MAHMOUD A. EL-GAMAL, PhD

Professor of Economics and Statistics, and Chair of Islamic Economics, Finance, and Management at Rice University

Abstract: Islamic finance began to take shape in the 1970s. It was fueled financially by the flow of petrodollars to Islamic countries in the oil-rich Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, and fueled ideologically by the nationalist and Islamist movements that took shape during the first half of the twentieth century. This industry has witnessed dramatic growth over the past decade, fueled again by petrodollar flows and resurgence of nationalist and Islamist tendencies. As will become apparent shortly, the demarcation between Islamic and conventional financial practices is almost exclusively a matter of contract form. This makes Islamic finance a branch of structured finance more generally. A third reason for growth in Islamic finance must thus be added to excess liquidity in the GCC and the rise in Islamist and nationalist sentiments, and that is the ready availability of structured-finance methods that were developed during the 1980s and 1990s.

Keywords: Islamic finance, structured finance, riba, gharar, bay` al-`ina, murabaha, salam, takaful, Fiqh, fatawa, tawarruq, securitization, da` wa ta`ajjal, ijara, sukuk al-ijara, sukuk, musharaka, mudaraba, salam, istisna`, `urbun

The purpose of this chapter is to describe Islamic finance briefly. This chapter is not written from the point of view of pious Muslims, or from a rigorous academic perspective. (For discussions of Islamic finance from the former perspective, see El-Gamal [2000]; from the latter perspective, see El-Gamal [2006].) Rather, this chapter is intended for financial practitioners seeking a basic understanding and critical evaluation of the modes of operation in Islamic finance. In my criticism of the industry's modes of operation, I argue that they are costly and unnecessary (that is, inefficient) forms of legal arbitrage.

While Islamic finance is a form of structured finance, there are two distinctive features that distinguish it from other forms of structured finance. The first difference pertains to regulatory constraints. Conventional structured finance aims to improve marketability and reduce costs and tax burdens by adhering to well-defined sets of regulations in various geographical regions. There has been no shortage in the 1980s and 1990s of attempts to standardize the set of regulations that determine whether or not a financial product or service may be marketed as Islamic. However, despite efforts by the Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) and the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), housed in Manama, Bahrain, and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, respectively, there remains a great deal of heterogeneity in what is deemed Islamic. Providers of Islamic financial products and services and their advisers, therefore, rely on the direct advice of religious scholars who have attained a reputation in Islamic finance.

This is particularly important for new and innovative products, the structure of which is often kept secret to prevent imitation by competitors. One of the major problems in this regard is that different religious scholars may be brought to court to testify against the Islamic nature of products and services approved by other scholars. This has happened, in fact, twice, before English courts. Fortunately for the Islamic financial providers in both cases, English courts decided to disregard Islamic law provisions and to award them the accrued interest, following English law. However, the issue of adherence to multiple legal systems, one of which is not clearly defined, remains a problem for this industry.

The second distinctive feature is that Islamic financial innovation generally tracks innovation in the conventional sector, with potentially substantial lags. On the supply side, providers of Islamic finance have traditionally approached the Islamic market with products that they had already been offering to conventional customers. Conversely, if demand for a new product is presented to conventional financial providers, the cheapest-to-deliver products can normally be found by restructuring conventional products that are already available. The legal and consulting fees required to restructure a conventional product or practice Islamically (e.g., commodity funds, mortgage-backed securities, leveraged buyouts, etc.) can be substantial. However, the lag in bringing those products and services to market are reduced significantly by focusing the discussions of bankers, lawyers, and religious scholars on providing the closest analog to well-defined products and services at minimal added transaction costs.

One of the most intimidating factors for newcomers to Islamic finance is the general use of religious rhetoric and excessive usage of Arabic words. Due to those tendencies, senior administrators at a major University in the United States that had established a program on Islamic finance in the 1990s were disturbed by what they characterized as ecumenical discourse. Many non-Muslim financial professionals also felt apprehensive at first, but then quickly learned to see through the seemingly ecumenical rhetoric. Part of the apprehension, no doubt, was driven by fear of offending the religious-scholar consultants who are needed to certify products and services as Islamic. However much religious rhetoric may tilt the initial power structure in favor of those scholars, the bankers and lawyers ultimately recognize that they control the process.

Three forces give conventional financial and legal professionals this power over the religious scholars: They get to choose whom to hire and publicize as an expert, they get to choose what questions should be asked of the hired scholars, and they get to choose which of the scholars' answers to disseminate. Once this simple first-mover advantage is understood, the next step for a financial professional is to learn how to cut through the religious rhetoric. This barrier to entry is not nearly as difficult as it may appear at first. The number of Arabic words to learn is quite small, and the concepts themselves constitute a rather primitive subset of conventional financial practices. This primer is intended for a financial professional, on the financial or legal side, and it should give them a good first understanding of the bulk of Islamic finance in less than half an hour.

It is generally accepted in Islamic jurisprudence that all contracts conducted by mutual consent are permissible, unless they contain one of two major prohibitions, known in Arabic as riba and gharar. There are other prohibitions, of course, that pertain to asymmetry of bargaining power, such as would be the case in monopolistic markets. However, the focus in Islamic finance has been fundamentally focused on contract forms, rather than economic substance or market structure. Therefore, a newcomer to Islamic finance needs only to learn about those two prohibitions. Even then, only the most basic understanding of the general concepts is required, since practitioners often aim to avoid the prohibitions simply by using building-block contracts that have been previously approved, as we shall discuss in the following section.

The prohibition of riba predates Islam, as Islamic scriptures themselves report in discussion of Judeo-Christian prohibitions of ribit, a Hebrew word that obviously shares the same etymological root as its cousin Semitic Arabic word. Like the prohibition of usury in Judeo-Christian history, the prohibition of riba has been the subject of numerous scholastic disputes over the centuries. Since this primer is for financial professionals, those scholastic debates are largely irrelevant. The rhetoric used by industry practitioners and their pietist customers is quite simple. The forbidden riba, according to this rhetoric, is interest. To sell a product in Islamic finance, one must proclaim it to be interest free.

One should not be fooled by this rhetoric, however, even when advocates of Islamic finance announce that Islam does not recognize the time value of money. One needs only to recognize that scholars also accept that the credit price of an asset or commodity may be higher than its spot price. Moreover, Islamic scholars do not place any restrictions on the credit-price markup over the cash price, allowing one to incorporate time value, credit risk, interest rate risk, and other conventional components of financing charges. One must be careful, however, not to jump to hasty conclusions. For instance, a simple two-party sale buy-back would technically satisfy the provisions on using spot and credit sales of a nonmonetary commodity, but it would not be universally accepted as Islamic.

This practice is quite simple: Instead of lending you $1 million at 5% interest, I buy from you a property for $1 million and then sell it back to you at $1,050,000. In principle, the property need not even be worth $1 million on the spot market. Unfortunately, this practice is named in the Islamic Canon as a forbidden form of (or legal ruse for) riba. It is called bay` al-`ina, or `ina for short, meaning multiple trades of the very same property. This contract is in fact used extensively in Malaysia, where the practice is deemed permissible as long as the two sales are not stipulated in the same contract. However, it is not allowed in the vast majority of Islamic countries, including most notably the countries of the oil and cash-rich GCC.

One does not need to add much complexity to the structure to make it permissible, however. For instance, one may simply sell assets or commodities worth $1 million on credit for a deferred price of $1,050,000, even if one knows that the buyer will turn around and sell the assets or commodities for their spot price, thus effectively receiving the loan at 5% interest. Yes, surprising as this may be, and as many hours of consultants' time and religious rhetoric as one may have to endure, Islamic finance is—in the end—just that simple. It helps to know the names of the first contract (`ina) and the second (murabaha), which we shall discuss in the next section.

As one begins to consider progressively more complex structures, one invariably faces multiple choices of how to characterize a transaction with multiple components. Practitioners in Islamic finance learn to use the correct Arabic names to characterize those components for the purpose of Islamic certification, and to characterize them differently—if necessary—to adhere to regulatory and legal provisions in the relevant jurisdictions. This requires advanced legal-arbitrage skills, which are beyond the scope of this primer, and which the target reader may either possess or have the resources to acquire.

The second major prohibition in Islamic financial jurisprudence is even easier to finesse. Like riba, the forbidden gharar is not definitively defined in the Islamic canon or legal literature. Unlike riba, which is definitively forbidden, even if we are not entirely sure what would fall into that category, the forbidden gharar is left to the scholars' discretion. Indeed, classical and contemporary Islamic legal scholars have ruled that gharar, which is translated variously as uncertainty or risk, cannot be eliminated entirely. What is forbidden, therefore, is excessive and unnecessary gharar. In other words, the religious scholar must perform a cost-benefit analysis to determine if the economic benefit from allowing a transaction is sufficient to overcome the potential harm due to uncertainty that is present in the contract language or provisions.

This degree of Islamic legal discretion can eliminate the need for Islamic finance altogether. For instance, while the vast majority of Islamic jurists continue to disallow futures trading based on the prohibition of gharar, Malaysian jurists have permitted futures trading based on the argument that modern futures market and clearinghouse structures have eliminated excessive uncertainty. Retaining the prohibition of futures trading, however, may create a legal arbitrage opportunity. Classical Islamic jurisprudence permits credit sales, as we have already seen, as well as a prepaid forward contract known as salam. Conservative jurists thus like to say that Islamic law permits trading goods now for money later (credit sale), or money now for goods later (salam), but not goods later for money later (forward or future sale).

It does not take much skill to use spot sales, credit sales, and the salam sale to synthesize a forward contract. We have already seen how spot and credit sales can be used to synthesize a loan. All one needs is to use that structure to lend the salam buyer the present value of the forward price, and we have a synthetic forward.

Another interesting legal arbitrage opportunity applies to both gharar and riba prohibitions. Both prohibitions are only observed for commutative (that is, quid-pro-quo) financial contracts. Therefore, fixed income securities have been offered for decades in Egypt and Malaysia, under the name "investment certificates," based on guaranteeing only the principal. Interest is paid as a "gift," ostensibly unanticipated, which is based on economic conditions. This structure has not been adopted in other countries, but other noncommutative provisions, for instance, a unilateral promise to sell a property at lease end, have been used to circumvent other prohibitions. Moreover, the notion of noncommutativity has been used extensively to adopt the rhetoric of mutuality in Islamic insurance alternatives—known as takaful—even though to the best of my knowledge, there has not been any takaful provider that was in fact owned by its policyholders.

We review some of the main nominate contracts that are used as building blocks in contemporary Islamic finance. There are two reasons for the popularity of those nominate contracts. The first is an issue of authority. Contemporary Islamic scholars who are retained as consultants by Islamic financial providers generally lack the authority unilaterally to declare that a transaction is free of forbidden riba or gharar. This is partially avoided by referring to collective opinions issued by international Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh) academies. Still, the most common method to ensure legitimacy of a juristic pronouncement—in this Islamic common-law tradition—is appeal to precedent, which naturally lends itself to framing the question within the context of nominate contracts that were certified by earlier generations of jurists.

The second reason that nominate contracts have played such a prominent role in Islamic financial practice is that financial professionals often propose the initial structures for new services or products, which are then refined in collaboration with the retained religious-scholar consultants. It is much easier for financial professionals to design the new product or service using the building blocks of other products and services that were approved earlier, often by the same consultants. We will review some of the most commonly used building-block contracts of Islamic financial practice in this section, and then review some of their uses in contemporary Islamic finance in the following section.

The most basic contract, of course, is the sales contract. Classical Islamic jurisprudence distinguished between standard sales and what were called "trust sales." In the latter category, instead of negotiating a final price, the buyers rely on the sellers' truthful revelation of their cost of acquisition of the object of sale. The buyer and seller then negotiate the markup or markdown relative to the seller's invoice. The most common trust sale used in Islamic finance is the trust sale with a markup over invoice, known by the Arabic name muarabaha.

Murabaha was transformed from a simple markup-over-invoice sale into a mode of financing in the late 1970s, when it was combined with the permissibility of credit sales—known in Arabic by the name bay` bi-thaman 'ajil, although this terminology is generally used only in Malaysia. The first successful Islamic banking product introduced in the late 1970s was based on combining Murabaha, credit sale, and a third component: a binding promise by the customer to buy the property on credit from the bank.

Through a series of fatawa (religious opinions) by prominent Islamic jurists, the practice of murabaha financing was approved as follows. A customer wishes to finance the purchase of some asset or commodity. The Islamic bank may obtain a binding promise that the customer will buy the property on credit, at an agreed-upon markup above the spot price, which markup is characterized as the murabaha profit, rather than interest. With the promise in hand, the bank may then buy the property at its spot price, and then promptly sell it to the customer at the agreed-upon credit price. In some applications, the customer may serve as the bank's agent to purchase the property on its behalf and then to sell it to himself, thus reducing transaction costs and time delays.

Murabaha financing was also used by major Islamic banks starting in the late 1970s as a means of extending credit facilities to large corporate customers. It was characterized in this framework as a form of trade financing. The Islamic bank or financial institution would have a standing agreement with the corporate customer to finance the purchase of a certain amount of metal or other commodity with liquid spot markets. Whenever the customer needed credit, they would use the agreement to buy metal or commodities of a specific spot value at a credit price that is equal to the spot price plus a mutually agreed upon implicit interest charge. The customer may indeed need the purchased metal, in which case the transaction ends with this purchase. In other cases, the customer may actually be in need of cash, in which case it can turn around and sell the metal or other commodity at its spot price.

In some cases, especially in retail finance, the transaction costs of ownership transfer and multiple sales may be too large. There may also be basis risk due to movements in the commodity's spot price between the initial credit sale and the ensuing spot sale. In Malaysia, the buyer and seller would simply use `ina, described in the previous section, to sell a property on credit and then buy it back at the spot price. In the GCC, a more elaborate three-party alternative called tawarruq (literally, turning a commodity into silver, or monetizing it) has become a popular vehicle to extend financial credit.

Tawarruq financing often involves a standing agreement with a metals or other commodity trader. The financier buys the commodity on the spot, sells it to the customer on credit, and then sells it back to the dealer on the customer's behalf at the spot price (less any agreed-upon fees). The standing agreement and speed of transactions—three faxes or other communications sent in quick succession—can eliminate most of the transaction costs and basis risks. Depending on jurisdiction, the jurists may allow only dealing with domestic commodities traders, or add other warehousing restrictions to ensure that the traded commodity actually exists. However, actual physical receipt of the commodities was never made a requirement, allowing this transaction to emulate a credit facility by introducing trades of a real asset or commodity with minimal added cost.

Simple spot and credit sales can therefore be seen easily to emulate interest-based loans. The result of those transactions, however, is a pure financial debt, which the majority of Islamic jurists deem generally nontradeable. The majority of Islamic legal scholars allow selling the debt back to the debtor at a price below its face value—a practice known in Arabic as da` wa ta`ajjal, or discount for prepayment. However, if the debt is sold to a third party, it can be sold (transferred) only at face value, and only with the debtor's consent. The notable exception, again, is Malaysia, where trading debts at market value, known in Arabic as bay` al-dayn, is permitted. This allows Malaysian bankers to securitize debts and create secondary markets. However, those securities would not be acceptable to the religious scholars from other parts of the world, most notably from the cash-rich GCC. Consequently, other methods of securitization were required. One of the most popular securitization structures uses leasing, under the Arabic name ijara.

Ijara financing, like its murabaha sibling, was first approved by Islamic-banking scholars as an implicit mode of secured lending. If a customer wished to finance the purchase of a nonperishable asset (e.g., real estate, automobiles, or equipment), then the bank could buy the property and lease it to the customer. The bank may then give the customer an option to buy the property at an agreed-upon price at the end of the leasing period, thus converting the simple leasing arrangement into a versatile financial tool. The majority of jurists insist that the lessor in this arrangement must retain substantial ownership of the leased property, rendering the transaction an operating rather than a financial lease. This, of course, can have varying tax implications for the implicit interest (financing) charge. From a logistical point of view, lessor obligations for insurance, maintenance, and the like are handled most often through side agreements with special purpose vehicles.

An interesting by-product of the insistence on lessor-ownership of the underlying property has been the ability to securitize lease-generated receivables. The lease is often conducted through a special purpose vehicle (SPV) at any rate—for a variety of tax, regulatory, and bankruptcy-remoteness purposes. Shares in that SPV would entitle the shareholders to the stream of rental payments. More importantly, lessor SPV shares are deemed by the religious scholars to represent ownership of the underlying asset itself, not merely the rent receivables. Thus, the scholars allow trading those shares, often marketed over the past few years under the name sukuk al-ijara, or rent certificates. This structure has been the workhorse of the fastest-growing segment of Islamic finance: the issuance of bond alternatives known collectively as sukuk.

Interestingly, since sukuk are generally issued as common shares in a special purpose vehicle, they can be advertised as containing an element of partnership, which resonates well with Islamist rhetoric on ideal Islamic finance being based on partnership and profit-and-loss sharing. There are two main partnership models that are discussed at length in Islamic economics and finance. Simple partnership or musharaka requires that losses are shared in proportion to capital contributions, but profits can be shared according to any agreed-upon formula. The other form of partnership discussed at length in Islamic economics and finance is silent partnership, known by the Arabic name mudaraba. In this structure, the investor or principal provides all the capital and bears all financial losses, but financial gains are shared with the entrepreneur or agent.

For retail as well as investment banking products, Islamic scholars have allowed the financing rate (characterized as profit in credit sales and rent in leases) to be benchmarked to conventional interest rates. The industry is dominated by English bankers, and therefore the benchmark of choice has been the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). In sale-based structures, the financing rate is fixed for the duration of the financing facility. In lease-based structures, an added degree of flexibility allows the lessor and lessee to adjust the rent, usually tracking LIBOR by adding a simple spread thereupon.

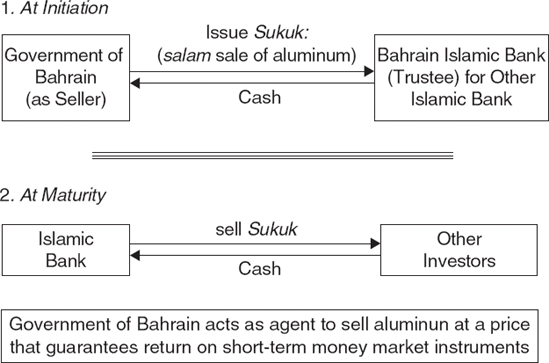

Sukuk structures that rely on long-term leases are not particularly efficient for short-term debt instruments, since the transaction costs and tax burdens may be substantial. Therefore, commodity-sale based structures were introduced for short-term debt instruments. The contract of choice in this case, especially as used by the Bahrain Monetary Agency to issue Treasury bill-like instruments, has been the prepaid forward contract salam. The government would collect the Treasury bill prices by ostensibly selling a commodity, usually aluminum or other metal, forward. Instead of delivering aluminum at the Treasury bill maturity, the government guarantees that it will sell the aluminum on behalf of the bill-holders at a price equal to the initial price that they paid plus the appropriate interest rate on its short-term debt. This structure is shown in Figure 10.1.

Other vehicles were also devised, using what is known as parallel-salam. Under that structure, a three-month bill can be structured by selling aluminum forward, say, six months, with the price payable now. In three months, the parties may engage in a reverse three-month prepaid forward contract, whereby the obligations to deliver the commodity at the coinciding maturity dates of the two salam sales cancel each other out. The price of the second reverse salam, of course, would be the price of the first salam plus the appropriate quarterly interest on short-term debt.

Other classical nominate contracts are sometimes used, e.g., istisna`, or commission to manufacture, is a popular analog to salam, where the price is prepaid, possibly in installments, as the object of sale is actually manufactured or constructed. This structure is popular for infrastructure and other construction projects, and often combined with leasing to create a build-operate-transfer (BOT) structure that mimics the financial structures of conventional practice.

Classical conditions of leasing, which allow some types of subleasing, have allowed timeshare agreements to be used under the name sukuk al-intifa`, or usufruct securities. Juristic bodies, for example of AAOIFI, have produced lists of permissible contracts and basic structures, both classical and modern (e.g., salam itself is a classical contract, sukuk al-salam and parallel salam as financial tools are modern inventions).

Financial professional who are newcomers to Islamic finance can accomplish much using only simple sales, credit sales, and leases. As they contemplate more complex structures (e.g., shorting assets) or as they aim to reduce transaction costs to gain a competitive advantage in this market, they may consult the lists produced periodically in AAOIFI's Shari`a Standards publications to find appropriate building blocks for their structures. As they become more advanced still and need to devise new building blocks, they can get their religious-scholar consultants to approve those structures, and then possibly to add them to the list of AAOIFI standards, as the same scholars who serve as consultants for the banks are the ones who serve on AAOIFI's Shari`ah advisory board.

Derivative securities such as swaps, options, and futures have become essential parts of today's financial world. They are used to hedge various risks, as well as to leverage financial exposure to make it sufficiently attractive to investors. In Islamic finance, call options have been synthesized from a classical contract known as `urbun— literally, down payment on a purchase. The down payment is treated as the call premium, and the exercise price is the difference between the original price and that down payment, which the buyer pays if he chooses to exercise the option. We have already seen how a forward contract can be synthesized from the classical prepaid forward contract, salam, and a credit facility generated by spot and credit sales. It then follows by put-call parity that we can synthesize a forward contract from the synthetic call and the synthetic forward (long put = short forward + long call). In addition, while the majority of Islamic jurists continue to forbid trading in options, they allow offering the options as unilaterally binding promises that are ostensibly noncommutative. Practitioners in Islamic finance use a combination of synthetic and noncommutative characterizations to include options in hedging mechanisms, as was the case, for instance, in the recent issuance of U.S. $166 million "East Cameron Gas Sukuk" in July 2006.

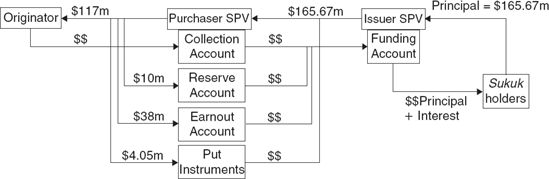

The East Cameron Gas Sukuk was rated CCC+ by Standard & Poor's, and it pays 11.25% for the duration of its 13-year tenure. The originator of the sukuk is the Houston-based East Cameron Partners, an independent oil and gas exploration and production company. The issuer is an SPV called East Cameron Gas Company, incorporated in the Cayman Islands. The deal was primarily arranged by Bemo Securitization (BSEC), of Beirut, Lebanon, in cooperation with Merrill Lynch. Bemo had earlier arranged for a well-publicized issuance of Islamic lease-based sukuk for the rental car fleet of the Saudi company Hanco. The bulk of the East Cameron sukuk were initially envisioned for sale in the GCC countries. However, it was reported that a large portion of those sukuk were, in fact, bought by conventional hedge funds.

This sukuk issuance received significant media coverage because it was the first originated by a U.S. company. However, it must be noted that similar financial structures had been used by Islamic investment banks and private equity firms for leveraged buyouts in the United States. The standard sale-leaseback sukuk structure was not viable for the East Cameron Gas issuance because the fixed assets eligible for leasing (mainly rigs) were not of sufficient value to generate the desired Dollar amount. The SPV was thus characterized as a co-owner of the originator's assets (in a musharaka). A reserve account was used to cover potential shortage in collected revenues from the originator, thus nearly guaranteeing a fixed rate of return to the issuer SPV, and hence to the sukuk holders. Put instruments were also used to protect the sukuk-holders from the bulk of ownership risks that would entail sharing in profits and losses. In the meantime, co-ownership of the company's assets allows secondary-market trading of those sukuk.

A simplified schematic structure of this issuance is shown in Figure 10.2.

BSEC's director said that they could have achieved an investment-grade rating for the issuance, but it would have taken longer to develop the structure. This is ultimately the trade-off that participants in Islamic finance have to examine: quick but inefficient structures, or more efficient ones that require more time and legal fees. It is no wonder that hedge fund managers were happy to buy the East Cameron Gas Sukuk at a yield commensurate with CCC+ rating, when the credit rating of a conventional bond would have been higher. Then, again, there are a host of legal risks associated with those new structures, and the higher yield may—in part—compensate for the resulting uncertainty.

This short introduction did not provide a comprehensive survey of all products and services in the Islamic finance space. For example, there are a number of screening methodologies, pertaining to lines of business and debt structures, that are used in selecting stocks and companies in which Islamic mutual funds and private equity firms can invest. The tricky financial aspects of setting up investment vehicles, however, pertain to structuring derivatives, credit facilities, and other contract-based structures that are introduced in this chapter. I hope to have shown that the logistical and informational barriers to entry into Islamic finance are actually quite low. It is a theorem that every financial practice can be adapted for the Islamic market as it exists today. Financial providers' considerations in this adaptation are usually restricted to transaction costs of structuring the deal, and the marketability of the product. However, it must be noted that the relative ease of entry into this market segment is a mixed blessing. It means that one can easily bring structured products to market with combinations of simple and well-understood contracts. However, this very ease with which new products can be brought to market masks considerable inefficiencies and poorly understood legal risks, which must be a concern for careful financial providers.

Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (2004). Shari`a Standards, 1424–5H/ 2003–4, Manama, Bahrain: AAOIFI.

Al-Zuhayli, W. (2003). Financial Transactions in Islamic Jurisprudence (Volumes I and II), Damascus: Dar Al-Fikr (M. El-Gamal, tr.).

El-Gamal, M. (2000). A Basic Guide to Contemporary Islamic Banking and Finance. Plainfield, IN: Islamic Society of North America, 2000.

El-Gamal, M. (2006). Islamic Finance: Law: Economics, and Practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Henry, C., and Wilson, R.(eds.)(2004). The Politics of Islamic Finance. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Kamali, M. H. (2000). Islamic Commercial Law: An Analysis of Futures and Options. Cambridge: Islamic Texts Society.

Kuran, T. (2005). Islam and Mammon: The Economic Predicaments of Islamism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lewis, M., and Algaoud, L. (2001). Islamic Banking. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Maurer, B. (2005). Mutual Life, Limited: Islamic Banking, Alternative Currencies, Lateral Reason. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Saeed, A. (1996). Islamic Banking and Interest: A Study of the Prohibition of Riba and Its Contemporary Interpretation. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

Usmani, M. T. (2002). An Introduction to Islamic Finance. Berlin: Springer.

Vogel, F., and Hayes, S. (1998). Islamic Law and Finance: Religion, Risk, and Return. Berlin: Springer.

Warde, I. (2000). Islamic Finance in the Global Economy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.