MARK J.P. ANSON, PhD, JD, CPA, CFA, CAIA

President and Executive Director of Nuveen Investment Services

Abstract: The private equity sector purchases the private stock or equity-linked securities of nonpublic companies that are expected to go public or provides the capital for public companies (or their divisions) that may wish to go private. The key component in either case is the private nature of the securities purchased. Private equity by definition, is not publicly traded. Therefore, investments in private equity are illiquid. Investors in this marketplace must be prepared to invest for the long haul—investment horizons may be as long as 5 to 10 years. Private equity is a generic term that encompasses four distinct strategies in the market for private investing. First, there is venture capital, the financing of start-up companies. Second, there are leveraged buyouts (LBOs) where public companies repurchase all of their outstanding shares and turn themselves into private companies. Third, there is mezzanine financing, a hybrid of private debt and equity financing. Finally, there is distressed debt investing. These are private equity investments in established (as opposed to start-up) but troubled companies.

Keywords: venture capitalist, limited partnership, limited liability company, investment restrictions, management fees, profit sharing, business plan, intellectual property, management team, exit plan, J curve, angel investor, seed capital, early stage, late stage, mezzanine stage, initial public offering

Private equity is as old as Columbus's journey to America. Queen Isabella of Spain sold her jewelry to finance Columbus's small fleet of ships in return for whatever spoils Columbus could find in the New World. The risks were great, but the potential rewards were even greater. This in a nutshell summarizes the private equity market: a large risk of failure but the potential for outstanding gains.

More generally private equity provides the long-term equity base of a company that is not listed on any exchange and therefore cannot raise capital via the public stock market. Private equity provides the working capital that is used to help private companies grow and succeed. It is a long-term investment process that requires patient due diligence and hands-on monitoring.

In this chapter, we focus on the best known of the private equity categories: venture capital. Venture capital is the supply of equity financing to start-up companies that do not have a sufficient track record to attract investment capital from traditional sources (e.g., the public markets or lending institutions). Entrepreneurs that develop business plans require investment capital to implement those plans. However, these start-up ventures often lack tangible assets that can be used as collateral for a loan. In addition, start-up companies are unlikely to produce positive earnings for several years. Negative cash flows are another reason why banks and other lending institutions as well as the public stock market are unwilling to provide capital to support the business plan.

It is in this uncertain space where nascent companies are born that venture capitalists operate. Venture capitalists finance these high-risk, illiquid, and unproven ideas by purchasing senior equity stakes while the firms are still privately held. The ultimate goal is to make a buck. Venture capitalists are willing to underwrite new ventures with untested products and bear the risk of no liquidity only if they can expect a reasonable return for their efforts. Often, venture capitalists set expected target rates of return of 33% or more to support the risks they bear. Successful start-up companies funded by venture capital money include Cisco Systems, Cray Research, Microsoft, and Genentech.

We begin with the role of a venture capitalist in a start-up company raising a venture capital fund. Next, we review the heart of the venture capital industry—the business plan. We then review the current structure of the industry. This is followed by a review of the different stages of venture capital financing.

Venture capitalists have two roles within the industry. Raising money from investors is just the first part. The second is to invest that capital with start-up companies.

Venture capitalists are not passive investors. Once they invest in a company, they take an active role either in an advisory capacity or as a director on the board of the company. They monitor the progress of the company, implement incentive plans for the entrepreneurs and management, and establish financial goals for the company.

Besides providing management insight, venture capitalists usually have the right to hire and fire key managers, including the original entrepreneur. They also provide access to consultants, accountants, lawyers, investment bankers, and most importantly, other business that might purchase the start-up company's product.

In this section we focus on the relationship between the venture capitalist and his investors. In the next section we consider the process by which a venture capitalist selects investments.

Before a venture capitalist can invest money with startup ventures, she must go through a period of fund raising with outside investors. Most venture capital funds are structured as limited partnerships, where the venture capitalist is the general partner and the investors are limited partners. Each venture capital fund first goes through a period of fund raising before it begins to invest the capital raised from the limited partners.

The venture capitalist, or her company, is the general partner of the venture capital fund. All other investors are limited partners. As the general partner, the venture capitalist has full operating authority to manage the fund as she pleases, subject to restrictions placed in the covenants of the fund's documents.

As the venture capital industry grew and matured through the 1980s and 1990s, sophisticated investors such as pension funds, endowments, foundations, and high-net-worth individuals began to demand that contractual provisions be placed in the documents and subscription agreements that establish and govern a private equity fund. These covenants ensure that the venture capitalist sticks to her knitting and operates in the best interest of the limited partners who have invested in the venture capital fund.

These protective covenants can be broken down into three broad classes of investor protections: (1) covenants relating to the overall management of the fund; (2) covenants that relate to the activities of the general partners; and (3) covenants that determine what constitutes a permissible investment (see Lerner, 2000).

Typically the most important covenant is the size of an investment by the venture capital fund in any one startup venture. This is typically expressed as a percentage of the capital committed to the venture capital fund. The purpose is to ensure that the venture capitalist does not bet the fund on any single investment. In any venture capital fund, there will be start-up ventures that fail to generate a return. This is expected. By diversifying across several venture investments, this risk is mitigated.

Other covenants may include a restriction on the use of debt or leverage by the venture capitalist. Venture capital investments are risky enough without the venture capitalist's gearing up the fund through borrowing.

In addition, there may be a restriction on coin vestments with prior or future funds controlled by the venture capitalist. If a venture capitalist has made a poor investment in a prior fund, the investors in the current fund do not want the venture capitalist to throw more good money after bad. Last, there is usually a covenant regarding the distribution of profits. It is optimal for investors to receive the profits as they accrue. Furthermore, distributed profits reduce the amount of committed capital in the venture fund, which in turn reduces the fees paid to the venture capitalist. It is in the venture capitalist's economic interest to hold onto profits, while investors prefer to have them distributed as they accrue.

Primary among these is a limit on the amount of private investments the venture capitalist can make in any of the firms funded by the venture capital fund. If the venture capitalist makes private investments on her own in a select group of companies, these companies may receive more attention than the remaining portfolio of companies contained in the venture fund.

In addition, general partners are often limited in their ability to sell their general partnership interest in the venture fund to a third party. Such a sale would likely reduce the general partner's incentive to monitor and produce an effective exit strategy for the venture fund's portfolio companies.

Two other covenants are related to keeping the venture capitalist's eye on the ball. The first is a restriction on the amount of future fund raising. Fund raising is time consuming and distracting—less time is spent managing the investments of the fund. Also, the limited partners typically demand that the general partner spend substantially all of his time on managing the investments of the fund— outside interests are limited or restricted.

Generally these covenants serve to keep the venture capitalist focused on investing in those companies, industries, and transactions where she has the greatest experience. So, for instance, there may be restrictions or prohibitions on investing in leveraged buyouts, other venture capital funds, foreign securities, or companies and industries outside the realm of the venture capitalist's expertise.

Venture capitalists earn fees two ways: management fees and a percentage of the profits earned by the venture fund. Management fees can range anywhere from 1% to 3.5%, with most venture capital funds in the 2% to 2.5% range. Management fees are used to compensate the venture capitalist while she looks for attractive investment opportunities for the venture fund.

A key point is that the management fee is assessed on the amount of committed capital, not invested capital. Consider the following example: The venture capitalist raises $100 million in committed capital for her venture fund. The management fee is 2.5%. To date, only $50 million dollars of the raised capital has been invested. The annual management fee that the venture capitalist collects is $2.5 million—2.5% × $100 million—even though not all of the capital has been invested. Investors pay the management fee on the amount of capital they have agreed to commit to the venture fund whether or not that capital has actually been invested.

Consider the implications of this fee arrangement. The venture capitalist collects a management fee from the moment that an investor signs a subscription agreement to invest capital in the venture fund—even though no capital has actually been contributed by the limited partners yet. Furthermore, the venture capitalist then has a call option to demand—according to the subscription agreement—that the investors contribute capital when the venture capitalist finds an appropriate investment for the fund. This is a great deal for the venture capitalist—she is paid a large fee to have a call option on the limited partners' capital. Not a bad business model. We will see later that this has some keen implications for leveraged buyout funds.

The second part of the remuneration for a venture capitalist is the profit-sharing or incentive fees. This is really where the venture capitalist makes her money. Incentive fees provide the venture capitalist with a share of the profits generated by the venture fund. The typical incentive fee is 20%, but the better-known venture capital funds can charge up to 35%. That is, the best venture capitalists can claim one-third of the profits generated by the venture fund.

The incentive fees for venture capital funds are a free option. If the venture capitalist generates profits for the venture fund, she can collect a share of these profits. If the venture fund loses money, the venture capitalist does not collect an incentive fee. This option has significant value to the venture capitalist. Furthermore, valued within an option context, venture capital profit-sharing fees provide some interesting incentives to the venture capitalist.

For example, one way to increase the value of a call option is to increase the volatility of the underlying asset. This means that the venture capitalist is encouraged to make riskier investments with the pool of capital in the venture fund to maximize the value of his incentive fee. This increased risk may run counter to the desires of the limited partners to maintain a less risky profile. It is also fascinating to realize that this incentive fee is costless to the venture capitalist—she does not pay any price for the receipt of this option. Indeed, the venture capitalist gets paid a management fee in addition to this free call option on the profits of the venture fund. As we noted previously, this is not a bad business model for the venture capitalist.

Fortunately, there is a check and balance on incentive fees in the venture capital world. Most, if not all, venture capital limited partnership agreements include some restrictive covenants on when incentive fees may be paid to the venture capitalist. There are three primary covenants that are used.

First, most venture capital partnership agreements include a clawback provision. A clawback covenant allows the limited partners to clawback previously paid incentive fees to the venture capitalist if, at the end/liquidation of the venture fund, the limited partners are still out of pocket some costs or lost capital investment. This prevents the venture capitalist from making money if the limited partners do not earn a profit.

Second, there is often an escrow agreement where a portion of the venture capitalist incentive fees are held in a segregated escrow account until the fund is liquidated.

Again this ensures that the venture capitalist does not walk away with any profit unless the limited partners also earn a profit. If a profit is earned by every limited partner, the escrow proceeds are released to the venture capitalist.

Finally, there is often a prohibition on the distribution of profit-sharing fees to the venture capitalist until all committed capital is paid back to the limited partners. In other words, the limited partners must first be paid back their invested capital before profits may be shared in the venture fund. Sometimes this covenant also includes that all management fees must be recouped by the limited partners before the venture capitalist can collect his incentive fees.

Just as a side observation, it is interesting to note that these types of profit-sharing covenants are not used in hedge fund limited partnership agreements.

The venture capitalist has two constituencies: investors on the one hand, and start-up portfolio companies on the other. In the prior section we discussed the relationship between the venture capitalist and her investors. In this section we discuss how a venture capitalist selects her investments for the venture fund.

The most important document upon which a venture capitalist will base her decision to invest in a start-up company is the business plan. The business plan must be comprehensive, coherent, and internally consistent. It must clearly state the business strategy, identify the niche that the new company will fill, and describe the resources needed to fill that niche.

The business plan also reflects the start-up management team's ability to develop and present an intelligent and strategic plan of action. The business plan not only describes the business opportunity but also gives the venture capitalist an insight to the viability of the management team.

Last, the business plan must be realistic. One part of every business plan is the assumptions about revenue growth, cash-burn rate, additional rounds of capital injection, and expected date of profitability and/or initial public offering (IPO) status. The financial goals stated in the business plan must be achievable. Additionally financial milestones identified in the business plan can become important conditions for the vesting of management equity, the release of deferred investment commitments, and the control of the board of directors.

In this section we review the key elements of a business plan for a start-up venture. This is the heart and soul of the venture capital industry—it is where new ideas are born and capital is committed.

The executive summary is the opening statement of any business plan. In this short synopsis, it must be clear what is the unique selling point of the start-up venture. Is it a new product, distribution channel, manufacturing process, chip design, or consumer service? Whatever it is, it must be spelled out clearly for a nontechnical person to understand (see the British Venture Capital Association, 2004).

The executive summary should quickly summarize the eight main parts of the business plan:

The market

The product/service

Intellectual property rights

The management team

Operations and prior operating history

Financial projections

Amount of financing

Exit opportunities

We next discuss briefly each part of the business plan.

The key issue here is whether there is a viable commercial opportunity for the start-up venture. The first question is whether there is an existing market already. If the answer is yes, this is both good and bad. It is good because the commercial opportunity has already been demonstrated by someone else. It is bad because someone else has already developed a product or service to meet the existing demand.

This raises the issue of competition. Virtually every new product already has some competition at the outset. It is most unlikely that the product or service is so revolutionary that there is no form of competition. Even if the start-up venture is first to market, there must be an explanation on how this gap in the market is currently being filled with existing (but deficient) solutions.

An existing product makes a prima facie case for market demand, but then the start-up venture must describe how its product/service improves upon the existing market solution. Furthermore, if there is an existing product, the start-up venture should make a direct product comparison including price, quality, length of warranty, ease of use, product distribution, and target audience.

In addition to a review of the competition, the start-up venture must describe its market plan. The marketing plan must include three elements: pricing, product distribution, and promotion.

Pricing is clear enough. If the product is first to market, it can command a price premium. Furthermore, in today's electronic markets, prices erode rapidly. The start-up venture must describe its initial margins, but also how those margins will be affected as technology advances are made.

Product distribution is simply a way to describe how the start-up venture will get its product to the market. Will it use wholesalers, retailers, the Internet, or direct sales? Is a sales force needed? Is a 24-hour help desk required? Also, different distribution channels may require different pricing. For example, wholesalers will need price discounts to be able to make a profit when they sell to retailers. Conversely, the start-up company may wish to offer a discount to those that order the product directly from the start-up venture.

Finally, the start-up venture must describe its promotion strategy. A discussion of trade shows, the Internet, mass media, and tie-ins to other products should be described. The start-up venture should indicate whether its product should be marketed to a targeted audience or whether it has mass appeal. The cost of promotional materials and events must also be evaluated as part of the business plan.

A description of the product or service should be done along every dimension that establishes the start-up venture's unique selling point. Furthermore, this discussion must be done in plain English without the psychobabble or jargon that normally creeps into the explanation of technology products.

In fact, the key part of this section of the business plan is to cement the unique selling point of the product or service. Is it new to the market, available at a lower price, constructed with better quality, constructed in a shorter time frame, provided with better customer service, smaller in size, easier to operate, and so on? Each of these points can provide a competitive advantage on which to build a new product or service.

One-shot, single products are a concern for a venture capitalist. The upside will be inevitably limited as competition is drawn into the market. Therefore, business plans that address a second generation of products are generally preferred.

The third essential part of the business plan is a discussion of intellectual property rights. Most of the industries where venture capital has flowed in recent years are technology related, such as computer software, telecom, biotech, and semiconductors.

Most start-ups in the technology and other growth sectors base their business opportunity on the claim to proprietary technology. It is very important that a start-up's claim and rights to that intellectual property be absolute. Any intellectual property owned by the company must be clearly and unequivocally assigned to the company by third parties (usually the entrepreneur and management team). A structure where the entrepreneur still owns the intellectual property but licenses it to the start-up company are disfavored by venture capitalists because license agreements can expire or be terminated, leaving the venture capitalist with a shell of a start-up company.

Generally, before a venture capitalist invests with a start-up company, it will conduct patent and trademark searches, seek the opinion of a patent counsel, and possibly ask third parties to confidentially evaluate the technology owned by the start-up company.

Additionally, the venture capitalist may ask key employees to sign noncompetition agreements, where they agree not to start another company or join another company operating in the same sector as the start-up for a reasonable period of time. Key employees may also be asked to sign nondisclosure agreements because protecting a start-up company's proprietary technology is an essential element to success.

Venture capitalists invest in ideas and people. Once the venture capitalist has reviewed the start-up venture's unique selling point, she will turn to the management team. Ideally, the management team should have complementary skill sets: marketing, technology, finance, and operations. Every management team has gaps. The business plan must carefully address how these gaps will be filled.

The venture capitalist will closely review the resumes of every member of the management team. Academic backgrounds, professional work history, and references will all be checked. Most important to the venture capitalist will be the professional background of the management team. In particular, a management team that has successfully brought a previous start-up company to the IPO stage will be viewed most favorably.

In general, a great management team with a good business plan is viewed more favorably than a good management team with a great business plan. The best business plan in the world can still fail from inability to execute. Thus, a management team that has demonstrated a previous ability to follow and execute a business plan gets a greater chance of success than an unproven management team with a great business opportunity.

However, this is where a venture capitalist can add value. Recognizing a great business opportunity but a weak management team, the venture capitalist can bring his or her expertise to the start-up company as well as bring in other, more seasoned management professionals. While this often creates some friction with the original entrepreneur, the ultimate goal is to make money. Egos often succumb when there is money to be made.

In addition to filling in the gaps of the management team, the venture capitalist will need to round out the board of directors of the start-up venture. One seat on the board will be filled by a member of the venture capitalist's own team. However, other directors may be added to fill in some of the gaps found among the management team. These gaps might include distribution expertise. In addition, the venture capitalist may ask an executive from an established company to sit on the board of the start-up to provide contacts within the industry when the start-up is ready to look for a strategic buyer. In addition, a seasoned board member from a successful company can lend credibility to a start-up venture when it decides to go public (see case study on CacheFlow/Blue Coat in Anson [2006]).

Last, the management team will need a seasoned chief financial officer (CFO). This will be the person primarily responsible for bringing the start-up company public. The CFO will work with the investment bankers to establish the price of the company's stock at the IPO. Since the IPO is often the exit strategy for the venture capitalist as well as some of the founders and key employees, it is critical that the CFO have IPO experience.

The operations section of the business plan discusses how the product will be built or the service delivered. This will include a discussion of production facilities, labor requirements, raw materials, tax incentives, regulatory approvals, and shipping.

In addition, if a prototype has not yet been developed, then the business plan must lay out a timeline for its production as well as its cost. Cost of production must be discussed because this will feed into the gross margin discussion as part of the financial projections (discussed next).

Last, barriers to entry should be described. While there might be a higher cost of production at the outset, it will also prevent competition from entering the market later.

Venture capitalists are not always the first investors in a start-up company. In fact, they may be the third source of financing for a company. Many start-up companies begin by seeking capital from friends, family members, and business associates. Next, they may seek a so-called "angel investor": a wealthy private individual or an institution that invests capital with the company but does not take an active role in managing or directing the strategy of the company. Then come the venture capitalists.

As a result, a start-up company may already have a prior history before presenting its business plan to a venture capitalist. At this stage, venture capitalists ensure that the start-up company does not have any unusual history such as a prior bankruptcy or failure.

The venture capitalist will also closely review the equity stakes that have been previously provided to family, friends, business associates, and angel investors. These equity stakes should be clearly identified in the business plan and any unusual provisions must be discussed. Equity interests can include common stock, preferred stock, convertible securities, rights, warrants, and stock options. There must still be sufficient equity and upside potential for the venture capitalist to invest. Finally, all prior security issues must be properly documented and must comply with applicable securities laws.

The venture capitalist will also check the company's articles of incorporation to determine whether it is in good legal standing in the state of incorporation. Furthermore, the venture capitalist will examine the company's bylaws, and the minutes of any shareholder and board of directors meetings. The minutes of the meetings can indicate whether the company has a clear sense of direction or whether it is mired in indecision.

In light of the discussion on operations and cost of projections, this information leads right into the financial projections. A comprehensive set of financial statements are required including income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow projections. These projections must be realistic but at the same time, entice the venture capitalist that there is a sufficient return to be earned to warrant the investment of capital.

First, the income statement must show in which year a breakeven point will be achieved. Most business plans show a profit being turned by the third year after initial financing. The income statement should include realistic sales forecasts, allowances for discounts, clear numbers for the cost of goods sold, and reasonable estimates of marketing and other overhead costs. Gross margins and net margins must meet the return requirements of the venture capitalist.

The balance sheet is important to determine at what point debt and other forms of financing should be added to the capital structure of the start-up venture. Also, the balance sheet should reflect the receivables received from the sale of the product as well as reasonable assumptions about the timing and collection of those receivables.

Finally, the cash flow statement provides the venture capitalist with a realistic burn rate on the cash on hand. Initially, all firms require infusions of capital to fund their working capital. However, at some point in time, the start-up venture must become self-financing such that its operating and expansion needs can draw from the money raised from the sale of its products.

For all of these financial projections, different scenarios must be included. What happens if a new competitor comes to the market quickly or the economy experiences a period of recessionary growth? Generally, the forecasts should include a base case of sales growth, a pessimistic case, and an optimistic case.

This section of the business plan gets down to brass tacks: how much money is the start-up venture requesting? This ties in neatly from the financial projections. As part of the assessment of cash flows, the start-up company needs to estimate its burn rate. The burn rate is simply the rate at which the start-up venture uses cash on a monthly basis. The amount of financing requested must be equal to the burn rate over the time horizon expected by the start-up venture.

Eventually, the venture capitalist must liquidate her investment in the start-up company to realize a gain for herself and her investors. When a venture capitalist reviews a business plan, she will keep in mind the timing and probability of an exit strategy.

An exit strategy is another way the venture capitalist can add value beyond providing start-up financing. Venture capitalists often have many contacts with established operating companies. An established company may be willing to acquire the start-up company for its technology as part of a strategic expansion of its product line. Alternatively venture capitalists maintain close ties with investment bankers. These bankers will be necessary if the startup company decides to seek an IPO. In addition, a venture capitalist may ask other venture capitalists to invest in the start-up company. This helps to spread the risk as well as provide additional sources of contacts with operating companies and investment bankers.

Venture capitalists almost always invest in the convertible preferred stock of the start-up company. There may be several rounds (or series) of financing of preferred stock before a start-up company goes public. Convertible preferred shares are the accepted manner of investment because these shares carry a priority over common stock in terms of dividends, voting rights, and liquidation preferences. Furthermore, venture capitalists have the option to convert their shares to common stock to enjoy the benefits of an IPO.

Other investment structures used by venture capitalists include convertible notes or debentures that provide for the conversion of the principal amount of the note or bond into either common or preferred shares at the option of the venture capitalist. Convertible notes and debentures may also be converted upon the occurrence of an event such as a merger, acquisition, or IPO. Venture capitalists may also be granted warrants to purchase the common equity of the start-up company as well as stock rights in the event of an IPO.

Other exit strategies used by venture capitalists are redemption rights and put options. Usually, these strategies are used as part of a company reorganization. Redemption rights and put options are generally not favored because they do not provide as large a rate of return as an acquisition or IPO. These strategies are often used as a last resort when there are no other viable alternatives. Redemption rights and put options are usually negotiated at the time the venture capitalist makes an investment in the start-up company (often called the registration rights agreement).

Usually, venture capitalists require no less than the minimum return provided for in the liquidation preference of a preferred stock investment. Alternatively, the redemption rights or put option might be established by a common stock equivalent value that is usually determined by an investment banking appraisal. Last redemption rights or put option values may be based on a multiple of sales or earnings. Some redemption rights take the highest of all three valuation methods: the liquidation preference, the appraisal value, or the earnings/sales multiple.

In sum, there are many issues a venture capitalist must sort through before funding a start-up company. These issues range from identifying the business opportunity to sorting through legal and regulatory issues. Along the way, the venture capital must assess the quality of the management team, prior capital infusions, status of proprietary technology, operating history (if any) of the company, and timing and likelihood of an exit strategy.

The structure of the venture capital industry has changed dramatically over the past 20 years. We focus on three major changes: sources of venture capital financing, venture capital investment vehicles, and specialization within the industry

The structure of the venture capital marketplace has changed considerably since 1985. What is most notable is the leading sources of venture capital financing. For example, over the period 1985 to 1990, the leading source of venture capital financing was pension funds. This came as a result of the revisions to the prudent person standard for pension fund investing in 1979. Over the 1985 to 1990 period, pension funds accounted for almost 70% of venture capital funding. Endowments and intermediaries, on the other hand, were a smaller source of venture capital funds. Also, in 1985 to 1990, government agencies accounted for about 11% of the total source of venture capital funds (see Lipin, 2000).

By 2005, the landscape of venture capital financing had changed considerably. Pension funds account for only about 50% of the source of venture capital funds. Government agencies supplied almost no money to venture capital in 2005, squeezed out by private sources. The federal and state governments no longer need to support the venture capital industry. Virtually all money comes from institutional and other investors willing to take the risk of start-up companies in return for sizeable gains.

To replace the decline of pension funds and government agencies, three new sources of venture capital funds have grown over the last 15 years: endowments and foundations, intermediaries, and individuals. Endowments, with their perpetual investment horizons, are natural investors for private equity. Also, as the wealth of the United States has grown, wealthy individuals have allocated a greater share of their wealth to venture capital investments. Finally, intermediaries such as private equity fund of funds, hedge funds, crossover funds, and interval funds have entered the venture capital market.

As the interest for venture capital investments has increased, venture capitalists have responded with new vehicles for venture financing. These include limited partnerships, limited liability companies, corporate venture funds, and venture capital fund of funds.

Limited Partnerships

The predominant form of venture capital investing in the United States is the limited partnership. Venture capitalists operate either as "3(c)(1)" or "3(c)(7)" funds to avoid registration as an investment company under the Investment Company Act of 1940. As a limited partnership, all income and capital gains flow through the partnership to the limited partner investors. The partnership itself is not taxed. The appeal of the limited partnership vehicle has increased since 1996 with the "check the box" provision of the U.S. tax code.

Previously limited partnerships had to meet several tests to determine if their predominant operating characteristics resembled more a partnership than a corporation. Such characteristics included, for instance, a limited term of existence. Failure to qualify as a limited partnership would mean double taxation for the investment fund— first, at the fund level, and second, at the investor level.

This changed with the U.S. Internal Revenue Service's decision to let entities simply decide their own tax status by checking a box on their annual tax form as to whether they wished to be taxed as a corporation or as a partnership. "Checking the box" greatly encouraged investment funds to establish themselves as a limited partnership.

Limited partnerships are generally formed with an expected life of 10 years with an option to extend the limited partnership for another 1 to 5 years. The limited partnership is managed by a general partner who has day-to-day responsibility for managing the venture capital fund's investments as well as general liability for any lawsuits that may be brought against the fund. Limited partners, as their name implies, have only a limited (investor) role in the partnership. They do not partake in the management of the fund, and they do not bear any liability beyond their committed capital.

All partners in the fund will commit to a specific investment amount at the formation of the limited partnership. However, the limited partners do not contribute money to the fund until it is called down or "taken down" by the general partner. Usually, the general partner will give one to two months' notice of when it intends to make additional capital calls on the limited partners. Capital calls are made when the general partner has found a start-up company in which to invest. The general partner can make capital calls up to the amount of the limited partners' initial commitments.

An important element of limited partnership venture funds is that the general partner/venture capitalist has also committed investment capital to the fund. This assures the limited partners of an alignment of interests with the venture capitalist. Typically, limited partnership agreements specify a percentage or dollar amount of capital that the general partner must commit to the partnership.

Limited Liability Companies

Another financing vehicle in the venture capital industry is the limited liability company (LLC). Similar to a limited partnership, all items of net income or loss as well as capital gains are passed through to the shareholders in the LLC.

Also, like a limited partnership, an LLC must adhere to the safe harbors of the Investment Company Act of 1940. In addition, LLCs usually have a life of 10 years with possible options to extend for another 1 to 5 years.

The managing director of an LLC acts like the general partner of a limited partnership. She has management responsibility for the LLC including the decision to invest in start-up companies the committed capital of the LLCs shareholders. The managing director of the LLC might itself be another LLC or a corporation. The same is true for limited partnerships: The general partner need not be an individual; it can be a legal entity like a corporation.

In sum, LLCs and limited partnerships accomplish the same goal—the pooling of investor capital into a central fund from which to make venture capital investments. The choice is dependent on the type of investor sought. If the venture capitalist wishes to raise funds from a large number of passive and relatively uninformed investors, the limited partnership vehicle is the preferred status. However, if the venture capitalist intends to raise capital from a small group of knowledgeable investors, the LLC is preferred.

The reason is twofold: First, LLCs usually have more specific shareholder rights and privileges. These privileges are best utilized with a small group of well-informed investors. Second, an LLC structure provides shareholders with control over the sale of additional shares in the LLC to new shareholders. This provides the shareholders with more power with respect to the twin issues of increasing the LLCs pool of committed capital and from whom that capital will be committed.

Corporate Venture Capital Funds

With the explosive growth of technology companies in the late 1990s, many of these companies found themselves with large cash balances. Microsoft, for example, had current assets (cash, cash equivalents, and receivables) of over $48 billion, and generated a free cash flow of over $15 billion in 2005. Microsoft and other companies need to invest this cash to earn an appropriate rate of return for their investors.

A corporate venture capital fund is an ideal use for a portion of a company's cash. First, venture capital financing is consistent with Microsoft's own past; it was funded with venture capital over 20 years ago. Second, Microsoft can provide its own technological expertise to help a start-up company. Finally, the start-up company can provide new technology and cost savings to Microsoft. In a way, financing start-up companies allows Microsoft to "think outside of the box" without committing or diverting its own personnel to the task.

Corporate venture capital funds are typically formed only with the parent company's capital; outside investors are not allowed to join. In addition to Microsoft, other corporate venture funds include Xerox Venture Capital, Hewlett-Packard Company. Corporate Investments, Intel Capital, and Amoco Venture Capital. Investments in start-up companies are a way for large public companies to supplement their research-and-development budgets. In addition to accessing to new technology, corporate venture capital funds also gain the ability to generate new products, identify new or diminishing industries, acquire a stake in a future potential competitor, derive attractive returns for excess cash balances, and learn the dynamics of a new marketplace.

Perhaps the best reason for corporate venture capital funds is to gain a window on new technology. Consider the case of Supercomputer Systems of Wisconsin. Steve Chen, the former CEO of Cray Research, left Cray to start his own supercomputer company. Cray Research is a supercomputer company that was itself a spin-off from Control Data Corporation, which in turn was an outgrowth of Sperry Corporation. When Chen founded his new company, IBM was one of his first investors, even though IBM had shifted its focus from large mainframe computers to laptop computers, personal computers, and service contracts (see Schilit, 1998).

Another example is Intel Capital, Intel Corporation's venture capital subsidiary. The goal of Intel Capital is to develop a strategic investment program that focuses on making equity investments and acquisitions to grow the Internet economy, including the infrastructure, content, and services in support of Intel's main business, which is providing computer chips to power personal and laptop computers. To further this goal, Intel Capital has provided venture capital financing to companies like Peregrine Semiconductor Corporation, a start-up technology company that designs, manufactures, and markets high-speed communications integrated circuits for the broadband fiber, wireless, and satellite communications markets.

Since its founding in 1991, Intel Capital has invested more than $4 billion in approximately 1,000 companies in more than 30 countries. Of this 1,000,160 portfolio companies have been acquired and another 150 have gone public on exchanges around the world—a combined success rate of 31% for start-up ventures. Intel Capital's program is sufficiently mature now that Intel has five separate funds from which to seed start-up ventures.

There are, however, several potential pitfalls to a corporate venture capital program. These may include conflicting goals between the venture capital subsidiary and the corporate parent. In addition, the 5- to 10-year investment horizon for most venture capital investments may be a longer horizon than the parent company's short-term profit requirements. Furthermore, a funded startup company may be unwilling to be acquired by the parent company. Still, the benefits from corporate venture capital programs appear to outweigh these potential problems.

Another pitfall of corporate venture capital funds is the risk of loss. Just as every venture capitalist experiences losses in her portfolio of companies, so too will the corporate venture capitalist. This can translate into significant losses for the parent company.

Take the case of Dell Computers. Dell took a charge of $200 million in the second quarter of 2001 as a result of losses from Dell Ventures, the company's venture capital fund. Additionally, in June 2001, Dell reported that its investment portfolio had declined in value by more than $1 billion (see Menn, 2001).

Eventually, Dell decided to exit the venture capital business altogether. It sold the remainder of its venture capital portfolio to Lake Street Capital, a San Francisco private equity firm, for $100 million in 2005.

Intel Corporation reported in 2001 that its technology portfolio had declined more than $7 billion in value. For example, in the second quarter of 2000, Intel reported a $2.1 billion gain from the sale of its venture capital investments. Gains from Intel's technology portfolio helped to keep its earnings growth intact. Conversely, in the second quarter of 2001, Intel reported only a $3 million gain from the sale of its investments from its venture capital subsidiary (see Antonelli, 2001 and Menn, 1998).

However, where Dell did not succeed, Intel has recovered and has rebuilt its venture capital portfolio. In 2005, Intel had over $1 billion of venture capital investments on its financial statements.

Perhaps the most extreme case of nonperforming corporate venture capital investments is that of Comdisco Inc. Comdisco sought bankruptcy protection in July 2001 after making $3 billion in loans to start-up companies that were unable to repay most of the money. The company wrote off $100 million in loans made by its Comdisco Ventures unit, which leases computer equipment to start-up companies. In addition, Comdisco also took a $206 million reserve against earnings from investments in those ventures (see St. Onge, 2001).

Venture Capital Fund of Funds

A venture capital fund of funds is a venture pool of capital that, instead of investing directly in start-up companies, invests in other venture capital funds. The venture capital fund of funds is a relatively new phenomenon in the venture capital industry. The general partner of a fund of funds does not select start-up companies in which to invest. Instead, she selects the best venture capitalists with the expectation that they will find appropriate start-up companies to fund.

A venture capital fund of funds offers several advantages to investors. First, the investor receives broad exposure to a diverse range of venture capitalists and, in turn, a wide range of start-up investing. Second, the investor receives the expertise of the fund of funds manager in selecting the best venture capitalists with whom to invest money. Finally, a fund of funds may have better access to popular, well-funded venture capitalists whose funds may be closed to individual investors. In return for these benefits, investors pay a management fee (and, in some cases, an incentive fee) to the fund of funds manager. The management fee can range from 0.5% to 2% of the net assets managed.

Fund of fund investing also offers benefits to the venture capitalists. First, the venture capitalist receives one large investment (from the venture fund of funds) instead of several small investments. This makes fund raising and investor administration more efficient. Second, the venture capitalist interfaces with an experienced fund of funds manager instead of several (potentially inexperienced) investors.

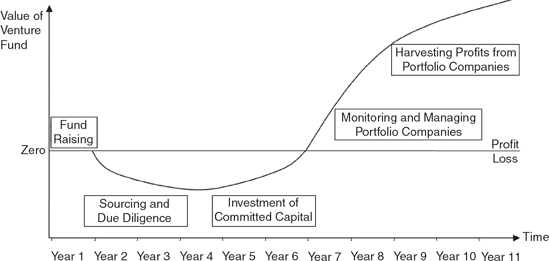

A venture capital fund is a long-term investment. Typically, investors' capital is locked up for a minimum of 10 years—the standard term of a venture capital limited partnership. During this long investment period, a venture capital fund will normally go through five stages of development.

The first stage is the fund-raising stage where the venture capital firm raises capital from outside investors. Capital is committed—not collected. This is an important distinction noted above. Investors sign a legal agreement (typically a subscription) that legally binds them to make cash investments in the venture capital fund up to a certain amount. This is the committed, but not yet drawn, capital. The venture capital firm/general partner will also post a sizeable amount of committed capital.

Fund raising normally takes six months to a year. However, the more successful venture funds such as Kleiner, Perkins, Caufield, and Byers typically fund raise in just two to three months.

The second stage consists of sourcing investments, reading business plans, preparing intense due diligence on start-up companies, and determining the unique selling point of each start-up company. This period begins the moment the fund is closed to investors and normally takes up the first five years of the venture fund's existence.

During stage two, no profits are generated by the venture capital fund. In fact, quite the reverse: The venture capital fund generates losses because the venture capitalist continues to draw annual management fees (which can be up to 3.5% a year on the total committed capital). These fees generate a loss until the venture capitalist begins to extract value from the investments of the venture fund.

Stage three is the investment of capital. During this stage, the venture capitalist determines how much capital to commit to each start-up company, at what level of financing, and in what form of investment (convertible preferred shares, convertible debentures, etc.). At this stage the venture capitalist will also present capital calls to the investors in her venture fund to draw on the capital of the limited partners. Note that no cash flow is generated yet; the venture fund is still in a deficit.

Stage four begins after the funds have been invested and lasts almost to the end of the term of the venture capital fund. During this time the venture capitalist works with the portfolio companies in which the venture capital fund has invested. The venture capitalist may help to improve the management team, establish distribution channels for the new product, refine the prototype product to generate the greatest sales, and generally position the start-up company for an eventual public offering or sale to a strategic buyer. During this time period, the venture capitalist will begin to generate profits for the venture fund and its limited partner investors. These profits will initially offset the previously collected management fees until a positive net asset value is established for the venture fund.

The last stage of the venture capital fund is its windup and liquidation. At this point, all committed capital has been invested and now the venture capitalist is in the harvesting stage. Each portfolio company is either sold to a strategic buyer, brought to the public markets in an IPO, or liquidated through a Chapter 7 bankruptcy liquidation process. Profits are distributed to the limited partners and the general partner/venture capitalist now collects her incentive/profit-sharing fees.

These stages of a venture capital firm lead to what is known as the "J curve effect." Figure 54.1 demonstrates the J curve. We can see that during the early life of the venture capital fund, it generates negative revenues (losses), but eventually, profits are harvested from successful companies and these cash flows overcome the initial losses to generate a net profit for the fund. Clearly, given the initial losses that pile up during the first four to five years of a venture capital fund, this type of investing is only for patient, long-term investors.

Like any industry that grows and matures, expansion and maturity lead to specialization. The trend toward specialization in the venture capital industry exists on several levels: by industry geography stage of financing, and "special situations." Specialization is the natural by-product of two factors. First, the enormous amount of capital flowing into venture capital funds has encouraged venture capitalists to distinguish themselves from other funds by narrowing their investment focus. Second, the development of many new technologies over the past decade has encouraged venture capitalists to specialize in order to invest most profitably.

Specialization by Industry

Specialization by entrepreneurs is another reason why venture capitalists have tailored their investment domain. Just as entrepreneurs have become more focused in their start-up companies, venture capitalists have followed suit. The biotechnology industry is a good example.

The biotech industry was born on October 14,1980, when the stock of Genentech, Inc. went public. On that day, the stock price went from $39 to $85 and a new industry was born. Today, Genentech is a Fortune 500 company with a market capitalization of $28 billion. Other successful biotech start-ups include Cetus Corporation, Biogen, Inc., Amgen Corporation, and Centacor, Inc.

The biotech paradigm has changed since the days of Genentech. Genentech was founded on the science of gene mapping and splicing to cure diseases. However, initially it did not have a specific product target. Instead, it was concerned with developing its gene-mapping technology without a specific product to market.

Compare this situation to that of Applied Microbiology, Inc. of New York. It has focused on two products with the financial support of Merck and Pfizer, two large pharmaceuticals (see Schilit, 1997). One of its products is an antibacterial agent to fight gum disease contained in a mouth wash to be marketed by Pfizer.

Specialized start-up biotech firms have led to specialized venture capital firms. For example, Domain Associates of Princeton, New Jersey, focuses on funding new technology in molecular engineering. However, specialization is not unique to the biotech industry. Other examples include Communication Ventures of Menlo Park, California. This venture firm provides financing primarily for start-up companies in the telecommunications industry. Another example is American Health Capital Ventures of Brentwood, Tennessee, that specializes in funding new health care companies.

Specialization by Geography

With the boom in technology companies in Silicon Valley, Los Angeles, and Seattle, it is not surprising to find that many California-based venture capital firms concentrate their investments on the west coast of the United States. Not only are there plenty of investment opportunities in this region, it is also easier for the venture capital firms to monitor their investments locally. The same is true for other technology centers in New York, Boston, and Texas.

As another example, consider Marquette Ventures based in Chicago. This venture capital company invests primarily with start-up companies in the Midwest. Although it has provided venture capital financing to companies outside of this region, its predominant investment pattern is with companies located in the midwestern states (see Schilit, 1997). Similarly, the Massey Birch venture capital firm of Nashville, Tennessee, has provided venture financing to a number of companies in its hometown of Nashville as well as other companies throughout the southeastern states.

Regional specialization has the advantage of easier monitoring of invested capital. Also, larger venture capital firms may overlook viable start-up opportunities located in more remote sections of the United States. Regional venture capitalists step in to fill this niche.

The downside of regional specialization is twofold. First, regional concentration may not provide sufficient diversification to a venture capital portfolio. Second, a start-up company in a less exposed geographic region may have greater difficulty in attracting additional rounds of venture capital financing. This may limit the start-up company's growth potential as well as exit opportunities for the regional venture capitalist.

Special Situation Venture Capital

In any industry, there are always failures. Not every startup company makes it to the IPO stage. However, this opens another specialized niche in the venture capital industry: the turnaround venture deal. Turnaround deals are as risky as seed financing because the start-up company may be facing pressure from creditors. The turnaround venture capitalist exists because mainstream venture capitalists may not be sufficiently well versed in restructuring a turnaround situation.

Consider the following example. (A similar example is in Schilit [1997].) A start-up company is owned 50% by early and midstage venture capitalists and 50% by the founder. Product delays and poor management have resulted in $10 million in corporate assets and $15 million in liabilities. The company has a negative net worth and is technically bankrupt.

The turnaround venture capitalist offers the founder/ entrepreneur of the company $1 million for his 50% ownership plus a job as an executive of the company. The turnaround venture capitalist then offers the start-up company's creditors 50 cents for every one dollar of claims. The total of $8.5 million might come from a $1 million contribution from the turnaround venture capitalist and $7.5 million in bank loans secured by the $10 million in assets. Therefore, for $1 million the turnaround venture capitalist receives 50% of the start-up company and restores it to a positive net worth.

The founder of the company is happy because he receives $1 million for a bankrupt company plus he remains as an executive. The other venture capitalists are also happy because now they will be dealing with another venture specialist, plus the company has been restored to financial health. With some additional hard work the company may proceed on to an IPO. The creditors, however, will not be as pleased, but may make the deal anyway because 50 cents on the dollar may be more than they could expect to receive through a formal liquidation procedure.

An example of such a turnaround specialist is Reprise Capital Corporation of Garden City New Jersey. In 1997, this company raised $25 million for turnaround venture capital deals.

In summary, the growth of the venture capital industry has created the need for venture capital specialists. The range of new business opportunities is now so diverse that it is simply not possible for a single venture capital firm to stay on top of all opportunities in all industries. Therefore, by necessity, venture capitalists have narrowed their investment domain to concentrate on certain niches within the start-up universe. Specialization also leads to differentiation, which allows venture capitalists to distinguish themselves from other investment funds.

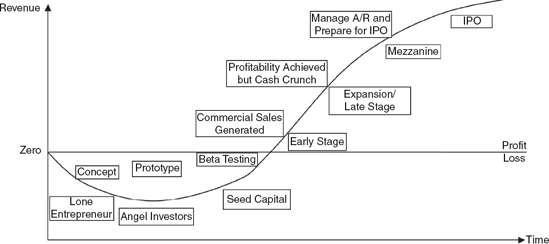

While some venture capital firms classify themselves by geography or industry, by far the most distinguishing characteristic of venture capital firms is the stage of financing. Some venture capitalists provide first-stage or "seed capital," while others wait to invest in companies that are further along in their development. Still other venture capital firms come in at the final round of financing before the IPO. A different level of due diligence is required at each level of financing because the start-up venture has achieved another milestone on its way to success. In all, there are five discrete stages of venture capital financing: angel investing, seed capital, first-stage capital, late-stage/expansion capital, and mezzanine financing. We discuss each of these separately below.

Angel investors often come from "F & F": friends and family. (Sometimes, venture capitalists include a third "F" for fools.) At this stage of the new venture, typically there is a lone entrepreneur who has just an idea—possibly sketched out at the kitchen table or in the garage. There is no formal business plan, no management team, no product, no market analysis—just an idea.

In addition to family and friends, angel investors can also be wealthy individuals who "dabble" in start-up companies. This level of financing is typically done without a private placement memorandum or subscription agreement. It may be as informal as a "cocktail napkin" agreement. Yet without the angel investor, many ideas would wither on the vine before reaching more traditional venture capitalists.

At this stage of financing, the task of the entrepreneur is to begin the development of a prototype product or service. In addition, the entrepreneur begins the draft of his business plan, assesses the market potential, and may even begin to assemble some key management team members. No marketing or product testing is done at this stage.

The amount of financing at this stage is very small— $50,000 to $500,000. Any more than that would strain family, friends, and other angels. The funds are used primarily to flush out the concept to the point where an intelligent business plan can be constructed.

Seed capital is the first stage where venture capital firms invest their capital. At this stage, a business plan is completed and presented to a venture capital firm. Some parts of the management team have been assembled at this point, a market analysis has been completed, and other points of the business plan as discussed previously in this chapter are addressed by the entrepreneur and his small team. Financing is provided to complete the product development and, possibly, to begin initial marketing of the prototype to potential customers. This phase of financing usually raises $1 to $5 million.

At this stage of financing, a prototype may have been developed and the testing of a product with customers may have begun. This is often referred to as "beta testing," and is the process where a prototype product is sent to potential customers free of charge to get their input into the viability, design, and user friendliness of the product.

Very little revenue has been generated at this stage, and the company is definitely not profitable. Venture capitalists invest in this stage based on their due diligence of the management team, their own market analysis of the demand for the product, the viability of getting the product to the market while there is still time and not another competitor, the additional management team members that will need to be added, and the likely timing for additional rounds of capital from the same venture capital firm or from other venture capital funds.

Examples of seed financing companies are Technology Venture Investors of Menlo Park, California; Advanced Technology Ventures of Boston; and Onsent, located in Silicon Valley (Schilit, 1997). Seed capital venture capitalists tend to be smaller firms because large venture capital firms cannot afford to spend the endless hours with an entrepreneur for a small investment that usually is no greater than $1 to $2 million.

At this point the start-up company should have a viable product that has been beta tested. Alpha testing may have already begun. This is the testing of the second-generation prototype with potential end users. Typically, a price is charged for the product or a fee for the service. Revenues are being generated and the product/service has now demonstrated commercial viability. Early-stage venture capital financing is usually $2 million or more.

Early-stage financing is typically used to build out the commercial scale manufacturing services. The product is no longer being produced out of the entrepreneur's garage or out of some vacant space above a grocery store. The company is now a going concern with an initial, if not complete, management team. At this stage, there will be at least one venture capitalist sitting on the board of directors of the company.

The goal of the start-up venture is to achieve market penetration with its product. Some of this will have already been accomplished with the beta and alpha testing of the product. However, additional marketing must now be completed. In addition, distribution channels should be identified by now and the product should be established in these channels. Reaching a breakeven point is the financial goal.

At this point, the start-up company may have generated its first profitable quarter, or be just at the breakeven point. Commercial viability is now established. Cash flow management is critical at this stage, as the company is not yet at the level where its cash flows can self-sustain its own growth.

Late-stage/expansion capital fills this void. This level of venture capital financing is used to help the start-up company get through its cash crunch. The additional capital is used to tap into the distribution channels, establish call centers, expand the manufacturing facilities, and attract the additional management and operational talent necessary to the make the start-up company a longer-term success. Because this capital comes in to allow the company to expand, financing needs are typically greater than for seed and early stage. Amounts may be in the $5 million to $15 million range.

At this stage, the start-up venture enjoys the growing pains of all successful companies. It may need additional working capital because it has focused on product development and sales, but now finds itself with a huge back-load of accounts receivable from customers on which it must now collect. Inevitably, start-up companies are very good at getting the product out of the door but very poor at collecting receivables and turning sales into cold, hard cash.

Again, this is where expansion capital can help. Late-stage venture financing helps the successful start-up get through its initial cash crunch. Eventually, the receivables will be collected and sufficient internal cash will be generated to make the start-up company a self-sustaining force. Until then, one more round of financing may be needed.

Mezzanine venture capital is the last stage before a startup company goes public or is sold to a strategic buyer. At this point, a second-generation product may already be in production if not distribution. The management team is together and solid, and the company is working on managing its cash flow better. Manufacturing facilities are established, and the company may already be thinking about penetrating international markets. Amounts vary depending on how long the bridge financing is meant to last but generally is in the range of $5 to $15 million.

The financing at this stage is considered "bridge" or mezzanine financing to keep the company from running out of cash until the IPO or strategic sale. The start-up company may still have a large inventory of uncollected accounts receivable that need to be financed in the short term. Profits are being recorded, but accounts receivable are growing at the same rate of sales.

Mezzanine financing may be in the form of convertible debt. In addition, the company may have sufficient revenue and earning power that traditional bank debt may be added at this stage. This means that the start-up company may have to clean up its balance sheet as well as its statement of cash flows. Commercial viability is more than just generating sales, it also requires turning accounts receivable into actual dollars.

Figure 54.2 presents the J curve for a start-up company. Similar to the J curve for a venture capital fund, the initial years of a start-up company generate a loss. Money is spent turning an idea into a prototype product and from there beta testing the product with potential customers. Little or no revenue is generated during this time. It is not until the product goes into alpha testing that revenues may be generated and the start-up becomes a viable concern.

Once a critical mass is generated—where sales are turned into profits and accounts receivable is turned into cash—then it becomes a matter of timing until the start-up company achieves a public offering. Additional rounds of financing may be needed to get the company to its IPO nirvana. At this point, commercial viability is established, but managing the cash crunch becomes critical.

Venture capital investing is a natural part of the equity cycle. Every company has to start someplace with some amount of capital to finance its initial operations. Long before a successful company reaches traditional investors in an IPO, venture capitalists are hard at work providing strategy, financing, and direction to start-up companies. Without the acorn of venture capital, most start-up companies would wither on the vine and their products would not come to fruition.

Also, venture capital plays a role in economic Darwinism. Because venture capitalists are rewarded only for those technologies and ideas that will have the greatest economic impact on society, they prune out the weak ideas and technology. Only the strong ideas survive—and these are the ideas, products, services, and technologies that will reward the venture capitalist the greatest while serving society to the largest extent possible.

Anson, M. J. P. (2006). Handbook of Alternative Assets, 2nd edition. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons.

Antonelli, C. (2001). Chipmaker's profit plunges 94%; Intel still beats analysts' forecasts. Bloomberg News, July 18.

British Venture Capital Association. (2004). A guide to private equity. White paper, October.

Lerner, J. (2000). Venture Capital and Private Equity. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Lipin, S. (2000). Venture capitalists "R" us. Wall Street Journal, February 22: Cl.

Menn, J. (2001). Tech giants lose big on start-up ventures. Los Angeles Times, June 11.

Schilit, K. W (1997). The nature of venture capital investments. Journal of Private Equity, Winter: 59-75.

Schilit, K. W (1998). Structure of the venture capital industry. Journal of Private Equity, Spring: 60-67.

St. Onge, J. (2001). Comdisco seeks bankruptcy protection from creditors. Bloomberg News, July 16.