FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

Abstract: Debt obligations are issued by state and local governments and by entities that they establish. These securities are referred to as municipal securities or municipal bonds. The two general types of municipal bond structures are tax-backed securities and revenue bonds. There are also municipal bonds with special bond structures. The primary attractiveness of municipal bonds is that the interest earned is exempt from federal income taxation. While not all municipal securities are exempt from federal income taxation, tax-exempt municipal bonds are the largest component of the market.

Keywords: municipal bonds, tax-backed debt obligations, revenue bonds, general obligation debt, Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB), taxable municipal bonds, original-issue discount (OID) bond, alternative minimum taxable income (AMTI), alternative minimum tax (AMT), official statement, municipal notes, variable rate demand obligations (VRDOs), utility revenue bonds, transportation revenue bonds, housing revenue bonds, higher education revenue bonds, health care revenue bonds, seaport revenue bonds, insured bonds, letter of credit (LOC), bank-backed municipal bonds, refunded bonds, equivalent taxable yield, tender option bonds (TOBs), inverse floater, residual, effective marginal tax rate, structure risk, tax risk

In this chapter, we discuss the types of debt obligations issued by states, municipal governments, and public agencies and their instrumentalities and the investment characteristics of these financial instruments.

Issuers of municipal bonds include municipalities, counties, towns and townships, school districts, and special service system districts. Included in the category of municipalities are cities, villages, boroughs, and incorporated towns that received a special state charter. Counties are geographical subdivisions of states whose functions are law enforcement, judicial administration, and construction and maintenance of roads.

As with counties, towns and townships are geographical subdivisions of states and perform similar functions as counties. A special purpose service system district, or simply special district, is a political subdivision created to foster economic development or related services to a geographical area. Special districts provide public utility services (water, sewers, and drainage) and fire protection services. Public agencies or instrumentalities include authorities and commissions.

The number of municipal bond issuers is remarkable: more than 60,000. Even more noteworthy is the number of different issues: more than 1.3 million. There are more than 50,000 bonds that are priced in the Standard & Poor's Investortools Main Municipal Bond Index (see Garrett, 2008).

The Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB) regulates various aspects of the municipal bond market including municipal securities brokers and dealers. The MSRB was established in 1975 by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as a self-regulatory organization pursuant to a Congressional directive. It adopts rules to (1) prevent fraudulent and manipulative acts and practices, (2) promote fair and equitable principles for the trading of municipal securities, and (3) protect investors and the public interest. (For a detailed discussion of the MSRB, see Maco and Taffe [2008].)

Municipal bonds are issued in one of three ways: negotiated sale, competitive bidding, or private placement. In a negotiated sale, an investment banker is retained by the issuer to underwrite the issue and then sell the bonds to the public. In a competitive bidding, investment bankers bid on an issue, the winning bidder being the investment bank that bids the lowest interest rate (or equivalent, the highest price). The investment bank or syndicate that wins the issue then distributes the securities to the public. In a private placement, a method typically reserved for small-size bond issues and accounting for less than 1% of all new issuance, the issue is placed directly with one or more institutional investors. An issuer may not have a choice as to which method to use. A state may mandate certain types of bonds be issued using a particular method. For example, some states will mandate that the state's general obligation bonds be sold via competitive bidding (see Peng and Brucato, 2001). Peng, Kriz, and Neish (2008) provide a detailed description of the factors municipal issues consider in selecting between a competitive bidding and negotiated sale.

There are both tax-exempt and taxable municipal securities. "Tax-exempt" means that interest on a municipal security is exempt from federal income taxation. The tax exemption of municipal securities applies to interest income, not capital gains. The exemption may or may not extend to taxation at the state and local levels. The state tax treatment depends on (1) whether the issue from which the interest income is received is an "in-state issue" or an "out-of-state issue," and (2) whether the investor is an individual or a corporation. The treatment of interest income at the state level will be one of the following:

Taxation of interest from municipal issues regardless of whether the issuer is in state or out of state.

Exemption of interest from all municipal issues regardless of whether the issuer is in state or out of state.

Exemption of interest from municipal issues that are in state but some form of taxation where the source of interest is an out-of-state issuer.

However, the differential tax treatment of interest from in-state and out-of-state bond issues has been challenged. In Kentucky, a state court ruled that the state apply the same tax treatment to interest from both types of issuers. In August 2006, the Kentucky Supreme Court let that ruling stand. Kentucky has appealed the decision to the United States Supreme Court, which considered the case in October 2007. If the ruling stands, then only 1 and 2 above will be permitted by states.

Most municipal securities that have been issued are tax-exempt. Municipal securities are commonly referred to as tax-exempt securities although taxable municipal securities have been issued and are traded in the market. Municipalities issue taxable municipal bonds to finance projects that do not qualify for financing with tax-exempt bonds. An example is a sports stadium. The most common types of taxable municipal bonds are industrial revenue bonds and economic development bonds. Since there are federally mandated restrictions on the amount of tax-exempt bonds that can be issued, a municipality will issue taxable bonds when the maximum is reached. There are some issuers who have issued taxable bonds in order to take advantage of demand outside of the United States.

There are other types of tax-exempt bonds. These include bonds issued by nonprofit organizations. Such organizations are structured so that none of the income from the operations of the organization benefit an individual or private shareholder. The designation of a nonprofit organization must be obtained from the Internal Revenue Service. Since the tax-exempt designation is provided pursuant to Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code, the tax-exempt bonds issued by such organizations are referred to as 501(c)(3) obligations. Museums and foundations fall into this category. Tax-exempt obligations also include bonds issued by the District of Columbia and any possession of the United States—Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands. The interest income from securities issued by U.S. territories and possessions is exempt from federal, state, and local income taxes in all 50 states.

Federal tax rates and the treatment of municipal interest at the state and local levels affect municipal security values and strategies employed by investors. There are provisions in the Internal Revenue Code that investors in municipal securities should recognize. These provisions deal with original issue discounts, the alternative minimum tax, and the deductibility of interest expense incurred to acquire municipal securities.

If at the time of issuance the original-issue price is less than its maturity value, the bond is said to be an original-issue discount (OID) bond. The difference between the par value and the original-issue price represents tax-exempt interest that the investor realizes by holding the issue to maturity.

For municipal bonds there is a complex treatment that investors must recognize when purchasing OID municipal bonds. The Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1993 specifies that any capital appreciation from the sale of a municipal bond that was purchased in the secondary market after April 30, 1993, could be either (1) free from any federal income taxes, (2) taxed at the capital gains rate, (3) taxed at the ordinary income rate, or (4) taxed at a combination of the two rates.

The key to the tax treatment is the rule of de minimis for any type of bond. The rule states that a bond is to be discounted up to 0.25% from the par value for each remaining year of a bond's life before it is affected by ordinary income taxes. The discounted price based on this rule is called the market discount cutoff price. The relationship between the market price at which an investor purchases a bond, the market discount cutoff price, and the tax treatment of the capital appreciation realized from a sale is as follows. If the bond is purchased at a market discount, but the price is higher than the market discount cutoff price, then any capital appreciation realized from a sale will be taxed at the capital gains rate. If the purchase price is lower than the market discount cutoff price, then any capital appreciation realized from a sale may be taxed as ordinary income or a combination of the ordinary income rate and the capital gains rate. (Several factors determine what the exact tax rate will be in this case.)

The market discount cutoff price changes over time because of the rule of de minimis. The price is revised. An investor must be aware of the revised price when purchasing a municipal bond because this price is used to determine the tax treatment.

Alternative minimum taxable income (AMTI) is a taxpayer's taxable income with certain adjustments for specified tax preferences designed to cause AMTI to approximate economic income. For both individuals and corporations, a taxpayer's liability is the greater of (1) the tax computed at regular tax rates on taxable income and (2) the tax computed at a lower rate on AMTI. This parallel tax system, the alternative minimum tax (AMT), is designed to prevent taxpayers from avoiding significant tax liability as a result of taking advantage of exclusions from gross income, deductions, and tax credits otherwise allowed under the Internal Revenue Code.

One of the tax preference items that must be included is certain tax-exempt municipal interest. As a result of AMT, the value of the tax-exempt feature is reduced. However, the interest of not all municipal issues is subject to the AMT. Under the current tax code, tax-exempt interest earned on all private activity bonds issued after August 7, 1986 must be included in AMTI. There are two exceptions. First, interest from bonds that are issued by 501(c)(3) organizations (that is, not-for-profit organizations) is not subject to AMTI. The second exception is interest from bonds issued for the purpose of refunding if the original bonds were issued before August 7, 1986. The AMT does not apply to interest on governmental or nonprivate activity municipal bonds. An implication is that those issues that are subject to the AMT will trade at a higher yield than those exempt from AMT.

For investors in mutual funds that invest in municipal bonds, the prospectus will disclose whether the fund's manager is permitted to invest in AMT bonds and if it permitted, the maximum amount. Usually, when a mutual fund allows investments in AMT bonds, the maximum is 20%. The year-end 1099 form provided to investors in mutual funds will show the percentage of the income of the fund must be included in AMTI.

Ordinarily, the interest expense on borrowed funds to purchase or carry investment securities is tax deductible. There is one exception that is relevant to investors in municipal bonds. The Internal Revenue Code specifies that interest paid or accrued on "indebtedness incurred or continued to purchase or carry obligations, the interest on which is wholly exempt from taxes," is not tax deductible. It does not make any difference if any tax-exempt interest is actually received by the taxpayer in the taxable year. In other words, interest is not deductible on funds borrowed to purchase or carry tax-exempt securities.

Special rules apply to commercial banks. At one time, banks were permitted to deduct all the interest expense incurred to purchase or carry municipal securities. Tax legislation subsequently limited the deduction first to 85% of the interest expense and then to 80%. The 1986 tax law eliminated the deductibility of the interest expense for bonds acquired after August 6, 1986. The exception to this nondeductibility of interest expense rule is for bank-qualified issues. These are tax-exempt obligations sold by small issuers after August 6, 1986 and purchased by the bank for its investment portfolio.

An issue is bank qualified if (1) it is a tax-exempt issue other than private activity bonds, but including any bonds issued by 501(c)3 organizations, and (2) it is designated by the issuer as bank qualified and the issuer or its subordinate entities reasonably do not intend to issue more than $10 million of such bonds. A nationally recognized and experienced bond attorney should include in the opinion letter for the specific bond issue that the bonds are bank qualified.

Municipal securities are issued for various purposes. Short-term notes typically are sold in anticipation of the receipt of funds from taxes or receipt of proceeds from the sale of a bond issue, for example. Proceeds from the sale of short-term notes permit the issuing municipality to cover seasonal and temporary imbalances between outlays for expenditures and inflows from taxes. Municipalities issue long-term bonds as the principal means for financing both (1) long-term capital projects such as schools, bridges, roads, and airports; and (2) long-term budget deficits that arise from current operations.

An official statement describing the issue and the issuer is prepared for new offerings. Municipal securities have legal opinions that are summarized in the official statement. The importance of the legal opinion is twofold. First, bond counsel determines if the issue is indeed legally able to issue the securities. Second, bond counsel verifies that the issuer has properly prepared for the bond sale by having enacted various required ordinances, resolutions, and trust indentures and without violating any other laws and regulations.

There are basically two types of municipal security structures: tax-backed debt and revenue bonds. We describe each type, as well as variants.

Tax-backed debt obligations are secured by some form of tax revenue. The broadest type of tax-backed debt obligation is the general obligation debt. Other types that fall into the category of tax-backed debt are appropriation-backed obligations, debt obligations supported by public credit enhancement programs, and short-term debt instruments.

General Obligation Debt

General obligation pledges include unlimited and limited tax general obligation debt. The stronger form is the unlimited tax general obligation debt (also called an ad valorem property tax debt) because it is secured by the issuer's unlimited taxing power (corporate and individual income taxes, sales taxes, and property taxes) and is said to be secured by the full faith and credit of the issuer. A limited tax general obligation debt (also called a limited ad valorem tax debt) is a limited tax pledge because for such debt there is a statutory ceiling on the tax rates that may be levied to service the issuer's debt.

There are general obligation bonds that are secured not only by the issuer's general taxing powers to create revenues accumulated in a general fund, but also secured by designated fees, grants, and special charges from outside the general fund. Due to the dual nature of the revenue sources, bonds with this security feature are referred to as double-barreled in security. As an example, special purpose service systems issue bonds that are secured by a pledge of property taxes, a pledge of special fees/operating revenue from the service provided, or a pledge of both property taxes and special fees/operating revenues.

Appropriation-Backed Obligations

Bond issues of some agencies or authorities carry a potential state liability for making up shortfalls in the issuing entity's obligation. While the appropriation of funds must be approved by the issuer's state legislature, and hence they are referred to as appropriation-backed obligations, the state's pledge is not binding. Because of this nonbinding pledge of tax revenue, such issues are referred to as moral obligation bonds. An example of the legal language describing the procedure for a moral obligation bond that is enacted into legislation is as follows:

In order to further assure the maintenance of each such debt reserve fund, there shall be annually apportioned and paid to the agency for deposit in each debt reserve fund such sum, if any, as shall be certified by the chairman of the agency to the governor and director of the budget as necessary to restore such reserve fund to an amount equal to the debt reserve fund requirement. The chairman of the agency shall annually, on or before December 1, make and deliver to the governor and director of the budget his certificate stating the sum or sums, if any, required to restore each such debt reserve fund to the amount aforesaid, and the sum so certified, if any, shall be apportioned and paid to the agency during the then current state fiscal year.

The reason for the moral obligation pledge is to enhance the creditworthiness of the issuing entity. The first moral obligation bond was issued by the Housing Finance Agency of the state of New York. Historically, most moral obligation debt has been self-supporting; that is, it has not been necessary for the state of the issuing entity to make an appropriation. In those cases in which state legislatures have been called on to make an appropriation, they have. For example, the states of New York and Pennsylvania did this for bonds issued by their Housing Finance Agency; the state of New Jersey did this for bonds issued by the Southern Jersey Port Authority.

Another type of appropriation-backed obligation is lease-backed debt. There are two types of leases. One type is basically a secured long-term loan disguised as lease. The "leased" asset is the security for the loan. In the case of a bankruptcy, the court would probably rule such an obligation as the property of the user of the leased asset and the debt obligation of the user. In contrast, the second type of lease is a true lease in which the user of the leased asset (called the lessee) makes periodic payments to the leased asset's owner (called the lessor) for the right to use the leased asset. For true leases, there must be an annual appropriation by the municipality to continue making the lease payments.

Dedicated Tax-Backed Obligations

States and local governments have issued increasing amounts of bonds where the debt service is to be paid from so-called dedicated revenues such as sales taxes, tobacco settlement payments, fees, and penalty payments. Many are structured to mimic asset-backed securities.

Let's look at one type of such security. Tobacco settlement revenue (TSR) bonds are backed by the tobacco settlement payments owed to the state or local entity resulting from the master settlement agreement between most of the states and the four major U.S. tobacco companies (Philip Morris Inc., R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., Lorillard Tobacco Co., and Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp.) in November 1998. The states that are parties to the settlement have subsequent to the settlement issued $36.5 billion of tax-exempt revenue bonds. There are unique risks associated with TSR bonds having to do with structural risk, the credit risk of the four tobacco companies, cash flow risk, and litigation risk. (These risks are discussed in Lian [2008] and Ellis [2008].) The initial credit ratings when these bonds were first issued was typically within the A or AA range; however, by mid-2007, their credit ratings were generally in the BBB range, reflecting these risks.

Debt Obligations Supported by Public Credit Enhancement Programs

Unlike a moral obligation bond, there are bonds that carry some form of public credit enhancement that is legally enforceable. This occurs when there is a guarantee by the state or a federal agency or when there is an obligation to automatically withhold and deploy state aid to pay any defaulted debt service by the issuing entity. It is the latter form of public credit enhancement that is employed for debt obligations of a state's school systems.

Short-Term Debt Instruments

Short-term debt instruments issued by municipalities include notes, commercial paper, variable-rate demand obligations, and a hybrid of the last two products.

Municipal Notes Usually, municipal notes are issued for a period of 12 months, although it is not uncommon for such notes to be issued for periods as short as 3 months and for as long as 3 years. Municipal notes include bond anticipation notes (BANs) and cash flow notes. BANs are issued in anticipation of the sale of long term bonds. The issuing entity must obtain funds in the capital market to pay off the obligation.

Cash flow notes include tax anticipation notes (TANs) and revenue anticipation notes (RANs). TANs and RANs (also known as TRANs) are issued in anticipation of the collection of taxes or other expected revenues. These are borrowings to even out irregular flows into the treasury of the issuing entity. The pledge for cash flow notes can be either a broad general obligation pledge of the issuer or a pledge from a specific revenue source. The lien position of cash flow noteholders relative to other general obligation debt that has been pledged the same revenue can be either (1) a first lien on all pledged revenue, thereby having priority over general obligation debt that has been pledged the same revenue, (2) a lien that is in parity with general obligation debt that has been pledged the same revenue, or (3) a lien that is subordinate to the lien of general obligation debt that has been pledged the same revenue.

Commercial Paper Commercial paper is also used by municipalities to raise funds on a short-term basis ranging from 1 day to 270 days. There are two types of commercial paper issued, unenhanced and enhanced. Unenhanced commercial paper is a debt obligation issued based solely on the issuer's credit quality and liquidity capability.

Enhanced commercial paper is a debt obligation that is credit enhanced with bank liquidity facilities (e.g., a letter of credit), insurance, or a bond purchase agreement. The role of the enhancement is to reduce the risk of nonrepayment of the maturing commercial paper by providing a source of liquidity for payment of that debt in the event no other funds of the issuer are currently available.

Provisions in the 1986 tax act restricted the issuance of tax-exempt commercial paper. Specifically, the act limited the new issuance of municipal obligations that are tax exempt, and as a result, every maturity of a tax-exempt municipal issuance is considered a new debt issuance. Consequently, very limited issuance of tax-exempt commercial paper exists. Instead, issuers use one of the next two products to raise short-term funds.

Variable-Rate Demand Obligations Variable-Rate Demand Obligations (VRDOs) are floating-rate obligations that have a nominal long-term maturity but have a coupon rate that is reset either daily or every 7 days. The investor has an option to put the issue back to the trustee at any time with 7 days notice. The put price is par plus accrued interest. There are unenhanced and enhanced VRDOs.

Commercial Paper/VRDO Hybrid The commercial paper/VRDO hybrid is a product that is customized to meet the investor's cash flow needs. There is flexibility in structuring the maturity as with commercial paper because there is a remarketing agent who establishes interest rates for a range of maturities. While there may be a long stated maturity for such issues, they contain a put provision as with a VRDO. The range of the put period can be from 1 day to more than 360 days. On the put date, the investor has two choices. The first is to put the bonds to the issuer; by doing so, the investor receives principal and interest. The second choice available to the investor is to extend the maturity at the new interest rate and put date posted by the remarketing agent at that time.

Revenue bonds are the second basic type of security structure found in the municipal bond market. These bonds are issued for enterprise financings that are secured by the revenues generated by the completed projects themselves, or for general public-purpose financings in which the issuers pledge to the bondholders the tax and revenue resources that were previously part of the general fund. This latter type of revenue bond is usually created to allow issuers to raise debt outside general obligation debt limits and without voter approval.

The trust indenture for a municipal revenue bond details how revenue received by the enterprise will be distributed. This is referred to as the flow-of-funds structure. In a typical revenue bond, the revenue is first distributed into a revenue fund. It is from that fund that disbursements for expenses are made. The typical flow-of-fund structure provides for payments in the following order into other funds: operation and maintenance fund, sinking fund, debt service reserve fund, renewal and replacement fund, reserve maintenance fund, and surplus fund.

Revenue bonds can be classified by the type of financing. These include utility revenue bonds, transportation revenue bonds, housing revenue bonds, higher education revenue bonds, health care revenue bonds, seaport revenue bonds, sports complex and convention center revenue bonds, and industrial development revenue bonds. We discuss these revenue bonds as follows. Revenue bonds are also issued by Section 501(c)3 entities (museums and foundations).

Utility Revenue Bonds

Utility revenue bonds include water, sewer, and electric revenue bonds. Water revenue bonds are issued to finance the construction of water treatment plants, pumping stations, collection facilities, and distribution systems. Revenues usually come from connection fees and charges paid by the users of the water systems. Electric utility revenue bonds are secured by revenues produced from electrical operating plants. Some bonds are for a single issuer who constructs and operates power plants and then sells the electricity. Other electric utility revenue bonds are issued by groups of public and private investor-owned utilities for the joint financing of the construction of one or more power plants.

Also included as part of utility revenue bonds are resource recovery revenue bonds. A resource recovery facility converts refuse (solid waste) into commercially saleable energy, recoverable products, and residue to be landfilled. The major revenues securing these bonds usually are (1) fees paid by those who deliver the waste to the facility for disposal, (2) revenues from steam, electricity, or refuse-derived fuel sold to either an electric power company or another energy user, and (3) revenues from the sale of recoverable materials such as aluminum and steel scrap.

Transportation Revenue Bonds

Included in the category of transportation revenue bonds are toll road revenue bonds, highway user tax revenue bonds, airport revenue bonds, and mass transit bonds secured by fare-box revenues. For toll road revenue bonds, bond proceeds are used to build specific revenue-producing facilities such as toll roads, bridges, and tunnels. The pledged revenues are the monies collected through tolls. For highway-user tax revenue bonds, the bondholders are paid by earmarked revenues outside of toll collections, such as gasoline taxes, automobile registration payments, and driver's license fees. The revenues securing airport revenue bonds usually come from either traffic-generated sources—such as landing fees, concession fees, and airline fueling fees—or lease revenues from one or more airlines for the use of a specific facility such as a terminal or hangar. Muller (2008) provides a discussion of how to analyze toll road bonds. The analysis of airport revenue bonds is provided by Oliver and Clements (2008); case studies of airport revenue bonds are provided by Spiotto (2008) and Oliver (2008).

Housing Revenue Bonds

There are two types of housing revenue bonds: single-family mortgage revenue bonds and multifamily housing revenue bonds.

Single-family revenue bonds are issued by state and local housing finance agencies in order to obtain funds to assist low- to middle-income individuals purchase their first home. This assistance is accomplished by using the proceeds from the bond sale to acquire the newly originated mortgages and pooling them. More specifically, the loans are l-to-4-single-family home, 30-year fixed-rate mortgages. While the primary source of repayment for these bonds are the mortgage payments on the pool of loans, there are several other layers of credit protection. These include (1) overcollateralization of the loan pool (that is, from 102% to as much as 110% of the bonds outstanding), (2) for loans in the pool with a loan-to-value ratio of 80% or greater, primary mortgage insurance is required (either Federal Housing Administration or Veteran's Administration or private mortgage insurance with a rating of at least double A), and (3) the housing finance agency of many states will provide their general obligation pledge. (See Van Kuller [2008a] for more details on these credit enhancements as well as how to analyze single-family bonds.)

As with mortgage-backed securities issued in the taxable sector, investors in single-family mortgage revenue bonds are exposed to prepayment risk. (See Chapter 32 of Volume I.) This is the risk that borrowers in the mortgage pool will prepay their loans when interest rates decline below their loan rate. The disadvantage to the investor is twofold. First, the proceeds received from the prepayments must be reinvested at a lower rate. Second, a property of bonds with prepayment or call options is that their price performance is adversely affected when interest rates decline compared to noncallable bonds.

Multifamily revenue bonds are usually issued for a variety of housing projects involving tenants who qualify as low-income families and senior citizens. There are various forms of credit enhancement for these bonds. Some of these are what is found in commercial mortgage-backed securities where the underling is multifamily housing: overcollateralization, senior-subordinated structure, private and agency mortgage insurance (state insurance for some issues), bank letters of credit, and cross-collateralization and cross default provisions in pools. In addition, there may be credit enhancement in the form of moral obligations or an appropriation obligation of the state or city issuing the bonds. Van Kuller (2008b) explains the structures of multifamily housing revenue bonds and to analyze their credit risk.

Higher Education Revenue Bonds

There are two types of higher education revenue bonds: college and university revenue bonds and student loan revenue bonds. The revenues securing public and private college and university revenue bonds usually include dormitory room rental fees, tuition payments, and sometimes the general assets of the college or university. For student loan revenue bonds, the structures are very similar to what is found in the student loan sector of the taxable asset-backed securities market. For a discussion of how to analyze the credit risk of higher education revenue bonds, see Mincke (2008).

Health Care Revenue Bonds

Health care revenue bonds are issued by private, not-for-profit hospitals (including rehabilitation centers, children's hospitals, and psychiatric institutions) and other health care providers such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs), continuing care retirement communities and nursing homes, cancer centers, university faculty practice plans, and medical specialty practices. The revenue for health care revenue bonds usually depends on federal and state reimbursement programs (such as Med-icaid and Medicare), third-party commercial payers (such as Blue Cross, HMOs, and private insurance), and individual patient payments. Cavallaro (2008) explains how to analyze hospital revenue bonds.

Seaport Revenue Bonds

The security for seaport revenue bonds can include specific lease agreements with the benefiting companies or pledged marine terminal and cargo tonnage fees.

Some municipal securities have special security structures. These include insured bonds, bank-backed municipal bonds, and refunded bonds. We describe these three special security structures as follows.

Insured Bonds

Municipal bonds can be credit enhanced by an unconditional guarantee of a commercial insurance company. The insurance cannot be canceled and typically is in place for the term of the bond. The insurance provides for the insurance company writing the policy to make payments to the bondholders of any principal and/or coupon interest that is due on a stated maturity date but that has not been paid by the bond issuer. The insurer's payment is not an advance of the payments due by the issuer but is rather made according to the original repayment schedule obligation of the issuer.

As of 2007, it has been estimated that there were almost $600 billion of insured municipal bonds outstanding and that more than 50% of newly issued municipal bonds were insured (Cirillo, 2008). The track record on municipal bonds is unblemished. Since the first introduction of municipal bond insurance in 1971, no insurer has failed to make payments on any insured municipal bond as of year end 2007. That said, as of early 2008, the major bond insurers faced potential downgrading because of their commitments in the subprime mortgage market.

The insurers of municipal bonds are typically monoline insurance companies that are primarily in the business of providing guarantees. They include the following triple-A-rated monoline insurers as of year end 2007: Ambac Assurance Corp. (AMBAC or Ambac), Assured Guaranty Corp., CIFG Financial Guaranty, Financial Guaranty Insurance Corp. (FGIC), Financial Security Assurance Inc. (FSA), MBIA Insurance Corp. (MBIA), and XL Capital Assurance, Inc. (XL). These are the same insurance companies that provide an insurance wrap for asset-backed securities. There are lower-rated insurers, and they are used by some municipalities when a rating below triple A is sought. These monoline insurers include Radian Asset Insurance, Inc. and ACA Financial Guaranty, double A and single A rated insurers, respectively, as of year end 2007.

Not all bonds in a series issued by a municipality may be covered by insurance. The cover of the official statement must clearly identify which bonds in the series are insured. If there are both insured and non-insured bonds in a series, that must clearly be disclosed in the official statement. In addition, the name of the bond insurer(s) must be clearly shown on the cover of the official statement.

Bonds trading in the secondary market that do not carry insurance can be insured through a personalized insurance policy for a negotiated premium. The insured bond lot only will continue to carry the insurance. An investor can check if a bond lot is insured by contacting the secondary market desk of an insurer. Closed-end funds and unit investment trusts can obtain insurance for a group of bonds. However, once these entities sell the insured bonds, the insurance does not carry over to the new owner.

By obtaining municipal bond insurance, the issuer obviously reduces the credit risk for the investor. Typically, it is bonds issued by smaller governmental units that are not widely known in the financial community, bonds that have a sound though complex and confusing security structure, and bonds issued by infrequent local-government borrowers that do not have a general market following among investors that find it advantageous to obtain municipal bond insurance. Cirillo (2008) provides a more thorough discussion of issuers of insuring bonds.

It should be noted that the credit quality considerations of bond insurers in evaluating whether to insure an issue are more stringent than that used by rating agencies when assigning a rating to an issue. The reason is simple: The bond insurer is making a commitment for the life of the issue. Rating agencies only assign a rating that would be expected to be downgraded in the future if there is credit deterioration of the issuer. Put simply, rating agencies can change a rating but bond insurers cannot change their obligation. Consequently, bond insurers typically insure bonds that would have received an investment-grade rating (at least triple B) in the absence of any insurance.

Bank-Backed Bonds

Municipal issuers have increasingly used various types of facilities provided by commercial banks to credit enhance and thereby improve the marketability of issues. There are three basic types of bank support: letter of credit, irrevocable line of credit, and revolving line of credit.

A letter of credit (LOC) is the strongest type of support available from a commercial bank. The parties to a LOC agreement are (1) the bank that issues the LOC (that is, the LOC issuer), (2) the municipal issuer who is requesting the LOC in connection with a security (the LOC-backed bonds), and (3) the LOC beneficiary who is typically the trustee. The municipal issuer is obligated to reimburse the LOC issuer for any funds it draws down under the agreement.

There are two types of LOCs: direct-pay LOC and standby LOC. With a direct-pay LOC, typically the issuer is entitled to draw upon the LOC in order to make interest and principal payment if a certain event occurs. The LOC beneficiary receives payments from the LOC issuer with the trustee having to request a payment. In contrast, with a standby LOC, the LOC beneficiary typically can only draw down on the agreement if the municipal issuer fails to make interest and/principal payments at the contractual due date. The LOC beneficiary must first request payment from the municipal issuer before drawing upon the LOC. When a LOC is issued by a smaller local bank, there may be a second LOC in place issued by a large national bank. This type of LOC is called a confirming LOC and is drawn upon only if the primary LOC issuer (the smaller local bank) fails to pay a draw request. For a further discussion of LOCs, see Zerega (2008).

An irrevocable line of credit is not a guarantee of the bond issue, though it does provide a level of security. A revolving line of credit is a liquidity-type credit facility that provides a source of liquidity for payment of maturing debt in the event no other funds of the issuer are currently available. Because a bank can cancel a revolving line of credit without notice if the issuer fails to meet certain covenants, bond security depends entirely on the creditworthiness of the municipal issuer.

Refunded Bonds

Municipal bonds are sometimes refunded. An issuer may refund a bond issue for the same reasons that a corporate treasurer may seek to do so: (1) reducing funding costs after taking into account the costs of refunding, (2) eliminating burdensome restrictive covenants, and (3) altering the debt maturity structure for budgetary reasons.

Often, a refunding takes place when the original bond issue is escrowed or collateralized by direct obligations guaranteed by the U.S. government. By this it is meant that a portfolio of securities guaranteed by the U.S. government are placed in a trust. The portfolio of securities is assembled such that the cash flows from the securities match the obligations that the issuer must pay. For example, suppose that a municipality has a 5% $200 million issue with 15 years remaining to maturity. The bond obligation therefore calls for the issuer to make payments of $5 million every 6 months for the next 15 years and $200 million 15 years from now. If the issuer wants to refund this issue, a portfolio of U.S. government obligations can be purchased that has a cash flow that matches that liability structure: $5 million every 6 months for the next 15 years and $200 million 15 years from now.

Once this portfolio of securities whose cash flows match those of the municipality's obligation is in place, the refunded bonds are no longer general obligation or revenue bonds. Instead, the issue is supported by the cash flows from the portfolio of securities held in an escrow fund. Such bonds, if escrowed with securities guaranteed by the U.S. government, have little, if any, credit risk and are therefore the safest municipal bonds available.

The escrow fund for a refunded municipal bond can be structured so that the refunded bonds are to be called at the first possible call date or a subsequent call date established in the original bond indenture. Such bonds are known as prerefunded municipal bonds. While refunded bonds are usually retired at their first or subsequent call date, some are structured to match the debt obligation to the retirement date. Such bonds are known as escrowed-to-maturity bonds. For a further discussion of refunded municipal bonds, see Feldstein (2008).

Interest rates on municipal bonds reflect not only the risks associated with corporate bonds but also reflect the tax advantage of tax-exempt municipal bonds, including the impact of the AMT and state and local tax treatment. A commonly used yield measure when comparing the yield on a tax-exempt municipal bond with a comparable taxable bond is the equivalent taxable yield and is computed as follows:

The equivalent taxable yield shows the approximate yield that an investor would have to earn on a taxable bond in order to realize the same yield after taxes.

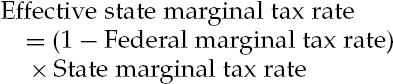

The effective marginal tax rate must take into account both the exemption of interest income from federal income taxes and the effective tax rate applied at the state level if one applies. In computing the effective state marginal tax rate, consideration is given to the deductibility of state taxes for determining federal income taxes. To do so, the following formula can be used to calculate the effective state marginal tax rate:

For example, in 2007 the Pennsylvania tax rate was flat at 3.07% for a taxpayer who does not reside in the city of Philadelphia. Thus, the state marginal tax rate is 3.07%. Assuming an investor is faces a 35% federal marginal tax rate, then the effective state marginal tax rate is

In a state that does not tax municipal interest from either in-state or out-of-state issuers, the state marginal tax rate is obviously zero. In comparing the yield offered on in-state and out-of-state issuers, this adjustment is important.

The federal marginal tax rate in the above formula is the benefit received from being able to deduct state taxes in determining federal income taxes. For investors who do not itemize deductions or whose income is such that state tax deductions have minimal value, the federal marginal tax rate has a benefit is zero and the effective state marginal tax rate is therefore the state marginal tax rate.

The effective marginal tax rate that is used in the formula for the equivalent taxable yield is then the sum of the federal marginal tax rate plus the effective state marginal tax rate. In our example, an investor facing a 35% federal marginal tax rate and an effective state marginal tax rate of 2% would have an effective marginal tax rate of 37%. Suppose, for example, a yield on a municipal bond being considered for acquisition is 6%. Then the equivalent taxable yield is 5%/(l −0.37) = 0.794 or 7.94%.

A convention in the bond market is to quote yields on municipal bonds relative to some benchmark taxable bond yield such as a comparable maturity Treasury security or as a percentage of the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) from the swap yield curve. This ratio is referred to as the yield ratio, and it is normally less than 100% because municipal bonds offer a yield that is less than the yield on a comparable taxable bond.

As in the taxable bond market, municipal bonds may have a fixed or floating interest rate. There are two types of floating-rate municipal bonds. The first has the traditional floating-rate formula that calls for the resetting of the issue's coupon rate based on a reference rate plus a quoted margin. The quoted margin is fixed over the life of the bond issue. In the corporate bond market, the reference rate is typically a Treasury rate or some short-term money market rate or swap. In the municipal bond market, the reference rate is typically some percentage of a taxable reference rate (e.g., 75% of six-month LIBOR) or a standard industry reference rate such as the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA) Municipal Swap Index (formerly The Bond Market Association/PSA Municipal Swap Index). The index, created by the Municipal Market Data, serves as the reference rate in a municipal swap and is calculated weekly.

The other type of floating-rate municipal bond is an inverse floating-rate bond or inverse floater. As the name suggests, for an inverse floater the coupon rate changes in the opposite direction of the change in interest rates. That is, if interest rates increase (decrease) since the previous reset of the coupon rate, the new coupon rate decreases (increase). Inverse floaters in the municipal market are created by a sponsor who deposits a fixed-rate municipal security into a trust. The trust then creates two classes of floating-rate securities. The first is a short-term floating-rate security. This floating-rate security can be tendered for redemption at par value on specified dates (typically every week) and are referred to as tender option bonds (TOBs). The interest on the TOBs is determined through an auction process that is conducted by a remarketing agent. The second bond class created is the inverse floater. The interest paid to this bond class is the residual interest from the fixed-rate municipal bonds placed in the trust after paying the floating-rate security bondholders and the expenses of the trust. For this reason, the inverse floater is sometimes called the residual. When reference rates rise (fall) and the floating-rate security receives a greater (lesser) share of the interest from the fixed-rate municipal security in the trust, the inverse floater investor receives less (more) interest. The holders of the inverse floater have the option to collapse the trust. They can do so by requiring the trustee to pay off the floating-rate securities outstanding and instructing the trustee to give them the fixed-rate securities placed in the trust.

Investors in municipal bonds face the typical risk associated with investing in bonds: credit risk, interest rate risk, call risk, and liquidity risk.

Credit risk includes credit default risk, credit spread risk, and downgrade risk. Credit default risk is gauged by the ratings assigned by Moody's, Standard & Poor's, and Fitch. Interest rate risk is typically measured by the duration of a bond: the approximate percentage price change of a bond for a 100-basis-point change in interest rates. Call risk arises for callable bonds and the adverse consequences associated when interest rates decline were mentioned earlier in this chapter. An investor in single-family housing revenue bonds is exposed to a form of call risk, prepayment risk.

There are two risks that are to some extent unique to investors in the municipal bond market. The first is structure risk. This is the risk that the security structure may be legally challenged. This may arise in new structures, with the best example being the Washington Public Supply System (WPPS) bonds in the 1980s.

The second risk is tax risk. This risk comes in two forms. The first is the risk that the federal income tax rate will be reduced. To understand this risk, note that in the formula for the equivalent taxable yield, the yield is lower the smaller the effective marginal tax rate. A reduction in the effective marginal tax rate therefore reduces the equivalent taxable yield and so that the yield on municipal bonds can stay competitive with taxable bonds, the price of municipal bonds will decline. The second type of tax risk is related to legal risk. The Internal Revenue Service may declare a bond issued as a tax-exempt as taxable. This may be the result of the issuer not complying with IRS regulations. A loss of the tax-exemption feature will cause the municipal bond to decline in value in order to provide a yield comparable to similar taxable bonds.

Municipal securities are issued by state and local governments as well as authorities created by them. While there are both tax-exempt and taxable municipal securities, the market is dominated by the former. Tax exemption refers to the exemption of interest income from taxation at the federal level. Because of the importance of the tax advantage, investors must be aware of federal income tax provisions affecting municipal securities: treatment of original-issue discount, alternative minimum tax rules, and deductibility of interest in acquiring municipal securities with borrowed funds. The treatment of interest income at the state and local levels varies.

There are basically two types of municipal security structures: tax-backed debt and revenue bonds. There are also municipal bonds with special structures (insured bonds, bank-backed bonds, and refunded bonds).

Because of their tax advantage, yields offered on municipal bonds are normally less than that on comparable taxable bonds. To compare a tax-exempt municipal bond's yield with that of a taxable bond, the equivalent taxable yield can be computed. This yield depends on the investor's effective marginal tax rate. The effective marginal tax rate depends on the investor's federal marginal tax rate and effective state marginal tax rate.

Municipal bonds expose investors to the usual risks associated with bond investing—credit risk, interest rate risk, call risk, and liquidity risk—as well as some unique risks—structure risk and tax risk.

Cavallaro, L. (2008). Hospital bond analysis. In S. G. Feld-stein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 845-858), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Cirillo, D. K. (2008). How to analyze the municipal bond insurers and the bonds they insure. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 1085-1099), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Feldstein, S. G. (2008). How to analyze refunded municipal bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 1035-1038), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ellis, G. (2008). Analysis of tobacco revenue settlement bonds: Assessing cigarette consumption decline estimates. Journal of Structured Finance (Winter): 60-79.

Garrett, D. J. (2008). Discovering relative value using custom indices. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 571-575), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Lian, G. (2008). How to analyze tobacco bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 957-978), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Maco, P. S., and Taffe, J. W (2008). The Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 383-396), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Mincke, B. (2008). How to analyze higher education bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 1055-1075), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Muller, R. H. (2008). Toll road analysis. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 981-993), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Oliver, W E. (2008). Aruba Airport Authority airport revenue bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 1127-1133), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Oliver, W E., and Clements, D. (2008). How to analyze airport revenue bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (Eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 813-818), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Peng, J., and Brucato, P. Jr. (2001). Do competitive-only laws have an impact on the borrowing cost of municipal bonds? Municipal Finance Journal 22: 61-76.

Peng, J., Kriz, K. A., and Neish, T. (2008). In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 51-66), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Spiotto, J. E. (2008). Tax-exempt airport finance: Tales from the friendly skies. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 1165-1184), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Van Kuller (2008a). Single-family housing bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 861-891), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Van Kuller (2008b). Multifamily housing bonds. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 893-921), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Zerega, T. (2008). The use of letters-of-credit in connection with municipal securities. In S. G. Feldstein and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), The Handbook of Municipal Bonds (pp. 1015-1023), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.