FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

STEVEN V. MANN, PhD

Professor of Finance, Moore School of Business, University of South Carolina

Abstract: Access to short-term financing and the ability to borrow securities to cover short positions are essential elements to a liquid, well-functioning bond market. Repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements are mechanisms used by dealers to accomplish these needs. Repurchase agreements occupy a central position in the money market and provide a relatively safe investment opportunity for short-term investors. Structured repurchase agreements introduce variations on the basic agreement and are designed to accommodate specialized clienteles of users. Similarly, dollar rolls developed in the mortgage-backed securities market because of the need to borrow these more complicated securities to cover short positions.

Keywords: repurchase agreement, reverse repurchase agreement, repo rate, overnight repo, repo term, repo margin, collateral, delivered out, hold-in-custody (HIC) repo, triparty repo, general collateral, special collateral, buy/sell-back agreement, structured repurchase agreements, dollar roll, pass-through, TBA (to be announced), collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO), forward drop, prepayment speed

One of the largest segments of the money markets world-wide is the market in repurchase agreements or repos. A most efficient mechanism by which to finance bond positions, repo transactions enable market makers to take long and short positions in a flexible manner, buying and selling according to customer demand on a relatively small capital base. In addition, repos are used extensively to facilitate hedging and speculation. Repo is also a flexible and relatively safe investment opportunity for short-term investors. The ability to execute repo is particularly important to firms in less developed countries who might not have access to a deposit base. Moreover, in countries where no repo market exists, funding is in the form of unsecured lines of credit from the banking system which is restrictive for some market participants. A liquid repo market is often cited as a key ingredient of a liquid bond market. In the United States, repo is a well-established money market instrument and is developing in a similar way in Europe and Asia.

A major sector of the bond market in the United States is the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market. A specialized type of collateralized loan is used in the mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market because of the characteristics of these securities and the need of dealers to borrow these securities to cover short positions. This arrangement is called a dollar roll and can be thought of as a specialized form of a reverse repurchase agreement with pass-through securities serving as collateral. A dollar roll is so named because dealers are said to "roll in" securities they borrow and "roll out" securities when returning the securities to the investor.

In this chapter, we discuss repurchase agreements and dollar roll agreements.

A repurchase agreement or "repo" is the sale of a security with a commitment by the seller to buy the same security back from the purchaser at a specified price at a designated future date. For example, a dealer who owns a 10-year U.S. Treasury note might agree to sell this security (the "seller") to a mutual fund (the "buyer") for cash today while simultaneously agreeing to buy the same 10-year note back at a certain date in the future (or in some cases on demand) for a predetermined price. The price at which the seller must subsequently repurchase the security is called the repurchase price and the date that the security must be repurchased is called the repurchase date. Simply put, a repurchase agreement is a collateralized loan where the collateral is the security that is sold and subsequently repurchased. One party (the "seller") is borrowing money and providing collateral for the loan; the other party (the "buyer") is lending money and accepting a security as collateral for the loan. To the borrower, the advantage of a repurchase agreement is that the short-term borrowing rate is lower than the cost of bank financing, as we will see shortly. To the lender, the repo market offers an attractive yield on a short-term secured transaction that is highly liquid. This latter aspect is the focus of this section.

Suppose that on September 28, 2006, a government securities dealer purchases a 4.875% coupon on-the-run 10-year U.S. Treasury note that matures on August 15, 2016. The face amount of the position is $1 million, and the note's full price (that is, flat price plus the accrued interest) is $1,025,672.55. Further, suppose the dealer wants to hold the position until the next business day, which is Friday, September 29,2006. Where does the dealer obtain the funds to finance this position?

Of course, the dealer can finance the position with its own funds or by borrowing from a bank. Typically, though, the dealer uses a repurchase agreement or "repo" to obtain financing. In the repo market, the dealer can use the purchased Treasury note as collateral for a loan. The term of the loan and the interest rate a dealer agrees to pay are specified. The interest rate is called the repo rate.

When the term of a repo is one day, it is called an overnight repo. Conversely, a loan for more than one day is called a term repo. The transaction is referred to as a repurchase agreement because it calls for the security's sale and its repurchase at a future date. Both the sale price and the purchase price are specified in the agreement. The difference between the purchase (repurchase) price and the sale price is the loan's dollar interest cost.

Let us return to the dealer who needs to finance a long position in the Treasury note for one day. The settlement date is the day that the collateral must be delivered and the money lent to initiate the transaction, which, in our example, is September 28, 2006. Likewise, the termination date of the repo agreement is September 29. At this point, we need to address who might serve as the dealer's counterparty (that is, the lender of funds) in this transaction. Suppose that one of the dealer's customers has excess funds in the amount of $1,025,672.55 and is the amount loaned in the repo agreement. Accordingly, on September 28, 2006, the dealer would agree to deliver ("sell") $1,025,672.55 worth of 10-year U.S. Treasury notes to the customer and buy the same 10-year notes back for an amount determined by the repo rate the next business day on September 29, 2006. (We are assuming in this example that the borrower will provide collateral that is equal in value to the money that is loaned. In practice, lenders usually require borrowers to provide collateral in excess of the value of money that is loaned. We will illustrate how this is accomplished when we discuss repo margins.)

Suppose the repo rate is this transaction is 5.15%. Then, as will be explained below, the dealer would agree to deliver the 10-year Treasury notes for $1,025,819.28 the next day. The $146.73 between the "sale" price of $1,025,672.55 and the repurchase price of $1,025,819.28 is the dollar cost of the financing.

Repo Interest

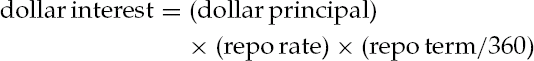

The following formula is used to calculate the dollar interest on a repo transaction:

In our illustration, using a repo rate of 5.15% and a repo term of one day, the dollar interest is $146.73 as shown below:

The advantage to the dealer of using the repo market for borrowing on a short-term basis is that the rate is lower than the cost of bank financing for reasons explained shortly. From the customer's perspective (that is, the lender), the repo market offers an attractive yield on a short-term secured transaction that is highly liquid.

Reverse Repo and Market Jargon

In the illustration presented above, the dealer is using the repo market to obtain financing for a long position. The repo market can correspondingly be used to borrow securities. Securities are routinely borrowed for a number of reasons including opening a short position, the need to deliver securities against the exercise of a derivative contract, and the need to cover a failed transaction in the securities settlement system. Many arbitrage strategies involve the borrowing of securities (e.g., convertible bond arbitrage).

Suppose a government dealer established a short position in the 30-year Treasury bond one week ago and must now cover the position—namely, deliver the securities. The dealer accomplishes this task by engaging in a reverse repurchase agreement. In a reverse repo, the dealer agrees to buy securities at a specified price with a commitment to sell them back at a later date for another specified price. (Of course, the dealer eventually would have to buy the 30-year bonds in the market in order to cover its short position.) In this case, the dealer is making a collateralized loan to its customer. The customer is lending securities and borrowing funds obtained from the collateralized loan to create leverage.

There is a great deal of Wall Street jargon surrounding repo transactions. In order to decipher the terminology, remember that one party is lending money and accepting a security as collateral for the loan; the other party is borrowing money and providing collateral to borrow the money. By convention, whether the transaction is called a repo or a reverse repo is determined by viewing the transaction from the dealer's perspective. If the dealer is borrowing money from a customer and providing securities as collateral, the transaction is called a repo. If the dealer is borrowing securities (which serve as collateral) and lends money to a customer, the transaction is called a reverse repo.

When someone lends securities in order to receive cash (that is, borrow money), that party is said to be "reversing out" securities. Correspondingly, a party that lends money with the security as collateral for the loan is said to be "reversing in" securities.

The expressions "to repo securities" and "to do repo" are also commonly used. The former means that someone is going to finance securities using the securities as collateral; the latter means that the party is going to invest in a repo as a money market instrument.

Lastly, the expressions "selling collateral" and "buying collateral" are used to describe a party financing a security with a repo on the one hand, and lending on the basis of collateral on the other.

Types of Collateral

While in our illustration, we use a Treasury security as collateral, the collateral in a repo is not limited to government securities. Money market instruments, federal agency securities, and mortgage-backed securities are also used. In some specialized markets, even whole loans are used as collateral.

Just as in any borrowing/lending agreement, both parties in a repo transaction are exposed to credit risk. This is true even though there may be high-quality collateral underlying the repo transaction. Let us examine under which circumstances each counterparty is exposed to credit risk.

Suppose the dealer (that is, the borrower) defaults such that the Treasuries are not repurchased on the repurchase date. The investor gains control over the collateral and retains any income owed to the borrower. The risk is that Treasury yields have risen subsequent to the repo transaction such that the market value of collateral is worth less than the unpaid repurchase price. Conversely, suppose the investor (that is, the lender) defaults such that the investor fails to deliver the Treasuries on the repurchase date. The risk is that Treasury yields have fallen over the agreement's life such that the dealer now holds an amount of dollars worth less then the market value of collateral. In this instance, the investor is liable for any excess of the price paid by the dealer for replacement securities over the repurchase price.

Repo Margin

While both parties are exposed to credit risk in a repo transaction, the lender of funds is usually in the more vulnerable position. Accordingly, the repo is structured to reduce the lender's credit risk. Specifically, the amount lent should be less than the market value of the security used as collateral, thereby providing the lender some cushion should the collateral's market value decline. The amount by which the market value of the security used as collateral exceeds the value of the loan is called repo margin or "haircut." Repo margins vary from transaction to transaction and are negotiated between the counterparties based on factors such as the following: term of the repo agreement, quality of the collateral, creditworthiness of the counterparties, and the availability of the collateral. Minimum repo margins are set differently across firms and are based on models and/or guidelines created by their credit departments. Repo margin is generally between 1% and 3%. For borrowers of lower creditworthiness and/or when less liquid securities are used as collateral, the repo margin can be 10% or more.

To illustrate the role of the haircut in a repurchase agreement, let us once again return to the government securities dealer who purchases a 4.875% coupon, 10-year Treasury note and needs financing overnight. The face amount of the position is $1 million and the note's full price is $1,025,672.55.

When a haircut is included, the amount the counterparty is willing to lend is reduced by a given percentage of the security's market value. Suppose the collateral is 102% of the amount being lent. To determine the amount being lent, we divide the Treasury note's full price of $1,025,672.55 by 1.02 to obtain $1,005,561.33, which is the amount the counterparty will lend. Suppose the repo rate is 5.15%. As a result, the transaction is structured as follows. The dealer would agree to deliver to the 10-year Treasury notes for $1,005,561.33 and repurchase the same securities for $1,005,705.18 the next day. The $143.85 difference between the "sale" price of $1,005,561.33 and the repurchase price of $1,005,705.18 is the dollar interest on the financing. Using a repo rate of 5.15 and a repo term of one day, the dollar interest is calculated as shown below:

Marking the Collateral to Market

Another practice to limit credit risk is to mark the collateral to market on a regular basis. Marking a position to market means simply recording the position's value at its market value. When the market value changes by a certain percentage, the repo position is adjusted accordingly. For complex securities that do not trade frequently, there is considerable difficulty in obtaining a price at which to mark a position to market.

Delivery of the Collateral

One concern in structuring a repurchase agreement is delivery of the collateral to the lender. The most obvious procedure is for the borrower to actually deliver the collateral to the lender or to the cash lender's clearing agent. If this procedure is followed, the collateral is said to be delivered out. At the end of the repo term, the lender returns collateral to the borrower in exchange for the repurchase price (that is, the amount borrowed plus interest).

The drawback of this procedure is that it may be too expensive, particularly for short-term repos (e.g., overnight) owing to the costs associated with delivering the collateral. Indeed, the cost of delivery is factored into the repo rate of the transaction in that if delivery is required this translates into a lower repo rate paid by the borrower. If delivery of collateral is not required, an otherwise higher repo rate is paid. The risk to the lender of not taking actual possession of the collateral is that the borrower may sell the security or use the same security as collateral for a repo with another counterparty.

As an alternative to delivering out the collateral, the lender may agree to allow the borrower to hold the security in a segregated customer account. The lender still must bear the risk that the borrower may use the collateral fraudulently by offering it as collateral for another repo transaction. If the borrower of the cash does not deliver out the collateral, but instead holds it, then the transaction is called a hold-in-custody (HIC) repo. Despite the credit risk associated with a HIC repo, it is used in some transactions when the collateral is difficult to deliver (e.g., whole loans) or the transaction amount is relatively small and the lender of funds is comfortable with the borrower's reputation.

Investors participating in a HIC repo must ensure: (1) they transact only with dealers of good credit quality since an HIC repo may be perceived as an unsecured transaction and (2) the investor (that is, the lender of cash) receives a higher rate in order to compensate them for the higher credit risk involved. In the U.S. market, there have been cases where dealer firms that went into bankruptcy and defaulted on loans were found to have pledged the same collateral for multiple HIC transactions.

Another method for handling the collateral is for the borrower to deliver the collateral to the lender's custodial account at the borrower's clearing bank. The custodian then has possession of the collateral that it holds on the lender's behalf. This method reduces the cost of delivery because it is merely a transfer within the borrower's clearing bank. If, for example, a dealer enters into an overnight repo with Customer A, the next day the collateral is transferred back to the dealer. The dealer can then enter into a repo with Customer B for, say, five days without having to redeliver the collateral. The clearing bank simply establishes a custodian account for Customer B and holds the collateral in that account. In this type of repo transaction, the clearing bank is an agent to both parties. This specialized type of repo arrangement is called a triparty repo. For some regulated financial institutions (e.g., federally chartered credit unions), this is the only type of repo arrangement permitted.

Just as there is no single interest rate, there is not one repo rate. The repo rate varies from transaction to transaction depending on a number of factors: quality of the collateral, term of the repo, delivery requirement, availability of the collateral, and the prevailing federal funds rate.

Table 72.1 presents repo and reverse repo rates for maturities of one day, one week, two weeks, three weeks, one month, two months, and three months using U.S. Treasuries as collateral. These data are obtained from Bloomberg. Repo and reverse repo rates differ by maturity and type of collateral. Another pattern evident in these data is that repo rates are lower than the reverse repo rates when matched by collateral type and maturity. These repo (reverse repo) rates can viewed as the rates the dealer will borrow (lend) funds. Alternatively, repo (reverse repo) rates are prices at which dealers are willing to buy (sell) collateral. While a dealer firm primarily uses the repo market as a vehicle for financing its inventory and covering short positions, it will also use the repo market to run a "matched book." A dealer runs a matched book by simultaneously entering into a repo and a reverse repo for the same collateral with the same maturity. The dealer does so to capture the spread at which it enters into a repurchase agreement (that is, an agreement to borrow funds) and a reverse repurchase agreement (that is, an agreement to lend funds).

For example, suppose that a dealer enters into a term repo for one month with a money market mutual fund and a reverse repo with a corporate credit union for one month for which the collateral is identical. In this arrangement, the dealer is borrowing funds from the money market mutual fund and lending funds to the corporate credit union.

Table 72.1. Repo and Reverse Repo Rates

Maturity | Repo(%) | Reverse(%) |

|---|---|---|

1 day | 5.10 | 5.15 |

1 week | 5.06 | 5.11 |

2 weeks | 5.10 | 5.15 |

3 weeks | 5.10 | 5.15 |

1 month | 5.11 | 5.16 |

2 months | 5.14 | 5.19 |

3 months | 5.15 | 5.20 |

From Table 72.1, we find that the repo rate for a one-month repurchase agreement is 5.11% and the repo rate for the one-month reverse repurchase agreement is 5.16%. If these two positions are established simultaneously, then the dealer is borrowing at 5.11% and lending at 5.16% thereby locking in a spread of 5 basis points.

However, in practice, traders deliberately mismatch their books to take advantage of their expectations about the shape and level of the short-dated yield curve. The term matched book is therefore something of a misnomer in that most matched books are deliberately mismatched for this reason. Traders engage in positions to take advantage of (1) short-term interest rate movements and (2) anticipated demand and supply in the underlying bond.

The delivery requirement for collateral also affects the level of the repo rate. If delivery of the collateral to the lender is required, the repo rate will be lower. Conversely, if the collateral can be deposited with the bank of the borrower, a higher repo rate will be paid.

The more difficult it is to obtain the collateral, the lower the repo rate. To understand why this is so, remember that the borrower (or equivalently the seller of the collateral) has a security that lenders of cash want for whatever reason. (Perhaps the issue is in great demand to satisfy borrowing needs.) Such collateral is said to "on special." Collateral that does not share this characteristic is referred to as general collateral. The party that needs collateral that is "on special" will be willing to lend funds at a lower repo rate in order to obtain the collateral.

There are several factors contributing to the demand for special collateral. They include:

Government bond auctions—the bond to be issued is shorted by dealers in anticipation of new supply and due to client demand.

Outright short selling whether a deliberate position taken based on a trader's expectations or dealers shorting bonds to satisfy client demand.

Hedging including corporate bonds underwriters who short the relevant maturity benchmark government bond that the corporate bond is priced against.

Derivative trading such as basis trading creating a demand for a specific bond.

Buy-back or cancellation of debt at short notice.

Financial crises will also impact a particular security's "specialness." Specialness is defined the spread between the general collateral rate and the repo rate of a particular security. Michael Fleming found that the on-the-run 2-year note, 5-year note, and 30-year bond traded at an increased rate of specialness during the Asian financial crisis of 1998. In other words, the spread between the general collateral rate and the repo rates on these securities increased. Moreover, these spreads returned to more normal levels after the crisis ended (see Fleming (2000)).

While these factors determine the repo rate on a particular transaction, the federal funds rate determines the general level of repo rates. The repo rate generally will trade lower than the federal funds rate, because a repo involves collateralized borrowing while a federal funds transaction is unsecured borrowing.

As noted earlier in the chapter, there are a number of investment strategies in which an investor borrows funds to purchase securities. The investor's expectation is that the return earned by investing in the securities purchased with the borrowed funds will exceed the borrowing cost. The use of borrowed funds to obtain greater exposure to an asset than is possible by using only cash is called leveraging. In certain circumstances, a borrower of funds via a repo transaction can generate an arbitrage opportunity. This occurs when it is possible to borrow funds at a lower rate than the rate that can be earned by reinvesting those funds.

Such opportunities present themselves when a portfolio includes securities that are "on special" and the manager can reinvest at a rate higher than the repo rate. For example, suppose that a manager has securities that are "on special" in the portfolio, Bond X, that lenders of funds are willing to take as collateral for two weeks charging a repo rate of say 3%. Suppose further that the manager can invest the funds in a 2-week Treasury bill (the maturity date being the same as the term of the repo) and earn 4%. Assuming that the repo is properly structured so that there is no credit risk, then the manager has locked in a spread of 100 basis points for two weeks. This is a pure arbitrage and the manager faces no risk. Of course, the manager is exposed to the risk that Bond × may decline in value but this the manager is exposed to this risk anyway as long as the manager intends to hold the security.

The results of a study examining the relationship between cash prices and repo rates for bonds that have traded special appeared in the February 1997 and August 1997 market sections of the Bank of England's Quarterly Bulletin. The results of the study suggest a positive correlation between changes in a bond trading expensive to the yield curve and changes in the degree to which it trades special. This result is not surprising. Traders maintain short positions in bonds which have associated funding costs only if the anticipated fall in the bond's is large enough to engender a profit. The causality could run in either direction. For example, suppose a bond is perceived as being expensive relative to the yield curve. This circumstance creates a greater demand for short positions and hence a greater demand for the bonds in the repo market to cover the short positions. Alternatively, suppose a bond goes on special in the repo market for whatever reason. The bond would appreciate in price in the cash market as traders close out their short positions which are now too expensive to maintain. Moreover, traders and investors would try to buy the bond outright since it now would be relatively cheap to finance in the repo market.

The repo market has evolved into one of the largest sectors of the money market because it is used continuously by dealer firms (investment banks and money center banks acting as dealers) to finance positions and cover short positions. The primary borrowers of securities include major security dealers and hedge funds. Conversely, the primary lenders of securities include institutional investors with long investment horizons (e.g., insurance companies, pension funds, mutual funds). These institutional investors view securities lending as an additional source of revenue. Alternatively, viewing the repo market as a mechanism to borrow and lend cash, the primary borrowers of cash are the same institutions that also borrow securities, namely, dealer firms and hedge funds. Lenders of cash include financial institutions, nonfinancial corporations, money market mutual funds, and municipalities.

Another repo market participant is the repo broker. To understand the repo broker's role, suppose that a dealer has shorted $50 million of the current 10-year Treasury note. It will then query its regular customers to determine if it can borrow, via a reverse repo, the 10-year Treasury note it shorted. Suppose that it cannot find a customer willing to do a repo transaction (repo from the customer's perspective, reverse repo from the dealer's perspective). At that point, the dealer will utilize the services of a repo broker who will find the desired collateral and arrange the transaction for a fee.

One important type of repo is a repo/reverse to maturity. A repo/reverse to maturity is one where the term of the repurchase agreement coincides with the maturity date of the collateral and the repurchase price equals the proceeds of the collateral. As before, whether the transaction is a repo or reverse is viewed from the dealer's perspective. This type of transaction is driven primarily for accounting/tax reasons. For example, suppose a dealer has a customer has bond in their portfolio that they would like to sell but the bond is trading below its carrying value. Further suppose the customer does have any gains to offset the loss. In this case, the customer might consider a repo to maturity as an alternative to selling the bond. By doing so, the customer is using the bonds as collateral for a loan and gains access to funds without selling the bond outright.

Another securities lending arrangement that is functionally equivalent to a repurchase agreement is a buy/sell-back agreement. A buy/sell-back agreement separates a securities lending transaction into separate buy and sell trades that are entered into simultaneously. The security borrower buys the security in question and agrees to return the borrowed security (that is, sell back) at some future date for an agreed upon forward price. The forward price is usually derived using a repo rate. A buy/sell-back agreement differs from a repurchase agreement in that the security borrower receives legal title and beneficial ownership of the securities for the length of the agreement. Moreover, the security borrower retains any accrued interest and coupon payments until the security is returned to the lender. Nevertheless, the price on the termination date reflects the fact that the economic benefits of the coupon interest being transferred back to the seller.

Structured repurchase agreements have developed in recent years mainly in the U.S. market where repo is widely accepted as a money market instrument. Following the introduction of new repo types it is also possible now to transact them in other liquid markets.

As the name implies, a London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) financed Treasury repurchase agreement differs from a traditional repo in that the repo rate is tied to three-month LIBOR rather than the overnight Federal funds rates. The repo rate is reset quarterly according to movements in the level of three-month LIBOR. Accordingly, unlike a traditional repo, the repo rate over the term of the agreement is uncertain.

Cross-Currency Repo

A cross-currency repo is an agreement in which the cash lent and securities used as collateral are denominated in different currencies say, borrow U.S. dollars with U.K. gilts used as collateral. Of course, fluctuating foreign exchange rates mean that it is likely that the transaction will need to be marked-to-market frequently in order to ensure that cash or securities remain fully collateralized.

Callable Repo

In a callable repo arrangement, the lender of cash in a term fixed-rate repo has the option to terminate the repo early. In other words, the repo transaction has an embedded interest rate option which benefits the lender of cash if rates rise during the repo's term. If rates rise, the lender may exercise the option to call back the cash and reinvest at a higher rate. For this reason, a callable repo will trade at a lower repo rate than an otherwise similar conventional repo.

Whole Loan Repo

A whole loan repo structure developed in the U.S. market as a response to investor demand for higher yields in a falling interest rate environment. Whole loan repo trades at a higher rate than conventional repo because a lower quality collateral is used in the transaction. There are generally two types: mortgage whole loans and consumer whole loans. Both are unsecuritized loans or interest receivables. The loans can also be credit card payments and other types of consumer loans. Lenders in a whole loan repo are not only exposed to credit risk but prepayment risk as well. This is the risk that the loan package is paid off prior to the maturity date which is often the case with consumer loans. For these reasons, the yield on a whole loan repo is higher than conventional repo collateralized by say U.S. Treasuries, trading at around 20 to 30 basis points over LIBOR.

Total Return Swap

A total return swap structure, also known as a "total rate of return swap," is economically identical to a repo. The main difference between a total return swap and a repo is that the former is governed by the International Swap Dealers Association (ISDA) agreement as opposed to a repo agreement. This difference is largely due to the way the transaction is reflected on the balance sheet in that a total return swap is recorded as an off-balance-sheet transaction. This is one of the main motivations for entering into this type of contract. The transaction works as follows:

The institution sells the security at the market price

The institution executes a swap transaction for a fixed term, exchanging the security's total return for an agreed rate on the relevant cash amount

On the swap's maturity date the institution repurchases the security for the market price

In theory, each leg of the transaction can be executed separately with different counterparties; in practice, the trade is bundled together and so is economically identical to a repo.

Dollar rolls resemble repurchase agreements on a number of dimensions. For example, a dollar roll is a collateralized loan that calls for the sale and repurchase of a pass-through security on different settlement dates. However, unlike a repurchase agreement, the dealer who borrows pass-through securities need only return "substantially identical securities." Although we will discuss this in more detail shortly, for now, "substantially identical securities" returned by the dealer must match certain criteria such as the coupon rate and security type (that is, issuer, e.g., Ginnie Mae) and mortgage collateral (e.g., 30-year fixed rate). These are the same general trade parameters that buyer and seller would agree to when trading pass-throughs on a to-be-announced (TBA) basis. This feature provides valuable flexibility to dealers for either covering short positions or obtaining pass-throughs to collateralize a collateralized mortgage obligation (CMO) deal. In order to obtain this flexibility, the dealer provides the security lender (that is, the investor) provides 100% financing—no overcollateralization or margin required. The financing cost may also be cheaper (sometimes considerably so) because of this flexibility. Lastly, recall that with a repurchase agreement, there is no transfer of security's cash flows. The original owner continues to receive any principal and coupon interest. Not so with a dollar roll, the dealer borrowing the pass-through security keeps the coupon interest and any principal paydown during the length of the agreement.

A mortgage pass-through security (henceforth, pass-through) is created when one or more mortgage holders form a collection (pool) of mortgages and sell shares or participation certificates in the pool. The cash flow of a pass-through depends on the cash flow of the underlying mortgages. It consists of monthly mortgage payments representing interest, the scheduled repayment of principal, and any prepayments.

Payments are made to security holders each month. Neither the amount nor the timing, however, of the cash flow from the mortgage pool is identical to that of the cash flow passed through to investors. The monthly cash flow for a pass-through is less than the monthly cash flow of the underlying mortgages by an amount equal to servicing and other fees. The other fees are those charged by the issuer or guarantor of the pass-through for guaranteeing the issue. The coupon rate on a pass-through is less than the mortgage rate on the underlying pool of mortgage loans by an amount equal to the servicing and guaranteeing fees.

The timing of the cash flows is also different. The monthly mortgage payment is due from each mortgagor on the first day of each month. There is then a delay in passing through the corresponding monthly cash to the security holders, which varies by the type of pass-through. Because of prepayments, the cash flow of a pass-through is not known with certainty.

There are three major types of pass-throughs guaranteed by the following organizations: Government National Mortgage Association ("Ginnie Mae"), Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac. These are called agency pass-throughs. Ginnie Mae pass-throughs are backed primarily by Federal Housing Authority (FHA) insured or Veterans Administration (VA) guaranteed mortgage loans. Correspondingly, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac securitize conforming mortgage loans. Agency pass-throughs are identified by a pool prefix and pool number provided by the agency. The prefix indicates the type of pass-through. The pool number indicates specific mortgages underlying the pass-through as well as the pass-through's issuer.

The trading and settlement of mortgage-backed securities is governed by rules established by the Bond Market Association. We limit our discussion in this section to agency pass-through securities. Many trades of pass-through securities are derived from mortgage pools that have yet to be specified. As a result, no pool information is available at the time of the trade. Such a trade is denoted as a TBA trade (which stands for to be announced). In a TBA trade, the buy and seller agree on the issuer, type of program, coupon rate, face value, the price, and the settlement date. The actual pools underlying the pass-through are not specified. This information is provided by the seller to the buyer before delivery. There are also specified pool trades wherein the actual pool numbers to be delivered are specified.

Agency pass-throughs usually trade on a forward basis and settlement occurs once month. Each pass-through is assigned a settlement day during the month based on the issuer and type of collateral. This system of forward settlement is crucial to the MBS market for two reasons. First, forward settlement allows the originators of mortgages to sell pass-throughs forward before creating mortgage pools. Accordingly, originators can hedge the mortgage rates at which they are lending. Second, forward settlement also facilitates CMO production as the collateral for CMOs is agency pass-throughs. The settlement of CMO deals is usually one month from the pricing date. Thus, issuers of CMOs are active players in the one-month forward market (see Davidson and Ching, 2005). Moreover, it is the demand for newly minted pass-throughs needed for CMO collateral that gives rise to the existence of the dollar roll market.

The process for determining the dollar roll's financing cost is not as straightforward as that of a repurchase agreement. The key elements in determining a dollar roll's financing cost assuming that the dealer is borrowing securities/lending cash are:

The sale price and the repurchase price.

The amount of the coupon payment.

The amount of scheduled principal payments.

The projected prepayments of the security sold to the dealer.

The attributes of the substantially identical security returned by the dealer.

The amount of under- or overdelivery permitted.

Let us consider each of these elements. The repurchase price is usually less than the sale price in a dollar roll. At first blush, this may seem counterintuitive. After all, the repurchase price is always greater than the sale price where the difference represents repo interest. In a dollar roll, the reason the repurchase price is less than the sales price is because of the second element—the investor surrenders any coupon payments they would have received had they simply held the securities during the length of the dollar roll agreement. Thus, the financing costs of a dollar roll depend on the difference between what the investor gives up in terms of forgone coupon interest and what the investor gives back in the form of a lower repurchase price. Specifically, when the yield curve is positively sloped (that is, long-term interest rates exceed short-term interest rates), the coupon rates of newly minted pass-throughs will exceed short-term collateralized borrowing rates. The greater the slope of the yield curve, the lower the repurchase price must be to offset the forgone coupon interest, other things equal.

The third and fourth elements involve principal payments. There are two types of principal payments—scheduled and prepayments. Scheduled principal payments are predictable and are due to loan amortization. Prepayments occur because the homeowner's option to make principal payments in excess of the scheduled amount (in whole or in part) at any time prior to the mortgage's maturity date usually at no cost. As with the coupon payments, the investor forfeits any principal payments during the length of the agreement, A gain will be realized by the dealer on any principal payments if the security is purchased by the dealer at a discount and a loss if purchased at a premium. Because of prepayments, the principal paydown over the life of the agreement is unknown so the investor's borrowing rate is not known with certainty. This uncertainty represents another difference between dollar rolls and repurchase agreements. In a repurchase agreement, the lender of securities/borrower of funds borrows at a known financing rate. Conversely, with a dollar roll, the financing rate is unknown at the outset of the agreement and can only be projected based on an assumed prepayment rate.

The fifth element is another risk since the effective financing cost will depend on the attributes of the substantially identical security that the dealer returns to the lender. Note this differs from a repurchase agreement in that the security borrower must return securities that are identical to those pledged as collateral. A dealer that borrows mortgage pass-throughs will almost never return the identical securities (that is, pass-throughs derived from the same mortgage pools) to the investor. Instead the dealer is only required mortgage pass-throughs that met certain criteria. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, Statement of Position 90-3 requires substantially identical securities met the following criteria:

Be collateralized by similar mortgages.

Be issued by the same agency and be a part of the same program.

Have the same original stated maturity.

Have identical coupon rates.

Be priced at similar market yields.

Satisfy delivery requirements; that is, the aggregate principal amounts of the securities delivered and received back must be within 0.1% of the initial amount delivered.

There are literally hundreds if not thousands of pass-through securities that meet these criteria at any given time. However, these pass-throughs differ in that they are securitized by different mortgage pools. As a result, even among substantially identical securities, some pools perform worse than others.

The last element is the amount of under- or overdelivery permitted. Specifically, the BMA (Bond Market Association) delivery standards permit under- or overdelivery of up to 0.01%. In a dollar roll agreement, both the investor and the dealer have the option to under- or overdeliver: the investor when delivering the securities at the outset of the transaction and the dealer when returning the securities at the end of the agreement.

The decision of whether a mortgage-backed securities investor will participate in a dollar roll agreement depends on a number of factors. These factors include the size of the difference between the sale price and the repurchase price (called the drop or the forward drop), prepayment speeds of the collateral underlying the securities, and available reinvestment rates. In this section, we present two illustrations using discount and premium pass-throughs highlighting how these factors impact the investor's decision to roll their securities.

Dollar Roll with Discount Pass-throughs

Using some information obtained from Bloomberg, consider some Fannie Mae pass-throughs that carry a 5% coupon and a principal balance of $1 million. The payment delay is 54 days and the settlement date is October 12, 2006. Suppose that an investor enters into an agreement with a dealer in which it agrees to sell $1 million par value (that is, unpaid aggregate balance) of these Fannie Mae 5s at 96 13/32 and repurchase substantially identical securities one month later at 96 12/32 (the repurchase price). (In market parlance, a trader would say "buy $1 million of the October/November roll.") Note that the difference in the sales price and the repurchase price is 1/32 and is called the forward drop. The key question that the investor faces is whether she should roll the pass-throughs versus simply holding them over the same time period.

If the investor chooses to roll the pass-throughs, she will receive the sale price of 96 12/32 or $964,062.50 for a $1 million principal balance on the settlement date of October 12, 2006. In addition, the investor will receive 11 days accrued interest of $1,805.56 ($1 million × 5% × (11/360)) because interest starts accruing October 1. The total amount received on the settlement date is $965,590.28. The investor assumes the proceeds of the dollar roll will be reinvested for the length of the agreement from October 12 to November 13 or 32 days. Suppose the relevant reinvestment rate is the rate on a repurchase agreement collateralized by Treasury securities over the same period, which is 5.16%. The reinvestment income generated over the length of the agreement is the repo interest of $4,428.84 (5.16% × $965,590.28 × (32/360)). The investor will have $949,135.71 at the end of the agreement November 13, 2006. This number must be compared to the number of dollars generated by simply holding the pass-through securities over the same period of time.

If the investor holds the pass-throughs, she will receive a cash flow on November 25 for the month of October because of the 54 day stated payment delay. The cash flows consist of coupon interest and principal paydown—both scheduled and prepayments. The interest for the month of October is $4,166.67 (5% × $1 million × 1/12) While the scheduled principal payments are known, prepayments must be forecasted using an assumed prepayment rate which is say 162 PSA. (The prepayment rate, referred to as the prepayment speed, is measured using a standardized benchmark developed by the Bond Market Association (BMA), now the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association (SIFMA). This prepayment rate is referred to as the PSA speed.) The October principal payments are projected to be $3,567.62. The total cash flow to be received by the investor on November 25 is $7,734.29. We must compute the present value of this payment to find how much they will be worth on November 15 (the end of the dollar roll agreement). Using the reinvestment rate of 5.16%, we discount $7,734.29 back 12 days to obtain $7,720.98.

The remaining principal is worth $996,432.38 using the dollar roll repurchase price of 96 12/32. In addition, there will 12 days accrued interest for the month of November of $1,660.72 (5% × $996,432.38 × 12/360) The total number of dollars generated by continuing to hold the pass-through securities on November 13 is $969,693.41. Comparing this number to the future value generated by the dollar roll of $970,019.12 indicates there is a $325.71 gain per $1 million of principal for rolling the pass-throughs.

From the investor's perspective, engaging in a dollar roll is tantamount to financing the pass-throughs using a repurchase agreement. As such, it is possible to compute a breakeven reinvestment rate that would make dollar advantage of rolling the securities equal to zero all else equal. In this example, the breakeven rate is 4.781%. When the investor's reinvestment rate is higher than this, there is an advantage to rolling the pass-throughs all else equal. In comparing financing costs, it is important that the dollar amount of the cost be compared to the amounts borrowed. Moreover, it is not proper to compare financing costs of other alternatives without recognizing the risks associated with a dollar roll.

Dollar Roll with Premium Pass-throughs

Now suppose an investor is contemplating a dollar roll with $1 million Fannie Mae 6% pass-throughs at a price of 100 16/32 for settlement on October 12, 2006. The forward drop is 1/32, and the repurchase price on November 13 (the end of the dollar roll agreement) is 100 15/32. Using an assumed prepayment assumption of 309 PSA, the breakeven reinvestment rate is 5.386%. If the investor uses the one-month repo rate as a proxy for their reinvestment rate of 5.16%, the investor would not want to roll the pass-throughs. Specifically, using these assumptions, there is a $202.02 (per $1 million) advantage for holding rather than rolling these premium pass-throughs.

Because of the unusual nature of the dollar roll transaction as a collateralized borrowing vehicle, it is only possible to estimate the financing cost (that is, the breakeven reinvestment rate). The reason being that the speed of prepayments will affect the financing rate the investor pays by rolling the pass-throughs. In our illustration, since the pass-throughs are trading at a discount, faster prepayments will benefit whoever holds the securities. Thus, the investor's financing rate obtained via a dollar roll will be directly related to the prepayment speed. An investor can perform a sensitivity analysis to determine the effect of varying prepayment speeds on the financing rate. If the pass-throughs are trading at a premium, the investor's financing rate will be inversely related to the prepayment speed.

In addition to the uncertainty about the prepayment speed, there is another risk that involves the substantially identical securities returned by the dealer at the end of the dollar roll. As noted earlier, even among substantially identical securities, some pools perform worse than others. The risk is that the dealer will deliver securities from pools that perform poorly.

A repurchase agreement is the sale of a security with a commitment by the seller to buy the same security back from the purchaser at a specified price at a designated future date. They serve a means to finance bond positions and borrow securities. The liquidity of a bond market is enhanced by an active repo market. In this chapter, we discussed the mechanics of a repurchase agreement and the determinants of repo interest rates. We described a buy/sell-back agreement as well as a structured repo agreement, which is becoming more widely traded. We also discuss a specialized reverse repurchase with pass-through securities serving as collateral known as a dollar roll. After briefly reviewing some background information about pass-through securities and their trading/settlement process, we detailed the mechanics of dollar roll agreements with particular attention to the determination of the financing costs. Finally, the risks in a dollar roll from the investor's perspective were examined.

Comotto, R. (2005). The European repo market. In F. J. Fabozzi and S. V. Mann (eds.), Securities Finance: Securities Lending and Repurchase Agreements (pp. 234-240). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Davidson, A., and Ching, A. (2005). Agency mortgage-backed securities. In F. J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Fixed-Income Securities, 7th edition (pp. 513-540). New York: McGraw Hill.

Fabozzi, F. J., and Mann, S. V. (2005a). Repurchase and reverse repurchase agreements. In F. J. Fabozzi and S. V. Mann (eds.), Securities Finance: Securities Lending and Repurchase Agreements (pp. 221-240). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fabozzi, F. J. and Mann, S. V. (2005b). Dollar rolls. In F. J. Fabozzi and S. V. Mann (eds.), Securities Finance: Securities Lending and Repurchase Agreements (pp. 283-298). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Fleming, M. J. (2000). The benchmark U.S. Treasury market: Recent performance and possible alternatives. FRBNY Economic Policy Review, April: 129-145.