JEFF COHEN

Securities Lending Manager, Susquehanna Intl Group, LLLP

DAVID HAUSHALTER, PhD

Corporate Research and Educational Associate, Susquehanna Intl Group, LLLP

ADAM V. REED, PhD

Assistant Professor of Finance, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Abstract: Short selling involves a transaction outside the stock market; short sellers borrow stock for delivery to buyers. The equity lending market allows short sellers and other market participants to borrow shares from stock owners for a price. Supply and demand factors determine each loan's price. Since supply of shares is usually high, most loans have low prices. However, episodic events can lead to significantly higher prices. Although there are risks for borrowers and lenders in the equity loan market, cash collateral allows the risk for lenders to be minimized.

Keywords: equity loans, securities lending, short sales, delivery, settlement, rebate rate, specialness, delivery failure

Short sellers sell stock they do not own. The equity lending market exists to match these short sellers with owners of the stock willing to lend their shares for a fee. Despite its obvious importance to the operation of financial markets, the equity lending market is arcane. The market is dominated by loans negotiated over the phone between borrowers and lenders. Although there have been significant improvements in recent years, there is no widely used electronic quote or trade network in the equity lending market.

In this chapter, we discuss the mechanics of equity loans, the participants and their roles, and how rebate rates (prices) are determined in the market.

An investor who wants to sell a stock short must first find a party willing to lend the shares. One exception to this rule is for market makers. For example, the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) requires affirmative determination (a locate) of borrowable or otherwise attainable shares for members who are not market makers, specialists or odd lot brokers in fulfilling their market-making responsibilities. Similar rules exist for the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD) and American Exchange (AMEX) (see Evans et al., 2003).

Once a lender has been located and the shares are sold short, exchange procedures generally require that the short-seller deliver shares to the buyer on the third day after the transaction (t + 3) and post an initial margin requirement at its brokerage firm. Under Regulation T, the initial margin requirement is 50%. Self-regulatory organizations (e.g., NYSE and NASD) require the short seller to maintain a margin of at least 30% of the market value of the short position as the market price fluctuates.

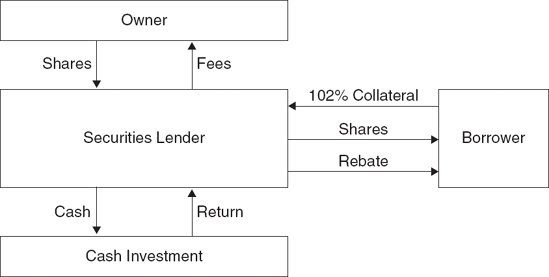

As described in Figure 70.1, the proceeds from the short sale are deposited with the lender of the stock. For U.S. stocks, the lender requires 102% of the value of the loan in collateral. The value of the loan is marked to market daily; an increase in the stock price will result in the lender requiring additional collateral for the loan, and a decrease in the stock price will result in the lender returning some of the collateral to the borrower. When the borrower returns the shares to the lender, the collateral will be returned.

While a stock is on loan, the lender invests the collateral and receives interest on this investment. Generally, the lender returns part of the interest to the borrower in the form of a negotiated rebate rate. Therefore, rather than fees, the primary cost to the borrower is the difference between the current market interest rate and the rebate rate the lender pays the borrower on the collateral. A lender's benefit from participating in this market is the ability to earn the spread between these rates. Although the earnings from this interest spread are often split between several parties participating in the lending process, the interest can add low risk return to a lender's portfolio.

Traditionally, custodian banks that clear and hold positions for large institutional investors have been the largest equity lenders. With the beneficial owner's permission, custodian banks can act as lending agents for the beneficial owners by lending shares to borrowers. The custodian bank and the beneficial owners share in any revenue generated by securities lending with a prearranged fee sharing agreement. A typical arrangement would have 75% of the revenue going to the beneficial owner and 25% going to the agent bank (see Bargerhuff & Associates, 2000). Depending on the type of assets being lent and the borrowing demand, lending revenue earned by the owner of the security may completely offset custodial and clearance fees for institutional investors.

In addition to traditional custodian bank lenders, a number of specialty third-party agent lenders have entered the equity lending market over the past several years. Under this structure, the assets are lent by an agent firm who represents the beneficial owner but is not the custodian of the assets. Once a loan is negotiated between the agent lender and the borrower, the agent facilitates settlement by working with a traditional custodian bank in arranging delivery of the shares to the borrower. In comparison with custodian banks, these noncustodial lenders often offer advantages to the beneficial owner such as more specialized reporting, flexibility, and more lending revenue.

As an alternative to agency-lending arrangements, the beneficial owner may decide to lend assets directly to borrowers. Increasingly, owners choose to lend their assets via an exclusive arrangement, where the owner commits his assets to one particular borrower for a specific period of time. For example, in recent years, the California Public Employees Retirement System (CalPERS) has lent its portfolios through an auction system with the winning bidder gaining access to the portfolio for a predetermined period of time. This arrangement guarantees a return to the beneficial owner for loaning out the assets. Another avenue that some institutions have explored is managing their own internal lending department, therefore having total control over the lending process and keeping all of the revenues generated. Due to the large costs involved in setting up a lending department and the infrastructure needed, this option is only available to the largest institutional investors.

The owner of a stock retains beneficial ownership of the shares it lends. This status gives the owner the right to receive the value of any dividends or distributions paid by the issuing company while the stock is on loan. However, rather than being paid by the company, the dividend and distributions are paid by the borrower. This is referred to as a "substitute payment." The beneficial owner is also entitled to participate in any corporate actions that occur while the security is on loan. For example, in the case of a tender offer, if the beneficial owner wishes to participate in the offer and the borrower is unable to return the security prior to the completion of the offer, the borrower is required to pay the beneficial owner the tender price. The only right the lender gives up when lending their assets is the right to vote on a security. (For a discussion of lending and voting, see Christoffersen et al. [2004J.) However, the lender generally has the right to recall the loaned security from the borrower for any reason, including to exercise voting rights.

In the event of a recall, the borrower is responsible for returning the shares to the lender within the normal settlement cycle. For example, if the beneficial owner sells a security that is on loan, the agent lender will send a recall notice to the borrower on the first business day after the trade date (T + 1) instructing borrower that the shares need to be returned to the agent within two business days (T + 3). If the shares are returned within this period, the custodian can settle the pending sell trade. If the borrower fails to return the shares by (T + 3), the agent may buy shares to cover the position, therefore closing out the loan.

There are three types of risk the beneficial owner faces when lending stock: investment risk, counterparty risk, and operational risk. Investment risk involves the choices that the beneficial owner or their agent makes in investing collateral. Some lenders are reluctant to take risk in their reinvestment of collateral, and they invest primarily in overnight repurchase agreements or other very low risk investments. Other lenders look to achieve extra income by investing in higher risk assets. For example, lenders can earn more return by investing in longer term investments and short-term corporate debt with lower credit ratings. It is the beneficial owner's responsibility to monitor the investment of the collateral to manage these risks. Even if there is a loss from investing the borrower's collateral, the beneficial owner is still responsible for returning the borrower's full collateral when the security is returned. An example of this risk is provided by Citibank which, acting as an agent lender, is estimated to have lost approximately $80 million in collateral on an investment in asset-backed security issued by National Century Financial Enterprises. After this event occurred, it was unclear whether Citibank would cover the beneficial owners for this loss of collateral.

Counterparty risk is the risk that the borrower fails to provide additional collateral or fails to return the security. The beneficial owner can manage this risk by approving only the most creditworthy borrowers and by imposing credit limits on these borrowers. Furthermore, the fact that collateral is marked to market daily allows lenders to buy shares to cover the loan if the borrower will not return the shares.

The last major risk to the beneficial owner is operational risk. This is the risk that various responsibilities of the agent lender or borrower are not met. This could be the failure to collect dividend payments, the failure to instruct clients on corporate actions resulting in missed profit opportunities, the failure to mark a loan to market, and the failure to return a security in the event of a recall. These risks can be minimized by maintaining a good lending system which tracks dividends, corporate actions, and the collateralization of loans.

The largest borrowers of stocks are prime brokerage firms facilitating the short demand for their own proprietary trading desks, for their hedge fund clients, and for other leveraged investors. Trading desks often borrow stock to enable long-short trading strategies. Furthermore, tremendous growth in the hedge fund industry during the past decade has resulted in an increase in the use of other sophisticated strategies that require borrowing stock according to a September 2003 staff report of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on hedge funds. Because lending firms are reluctant to approve hedge funds as creditworthy borrowers, hedge funds have traditionally used prime brokers to gain access to the lending markets.

The two risks that a borrower faces are the risk of a loan recall and the risk of a decrease in rebate rates. A borrower's challenge is to find a lender that best balances these risks. Recall risk is the risk of the stock's, being recalled by the lender before the borrower is prepared to close out his position, which happens in approximately 2% of the loans in the sample of a study by D'Avolio (2002). Borrowers would prefer to have loans lasting the duration of the short position, but guaranteed term loans are rare. (For a discussion of loan terms, see D'Avolio (2002) and Geczy, Musto, and Reed [2002J.) So, borrowers need to manage recall risk by working with a lender that is likely to be willing to loan the stock for an extended period of time. Often, the most stable sources of stock loans are portfolios with little turnover, such as index funds.

There are no rules governing which loans will be recalled if a beneficial owner recalls its stock. If the agent for the lender has loaned the stock to several prime brokerage firms and some of those shares need to be returned, the lending agent has discretion in deciding which prime brokers' loans will be recalled. Moreover, if the prime broker, whose loan has been selected, has allocated these shares to several borrowers, the broker has flexibility in selecting which of the borrowers will have their shares recalled. If the borrower's loan does get recalled by the lender, it is the borrowers' responsibility to return shares to the lender either by buying shares in the market or by borrowing the shares from another lender. If the borrower fails to return the shares, the lender can use the borrower's collateral to buy shares to cover the loan, which is known as a buy-in. In other words, recalls can force borrowers to unwind their trading strategies suboptimally or expose the borrowers to potentially poor execution in the case of a buy-in.

The rebate rate, or the rate a borrower is paid on his cash collateral, effectively determines the price of a stock loan. This rate is determined by supply and demand in the market for borrowing stock. For highly liquid stocks that are widely held by institutional lenders, the borrower can expect to earn the full rebate or general collateral rate, on the collateral. This rate is generally 5 to 25 basis points below the Fed funds rate for each day. (In a Fitch IBCA's report ("Securities Lending and Managed Funds") it is estimated that the industry average spread from the Fed funds rate to the general collateral rate on U.S. equities is 21 basis points.) When there is less available supply in the equity lending market, as with middle-capitalization stocks, the spread generally increases to around 35 basis points according to Bargerhuff & Associates (2000).

The majority of loans in the equity lending market are made in widely held stocks that are cheap to borrow. However, on less widely held securities or securities with large borrowing demand, rebate rates may be reduced, in which case, the securities are said to be "trading special" or just "special." This means that the rebate rate is negotiated on a case by case basis, and the rate earned by the borrower on the collateral is below the general collateral rate paid on easily available securities. Only a few stocks are on special each day; a one-year sample in a study by Geczy, Musto, and Reed (2002) had approximately 7% of its securities on special. And, the specials aren't necessarily limited to small stocks; 2.77% of large stocks were found to be on special in the same sample (Reed, 2003). In rare cases, when a stock is in high demand, the rebate rate can be significantly negative. For example, shares of Stratos Lightwave, Inc. had a rebate rate more than 4,000 basis points below the general collateral rate in late August 2000, just after the firm's initial public offering (IPO) (see Mitchell, Pulvino, and Stafford, 2002). In these cases, the lender is keeping the full investment rate of return on the collateral and also earning a premium for lending the securities.

Although specials are identified by their low rebate rates, the difficulty of borrowing specials goes beyond the increase in borrowing costs. Only well-placed investors (e.g., hedge funds) will be able to borrow specials and receive the reduced rebate. Generally, brokers will not borrow special shares on behalf of small investors; the order to short sell will be denied. Loans in stock specials will be expensive for well-placed investors and impossible to obtain for retail investors.

Specials tend to be driven by episodic corporate events that increase the demand for stock loans or reduce the supply of stocks available for loan. For example, initial public offerings, dividend reinvestment discount programs, and dividend payments of foreign companies often lead to an increase in borrowing demand and/or a reduction in the supply of available shares. In the case of IPOs, even though shares are available in the first settlement days, they are generally on special. At issuance, the average IPO's rebate rate is 300 basis points below the general collateral rate, but this spread from the general collateral rate falls to 150 basis points within the first 25 trading days. Similarly, the short selling of merger acquirers' stock drives specialness. Loans of merger acquirers' stock have average rebate rates 23 basis points below general collateral rates according to Geczy, Musto, and Reed (2002). Additionally, because brokers prohibit their clients from buying stocks with prices below $5 on margin, there can be a limited supply of stock available for loan from broker dealers for these low-price shares. (Broker dealers usually have the right to loan out any stock held in individual investors' margin accounts. However, shares that are paid in full cash rather than in margin accounts are generally not available to borrow from a broker dealer without consent of the owner.) Some factors that can improve liquidity in a stock and therefore improve its rebate rate include a secondary issue of the security, an expiration of an IPO lock-up period, and the reduction in short-selling demand as a result of the completion of a merger or corporate action.

As investors continue to become more sophisticated and new arbitrage opportunities develop, the securities lending markets will continue to expand and see new entrants. Beneficial owners have been increasing their participation in the lending markets, and they view the market as a low risk way to achieve increased return on their assets. Broker-dealers eager to attract the very profitable client base of hedge funds and other leveraged investors continue to expand their securities lending infrastructures. As a result, the securities lending markets have seen tremendous growth over the last decade. New entrants on both the lending and borrowing side combined with new technologies improving the transparency in the lending markets continue to increase the importance of this market.

D'Avolio, G. (2002). The market for borrowing stock. Journal of Financial Economics 66 (November): 271-306.

Duffie, D., Garleanu, N., and Pedersen, L. (2002). Securities lending, shorting, and pricing. Journal of Financial Economics 66 (November): 307-339.

Bargerhuff & Associates (2000). Securities Lending Analytics: 2nd Quarter.

Christoffersen, S., Geczy, C., Musto, D., and Reed, A. (2005). Crossborder dividend taxation and the preferences of taxable and nontaxable investors: Evidence from Canada. Journal of Financial Economics 78:121-144.

Christoffersen, S., Geczy, C, Musto, D., and Reed, A. (2007). Vote trading and information aggregation. Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Evans, R., Geczy, C, Musto, D., and Reed, A. (2005). Failure is an option: Impediments to short-selling and options prices. Review of Financial Studies, forthcoming.

Fabozzi, F. J. and Mann, S. V. (eds.). (2005). Securities Finance: Securities Lending and Repurchase Agreements. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Geczy, C, Musto, D., and Reed, A. (2002). Stocks are special too: An analysis of the equity lending market. Journal of Financial Economics 66 (November): 241-269.

Jones, C, and Lamont, O. (2002). Short sale constraints and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics 66 (November): 207-239.

Lamont, O. (2004). Short sale constraints and overpricing. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Short Selling: Strategies, Risks, and Rewards (pp. 179-204). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mitchell, M., Pulvino, T., and Stafford, E. (2003). Limited arbitrage in equity markets. Journal of Finance 57, 2: 551-584.

Reed, A. (2003). Costly short selling and stock price adjustment to earnings announcements. University of North Carolina working paper (June).