FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

LAURIE S. GOODMAN, PhD

Co-head of Global Fixed Income Research and Manager of U.S. Securitized Products Research, UBS

DOUGLAS J. LUCAS

Executive Director and Head of CDO Research, UBS

Abstract: Asset-backed securities are debt instruments that are backed by a pool of loans or receivables. There is considerable diversity in the types of assets that have been securitized. These assets can be classified as mortgage assets and nonmortgage assets. The former includes residential and commercial mortgage loans. The two largest types of nonmortgage assets that have been securitized are card receivables and auto loan receivables. Investors are attracted to asset-backed securities primarily because of their desirable investment and maturity characteristics.

Keywords: securitization, asset-backed securities (ABSs), credit card receivable-backed securities, monthly mortgage payment, early amortization trigger, auto loan-backed securities, prepayments, absolute prepayment speed, single monthly mortality rate, student loan asset-backed securities (SLABS), alternative loans, Small Business Administration (SBA) loan-backed securities, aircraft lease-backed securities, franchise loan-backed securities, loan-to-value ratio, fixed charge coverage ratio, rate reduction bonds (RRBs), stranded costs, stranded assets, competitive transition charge (CTC)

The process for the creation of asset-backed securities (ABSs), referred to as securitization, is as follows. The owner of assets sells a pool of assets to a bankruptcy remote vehicle called a special purpose entity (SPE). The SPE obtains the proceeds to acquire the asset pool, referred to as the collateral, by issuing debt instruments. The cash flow of the asset pool is used to satisfy the obligations of the debt instruments issued by the SPE. The debt instruments issued by the SPE are referred to generically as asset-backed securities, asset-backed notes, asset-backed bonds, or asset-backed obligations.

ABSs issued in a single securitization can have different credit exposure and based on the credit priority, securities are described as senior notes and junior notes (subordinated notes). In the prospectus for a securitization, the securities are actually referred to as certificates: pass-through certificates or pay-through certificates. The distinction between these two types of certificates is the nature of the claim that the investor has on the cash flow generated by the asset pool. If the investor has a direct claim on all of the cash flow and the certificate holder has a proportionate share of the collateral's cash flow, the term "pass-through certificate" (or "beneficial interest certificate") is used. When there are rules that are used to allocate the collateral's cash flow among different classes of investors, the asset-backed securities are referred to as pay-through certificates.

The types of assets that have been securitized are generally classified as traditional assets and nontraditional or emerging assets. Market participants attribute different meaning as to what is meant by nontraditional assets. Some refer to nontraditional assets as assets other than the major types of assets that have been securitized at the time. In the early years of the ABS market, traditional assets included home equity loans, manufactured housing loans, credit card loans, and auto loans. The list of what is viewed as traditional assets has changed as securitization has become a more popular vehicle for issuers to raise funds. Others view nontraditional or emerging assets in a more limited way: those assets that are being securitized for the first time or for which there have been very few securitizations. For example, the recording artists David Bowie, James Brown, the Isley Brothers, and Rod Stewart have securitized their future music royalties, the first being by Bowie, who in 1997 issued $55 million of ABS backed by the current and future revenues of his first 25 music albums (287 songs) recorded prior to 1990. (These bonds, popularly referred to as "Bowie bonds," were purchased by Prudential Insurance Company and had a maturity of 10 years. When the bonds matured in 2007, the royalty rights reverted back to David Bowie.)

Another classification of ABS is based on whether the assets are mortgage-related assets or nonmortgage-related assets. The former includes residential mortgage loans such as home equity loans and manufactured housing; the latter includes a wide range consumer and business loans and receivables, as well as the securitization of whole businesses. In this chapter, we will discuss ABSs for which the collateral is a pool of traditional nonmort-gage assets. More specifically, we will describe credit card receivable-backed securities, auto loan-backed securities, student loan-backed securities, Small Business Administration (SBA) loan-backed securities, aircraft lease-backed securities, franchise loan-backed securities, and rate reduction bonds. For a description of the structure of ABS in general, see Chapter 73 and Chapter 74 of Volume III.

A major sector of the ABS market is that of securities backed by credit card receivables. Credit cards are issued by banks (e.g., Visa and MasterCard), retailers (e.g., JCPenney and Sears), and travel and entertainment companies (e.g., American Express). Credit card deals are structured as either a discrete trust or master trust. With a master trust the issuer can sell several series from the same trust.

For a pool of credit card receivables, the cash flow consists of finance charges collected, fees, and principal. Finance charges collected represent the periodic interest the credit card borrower is charged based on the unpaid balance after the grace period. Fees include late payment fees and any annual membership fees.

Interest to security holders is paid periodically (e.g., monthly, quarterly, or semiannually). The interest rate may be fixed or floating. The floating rate is uncapped.

A credit card receivable-backed security is a nonamortizing security. For a specified period of time, referred to as the lockout period or revolving period, the principal payments made by credit card borrowers comprising the pool are retained by the trustee and reinvested in additional receivables to maintain the size of the pool. The lockout period can vary from 18 months to 10 years. So, during the lockout period, the cash flow that is paid out to security holders is based on finance charges collected and fees.

After the lockout period, the principal is no longer reinvested but paid to investors. This period is referred to as the principal-amortization period, and the various types of structures are described later.

Several concepts must be understood in order to assess the performance of the portfolio of receivables and the ability of the issuer to meet its interest obligation and repay principal as scheduled.

The gross yield includes finance charges collected and fees. Charge offs represent the accounts charged off as uncollectible. Net portfolio yield is equal to gross portfolio yield minus charge-offs. The net portfolio yield is important because it is from this yield that the bondholders will be paid. So, for example, if the average yield (WAC) that must be paid to the various tranches in the structure is 5% and the net portfolio yield for the month is only 4.5%, there is the risk that the bondholder obligations will not be satisfied.

Delinquencies are the percentages of receivables that are past due for a specified number of months, usually 30, 60, and 90 days. They are considered an indicator of potential future charge-offs.

The monthly payment rate (MPR) expresses the monthly payment (which includes finance charges, fees, and any principal repayment) of a credit card receivable portfolio as a percentage of credit card debt outstanding in the previous month. For example, suppose a $500 million credit card receivable portfolio in January realized $50 million of payments in February. The MPR would then be 10% ($50 million divided by $500 million).

There are two reasons why the MPR is important. First, if the MPR reaches an extremely low level, there is a chance that there will be extension risk with respect to the principal payments on the bonds. Second, if the MPR is very low, then there is a chance that there will not be sufficient cash flows to pay off principal. This is one of the events that could trigger early amortization of the principal (described as follows).

At issuance, portfolio yield, charge-offs, delinquency, and MPR information are provided in the prospectus. Information about portfolio performance is thereafter available from various sources.

There are provisions in credit card receivable-backed securities that require early amortization of the principal if certain events occur. Such provisions, which are referred to as either early amortization or rapid amortization, are included to safeguard the credit quality of the issue. The only way that principal cash flows can be altered is by triggering the early amortization provision.

Typically, early amortization allows for the rapid return of principal in the event that the three-month average excess spread earned on the receivables falls to zero or less. When early amortization occurs, the credit card tranches are retired sequentially (that is, first the AAA bond, then the AA rated bond, and so on). This is accomplished by paying the principal payments made by the credit card borrowers to the investors instead of using them to purchase more receivables. The length of time until the return of principal is largely a function of the monthly payment rate. For example, suppose that a AAA tranche is 82% of the overall deal. If the monthly payment rate is 11%, then the AAA tranche would return principal over a 7.5-month period (82%/ll%). An 18% monthly payment rate would return principal over a 4.5-month period (82%/18%).

Monthly information is available on each deal's trigger formula and base rate. The trigger formula is the formula that shows the condition under which the rapid amortization will be triggered. The base rate is the minimum payment rate that a trust must be able to maintain to avoid early amortization.

Auto loan-backed securities are issued by:

The financial subsidiaries of auto manufacturers (domestic and foreign).

Commercial banks.

Independent finance companies and small financial institutions specializing in auto loans.

In terms of credit, borrowers are classified as either prime, nonprime, or subprime. Each originator employs its own criteria for classifying borrowers into these three broad groups. Typically, prime borrowers are those that have had a strong credit history that is characterized by timely payment of all their debt obligations. The FICO score of prime borrowers is generally greater than 680. Nonprime borrowers have usually had a few delinquent payments. Nonprime borrowers, also called near-prime borrowers, typically have a FICO score ranging from the low 600s to the mid-600s. When a borrower has a credit history of missed or major problems with delinquent loan payments and the borrower may have previously filed for bankruptcy, the borrower is classified as subprime. The FICO score for subprime borrowers typically is less than the low 600s (Roever, 2005).

The cash flow for auto loan-backed securities consists of regularly scheduled monthly loan payments (interest and scheduled principal repayments) and any prepayments. For securities backed by auto loans, prepayments result from (see Roever, 2005):

Sales and trade-ins requiring full payoff of the loan.

Repossession and subsequent resale of the automobile.

Loss or destruction of the vehicle.

Payoff of the loan with cash to save on the interest cost.

Refinancing of the loan at a lower interest cost.

While refinancings may be a major reason for prepayments of mortgage loans, they are of minor importance for automobile loans. Moreover, the interest rates for the automobile loans underlying some deals are substantially below market rates (subvented rates) since they are offered by manufacturers as part of a sales promotion.

Prepayments for auto loan-backed securities are measured in terms of the absolute prepayment speed (ABS). The ABS is the monthly prepayment expressed as a percentage of the original collateral amount. (Note that another measure of prepayments used for other asset classes that have been securitized is the single monthly mortality rate (SMM). The SMM is a monthly prepayment rate that expresses prepayments based on the prior month's balance).

When auto ABS were first issued, the typical structure was a grantor trust that issued passthrough certificates. A major drawback with using grantor trusts in creating efficient structures is the inability to time tranche securities. That is, while an issuer can use a grantor trust to create subordinate interests and thereby issue multiple bond classes, each with a different level of priority, it could not issue multiple bond classes with the same level of priority. Nor are issuers permitted to use interest rate derivatives within a grantor trust. This led to the extensive use of the pay-through structures by issuers. The most common pay-through structure used is the owner trust.

Moreover, because of the flexibility granted to issuers to manage the cash flows from the collateral when using pay-through structures such as the owner trust, issuers could include performance-related triggers. Because of the reduced credit risk resulting from the inclusion of these triggers, issuers could reduce the cost of credit enhancement.

There are two typical structures used in auto ABS pay-through structures. In both structures there are multiple sequential-pay senior classes and a subordinate class. One of the senior classes is a Rule 2a-7 of the Investment Company Act of 1940 eligible money market class. In one typical structure, the senior classes receives all principal until every senior class is paid off. Only after that time is the subordinate class paid any principal. In the other typical structure, once the money market class is paid off, the other senior classes and the subordinate class are paid principal concurrently. However, in this structure, the concurrent payments to the senior classes and subordinate classes require that a performance trigger be reached. If the performance trigger is breached, the principal distribution rules of the second structure will be the same as that for the first structure.

Student loans are made to cover college cost (undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs such as medical school and law school) and tuition for a wide range of vocational and trade schools. Securities backed by student loans are popularly referred to as SLABS (student loan asset-backed securities).

The student loans that have been most commonly securitized are those that are made under the Federal Family Education Loan Program (FFELP). Under this program, the government makes loans to students via private lenders. The decision by private lenders to extend a loan to a student is not based on the applicant's ability to repay the loan. If a default of a loan occurs and the loan has been properly serviced, then the government will guarantee 97% of the principal and accrued interest (for loans originated in July 2006 or later).

Loans that are not part of a government guarantee program are called alternative or private loans. These loans are basically consumer loans, and the lender's decision to extend an alternative loan will be based on the ability of the applicant to repay the loan. Alternative loans are securitized in increasing amounts due to the rising cost of education.

The Student Loan Marketing Association (Sallie Mae) is a major issuer of SLABS, and its issues are viewed as the benchmark issues. Other entities that issue SLABS are either traditional for-profit issuers (e.g., the Key Corp Student Loan Trust) or nonprofit organizations (Michigan Higher Education Loan Authority and the Florida Educational Loan Marketing Corporation). The SLABS of the latter typically are issued as tax-exempt securities and therefore trade in the municipal market.

There are different types of student loans under the FFELP, including subsidized and unsubsidized Stafford loans, Parent Loans for Undergraduate Students (PLUS), and Supplemental Loans to Students (SLS). These loans involve several periods with respect to the borrower's payments—deferment period, grace period, and loan repayment period. Typically, student loans work as follows. While a student is in school, no payments are made by the student on the loan. This is the in-school deferment period. Upon leaving school, the student is extended a grace period of usually six months when no payments on the loan must be made. After this period, payments are made on the loan by the borrower (repayment period).

Prepayments typically occur due to defaults or loan consolidation. Even if there is no loss of principal faced by the investor when defaults occur, the investor is still exposed to contraction risk. This is the risk that the investor must reinvest the proceeds at a lower spread and, in the case of a bond purchased at a premium, the premium will be lost. Consolidation of a loan occurs when the student who has taken out loans over several years combines them into a single loan. The proceeds from the consolidation are distributed to the original lender and, in turn, distributed to the bondholders. Loan consolidation allows student borrowers to achieve lower rates and longer terms. Student loan consolidation was very popular during the 2001-2005 period, and lead to prepayment rates during those years that were considerably higher than anticipated when the deals were priced.

Structures on student loan floaters have experienced more than the usual amount of change since 2000. The reason for this is quite simple.

The underlying collateral—student loans—is exclusively indexed to three-month Treasury bills, while a large percentage of securities are issued as London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) floaters. This creates an inherent mismatch between the collateral and the securities.

Issuers have dealt with the mismatch in a variety of ways. Some issued Treasury bill floaters which eliminates the mismatch, others issued hedged or unhedged LIBOR floaters, while others switched back and forth between the two. More recently, some have issued both Treasury and LIBOR floaters in the same transaction. (Also in conjunction with the choice of index, issuers have incorporated a variety of basis swaps and/or have bought cap protection from third parties, while some have used internal structures to deal with the risk).

It is important to bear in mind that when an ABS structure contains a basis mismatch, it is not only the investor, but the issuer that bears a risk. Student loan deals (like deals in many other ABS classes) have excess spread; that is, roughly the difference between the net coupon on the collateral and the coupon on the bonds.

In mortgage-related ABS, the excess spread is much larger than in the student loan sector, and is used to absorb monthly losses. Because losses in federally guaranteed student loans are relatively small, the vast majority of the excess spread flows back to the issuer. Hence, the Treasury bill/LIBOR-basis risk is of major concern to issuers. When an issuer incorporates a swap in the deal, it not only reduces the risk to the investor (by eliminating the effect of an available funds cap) but reduces risk to the issuer by protecting a level of excess spread. When a cap is purchased, it is primarily for the benefit of the investor, because the cap only comes into play once the excess spread in the deal has been effectively reduced to zero.

The indices used on private and public student loan ABS transactions since the earliest deals in 1993 have changed over time (even though throughout this period, the index on the underlying loans was always three-month Treasury bills). From 1993 to 1995, most issuers, with the notable exception of Sallie Mae, used one-month LIBOR, which indicated strong investor preference for LIBOR floaters. By contrast, from Sallie Mae's first deal in late 1995, that issuer chose to issue Treasury bill floaters to minimize interest rate mismatch risk.

The Small Business Administration (SBA) is an agency of the U.S. government empowered to guarantee loans made by approved SBA lenders to qualified borrowers. The loans are backed by the full faith and credit of the government. Most SBA loans are variable rate loans where the reference rate is the prime rate. The rate on the loan is reset monthly on the first of the month or quarterly on the first of January, April, July, and October. SBA regulations specify the maximum coupon allowable in the secondary market. Newly originated loans have maturities between five and 25 years.

The Small Business Secondary Market Improvement Act passed in 1984 permitted the pooling of SBA loans. When pooled, the underlying loans must have similar terms and features. The maturities typically used for pooling loans are 7, 10, 15, 20, and 25 years. Loans without caps are not pooled with loans that have caps.

Most variable rate SBA loans make monthly payments consisting of interest and principal repayment. The amount of the monthly payment for an individual loan is determined as follows. Given the coupon formula of the prime rate plus the loan's quoted margin, the interest rate is determined for each loan. Given the interest rate, a level payment amortization schedule is determined. This level payment is paid until the coupon rate is reset.

The monthly cash flow that the investor in an SBA-backed security receives consists of:

The coupon interest based on the coupon rate set for the period.

The scheduled principal repayment (that is, scheduled amortization).

Prepayments.

Prepayments for SBA loan-backed securities are measured in terms of the conditional prepayment rate (CPR). Voluntary prepayments can be made by the borrower without any penalty. There are several factors contributing to the prepayment speed of a pool of SBA loans. A factor affecting prepayments is the maturity date of the loan. It has been found that the fastest speeds on SBA loans and pools occur for shorter maturities. The purpose of the loan also affects prepayments. There are loans for working capital purposes and loans to finance real estate construction or acquisition. It has been observed that SBA pools with maturities of 10 years or less made for working capital purposes tend to prepay at the fastest speed. In contrast, loans backed by real estate that have long maturities tend to prepay at a slow speed. All other factors constant, pools that have capped loans tend to prepay more slowly than pools of uncapped loans.

Aircraft financing has gone thorough an evolution over the past several years. It started with mainly bank financing, then moved to equipment trust certificates (ETCs), then to enhanced ETCs (EETCs), and finally to aircraft ABS. Today, both EETCs and aircraft lease-backed securities are widely used.

EETCs are corporate bonds that share some of the features of structured products, such as credit tranching and liquidity facilities. Aircraft ABS differ from EETCs in that they are not corporate bonds, and they are backed by leases to a number of airlines instead of being tied to a single airline. The rating of aircraft ABS is based primarily on the cash flow from their pool of aircraft leases or loans and the collateral value of that aircraft, not on the rating of lessee airlines.

One of the major characteristics that set aircraft ABS apart from other forms of aircraft financing is their diversification. ETCs and EETCs finance aircraft from a single airline. An aircraft ABS is usually backed by leases from a number of different airlines, located in a number of different countries and flying a variety of aircraft types. This diversification is a major attraction for investors. In essence, they are investing in a portfolio of airlines and aircraft types rather than a single airline—as in the case of an airline corporate bond. Diversification also is one of the main criteria that rating agencies look for in an aircraft securitization. The greater the diversification, the higher the credit rating, all else being equal.

Although there are various forms of financing that might appear in an aircraft ABS deal—including operating leases, financing leases, loans or mortgages—to date, the vast majority of the collateral in aircraft deals has been operating leases. In fact, all of the largest deals have been issued by aircraft leasing companies. This does not mean that a diversified finance company or an airline itself might not at some point bring a lease-backed or other aircraft ABS deal. It just means that so far, aircraft ABS have been mainly the province of leasing companies. Airlines, on the other hand, are active issuers of EETCs.

Aircraft leasing differs from general equipment leasing in that the useful life of an aircraft is much longer than most pieces of industrial or commercial equipment. In a typical equipment lease deal, cash flow from a particular lease on a particular piece of equipment only contributes to the ABS deal for the life of the lease. There is no assumption that the lease will be renewed. In aircraft leasing, the equipment usually has an original useful life of 20+ years, but leases run for only around 4 to 5 years. This means that the aircraft will have to be re-leased on expiration of the original leases. Hence, in the rating agencies' review, there is a great deal of focus on risks associated with re-leasing the aircraft.

The risk of being able to put the plane back out on an attractive lease can be broken down into three components: (1) the time it takes to re-lease the craft; (2) the lease rate; and (3) the lease term. Factors that can affect releasing include the general health of the economy, the health of the airline industry, obsolescence, and type of aircraft.

Servicing is important in many ABS sectors, but it is crucial in a lease-backed aircraft deal, especially when the craft must be remarketed when their lease terms expire before the term of the aircraft ABS. It is the ser-vicer's responsibility to re-lease the aircraft. To fulfill that function in a timely and efficient manner, the servicer must be both well-established and well-regarded by the industry.

As Moody's states, the servicer "should have a large and diverse presence in the global aircraft marketplace in terms of the number of aircraft controlled. Market share drives the ability of a servicer to meet aircraft market demand and deal with distressed airlines."

The servicer is also the key to maintaining value of the aircraft, through monitoring usage of the craft by lessees. If a lessee is not maintaining an aircraft properly, it is the servicer's responsibility to correct that situation. Because of servicers' vital role to the securitization, the rating agencies spend a great deal of effort ascertaining how well a servicer is likely to perform.

In addition to the risk from needing to re-lease craft, rating agencies are also concerned about possible defaults. Because of protections under Section 1110 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code, and international statutes that favor aircraft creditors, there is relatively little risk of losing an aircraft. There are, however, repossession costs, plus the loss of revenues during the time it takes to repossess and restore the aircraft to generating lease income.

The rating agencies will "stress" an aircraft financing by assuming a default rate and a period of time and cost for repossessing the aircraft. A major input into base default assumptions is the credit rating of airline lessees. For this part of the review, the ABS rating analyst does rely on the corporate rating of the airline.

While there is little risk of not recovering the aircraft in event of a default, the rating agencies do carefully review the legal and political risks that the aircraft may be exposed to, and evaluate the ease with which the aircraft can be repossessed in the event of a default, especially if any of the lessees are in developing countries.

In aircraft ABS, as in every other ABS sector, the rating agencies attempt to set enhancement levels that are consistent across asset types. That is, the risk of not receiving interest or principal in a aircraft deal rated a particular credit level should be the same as in a credit card or home equity deal (or, for that matter, even for a corporate bond) of the same rating. The total enhancement ranges from 34% to 47%.

Since the early deals, there has been a change in enhancement levels. Early deals depended largely on the sale of aircraft to meet principal payments on the bonds. Since then, aircraft ABS has relied more on lease revenue. Because lease revenue is more robust than sales revenue, the enhancement levels have declined. To understand why a "sales" deal requires more enhancement than a "lease" deal, consider the following. If an aircraft is sold during a recession, the deal suffers that entire decline in market value. On the other hand, if a lease rate declines during a recession, the deal sustains only the loss on the re-lease rate.

Franchise loan-backed securities are a hybrid between the commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) and ABS markets. They are often backed by real estate, as in CMBS, but the deal structures are more akin to ABS. Also, franchise loans resemble SBA loans and CDOs more than they do consumer loan-backed ABS securities. Greater reliance is placed on examining each franchise loan within the pool than on using aggregate statistics. In a pool of 100 to 200 loans (typical franchise loan group sizing) each loan is significant. By contrast within the consumer sector, any individual loan from a pool of 10,000 loans (as in home equity deals) does not represent as large a percentage, thus is not considered quite as important.

Franchise loans are similar to SBA loans in average size, maturity, and end use. But whereas most SBA loans are floating rate loans indexed to the prime rate, most securitized franchise loans are fixed rate; if they are floating, they are likely to be LIBOR linked. Franchise loans are used to fund working capital, expansion, acquisitions, and renovation of existing franchise facilities.

The typical securitized deal borrower owns a large number of units, as opposed to being a small individual owner of a single franchise unit. However, individual loans are usually made on a single unit, secured either by the real estate, the building, or the equipment in the franchise.

The consolidation within the industry and the emergence of large operators of numerous franchise units has improved industry credit performance. A company owning 10 to 100 units is in a better position to weather a financial setback than is the owner of a single franchise location.

Loans can also be either fixed or floating rate, and are typically closed-end, fully amortizing with maturities of 7 to 20 years. If secured by equipment, maturities range from 7 to 10 years. If they are secured by real estate, maturities usually extend 15 to 20 years. Interest rates range from 8% to 11%, depending on maturity and risk parameters.

Because franchise loan collateral is relatively new to the ABS market, and deal size is small, most of these securitized packages have been issued as a 144a private placement (Rule 144a of the Securities Act of 1933 governing private resales of securities to institutions). Issuers also prefer the 144a execution for competitive reasons, because they are reluctant to publicly disclose details of their transactions.

Deals typically range from $100 to $300 million, and are customarily backed by 150 to 200 loans. Average loan size is around, $500,000, while individuals loans may range from $15,000 to $2,000,000.

Most deals are structured as sequential-pay bonds with a senior/subordinate credit enhancement. Prepayments can occur if a franchise unit closes or is acquired by another franchisor. However, few prepayments have been experienced within securitized deals as of this writing, and most loans carry steep prepayment penalties that effectively discourage rate refinancing. Those penalties often equal 1% of the original balance of the loan.

The vast majority of franchise operations consist of three types of retail establishments: restaurants, specialty retail stores (e.g., convenience stores, Blockbuster, 7-11s, Jiffy Lube, and Meineke Muffler), and retail gas stations (e.g., Texaco and Shell). The restaurant category has three major subsectors: quick-service restaurants (e.g., McDonald's, Burger King, Wendy's, and Pizza Hut), casual restaurants (e.g., T.G.I. Fridays, Red Lobster, and Don Pablo's), and family restaurants (e.g., Denny's, Perkins, and Friendly's).

A "concept" is simply another name for a particular franchise idea, since each franchise seeks to differentiate itself from its competitors. Hence, even though Burger King and Wendy's are both quick-service restaurants specializing in sandwiches, their menu and style of service are sufficiently different that each has its own business/marketing plan—or "concept." For example, Wendy's has long promoted the "fresh" market, because the firm mandated fresh (not frozen) beef patties in their hamburgers, and helped pioneer the industry's salad bars. Burger King is noted for its "flame-broiled" burgers, and doing it "your way."

In addition to segmenting the industry by functional types, it is also segmented by credit grades. For example, Fitch developed a credit tiering system based on expected recoveries of defaulted loans. Tier I concepts have a much lower expected default level than Tier II concepts, and so on. Many financial and operational variables go into these tiered ratings, including number of outlets nationwide (larger, successful concepts benefit from better exposure, national advertising, and the like); concept "seasoning" (especially if it has weathered a recession); and viability in today's competitive environment. (Yesterday's darlings may have become oversaturated, or unable to respond to changing tastes or trends by revamping and updating!)

There are several risk factors to be aware of when comparing franchise loan pools, and the following are some of the most important.

Number of Loans/Average Size

High concentrations of larger loans represent increased risk, just as in any other pool of securitized loans.

Loan-to-Value Ratio

The loan-to-value (LTV) ratio can be based on either real estate or business values. It is important to determine which is being used in a particular deal in order to make a valid comparison with other franchise issues. Note that when business value is used to compute LTV, it is common for a nationally recognized accounting firm to provide the valuation estimate.

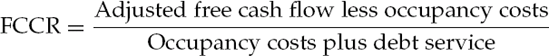

Fixed Charge Coverage Ratio

The fixed charge coverage ratio (FCCR) is calculated as follows:

Typical FCCRs range from 1.00 to 3.00, and average around 1.5. A deal with most unit FCCRs below 1.5 would be viewed as having greater risk than average, while one with most FCCRs above 1.5 would be perceived as having less risk than average.

Diversification

As in all ABS sectors, a primary risk factor is the degree of diversification. In a franchise loan deal, important areas for diversification include franchise owner, concept, and location.

A typical franchise pool includes loans to 10 to 15 franchisees, each having taken out loans on 5 to 20 individual units. A large concentration of loans to any single franchise operator might increase deal risk. However, such concentration is sometimes allowed, and rating agencies will not penalize severely if that particular franchisee has a very strong record and the individual franchise units have strong financials. It might even be better to have a high concentration of high-quality loans than a more diverse pool of weaker credits.

Concept diversification is also important. Franchise loans extend for 10 to 20 years, and a profitable concept today may become unprofitable as the loans mature.

It is not as important that pooled loans include representation across several major sectors (such as more than one restaurant subsector, or loans from all three major groups). Many finance companies specialize in one or two segments of the industry, and know their area well. Thus, a deal from only one of the major sectors does not add any measurable risk as long as there is diversification by franchisee and concept.

Geographical diversification is also important, as it reduces risk associated with regional economic recessions.

Control of Collateral

A key factor in the event of borrower (franchisee) default is control of the collateral. If a franchise loan is secured by a fee simple mortgage, the lender controls disposition of collateral in a bankruptcy. However, if that collateral is a leasehold interest (especially if the lessor is a third party and not the franchisor), the lender may not be able to control disposition in the event of default.

The concept of rate reduction bonds (RRBs)—also known as stranded costs or stranded assets—grew out of the movement to deregulate the electric utility industry and bring about a competitive market environment for electric power. Deregulating the electric utility market was complicated by large amounts of "stranded assets" already on the books of many electric utilities. These stranded assets were commitments that had been undertaken by utilities at an earlier time with the understanding that they would be recoverable in utility rates to be approved by the states' utility commissions. However, in a competitive environment for electricity, these assets would likely become uneconomic, and utilities would no longer be assured that they could charge a high enough rate to recover the costs. To compensate investors of these utilities, a special tariff was proposed. This tariff, which would be collected over a specified period of time, would allow the utility to recover its stranded costs.

This tariff, which is commonly known as the competitive transition charge (CTC), is created through legislation. State legislatures allow utilities to levy a fee, which is collected from its customers. Although there is an incremental fee to the consumer, the presumed benefit is that the utility can charge a lower rate as a result of deregulation. This reduction in rates would more than offset the competitive transition charge. In order to facilitate the securitization of these fees, legislation typically designates the revenue stream from these fees as a statutory property right. These rights may be sold to an SPV, which may then issue securities backed by future cash flows from the tariff.

The result is a structured security similar in many ways to other ABS products, but different in one critical aspect: The underlying asset in a RRB deal is created by legislation, which is not the case for other ABS products.

In the first quarter of 2001 there was a good deal of concern regarding RRBs. The sector came under intense scrutiny as a result of the financial problems experienced by California's major utilities. Yet despite the bankruptcy motion filed by Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) in 2001—a bellwether issuer of RRBs—rating agencies maintained their triple-A ratings on California's existing RRB issues. This is not the first time the RRB sector had found itself in turmoil. Over much of 1998, the sector was roiled by a movement in California to overturn the existing legislation that had been created specifically for RRB securitization. This put existing RRB issues in jeopardy. However, the ultimate result—a voter initiative was defeated—proved to be positive for this product. The ability of this asset class to retain its rating despite a significant credit crisis at an underlying utility, as well as a serious challenge to the legislation that allows for the creation of these securities, speaks volumes for the soundness of the structures of RRB deals.

As noted above, state regulatory authorities and/or state legislatures must take the first step in creating RRB issues. State regulatory commissions decide how much, if any, of a specific utility's stranded assets will be recaptured via securitization. They will also decide on an acceptable time frame and collection formula to be used to calculate the CTC. When this legislation is finalized, the utility is free to proceed with the securitization process.

The basic structure of an RRB issue is straightforward. The utility sells its rights to future CTC cash flows to an SPV created for the sole purpose of purchasing these assets and issuing debt to finance this purchase. In most cases, the utility itself will act as the servicer because it collects the CTC payment from its customer base along with the typical electric utility bill. Upon issuance, the utility receives the proceeds of the securitization (less the fees associated with issuing a deal), effectively reimbursing the utility for its stranded costs immediately.

RRBs usually have a "true-up" mechanism. This mechanism allows the utility to recalculate the CTC on a periodic basis over the term of the deal. Because the CTC is initially calculated based on projections of utility usage and the ability of the servicer to collect revenues, actual collection experience may differ from initial projections. In most cases, the utility can re-examine actual collections, and if the variance is large enough (generally a 2% difference), the utility will be allowed to revise the CTC charge. This true-up mechanism provides cash flow stability as well as credit enhancement to the bondholder.

Credit enhancement levels required by the rating agencies for RRB deals are very low relative to other ABS asset classes. Although exact amounts and forms of credit enhancement may vary by deal, most transactions require little credit enhancement because the underlying asset (the CTC) is a statutory asset and is not directly affected by economic factors or other exogenous variables. Furthermore, the true-up mechanism virtually assures cash flow stability to the bondholder.

As an example, the AAA-rated bonds Detroit Edison Securitization Funding 1 issued in March 2001 were structured with 0.50% initial cash enhancement (funded at closing) and 0.50% overcollateralization (to be funded in equal semiannual increments over the terms of the transactions). This total of 1% credit enhancement is minuscule in comparison to credit cards, for example, which typically require credit enhancement at the AAA level in the 12% to 15% range for large bank issuers.

RRBs are subject to risks that are very different from those associated with more traditional structured products (e.g., credit cards, home equity loans, and so on). For example, risks involving underwriting standards do not exist in the RRB sector because the underlying asset is an artificial construct. Underwriting standards are a critical factor in evaluating the credit of most other ABS. Also, factors that tend to affect the creditworthiness of many other ABS products—such as levels of consumer credit or the economic environment—generally do not have a direct effect on RRBs. Instead, other unique factors that must be considered when evaluating this sector. The most critical risks revolve around the legislative process and environment plus the long-term ability of the trust to collect future revenues to support the security's cash flows.

In this chapter we described the characteristics of seven types of ABSs for which the asset pool consists of traditional nonmortgage assets: credit card receivable-backed securities, auto loan-backed securities, student loan-backed securities, SBA loan-backed securities, aircraft lease-backed securities, franchise loan-backed securities, and rate reduction bonds.

Anderson, J. S., and Clark, K. L. (2000). Franchise loan securitization. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 187-202). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Anderson, J. S., Shannon, S. H., and Clark, K. L. (2000). Equipment-financed ABS. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 139-150). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Bakalar, N., and Nimberg, J. (2000). Securities backed by recreational vehicle loans. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 101-138). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Batchvarov, A., Collins, J., and Davies, W (2004). European mezzanine loan securitisations. In F. J. Fabozzi and M. Choudhry (eds.), The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products (pp. 252-262). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Davidson, A., Sanders, A., Wolff, L-L, and Ching, A. (2003). Securitization: Structuring and Investment Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Dennis, A. (2004). Securitisation of UK pubs. In F. J. Fabozzi and M. Choudhry (eds.), The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products (pp. 389–410). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, F. J. (2005). The structured finance market: An investor's perspective. Financial Analysts Journal 60, 3: 27-40.

Fabozzi, F. J., and Kothari, V. (2008). Introduction to Securitization. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Faulk, D. (1996). SBA loan-backed securities. In A. K. Bhattacharya and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 167-178). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Flanagan, C, and Tan, W (2000). SBA Development Company participation certificates. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 169-188). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Gintz, C. (2004). Stock securitisations. In F. J. Fabozzi and M. Choudhry (eds.), The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products (pp. 263-272). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kothari, V. (2006). Securitization: The Financial Instrument of the Future, 3rd edition. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons.

Lucas, J., and Zimmerman, T. (1996). Equipment lease-backed securities. In A. K. Bhattacharya and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 147-166). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

McElravey, J. (2005). Credit card asset-backed securities. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 7th edition (pp. 629-646). New York: McGraw-Hill.

McPherson, N. (2000). Healthcare receivable backed ABS. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 211-222). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

McPherson, N. (2000). Securities backed by auto loans and leases. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 61-100). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Neimier, M. (2004). European credit card ABS. In F. J. Fabozzi and M. Choudhry (eds.), The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products (pp. 177-200). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Neimier, M. (2004). European auto and consumer loan ABS. In F. J. Fabozzi and M. Choudhry (eds.), The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products (pp. 201-222). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Philips, J., and Hsiang, O. (2000). Aircraft asset-backed securities. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 151-168). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Pica, V. T., and Bhattacharya, A. K. (1996). In A. K. Bhattacharya and F. J. Fabozzi (eds.), Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 179-186). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Quisenberry, J. O. (1998). Securitization of non-traditional asset types: An investor's perspective. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Structured Financial Products (pp. 21-28). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Ramgarhia, A., Muminoglu, M., and Pankratov, O. (2004). Whole business securitisation. In F. J. Fabozzi and M. Choudhry (eds.), The Handbook of European Structured Financial Products (pp. 329-338). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Roever, W (2005). Securities backed by automobile loans and leases. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 7th edition (pp. 647-668). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Schorin, C. N. (1998). Auto lease ABS. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Structured Financial Products (pp. 139-151). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Schorin, C. N. (1998). Credit card asset-backed securities. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Structured Financial Products (pp. 153-178). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Schorin, C. N., and Roach, K. (1998). Utility stranded costs securitization. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Structured Financial Products (pp. 263-270). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Thompson, A.V. (1998). Securitization of commercial and industrial loans. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Structured Financial Products (pp. 235-240). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wagner, K., and Callahan, E. (1998). Student loan ABS. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Handbook of Structured Financial Products (pp. 201-234), Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Weaver, K., and Bakalar, N. (2000). In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 223-238). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Zimmerman, T. (2000). Student loan floaters. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), Investing in Asset-Backed Securities (pp. 203-210). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.