LARRY SPEIDELL, CFA

General Partner, Ondine Asset Management, LLC

JARROD W. WILCOX, PhD, CFA

President, Wilcox Investment Inc.

Abstract: The emerging market phenomenon tends to come to our attention most after extremely good or bad returns, but it is a pervasive long-term process of better returns and useful diversification stretching over many decades. It can be understood in terms of innovation diffusion and the several factors that influence it: awareness of, resistance to, and ability to implement new ideas through entrepreneurial activity, combined with increasing transparency, liquidity and low barriers to capital movement that allow globalization of portfolios. There are strong theoretical reasons for expecting relatively high risk-adjusted returns to the fully diversified long-term global investor. Diversification opportunities are best within the frontier markets, both within this group and relative to the developed country investor's home market. Remaining emerging market inefficiencies appear to offer relatively more scope for active management than do large capitalization markets in the United States and other developed markets, but they require old-fashioned attention to detail for their full exploitation.

Keywords: emerging markets, diversification, innovation diffusion, globalization, portfolio construction, demographic, industrialization, population, transparency, corruption, bureaucracy, World Bank, International Finance Corporation (IFC), Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI), frontier markets

Investments in the emerging stock markets have become an important part of many portfolios in the more developed world. The likelihood of continued rapid growth in countries such as China, India, Russia, Brazil, and many smaller, less developed markets has become widely recognized. How should we as investors think about these markets? To clarify this issue, we first identify the members of this group, their long-term transitional economic process and why it may be expected to continue. Then we discuss their investment characteristics. We fill out this framework with discussions of why progress in individual countries may stall, some practical details of investment, and the variety of investment strategies commonly employed. Our treatment is from the viewpoint of the practitioner, incorporating broad nonfinancial qualitative description and analysis, but references to quantitative academic work are also provided.

Many less developed economies in countries with collectively large populations are becoming industrialized, increasing their rate of growth in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and becoming stable and open enough to attract global investors from developed countries. This process, once fairly begun, appears to be self-reinforcing.

The dawn of the modern age of investing in emerging markets came in 1987 with the introduction of the emerging stock market indexes of Capital International Perspective (now Morgan Stanley Capital International [MSCI]). At about the same time, the International Finance Corporation (IFC), part of the World Bank, began introducing country funds, hired managers to create specialized funds targeted at Malaysia, Thailand, Brazil, and other countries in Asia and Latin America. The IFC pioneered in the development of many new capital markets around the world. These efforts have born greater fruit than most observers would have predicted.

In the mid-1980s, it would have been very difficult to predict the rapid demise of the Soviet Union and the new freedoms that came to Eastern Europe. Equally surprising was the statement by Deng Xiaoping that "it doesn't matter if the cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice." That remark made capitalism legitimate in Communist China and led to an unparalleled economic revolution that has raised living standards for over 1 billion people.

For practical investing purposes, the emerging markets may be considered in three categories: the MSCI emerging markets countries, the frontier markets (those countries outside the MSCI EM Index that have stock markets), and the less developed countries that do not have stock markets.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index is a free float-adjusted market capitalization index that is designed to measure equity market performance in the global emerging markets. In 1987, the Index consisted of eight countries. The list has expanded greatly as more countries have created viable stock markets. As of June 2006, the index included the following 25 countries: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Jordan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, and Turkey.

Despite the name "emerging," only one country has so far emerged to MSCI developed status—Portugal. Another, Malaysia, was anointed with developed world status from 1993 to 1998, but lost it when its stock market was shuttered to foreign investors in response to the Asian currency crisis. Table 13.1, however, leaves many active stock markets out of the emerging markets "club," including Sri Lanka and Venezuela, which were expelled, as well as Middle East markets such as those of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—though these are also now included in the Morgan Stanley Capital International Frontier Market Index.

In addition, over 60 other countries have some kind of stock market of interest to global investors. Many of these are followed in the S&P/IFC database of frontier markets—Bangladesh, Botswana, Bulgaria, Cote d'Ivoire, Croatia, Ecuador, Estonia, Ghana, Jamaica, Kenya, Latvia, Lebanon, Lithuania, Mauritius, Namibia, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Trinidad & Tobago, Tunisia, Ukraine, and Vietnam. Other frontier markets include Costa Rica, Mongolia, Malawi, Nigeria, Zambia, and many more. Many additional countries yet have no stock markets. Not all countries with stock markets are freely open to foreign investors, but many countries that are outside the mainstream MSCI Emerging Markets Index may nevertheless deserve global investor attention.

Table 13.1. MSCI Emerging Markets Index Constituent Countries

Country | Date Added | Changes |

|---|---|---|

Source: MSCI. | ||

Argentina | 1988 | |

Brazil | 1988 | |

Jordan | 1988 | |

Malaysia | 1988 | Developed 1993-1997 |

Philippines | 1988 | |

Thailand | 1988 | |

Mexico | 1988 | |

Greece | 1989 | |

S. Korea | 1989 | |

Portugal | 1989 | Developed since 1997 |

Taiwan | 1989 | |

Indonesia | 1990 | |

Turkey | 1990 | |

Colombia | 1993 | |

India | 1993 | |

Pakistan | 1993 | |

Peru | 1993 | |

Sri Lanka | 1993 | Removed in 2001 |

Venezuela | 1993 | Removed in 2006 |

China | 1995 | |

Israel | 1995 | |

Poland | 1995 | |

S. Africa | 1995 | |

Russia | 1996 | |

Czech Rep | 1996 | |

Hungary | 1996 | |

Egypt | 2001 | |

Morocco | 2001 | |

At the end of the 1980s, the Iron Curtain and the Soviet Union collapsed, ushering in a period of euphoria over emerging markets. Communism had been discredited as an economic engine, politicians and businessmen seemed committed to market-based reforms, and there was a virtuous circle of rising capital flows, falling capital costs, rising liquidity, falling volatility, and strong economic growth.

However, the optimism of many investors proved to be naïve. Beginning with the Mexican peso crisis in 1994, the world of emerging markets was rocked by the Asian crisis, the Russian Crisis, and several crises elsewhere, including Argentina, Brazil, Venezuela, and Turkey. Some blamed "crony capitalism." Others blamed inexperienced investment bankers who peddled deals that were bound to fail. Inadequate regulations and ineffective currency policies also played a role.

Yet economic growth rates for emerging countries still generally exceeded those of the developed world. According to the World Bank (2005), in the period from 2000 to 2005, the United States had average real GDP growth of 2.8%, EAFE countries had 2.6%, Emerging Markets (in the MSCI EM Index) had 4.4%, and Frontier Countries had 4.3%. Some countries have done much better than the average, with China having an annual growth rate of 9.3%, Kazakhstan 10.2%, and Armenia 11.0%. Among others showing excellent growth were Latvia (8.1%), Ukraine (7.4%), Vietnam (7.4%), and Tanzania (6.6%).

The Internet and other improved communications technologies provide education, business, and job opportunities in emerging countries that never had them before. Possibly most at variance with prior expectations is the outsourcing from more developed countries of jobs in fields such as technology, software, customer service, and medical diagnostics. Also supporting this development process has been the mobilization of labor from less productive rural areas to more productive urban and industrialized environments. Just as the past 150 years saw massive migration from farms to factories in the developed world, this migration is happening now in the emerging world. In China alone, nearly 20 million people a year are reported moving from rural villages to urban centers. A somewhat slower but still comparable movement is occurring in India.

On the other hand, countries must compete for capital, and some emerging countries will not quickly succeed. Global investors can be fickle and alter capital flows promptly at signs of trouble. Some countries have difficulty grasping this concept. After the fall of the Iron Curtain and the breakup of Czechoslovakia, one of the authors was part of a delegation that met with senior government ministers in Bratislava, capital of Slovakia. They wanted to attract foreign capital and described their companies as "sleeping beauties, awaiting the kiss of foreign investors to awaken." Sadly, the factories they spoke about were moribund Soviet-era tank factories, old industrial plants, and inefficient steel mills.

Many investors still harbor unfavorable images of emerging markets—images of dangerous working conditions, children picking through garbage to survive, inefficient factories belching pollution, and corrupt governments siphoning off their country's wealth into personal Swiss bank accounts. These problems do exist, but they are not the whole story.

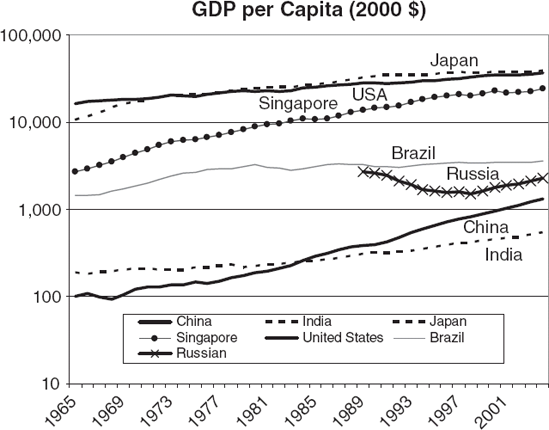

Some past success stories of countries in transition are illustrated in Figure 13.1. According to the World Bank, over the 40 years through 2004, Japan's per capita GDP rose in U.S. dollars (constant year 2000) from $10,615 to $38,609 versus a rise for the United States from $16,416 to $36,655. Even more dramatically in percentage growth terms, Singapore's per capital GDP rose from $2,675 to $24,164. Over the same period, China has outpaced India: from $100 to $1,323 versus $187 to $538. Finally, one can see the trials that Russia has endured on its way from Communism to today's free-for-all capitalism: GDP per capita dropped from $2,693 in 1989 to $1,564 in 1996 before recovering to $2,286 in 2004.

One way to understand the emerging market process is to think of it in terms of a "contagion" model, producing the familiar S-shaped curve of innovation diffusion. Ideally, the transition of people to advanced market-based economies from traditional and command economies is a function of their exposure to the perceived relative attractiveness of the standard of living available through free-market capitalism and its supportive legal and political structure. In the real world, this picture is complicated by barriers to idea communication and receptivity, by lack of capacity to initiate implementation of different ideas, and by lack of resources, including time, to build up the physical and social infrastructure necessary to carry them out fully. Barriers to trade instituted by developed countries threatened by new competitors can also be a factor. But the process will continue at least as long as the gap in standard of living is perceived and the barriers of poor communication, disbelief, incapacity to initiate, and lack of resources keep falling.

How do the reservoirs of population, industrialization, and stock market value stand?

According to the World Bank, in 2006 the world stood very unequally divided. Emerging countries had 82% of the world's population, 77% of the land mass, only 32% of GDP (though 52% adjusted to purchasing power parity), and yet only 8% of world stock market capitalization. It is clear that the reservoir of the undeveloped economy is still much larger than that of the developed economy, and the higher population growth rate in less developed countries suggests that situation will endure for many years. The potential for transition remains enormous.

If one were to project current high relative growth rates into the future, as, for example, Jeremy Siegel (2005) does, it would imply that 77% of world GDP (purchasing power parity basis) will come from emerging countries in 2050, and they will account for 67% of world stock market capitalization. This does not imply that the transition will be smooth; in a process involving both rapid growth and high uncertainty, cycles of boom and bust along the way are to be expected.

To further justify confidence in high economic growth rates from "catch up" in many of today's emerging markets, we may examine the factors that govern the rate of "contagion."

Appeal

The appeal offered by market-oriented societies of both a much higher material standard of living and greater opportunity for personal advancement is intact, despite widespread resentment of what is often perceived to be cultural imperialism. The proof is that whenever barriers to communication and emigration are removed, significant portions of the population have voted with their feet.

Communication

Widespread global interest in motion pictures, television programs, and popular music originating in the advanced economies has occurred wherever the facilities for its expression are made available. A technological revolution in the means of communication based on mobile phones and the Internet still has far to go in many countries before reaching saturation points, but is moving steadily forward. As means of communication reach rural areas, farmers and small business people are empowered. Fisherman in India now use mobile phones so they can deliver their catch to the village paying the highest prices rather than seeing it spoil where there is a glut. The potential for global education through projects such as "One Laptop per Child" is enormous and largely untapped.

Acceptance

The fall of the Berlin Wall was a milestone in the recognition of the futility of holding back transition to market-based economies by the command governments in Eastern Europe and in the former Soviet Union. However, the real power behind the movement may have been the appeal of demonstrations by other countries in transition. In Europe, the success of the Common Market and its successors and the economic resurgence of West Germany were models. In Asia, the economic revival of Japan, followed by South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, demonstrated what could be done. Others observed and learned.

In many countries today, nationalistic resentment, religious reaction, and understandable dissatisfaction with capitalism's excesses if poorly governed, might make it seem that globalization of marketplace values is stalled. This is apparent in parts of the Middle East, Africa, and South America. Nevertheless, the large populations of China and India appear fully committed to transition, and it will be hard to argue with their demonstrated success in the future.

Capacity to Innovate

It does no good to learn of technological advances unless there is a capacity to innovate. To accelerate innovation, markets must be allowed to make decisions long made by governments or by an elite. Those in high status positions can no longer be as protected by the status quo. At the most basic level, there must be escape routes from abject poverty for small businesspeople and entrepreneurs.

High birth rates, even if not supported by social strictures, keep women from participating fully in the trading economy; high birth rates are characteristic of low income levels. Lack of even primary education and means of communication and transportation closes channels for specialization in production where the output could be traded. The rule of man rather than that of law reduces the incentive to develop valuable economic assets. All these barriers are falling, as evidenced by United Nations and World Bank data, not everywhere, but in many places. The success of micro financing demonstrates the potential here.

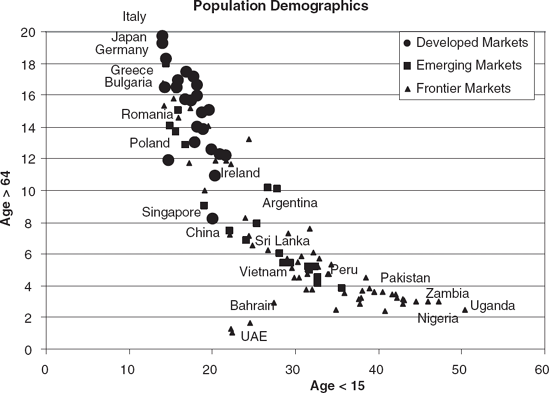

Population changes are glacial but powerful. Many countries in the developing world, and almost all in the developed world, have falling birth rates and increasing life spans. For developed countries, the portion of workers over age 65 is already high, and projections by the United Nations Population Division show these percentages reaching even higher levels, especially in Japan and Europe over the next 40 years (nearly one dependent per worker in Japan). Meanwhile, by mid-century, populations will likely be actually shrinking in Japan, Russia, Europe, and China. The opposite problem exists in most emerging markets today—too many very young people. Birth rates, though they are falling, are still very high. In Pakistan, for example, 41% of the population is under age 14. It seems likely that this demographic is an aggravating factor, along with inequalities in income heightened by economic transition, underlying the instability in political and economic conditions in these countries. With economic growth and natural maturation, these populations of youth are likely to assume a more productive and stable economic role over the next two decades. They may, in fact, be needed to do much of the economic heavy lifting for the aging populations in the developed world.

From GDP to Market Value

For many years, the International Finance Corporation has produced a chart that shows that the size of a country's stock market versus its level of GDP per capita. The inference of causality indicates that as economies make real progress measured by incomes, they tend to develop more sophisticated financial markets, including larger stock markets. For example, a change in per capita GDP from $1,000 to $5,000 would imply a change in the stock market value from 28% of GDP to 66%. Thus, a five times increase in GDP per capita suggests that the stock market capitalization might grow by over 10 times.

The logic we use for understanding why the emerging market process will continue may be equally valuable in understanding what causes its progress to move in fits and starts, and in some locations far more rapidly than in others.

Communication and Receptiveness

Market-oriented ideas can be extremely disruptive of the social fabric. If capitalism is unrestrained by government, it can produce staggering income inequalities as well as periodic mass unemployment. At the other end of the social scale, the required openness to the rise of new entrepreneurs and increased competition may prove disruptive to the power and privileges of existing elites. Apparently, this extends to political and religious spheres, and even to family relationships. Social disruption naturally causes resistance by those who lose thereby.

Economic Policies Affect Entrepreneurship

The 2007 Economic Freedom Score published by the Heritage Foundation ranks each country in terms factors such as regulations, size of government, labor, trade, fiscal and monetary policies, property rights, and corruption. The average score for 75 developed, emerging, and frontier countries has improved from 60.2 in 1995 to 63.7 in 2007, with gains in all categories, as shown in Table 13.2. There have been glaring exceptions, such as Zimbabwe and Venezuela, but most countries are moving toward conditions allowing entrepreneurship greater scope. But the investors might have profited if they could have predicted backsliding in this respect by the countries' shown in Table 13.3.

Table 13.2. Economic Freedom Ranks

Heritage Freedom Score 1995 | Heritage Freedom Score 2007 | |

|---|---|---|

Source: The Heritage Foundation. | ||

Developed countries | 72.3 | 75.9 |

Emerging markets | 60.1 | 61.5 |

Frontier markets | 55.6 | 60.2 |

Table 13.3. Changes in Economic Freedom Score

Country | Heritage Rank Change (2000-2007) |

|---|---|

Source: The Heritage Foundation, 2007. | |

Peru | −5.3 |

Morocco | −5.6 |

Paraguay | −5.7 |

El Salvador | −5.9 |

Turkey | −6.8 |

Venezuela | −8.1 |

Zimbabwe | −8.6 |

Bolivia | −10.4 |

Bahrain | −10.8 |

UAE | −14.5 |

Argentina | −16.7 |

Table 13.4. Corruption Perceptions Index, Transparency International

2005 CPI Score | Chg 2000-2005 | |

|---|---|---|

Developed countries | 8.22 | 3.4% |

Emerging countries | 3.90 | −0.1% |

Frontier countries | 3.71 | 2.6% |

Corruption Affects Entrepreneurship

Corruption is a block to growth, a deterrent to foreign investors and a parasite that threatens to destroy its host. Those apologists who claim that corruption is cultural need only look to Singapore, surrounded by Asian neighbors where corruption is high. Singapore has insisted on integrity ... and has enjoyed one of the world's highest economic growth rates.

Transparency International uses its own surveys as well as other sources to compile the Corruption Perceptions Index. It gives highest scores to the best countries, such as Iceland and Finland, and the lowest to those where corruption is the worst, like Haiti. Clearly, emerging and frontier countries have a long way to go to catch up with the developed world, as shown in Table 13.4. Still, the picture is not as bleak as it may seem, because the performance of emerging countries was clouded by declines in a few countries: Venezuela, Argentina, and Poland.

Bureaucracy Affects Entrepreneurship

The World Bank measures several dimensions of the costs of doing business, such as the number of procedures required to start a new business and the fees required relative to average incomes, but the most dramatic is the number of days required before one can open a business legally in different countries. It is an astonishing 152 days in Brazil versus two days in Australia!

Violence affects the entire process of economic transition. The daily news seems as filled as ever with news of violence, but the work done by the Human Security Center in conjunction with Uppsala University's Conflict Data Program and the International Peace Research Institute, Oslo (PRIO) indicates that violent global conflicts have declined from a peak over 50 in 1992 to 30 in 2002. (See Harborn, Hogbladh, and Wallensteen, 2006.) Despite the recent trend downward, anywhere violent conflict breaks out, normal economic progress is severely disrupted.

To fully understand the appeal of emerging markets to developed country investors, we need to look beyond the good financial performance of recent years. We can examine the factors that have tended to increase returns and may do so over a longer period, as well as those that have tended to reduce risks when viewed in a total portfolio context. How have these markets performed?

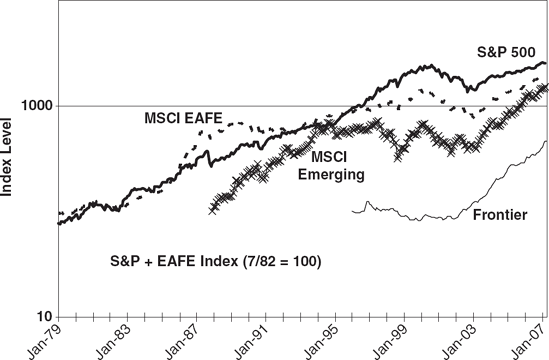

As we can see in Figure 13.3, from 1987 to 1994, emerging market returns were strong, as the Iron Curtain fell and the emerging market "asset class" became recognized. From 1994 to 2002, the markets moved sideways under the burden of persistent financial crises (the peso, the ruble, the baht, etc.). From 2002 to 2007, both the Emerging Markets Index and the Frontier Markets Composite have done well. Over long periods, emerging markets have provided superior returns as compared to both the S&P 500 Index and the MSCI EAFE index of developed country stock markets, but at the cost of extended periods of retreat. This has led to disappointment during downturns, and viewed in isolation, some investors continue to find the risk/reward ratio unappealing.

The simple story is one of the impact of globalization. Economically advanced practices spread from places where they benefit only a few people to places where they benefit the great majority of the world's population. Being less developed, emerging market countries can catch up simply by copying developed nations; being poor in the age of television, their people can see what the rich nations have and become motivated to achieve it; and being home to 84% of the world's population, emerging nations can gain support from developed nations to avert the specter of global violence in a nuclear age. We know that such growth stories can become the stuff of overvaluation and even speculative bubbles. There will be setbacks. However, the longer-term trend is clear.

Markets can be rather efficient in incorporating information into prices. Why then, should we believe that current prices of emerging market stocks have not already reflected this prospect? The following two factors should be considered.

Market Inefficiency in Pricing Long-Term Changes

Suppose one believes that markets are more efficient in pricing information regarding near-term events and less efficient regarding longer-term trends. This might be because no knowledge exists regarding the longer-term future. Alternatively, it may be because such knowledge of longer-term trends is not as widely shared, or because some decision makers do not care to anticipate events stretching beyond their lifetime as active investors. As with climate change, running out of cheap oil and other foreseeable long-term events, most investors appear to wait until major changes become self-evident before reacting.

Emerging markets have some of the flavor of this kind of phenomenon. The economic catch-up period for an economy once it has been opened up to market forces is quite long. For example, it has been two decades since the fall of the Berlin Wall, yet the former East Germany is still considerably behind West Germany in economic development. Moreover, that has been in a favorable circumstance of common language, a common national government, and heavy capital inflows. Where cultural gaps are larger, we may with reason expect much longer periods of transition. It would be requiring a great deal for markets to be sufficiently farsighted to adequately discount even a single generation's accelerated economic progress.

Segmentation

The second factor is that there remain barriers to investment, not only for the global investor trying to put funds to work in the emerging market, but more importantly, for local investors to diversify abroad. Can we expect investors in Malaysia or Turkey or Brazil to be efficiently diversified globally? Lack of knowledge, language barriers, and government intervention through capital controls are common. In other words, emerging markets retain country and regional segmentation. For the local investor with less effective diversification, higher risks require compensation in the form of higher returns (Merton, 1987). The global investor with superior access to financial intermediaries and information can more effectively diversify and consequently take advantage of these higher returns with less sacrifice in risk.

It is possible that lower apparent prices for existing assets also reflect inflated accounting. However, the higher return requirements caused by segmentation, higher interest rates reflecting increased risk even after diversification, and the behavioral biases of global investors all suggest there is still room for further convergence for existing emerging markets. In addition, there are more countries waiting in the wings.

The Issue of Valuation

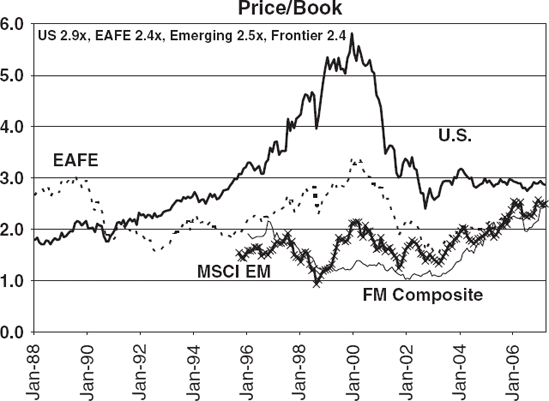

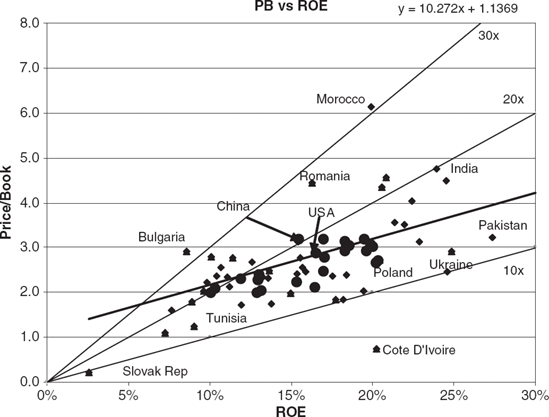

An interesting phenomenon in recent years has been the convergence of valuations around the world, illustrated by the chart of price-to-book ratios in Figure 13.4.

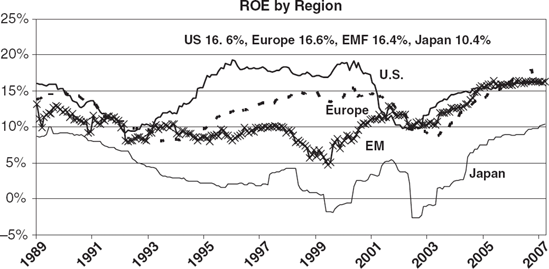

The convergence in price-to-book ratios since the end of 2002 appears to have been driven by an improvement in the quality of markets and companies themselves and is reflected in a narrowing of returns on equity in the different market sectors. For example, in March 2007, the return on equity (ROE) of MSCI Europe and the United States was identical, at 16.6%, while emerging markets were close, at 16.4%, and frontier markets were at 13.4% (Japan was still low at 10.4%, but much improved from zero in 2003).

When we look at risk in isolated security or even country return characteristics, most emerging markets appear very risky to the developed country investor. Not only past return volatility but also future uncertainties as to government policy and the possibility of political disruption can create a daunting prospect. However, the risk picture is considerably alleviated when we consider a diversified basket of different emerging markets, and it is even more favorable when we consider the diversification potential of such a basket relative to developed country investments.

Risk Evolution

As individual country markets become more mature and fully integrated into global capital markets, volatility tends to decline, but simultaneously the benefit of low return correlation is also reduced as return correlations increase. For some investors this has meant the investments have become more mainstream and acceptable; others find that they must continually seek out the least developed markets, perhaps today's frontier markets, to get the full diversification and long-term return benefits.

Volatility

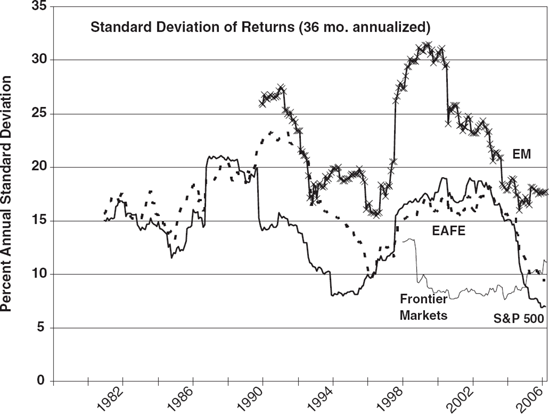

Countering the tendency for correlations with developed country correlations to increase in the countries where globalization has overcome preexisting segmentation, there is the benefit that the volatility of baskets of emerging markets has fallen. Consider Figure 13.6. Although volatility was high during the 1990s, the 36-month standard deviation of monthly returns for the MSCI emerging-market basket has recently fallen from over 30% to 17.7%.

Paradoxically, although frontier markets have high volatilities individually, when we look at the S&P/IFC Composite of 22 frontier markets, their return volatility as a group is only 11.1%, lower than MSCI emerging markets and close to that of the EAFE Index. This surprising result is due to the low return correlations among the frontier markets themselves. Botswana is not influenced by Bangladesh, and neither market cares much about what is happening in Bulgaria.

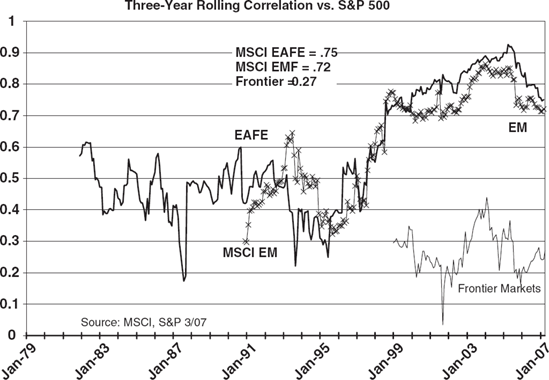

Correlations

Return correlations of most stock markets with one another have been rising over the past 20 years, due to the globalization of economies and the globalization of investing. As Figure 13.7 shows, the correlations of both the EAFE Index and the Emerging Markets Index with the S&P 500 have risen from 1986 to 2006, from roughly 0.50 in the 1980s to 0.75 and 0.72, respectively, recently. This appears to be a consequence of the rising popularity of global investing.

The earlier R-squared (the correlation squared or coefficient of determination) of 0.25 for emerging markets implied that only 25% of the movement of emerging markets in the 1980s was related to movement in the S&P. Since about 2000, R-squared has risen to about 0.5, implying that there is still significant diversification, but it is not what it used to be. Still, the return correlation of the MSCI Emerging market index with the S&P 500 is lower than that for the developed countries, as represented by the EAFE Index. If we look at the markets of countries very early in the transition to market development, the "frontier markets," the correlations remain very much lower. For the Frontier Markets Composite, the correlation is quite low, at 0.27, giving an R-squared of only 0.07, although both could be expected to rise as these markets become more popular.

In this section, we discuss some of the practical obstacles facing the global investor. Some of these are macro challenges—the destruction of shareholder value during the prosecution of Russian Mikael Kordokovsky and the de facto nationalization of his oil company Yukos, and the economic ruin brought on by "big men" rulers in Zimbabwe and Kazakhstan are not isolated examples.

However, many obstacles are niggling details that add up in total. In frontier countries, simply getting annual reports can be difficult. Once published, often many months after year-end, they may not be posted on the company's web site (if there is one) for a year, and companies rarely respond to emailed requests for them. Once annual reports are obtained, they are often short and lacking in candid comments about the business outlook. The financial statements can be hard to interpret, with obscure accounting treatments and local terms such as "headline earnings" or "embedded value." In the case of initial public offerings, the planning and execution can be quite different from procedures in more developed markets. For example, a recent road show for an African bank failed to provide the prospectus, then commitment funds were tied up for two months before allocations were made and, finally foreign investors were allocated only $4,000 each. Local company visits can be very difficult, given the challenges of primitive local infrastructure and logistical challenges. Conference calls can be useful, but phone service to many frontier countries is poor and intermittent. Moreover, language barriers can exist even when both parties believe they are speaking the same English language!

Research reports can be hard to find as well, and their quality varies widely. Although the number of analysts who have passed the Chartered Financial Analyst examinations is growing rapidly in emerging countries, many reports on local companies are too often simply just reports: brief and factual rather than analytical and insightful. Financial forecasts are frequently lacking—in Bangladesh, they are even forbidden. Ask a local broker about his or her market, and the first stocks you will hear about are the biggest, because they would like you to do a large trade. Ask about their favorite stocks, and you will hear about the three stocks that went up the most in the past year. Ask again and you may hear about an obscure name that is cheap but rarely trades. These challenges mean that market prices may be extremely inefficient, but it takes diligence and patience to find the most attractive buy candidates.

Then there are issues of market access. Opening a local account can require coping with sluggish bureaucracy and Byzantine regulations. There can be local limits on foreign purchases: For example, until recently only one stock in Tanzania was below the 60% foreign ownership limit. Placing orders presents challenges too, with close monitoring needed to prevent them from being "lost," executed in the wrong stock or executed with unexpectedly high currency conversion charges. Initial public offerings may favor local investors, sometimes practically excluding foreigners who nevertheless have their commitment funds tied up for months. Finally, commission costs can be as high as 200 basis points in Bulgaria, Cote d'Ivoire, and Romania, 250 basis points in Zambia, 275 basis points in Nigeria, and 300 basis points in Ghana and Montenegro.

Participation in emerging stock markets through a broad-based index fund or exchange-traded fund (ETF) is the most sensible approach for many investors. Language differences, lack of information, and high fees and transaction costs make passive investments in emerging markets through index funds, ETFs, and a basket of country funds the most widely used approach. On the other hand, because emerging markets remain quite inefficient in terms of security pricing, active management can be relatively more rewarding than in more efficient developed markets. The challenges are greater in assembling a basket of securities in frontier markets, but for large investors they can be approached through investment limited partnerships and special funds licensed for foreigners. For active investors, not only country funds, but for some of the larger emerging market stocks traded in the United States or London, often in American Depositary Receipt (ADR) or Global Depositary Receipt (GDR) form, or with the help of a local broker, may be practical vehicles.

Active management in emerging countries may take advantage of inefficiencies missed by a passive approach. Both top-down country analysis and bottom-up stock picking can be rewarding, but investors need to be very aware of high transaction costs. Given the volatility of individual countries, local prices can overreact in either direction to anticipated events. In 2006, in Brazil with Lula and in Russia with Putin, political events interpreted negatively by the markets were in fact major buying opportunities. Country volatility presents an opportunity for disciplined rebalancing of emerging countries within a basket, in a strategy that often beats a capitalization-weighted benchmark.

Style Investing

There may be a natural inclination for global investors to invest in the most successful companies in emerging markets, giving their portfolios a tilt toward growth styles. However, there is adequate information available to make at least broad cuts toward value and smaller capitalization investing. Figure 13.8 illustrates at a country-picking level the trade-off between price, expressed as price-to-book ratio, and profitability, expressed as return on equity.

Stock Picking

Understanding companies requires understanding the global industries in which they compete as well as the sometimes fierce competitors located in emerging countries. Investing in these emerging competitors need not mean stepping down in quality. The Indian software company Infosys, for example, does work at the frontier of technology and sets a world standard in terms of its financial disclosure. Its web site, www.infosys.com, is replete with full geographical and product line details that are too lacking from most companies in the developed world. The company loses nothing with this degree of openness, since competitors already find out what they need to know from insiders and former employees. However, the information turns security analysts into friends of the company rather than adversaries. Though it starts from a low base, this kind of openness is increasing in emerging markets because of demonstrated increases in value when global investors feel more comfortable (Gelos and Wei, 2005).

As earlier noted, this chapter is written from a practitioner's perspective. However, there is much to be gained from academic research. The following studies are starting points from which many other references may be found.

In an impressive thread of continuing study, Harvey (1995); Erb, Harvey, and Viskanta (1996); Bekaert, Erb, Harvey, and Viskanta (1998); Bekaert and Harvey (2000); Bekaert, Harvey, and Lumsdaine (2002); and Bekaert, Harvey, Lundblad, and Siegel (2007) document the growth of understanding of emerging market investment characteristics. Important insights have also been contributed by Gelos and Wei (2005) on the impact of greater transparency, and by Dvorak (2005) on the information advantages of local investors.

Investigating the basis for skepticism, we have Errunza, Hogan, and Hung (1999) on whether diversification can be achieved without trading abroad; Conover, Jensen, and Johnson (2002) on the need for timing investing in emerging markets; Stulz (2005) on the limits of globalization; and Chen, Bennett, and Zhang (2006) responding to assertions that globalization has made country analysis less interesting than analysis of industry sectors.

The history of development in today's emerging markets reveals a pattern of innovation diffusion that clearly has much further to go. During a long transition period, obstacles to open and market-based economic decision making, such as lack of information, resistance by special interest groups, and lack of resources for entrepreneurs, will continue to decline. Large populations in less developed countries will develop economies that are more productive and more open and reliable markets will leverage this productivity to create high asset values.

Many developed country investors still perceive emerging markets as being overpriced or, on the contrary, too ravaged by wars, disease, famine, and authoritarian governments to merit investment. We believe both these views represent deceptive stereotypes. Many emerging market countries have sound macroeconomic fundamentals.

Frequently, real per capita GDP is rising, inflation is low, currency exchange rates are becoming more stable, and corporate profits and return on investment are relatively high. From an economic standpoint, they are clearly emerging rather than stagnating. Looking ahead, they are likely to move on to become part of the developed world, and the stage is set to bring along a new set of emerging candidates from today's frontier markets. While available information is often sparse, local regulations are complex, and research coverage by analysts and brokerage firms is limited, these were also the characteristics of now successful emerging markets 20 years ago.

The remaining lacks of transparency and liquidity mean that security analysis and portfolio construction must be based on more care, diligence, and a longer-term perspective than investments in the developed markets. This opens opportunities for active investing styles that may be diminishing in more efficient developed capital markets. There are many risks in emerging markets, and setbacks are very apparent, but they can be reduced substantially through diversification.

As emerging markets develop further, the still enormous gap versus developed economies in terms of security value, GDP, and human capital will likely continue to shrink. Of course, as their equity markets become more efficient and populated by global investors, their return correlations with other markets are likely to continue to rise and the low valuations in overlooked segments will be harder to find. Consequently, the most attractive period for investment is in countries undergoing transition in expectations.

Bekaert, G., Erb, C., Harvey, C., and Viskanta, T. (1998). Distributional characteristics of emerging market returns and asset allocation. Journal of Portfolio Management 24, 3: 102–116.

Bekaert, G., and Harvey, C. (2000). Foreign speculators and emerging equity markets. Journal of Finance 55, 2: 565–613.

Bekaert, G., Harvey, C., and Lumsdaine, R. (2002). The dynamics of emerging market equity flows. Journal of International Money and Finance 21, 5: 295– 350.

Bekaert, G., Harvey, C., Lundblad, C., and Siegel, S. (2007). Global growth opportunities and market integration. Journal of Finance 62, 3: 1081–1137.

Chen, J., Bennett, A., and Zheng, T. (2006). Sector effects in developed vs. emerging markets. Financial Analysts Journal 62, 6: 40–51.

Conover, C., Jensen, G., and Johnson, R. (2002). Emerging markets: When are they worth it? Financial Analysts Journal 58, 2: 86–95.

Darroch, F. (2005). Case study: Lesotho puts international business in the dock. Global Corruption Report 2005. Transparency International.

de Soto, H. (2000). The Mystery of Capital, New York: Basic Books.

Dvorak, T. (2005). Do domestic investors have an information advantage? Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Finance 60, 2: 817–839.

Erb, C., Harvey, C., and Viskanta, T. (1996). Expected returns and volatility in 135 countries. Journal of Portfolio Management 22, 3: 46–58.

Errunza, V., Hogan, K., and Hung, M. (1999). Can the gains from international diversification be achieved without trading abroad? Journal of Finance 54, 6: 2075–2107.

Friedman, T. (2005). The World Is Flat: A Brief History of the Twenty-First Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Gelos, R., and Wei, S. (2005). Transparency and international portfolio holdings. Journal of Finance 60, 6: 2987–3020.

Harborn, L., Hogbladh S., and Wallensteen, P. (2006). Armed conflict and peace agreements. Journal of Peace Research 43, 5: 617–631.

Harvey, C. (1995). Predictable risks and returns in emerging markets. Review of Financial Studies 8: 773–816.

The Human Security Report (2005). Human Security Centre, University of British Colombia.

Merton, R. (1987). A simple model of capital market equilibrium with incomplete information. Journal of Finance 42, 3: 483–510.

Siegel, J. (2005). The Future for Investors: Why the Tried and True Triumph over the Bold and New. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Siegel, J. (2007). Stocks for the Long Run, 4th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Stulz, R. (2005). The limits of financial globalization. Journal of Finance 60, 4: 1595–1638.

World Population Prospects. (2004). Population Database, United Nations Population Division.

Wilcox, J. (1984). The P/B-ROE valuation model. Financial Analysts Journal 40, 1: 58–66.

World Development Indicators Online. (2005). The World Bank.