GARY L. GASTINEAU

Managing Director, ETF Consultants, LLC

Abstract: Exchange-traded funds are the most popular examples of a category of financial instrument that might be characterized as a "portfolio-in-a-single-share". In addition to open-end exchange-traded funds based on the SPDR structure, closed-end funds, HOLDRs, exchange-traded notes and even FOLIOs sometimes compete in the portfolio-as-a-share market. While the products all feature multiple instruments in a single transaction, these products and structures have distinct differences in tax treatment, trading costs and convenience. The open-end exchange-traded fund structure offers unique opportunities for increased shareholder efficiency and the delivery of actively managed portfolios in a tax-efficient format. The genesis of exchange-traded funds was in portfolio or program trading and its cousin, index arbitrage.

Keywords: exchange-traded funds (ETFs), mutual funds, portfolio trading, program trading, SPDRs, HOLDRs, exchange-traded notes (ETNs), exchange of futures for physicals (EFP), TIPs, WEBS, expense ratio, closed-end funds, open-end funds, FOLIOs, creation units, arbitrageur, creation, redemption, tax efficiency, shareholder accounting, Regulated Investment Company (RIC), grantor trust, structured product, special purpose vehicle (SPV), actively managed ETFs

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are the most important—and potentially the most versatile—financial instruments introduced since the debut of financial futures a generation ago. We begin this chapter by explaining the origins of ETFs and some of their important features like intra-day trading on a stock exchange, creation and redemption of fund shares "in-kind," and tax efficiency. We also compare the recently popular open-end ETFs to competitive products like closed-end funds, conventional mutual funds, HOLDRs, exchange traded notes (ETN), and Folios in terms of costs, and applications. Advocates of conventional mutual funds, ETFs, and separate stock portfolios (including HOLDRs and Folios) have engaged in extensive discussions about the relative tax-efficiency of their respective approaches to equity portfolio management. (For a discussion of the principal tax-efficiency issues, see Gastineau [2002].)

Exchange-traded funds, referred to by friends and foes alike as "ETFs," are outstanding examples of step-by-step evolution of new financial instruments starting with a series of proto-products that led in a natural progression to the current generation of exchange-traded funds and set the stage for products yet to come. (A more detailed discussion appears in Gastineau [2001].)

The basic idea of trading an entire portfolio in a single transaction did not originate with the TIPS or SPDRS, which are the earliest successful examples of the modern portfolio-traded-as-a-share structure. The idea originated with what has come to be known as "portfolio trading" or "program trading." In the late 1970s and early 1980s, program trading was the then revolutionary ability to trade an entire portfolio, often a portfolio consisting of all the S&P 500 stocks, with a single order placed at a major brokerage firm. Some modest advances in electronic order entry technology at the NYSE and the Amex and the availability of large order desks at some major investment banking firms made these early portfolio or program trades possible. At about the same time, the introduction of S&P 500 index futures contracts at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange provided an arbitrage link between the futures contracts and the traded portfolios of stocks. It even became possible, in a trade called an exchange of futures for physicals (EFP) to exchange a stock portfolio position, long or short, for a stock index futures position, long or short. The effect of these developments was to make portfolio trading either in cash or futures markets an attractive activity for many trading desks and for many institutional investors.

As a logical consequence of these developments affecting large investors, there arose interest—one might even say insistent demand—for a readily tradable portfolio or basket product for smaller institutions and the individual investor. Before the introduction of "mini" contracts, futures contracts were relatively large in notional size. Even with "mini" contracts, the variation margin requirements for carrying a futures contract are cumbersome and relatively expensive for a small investor. Perhaps even more important, there are many more securities salespeople than futures salespeople. The need for a security—that is, an SEC-regulated portfolio product—that could be used by individual investors was apparent. An important predecessor came from Canada.

TIPs were a warehouse receipt-based instrument designed to track the TSE-35 index and a later product tracked the TSE-100 index as well. The TSE-100 product was initially called HIPs. These products traded actively and attracted substantial investment from Canadians and from international indexing investors. TIPs were unique in their expense ratio. The ability of the trustee (State Street Bank) to loan out the stock in the TIPs portfolio and frequent demand for stock loans on shares of large companies in Canada led to what was, in effect, a negative expense ratio at times.

The TIPs were a victim of their own success. They proved costly for the Exchange and for some of its members who were unable to recover their costs from investors. Early in 2000, the Toronto Stock Exchange decided to get out of the portfolio share business and TIPs positions were liquidated or rolled into a Barclays Global Investors (BGI) 60 stock index share at the option of the TIPs holder. The BGI fund was relatively low cost, but not as low cost as the TIPs, so a large fraction of the TIPs shares were liquidated.

SPDRs (pronounced "spiders"), developed by the American Stock Exchange (Amex), are the shares of a unit trust which holds an S&P 500 portfolio that, unlike the portfolios of most U.S. unit trusts, can be changed as the index changes. The reason for the selection of the unit trust structure was the Amex's concern for simplicity and costs. A mutual fund must pay the costs of a board of directors, even if the fund is very small. The Amex was uncertain of the demand for SPDRs and did not want to build a more costly infrastructure than was necessary. SPDRs traded reasonably well on the Amex in their earlier years, but only in the late 1990s did SPDRs asset growth become truly exponential. Investors began to look past the somewhat esoteric in-kind share creation and redemption process (used by market makers and large investors to acquire and redeem SPDRs in large blocks) and focused on the investment characteristics and tax efficiency of the SPDRs shares.

Today, the S&P 500 SPDRs have more assets than any other index fund except the Vanguard 500 mutual fund. The SPDRs account for less than one-sixth of ETF assets in the United States. Interestingly, however, from 70% to 90% of traditional U.S. index fund money goes into S&P 500 portfolios. Clearly, the interest in ETFs based on indexes other than the S&P 500 suggests that there is more to ETFs than an alternative to conventional index funds. (For specific analysis of the S&P 500 SPDRs see Elton, Gruber, Comer, and Li [2002].)

The WEBS, originally developed by Morgan Stanley, are important for two reasons. First, they are foreign index funds. More precisely, they are U.S.-based funds holding stocks issued by non-U.S.-based firms. Second, they are one of the earliest exchange-traded index products to use a mutual fund as opposed to a unit trust structure. The mutual fund structure has more investment flexibility and there are some other differences in dividend reinvestment and stock lending. We would expect most new funds to use the mutual fund structure.

In addition to WEBS, a variety of additional ETF products are now available. The Mid-Cap SPDRs (a unit trust run by the Bank of New York) actually came before WEBS, and the DIAMONDS (a unit trust based on the Dow Jones Index Industrial Average and run by State Street Bank) and the Nasdaq 100 (a unit trust run by the Bank of New York) were introduced later. The Select Sector SPDRs used a mutual fund structure similar to the WEBS and were introduced in late 1998.

Barclays Global Investors, a major institutional index portfolio manager, launched iShares (mutual fund type ETFs based on a large number of benchmark indexes) in a bid to develop a retail branded family of financial products. The streetTRACKS Funds (another group of mutual fund type ETFs) represent State Street's first solo ETF effort in the United States. State Street is also behind the Hong Kong TraHKers Fund and other funds for investors outside the United States. (For a slightly different perspective of the ETF landscape with more data on individual funds, see Fredman [2001a].) The fund roster continues to grow.

While most readers think of the fund products described above as ETFs, various financial instruments, each referred to by some of its advocates as an exchange-traded fund, are designed to meet specific portfolio investment needs. In many cases, the needs met are practically identical; in other cases, they are quite different. In spite of some confusion about what the term ETF includes, most observers agree that a range of exchange-traded portfolio basket products compete for investors' dollars.

Our purpose in this section is to introduce the major categories of financial instruments which sometimes have been called "ETFs" or which compete with ETFs. We will appraise the features of each. Our objective is to provide a relatively straightforward comparison of features. The purpose of the comparison is not to suggest that one structure is always superior or that the emphasis should always be on competition between the products. In fact, folio customers have been important users of the fund-type ETFs described in the previous section and of HOLDRs which are described below.

Nuveen Investments began using the term "exchange-traded funds" for its closed-end municipal bond funds traded on the New York and American Stock Exchanges in the very early 1990s, several years before the first SPDRs began trading on the American Stock Exchange. The use of the name "exchange-traded funds" was selected to emphasize the fact that someone buying and selling these municipal bond fund shares enjoyed the investor protections afforded by investment company (fund) regulation and by the auction market on a major securities exchange.

The SEC requires that references to what we have been calling exchange-traded funds as open-end funds be made only in the context of a comparison with conventional open-end investment companies (mutual funds). We are about to make such a comparison so we will drop the quotes around open, and fully qualify the limits of openness in such funds. Shares in open ETFs are issued and redeemed directly by the fund at their net asset value (NAV) only in creation unit aggregations, typically 50,000 fund shares or multiples of 50,000 shares. The shareholder who wants to buy or sell fewer than 50,000 shares may only buy and sell smaller lots on the secondary market at their current market price. The secondary market participant is dependent on competition among the exchange specialist, other market makers and arbitrageurs to keep the market price of the shares very near the intra-day value of the fund portfolio. The effectiveness of market forces in promoting tight bid asked spreads and fair pricing has been impressive. ETF shares have consistently traded very close to the value of the underlying portfolio in a contemporaneously priced market.

For the typical retail or even institutional investor, purchasing and selling ETF shares is the essence of simplicity. The trading rules and practices are those of the stock market. ETF shares are purchased and sold in the secondary market, much like stocks or shares of closed-end funds, rather than being purchased from the fund and resold to the fund, like conventional mutual fund shares.

Because they are traded like stocks, shares of ETFs can be purchased or sold any time during the trading day, unlike shares of most conventional mutual funds which are sold only at the 4:00 p.m. net asset value (NAV) as determined by the fund and applied to all orders received since the prior day's share trading deadline. While the opportunities for intra-day trading may not be important to every investor, they certainly have appeal to many investors during a period when there is concern about being able to get out of a position before the market close when prices are volatile.

Primary market transactions in ETF shares, that is, trades when shares are bought and redeemed with the fund itself as a party to the trade, consist of in-kind creations and redemptions in large size. There have been occasions when creation and redemption of fund shares has resulted in asset flows of billions of dollars in or out of the SPDR or the Nasdaq 100 Trust in a single day. Exchange specialists, market makers, and arbitrageurs buy ETF shares from the fund by depositing a stock portfolio and a cash balancing component that essentially match the fund in content and are equal in value to, say, 50,000 ETF shares on the day the fund issues the shares. The same large market participants redeem fund shares by tendering them to the fund in 50,000 share multiples and receiving a stock portfolio plus or minus balancing cash equivalent in value to the 50,000 ETF shares redeemed. The discipline of possible creation and redemption at each day's market closing NAV is a critical factor in the maintenance of fund shares at a price very, very close to the value of the fund's underlying portfolio, not just at the close of trading, but intra-day. A proxy for intra-day net asset value per share is disseminated for each ETF throughout the trading day to help investors check the reasonableness of bids and offers on the market. (This proxy value does not have the status of a formal NAV calculation.)

An extremely important feature of the creation and, more particularly, the redemption process is that redemption-in-kind does more than provide an arbitrage mechanism to assure a market price quite close to net asset value. Redemption in kind also reduces the fund's transaction costs and enhances the tax efficiency of the fund. While a conventional mutual fund can require shareholders to take a redemption payment in-kind rather than in cash for large redemptions, most funds are reluctant to do this, and most shareholders hold fund positions considerably smaller than the $250,000 minimum usually required for redemption in-kind. As a consequence, most redemptions of conventional mutual fund shares are for cash, meaning that an equity fund faced with significant shareholder redemptions is required to sell shares of portfolio stocks, frequently shares that have appreciated from their original cost. When gains taken to obtain cash for redemptions are added to gains realized on merger stocks that are removed from the index for a premium over the fund's purchase price, many conventional index funds distribute substantial capital gains to their shareholders, even though the continuing shareholders who pay taxes on these distributions have made no transactions, and the fund, looked at from a longer perspective, has been a net buyer of its index's component securities.

The in-kind redemption process for exchange-traded funds enhances tax efficiency in a simple way. The lowest cost shares of each stock in the portfolio are delivered against redemption requests. In contrast to a conventional fund which would tend to sell its highest cost stocks first, leaving it vulnerable to substantial capital gains realizations when a portfolio company is acquired at a premium and exits the index and the fund, the lowest cost lot of stock in each company in the portfolio is tendered to ETF shareholders redeeming in multiples of 50,000 fund shares. The shares of stock in each company remaining in the portfolio have a relatively higher cost basis, which means that acquired companies generate smaller or no gains when they leave the index and are sold for cash by the fund.

One further feature of the existing exchange-traded funds which causes a degree of misunderstanding and which seems to create an expectation that all ETFs will be extremely low cost funds requires an explanation. First, the existing ETFs are all index funds. Index funds generally have lower management fees than actively-managed funds, whatever their share structure. Second, ETFs enjoy somewhat lower operating costs than their conventional fund counterparts. The principal reasons for lower costs are (1) the opportunity to have a somewhat larger fund because of the popularity of the exchange-traded fund structure, (2) slightly lower transaction costs due to in-kind deposits from and payments to buyers and redeemers in the primary market and, most importantly, (3) the elimination of the transfer agency function—that is, the elimination of shareholder accounting—at the fund level.

As all U.S. ETFs are "book entry only" securities, an exchange-traded fund in the United States has one registered shareholder: the Depository Trust Company (DTC). If you want a share certificate for a SPDR or QQQ position, you are out of luck. Certificates are not available. The only certificate is held by the Depository Trust Company, and the number of shares represented by that certificate is "marked to market" for increases and decreases in shares as creations and redemptions occur.

Shareholder accounting for ETFs is maintained at the investor's brokerage firm, rather than at the fund. This creates no problems for the shareholder, although it does have some significance for the distribution of exchange-traded funds. One of the traditional functions of the mutual fund transfer agent is to keep track of the salesperson responsible for the placement of a particular fund position, so that any ongoing payments based on 12b-l fees or other marketing charges can be made to the credit of the appropriate salesperson. There is no way for the issuer of an ETF to keep track of salespeople because these fund positions do not carry the record keeping information needed to use the DTC Fund/SERV process. They are, in a word, just like shares of a stock—and a stock with no certificates at that. The elimination of the individual shareholder transfer agency function reduces operating costs by a minimum of five basis points and probably by much more in many cases. ETF expenses tend to reflect the cost savings on this function.

The trading price of an exchange-traded fund share will be subject to a bid-asked spread in the secondary market (although these are very narrow on most products) and a brokerage commission. A simple break-even analysis divides the round-trip trading costs by the daily difference in operating expenses. Anyone planning to retain a reasonably large fund position for more than a short period of time and/or anyone who values the intra-day purchase and sale features of the exchange-traded funds will find the combination of the lower expense ratio and greater flexibility make the ETF share more attractive than a conventional mutual fund share. New delivery systems developed for 401(k) accounts will reduce most small lot ETF trading costs.

Powerful advantages notwithstanding, there are a few disadvantages in the exchange-traded fund format for some investors. An investor cannot be certain of his or her ability to buy or sell shares at a price no worse than net asset value without incurring some part or all of a trading spread and a commission. (The specialized index ETFs introduced after 2004 are not enhanced index funds. The latter track a specified benchmark closely using optimization and other quantitative techniques to improve return and/or reduce risk.) It is the trading spread in the secondary market which covers the costs of insulating the ongoing shareholder from the cost of in-and-out transactions by active traders. These transaction costs in open market ETF trades mean that, even with lower fund expenses, certain small investors will not find ETFs as economical as traditional funds if they are in the habit of making periodic small investments. Since most conventional mutual funds take steps to refuse investments from in-and-out traders if they trade in and out too frequently, the transaction costs associated with ETFs are simply a more equitable allocation of these costs among various fund shareholders. A long-term investor, particularly a taxable long-term investor will benefit greatly from the exchange-traded fund structure because in the long run that investor should enjoy lower fund expenses and a higher after-tax return than he would find in an otherwise comparable conventional fund. This allocation of costs and benefits is ironic given the only significant criticism which has been leveled at exchange-traded funds, that is, that they encourage active trading. In fact, the long-term taxable investor enjoys the greatest benefits from the ETF structure. Even so, the ETF structure has probably reduced the active trader's costs as well, given the obstacles and special redemption fees these traders often incur when they use conventional funds.

As noted, all current open exchange-traded funds are index funds. As time goes by, there will be a wider variety of funds available. The introduction of enhanced index funds and ultimately actively-managed funds seems inevitable. It is in the advance from simple indexation with full replication of the index in the portfolio that the investment management company structure shows its greatest advantages over the open UIT structure because the latter structure does not provide a mechanism for anything beyond full replication of an index. The open-end management investment company structure permits a portfolio to differ from the structure of an index fairly easily if the index structure is not consistent with the diversification requirements that allow the fund to qualify as a regulated investment company (RIC) for tax purposes. The UIT structure provides for replication of an index with limited variations based on rounding share positions and limited timing adjustments of index replicating transactions by advancing or deferring them for a few days.

Alternative portfolio or basket structures differ both from the UIT and the exchange-traded investment management company. These other structures have their own unique features. Foremost among these are Holding Company Depository Receipts (HOLDRs), a structure pioneered by Merrill-Lynch, and Folios, which have been introduced by a number of firms that would otherwise be characterized primarily as deep discount brokers. Both HOLDRs and Folios are unmanaged baskets of securities which may have an initial structure based on an index, a theme, or just a diversification policy. Exchange-traded notes (ETNs) are used for assets and risk-modified positions not easily accommodated in the other structures.

HOLDRs use a grantor trust structure which makes them similar to the open ETFs discussed above in that additional HOLDRs shares can be created and existing HOLDRs can be redeemed. The creation unit aggregation for the open ETF management company structures is typically 50,000 fund shares and the minimum trading unit on the secondary market is a single fund share. In contrast, the creation unit and the minimum trading unit in HOLDRs is generally 100 shares. Most brokerage firms will not deal in fractional shares or odd lots of HOLDRs. (DTC does not transfer fractional shares or fractions of the basic trading unit of a security, which is 100 shares in the case of the HOLDRs. However, some firms use trading and accounting systems that accommodate the New York Stock Exchange's Monthly Investment Plan (MIP). MIP was designed to let investors buy odd lots and fractional shares as a start in owning their share of America. Firms which can accommodate fractional share positions (including Foliofn) see the ability to handle fractional shares as a competitive advantage.) An investor can buy and sell HOLDRs in the secondary market or an existing HOLDRs position can be redeemed (exchanged for its specific underlying stocks). A new HOLDRs position can be created by simply depositing the stocks behind the 100-share HOLDRs unit with the Bank of New York. (The stock basket underlying a 100-share HOLDRs unit will initially consist of whole shares of the component stocks. In the event of a merger affecting one of the companies, any cash proceeds will be distributed. The surviving company's whole shares will usually be retained in the HOLDRs basket.)

The creation/redemption fee for HOLDRs will generally be roughly similar in relative magnitude to the comparable fee on investment company ETFs and the pricing principles and arbitrage pricing constraints operate in a similar way. To the extent that one of the stocks in a HOLDRs basket performs poorly and the investor wants to use the loss on that stock to offset gains elsewhere, the HOLDRs can be taken apart and reassembled without affecting the tax status of any shares not sold. The ability to realize a loss on an individual position may give the HOLDRs structure a slight tax advantage over the investment company-based ETFs. On the other hand, unlike the redemption in-kind of the shares of an open ETF, the HOLDRs structure does not permit elimination of a low-cost position in the HOLDRs portfolio without realization of the gain by the investor.

The principal disadvantages of HOLDRs are that they lack the indefinite life of an investment company and there is no provision for adding positions to offset attrition through acquisitions of basket components by other companies. No HOLDRs component that disappears in a cash merger or bankruptcy can be replaced in the HOLDRs basket. If some stocks do well and others do poorly, there is no mechanism for rebalancing positions.

The HOLDRs share one very important characteristic with the index ETFs: It is frequently less costly to trade the basket in the form of HOLDRs than it is to trade the individual shares, particularly for a small- to mid-sized investor who might be trading odd lots in many of the basket components if HOLDRs or ETFs were unavailable. The grantor trust structure of HOLDRs is also used by a few securitized commodity products. The most prominent of these is the StreetTracks Gold Shares (GLD). In contrast to the HOLDRs, these commodity securitization products trade in single share units and are created and redeemed in much larger than 100-share lots.

In contrast to the other ETF variations and competitors described here, Folios are not standardized products nor are they investment companies or some kind of trust. They are baskets of stocks that can be modified one position at a time or traded with a single order through a brokerage firm. The firms which advocate and provide Folio baskets for trading do provide semi-standardized baskets—in some cases based on indexes, and in other cases based on a simple diversification rule. In practice, however, each investor's implementation of the Folio basket may be slightly different.

Because Folio baskets will not be standardized, Folios cannot be traded like fund shares or like HOLDRs. Each of the stocks in a Folio will trade separately. While the brokerage firm can provide low-cost commissions and even the opportunity to execute trades against its other customer trades at selected times during the day, if the basket does not trade as a standardized basket, the investor will miss some of the transaction cost advantages which traders in standardized basket shares often enjoy.

A tax advantage of Folios over investment companies in certain circumstances is similar to a tax feature of HOLDRs. An investor can sell one position out of a Folio to take a loss and use that loss to offset gains obtained elsewhere—outside the Folio basket. In contrast, a fund taxed as a regulated investment company cannot pass losses through to shareholders. If the fund experiences large losses, an investor can take a loss on the fund shares by selling the share position; but losses on an individual portfolio component are not available to the investor who continues to hold the shares as a passthrough. In a reasonably bullish market environment, the ability of the UIT or management company ETF to modify its portfolio with creations and redemptions without taxable gain realizations will probably be more important to an individual investor than the ability to take specific losses in either HOLDRs or Folios. Other market environments may make the selected loss realization opportunity of the HOLDRs or Folios more valuable.

In contrast to the ETFs' fund structure, there is no "tax-realization-free" mechanism for reducing the impact of a very successful position in either HOLDRs or Folios. In the regulated investment company structures (exchange-traded unit trusts or funds), tax rules would limit the size of any single stock to 25% of the assets of the fund under most circumstances. Reductions in the commitment to a particular position in a regulated investment company with redemptions in-kind might be obtainable without realization of taxable gains. This would not be possible for very successful positions underlying HOLDRs or for components of a Folio. Basket mechanisms that do not offer a way to reduce a large, successful position without capital gains realization force the investor to choose between tax deferral and diversification.

Exchange-traded notes and other structured products were introduced long before the earliest products now called ETFs were available to investors in the United States or other major markets. Some publicly traded structured products are based on special purpose vehicles (SPVs) if they require credit enhancement or separation from other entities for credit or regulatory purposes. However, most exchange-traded notes and other structured products are liabilities of major financial institutions and appear on the liability side of corporate balance sheets. The exchange-traded notes closest in structure and function to the open-end ETFs which are the primary focus of this chapter are probably the iPath notes issued by Barclays Bank PLC and marketed through its affiliate, Barclays Global Investor Services.

In contrast to the daily creation and redemption of ETFs, open-end exchange-traded notes are redeemable either weekly or monthly in most cases. The open-end note creation baskets are typically comparable in value to ETF creation or redemption baskets. Depending on the nature of the note and the underlying index portfolio or commodity exposure it provides, an ETN may pay an interest-like payment or be marked to market daily and purchased and sold on the basis of its net asset value. While the expiration dates of exchange-traded notes may be distant, a maturity date more than 30 years in the future is very rare. Not all ETNs have explicit management fees or expenses analogous to the expenses of an exchange-traded fund. Consequently, understanding the economics of an ETN can be a complex exercise. The flexibility of ETN and structured products formats has made these instruments increasingly popular with many investors.

The relatively recent introduction and popularity of open-end ETNs suggests opportunities for considerable growth. The principal constraint on growth is that, in contrast to a fund or a grantor trust where the underlying portfolio is held for the benefit of investors, the value of ETNs and most other structured products is highly dependent on the credit of the issuer. While lower rated financial service firms frequently "rent" the balance sheets of more highly rated firms to issue structured products, credit evaluation is always a significant consideration in any decision to use ETNs or other structured products.

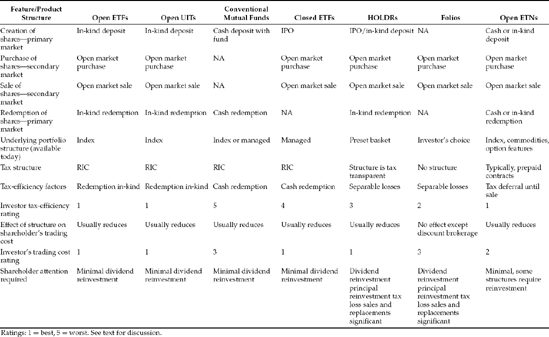

Table 61.1 provides an eclectic comparison of the mutual fund-style and UIT-style versions of open exchange-traded funds and conventional mutual funds to the other basket products we have discussed. Most of the items on this comparison table are relatively straightforward and readily understandable from the previous text, but several items do require some discussion. (For a slightly different but useful perspective, see Fredman [2001b].)

In assigning tax-efficiency ratings, we have placed significantly greater value on the redemption in-kind feature of the open ETFs and open UITs than on the separable loss feature available in Folios with no particular change and in HOLDRs through the exchange of the HOLDR for the basket of underlying securities followed by realization of the loss, reestablishment of the position that incurred the loss after the wash sale period is past and reconstitution of the HOLDR—a relatively complex and non-user-friendly process. Open ETNs vary in tax efficiency, but most provide substantial tax deferral.

Closed-end funds are rated higher than conventional mutual funds on tax efficiency because they are characterized by a closed portfolio and do not face the forced realization of gains which can come about through cash redemptions in an open-end mutual fund.

The investor's trading cost ratings are based largely on the advantages associated with trading a basket at the share level versus transacting separately in all the securities making up the basket. All of the standardized ETFs are ranked highly because trading in the composite share should be more efficient than trading in the underlying positions separately. It is certainly possible to differentiate among individual products in terms of the cost of trading the product or trading the underlying securities separately, but the difference is more related to the nature of the underlying market and the quality of the market in the basket product than it is on anything systematically related to the product structure. The assets underlying most ETNs are more costly to trade than the average ETF basket. The conventional mutual funds are rated slightly below the exchange-traded products other than the unstructured Folios on the assumption that, on average, a redemption charge or other obstacles to short-term trading will increase an investor's costs of trading. (An investor can do an in-and-out trade in some conventional mutual funds with almost no transaction cost, but many funds will probably not accept a repeat order from that investor.) In any event, the free liquidity mutual funds offer traders is an ongoing trading cost borne by all mutual fund investors. Folios are rated less favorably on trading cost simply because they do not provide any of the advantages associated with trading the other products as portfolios or baskets. Even when the transactions in a Folio are aggregated, each stock is traded separately. None of the Folio providers have reached a size that permits them to match and offset many customer orders to eliminate the bid-asked spread.

HOLDRs and Folios require somewhat greater investor (or manager) attention than the conventional fund or exchange-traded fund products for at least two reasons: First, to the extent that any of the companies in the HOLDRs or Folios are taken over in a cash acquisition, the shares will automatically be turned into cash and the shareholder will have to deal with reinvestment of the principal. Also, both these less structured products provide for their variety of tax-efficiency by permitting tax loss sales of individual securities. Folios, which are marketed principally as a way to take advantage of the automatic diversification a portfolio of stocks provides, require some kind of replacement or re-balancing activity to maintain a useful degree of diversification. With the other products, either a portfolio manager or the process for weighting or re-weighting the index and insuring regulated investment company diversification compliance in the fund will retain a minimal level of diversification without action by the investor or an advisor employed to manage the investor's position.

It is appropriate to look at some new ETF features that will improve the performance of these funds for investors. If any fund is going to serve the interest of its shareholders, the portfolio manager needs to implement portfolio changes without revealing the fund's ongoing trading plans. Whether a fund is attempting to replicate an index or to follow an active portfolio selection or allocation process, portfolio composition changes cannot be made efficiently if the market knows what changes a fund will make in its portfolio before the fund completes its trades. A number of recent studies have highlighted an index composition change problem which many of indexing's strong supporters have been aware of for some time: Benchmark indexes like the S&P 500 and the Russell 2000 do not make efficient portfolio templates. Investors in index funds based on popular, transparent indexes are dis-advantaged by the fact that anyone who cares will know what changes the fund must make before the fund's portfolio manager can make them. When transparency means that someone can earn an arbitrage profit by frontrunning a fund's trades, transparency is not desirable.

The cost to ongoing shareholders of preannounced portfolio composition changes in index ETFs must be eliminated. The best way to improve index fund performance is to use silent indexes—indexes that keep portfolio composition changes confidential until after the fund has traded. This requires radically new procedures for the management of indexes and for the management of index funds.

Everyone seems to agree that actively managed funds require confidential treatment of portfolio composition changes until after the fund has traded. Only recently have investors begun to understand the costs that index transparency imposes on index fund investors. Making portfolio changes confidential and efficient requires changes in the ETF structure and the portfolio trading process.

Many individual investors have a stake in being able to make small, periodic purchases or sales in their fund share accounts. The prototypical investor of this type is the 401(k) investor who invests a small amount in his defined contribution retirement plan every payroll period. The mutual fund industry has developed an elaborate framework which permits small orders for a large number of investors to be aggregated and for cash to enter or leave the fund to accommodate small investors at net asset value. There are ways to modify ETF procedures so that these investors, while paying a little more than they have paid in the past to cover the transaction costs of their entry and exit, will still be accommodated at low cost. The snowballing rush to greater transparency in the economics of defined contribution accounts like 401(k) plans will make fund cost and performance comparisons easier—to the advantage of ETFs. The only "problem" that limits the ability of ETFs to deliver this degree of shareholder protection is that the true transaction costs associated with buying and selling shares of an ETF can be difficult for an investor to determine in advance of trading.

One solution to this problem is a new trading process that increases the transparency of ETF transaction costs and, consequently, improves the ETF structural shareholder protection without compromising the ETF "gold" standard whereby investors entering and leaving the fund pay the costs of their entry and exit. In most discussions of actively managed ETFs, there has been appropriate concern expressed for the cost of achieving enough portfolio transparency to facilitate trading in ETFs without subjecting the fund's trades to the front running risk that all of today's index funds experience. The SEC's Concept Release on actively managed ETFs stressed the importance of finding a solution to this problem. It is now apparent that the manager of an actively managed ETF needs to offer no more information on his portfolio composition and portfolio changes than the manager of a conventional mutual fund must publish today. Funds that do not require the full measure of confidentiality available under today's rules for fund asset disclosure can reduce transaction costs for their entering and leaving shareholders and for market makers by providing more frequent disclosure. But more frequent disclosure is not essential. An investment process that requires the maximum permitted portfolio confidentiality can work well inside an actively-managed ETF.

Fund issuers can build on the compelling advantages of exchange-traded funds to offer better and more varied portfolios. New actively managed and improved index funds can offer their shareholders full protection from the cost of entry and exit by other fund shareholders and the tax efficiency that are inherent in the initial generation of SPDR-style exchange-traded funds.

This chapter describes the relatively short history of exchange-traded funds and their principal competitors. It provides an analysis of the various products and their investment, tax, legal and structural characteristics. The version of the exchange-traded fund that is based on the investment company structure (which it uses in common with conventional mutual funds) shows great promise for active management in competition with mutual funds.

Elton, E. J., Gruber, M. J., Comer, G., and Li, K. (2002). Where are the bugs? Journal of Business, June: 453-472.

Fredman, A. J. (2001a). An investor's guide to analyzing exchange-traded funds. AAII Journal, May: 8-13.

Fredman, A. J. (2001b). Sizing up mutual fund relatives: low-cost alternative investing. AAII Journal, July: 9-14.

Gastineau, G. L. (2001a). Exchange-traded funds—An introduction. Journal of Portfolio Management, Spring: 88-96.

Gastineau, G. L. (2001b). Silence is golden: The importance of stealth in pursuit of the perfect fund index. Journal of Indexes, Second Quarter: 8-13.

Gastineau, G. L. (2002). The Exchange-Traded Funds Manual. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Gastineau, G. L. (2003). Converting actively-managed mutual funds to ETFs. Unpublished manuscript, ETF Consultants LLC.

Gastineau, G. L. (2004a). Single stock futures on exchange-traded funds. Futures, January: 38-41.

Gastineau, G. L. (2004b). Protecting fund shareholders from costly share trading. Financial Analysts Journal, May/June: 22-32.

Gastineau, G. L. (2004c). An exchange-traded fund or conventional fund—You can't really have it both ways. Journal of Indexes, First Quarter: 32-34.

Gastineau, G. L. (2005). The anatomy of tax efficiency. Journal of Indexes, May-June: 12-15.

Lazzara, C. J. (2003). Index construction issues for exchange-traded funds. Unpublished manuscript, ETF Consultants LLC.