FRANK J. JONES, PhD

Professor, Accounting and Finance Department, San Jose State University and Chairman of the Investment Committee, Salient Wealth Management, LLC

FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

Abstract: At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the world's stock exchanges were a complex of separate, independent, single-product exchanges. During the first part of this century, however, these exchanges have become interconnected within and across country lines and have become multiproduct exchanges. That is, some of the world's stock exchanges have become international, multiproduct exchanges. The exchanges have and will continue to change rapidly, both diversifying and integrating. In addition to the sanctioned stock exchanges, the off-exchange markets have become much more important in their size and diversity. The U.S. stock market has become a complex of interconnected exchanges and off-exchange markets.

Keywords: market structure, order driven, quote-driven, market orders, limit orders, bid quote, offer quote, pure order-driven market, natural buyers, natural sellers, continuous market, call auction, brokers, agents, dealers, market makers, principals, specialist, national best bid and offer (NBBO), hybrid markets, system orders, floor brokers, commission broker, limit order book, competitive-dealer quote-based system, off-exchange markets, alternative electronic markets, electronic communications networks (ECNs), alternative trading systems, cross networks, dark pools, fragmentation, alternative display facility (ADF), tick size, block, block trade

This chapter offers a snapshot of the current but evolving U.S. stock markets. International exchanges are considered herein only in their relationship to the U.S. stock markets. There are two fundamental differences among U.S. and international exchanges. The first is their method of trading, that is, their market structure. The market structures of U.S. and international exchanges have evolved and even changed radically. One cannot appreciate current exchanges without understanding their market structure. In addition, the nature of the exchanges' business organizations have changed considerably, from membership floor–traded organizations to publicly owned electronic trading organizations. This chapter begins with discussions of the market structures and business organizations of the U.S. exchanges. (For a more detailed discussion of some of the topics covered in this chapter, see Schwartz and Francioni [2004].)

An exchange is often defined as a market where intermediaries meet to deliver and execute customer orders. This description, however, also applies to many dealer networks. In the United States, an exchange is an institution that performs this function and is registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as an exchange. There are also some off-exchange markets that perform this function.

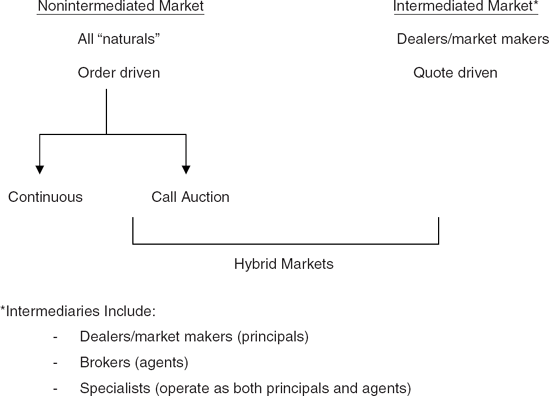

There are two overall market models for trading stocks. The first model is order driven, in which buy and sell orders of public participants who are the holders of the securities establish the prices at which other public participants can trade. These orders can be either market orders or limit orders. The second model is quote-driven, in which intermediaries, that is market-makers or dealers, quote the prices at which the public participants trade. Market makers provide a bid quote (to buy) and an offer quote (to sell) and realize revenues from the spread between these two quotes. Thus, market makers derive a profit from the spread and the turnover of their stocks.

Participants in a pure order-driven market are referred to as "naturals" (the natural buyers and sellers). No intermediary participates as a trader in a pure order-driven market. Rather, the investors supply the liquidity themselves. That is, the natural buyers are the source of liquidity for the natural sellers, and vice versa. The naturals can be either buyers or sellers, each using market or limit orders.

Order-driven markets can be structured in two very different ways: a continuous market and a call auction at a specific point of time. In the continuous market, a trade can be made at any moment in continuous time during which a buy order and a sell order meet at a specific time. In this case, trading is a series of bilateral matches. In the call auction, orders are batched together for a simultaneous execution in a multilateral trade at a specific point in time. At the time of the call, a market-clearing price is determined; buy orders at this price and higher and sell orders at this price and lower are executed.

Continuous trading is better for customers who need immediacy. However, for markets with very low trading volume, an intraday call may focus liquidity at one (or a few) times of the day and permit the trades to occur. In addition, very large orders—block trades that will be described later—may be advantaged by the feasibility of continuous trading.

Nonintermediated markets involve only naturals; that is, such markets do not require a third party. A market may not, however, have sufficient liquidity to function without the participation of intermediaries, who are third parties in addition to the natural buyers and sellers. This leads to the need for intermediaries and quote-driven markets.

Quote-driven markets permit intermediaries to provide liquidity. Intermediaries may be brokers (who are agents for the naturals); dealers or market makers (who are principals in the trade); or specialists, as on the New York Stock Exchange (who act as both agents and principals). Dealers are independent, profit-making participants in the process.

Dealers operate as principals, not agents. Dealers continually provide bid and offer quotes to buy for or sell from their own accounts and profit from the spread between their bid and offer quotes.

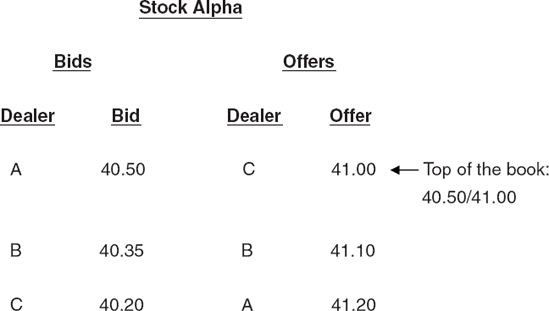

Dealers compete with each other in their bids and offers. Obviously, from the customer's perspective, the "best" market is highest bid and lowest offer among the dealers. This highest bid/lowest offer combination is referred to as the "inside market" or the "top of the book." For example, assume that dealers A, B, and C have the bids and offers (also called asking prices) for stock Alpha as shown in Figure 11.1.

The best (highest) bid is by dealer A of 40.50; the best (lowest) offer is by dealer C of 41.00. Thus, the inside market is 40.50 bid (by A) and 41.00 offer (by C). Note that A's spread is 40.50 bid and 41.20 offer for a spread (or profit margin) of 0.70. A has the highest bid but not the lowest offer. C has the lowest offer but not the highest bid. B has neither the highest bid nor the lowest offer.

For a stock in the U.S. market, the highest bid and lowest offer across all markets is called the national best bid and offer (NBBO).

Dealers provide value to the transaction process by providing capital for trading and facilitating order handling. With respect to providing capital for trading, they buy and sell for their own accounts at their bid and offer prices, respectively, thereby providing liquidity. With respect to order handling, they provide value in two ways. First, they assist in the price improvement of customer orders, that is, the order is executed within the bid/offer spread. Second, they facilitate the market timing of customer orders to achieve price discovery. Price discovery is a dynamic process that involves customer orders being translated into trades and transaction prices. Because price discovery is not instantaneous, individual participants have an incentive to "market-time" the placement of their orders. Intermediaries may understand the order flow and may assist the customer in this regard. The intermediary may be a person or an electronic system.

The over-the-counter (OTC) markets are quote-driven markets. The OTC markets began during a time when stocks were bought and sold in banks and the physical certificates were passed over the counter.

A customer may choose to buy or sell to a specific market maker to whom they wish to direct an order. Directing an order to a specific market is referred to as "preferencing."

Overall, nonintermediated, order-driven markets may be less costly due to the absence of profit-seeking dealers. But the markets for many stocks are not inherently sufficiently liquid to operate in this way. For this reason, intermediated, dealer markets are often necessary for inherently less liquid markets. The dealers provide dealer capital, participate in price discovery and facilitate market timing, as discussed above.

Because of the different advantages of these two approaches, many equity markets are now hybrid markets. For example, the NYSE is primarily a continuous auction order-driven system based on customer orders but the specialists enhance the liquidity by their market making to maintain a fair and orderly market. Overall, the NYSE is primarily an auction, order-driven market which has specialists (who often engage in market making), other floor traders, call markets at the open and close, and upstairs dealers who provide proprietary capital to facilitate block transactions. Thus, the NYSE is a hybrid combination of these two models. Another hybrid aspect of the NYSE is that it opens and closes trading with a call auction. The continuous market and call auction market are combined. Thus, the NYSE is a continuous market during the trading day and a call auction market to open and close the market and to reopen after a stop in trading. Thus, the NYSE is a hybrid market.

Nasdaq began as a descendent of the OTC dealer network, and is a dealer quote-driven market. It remains primarily a quote-driven market, but has added some order-driven aspects such as its limit order book, called SuperMontage (discussed below), which made it a hybrid market.

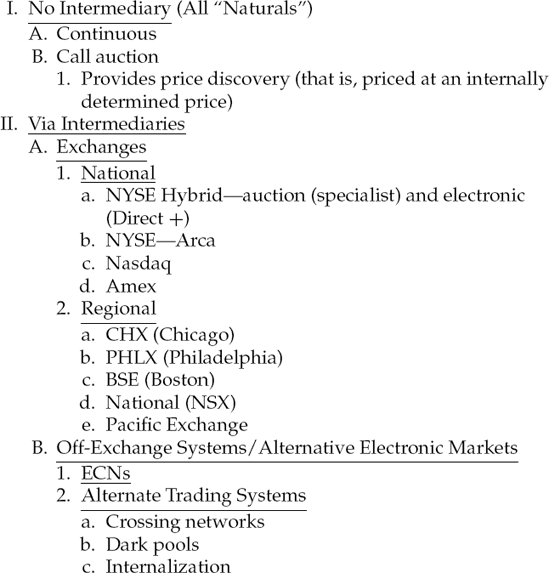

An overview of the nonintermediated, auction, order-driven market and the intermediated, dealer, quote driven markets is provided in Figure 11.2.

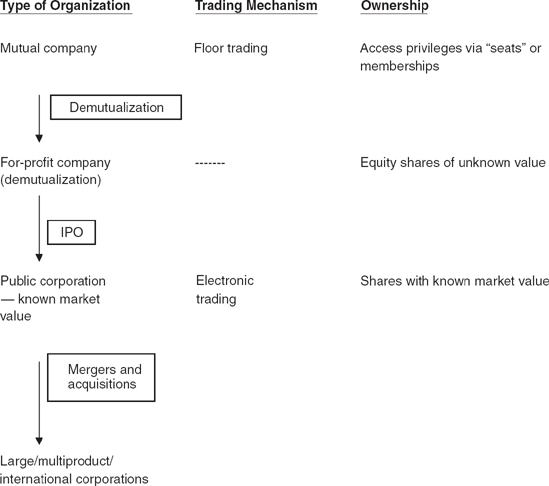

Another structural change that has occurred in exchanges is their evolution from membership-owned, floor-traded, organizations to publicly owned electronically traded (that is, no trading floor) organizations. The nature of this evolution (or revolution) is discussed in the next section.

Exchanges have traditionally been organizations built around a physical trading floor.

They have also usually been mutual organizations that are owned and operated on a nonprofitbasis for the benefit of their members, those who operate on the trading floor. The ownership by the members is reflected in the memberships or "seats," which provide floor access or trading privileges as well as ownership rights. As the profits derived from these trading privileges increase, the prices of the seats increase and the value of the members' equity in their exchange increases. Thus, a membership organization's goal is to increase the value of the access privileges, which increases the price of a seat. A mutual organization's primary objective, thus, is to increase the income of the individual members not the profit of overall organization, which is a nonprofit organization.

However, membership organizations may not find it beneficial to themselves to adopt some changes which are beneficial to the customers of the exchange, the buyers and sellers of the exchange's products, because such changes may not be beneficial to the owners of the exchange, the members. For example, adopting a new technology may benefit the customers by reducing the transaction costs but also decrease the value of access privileges and seats of a membership organization. Thus, the members/owners in a membership organization often resist technological innovations which could benefit customers but reduce the value of their own trading income.

In contrast, a publicly owned equity-based organization is a corporation and operated for a profit. And the profit of the overall organization accrues to its shareholders via an increase in the value of its equity shares. Thus, an equity-based organization might adopt the above-mentioned technology if it benefited its customers, increased its profits, and increased its stock price. The equity-based organization is free of the conflicts of a member organization between trader income and organizational profits.

While an equity-based organization may be superior over time in serving its customers, the difficult issue is convincing the members/owners in a mutual organization to agree to a demutualization and public ownership. The demutualization occurs by giving the members shares or equity in the demutualized organization in exchange for their seats in the mutual organization. Thus, the members would receive wealth/equity shares in exchange for income/access privileges. For such reasons, many exchanges have converted from membership organizations to publicly owned equity-based demutualized organizations in recent years.

Such a demutualization will align the interests of the customers of the organization and the owners of the organization. After the demutualization from a mutual company to a stock company, however, one more step is necessary before equity capital can be raised for the exchange and alliances among exchanges can be easily made with stock. Immediately after the demutualization, the stock of the equity company may be privately held and the equity shares do not have a known market value. Knowing this value is necessary if the shares are going to be exchanged, new equity capital is raised, or mergers or acquisitions among such organizations are to be consummated. In order to give the stock a known market value, the newly equity-based organization has to "go public," that is, sell at least some its stock on the public markets via an initial public offering (IPO) and then list its shares on a secondary stock market, such as the NYSE or Nasdaq. Once the IPO is complete, the resulting "corporation" knows its overall value ("market value," "market capitalization," or simply "market cap"), which is its share price multiplied by its number of shares. Corporations can then use their stock to acquire other corporations with their shares. Corporations can also use the value of their corporation as a basis for being acquired by another firm via its stock or cash. Equity or for-profit organizations have the flexibility to raise capital, make acquisitions, and acquire other organizations without resistance from its members, who would be considering their own income.

Overall, before demutualization, the market participants and market owners are the same via memberships, seats or access privileges. This is ideal for a trading floor organization. The members derive their income from trading on the floor. As a result, floor trading organizations tend to be mutual organizations. After demutualization, the market participants and the market owners are not necessarily the same entities and, thus, may have different objectives, the traders motivated by trading income and the shareholders motivated by organizational (that is, corporate) profits. Thus, after the demutualization and the subsequent IPO, a common change is that the corporation can take actions which benefit the corporation itself by providing better service to its customers, even though trader profits may be disadvantaged. The degree of electronic trading increases and trading may become exclusively electronic or remain a mix of floor trading and electronic, often called a hybrid. The owners are shareholders, and they do not derive their income from trading on the floor. This sequence of actions is shown in Figure 11.3.

Traditionally, exchanges of most types have been based on floor trading, and the ownership of the exchanges has been with the floor traders, both individuals and firms. Changes in exchange structure and ownership began in the 1980s. Most notable were the changes that related to the "Big Bang" in London during 1986. These reforms related to the London Stock Exchange (LSE) included the abolition of minimum commissions and the introduction of "dual capacity," whereby member firms could be both brokers (agents) and "jobbers" (the British term for dealers who are principals in a transaction). One outcome of these and other changes was that the LSE's trading floor was closed and replaced by "screen trading," which is a dealer OTC market. The LSE became a public company in July, 2001 (ticker symbol: LSE).

Since then, the major futures exchanges, including the Chicago Mercantile Exchange and the Chicago Board of Trade, have become electronic trading corporations and have merged. The International Securities Exchange, an electronic options exchange, began (in 2000) as a membership-owned exchange, subsequently demutual-ized, and then subsequently did an IPO (in 2005). The NYSE became a publicly owned mainly electronically traded stock exchange. There were other such transformations.

The view of the U.S. stock market "from 30,000 feet" is that of a large homogeneous market. But while it has been large, it has not been homogeneous since the 1970s. It has become even much more heterogeneous since the 1990s. The U.S. stock market is now composed of the stock exchanges and OTC markets and also, more recently, the off-exchange markets. This section provides the "big picture" of the current stock market—specific parts of the market are examined more closely in subsequent sections.

The U.S. stock market began over two centuries ago and has evolved considerably since then. The U.S. stock market has traditionally been the core of the world capital markets. Over the last few decades, there have been significant changes in the U.S. stock market and also the other international stock markets. But, undoubtedly, during the 1990s the pace and extent of this change has accelerated.

The stock exchanges have been the primary component of the U.S. stock market. Among the types of changes in the U.S. stock exchanges are:

The market structures of the exchanges.

The trading mechanisms of the exchanges.

Consolidation among different types of assets, for example, securities options and futures.

Growth and diversity of the off-exchange markets.

Consolidation internationally.

While the exchanges have been the main component of the U.S. stock market, the OTC markets and the off-exchange markets have also become important parts of the U.S. stock market. The off-exchange markets have also grown and become much more diverse since 2005.

This section covers the exchanges and the OTC markets; the next section considers the off-exchange markets. Given the pace and extent of the recent changes, there is a high likelihood that the markets will be much different during the next decade than it is now.

The international stock exchanges have also changed and, in fact, in some cases, have become integrated with the U.S. exchanges. However, the international stock markets are not considered here except for their relationship with U.S. exchanges.

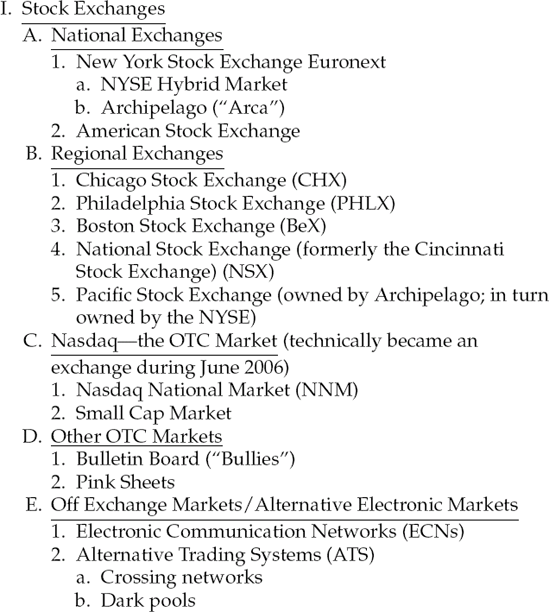

Figure 11.4 provides a general overview, or the "big picture," of the current construct of the U.S. stock markets. The components of the current U.S. stock market are discussed individually in the following sections. This section treats the components of the U.S. stock market, including the national exchanges, the NYSE and the American Stock Exchange (Amex); the regional stock exchanges; Nasdaq, technically an OTC market, not an exchange (until June 2006); other OTC markets; and other stock exchange markets.

As of the first quarter of 2008, the U.S. stock markets are dominated by the NYSE and Nasdaq, the two largest exchanges (as discussed below, until June 2006 Nasdaq was not technically an exchange).

New York Stock Exchange

The beginning of the NYSE is identified as May 17, 1792, when the Buttonwood Agreement was signed by 24 brokers outside of 68 Wall Street in New York under a button-wood tree. The current NYSE building opened at 18 Broad Street on April 22,1903 (the "main room"). In 1922, a new trading floor (the "garage") was opened at 11 Broad Street.

Additional trading floor space was opened in 1969 and in 1988 (the "blue room"). Finally, another trading floor was opened at 30 Broad Street in 2000. Notably, for reasons discussed below, during early 2006, the NYSE closed the trading room at 30 Broad Street with the beginning of the NYSE Hybrid Market and a greater proportion of the trading being executed electronically. The NYSE is referred to as the "Big Board."

The NYSE trading mechanism has been based on the specialist system. This system, as discussed above, is a hybrid of primarily an order-driven market with some quote-driven features. According to this mechanism, each stock is assigned to an individual specialists. Each specialist "specializes" in many stocks but each stock is assigned to only one specialist. Each specialist is located at a "booth" or "post." All orders for a stock are received at this post, and the specialist conducts an auction based on these orders to determine the execution price. The orders arrive at the specialists' posts either physically, delivered via firm brokers, or electronically via the Designated Order Turnaround (DOT) system or its successors. In conducting the auction, typically the specialist is an agent, simply matching orders. At times, however, the specialist becomes a principal and trades for itself in the interest of maintaining an "orderly market."

Limit orders, as opposed to market orders, are kept by the specialist in their "book," originally a physical paper book but now an electronic book. These limit orders are executed by the specialist when the market price moves to the limit. At one time, the book could be seen only by the specialist, which was judged to be a significant advantage for the specialist, but now the book is open to all the traders on the exchange floor. Overall, the NYSE trading mechanism is an auction-based, order-driven market.

This type of mechanism is often judged to provide the best price but, on a time basis, often a less rapid execution. There is, thus, a trade-off between price and speed.

The need for "space" for trading floors for the NYSE derives from its trading mechanism, a floor-based specialist system. The amount of space necessary depends not only on overall trading volume, but also the fraction of this volume that is handled by the specialist.

The NYSE lists stocks throughout the United States (as well as some international stocks) and, thus, is a "national exchange."

Trading Mechanism—The Specialist System Fundamentally, the NYSE is an auction-type market based on orders (order driven). As indicated above, the traditional trading mechanism for the NYSE is the specialist system. However, the volume of trading that has occurred electronically has increased continually. In 2006, with the advent of NYSE Hybrid Market, the degree of electronic trading has increased significantly, as discussed below.

Here, we discuss the traditional NYSE specialist system in more detail. Trading in stocks listed on the NYSE is conducted as a centralized continuous auction market at a designated physical location on the trading floor, called a post, with brokers representing their customers' buy and sell orders. A single specialist is the market maker for each stock. A member firm may be designated as a specialist for the common stock of more than one company; that is, several stocks can trade at the same post. But only one specialist is designated for the common stock of each listed company.

The NYSE began its DOT (Designated Order Turnaround) system during 1976. This system, now called SuperDOT, is an electronic order routing and reporting system that links member firms worldwide electronically directly to the specialist's post on the trading floor of the NYSE.

The NYSE SuperDOT system routes NYSE listed stock orders electronically directly to a specialist on the exchange trading floor, rather than through a broker. The specialist then executes the orders. This system was initially introduced as the DOT system but is now referred to as the SuperDOT system. The SuperDOT system is used for small market orders, limit orders, and basket (or portfolio) trades and program trades.

The SuperDOT system can be used for under 100,000 shares with priority given to orders of 2,100 shares or less. After the order has been executed, the report of the transaction is sent back through the SuperDOT system.

According to the NYSE, as of 2007, over 99% of the orders executed through the NYSE were done through SuperDOT, which meets the continually increasing demand, which stood at 20 million quotes, 50 million orders, and 10 million reports daily.

In addition to the single specialist market maker on the exchange, other firms that are members of an exchange can trade for themselves or on behalf of their customers. NYSE member firms, which are broker-dealer organizations that serve the investing public, are represented on the trading floor by brokers who serve as fiduciaries in the execution of customer orders.

The largest membership category on the NYSE is that of the commission broker. A commission broker is an employee of one of the securities houses (stockbrokers or wire houses) devoted to handling business on the exchange. Commission brokers execute orders for their firm on behalf of their customers at agreed commission rates. These houses may deal for their own account as well as on behalf of their clients.

Other transactors on the exchange floor include the following categories. Independent floor brokers (nicknamed "$2 brokers") work on the exchange floor and execute orders for other exchange members who have more orders than they can handle alone or who require assistance in carrying out large orders. Floor brokers take a share in the commission received by the firm they are assisting. Another category, registered traders, are individual members who buy and sell for their own account. Alternatively, they may be trustees who maintain memberships for the convenience of dealing and to save fees.

The major type of exchange participant is the specialist.

NYSE Specialist As indicated, specialists are dealers or market makers assigned by the NYSE to conduct the auction process and maintain an orderly market in one or more designated stocks. Specialists may act as both a broker (agent) and a dealer (principal). In their role as a broker or agent, specialists represent customer orders in their assigned stocks, which arrive at their post electronically or are entrusted to them by a floor broker to be executed if and when a stock reaches a price specified by a customer (limit or stop order). As a dealer or principal, specialists buy and sell shares in their assigned stocks for their own account as necessary to maintain an "orderly market." Specialists must always give precedence to public orders over trading for their own account.

In general, public orders for stocks traded on the NYSE, if they are not sent to the specialist's post via SuperDOT, are sent from the member firm's office to its representative on the exchange floor, who attempts to execute the order in the trading crowd. There are certain types of orders where the order will not be executed immediately on the trading floors. These are limit orders and stop orders. If the order is at a limit order or a stop order and the member firm's floor broker cannot transact the order immediately, the floor broker can wait in the trading crowd or give the order to the specialist in the stock, who will enter the order in that specialist's limit order book (or simply, the book) for later execution based on the relationship between the market price and the price specified in the limit or stop order. The book is the list on which specialists keep the limit and stop orders that are given to them, arranged with size, from near the current market price to farther away from it. Whereas the book used to be an actual physical paper book, it is now electronic. While for many years only the specialist could see the orders in the limit order book, with the NYSE's introduction of OpenBook in January 2002, the book was electronically made available to the traders on the exchange floor.

A significant advantage of the NYSE market is its diversity of participants. At the exchange, public orders meet each other often with minimal dealer intervention, contributing to an efficient mechanism for achieving fair securities prices. The liquidity provided in the NYSE market stems from the active involvement of the following principal groups: the individual investor; the institutional investor; the member firm acting as both agent and dealer; the member-firm broker on the trading floor acting as agent, representing the firm's customer orders; the independent broker on the trading floor acting as agent and handling customer orders on behalf of other member firms; and the specialist, with assigned responsibility in individual securities on the trading floor. Together, these groups provide depth and diversity to the market.

NYSE-assigned specialists have four major roles:

As agents, they execute market orders entrusted to them by brokers, as well as orders awaiting a specific market price.

As catalysts, they help to bring buyers and sellers together.

As dealers, they trade for their own accounts when there is a temporary absence of public buyers or sellers, and only after the public orders in their possession have been satisfied at a specified price.

As auctioneers, they quote current bid-ask prices that reflect total supply and demand for each of the stocks assigned to them.

In carrying out their duties, specialists may, as indicated, act as either agents or principals. When acting as an agent, the specialist simply fills customer market orders or limit or stop orders (either new orders or orders from their book) by opposite orders (buy or sell). While acting as a principal, the specialist is charged with the responsibility of maintaining a "fair and orderly market." Specialists are prohibited from engaging in transactions in securities in which they are registered unless such transactions are necessary to maintain a fair and orderly market. Specialists profit only from those trades in which they are involved; that is, they realize no revenue for trades in which they are an agent.

The term "fair and orderly market" means a market in which there is price continuity and reasonable depth. Thus, specialists are required to maintain a reasonable spread between bids and offers and small changes in price between transactions. Specialists are expected to bid and offer for their own account if necessary to promote such a fair and orderly market. They cannot put their own interests ahead of public orders and are obliged to trade on their own accounts against the market trend to help maintain liquidity and continuity as the price of a stock goes up or down. They may purchase stock for their investment account only if such purchases are necessary to create a fair and orderly market.

Specialists are also responsible for balancing buy and sell orders at the opening of the trading day in order to arrange an equitable opening price for the stock. Specialists are expected to participate in the opening of the market only to the extent necessary to balance supply and demand for the security to affect a reasonable opening price. While trading throughout the day is via a continuous auction-based system, the opening is conducted via a single-priced call auction system. The specialists conduct the call and determine the single price.

If there is an imbalance between buy and sell orders either at the opening of or during the trading day and the specialists cannot maintain a fair and orderly market, then they may, under restricted conditions, close the market in that stock (that is, discontinue trading) until they are able to determine a price at which there is a balance of buy and sell orders. Such closes of trading can occur either during the trading day or at the opening, which is more common, and can last for minutes or days. Closings of a day or more may occur when, for example, there is an acquisition of one corporation by another or when there is an extreme announcement by the corporation. For this reason, many announcements are made after the close of trading.

NYSE trading officials oversee the activities of the specialists and trading-floor brokers. Approval from these officials must be sought for a delay in trading at the opening or to halt trading during the trading day when unusual trading situations or price disparities develop.

Because of their critical public role and the necessity of capital in performing their function as a market-maker, capital requirements are imposed by the exchanges for specialists.

American Stock Exchange

The American Stock Exchange (Amex) dates from colonial times when brokers conducted outdoor markets to trade new government securities. Amex began trading at the curbstone on Broad Street near Exchange Place. Until 1929, it was called the New York Curb Exchange. In 1921, the Amex moved inside into the building where it still resides at 86 Trinity Place in New York City. In 1998, Amex merged with the National Association of Securities Dealers (NASD), which then operated Nasdaq, to create the Nasdaq-Amex Market Group wherein Amex was an independent member of the NASD parent. After conflicts between the NASD and Amex members, the Amex members bought Amex from NASD and acquired control in 2004. Amex continued to be owned by its members until its acquisition by the NYSE in early 2008.

Amex, like the NYSE, lists stocks from throughout the United States and also international stocks. Amex is therefore a national exchange. Amex is also an auction-type market based on orders. Its specialist system is similar to that of the NYSE.

Amex developed exchange-traded funds (ETFs). The first ETF, the SPY ETF, based on the S&P 500 index, was listed on the Amex on January 29, 1993. Although ETFs have proved to be a very successful product and most of the listings remain on the Amex, most of the trading volume has migrated to other exchanges, including the NYSE and Nasdaq.

The number of listings on and the trading volume of stocks on the Amex have continued to decline in recent years, and as of early 2008, the Amex is regarded as a minor market in U.S. stocks, although it continues to trade some small to mid-sized stocks.

Amex is the now highly dependent on trading in stock options.

Regional Exchanges

Regional exchanges developed to trade stocks of local firms that listed their shares on the regional exchanges and also to provide alternatives to the national stock exchanges for their listed stocks. Regional stock exchanges now exist in Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston and have existed in many other U.S. cities. These exchanges have also been specialist-type, auction-based systems. Some of the regional stock exchanges, including Philadelphia and Boston, as well as the Amex, have been driven by trading in stock options and index options rather than stock in recent years.

Chicago Stock Exchange The Chicago Stock Exchange (CHX) was founded on March 21, 1882. In 1949, it merged with the St. Louis, Cleveland, and Minneapolis/St. Paul Stock Exchanges and changed its name to the Midwest Stock Exchange. In 1993, it changed its name back to the Chicago Stock Exchange and is the most active regional exchange.

Philadelphia Stock Exchange The Philadelphia Stock Exchange (PHLX) is the oldest stock exchange in the United States, founded in 1790. In 2005, a number of large financial firms purchased stakes in the PHLX as a hedge against growing consolidation of stock trading by the NYSE and Nasdaq. These firms—Morgan Stanley, Citigroup, Credit Suisse First Boston, UBS AG, Merrill Lynch, and Citadel Investment Group—collectively own about 45% of the PHLX.

During October 2007, PHLX announced that it was for sale by a group of its shareholders. On November 7, 2007 Nasdaq announced a "definitive agreement" to purchase PHLX for $652 million, with the transaction expected to close in early 2008.

The Philadelphia Stock Exchange handles trades for approximately 2,000 stocks, 1,700 equity options, 25 index options, and a number of currency options. As of 2007, it had a 14% U.S. market share in exchange-listed stock options trading.

Boston Stock Exchange The Boston Stock Exchange (BSE) was founded in 1834, the third-oldest stock exchange in the United States. The Boston Options Exchange (BCX), a facility of the BSE, is a fully automated options market. On October 2, 2007, Nasdaq agreed to acquire BSE for $61 million.

National Stock Exchange The National Stock Exchange (NSX), now in Chicago, was founded in 1885 in Cincinnati, Ohio as the Cincinnati Stock Exchange. In 1976, it closed its physical trading floor and became the first all-electronic stock market in the United States. The Cincinnati Stock Exchange moved its headquarters to Chicago in 1995 and changed its name to the National Stock Exchange during November 2003. The NSX handles a significant share, approximately 20%, of all Nasdaq-listed securities.

Pacific Exchange The Pacific Exchange began in 1957 when the San Francisco Stock and Bond Exchange (founded in 1882 with a trading floor in San Francisco) and the Los Angeles Oil Exchange (founded in 1889 with a trading floor in Los Angeles) merged to form the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange (the trading floors were kept in both places). The name was changed to the Pacific Stock Exchange in 1973, and options trading began in 1976. In 1997, its name was changed to the Pacific Exchange. In 1999, the Pacific Exchange (PCX) was the first U.S. stock exchange to demutualize. In 2001, the Los Angeles trading floor was closed and the next year the San Francisco trading floor was closed (the options trading floor still operates in San Francisco.)

On September 27, 2005, the Pacific Exchange was bought by the ECN Archipelago, which was in turn bought by the NYSE in 2006. No business is conducted under the name Pacific Exchange, thus ending its separate identity. All formerly PCX stock and options trading takes place through NYSE Arca.

Overall, as indicated by these brief descriptions of regional exchanges, some of the regional exchanges have diversified into options trading to remain viable. Some have made the transformation from membership-owned, trading floor organizations to publicly owned electronic organizations, and others have remained in their original forms. Finally, the regional exchanges have become attractive acquisition targets for larger exchanges, with some having already been acquired and others remaining potential merger targets.

A significant change in the U.S. stock market occurred during 1971 when the National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations System, now often referred to as NASDAQ (or Nasdaq, as referred to in this chapter), was founded. When it began trading on February 8, 1971, Nasdaq was the world's first electronic stock market. Nasdaq was founded by the NASD. Fundamentally, Nasdaq is a dealer-type system based on quotes (quote driven).

The NASD divested itself of Nasdaq in a series of sales in 2000 and 2001 to form a publicly traded company, the Nasdaq Stock Market, Inc. The Nasdaq Stock Market is a public corporation, the stock of which was listed on its own stock exchange at its IPO on July 1, 2002 (ticker: NDAQ).

Initially, the Nasdaq was simply a computer bulletin board system that did not connect buyers and sellers. The Nasdaq helped lower the spread (the difference between the bid price and the ask price of the stock) and so was unpopular among brokerage firms because they profited on the spread. Since then, the Nasdaq has become more of a stock market, adding automated trading systems and trade and volume reporting.

The Nasdaq, as an electronic exchange, has no physical trading floor, but makes all its trades through a computer and telecommunications system. Since there is no trading floor where the Nasdaq operates, the stock exchange built a site in New York City's Times Square to create a physical presence. The exchange is a dealers' market, meaning brokers buy and sell stocks through a market maker rather than from each other. A market maker deals in a particular stock and holds a certain number of stocks on its own books so that when a broker wants to purchase shares, the broker can purchase them directly from the market maker.

Nasdaq is a dealer system or OTC system where multiple dealers provide quotes (bids and offers) and make trades. There is no specialist system, and therefore there is no single place where an auction takes place. Nasdaq is essentially a telecommunication network that links thousands of geographically dispersed, market-making participants. Nasdaq is an electronic quotation system that provides price quotations to market participants on Nasdaq listed stocks. Nasdaq is essentially an electronic communications network (ECN) structure that allows multiple market participants to trade through it, increasing competition, as discussed below.

Since Nasdaq dealers provide their quotes independently, the market has been called "fragmented." So while the NYSE market is an auction/agency, order-based market, the Nasdaq is a competitive dealer quote-based system.

Until 1987, most trading occurred via telephone. During the October 9, 1987, crash, however, dealers did not respond to telephone calls. As a result, the Nasdaq developed the Small Order Execution System (SOES), which provides an electronic method for dealers to enter their trades. The Nasdaq requires that the market makers honor their trades over the SOES. The purpose of the SOES is to ensure that during turbulent market conditions small market orders are not forgotten but are automatically processed.

Over the years, the Nasdaq became more of a stock market by adding trade and volume reporting and automated trading systems. In October 2002, the Nasdaq started a system, called SuperMontage, which has led to a change in the Nasdaq from a quote-driven market to a market that provides both quote-driven and order-driven aspects; that is, it has become a hybrid market. This system permits dealers to enter quotes and orders at multiple prices and then displays these aggregate submissions at five different prices on both the bid and offer sides of the market. Su-perMontage also provides full anonymity, permits dealers to specify a reserve size (that is, they do not have to display their full order), offers price and time priority, allows market makers to internalize orders, and includes pref-erenced orders. In effect, SuperMontage is the Nasdaq's order display and execution system.

The advent of SuperMontage continues completing Nasdaq's transformation from a quote-driven market to a hybrid market that contains both quote- and order-driven features. The Nasdaq added a third component to the hybrid, which is a call auction that both opens and closes the market. Currently, SuperMontage competes with the alternative display facility (ADF) that is operated by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). Super-Montage is a key feature in Nasdaq's development.

There are two sections of the Nasdaq stock market: the Nasdaq National Market (NNM) and the Small Cap Market (also known as the Nasdaq Capital Market Issues). For a stock to be listed on the NNM, the company must meet certain strict financial criteria. For example, a company must maintain a stock price of at least $1, and the total value of outstanding stocks must be at least $1.1 million and must meet lower requirements for assets and capital.

To qualify for listing on the exchange, a company must be registered with the SEC and have at least three market makers. However, the Nasdaq also has a market for smaller companies unable to meet these and other requirements, called the Nasdaq Small Cap Market. Nasdaq will move companies from one market to the other as their eligibility changes.

During December 2005, Nasdaq acquired Instinet, the largest ECN and a large trader of Nasdaq-listed stocks.

On June 30, 2006, the SEC approved Nasdaq to begin operating as an exchange in Nasdaq-listed securities. Prior to this, as indicated above, Nasdaq had been an OTC stock market but not formally an exchange. This change is more technical then substantive.

Nasdaq was very acquisitive during 2007. During September 2007, Nasdaq agreed to buy the Middle East's Borse Dubai for approximately $4.9 billion. During August 2007 Nasdaq, after failing to acquire the LSE, partnered with Borse Dubai in the Middle East to gain control of Stockholm's OMX, which operates eight Nordic and Baltic exchanges. As part of the deal, Nasdaq sold its 28% position in the LSE to Borse Dubai, which ended up with nearly a 20% stake in Nasdaq. This acquisition made the Middle East's Borse Dubai a minority owner of the combined Nasdaq/OMX. With the purchase of OMX following its agreement with Borse Dubai, Nasdaq captured 47% of the controlling stake in OMX, thereby going closer to taking over the company and becoming a trans-Atlantic exchange.

During October 2007, Nasdaq also announced plans to buy the Boston Stock Exchange (for $61 million).

During November 2007, the Nasdaq Stock Market announced that it would buy the Philadelphia Stock Exchange for approximately $650 million, mainly to trade stock options. This was Nasdaq's first effort in stock options. Nasdaq, a purely electronic exchange, was expected to maintain Philadelphia trading floor.

The NYSE versus Nasdaq

Fundamentally, the NYSE has been an auction-type market based on orders (order driven), while Nasdaq has been a dealer-type market based on quotes (quote driven).

For decades, debates continued about which system—the NYSE or Nasdaq system—was most competitive and efficient. Those who think the Nasdaq OTC market is superior to the specialist-based NYSE often cite the greater competition from numerous dealers and the greater amount of capital they bring to the trading system. They also argue that specialists are conflicted in balancing their obligation to conduct a fair and orderly market and their need to make a profit.

Proponents of the specialist NYSE market structure argue that the commitment of the dealers in the OTC market to provide a market for shares is weaker than the obligation of the specialists on the exchanges. On the NYSE, specialists are obligated to maintain fair and orderly markets. Failure to fulfill this obligation may result in a loss of specialist status. A dealer in the OTC market is under no such obligation to continue its market-making activity during volatile and uncertain market conditions. Supporters of the specialist system also assert that without a single location for an auction, the OTC markets are fragmented and do not achieve the best trade price.

Another difference of opinion comes from traders who say that the specialist system may arrive at the better price, but take a longer period of time, during which the market price may move against the trader, or at least expose the trader to the risk that it will do so. The OTC market may, on the other hand, lead to a faster execution but not arrive at a better, market-clearing price. Professional traders, in this case, often prefer higher speed over better pricing. Retail investors on the other hand may prefer a better price.

While the NYSE has been an auction type/order driven market, it has adopted many dealer-type features. Similarly, while the Nasdaq has been a dealer type/quote-driven market, it has adopted many auction-type features. Thus, while distinct differences continue between these two markets, they have converged considerably and are both currently hybrid markets, although with different mixes of order-driven and quote-driven features.

Exchange Volume Data

This section illustrates the fragmentation of the trading of the stocks listed on an exchange among different trading markets.

During the 1980s, an exchange actually traded all stocks listed by the exchanges and only those stocks. Currently, however, stocks listed on one exchange can be traded by other exchanges, including regional exchanges, by nonex-change markets such as ECN, or via internalization markets, which are discussed below. For example, during the first week of January 2008, based on exchange data, of the 13,222,716 shares of NYSE-listed stocks traded during this week, 41.7% were traded by the NYSE Euronext and 12.3% by NYSE Arca. The remainder were traded by markets not related to the NYSE, including the regional markets, Nasdaq markets, and new stock markets such as the International Securities Exchange and Chicago Board Options Exchange, discussed below.

To generalize this dispersion (or "fragmentation") of trading of an exchange's listed stocks across multiple trading venues on a day in January 2008, according to exchange data, consider that:

Of the 4,634,118,176 shares of NYSE listed-stocks traded, 39.7% were traded on the NYSE and 12.8% were traded on NYSE Arca, for a total of 52.5% on NYSE affiliated markets.

Of the 2,573,601,692 shares of Nasdaq-listed stocks, 48.4% were traded on Nasdaq.

Of the 1,245,043,387 shares of Amex-listed stocks, only 3.4% were traded on Amex.

As indicated in the discussion on Regulation NMS later in this chapter, this increase in the fragmentation of trading among venues is likely to continue or even increase due to Regulation NMS.

The OTC market is often called a market for "unlisted" stocks. As described previously, there are listing requirements for exchanges. And while, technically, the Nasdaq has not been an exchange—it was an OTC market—there are also listing requirements for the Nasdaq National Market and the Small Capitalization OTC markets. Nevertheless, exchange-traded stocks are called "listed," and stocks traded on the OTC markets, including Nasdaq, are called "unlisted."

There are three parts to the OTC market: the two under Nasdaq and a third market for truly unlisted stocks, which are therefore non-Nasdaq OTC markets. The third non-Nasdaq OTC market is composed of two parts: the OTC Bulletin Board (OTCBB) and the Pink Sheets.

Thus, technically, both exchanges and the Nasdaq have listing requirements and only the non-Nasdaq OTC markets are nonlisted. However, in common parlance, the exchanges are often called the "listed market," and Nasdaq, by default, referred to as the "unlisted market." As a result, a more useful and practical categorization of the U.S. stock trading mechanisms is as follows:

Exchange-listed stocks

National exchanges

Regional exchanges

Nasdaq-listed OTC stocks

Nasdaq National Market

Nasdaq Small Cap Market (capital market issues)

Non-Nasdaq OTC stocks—unlisted

OTC Bulletin Board

Pink Sheets

The OTCBB, also called simply the Bulletin Board or Bulletin (often just the "Bullies"), is a regulated electronic quotation service that displays real-time quotes, last sale prices, and volume information in the OTC equity securities. These equity securities are generally securities that are not listed or traded on the Nasdaq or the national stock exchanges. The OTCBB is not part of or related to the Nasdaq Stock Market.

The OTCBB provides access to more than 3,300 securities and includes more than 230 participating market makers. The traded companies do not have any filing or reporting requirements with Nasdaq or FINRA, which is discussed later in the chapter. However, issues of all securities quoted on the OTCBB are subject to periodic filing requirements with the SEC or other regulatory authorities. Companies quoted on the OTCBB must be fully reporting (that is, current with all required SEC fillings) but have no market capitalization, minimum share price, corporate governance, or other requirements. Companies that have been "delisted" from stock exchanges for falling below minimum capitalization, minimum share price, or other requirements often end up being quoted on the OTCBB.

The Pink Sheets is an electronic quotation system that displays quotes from broker-dealers for many OTC securities. Market markers and other brokers who buy and sell OTC securities can use the Pink Sheets to publish their bid and ask quotation prices. The name "Pink Sheets" comes from the color of paper on which the quotes were historically printed prior to the electronic system. They are currently published today by Pink Sheets LLC, a privately owned company. Pink Sheets LLC is neither a NASD broker-dealer nor registered with the SEC; it is also not a stock exchange.

To be quoted in the Pink Sheets, companies do not need to fulfill any requirements (e.g., filing statements with the SEC). With the exception of a few foreign issuers (mostly represented by American Depositary Receipts, or ADRs), the companies quoted in the Pink Sheets tend to be closely held, extremely small, and/or thinly traded. Most do not meet the minimum listing requirements for trading on a stock exchange such as the NYSE. Many of these companies do not file periodic reports or audited financial statements with the SEC, making it very difficult for investors to find reliable, unbiased information about those companies.

For these reasons, the SEC views companies listed on Pink Sheets as "among the most risky investments" and advises potential investors to heavily research the companies in which they plan to invest. Buying Pink Sheets stocks is intended to be difficult. Broker-dealers are enjoined to weed out unsophisticated investors who may get an e-mail or word-of-mouth tip about a small stock.

Most OTCBB companies are dually quoted, meaning they are quoted on both the OTCBB and Pink Sheets. Stocks traded on the OTCBB or Pink Sheets are usually thinly traded microcap or penny stocks and are avoided by many investors due to a well-founded fear that share prices are easily manipulated. The SEC issues a stern warning to investors to beware of common fraud and manipulation schemes.

In general, options trading is composed of two components: (1) options on individual stocks (stock options) and options an indexes (index options).

Options exchanges are a combination of exchanges of two different origins. The first group began as options exchanges (and, as discussed elsewhere, diversified into stock exchanges). They are the Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) and the International Securities Exchange (ISE). The second group consists of stock exchanges that diversified into options exchanges. They are the American Stock Exchange, the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, the Boston Options Exchange (a subsidiary of the Boston Stock Exchange), and the New York Stock Exchange through its Archipelago holding, which had bought the Pacific Stock Exchange, which had added options to its original stock business.

With the acquisition of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, Nasdaq will join the NYSE as a newcomer in the options market.

A significant difference between stock and options trading is that stock trading is predominantly institutional, but stock options trading has a larger retail component, as shown below:

Institutional | Retail | |

|---|---|---|

Stock | 85%-90% | 10%–15% |

Options | 50% | 50% |

Since options exchanges are registered with the SEC, they, too, can initiate and operate stock exchanges. During 2007, the ISE and CBOE began stock exchanges, called the ISE Stock Exchange and the Chicago Board Options Stock Exchange, respectively.

The ISE Stock Market has two components, the first of which began during September 2006. The first component, called the MidPoint Match, is a nondisplayed market or "dark pool" (discussed below), where users can trade in a continuous, anonymous pool in which trades are executed at the midpoint of the national best bid and offer. The second component is a fully displayed continuous and anonymous electronic market wherein quotes are integrated in an auction market. Thus, investors can benefit from the interaction between a nondisplayed dark pool, the MidPoint Match, and the displayed liquidity pool. In this combination of systems, orders will have the opportunity for price improvement from the MidPoint Match system, or be executed or be displayed on the market's order book; or be routed out to other exchanges as required by the SEC's Regulation NMS.

Interestingly, the CBOE and ISE were options-only exchanges that subsequently developed stock exchanges. Some of the regional stock exchanges—Philadelphia, Boston, and Pacific—later developed options exchanges. In addition, the NYSE is in the stock options business through its purchase of Archipelago, which had previously bought the Pacific Stock Exchange. And Nasdaq entered the stock options business through its purchase of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange.

As explained earlier, the national and regional exchanges have continued to evolve and, in particular, have become much more electronically oriented. As of early 2008, however, a large volume of U.S. stock trading is done off any of the regulated stock exchanges. There has been significant growth and innovation in this sector of the U.S. stock markets in recent years. The off-exchange markets (also called alternative electronic markets) have continued to grow rapidly and become much more diverse.

Innovation in nonexchange (or off-exchange) trading began even before Nasdaq began. For example, Instinet began trading in 1969 and was essentially the first electronic communications network (although, as discussed below, it was not called an ECN until the late 1990s, when the SEC introduced the term as part of the development of its order-handling rules).

In general, these off-exchange markets are divided into two categories: electronic communications networks and alternative trading systems.

Electronic communications networks (ECNs) are essentially off-exchange exchanges. They are direct descendants of (and part of) Nasdaq, not the NYSE. ECNs are privately owned broker-dealers that operate as market participants, initially within the Nasdaq system. They display bids and offers; that is, they provide an open display. They provide institutions and market makers with an anonymous way to enter orders. Essentially, an ECN is a limit order book that is widely disseminated and open for continuous trading to subscribers, who may enter and access orders displayed on the ECN. ECNs offer transparency, anonymity, automated service, and reduced costs, and are therefore effective for handling small orders. ECNs may also be linked into the Nasdaq marketplace via a quotation representing the ECN's best buy and sell quote. In general, ECNs use the Internet to link buyers and sellers, bypassing brokers and trading floors. ECNs are informationally linked, even though they are distinct businesses. ECNs are subject to some best execution responsibilities including the SEC's Regulation NMS, which is discussed later.

Consider the background of ECNs. Instinet, the first ECN, began operating in 1969 before Nasdaq was founded in 1971. Instinet was designed to be a trading system for institutional investors (hence its name, which stands for "institutional network"). Instinet was viewed as an alternative to and competitor of the traditional Nasdaq dealer market. Instinet was intended to be a trading system for institutional investors, which allowed them to meet in an anonymous, disintermediated market.

Instinet seemed very similar to an exchange but was registered with the SEC, not as an exchange, but initially as a broker-dealer and subsequently as an ECN. Instinet took the position that they were just a broker-dealer that operated in the off-exchange ("upstairs") market as does any other broker-dealer that puts trades together for large customers. The only difference, according to Instinet, was that it operated electronically. This view emphasized the difficulty of distinguishing an exchange from a broker-dealer in a technological environment. The SEC acknowledged this difficulty by using a new category to apply to Instinet, that is, electronic communications Network, as discussed below when we explain order handling rules.

The number of ECNs increased considerably after the SEC imposed the order handling rules in 1997, as discussed below. As a result, ECNs significantly affected Nasdaq during the late 1990s after the SEC adopted its new order-handling rules in 1997. ECNs such as Archipelago, Brut, Island, and Instinet captured a majority of Nasdaq volume in about two years. Instinet acquired Island in September 2002.

Archipelago, which began operating in 1997, handles both institutional and retail order flow. Another ECN, Island, was primarily retail. Prior to these developments, all the off-exchange systems were designed for institutional customers.

As many as a dozen ECNs existed by early 2000. Then a wave of consolidations and acquisitions began that within only two years whittled that number down to a handful.

Some of the large ECNs were acquired—Instinet by Nasdaq during December 2005, and Archipelago by the NYSE during March 2006. Prior to its acquisition, Archipelago, an ECN at the time, acquired the Pacific Stock Exchange, to form a fully electronic stock exchange.

As of early 2008, there were a few ECNs operating; the largest is BATS, which provides trades to Nasdaq, the NYSE, the ISE, and some regional exchanges. BATS began in January 2006 and applied to the SEC to become a fully licensed securities exchange during 2007. Among the others are Direct Edge, Bloomberg, LavaFlow, and Track Data.

Prior to 2000, ECNs could not penetrate the NYSE-listed stocks as they did the Nasdaq market. The main reason was the impediment imposed by the NYSE's Rule 390, also called the order consolidation or order concentration rule. According to Rule 390, dealers who traded NYSE-listed stocks in the OTC could not be members of the NYSE. For this reason, only a few dealers actively participated in the OTC market for NYSE-listed stocks, and NYSE-listed stocks were traded mainly on the NYSE.

All central markets have incentives to impose order consolidation rules on their members. However, the SEC, to open up the NYSE market, pressured the NYSE to eliminate Rule 390. The NYSE eliminated Rule 390 in December 1999. This elimination exposed the NYSE to the same type of fragmentation to which Nasdaq had been exposed. But in the years immediately after the elimination of Rule 390, the NYSE continued to conduct most of the trading in its stocks; that is, the NYSE market did not experience nearly as much fragmentation as the Nasdaq markets. Subsequently, however, the NYSE has lost considerable market share to ECNs and other exchanges.

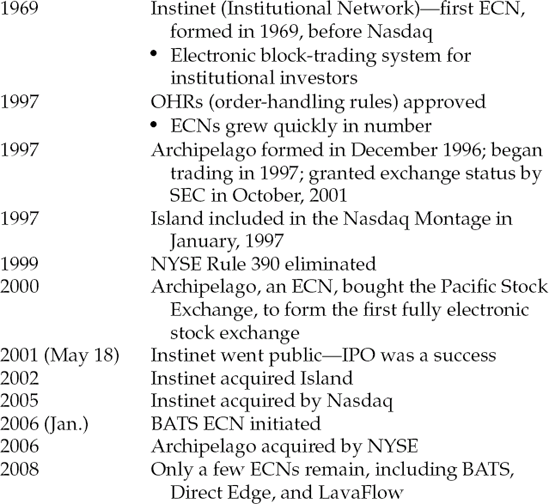

Some of the key events for ECNs are summarized in Figure 11.5.

In addition to ECNs, other alternative trading systems (ATSs) developed as alternatives to exchanges.

It is not necessary for two natural parties conducting a transaction to use an intermediary. That is, the services of a broker or a dealer are not required to execute a trade. The direct trading of stocks between two customers without the use of a broker or an exchange is called an ATS.

A number of proprietary ATSs have been developed. These ATSs are for-profit "broker's brokers" that match investor orders and report trading activity to the marketplace via the Nasdaq or the NYSE. More recently, such trades have been reported through Trade Reporting Facilities, as discussed later. In a sense, ATSs are similar to exchanges because they are designed to allow two participants to meet directly on the system and are maintained by a third party, who also serves a limited regulatory function by imposing requirements on each subscriber.

Broadly, there are two types of ATSs: crossing networks, which have functioned since the 1980s; and dark pools, which are much more recent.

Crossing Networks

Crossing networks are electronic venues that do not display quotes but anonymously match large orders. Crossing networks are systems developed to allow institutional investors to cross trades—that is, match buyers and sellers directly—typically via computer. These networks are batch processors that aggregate orders for execution at prespecified times. Crossing networks provide anonymity and reduce cost, and are specifically designed to minimize market impact trading costs. They vary considerably in their approach, including the type of order information that can be entered by the subscriber and the amount of pretrade transparency that is available to participants.

A crossing network matches buy and sell orders in a multinational trade at a price that is set elsewhere. The price used at the cross can be the midpoint of a bid-ask spread (such as the national bid and offer, as discussed below) or the last transaction price at a major market (such as the NYSE or Nasdaq) or linkage of markets. Thus, no price discovery results from a crossing network.

The major drawbacks of the crossing networks are (1) that their execution rates tend to be low and (2) that if they draw too much order flow away from the main market, they can, to their own detriment, undermine the quality of the very prices on which they are basing their trades. These limitations can be overcome in a call auction environment that includes price discovery.

ATS began developing during October 1987 when Investment Technologies Group's (ITG) Posit began. Posit is a crossing network that matches customer buy and sell orders that meet or cross each other in price (this is the way crossing networks were named) at a price established by the NYSE or the Nasdaq markets or the overall national market.

Another crossing network, LiquidNet, started operation in 2001. LiquidNet is an ATS that enables institutional customers to meet anonymously, negotiate a price, and trade in large sizes (average trade size is nearly 50,000 shares). Part of LiquidNet's ability to attract order flow is attributable to its customers' being able to negotiate their trades with reference to quotes prevailing in the major market centers. In other words, LiquidNet's customers do not have to participate in significant price discovery. Further, LiquidNet customers' anonymity and knowledge that counterparties in the system also wish to trade in size offers them some assurance that their orders will not have undue market impact. A key feature of the LiquidNet system is that customer matches are found electronically, and negotiations are also conducted electronically by the natural buyer and seller. LiquidNet has also developed in Europe.

Instinet, in addition to its continuous ECN, also developed an after-hours crossing, the Instinet Crossing Network. Instinet's after-hours cross was the first crossing network.

The Burlington Capital Markets, Burlington Large Order Cross (BLOX) also provides crossing systems. These systems enable institutions to trade with no price impact in a batched environment; the crosses are made at prices set in other stock market places. In addition, Harborside, which started operations in 2002, provides crossing services. These systems assist institutional customers to meet anonymously and negotiate their trades in an anonymous manner in an electronic environment that uses current quotes from external stock markets as benchmarks.

These crossing system are designed exclusively for institutional order flow. Among the major current crossing networks and their area of specializations are:

LiquidNet: for the buy-side to buy-side only.

Pipeline: for buy-side to buy-side block business only.

ITG Posit: provides timed crossings 5 to 10 times per day for buy-side to buy-side only.

BIDS: unlike the first three is an agency broker, that is it does not engage in proprietary trading and, thus, compete with its customers; launched in spring 2007.

Crossing networks have provided attractive alternatives to institutions to trade without their orders having any impact on the prices. However, due to lack of liquidity, their execution rates tend to be low, and if they draw too much order flow from the established markets, they could undermine the quality of the prices, which are the bases for the trades. In effect, crossing networks that use prices from the central stock markets to price their crosses are "free riding" on the price discovery of the central markets. These limitations could be resolved in a call-auction environment, which does provide price discovery.

In a call auction, sometimes called a period call, orders from customers are batched together for a simultaneous trade at a specific point in time. At the time of the call (in a "timed call") a market clearing price is determined—that is, there is a price discovery—and buy orders at this price and higher and sell orders at this price and lower are executed.

But the two systems based on call auction methods have not developed liquidity. The two ATSs based on call auction principles were the Arizona Stock Exchange (which started operations in 1991 and has been inactive since 2001) and Optimark (which started in 1999 and has been inactive since 2000). Neither of these systems succeeded in attracting critical mass order flow. Their experiences point up the difficulty of implementing an innovative new trading system that has to compete with an established market center, especially when the new system provides independent price discovery. These call auction systems provided price discovery and, thus, competed with established market centers and had difficulty attracting order flow.

Crossing markets are offered by some of the major broker-dealers who may also use such systems to "internalize" their order flow, that is match or cross bids and offers "upstairs," that is in their own organization. These orders may both be customer orders, or one may be a customer order that they cross with their own proprietary orders. A selection of the firms involved in internalization is Citigroup, Credit Suisse, Goldman Sachs, Lehman Bros., Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, and UBS.

Dark Pools

Another step in the evolution of nonexchange trading is the use of dark pools. Dark pools fulfill the need for a neutral gathering place and fulfill the traditional role of an exchange in the new paradigm. Dark pools are private crossing networks in which participants submit orders to cross trades at externally specified prices and, thus, provide anonymous sources of liquidity (hence the name "dark"). No quotes are involved—only orders at the externally determined price—and, thus, there is no price discovery.

Dark pools are electronic execution systems that do not display quotes but provide transactions at externally provided prices. Both the buyer and seller must submit a willingness to transact at this externally provided price—often the midpoint of the NBBO—to complete a trade. Dark pools are designed to prevent information leakage and offer access to undisclosed liquidity. Unlike open or displayed quotes, dark pools are anonymous and leave no "footprints." The advent of pricing in pennies led to less transparent markets and was, thus, instrumental in the initiation of dark pools.

Dark pools, as well as crossing networks, are creating very fragmented markets for large trades and block trades. Customers are also using algorithmic trading (discussed later) to respond to such hidden liquidity.

Among the advantages of dark pools are:

Nondisplayed liquidity.

Prevent information leakage (anonymous trading).

Volume discovery.

Reduced market impact.

Among the disadvantages are:

Less or no visibility.

Difficulty to interact with order flow.

No price discovery.

The sponsors of dark pools can be:

Exchanges (e.g., NYSE Euronext, the Nasdaq stock market, and the International Securities Exchange).

Broker-dealers (e.g., Credit Suisse, Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Merrill Lynch, and others; can be used for brokerage internalization).

Independent organizations (e.g., Instinet, Liquidnet, Pipeline Trading Strategies and Investment Technologies Group (ITG) Posit).

Consortia of other organizations.

Summary of the Structure of the Mechanisms for Equity Transactions

In this section, several mechanisms for transacting equities, both conceptual and actual, have been discussed. Figure 11.6 summarizes the structure of the mechanisms for equity transactions. While the exchange markets continue to evolve, the off-exchange markets also continue to grow, diversify, and add advantages to the overall market. ECNs are used for either institutional or retail order flow, while crossing networks and dark pools are used mainly for institutional order flow.

Another difference between sectors of the off-exchange market is that ECNs are quote driven, while crossing networks and dark pools are order driven. One disadvantage of these off-exchange markets is that they tend to fragment the overall market, that is, remove quotes and trades from the central exchange markets.

Some analysts observe that there is a hierarchy in the quality of execution, with ATS being the highest, ECN being next, and exchanges being the lowest. Some analysts say that the exchanges are getting the so-called "exhaust" of executions.

This section discusses recent changes in the NYSE. The section focuses on the NYSE because of the significant recent changes in its market structure, advances in technology, ownership, and acquisition of other market venues.

For years, even decades, the NYSE gradually increased the use of electronic trading to supplement it specialist-based, human-touch trading. Then, during 2006 and early 2007, this evolution turned into a revolution.

During the previous years, the functionality and capacity of DOT and SuperDOT, discussed earlier, continually increased, reducing the need for specialist intervention for a larger number of trades. A significant indication of the rapid change in the need for specialist-oriented NYSE floor space was that a new NYSE trading room that was opened at 30 Broad Street during October 2000 was closed in February 2007.

There were several components of this revolution. The two major components were as follows. First, in December 2005, the NYSE initiated its NYSE Hybrid Market, which gave customers the choice of the traditional auction-based specialists system or new electronic trading. The basis for the electronic component of the NYSE Hybrid Market was NYSE Direct+, an automatic execution service, the pilot of which was launched in October 2000 and which was expanded in August 2004.

Second, the crescendo of this revolution occurred in March 2006. On March 7, the NYSE merged with Archipelago Holding Inc. (commonly called "Arca") and, as a result, became a for-profit, publicly owned company. On the following day, the shares of the newly formed NYSE Group began trading on an exchange—the NYSE, of course. As a result, there were no more NYSE memberships or "seats" (which reached a high of $4 million in December 2005). These seats were replaced by NYX shares as a measure of value and "access" rights for floor trading privileges became available separately.

The period 2006–2007 was exceptionally active for the NYSE. Specifically, the major events during this period were as follows:

On March 3, 2006, the NYSE bought Archipelago Holdings, a publicly owned, for-profit exchange (Arca was granted exchange status by the SEC on October 20, 2001). Archipelago bought the Pacific Stock Exchange during January 2005. NYSE Group Inc., a public company, was formed out of the merger of NYSE and Archipelago.

On the next day, NYSE Group Inc. conducted its IPO and began trading (ticker symbol: NYX; initial price: $67). Thus, the IPO was arranged in conjunction with the acquisition of Archipelago.

Over the period from October 2006 to January 2007, the NYSE introduced the NYSE Hybrid Market, a blend of an auction and an electronic market. Archipelago remained a distinct electronic market.

On April 4, 2007, the NYSE Group completed a merger with Euronext NV, a Paris-based European stock exchange, making the NYSE the first trans-Atlantic exchange group. Thus, the NYSE became a global company by buying Euronext. The NYSE went public later than many other exchanges but became an international company before many others.

Thus, during a brief period from 2006 to 2007, the NYSE went public, initiated a hybrid market, and became global.

While the NYSE Hybrid was introduced in the period from October 2006 to January 2007, it was based on systems initiated and developed previously. Some of these are described below:

Table 11.1. Summary of Key NYSE Events

1976 | Designated Order Turnaround (DOT) initiated |

October 2000 | Direct+ initiated |

January 2002 | OpenBook initiated |

March 7, 2006 | NYSE buys Archipelago; becomes public company named "NYSE Group Inc." |

March 8, 2006 | NYSE conducts IPO; listed on the NYSE with ticker symbol NYX |

October 2006-January 2007 | NYSE Hybrid Market initiated on January 24, 2007 for all NYSE stocks (except for a few high-period stocks). |

April 4, 2007 | NYSE completes merger with Euronext; now named "NYSE Euronext." |

Designated Order Turnaround Systems (DOT and SuperDOT). This system allows brokers to route orders, usually retail orders, directly to the specialist posts or the trading floor for execution. The original DOT system was initiated during 1976 and has been continually expanded and improved.

Direct+. In October 2000, the NYSE introduced this system, which is an automatic execution service on limit orders up to 1,099 shares at the published NYSE quote. The only option for market orders was the standard method. NYSE Direct+ was subsequently expanded and became the foundation on which the electronic component of the NYSE Hybrid Market was built.

OpenBook. In January 2002, the NYSE introduced this system, which provides limit order book information to traders on the exchange floor. This was the first step in opening the previously closed specialist's order book.

A summary of the key dates and activities is summarized in Table 11.1.

The remainder of this section provides additional information on these elements of the NYSE Hybrid Market and the overall Hybrid market.

Designated Order Turnaround Systems (DOT or SuperDOT)

Traditionally, the NYSE has conducted its execution via the specialist system wherein the specialists execute orders presented by floor brokers. However, as explained earlier, the use of electronic trading has continually increased. The key mechanism for electronic trading has been the DOT or SuperDOT.