FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

ANAND K. BHATTACHARYA, PhD

Managing Director, Countrywide Securities Corporation

WILLIAM S. BERLINER

Executive Vice President, Countrywide Securities Corporation

Abstract: Mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) are constructed by aggregating large numbers of similar mortgage loans in mortgage pools. There are two mechanisms for secu-ritizing MBS pools; they can be issued by governmental agencies and quasi-agencies (that is, the government-sponsored enterprises, or GSEs) as agency pools, or structured with separate credit enhancement as "private-label" securities. MBS trading conventions reflect the nature of mortgage lending. Loans begin as an application that is "locked" at some point prior to the loan's closing date, while it is being underwritten and processed. Trading in many securities is done on a forward basis, where trading is executed to settle at some date in the future. This trading convention also implicitly creates a financing vehicle, where securities can be financed in an efficient and inexpensive fashion. CMOs are created by carving up MBS principal and interest cash flows in order to target the needs of specific investor clienteles. As MBS pools are closed universes of cash flows, structuring involves transferring prepayment and (for private-label structures) credit risk within the deal, with the goal of maximizing the deal's proceeds while better meeting the objectives and preferences of various investor constituencies.

Keywords: mortgage-backed securities (MBSs), private-label securities, agency securities, senior pass-throughs, credit enhancements, guaranty fee, structured securities, tranching, collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), mortgage strips, base servicing, excess servicing, government sponsored enterprises, agencies, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Ginnie Mae, weighted average coupon (WAC), subordination, shifting-interest structures, overcollateralization, forward market, dollar roll.

This chapter provides an overview of mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) and the markets in which they trade. It discusses the mechanics of issuing different forms of MBS, along with many of the market practices, conventions, and terms associated with the MBS markets.

The fundamental unit in the MBS market is the pool. At its lowest common denominator, mortgage-backed pools are aggregations of large numbers of mortgage loans with similar (but not identical) characteristics. Loans with a commonality of attributes such as note rate (that is, the interest rate paid by the borrower on the loan), term to maturity, credit quality, loan balance, and product type are combined using a variety of legal mechanisms to create relatively fungible investment vehicles. With the creation of MBS, mortgage loans were transformed from a heterogeneous group of disparate assets into sizeable and homogenous securities that trade in a liquid market.

The transformation of groups of mortgage loans with common attributes into tradable and liquid MBS occurs using one of two mechanisms. Loans that meet the guidelines of the agencies (that is, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae) in terms of credit quality, underwriting standards, and balance are assigned an insurance premium, called a guaranty fee, by the agency in question and securi-tized as an agency pool. Loans that either do not qualify for agency treatment, or for which agency pooling execution is not efficient, are securitized in nonagency or "private label" transactions. These types of securities do not have an agency guaranty, and must therefore be issued under the registration entity or "shelf" of the issuer. As noted later in this chapter, the insurance (or "credit enhancement") for the loans is in the form of either a private guaranty or, more commonly, structured in the deal through so-called "subordinate" classes.

The senior portions of these deals are very similar in profile to agency pools, and are often referred to as private-label or senior pass-throughs. The term "pass-through" indicates that principal and interest is passed on to the investor pro rata with their holding. Using this definition, the senior portion of a private label deal is technically not a pass-through, because principal is redistributed within the structure; however, the term is nonetheless utilized to describe the senior cash flows before they are restructured.

Once a pool (in either agency or private-label form) is created, it can be sold to investors in the form of a pass-through, in which principal and interest is paid to investors based on their pro rata share of the pool. However, the cash flows of pools can also be carved up to meet the requirements of different types of investors. The creation of so-called "structured securities" involves dividing (or "tranching") the underlying pools' cash flows into securities that have varying average lives and durations, different degrees of prepayment protection or exposure, and (in the case of private label deals) different degrees of credit risk. These types of securities are broadly referred to as collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs). The flexibility inherent in tranching, along with the broad range of loan instruments, allows the MBS market to reflect a large degree of market segmentation. In turn, this allows a wide range of investor types with different investment objectives and risk tolerances to invest in the MBS market, supplying the funds that ultimately are recycled into new mortgage lending.

It will be helpful at this juncture to briefly discuss and contrast the processes of creating and structuring agency CMOs and private label transactions. To create an agency CMO deal, the underwriter buys agency MBS pools in the primary or secondary markets and places them in a trust-like entity. The different tranches are then created from the principal and interest cash flows generated by the MBS pools (or "collateral"). In contrast, private label transactions are created by placing large numbers of loans directly in a securitization vehicle, from which the structured transaction is subsequently created by the issuer. (This accounts for why these transactions are sometimes referred to as "whole loan CMOs." CMOs are also referred to as real estate mortgage investment conduits, or REMICs. The terminology refers to a provision in the Tax Reform Act of 1986 in order to remedy some double taxation inefficiencies inherent in earlier collateralized structures. While the term "REMIC" is essentially a tax election, often the terms "CMO" and "REMIC" are used interchangeably.) While the agency transaction is an arbitrage of sorts, the private-label securitization serves as the process by which loans are directly distributed into the capital markets.

A different subset of the MBS sector is the market for mortgage strips, or more precisely the market for principal-only and interest-only securities. Since mortgages are comprised of both principal and interest, the two components can be separated and sold independently. The holder of the principal-only security (or PO) receives only principal (scheduled and unscheduled) paid on the underlying loans. The holder of the interest-only security (or IO) receives the interest generated by the underlying loans. Although IOs are quoted with a principal balance, this balance is notional in nature; it is used only as a point of reference for settling the transaction and calculating monthly interest cash flows generated by the security. The most common mortgage strips are created simply by putting agency pools into a trust and splitting principal and interest cash flows into IOs and POs. (Note that IOs in this context should not be confused with interest-only loans; the two concepts are totally different, even though they do share some of the same nomenclature.)

The market for mortgage developed to allow MBS investors a means of trading directly on prepayment speeds and expectations. POs typically have long positive durations and rise in value when rates decline, while IOs have negative durations, behaving in a fashion similar to bond puts when rates rise. However, the critical driver of performance strips is prepayment expectations. POs perform well if prepayment speeds are fast, in the same way that returns would be enhanced if a zero-coupon bond were called prior to maturity at par. By contrast, IOs perform well if prepayment speeds are slow; they can be viewed as an annuity where the value increases the longer it remains outstanding.

While IOs and POs are most commonly created in trust form, both types of bonds can also be created as part of a CMO deal. Structured IOs and POs have a similar appeal to investors as strips, and are evaluated in a similar fashion. They are created as part of the process of structuring certain bonds with a targeted coupon or dollar price. If an investor seeks a bond with a lower dollar price, for example, the coupon on the bond must be reduced; this can be accomplished by stripping some coupon off the tranche in question and selling it as a structured IO.

While both agency adjustable rate pools and private label securities have existed for many years, the agency fixed rate market remains the most widely quoted and liquid benchmark in the MBS market. Therefore, a discussion of pooling practices and the securitization process logically begins with the formation of fixed rate agency pools. In this section, we will first address the basics of agency fixed rate pools, which dictate to a large extent how such pools are created. Subsequently, we will discuss the creation of adjustable rate mortgage (ARM) pools, which have many similarities to fixed rate products but are pooled quite differently.

Fixed Rate Agency Pooling

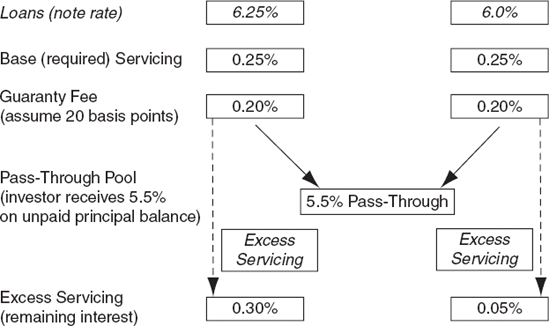

Agency fixed rate MBS are traded according to their coupons, which are normally securitized in 50 basis point increments. There are liquid markets in both even coupons and half-coupons (e.g., 6.0% and 6.5%), although quarter- and eighth-coupon pools are sometimes originated. Loans, by contrast, are normally originated in increments of 12.5 basis points (or one-eighth of a percent). As part of the transformation process, certain cash flows from the loan interest stream are allocated for servicing and credit support payments. These apportionments are as follows:

Guaranty fees (or "g-fees") are, as described earlier, fees paid to the agencies to insure the loan. Since these fees essentially represent the price of credit risk insurance, g-fees vary across loan types. In the conventional universe, g-fees vary depending on the perceived riskiness of the individual loans (based on credit metrics such as credit score, loan-to-value (LTV) ratio, and documentation). However, high-volume lenders may be able to negotiate generally lower guaranty fees. For Ginnie Mae pools, the guaranty fee is almost always six basis points, reflecting the loan-level guarantees provided by the Federal Housing Administration and Veterans Administration.

Required servicing or base servicing refers to a portion of the loan's note rate that must be held by the servicer of the loan. This entity collects payments from mortgagors, makes tax and insurance payments for the borrowers, and remits payments to investors. The amount of base servicing required differs depending on the agency and program. At this writing, base servicing is 25 basis points in the fixed rate pass-through market.

Excess servicing is the amount of the loan's note rate in excess of the desired coupon remaining after the g-fees and base servicing are subtracted.

Both base and excess servicing (sometimes described as mortgage servicing rights or MSRs) can be capitalized and held by the servicer after the loan is funded. However, secondary markets exist for trading servicing, either in the form of raw mortgage servicing rights or interest-only securities created from excess servicing.

A simple schematic showing how two loans with different fixed note rates can be securitized into a 5.5% agency pass-through pool is shown in Figure 32.1. For both loans, the amount of base servicing and guaranty fee is the same, with the difference being the amount of excess servicing created by the issuer. This diagram ignores some of the complexities of pooling, however, which will be addressed later in this section.

Figure 32.1. Cash Flow Allocation for a 5.5% Agency Pass-Through Pool for Loans with Different Note Rates

General pooling practices in the fixed rate market mandate that the note rate of the loans must be greater than the pool's coupon. However, loans with a wide range of note rates can be securitized in pools. For example, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae allow the note rate to be as much as 250 basis points higher than the coupon rate. Ginnie Mae pooling rules depend on the program used to securitize the loans. The Ginnie I program, where the majority of loans are pooled, requires that the note rate be 50 basis points over the coupon rate. The multi-issuer Ginnie II program allows the note rate to be up to 150 basis points higher than the coupon.

Pooling economics normally dictate that the note rate of the loan is between 25 and 75 basis points higher than the coupon rate since retaining large amounts of excess servicing is generally uneconomical. In addition, guaranty fees can be capitalized, or "bought down," and paid as an up-front fee to the GSE at the loan's funding. This typically occurs when the lender wishes to create pools with relatively high coupon rates (e.g., pool a 6.25% loan into a 6.0% pool) based on market conditions, a practice known as "pooling up." (Naturally enough, pooling this loan into a 5.5% pool would be called "pooling down.") Because of the base servicing requirement, however, at this writing the spread between a loan's note rate and pooling coupon cannot be less than 25 basis points.

Once large numbers of loans are funded, lenders will group loans with the same coupon in order to form pools. To create a pool, the lender effectively transfers loans earmarked for a particular coupon to the agency and receives the same face value of MBS in exchange. The MBS received may consist of a pool collateralized by only its loans, or it may be part of a multi-issuer pool. After receiving the security, the lender can either sell the pool into the secondary market or (in the case of a depository) hold it in its investment portfolio.

The GSEs also buy loans for cash proceeds through what is called, appropriately enough, the cash window. This is often used for loan programs with unusual specifications such as certain documentation styles or loan-to-value ratios, as well as by smaller lenders that engage in piecemeal sales. Loans purchased through the cash window can either be securitized in multi-issuer pools or retained in the GSEs' portfolios.

Adjustable Rate Agency Pooling

As noted earlier in this section, pooling practices in the agency ARM market are currently somewhat different. As in the fixed rate market, a standard amount of base servicing is held on each loan, and guaranty fees are assigned and paid on the loans based on each loan's perceived riskiness. (Base servicing in the ARM market has historically been 37.5 basis points, but at this writing some lenders have begun to hold only 12.5 basis points of base servicing.) The lender's current production, with loans having a range of note rates, is then pooled, with the pool's coupon being an average of the net note rates in the pool weighted by the loans' balances. This is referred to as having a weighted average coupon or WAC. Using this methodology means that:

No excess servicing is held in order to decrease the net note rates of the loans to a targeted level.

G-fees are generally not bought down, since buydown pricing is not efficient in the ARM sector.

Pools will contain loans with note rates below the coupon rate.

There are important implications of this different pooling methodology. ARM pools typically are originated with uneven coupons taken to three decimal places (e.g., a pool might have an initial coupon of 5.092%). In addition, coupon rates on ARM pools (and, in fact, any security with a WAC coupon) change slightly over time, as individual loans in the pool are paid off. The result of these factors is that agency ARMs trade on a pool-specific basis, rather than by specific coupons as in the fixed rate universe. (There have been a number of initiatives designed to create ARM securities that can trade in forward markets more like those of the fixed rate universe, although none have yet been adopted in a broad fashion.)

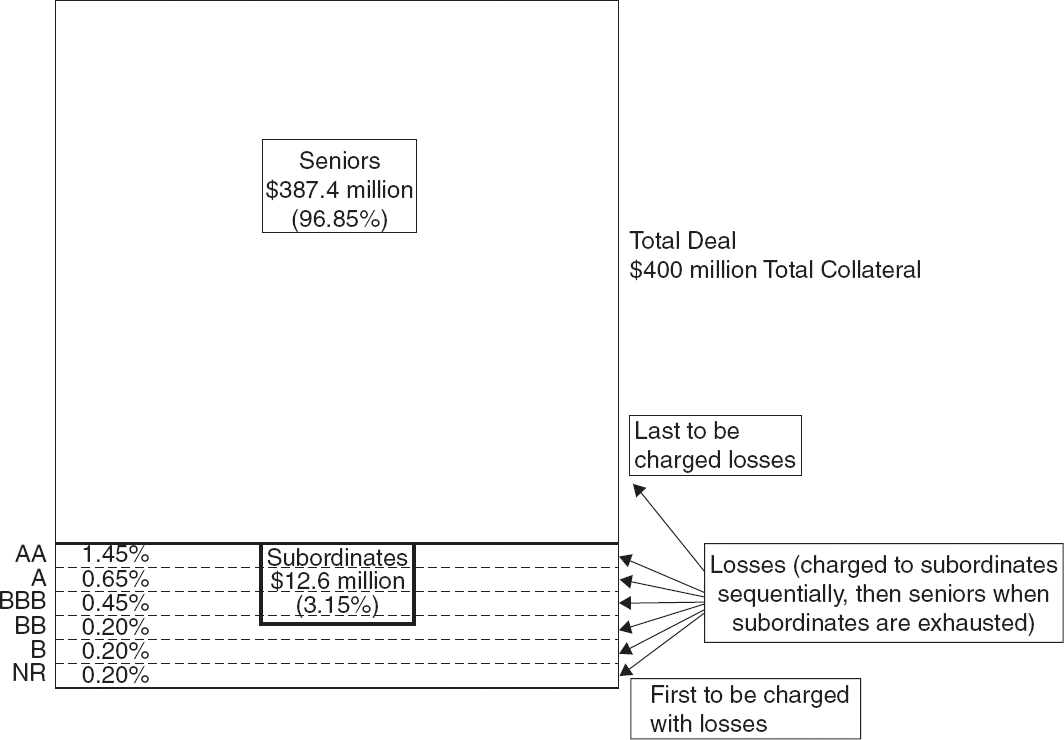

While the creation of private-label deals is conceptually similar to agency pooling practices, the lack of involvement by the agencies necessitates significant differences. Since there is no guaranty fee, alternative forms of credit enhancement must be utilized as noted previously. Private credit enhancement is most commonly created in the form of subordination, which means that a portion of the deal is subordinate or "junior" in priority of cash flows, and is the first to absorb nonrecoverable losses in order to protect the remaining (or "senior") tranches. A common technique is to divide the subordinated part of the deal into different tranches, each with different ratings (which typically range from double-A to unrated first-loss pieces) and degrees of exposure to credit losses. (For example, the nonrated "first loss" tranche is the first to absorb losses; if this tranche is exhausted, the losses are then allocated to the tranche second-lowest in initial priority). Subordinate tranches trade at significantly higher yields than the seniors to compensate investors for the incremental riskiness and greater likelihood of credit-related losses.

Figure 32.2 shows an example of a senior/subordinate deal structured in this fashion. The amount of subordination required for a deal and the relative sizes of the different subordinate tranches (often referred to as the "splits") are dictated by the rating agencies, based upon their assessment of the likelihood of losses for the subject collateral. Prior to being structured, the senior portion of the deal in the example has cash flows that are very similar (but not identical) to agency pools, as noted previously. These private label pass-throughs are sometimes sold directly in unstructured form, although it is more common to see them restructured into tranches.

Deals with subordination (also called senior/sub deals) typically have an additional feature designed to insure the adequacy of credit enhancement levels. All unscheduled principal payments (that is, prepayments) are initially directed to the senior tranches, and the subordinates are locked out from prepayments (although they do receive scheduled principal payments, or amortizations). This feature causes the subordination (as a percentage of the deal) to grow over time, and increases the degree of protection for the senior sector. The subordinates eventually begin to receive some unscheduled principal payments (although the actual schedule depends on the type of collateral), and ultimately receive prepayments pro rata with their size. The technique is referred to as "shifting interest," and deals with this type of subordination are commonly called shifting-interest structures.

Other variations of the senior/subordinate structure are used in the MBS markets, especially for subprime and other loans that have a greater degree of default risk. Some deals are structured such that there is more loan collateral than bonds in a deal, lending additional credit support to the senior bonds (in addition to some subordinate classes). This structuring technique is referred to as overcollateral-ization, and deals structured in this fashion are referred to as OC structures.

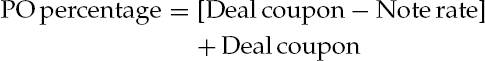

As with agency ARM pools, private label deals typically securitize a wide range of note rates, due in part to the desire of issuers to capitalize on economies of scale by issuing large deals. However, the market for fixed rate securities is generally not receptive to WAC coupons. In order to create a fixed coupon rate, the loan collateral must be modified before the credit enhancement is structured. This technique is somewhat different from that utilized in creating agency pools. Both the range of note rates included in a deal, as well as the desire to include loans with note rates below the deal's coupon (once base servicing and fees are taken into account), necessitate the creation of WAC IOs and POs, securities unique to the private label market.

The decision with respect to which coupon is to be produced is a function of market conditions, including investor's interest rate and prepayment outlook. Once the coupon is designated, the loans are divided into "discount" and "premium" loan groups. This calculation subtracts the base servicing and fees from each loan's note rate to create the net note rate. The net note rate is then compared to the deal's designated coupon. Discount loans are those loans that have a net note rate lower than that of the deal's coupon; premium loans are those where the net note rate is above the deal coupon.

At this point, the two loan groups are each structured to give them the deal's coupon. The discount loans are "grossed up" to the deal's coupon rate by creating, for each note rate, a small amount of PO. (By creating some PO for each strata, the available interest is allocated over a smaller amount of principal, effectively raising its net note rate to that of the deal coupon.) The amount of PO created for each rate stratum is computed based on the PO percentage, which is calculated as follows:

The PO percentage for each note rate stratum is then multiplied by its face value, and the sum of the POs created for all discount note rates is the size of the WAC PO.

The loans in the premium loan group are stripped of some of the interest in order to reduce their net note rates to that of the deal coupon. The interest strip is assigned a notional value equal to the face value of the stratum. As an example, assume that $20 million face value of loans has a 6.5% note rate, and the designated deal coupon is 6.0%. Assuming 25 basis points of base servicing and no fees gives it a 6.25% net note rate. Therefore, 25 basis points of interest is stripped from these loans, creating $20 million notional value of a strip with a coupon of 0.25%. The notional value of the WAC IO is simply the combined notional value of all loans having premium net note rates, and its coupon is the average of the strip coupons weighted by their notional balances. (Note that in some cases the strip cash flows generated by the premium loans are held by the originator in the form of excess servicing, rather than securitized into a WAC IO.)

The breakdown and grouping of loans backing a hypothetical private label deal, and the structuring of the loans into a pool with one fixed coupon rate, is shown in Table 32.1. The table shows the calculations for a package of loans with various note rate strata for a deal with a 5.75% coupon, assuming 25 basis points of base servicing and 0.9% trustee fee (which are both standard assumptions at this writing). All loans with note rates of 6.125% and higher are considered premium loans, since they will have a net note rate higher than the 5.75% cutoff; loans with note rates below 6.125% are classified as discount loans. Notice that changing the deal's coupon changes the sizes of the WAC IO and PO, as well as the WAC IO's coupon. In the example, lowering the deal coupon to 5.5% pushes $82 million face value of loans, with note rates of 5.75% and 5.875%, into the premium sector, increasing the WAC IOs notional face value from $333.5 million to $415.5 million. The face value of the WAC PO declines, however, from approximately $7.21 million to $2.72 million. Therefore, the "market conditions" influencing the choice of coupon include the preferences of investors for premium or discount coupons, as well as the relative demand for IOs and/or POs.

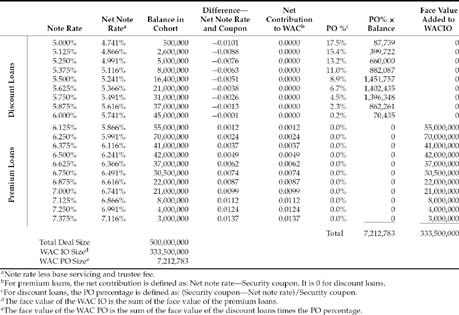

The structure of the MBS markets has long reflected the practices of both originators and borrowers in the primary mortgage market. This discussion is facilitated by a brief overview of the timeline of a mortgage loan, illustrated in Figure 32.3. A loan begins as an application, which may either be associated with a designated rate (making the loan "locked" or "committed") or carried as a floating rate obligation (to be locked at a point prior to funding). Borrowers that lock their loan at the time of application pay slightly more for their loans (in terms of either a rate differential or slightly higher fees) to account for the cost of hedging the loan for the period between application and funding. Most importantly, there is a lag between the points in time when borrowers apply for their loans and the loans are funded that lenders must take into account in managing their book of business, or pipeline. This lag reflects the time necessary for lenders to underwrite the loan and process the paperwork, which includes appraisals, title searches and insurance, geological and flood surveys, and credit analysis. In addition, purchase transactions often require additional time to process and register the underlying real estate transaction.

The lag between application and funding, which varies depending on the type of loans and market conditions, allows lenders to sell their expected production for settlement in the future. However, it also forces lenders to manage and hedge their production pipeline in order to control the variability of their proceeds and maximize their profitability. While hedging a loan pipeline is similar in concept to hedging other portfolios, it requires lenders to continuously be appraised of the rate of new applications (which adds to the position) as well as so-called "fall out," which occurs as some borrowers allow their loan applications to lapse. A fairly consistent amount of loans will fall out under all circumstances, reflecting transactions that fail to close for a variety of reasons. However, fallout of committed loans can change sharply if lending rates fluctuate. For example, a drop in rates typically causes an increase in the number of loans that fall out as applicants let their existing application lapse and apply for new loans. In the same fashion as negative convexity occurs with mortgage loans, changing fallout rates complicate the process of hedging by making changes in the pipeline's value nonlinear with respect to interest rates.

The need for lenders to sell their expected production for future settlement has resulted in the MBS market being structured as a so-called forward market. In a forward market, a trade is agreed upon between two parties at a price for settlement (that is, the exchange of the item being traded for the agreed-upon proceeds) at some future date.

The MBS market has evolved a number of conventions unique to the needs of both mortgage originators and investors. For example, settlements occur each month according to a predetermined calendar which specifies the delivery date for a variety of products over the course of each month. (The calendar is developed by the Bond Market Association (BMA) and published roughly six months in advance.) Prices are typically quoted for three settlement months (e.g., a quote sheet in March would post prices for April, May, and June settlement). However, trades can be executed farther in the future, subject to accounting and counterparty risk considerations.

Transactions in fixed-rate pass-through securities can be effected in one of three ways:

A preidentified pool or pools can be traded. In this type of "specified pool" trade, the pool number and "original balance" of the pool (that is, the amount of the pool as if it were a brand-new pool, before the effects of paydowns) are identified at the time the transaction is consummated.

A so-called to-be-announced (TBA) trade. In this case, the security is identified (e.g., Fannie Mae 6.0s) and a price is set; but the actual pools identities are not provided by the seller until just before settlement. (This process is referred to as pool allocation.) The attributes of the pools that are eligible for delivery into TBA trades is specified by the BMA in order to effect a degree of standardization.

A "stipulated" trade. This is a variation on a TBA trade, but the underlying characteristics of the pool are specified more precisely than in a standard TBA trade. In some cases, the pools in a stipulated trade are not deliverable, under the BMA rules, into TBA pools. In other instances, the pools can be delivered, but are viewed as having incremental value to investors and trade at a premium to TBAs.

The TBA market only exists, at this writing, in the fixed rate market for agency pools. As noted previously, there is currently no equivalent to the TBA in the ARM market for conventional ARMs because of the wide variety of product types and specifications in the ARM market. (There has been a TBA market in the Ginnie ARM product, but trading in that sector became fairly illiquid in the late 1990s.) ARM products trade almost entirely as either specified or stipulated (or "stipped," as it is sometimes called) pools, although they generally settle based on "good-day" delivery specified by the BMA calendar. Both agency and private label deals are settled at the end of the month; secondary trading typically occurs for settlement three business days after the trade is executed, for so-called "corporate settlement."

An interesting attribute of forward markets that has appeal to MBS participants is the fact that they implicitly create a built-in financing vehicle. The forward market mechanism allows trading in the same securities for settlement in different months. As noted, originators generally sell their production for forward settlement in order to monetize and hedge their pipelines. However, there is also demand for MBS pools for settlement in the early or "front" months. For example, some types of investors (such as depository institutions) generally put securities on their books rather than forward obligations, which may not receive favorable accounting treatment. In addition, dealers acquiring agency pools as collateral for agency CMO deals must take delivery of the pools before their structured transaction settles. Therefore, MBS trading involves pricing the same securities for different settlement dates. In addition, dealers make active markets in TBAs for different settlements, simultaneously buying positions for one settlement month and selling the identical position for another. This type of transaction is known as a dollar roll or simply a "roll."

Simply put, valuing dollar rolls involves weighing the benefits and costs, over a holding period, of either:

Buying the security for the earlier (or "front") month, and owning (and financing) it for the period ending with the latter (or "back" month) settlement date.

Buying the security for the back month's settlement.

In the first case, where the security is bought for the front month, the investor receives coupon payments and reinvested interest for the holding period, along with principal payments (both amortizations and prepaid principal). The investor must also finance the position, typically through the repurchase market. In theory, the back month price is such that the investor is indifferent between the two alternatives. In practice, the price difference (or "drop") between the two settlement dates is often greater than that implied by the break-even calculation, which means that the investor buying the position for back-month settlement is effectively financing the security at an implied repo rate lower than that available in the repurchase market.

As noted previously, the cash flows generated by agency pools and senior private-label pass-throughs are very similar in nature. Both securities can be structured to take advantage of demand for a variety of securities by different segments of the fixed income investment community. Various investor clienteles have different investment objectives and risk tolerances, and thus tend to invest in securities with different cash flow and performance attributes. Some different market segments include:

Banks and other depository institutions, which generally seek short securities where they can earn a spread over their funding costs.

Life insurance companies and pension funds, which typically invest in bonds with longer maturities and durations in order to immunize long-dated expected liabilities.

Investment managers, who typically manage fixed income assets versus performance indexes.

Hedge funds, which typically seek investment vehicles that offer the potential for very high-leveraged returns.

The nature of mortgage cash flows makes mortgage loans and mortgage-backed securities ideal vehicles for creating a variety of bonds. Their long-term principal and interest cash flows allow structurers to create securities of varying average lives and durations in order to meet the needs of different classes of investors. In addition, different structures allow different risks (both prepayment and, for private-label deals, credit) to be transferred within the structure, and creates a rich environment for the wide variety of structures and structuring techniques available. For a discussion of MBS structuring, see Chapters 5 through 8 of Fabozzi, Bhattacharya, and Berliner (2007).

However, mortgage structures are closed universes by nature, in that all balances and cash flows generated by the collateral within the structure must be taken into account. For example, a structure where the coupon of one bond is stripped below that of the collateral must allocate the incremental interest cash flows elsewhere in the structure. This shifting of interest cash flows can be done in a number of different forms (see Fabozzi, Bhattacharya, and Berliner (2007)). Another example might be a bond that pays principal to investors based on a schedule. This stabilizes the "scheduled" bond's average life and duration, but cash flow uncertainty is transferred to other bonds in the structure, giving their cash flows greater variability.

Therefore, the process of MBS structuring requires examining and valuing the trade-offs necessary to create a variety of bonds designed to meet the needs of multiple investor clienteles. To create a more desirable bond within a structure, for example, the underwriter must be able to sell the enhanced bond (or combination of bonds) at a better valuation than the original tranche, in order to offset the concession that must be given to attract investors to the bond with less appealing attributes. Understanding the trade-offs involved in structuring therefore requires an understanding of how the different structuring techniques work, and how they impact other bonds within the structure.

The market for mortgage-backed securities is the largest cash securities market in the world, and is almost half again as large as the Treasury market. The development of the MBS pool, which facilitates the aggregation of many thousands of unique assets into fungible securities, has been a critical factor in the growth of the MBS market to its current size. While a large portion of the MBS market has credit enhancement from government or quasi-governmental agencies, large volumes of securities are issued without such guarantees. These so-called private-label securitizations, issued without the credit support of government agencies or enterprises, typically use subordination as a mechanism for creating large amounts of triple A senior securities. The cash flows of both agency and senior private-label pass-throughs can be restructured or "tranched" to tailor securities more closely to different investors' preferences, as well as to redistribute risk and yield within the structure.

Davidson, A., Ho, T., and Lim, Y. (1994). Collateralized Mortgage Obligations: Analysis, Valuation and Portfolio Strategy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fabozzi, F. J. (ed.) (2006). The Handbook of Mortgage-Backed Securities, 6th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fabozzi, F. J., Bhattacharya, A. K., and Berliner, W. S. (2007). Mortgage-Backed Securities: Products, Structuring, and Analytical Techniques. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, F. J., and Dunlevy, J. (2001). Real Estate Backed Securities. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, F. J., and Kalotay, A. (2003). Ginnie Mae and the Secondary Mortgage Market: An Integral Part of the American Economic Engine. Government National Mortgage Association, March 2003.

Fabozzi, F. J., and Modigliani, F. (1992). Mortgage and Mortgage-Backed Securities Markets. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Fabozzi, F. J., and Ramsey, C. (1999). Collateralized Mortgage Obligations, 3rd edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, F. J., Ramsey, C., and Marz, M. (eds.) (2000). The Handbook of Nonagency Mortgage-Backed Securities. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.