MARK J. P. ANSON, PhD, JD, CPA, CFA, CAIA

President and Executive Director of Nuveen Investment Services

Abstract: The global hedge fund market is estimated at $1.4 trillion. This capital has flowed into hedge funds because of their unrestricted ability to invest across asset classes, to go both long and short securities, and to invest without the burden or constraint of a traditional benchmark. However, investing in hedge funds is not easy. They may pursue esoteric strategies and may take on considerable leverage to boost their returns. Nonetheless, their popularity persists because of their ability to generate returns from pricing discrepancies in the financial markets. Still, successful investing in hedge funds requires considerable due diligence—a process that requires both time and patience.

Keywords: hedge fund, market directional, corporate restructuring, convergence trading, opportunistic, equity long/short, market timers, short sellers, distressed securities, merger arbitrage, event driven, fixed income arbitrage, convertible bond arbitrage, market neutral, statistical arbitrage, relative-value arbitrage, global macro, fund of funds, due diligence, absolute return

The phrase "hedge fund" is a term of art. It is not defined in the Securities Act of 1933 or the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Additionally, "hedge fund" is not defined by the Investment Company Act of 1940, the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, the Commodity Exchange Act, or, finally, the Bank Holding Company Act. Even though the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has attempted (unsuccessfully) to regulate hedge funds, it has yet to define the term hedge fund within its security regulations. So what is this investment vehicle that every investor seems to know but for which there is scant regulatory guidance?

As a starting point, we turn to the American Heritage Dictionary, 3rd edition, which defines a hedge fund as:

An investment company that uses high-risk techniques, such as borrowing money and selling short, in an effort to make extraordinary capital gains.

This is a good start; however, many hedge fund strategies use tightly controlled, low-risk strategies to produce consistent but conservative rates of return and do not "swing for the fences" to earn extraordinary gains.

We define hedgefund as a privately organized investment vehicle that manages a concentrated portfolio of public and private securities and derivative instruments on those securities, that can invest both long and short and can apply leverage.

In this chapter we will discuss the various types of hedge funds according to the investment strategies that they pursue and considerations in investing in hedge funds.

Within this definition there are six key elements of hedge funds that distinguish them from their more traditional counterpart, the mutual fund.

First, hedge funds are private investment vehicles that pool the resources of sophisticated investors. One of the ways that hedge funds avoid the regulatory scrutiny of the SEC or the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) is that they are available only for high-net-worth investors. Under SEC rules, hedge funds cannot have more than 100 accredited investors in the fund. An accredited investor is defined as an individual that has a minimum net worth in excess of $1 million, or income in each of the past two years of $200,000 ($300,000 for a married couple) with an expectation of earning at least that amount in the current year. Additionally, hedge funds may accept no more than 500 "qualified purchasers" in the fund. These are individuals or institutions that have a net worth in excess of $5 million.

There is a penalty, however, for the privacy of hedge funds. They cannot raise funds from investors via a public offering. Additionally, hedge funds may not advertise broadly or engage in a general solicitation for new funds. Instead, their marketing and fund-raising efforts must be targeted to a narrow niche of very wealthy individuals and institutions. As a result, the predominant investors in hedge funds are family offices, foundations, endowments, and, to a lesser extent, pension funds.

Second, hedge funds tend to have portfolios that are much more concentrated than their mutual fund brethren. Most hedge funds do not have broad securities benchmarks. One reason is that most hedge fund managers claim that their style of investing is "skill based" and cannot be measured by a market return. Consequently, hedge fund managers are not forced to maintain security holdings relative to a benchmark; they do not need to worry about "benchmark" risk. This allows them to concentrate their portfolio on only those securities that they believe will add value to the portfolio.

Another reason for the concentrated portfolio is that hedge fund managers tend to have narrow investment strategies. These strategies tend to focus on only one sector of the economy or one segment of the market. They can tailor their portfolio to extract the most value from their smaller investment sector or segment. Furthermore, the concentrated portfolios of hedge fund managers generally are not dependent on the direction of the financial markets, in contrast to long-only managers.

Third, hedge funds tend to use derivative strategies much more predominantly than mutual funds. Indeed, in some strategies, such as convertible arbitrage, the ability to sell or buy options is a key component of executing the arbitrage. The use of derivative strategies may result in nonlinear cash flows that may require more sophisticated risk management techniques to control these risks.

Fourth, hedge funds may go both long and short securities. The ability to short public securities and derivative instruments is one of the key distinctions between hedge funds and traditional money managers. Hedge fund managers incorporate their ability to short securities explicitly into their investment strategies. For example, equity long/short hedge funds tend to buy and sell securities within the same industry to maximize their return but also to control their risk. This is very different from traditional money managers that are tied to a long-only securities benchmark.

Fifth, many hedge fund strategies invest in nonpublic securities, that is, securities that have been issued to investors without the support of a prospectus and a public offering. Many bonds, both convertible and high yield, are issued as what are known as "144A securities." These are securities issued to institutional investors in a private transaction instead of a public offering. These securities may be offered with a private placement memorandum (ppm), but not a public prospectus. In addition, these securities are offered without the benefit of an SEC review as would be conducted for a public offering. Bottom line: with 144A securities it is buyer beware. The SEC allows this because, presumably, large institutional investors are more sophisticated than that average, small investor.

Finally, hedge funds use leverage, sometimes, large amounts. In fact, a lesson in leverage is described in this chapter with respect to Long-Term Capital Management. Mutual funds, for example, are limited in the amount of leverage they can employ; they may borrow up to 33% of their net asset base. Hedge funds do not have this restriction. Consequently, it is not unusual to see some hedge fund strategies that employ leverage up to 10 time their net asset base.

We can see that hedge funds are different than traditional long-only investment managers.

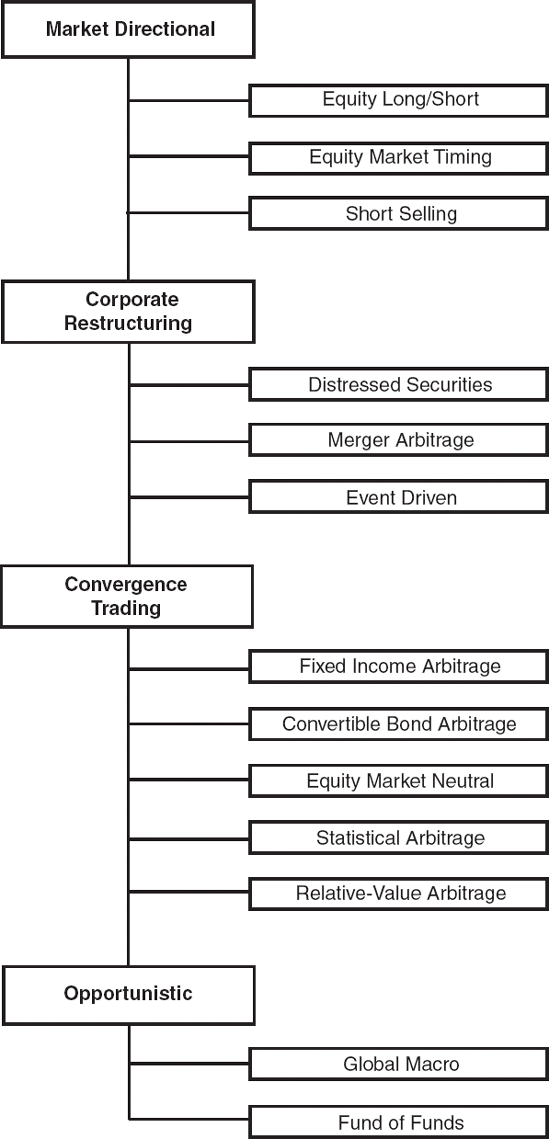

It seems like everyone has their own classification scheme for hedge funds (see, for example, L'habitant [2004] and Nicholas [2000]). This merely reflects the fact that hedge funds are a bit difficult to "box in"—a topic we will address further when we examine a number of the hedge fund index providers. For purposes of this book, we try to break down hedge funds into broad categories, as depicted in Figure 53.1.

We classify hedge funds into four broad buckets: market directional, corporate restructuring, convergence trading, and opportunistic. Market directional hedge funds are those that retain some amount of systematic risk exposure. For example, equity long/short (or, as it is sometime called, equity hedge) are hedge funds that typically contain some amount of net long market exposure. For example, they may leverage up the hedge fund to go 150% long on stocks that they like while simultaneously shorting 80% of the fund value with stocks that they think will decline in value. The remaining net long market exposure is 70%. Thus, they retain some amount of systematic risk exposure that will be affected by the direction of the stock market.

Corporate restructuring hedge funds take advantage of significant corporate transactions like mergers, acquisitions, or bankruptcies. These funds earn their living by concentrating their portfolios on a handful of companies where it is more important to understand the likelihood that the corporate transaction will be completed than it is to determine whether the corporation is under-or overvalued.

Convergence trading hedge funds are the hedge funds that practice the art of arbitrage. In fact, the specialized subcategories within this bucket typically contain the word arbitrage in their description, such as statistical arbitrage, fixed income arbitrage, or convertible arbitrage. In general, these hedge funds make bets that two similar securities but with dissimilar prices will converge to the same value over the investment holding period.

Finally, we have the opportunistic category. We include global macrohedge funds as well as fund of funds (FOF) in this category. These funds are designed to take advantage of whatever opportunities present themselves, hence the term opportunistic. For example, FOF often practice tactical asset allocation among the hedge funds contained in the FOF based on the FOF manager's view as to which hedge fund strategies are currently poised to earn the best results. This shifting of the assets around is based on the FOF manager's assessment of the opportunity for each hedge fund contained in the FOF to earn a significant return.

Hedge funds invest in the same equity and fixed income securities as traditional long-only managers. Therefore, it is not the alternative "assets" in which hedge funds invest that differentiates them from long-only managers, but rather, it is the alternative investment strategies that they pursue. In this section we provide more detail on the types of strategies pursued by hedge fund managers.

The strategies in this bucket of hedge funds either retain some systematic market exposure associated with the stock market such as equity long/short or are specifically driven by the movements of the stock market such as market timing or short selling.

Equity Long/Short

Equity long/short managers build their portfolios by combining a core group of long stock positions with short sales of stock or stock index options/futures. Their net market exposure of long positions minus short positions tends to have a positive bias. That is, equity long/short managers tend to be long market exposure. The length of their exposure depends on current market conditions. For instance, during the great stock market surge of 1996 to 1999, these managers tended to be mostly long their equity exposure. However, as the stock market turned into a bear market in 2000 to 2002, these managers decreased their market exposure as they sold more stock short or sold stock index options and futures.

The ability to go both long and short in the market is a powerful tool for earning excess returns. The ability to fully implement a strategy not only about stocks and sectors that are expected to increase in value but also stocks and sectors that are expected to decrease in value allows the hedge fund manager to maximize the value of her market insights.

Equity long/short hedge funds essentially come in two flavors: fundamental or quantitative. Fundamental long/short hedge funds conduct traditional economic analysis on a company's business prospects compared to its competitors and the current economic environment. These shops will visit with management, talk with Wall Street analysts, contact customers and competitors and essentially conduct bottom-up analysis. The difference between these hedge funds and long-only managers is that they will short the stocks that they consider to be poor performers and buy those stocks that are expected to outperform the market. In addition, they may leverage their long and short positions.

Fundamental long/short equity hedge funds tend to invest in one economic sector or market segment. For instance, they may specialize in buying and selling Internet companies (sector focus) or buying and selling small market capitalization companies (segment focus).

In contrast, quantitative equity long/short hedge fund managers tend not to be sector or segment specialists. In fact, quite the reverse, quantitative hedge fund managers like to cast as broad a net as possible in their analysis. These managers are often referred to as statistical arbitrageurs because they base their trade selection on the use of quantitative statistics instead of fundamental stock selection.

Market Timers

Market timers, as their name suggests, attempt to time the most propitious moments to be in the market and invest in cash otherwise. More specifically, they attempt to time the market so that they are fully invested during bull markets, and strictly in cash during bear markets.

Unlike equity long/short strategies, market timers use a top-down approach as opposed to a bottom-up approach. Market-timing hedge fund managers are not stock pickers. They analyze fiscal and monetary policy as well as key macroeconomic indicators to determine whether the economy is gathering or running out of steam.

Macroeconomic variables they may analyze are labor productivity, business investment, purchasing managers' surveys, commodity prices, consumer confidence, housing starts, retail sales, industrial production, balance of payments, current account deficits/surpluses, and durable good orders.

They use this macroeconomic data to forecast the expected gross domestic product (GDP) for the next quarter. Forecasting models typically are based on multifactor linear regressions, taking into account whether a variable is a leading or lagging indicator and whether the variable experiences any seasonal effects.

Once market timers have their forecast for the next quarter(s), they position their investment portfolio in the market according to their forecast. Construction of their portfolio is quite simple. They do not need to purchase individual stocks. Instead, they buy or sell stock index futures and options to increase or decrease their exposure to the market as necessary. At all times, contributed capital from investors is kept in short-term, risk-free, interest bearing accounts. Treasury bills are often purchased, which not only yield a current risk-free interest rate, but also can be used as margin for the purchase of stock index futures.

When a market timer's forecast is bullish, he may purchase stock index futures with an economic exposure equivalent to the contributed capital. He may apply leverage by purchasing futures contracts that provide an economic exposure to the stock market greater than that of the underlying capital. However, market timers generally do not borrow investment capital.

When the hedge fund manager is bearish, he will trim his market exposure by selling futures contracts. If he is completely bearish, he will sell all of his stock index futures and call options and just sit on his cash portfolio. Some market timers may be more aggressive and short stock index futures and buy stock index put options to take advantage of bear markets.

In general, though, market timers tend to have long exposure to the market at all times, making them market directional. However, they attempt to trim this exposure when markets appear bearish. This was demonstrated during the bear market years of 2000 to 2002. Consequently, we find that market timers have a similar, but slightly more conservative, risk profile than the stock market.

Short Selling

Short selling hedge funds have the opposite exposure of traditional long-only managers. In that sense, their return distribution should be the mirror image of long-only managers: they make money when the stock market is declining and lose money when the stock market is gaining.

These hedge fund managers may be distinguished from equity long/short managers in that they generally maintain a net short exposure to the stock market. However, short selling hedge funds tend to use some form of market timing. That is, they trim their short positions when the stock market is increasing and go fully short when the stock market is declining. When the stock market is gaining, short sellers maintain that portion of their investment capital not committed to short selling in short-term interest rate-bearing accounts.

Many hedge fund articles call these strategies "event driven" or "risk arbitrage," but that does not really describe what is at the heart of each of these type of strategies. The focal point is some form of corporate restructuring such as a merger, acquisition, or bankruptcy. Companies that are undergoing a significant transformation generally provide an opportunity for trading around that event. These strategies are driven by the deal, not by the market.

Distressed Securities

Distressed debt hedge funds invest in the securities of a corporation that is in bankruptcy, or is likely to fall into bankruptcy. Companies can become distressed for any number of reasons such as too much leverage on their balance sheet, poor operating performance, accounting irregularities, or even competitive pressure. Some of these strategies can overlap with private equity strategies that we will discuss in Part Four of this book. The key difference here is that hedge funds are less concerned with the fundamental value of a distressed corporation and, instead, concentrate on trading opportunities surrounding the company's outstanding stock-and-bond securities.

There are many different variations on how to play a distressed situation, but most fall into three categories. In its simplest form, the easiest way to profit from a distressed corporation is to sell its stock short. This requires the hedge fund manager to borrow stock from its prime broker and sell in the marketplace stock that it does not own with the expectation that the hedge fund manager will be able to purchase the stock back at a later date and at a cheaper price as the company continues to spiral downward in its distressed situation. This is nothing more than "sell high and buy low."

However, the short selling of a distressed company exposes the hedge fund manager to significant risk if the company's fortunes should suddenly turn around. Therefore, most hedge fund managers in this space typically use a hedging strategy within a company's capital structure.

A second form of distressed securities investing is called capital structure arbitrage. Consider Company A, which has four levels of outstanding capital: senior secured debt, junior subordinated debt, preferred stock, and common stock. A standard distressed security investment strategy would be to:

Buy the senior secured debt and short the junior subordinated debt.

Buy the preferred stock and short the common stock.

In a bankruptcy situation, the senior secured debt stands in line in front of the junior subordinated debt for any bankruptcy-determined payouts. The same is true for the preferred stock compared to Company A's common stock. Both the senior secured debt and the preferred stock enjoy a higher standing in the bankruptcy process than either junior debt or common equity. Therefore, when the distressed situation occurs or progresses, senior secured debt should appreciate in value relative to the junior subordinated debt. In addition, there should be an increase in the spread of prices between preferred stock and common stock. When this happens, the hedge fund manager closes out her positions and locks in the profit that occurs from the increase in the spread.

Finally, distressed securities hedge funds can become involved in the bankruptcy process to find significantly undervalued securities. This is where an overlap with private equity firms can occur. To the extent that a distressed securities hedge fund is willing to learn the arcane workings of the bankruptcy process and to sit on creditor committees, significant value can be accrued if a distressed company can restructure and regain its footing. In a similar fashion, hedge fund managers do purchase the securities of a distressed company shortly before it announces its reorganization plan to the bankruptcy court with the expectation that there will be a positive resolution with the company's creditors.

Merger Arbitrage

Merger arbitrage is perhaps the best-known corporate restructuring investment among investors and hedge fund managers. Merger arbitrage generally entails buying the stock of the firm that is to be acquired and selling the stock of the firm that is the acquirer. Merger arbitrage managers seek to capture the price spread between the current market prices of the merger partners and the value of those companies upon the successful completion of the merger.

The stock of the target company usually trades at a discount to the announced merger price. The discount reflects the risk inherent in the deal; other market participants are unwilling to take on the full exposure of the transaction-based risk. Merger arbitrage is then subject to event risk. There is the risk that the two companies will fail to come to terms and call off the deal. There is the risk that another company will enter into the bidding contest, ruining the initial dynamics of the arbitrage. There is finally regulatory risk. Various U.S. and foreign regulatory agencies may not allow the merger to take place for antitrust reasons. Merger arbitrageurs specialize in assessing event risk and building a diversified portfolio to spread out this risk.

Merger arbitrageurs conduct significant research on the companies involved in the merger. They will review current and prior financial statements, SEC electronic data gathering analysis and retrieval (EDGAR) filings, proxy statements, management structures, cost savings from redundant operations, strategic reasons for the merger, regulatory issues, press releases, and competitive position of the combined company within the industries in which it competes. Merger arbitrageurs will calculate the rate of return that is implicit in the current spread and compare it to the event risk associated with the deal. If the spread is sufficient to compensate for the expected event risk, they will execute the arbitrage.

Once again, the term arbitrage is used loosely. As discussed earlier, there is plenty of event risk associated with a merger announcement. The profits earned from merger arbitrage are not riskless. Consider the saga of the purchase of MCI Corporation by Verizon Communications. Throughout 2005, Verizon was in a bidding war against Qwest Communications for the purchase of MCI. On February 3, 2005, Qwest announced a $6.3 billion merger offer for MCI. This bid was quickly countered by Verizon on February 10 that matched the $6.3 billion bid established by Qwest. The bidding war raged back and forth for several months before Verizon finally won the day in October of 2005 with an ultimate purchase price of $8.44 billion.

To see the vicissitudes of merger arbitrage at work, we follow both the successful Verizon bid for MCI as well as the unsuccessful bid by Qwest.

Starting with Verizon: at the announcement of its bid for MCI, its stock was trading at $36.00, while MCI was trading at $20. Therefore, the merger arbitrage trade was:

| Sell 1,000 shares of Verizon at $36 (short proceeds of $36,000). |

| Buy 1,000 shares of MCI at $20 (cash outflow of $20,000). |

| While for the Qwest bid, the trade was: |

| Sell 1,000 shares of Qwest at $4.20 (short proceeds of $4,200). |

| Buy 1,000 shares of MCI at $20 (cash outflow of $20,000). |

Throughout the spring and summer of 2005, Qwest and Verizon battled it out for MCI, with Verizon ultimately winning in October 2005. At that time, MCI's stock had increased in value to $25.50, while Verizon's stock had lost value and was trading at $30, and finally Qwest was trading unchanged at $4.20.

Total return for the MCI/Verizon merger arbitrage trade:

Gain on MCI long position: | 1,000 × ($25.50 - $20) | = | $5,500 |

Gain on Verizon short position: | 1,000 × ($36 - $30) | = | $6,000 |

Interest on short rebate: | 4% × 1,000 × $36 × 240/360 | = | $960 |

Total | $12,460 |

The return on invested capital is: $12,460 ÷ $20,000 = 62.3%.

If the merger arbitrage manager had applied 50% leverage to this deal and borrowed half of the net outflow, the return would have been (ignoring financing costs):

| $12,460 ÷ $10,000 = 124.6% Total return |

Turning to the MCI/Qwest merger arbitrage trade, the total return was:

Gain on MCI long position | 1,000 × ($25.50 - $20) | = | $5,500 |

Gain on Qwest short position: | 1,000 × ($4.20 - $4.20) | = | $0 |

Gain on short rebate: | 4% × 1,000 × $4.20 × 240/360 | = | $112 |

Total | $5,612 |

The return on invested capital is: $5,612 ÷ $20,000 = 28.06%. With 50% leverage the return would be: $5,612 ÷ $10,000 = 56.12%.

While both merger arbitrage trades made money, clearly, it made more sense to bet on the Verizon/MCI merger than the Qwest/MCI merger. This is where merger arbitrage managers make their money, by assessing the likelihood of one bid over another. Also, in a situation where there are two bidders for a company, there is a very high probability that there will be a successful merger with one of the bidders. Consequently, many merger arbitrage hedge fund managers will play both bids. This is exactly what happened in the MCI deal—many merger arbitrage managers bet on both the MCI/Verizon deal and the MCI/Qwest deal, expecting that one of the two suitors would be successful in winning the hand of MCI.

Some merger arbitrage managers invest only in announced deals. However, other hedge fund managers will put on positions on the basis of rumor or speculation. The deal risk is much greater with this type of strategy, but so too is the merger spread (the premium that can be captured).

To control for risk, most merger arbitrage hedge fund managers have some risk of loss limit at which they will exit positions. Some hedge fund managers concentrate only on one or two industries, applying their specialized knowledge regarding an economic sector to their advantage. Other merger arbitrage managers maintain a diversified portfolio across several industries to spread out the event risk.

Merger arbitrage is deal driven rather than market driven. Merger arbitrage derives its return from the relative value of the stock prices between two companies as opposed to the status of the current market conditions. Consequently, merger arbitrage returns should not be highly correlated with the general stock market.

Event Driven

Event-driven hedge funds are very similar, in their approach to investing, to distressed securities and merger arbitrage. The only difference is that their mandate is broader than the other two corporate restructuring strategies. Event-driven transactions include mergers and acquisitions, spin-offs, tracking stocks, accounting writeoffs, reorganizations, bankruptcies, share buybacks, special dividends, and any other significant market event. Event-driven managers are nondiscriminatory in their transaction selection.

By their very nature, these special events are nonrecurring. Therefore, the financial markets typically do not digest the information associated with these transactions in a timely manner. The financial markets are simply less efficient when it comes to large, isolated transactions. This provides an opportunity for event-driven managers to act quickly and capture a premium in the market. Additionally, most of these events may be subject to certain conditions such as shareholder or regulatory approval. Therefore, there is significant deal risk associated with this strategy for which a savvy hedge fund manager can earn a return premium. The profitability of this type of strategy is dependent on the successful completion of the corporate transaction within the expected time frame.

Hedge fund managers tend to use the term arbitrage somewhat loosely. Arbitrage is defined simply as riskless profits. It is the purchase of a security for cash at one price and the immediate resale for cash of the same security at a higher price. Alternatively, it may be defined as the simultaneous purchase of security A for cash at one price and the selling of identical security B for cash at a higher price. In both cases, the arbitrageur has no risk. There is no market risk because the holding of the securities is instantaneous. There is no basis risk because the securities are identical, and there is no credit risk because the transaction is conducted in cash.

Instead of riskless profits, in the hedge fund world, arbitrage is generally used to mean low-risk investments. Instead of the purchase and sale of identical instruments, there is the purchase and sale of similar instruments. The securities also may not be sold for cash, so there may be credit risk during the collection period. Finally, the purchase and sale may not be instantaneous. The arbitrageur may need to hold onto its positions for a period of time, exposing him to market risk.

Fixed Income Arbitrage

Fixed income arbitrage involves purchasing one fixed income security and simultaneously selling a similar fixed income security with the expectation that over the investment holding period, the two security prices will converge to a similar value. Hedge fund managers search continuously for these pricing inefficiencies across all fixed income markets. This is nothing more than buying low and selling high and waiting for the undervalued security to increase in value or the overvalued security to decline in value, or wait for both to occur.

The sale of the second security is done to hedge the underlying market risk contained in the first security. Typically, the two securities are related either mathematically or economically such that they move similarly with respect to market developments. Generally, the difference in pricing between the two securities is small, and this is what the fixed income arbitrageur hopes to gain. By buying and selling two fixed income securities that are tied together, the hedge fund manager hopes to capture a pricing discrepancy that will cause the prices of the two securities to converge over time.

However, because the price discrepancies can be small, the way hedge fund managers add more value is to leverage their portfolio through direct borrowings from their prime broker, or by creating leverage through swaps and other derivative securities. Bottom line: They find pricing anomalies, then "crank up the volume" through leverage.

Fixed income arbitrage does not need to use exotic securities. For example, it can be nothing more than buying and selling U.S. Treasury bonds. In the bond market, the most liquid securities are the on-the-run Treasury bonds. These are the most currently issued bonds issued by the U.S. Treasury Department. However, there are other U.S. Treasury bonds outstanding that have very similar characteristics to the on-the-run Treasury bonds. The difference is that off-the-run bonds were issued at an earlier date, and are now less liquid than the on-the-run bonds. As a result, price discrepancies occur. The difference in price may be no more than one-half or one quarter of a point ($25) but can increase in times of uncertainty when investor money shifts to the most liquid U.S. Treasury bond. During the Russian bond default crisis, for example, on-the-run U.S. Treasuries were valued as much as $100 more than similar, off-the-run U.S. Treasury bonds of the same maturity.

Nonetheless, when held to maturity, the prices of these two bonds will converge to the same value. Any difference will be eliminated by the time they mature, and any price discrepancy may be captured by the hedge fund manager.

Fixed income arbitrage is not limited to the U.S. Treasury market. It can be used with corporate bonds, municipal bonds, sovereign debt, or mortgage-backed securities.

Another form of fixed income arbitrage involves trading among fixed income securities that are close in maturity. This is a form of yield curve arbitrage. These types of trades are driven by temporary imbalances in the term structure of interest rates.

Still another subset of fixed income arbitrage uses mortgage-backed securities (MBSs). MBSs represent an ownership interest in an underlying pool of individual mortgages loaned by banks and other financial institutions. Therefore, an MBS is a fixed income security with underlying prepayment options. MBS hedge funds seek to capture pricing inefficiencies in the U.S. mortgage-backed market.

MBS arbitrage can be between fixed income markets, such as buying MBS and selling U.S. Treasuries. This investment strategy is designed to capture credit spread inefficiencies between U.S. Treasuries and MBSs. MBSs trade at a credit spread over U.S. Treasuries to reflect the uncertainty of cash flows associated with MBSs compared to the lack of credit risk associated with U.S. Treasury bonds.

During a flight to quality, investors tend to seek out the most liquid markets such as the on-the-run U.S. Treasury market. This may cause credit spreads to temporarily increase beyond what is historically or economically justified. In this case the MBS market will be priced "cheap" to U.S. Treasuries. The arbitrage strategy would be to buy MBS and sell U.S. Treasury, where the interest rate exposure of both instruments is sufficiently similar so as to eliminate most (if not all) of the market risk between the two securities. The expectation is that the credit spread between MBSs and U.S. Treasuries will decline and MBS bonds will increase in value relative to U.S. Treasuries.

MBS arbitrage can be quite sophisticated. MBS hedge fund managers use proprietary models to rank the value of MBS by their option-adjusted spread (OAS). The hedge fund manager evaluates the present value of an MBS by explicitly incorporating assumptions about the probability of prepayment options being exercised. In effect, the hedge fund manager calculates the option-adjusted price of the MBS and compares it to its current market price. The OAS reflects the MBS's average spread over U.S. Treasury bonds of a similar maturity, taking into account the fact that the MBS may be liquidated early from the exercise of the prepayment option by the underlying mortgagors.

The MBSs that have the best OAS compared to U.S. Treasuries are purchased, and then their interest rate exposure is hedged to zero. Interest rate exposure is neutralized using Treasury bonds, options, swaps, futures, and caps. MBS hedge fund managers seek to maintain a duration of zero. This allows them to concentrate on selecting the MBSs that yield the highest OAS.

There are many risks associated with MBS arbitrage. Chief among them are duration, convexity, yield curve rotation, prepayment risk, credit risk, and liquidity risk. Hedging these risks may require the purchase or sale of other MBS products such as interest-only strips and principal-only strips, U.S. Treasuries, interest rate futures, swaps, and options.

What should be noted about fixed income arbitrage strategies is that they do not depend on the direction of the general financial markets. Arbitrageurs seek out pricing inefficiencies between two securities instead of making bets on market direction.

Convertible Bond Arbitrage

Convertible bonds combine elements of both stocks and bonds in one package. A convertible bond is a bond that contains an embedded option to convert the bond into the underlying company's stock.

Convertible arbitrage funds build long positions of convertible bonds and then hedge the equity component of the bond by selling the underlying stock or options on that stock. Equity risk can be hedged by selling the appropriate ratio of stock underlying the convertible option. This hedge ratio is known as the "delta" and is designed to measure the sensitivity of the convertible bond value to movements in the underlying stock.

Convertible bonds that trade at a low premium to their conversion value tend to be more correlated with the movement of the underlying stock. These convertibles then trade more like stock than they do a bond. Consequently a high hedge ratio, or delta, is required to hedge the equity risk contained in the convertible bond. Convertible bonds that trade at a premium to their conversion value are highly valued for their bondlike protection. Therefore, a lower delta hedge ratio is necessary.

However, convertible bonds that trade at a high conversion act more like fixed income securities and therefore have more interest rate exposure than those with more equity exposure. This risk must be managed by selling interest rate futures, interest rate swaps, or other bonds. Furthermore, it should be noted that the hedging ratios for equity and interest rate risk are not static; they change as the value of the underlying equity changes and as interest rates change. Therefore, the hedge fund manager must continually adjust his hedge ratios to ensure that the arbitrage remains intact.

If this all sounds complicated, it is, but that is how hedge fund managers make money. They use sophisticated option-pricing models and interest rate models to keep track of all of the moving parts associated with convertible bonds. Hedge fund managers make arbitrage profits by identifying pricing discrepancies between the convertible bond and its component parts, and then continually monitoring these component parts for any change in their relationship.

Consider the following example: A hedge fund manager purchases 10 convertible bonds with a par value of $1,000, a coupon of 7.5%, and a market price of $900. The conversion ratio for the bonds is 20. The conversion ratio is based on the current price of the underlying stock, $45, and the current price of the convertible bond. The delta, or hedge, ratio for the bonds is 0.5. Therefore, to hedge the equity exposure in the convertible bond, the hedge fund manager must short the following shares of underlying stock:

| 10 Bonds × 20 Conversion ratio × 0.5 Hedge ratio |

| = 100 Shares of stock |

To establish the arbitrage, the hedge fund manager purchases 10 convertible bonds and sells 100 shares of stock. With the equity exposure hedged, the convertible bond is transformed into a traditional fixed income instrument with a 7.5% coupon.

Additionally, the hedge fund manager earns interest on the cash proceeds received from the short sale of stock. This is known as the "short rebate." The cash proceeds remain with the hedge fund manager's prime broker, but the hedge fund manager is entitled to the interest earned on the cash balance from the short sale (a rebate). (The short rebate is negotiated between the hedge fund manager and the prime broker. Typically, large, well-established hedge fund managers receive a larger short rebate.) We assume that the hedge fund manager receives a short rebate of 4.5%. Therefore, if the hedge fund manager holds the convertible arbitrage position for one year, he expects to earn interest not only from his long bond position, but also from his short stock position.

The catch to this arbitrage is that the price of the underlying stock may change as well as the price of the bond. Assume the price of the stock increases to $47 and the price of the convertible bond increases to $920. If the hedge fund manager does not adjust the hedge ratio during the holding period, the total return for this arbitrage will be:

Appreciation of bond price: | 10 × ($920-$900) | = | $200 |

Appreciation of stock price: | 100 × ($45-$47) | = | -$200 |

Interest on bonds: | 10 × $1,000 × 7.5% | = | $750 |

Short rebate: | 100 × $45 × 4.5% | = | $202.50 |

Total: | $952.50 |

If the hedge fund manager paid for the 10 bonds without using any leverage, the holding period return is

| $952.50 ÷ $9,000 = 10.58% |

Suppose the underlying stock price declined from $45 to $43, and the convertible bonds declined in value from $900 to $880. The hedge fund manager would then earn:

Depreciation of bond price: | 10 × ($880 - $900) | = | -$200 |

Depreciation of stock price: | 100 × ($45 - $43) | = | $200 |

Interest on bonds: | 10 × $1,000 × 7.5% = | = | $750 |

Short rebate: | 100 × $45 × 4.5% | = | $202.50 |

Total | $952.50 |

What this example demonstrates is that with the proper delta or hedge ratio in place, the convertible arbitrage manager should be insulated from movements in the underlying stock price so that the expected return should be the same regardless of whether the stock price goes up or goes down.

However, suppose that the hedge fund manager purchased the convertible bonds with $4,500 of initial capital and $4,500 of borrowed money. We further assume that the hedge fund manager borrows the additional investment capital from his prime broker at a prime rate of 6%.

Our analysis of the total return is then:

Appreciation of bond price: | 10 × ($920-$900) | = | $200 |

Appreciation of stock price: | 100 × ($47-$45) | = | -$200 |

Interest on bonds: | 10 × $1,000 × 7.5% | = | $750 |

Short rebate: | 100 × $45 × 4.5% | = | $202.5 |

Interest on borrowing: | 6% × $4,500 | = | -$270 |

Total: | $682.5 |

And the total return on capital is

The amount of leverage used in convertible arbitrage will vary with the size of the long positions and the objectives of the portfolio. Yet, in the preceding example, we can see how using a conservative leverage ratio of 2:1 in the purchase of the convertible bonds added almost 500 basis points of return to the strategy and earned a total return equal to twice that of the convertible bond coupon rate.

It is easy to see why hedge fund managers are tempted to use leverage. Hedge fund managers earn incentive fees on every additional basis point of return they earn. Furthermore, even though leverage is a two-edged sword—it can magnify losses as well as gains—hedge fund managers bear no loss if the use of leverage turns against them. In other words, hedge fund managers have everything to gain by applying leverage, but nothing to lose.

Leverage is also inherent in the shorting strategy because the underlying short equity position must be borrowed. Convertible arbitrage leverage can range from two to six times the amount of invested capital. This may seem significant, but it is lower than other forms of arbitrage.

Convertible bonds earn returns for taking on exposure to a number of risks such as (1) liquidity (convertible bonds are typically issued as private securities); (2) credit risk (convertible bonds are usually issued by less than investment grade companies); (3) event risk (the company may be downgraded or declare bankruptcy); (4) interest rate risk (as a bond it is exposed to interest rate risk); (5) negative convexity (most convertible bonds are callable); and (6) model risk (it is complex to model all of the moving parts associated with a convertible bond). These events are magnified only when leverage is applied.

Since convertible bond managers hedge away the equity risk through delta-neutral hedging, we should see little impact from the U.S. stock market. In addition, for undertaking all of the risks listed above, convertible bond arbitrage managers should earn a return premium to U.S. Treasury bonds.

Market Neutral

Market-neutral hedge funds also go long and short the market. The difference is that they maintain integrated portfolios, which are designed to neutralize market risk.

This means being neutral to the general stock market as well as having neutral risk exposures across industries. Security selection is all that matters.

Market-neutral hedge fund managers generally apply the rule of one alpha (see Jacobs and Levy, 1995). This means that they build an integrated portfolio designed to produce only one source of alpha. This is distinct from equity long/short managers that build two separate portfolios: one long and one short, with two sources of alpha. The idea of integrated portfolio construction is to neutralize market and industry risk and concentrate purely on stock selection. In other words, there is no beta risk in the portfolio with respect to either the broad stock market or any industry. Only stock selection, or alpha, should remain.

Market-neutral hedge fund managers generally hold equal positions of long and short stock positions. Therefore, the manager is dollar neutral; there is no net exposure to the market either on the long side or on the short side. Additionally, market-neutral managers generally apply no leverage because there is no market exposure to leverage. However, some leverage is always inherent when stocks are borrowed and shorted. Nonetheless, the nature of this strategy is that it does not have credit risk.

Generally, market-neutral managers follow a three-step procedure in their strategy. The first step is to build an initial screen of "investable" stocks. These are stocks traded on the manager's local exchange, with sufficient liquidity so as to be able to enter and exit positions quickly, and with sufficient float so that the stock may be borrowed from the hedge fund manager's prime broker for short positions. Additionally, the hedge fund manager may limit his universe to a capitalization segment of the equity universe such as the midcap range.

Second, the hedge fund manager typically builds factor models. These models are often known as "alpha engines." Their purpose is to find those financial variables that influence stock prices. These are bottom-up models that concentrate solely on corporate financial information as opposed to macroeconomic data. This is the source of the manager's skill—his stock-selection ability.

The last step is portfolio construction. The hedge fund manager will use a computer program to construct his portfolio in such a way that it is neutral to the market as well as across industries. The hedge fund manager may use a commercial "optimizer"—computer software designed to measure exposure to the market and produce a trade list for execution based on a manager's desired exposure to the market—or he may use his own computer algorithms to measure and neutralize risk.

Most market-neutral managers use optimizers to neutralize market and industry exposure. However, more sophisticated optimizers attempt to keep the portfolio neutral to several risk factors. These include size, book to value, price/earnings ratios, and market price to book value ratios. The idea is to have no intended or unintended risk exposures that might compromise the portfolio's neutrality.

We have more to say about transparency in our chapters regarding the selection of hedge fund managers and whether the hedge fund industry should be institutionalized. For now, it is sufficient to point out that black boxes tend to be problematic for investors.

We would expect market-neutral managers to produce returns independent of the general market (they are neutral to the market).

Statistical Arbitrage

A close cousin to equity market-neutral hedge fund managers is statistical arbitrage. The key difference is the amount of quantitative input. While equity market neutral is based more on fundamental research, statistical arbitrage is driven purely by quantitative factor models.

These managers use mathematical analysis to review past company performance in light of several quantitative factors. For instance, these managers may build regression models to determine the impact of market price to book value (price/book ratio) on companies across the universe of stocks as well as different market segments or economic sectors. Or they may analyze changes in dividend yields on stock price performance.

These are linear and quadratic regression equations designed to identify those economic factors that consistently have an impact on share prices. This process is very similar to that discussed with respect to equity long/short hedge fund managers. Indeed, the two strategies are very similar in their stock-selection methods. The difference is that equity long/short managers tend to have a net long exposure to the market while market-neutral managers have no exposure.

Typically, these managers build multifactor models, both linear and quadratic, to identify those economic factors that have a consistent impact on share prices. A key part of building their alpha engines is to apply the quantitative model on prior stock price performance to see if there is any predictive power in determining whether the stock of a particular company will rise or fall. If the model proves successful on historical data, the hedge fund manager will then conduct an "out of sample" test of the model. This involves testing the model on a subset of historical data that was not included in the model-building phase.

If a hedge fund identifies a successful quantitative strategy, it will apply its model mechanically. Buy and sell orders will be generated by the model and submitted to the order desk. In practice, the hedge fund manager will put limits on its model such as the maximum short exposure allowed or the maximum amount of capital that may be committed to any one stock position. In addition, quantitative hedge fund managers usually build in some qualitative oversight to ensure that the model is operating consistently.

Statistical arbitrage programs tend to be labeled black boxes. This is a term for sophisticated computer algorithms that lack transparency. The lack of transparency associated with these investment strategies comes in two forms. First, hedge fund managers, by nature, are secretive. They are reluctant to reveal their proprietary trading programs. Second, even if a hedge fund manager were to reveal his proprietary computer algorithms, these algorithms are often so sophisticated and complicated that they are difficult to comprehend.

Note that this strategy does not share in the large up-and-down cycles of the stock market. It earns a steady return, not as great as the stock market, but in excess of U.S. Treasuries. Remember, the goal of this strategy is to neutralize market risk and to profit on small price discrepancies between stocks in the same industry or sector. Consistent profits are the key; large bets are avoided.

Relative-Value Arbitrage

Relative-value arbitrage might be better named the smorgasbord of arbitrage. This is because relative-value hedge fund managers are catholic in their investment strategies; they invest across the universe of arbitrage strategies. The best known of these managers was Long-Term Capital Management. Once the story of LTCM unfolded, it was clear that their trading strategies involved merger arbitrage, fixed income arbitrage, volatility arbitrage, stub trading, and convertible arbitrage.

In general, the strategy of relative value managers is to invest in spread trades: the simultaneous purchase of one security and the sale of another when the economic relationship between the two securities (the "spread") has become mispriced. The mispricing may be based on historical averages or mathematical equations. In either case, the relative arbitrage manager purchases the security that is "cheap" and sells the security that is "rich." It is called relative-value arbitrage because the cheapness or richness of a security is determined relative to a second security. Consequently, relative-value managers do not take directional bets on the financial markets. Instead, they take focused bets on the pricing relationship between two securities.

Relative-value managers attempt to remove the influence of the financial markets from their investment strategies. This is made easy by the fact that they simultaneously buy and sell similar securities. Therefore, the market risk embedded in each security should cancel out. Any residual risk can be neutralized through the use of options or futures. What is left is pure security selection: the purchase of those securities that are relatively cheap and the sale of those securities that are relatively rich. Relative-value managers earn a profit when the spread between the two securities returns to normal. They then unwind their positions and collect their profit.

We have already discussed fixed income arbitrage, convertible arbitrage and statistical arbitrage. Two other popular forms of relative-value arbitrage are stub trading and volatility arbitrage.

Stub trading is an equity-based strategy. Frequently, companies acquire a majority stake in another company, but their stock price does not fully reflect their interest in the acquired company. As an example, consider Company A, whose stock is trading at $50. Company A owns a majority stake in Company B, whose remaining outstanding stock, or stub, is trading at $40. The value of Company A should be the combination of its own operations, estimated at $45 a share, plus its majority stake in Company B's operations, estimated at $8 a share. Therefore, Company A's share price is undervalued relative to the value that Company B should contribute to Company A's share price. The share price of Company A should be about $53, but instead, it is trading at $50. The investment strategy would be to purchase Company A's stock and sell the appropriate ratio of Company B's stock.

Let us assume that Company A's ownership in Company B contributes to 20% of Company A's consolidated operating income. Therefore, the operations of Company B should contribute one fifth to Company A's share price. A proper hedging ratio would be four shares of Company A's stock to one share of Company B's stock.

The arbitrage strategy is:

| Buy four shares of Company A stock at 4 × $50 = $200 |

| Sell one share of Company B stock at 1 × $40 = $40 |

The relative-value manager is now long Company A stock and hedged against the fluctuation of Company B's stock. Let us assume that over three months, the share price of Company B increases to $42 a share, the value of Company A's operations remains constant at $45, but now the shares of Company A correctly reflect the contribution of Company B's operations. The value of the position will be:

Value of Company A's operations: | 4 × $45 | = | $180 |

Value of Company B's operations | 4 × $42 × 20% | = | $33.6 |

Loss on short of Company B stock | 1 × ($40 - $42) | = | -$2 |

Short rebate on Company B stock | 1 × $40 × 4.5% × 3/12 | = | $0.45 |

Total: | $212.05 |

The initial invested capital was $200 for a gain of $12.05 or 6.02% over three months. Suppose the stock of Company B had declined to $30, but Company B's operations were properly valued in Company A's share price. The position value would be:

Value of Company A's operations: | 4 × $45 | = | $180 |

Value of Company B's operations: | 4 × $30 × 20% | = | $24 |

Gain on short of Company B's stock: | 1 × ($40 - $30) | = | $10 |

Short rebate on Company B's stock: | 1 × $40 × 4.5% × 3/12 | = | $0.045 |

Total: | $214.45 |

The initial invested capital was $200 for a gain of $14.45 or 7.22% over three months. Stub trading is not arbitrage. Although the value of Company B's stock has been hedged, the hedge fund manager must still hold its position in Company A's stock until the market recognizes its proper value.

Volatility arbitrage involves options and warrant trading. Option prices contain an implied number for volatility. That is, it is possible to observe the market price of an option and back out the value of volatility implied in the current price using various option pricing models. The arbitrageur can then compare options on the same underlying stock to determine if the volatility implied by their prices are the same.

The implied volatility derived from option pricing models should represent the expected volatility of the underlying stock that will be realized over the life of the option. Therefore, two options on the same underlying stock should have the same implied volatility. If they do not, an arbitrage opportunity may be available. Additionally, if the implied volatility is significantly different from the historical volatility of the underlying stock, then relative-value arbitrageurs expect the implied volatility will revert back to its historical average.

Volatility arbitrage generally is applied in one of two models. The first is a mean reversion model. This model compares the implied volatility from current option prices to the historical volatility of the underlying security with the expectation that the volatility reflected in the current option price will revert to its historical average and the option price will adjust accordingly.

A second volatility arbitrage model applies a statistical technique called generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH). GARCH models use prior data points of realized volatility to forecast future volatility. The GARCH forecast is then compared to the volatility implied in current option prices.

Both models are designed to allow hedge fund managers to determine which options are priced "cheap" versus "rich." Once again, relative-value managers sell those options that are rich based on the implied volatility relative to the historical volatility and buy those options with cheap volatility relative to historical volatility.

Along the lines of the smorgasbord comment for relative-value hedge funds, these strategies have the broadest mandate across the financial, commodity, and futures markets. These all-encompassing mandates can lead to specific bets on currencies or stocks as well as a well-diversified portfolio.

Global Macro

As their name implies, global macro hedge funds take a macroeconomic approach on a global basis in their investment strategy. These are top-down managers who invest opportunistically across financial markets, currencies, national borders, and commodities. They take large positions depending on the hedge fund manager's forecast of changes in interest rates, currency movements, monetary policies, and macroeconomic indicators.

Global macro managers have the broadest investment universe. They are not limited by market segment or industry sector, nor by geographic region, financial market, or currency. Global macro also may invest in commodities. In fact, a fund of global macro hedge funds offers the greatest diversification of investment strategies.

Global macro hedge funds tend to have large amounts of investor capital. This is necessary to execute their macro-economic strategies. In addition, they may apply leverage to increase the size of their macro bets. As a result, global macro hedge funds tend to receive the greatest attention and publicity in the financial markets.

The best known of these hedge funds was the Quantum Hedge Fund managed by George Soros. It is well documented that this fund made significant gains in 1992 by betting that the British pound would devalue (which it did). This fund was also accused of contributing to the "Asian Contagion" in the fall of 1997 when the government of Thailand devalued its currency, the baht, triggering a domino effect in currency movements throughout Southeast Asia.

In recent times, however, global macro hedge funds have fallen on hard times. One reason is that many global macro-hedge funds were hurt by the Russian bond default in August 1998 and the bursting of the technology bubble in March 2000. These two events caused large losses for the global macro hedge funds.

A second reason, as indicated above, is that global macro hedge funds had the broadest investment mandate of any hedge fund strategy. The ability to invest widely across currencies, commodities, financial markets, geographic borders, and time zones is a two-edged sword. On the one hand, it allows global macro hedge funds the widest universe in which to implement their strategies. On the other hand, it lacks focus. As more institutional investors have moved into the hedge fund marketplace, they have demanded greater investment focus as opposed to free investment rein.

Fund of Funds

Finally, we come to hedge fund of funds. These are hedge fund managers that invest their capital in other hedge funds. These managers practice tactical asset allocation; reallocating capital across hedge fund strategies when they believe that certain hedge fund strategies will do better than others. For example, during the bear market of 2000 to 2002, short-selling strategies performed the best of all hedge fund categories. Not surprisingly, fund of fund managers allocated a significant portion of their portfolios to short sellers during the recent bear market. Other strategies that are popular in fund of funds are global macro, fixed income arbitrage, convertible arbitrage, statistical arbitrage, equity long/short, and event driven.

One drawback on fund of funds is the double layer of fees. Investors in hedge fund of funds typically pay a management fee plus profit-sharing fees to the hedge fund of funds managers in addition to the management and incentive fees that must be absorbed from the underlying hedge fund managers. This double layer of fees makes it difficult for fund of fund managers to outperform some of the more aggressive individual hedge fund strategies. However, the trade-off is better risk control from a diversified portfolio.

A considerable amount of research has been dedicated to examining the return potential of several hedge fund styles. Additionally, a number of studies have considered hedge funds within a portfolio context, that is, hedge funds blended with other asset classes.

The body of research on hedge funds demonstrates two key qualifications for hedge funds. First, over the time period of 1989 to 2000, the returns to hedge funds were positive. The highest returns were achieved by global macro hedge funds, and the lowest returns were achieved by short selling hedge funds. Not all categories of hedge funds beat the Standard and Poor's (S&P) 500. However, in many cases, the volatility associated with hedge fund returns was lower than that of the S&P 500, resulting in higher Sharpe ratios.

Second, the empirical research demonstrates that hedge funds provide good diversification benefits. In other words, hedge funds do, in fact, hedge other financial assets. Correlation coefficients with the S&P 500 range from −0.7 for short selling hedge funds to 0.83 for opportunistic hedge funds investing in the U.S. markets. The less-than-perfect positive correlation with financial assets indicates that hedge funds can expand the efficient frontier for asset managers.

In summary, the recent research on hedge funds indicates consistent, positive performance with low correlation with traditional asset classes. The conclusion is that hedge funds can expand the investment opportunity set for investors, offering both return enhancement as well as diversification benefits.

This is the age-old question with respect to all asset managers, not just hedge funds: Can the manager repeat her good performance? This issue, though, is particularly acute for the hedge fund marketplace for two reasons. First, hedge fund managers often claim that the source of their returns is "skill based" rather than dependent on general financial market conditions. Second, hedge fund managers tend to have shorter track records than traditional money managers.

Unfortunately, the evidence regarding hedge fund performance persistence is mixed. The few empirical studies that have addressed this issue have provided inconclusive evidence whether hedge fund managers can produce enduring results. Part of the reason for the mixed results is the short track records of most hedge fund managers. A three-year or five-year track record is too short a period of time to be able to estimate an accurate expected return or risk associated with that manager.

In addition, the skill-based claim of hedge fund managers makes it more difficult to assess their performance relative to a benchmark. Without a benchmark index for comparison, it is difficult to determine whether a hedge fund manager has outperformed or underperformed her performance "bogey." As a result, the persistence of hedge fund manager performance will remain an open issue until manager databases with longer performance track records can be developed.

The preceding discussion demonstrates that hedge funds can expand the investment opportunity set for investors. The question now becomes: What is to be accomplished by the hedge fund investment program? The strategy may be simply a search for an additional source of return. Conversely it may be for risk management purposes. Whatever its purpose, an investment plan for hedge funds may consider one of three strategies. Hedge funds may be selected on an opportunistic basis, as a hedge fund of funds, or as an absolute-return strategy. A fourth possible strategy is a joint venture where an investor provides seed capital and investment capital for a new hedge fund manager. The investor receives professional hedge fund management plus a "piece of the action."

The term hedge fund can be misleading. Hedge funds do not necessarily have to hedge an investment portfolio. Rather, they can be used to expand the investment opportunity set. This is the opportunistic nature of hedge funds—they can provide an investor with new investment opportunities that she cannot otherwise obtain through traditional long-only investments.

There are several ways hedge funds can be opportunistic. First, many hedge fund managers can add value to an existing investment portfolio through specialization in a sector or in a market strategy. These managers do not contribute portable alpha. Instead, they contribute above market returns through the application of superior skill or knowledge to a narrow market or strategy.

Consider a portfolio manager whose particular expertise is the biotechnology industry. She has followed this industry for years and has developed a superior information set to identify winners and losers. On the long-only side, the manager purchases those stocks that she believes will increase in value and avoids those biotech stocks she believes will decline in value. However, this strategy does not utilize her superior information set to its fullest advantage. The ability to go both long and short biotech stocks in a hedge fund is the only way to maximize the value of the manager's information set. Therefore, a biotech hedge fund provides a new opportunity: the ability to extract value on both the long side and the short side of the biotech market.

The goal of this strategy is to identify the best managers in a specific economic sector or specific market segment that complements the existing investment portfolio. These managers are used to enhance the risk and return profile of an existing portfolio, rather than hedge it.

Opportunistic hedge funds tend to have a benchmark. Take the example of the biotech long/short hedge fund. An appropriate benchmark would be the AMEX Biotech Index that contains 17 biotechnology companies. Alternatively, if the investor believed that the biotech sector will outperform the general stock market, she could use a broad-based stock index such as the S&P 500 for the benchmark. The point is that opportunistic hedge funds are not absolute-return vehicles (discussed later). Their performance can be measured relative to a benchmark.

As another example, most institutional investors have a broad equity portfolio. This portfolio may include an index fund, external value and growth managers, and possibly, private equity investments. However, along the spectrum of this equity portfolio, there may be gaps in its investment lineup. For instance, many hedge funds combine late-stage private investments with public securities. These hybrid funds are a natural extension of an institution's investment portfolio because they bridge the gap between private equity and index funds. Therefore, a new opportunity is identified: the ability to blend private equity and public securities within one investment strategy.

Alternative "assets" are really alternative investment strategies, and these alternative strategies are used to expand the investment opportunity set rather than hedge it. In summary, hedge funds may be selected not necessarily to reduce the risk of an existing investment portfolio, but instead, to complement its risk and return profile. Opportunistic investing is designed to select hedge fund managers that can enhance certain portions of a broader portfolio.

Another way to consider opportunistic hedge fund investments is that they are finished products because their investment strategy or market segment complements an institutional investor's existing asset allocation. In other words, these hybrid funds can plug the gaps of an existing portfolio. No further work is necessary on the part of the institution because the investment opportunity set has been expanded by the addition of the hybrid product. These "gaps" may be in domestic equity, fixed income, or international investments. Additionally, because opportunistic hedge funds are finished products, it makes it easier to establish performance benchmarks.

Constructing an opportunistic portfolio of hedge funds will depend on the constraints under which such a program operates. For example, if an investor's hedge fund program is not limited in scope or style, then diversification across a broad range of hedge fund styles would be appropriate. If, however, the hedge fund program is limited in scope to, for instance, expanding the equity investment opportunity set, the choices will be less diversified across strategies. Table 53.1 demonstrates these two choices.

A hedge fund of funds is an investment in a group of hedge funds, from 5 to more than 20. The purpose of a hedge fund of funds is to reduce the idiosyncratic risk of any one hedge fund manager. In other words, there is safety in numbers. This is simply the modern portfolio theory (MPT) applied to the hedge fund marketplace. Diversification is one of the founding principles of MPT, and it is as applicable to hedge funds as it is to stocks and bonds.

Table 53.1. Implementing an Opportunistic Hedge Fund Strategy

Diversified Hedge Fund Portfolio | Equity-Based Hedge Fund Portfolio |

|---|---|

Equity long/short | Equity long/short |

Short selling | Short selling |

Market neutral | Market neutral |

Merger arbitrage | Merger arbitrage |

Event driven | Event driven |

Convertible arbitrage | Convertible arbitrage |

Global macro | |

Fixed income arbitrage | |

Relative-value arbitrage | |

Market timers |

Hedge funds are often described as absolute-return products. This term comes from the skill-based nature of the industry. Hedge fund managers generally claim that their investment returns are derived from their skill at security selection rather than that of broad asset classes. This is due to the fact that most hedge fund managers build concentrated portfolios of relatively few investment positions and do not attempt to track a stock or bond index. The work of Fung and Hsieh (1997) shows that hedge funds generate a return distribution that is very different from mutual funds.

Further, given the generally unregulated waters in which hedge fund managers operate, they have greater flexibility in their trading style and execution than traditional long-only managers. This flexibility provides a greater probability that a hedge fund manager will reach his return targets. As a result, hedge funds have often been described as absolute-return vehicles that target a specific annual return regardless of what performance might be found among market indices. In other words, hedge fund managers target an absolute return rather than determine their performance relative to an index.

All traditional long-only managers are benchmarked to some passive index. The nature of benchmarking is such that it forces the manager to focus on his benchmark and his tracking error associated with that benchmark. This focus on benchmarking leads traditional active managers to commit a large portion their portfolios to tracking their benchmark. The necessity to consider the impact of every trade on the portfolio's tracking error relative to its assigned benchmark reduces the flexibility of the investment manager.

In addition, long-only active managers are constrained in their ability to short securities. They may only "go short" a security up to its weight in the benchmark index. If the security is only a small part of the index, the manager's efforts to short the stock will be further constrained. The inability to short a security beyond its benchmark weight deprives an active manager of a significant amount of the mispricing in the marketplace. Furthermore, not only are long-only managers unable to take advantage of overpriced securities, but they also cannot fully take advantage of underpriced securities because they cannot generate the necessary short positions to balance the overweights with respect to underpriced securities.

The flexibility of hedge fund managers allows them to go both long and short without benchmark constraints. This allows them to set a target rate of return or an "absolute return."

Specific parameters must be set for an absolute-return program. These parameters will direct how the hedge fund program is constructed and operated and should include risk and return targets as well as the type of hedge fund strategies that may be selected. Absolute-return parameters should operate at two levels: that of the individual hedge fund manager and for the overall hedge fund program. The investor sets target return ranges for each hedge fund manager but sets a specific target return level for the absolute return program. The parameters for the individual managers may be different than that for the program. For example, acceptable levels of volatility for individual hedge fund managers may be greater than that for the program.

The program parameters for the hedge fund managers may be based on such factors as volatility, expected return, types of instruments traded, leverage, and historical drawdown. Other qualitative factors may be included such as length of track record, periodic liquidity, minimum investment, and assets under management. Liquidity is particularly important because an investor needs to know with certainty her time-frame for cashing out of an absolute-return program if hedge fund returns turn sour.

Table 53.2 demonstrates an absolute-return program strategy. Notice that the return for the portfolio has a specific target rate of 15%, while for the individual hedge funds the return range is 10% to 25%. Also, the absolute-return portfolio has a target level for risk and drawdowns, while for the individual hedge funds, a range is acceptable.

However, certain parameters are synchronized. Liquidity, for instance, must be the same for both the absolute-return portfolio and that of the individual hedge fund managers. The reason is that a range of liquidity is not acceptable if the investor wishes to liquidate her portfolio. She must be able to cash out of each hedge fund within the same time-frame as that established for the portfolio.

Table 53.2. An Absolute-Return Strategy

Absolute-Return Portfolio | Individual Hedge Fund Managers |

|---|---|

Target return: 15% | Expected return: 10% to 25% |

Target risk: 7% | Target risk: 5% to 15% |

Largest acceptable draw-down: 10% | Largest drawdown: 10% to 20% |

Liquidity: Semiannual | Liquidity: Semiannual |

Hedge fund style: equity based | Hedge fund style: equity L/S, market neutral, merger arbitrage, short selling, event driven, convertible arbitrage |

Length of track record: 3 years | |

Minimum track record: 3 years |

The hedge fund industry is still relatively new. Most of the academic research on hedge funds was conducted during the 1990s. As a result, for most hedge fund managers, a two- to three-year track record is considered long term. In fact, Park, Brown, and Goetzmann (2001) find that the attrition rate in the hedge fund industry is about 15% per year and that the half-life for hedge funds is about 2.5 years. Liang (2001) documents an attrition rate of 8.54% per year for hedge funds. Weisman and Abernathy (2000) indicate that relying on a hedge fund manager's past performance history can lead to disappointing investment results. Consequently, performance history, while useful, cannot be relied upon solely in selecting a hedge fund manager.

Beyond performance numbers, there are three fundamental questions that every hedge fund manager should answer during the initial screening process. The answers to these three questions are critical to understanding the nature of the hedge fund manager's investment program. The three questions are:

What is the investment objective of the hedge fund?

What is the investment process of the hedge fund manager?

What makes the hedge fund manager so smart?

A hedge fund manager should have a clear and concise statement of its investment objective. Second, the hedge fund manager should identify its investment process. For instance, is it quantitatively or qualitatively based? Last, the hedge fund manager must demonstrate that he or she is smarter than other money managers.

The questions presented are threshold issues. These questions are screening tools designed to reduce an initial universe of hedge fund managers down to a select pool of potential investments. They are not, however, a substitute for a thorough due diligence review.

The question of a hedge fund manager's investment objective can be broken down into three questions:

In which markets does the hedge fund manager invest?

What is the hedge fund manager's general investment strategy?

What is the hedge fund manager's benchmark, if any?