than to any similarity between the swap rate and that of the peripheral country.

One recent driver of peripheral versus core spreads has been the sharp decline in financial-market volatility in 2004 through 2007, mainly as a result of abundant global liquidity, as well as the increasing efficiency and transparency of central banks. In this low-volatility environment, the search for any yield pickup becomes crucial, and the extra yield offered by the high-yielding countries becomes even more interesting. Taking it to the extreme, in a world where spread volatility disappears, the yield pickup offered by the peripheral countries becomes a free lunch for investors—even more considering that all euro countries enjoy the same status in terms of eligibility for repo operations with the European Central Bank. Accordingly, any model trying to forecast, for instance, German-Italian yield spreads—based, for example, on Bund swap spreads—would need to incorporate the decline in rate volatility to justify the decline in these differentials.

Government bond markets are closely related to other fixed income assets and interest rate and bond futures. This market is also increasingly related to the interest rate swap market.

Wholesale Electronic Markets and Trading Platforms

One of the most significant developments since the start of the euro has been the success of EuroMTS, an electronic broking system launched in April 1999. Before 1999, most bond markets were telephone based, but this platform has expanded rapidly to cover practically all the government markets and its market share has expanded significantly. The success of these trading platforms has been favored by the broadening of this market with the start of the currency union and they have become very important in increasing investor confidence, market liquidity, and price transparency. This increase in platform trading has not only taken place in the Eurozone, being has also been the case in the United States and other bond markets.

The other advance in bond trading has been dealer-to-customer platforms, where institutions can compare prices from several intermediaries simultaneously, with the obvious benefit for final investors.

Strip Markets

Many euro government bonds can be stripped, breaking them down into the single payments they involve, that is, one flow for each remaining coupon payment and another for the principal. With this procedure, an n-year maturity coupon-bearing bond is transformed into n + 1 strips (zero-coupon bonds), which can be traded separately in the market. Yet this market is much less liquid in the Eurozone than in the United States.

Repo Markets

Despite the homogenization of euro government bond markets, repo markets have remained largely domestic and unevenly developed throughout the single-currency area, showing hardly any increase in cross-border transactions. Regulatory, legal, and tax-specific issues, as well as different market practices, have been the main reason for the lack of a truly unified repo market in the euro area.

Euro Futures and Options Market

The large increase in the size and number of investors in the euro government bond market has brought about a significant improvement in the depth and liquidity of the bond futures market. In fact, since 1999, Eurex has continued to confirm its status as the most active derivatives exchange globally, ahead of the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), while the Bund contract has established itself firmly as the most actively traded futures contract in the world. This 10-year bond-based future is actually the most widely used hedging instrument for all euro-denominated issues.

In this regard, the winner-takes-all characteristic of a futures market (where liquidity is key) sparked a dispute between the Eurex and Matif futures exchanges in the initial years of the monetary union. While their characteristics were very similar (it could even be argued that Matif's future coupon was closer to existing bond yields), the winner of this battle appears to have been the Eurex future, becoming the main reference for all maturities (10-year Bunds, five-year Bobl, two-year Schatz, and even the 30-year Buxl). These contracts include only German bonds in the deliverable baskets, helping to keep this country's deliverable bonds more expensive than the other euro countries, helped also by the existence of an options market linked to these futures.

Given the absence of a single, clearly defined benchmark sovereign yield curve and the continuous expansion of the interest rate swap market since the late 1990s, government bond market participants have increased the use of the swap curve as a reference for the valuation (and hedge) of government and nonsovereign bonds. Another factor that has enhanced the depth and liquidity of the swap market is the enlargement of the Eurozone corporate bond market, as both investors and issuers can use swaps to convert their fixed-rate liabilities into floating-rate ones, or vice versa.

It has, in fact, been argued that interest-rate swaps could eventually replace government bonds in many of their functions, such as extracting information on the future path of short-term rates, or hedging interest-rate risks, their also being a more homogeneous asset. Yet it should not be forgotten that government bonds will remain the key funding vehicle for these sovereign issuers and that their significantly lower credit risk makes these assets a cleaner tool for assessing future rate changes and hedging interest rate risks, while they are the perfect candidate for performing the function of collateral.

In this chapter, we first analyzed the substantial growth in the Eurozone government bond market and the changes brought about by the European Monetary Union. We then focused on the main drivers of interest rate differentials between these countries, namely, credit and liquidity, as well as financial market volatility. Finally, we focused on integration and the continued differences between the region's issuers, as well as related markets: strips, futures, repos, and swaps.

European Commission, Maastricht criteria. (1992). European Community Treaty, Article 121 (1), February.

Bank of Spain. (2001). The euro-area government securities markets. Bank of Spain working paper 0120, October.

Giovannini Group. (2000). Report on co-ordinated issuance of public debt in the euro area, November.

Bank for International Settlements. (2006). Triennial Central Bank survey of foreign exchange and derivatives market activity, September.

Standard & Poor's. (2006). Ratings definitions, December, update.