SHANI SHAMAH

Consultant, E J Consultants

Abstract: The foreign exchange market is by far the largest market in the world, and although the world's currency markets are generally thought of as the exclusive domain of the largest banks and multinational corporations, nothing could be further from the truth. Even though major currencies are traded like commodities, it is distinguished from both the commodity or equity markets by having no fixed base. In other words, the foreign exchange market exists through communications and information systems consisting of telephones, the Internet or other means of instant communications, for example, Reuters and Bloomberg. The foreign exchange market is not located in a building, nor is it limited by fixed trading hours, but is truly a 24-hour global trading system. It knows no barriers and trading activity in general moves with the sun from one major financial center to the next—so that around the clock a foreign exchange market is active somewhere in the world. Because of this decentralization, the total size of the foreign exchange market can only be guessed at. The foreign exchange market is an over-the-counter market where buyers and sellers conduct business. Many of the traders in the markets have all started with this simplest of products: just buy low and sell high, or sell high and buy low. Thus, the foreign exchange market is a global network of buyers and sellers of currencies with a foreign exchange transaction being a contract to exchange one currency for another currency at an agreed rate on an agreed date. Today, what began as a way of facilitating trade across country borders has grown into one of the most liquid, hectic, and volatile financial markets in the world—where banks (and many hedge funds) are the major players and have the potential of generating huge profits or losses.

Keywords: foreign exchange, spot rate, spot value, reciprocal rate, indirect terms, European terms, fixed currency, variable currency, American terms, bid, offer, spread, market maker, price taker, market user, big figure, direct dealing, brokered dealing, cross rates, price determinants, market/price risk, country risk, credit risk, dealing room, dealers, back office, two-way price, quote, pips, risk, hit, foreign exchange exposure

The foreign exchange (FX) market includes the cash market and the FX derivatives market. The focus in this chapter is on the cash market, which is more commonly referred to as the spot foreign exchange market.

A foreign exchange, or currency rate is simply the price of one country's money in terms of another's. Although exchange rates are affected by many factors, in the end, currency prices are a result of supply-and-demand forces. The world's currency markets can be viewed as a huge melting pot: In a large and ever-changing mix of current events, supply-and-demand factors are constantly shifting, and the price of one currency in relation to another shifts accordingly. No other market encompasses as much of what is going on in the world at any given time as foreign exchange.

Approximately 80% of foreign exchange transactions have a dollar leg. The dollar plays such a large role in the markets because:

It is used as an investment currency throughout the world.

It is a reserve currency held by many central banks.

It is a transaction currency in many international commodity markets.

Monetary bodies use it as an intervention currency for operations in their own currencies.

The most widely traded currency pairs are:

The American dollar against the Japanese yen (USD/ JPY)

The European euro against the American dollar (EUR/USD)

The British pound against the American dollar (GBP/ USD)

The American dollar against the Swiss franc (USD/ CHF)

In general, EUR/USD is by far the most traded currency pair and has captured approximately 30% of the global turnover. It is followed by USD/JPY with 20% and GBP/USD with 11%. Of course, most national currencies are represented in the foreign exchange market, in one form or another. Most currencies operate under floating exchange rate mechanisms against one another. The rates can rise or fall depending largely on economic, political, and military situations in given country.

The basic information and common definitions of foreign exchange and the foreign exchange market follow:

Foreign exchange market is a global network of buyers and sellers of currencies.

Foreign exchange or FX is the exchange of one currency for another.

Foreign exchange rate is the price of one currency expressed in terms of another currency.

Foreign exchange transaction is a contract to exchange one currency for another currency at an agreed rate on an agreed date.

Spot exchange rate is the ratio at which one currency is exchanged for another for settlement in two business days (value date)

So, what is the history of the foreign exchange market? Rather than start way back in history with the barter system and discuss when coins were first introduced, let's start with when the original method for exchange and payment of international debits and credits was to use gold. To do this, countries agreed not to restrict the cross-border flow of gold and to allow their gold coins to be melted down and recast by other countries. During this period, rate fluctuations and associated risks were small. The gold standard lasted until World War I. To finance the war, most countries printed large amounts of money—far in excess of their gold reserves—leading to the demise of the gold standard. Efforts to return to the gold standard failed after the war because most currencies were either over- or undervalued and were not easily matched to a gold standard. In addition, worldwide inflation at this time caused disparities among currencies, which led to currency devaluations and further inequalities among currencies. Needless to say, this was a very difficult time to exchange foreign currencies.

At the end of World War II, in an effort to avoid the difficulties encountered after World War I, the Americans proposed a system based on fixed exchange rates and the creation of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) at the Bretton Woods conference in 1944. The new system had three goals:

To create a system with stable exchange rates

To eliminate exchange controls

To allow convertibility of all currencies

To do this, the Americans guaranteed that it would buy and sell gold at $35 per ounce, thereby establishing the dollar as a parity reference for all currencies and gold. In other words, the dollar replaced gold as the dominant reserve currency of the international monetary system. As a result, in addition to reserves of gold, countries held reserves of dollars, which earned interest and were easily converted into gold. The dollar became the major currency for settlement of international transactions.

This system worked well until the late 1960s when, in spite of attempts made to stabilize the markets, the widely different growth rates in individual countries caused difficulties in the fixed rate system. Some countries revalued their currencies, while others let them "float." Eventually, this led to the demise of the Bretton Woods system. In 1973, due to continued loss of confidence in the American dollar and massive American balance of payments deficits, the system of fixed exchange rates finally collapsed. Because fixed rates were not practical, most countries let their currencies float against other currencies. This was seen as a short-term solution, until a return to stable, fixed rates was possible. However, the IMF conference in 1976 formally adopted the flexible exchange rates with a "gentlemen's agreement." Member nations are required to abstain from rate manipulation and from creating unfair advantages over other member nations.

The foreign exchange market is not entirely a free market because some countries have rules regarding repatriation of funds and some currencies are fixed or semifixed to other currencies. An example of the latter is the old European Monetary System (EMS), which was an exchange rate mechanism including most European Community (EC) countries where currencies fluctuated within relatively narrow, mutually agreed upon bands.

Since currencies have been able to float, their values have fluctuated dramatically. Continuous adjustments in currencies' values have brought volatility to the foreign exchange market. As a result, any company or institution doing business which involves currencies other than its own is faced with exposure to changes in the values of those other currencies.

By way of explanation, foreign exchange exposure is the risk of financial impact due to changes in foreign exchange rates and, in general, there are three types of foreign exchange exposures:

Transactions exposures principally impact a company's profit and loss and cash flow and result from transacting business in a currency or currencies different from the company's home currency.

Translation exposures principally impact a company's balance sheet and result from the translation of foreign assets and liabilities into the company's home currency for accounting purposes.

Economic exposures relate to a company's exposure to foreign markets and suppliers. More difficult to identify, economic exposure is sometimes also referred to as competitive, strategic, or operational exposure.

There are actually five basic foreign exchange products:

Spot transactions

Forward contracts

Foreign exchange futures contracts

Foreign exchange swaps

Currency options

The last four are referred to as foreign exchange derivative contracts.

The basic uses of foreign exchange products include the following:

For settlement and funding in order to convert cash from one currency into another for commercial transactions (e.g., import or export payables or receivables) or to convert capital flows (e.g. dividends, inter-company loans and investments)

To hedge/manage foreign exchange exposures caused by the passage of time and exchange rate fluctuations

For arbitrage to take advantage of short-term discrepancies between prices in different currencies or marketplaces

For investment to take advantage of changing exchange rates and interest rates and to optimize all components of a global investment strategy

To speculate so as to take advantage of anticipated exchange rate changes

In actual terms for spot transactions, client groups, such as corporations, investors, funds, and institutions, will use spot transactions as part of their foreign exchange management programs. Speculators will also use this market because it is an extremely active and liquid market with roughly two-thirds of all foreign exchange activity being traded. There can be plenty of movement (volatility) in any one day, which will enable a speculator to possibly benefit from such gyrations.

The foreign exchange market has some unique characteristics. As has already been mentioned, it is active 24 hours a day. Generally speaking, there is no centralized market place as there is with the stock market. Rather, deals are done in an "over-the-counter" style, with individual buyers and sellers dealing verbally, or acting through brokers; over the telephone or electronically over the Internet via various foreign exchange trading platforms.

This means that rates change from dealer to dealer rather than being controlled by a central market. For example, investors do not call around to get the best price on a specific stock because the price is quoted on the stock exchange, but they do call around to different dealers to get the best exchange rate on a specific currency. They may also refer to various widely available bank/broker screens (e.g., Bloomberg and Reuters) for indicative pricing only.

There are two exceptions to the lack of a physical marketplace. First, foreign currency futures are traded on a few regulated markets, of which the better known are the International Monetary Market (IMM) in Chicago, the SIMEX (Singapore International Monetary Exchange), and the LIFFE (London International Financial Futures Exchange) in London.

Second, in some countries there are daily "fixings" where major currency dealers meet to "fix" the exchange rate of their local currency against currencies of their major trading partners at a predetermined moment in the day. Immediately after the fixing, the rates continue to fluctuate and trade freely. The fixings happen less in this day and age and are only symbolic meetings and represent less than 0.5% of all worldwide daily trading.

Although there is no central marketplace, there are major dealing centers in three regions of the world where much of the world's FX transactions take place. There are also many smaller centers in different parts of the world.

The western European market is serviced by major dealing centers in London, Frankfurt, Paris, and Zurich. The North American market is serviced by the major dealing center in New York City, but there are also active dealing rooms in Chicago, San Francisco, Los Angeles, and a few other major cities in the States. The far eastern market is serviced by major dealing centers in Tokyo, Hong Kong, and Singapore. Around 84% of the world's foreign exchange business is executed in these major dealing centers.

To make a market means to be willing and ready to buy and sell currencies. Market makers are those market participants that both buy and sell currencies. According to market practice, a market maker, dealer, or trader will generally quote a two-way price to another market maker. (The terms dealer and trader are used interchangeably when referring to market makers.) For market makers, reciprocity is standard practice. They constantly make prices to one another, and market makers are primarily banks.

Price takers are those market participants seeking to either buy or sell currencies and are usually corporations, fund managers, or speculators. For price takers, there is no reciprocity inasmuch as they won't quote a price to other market participants.

The major participants in the market play a number of roles depending on their need for foreign exchange and the purpose of their activities:

International money center banks are market makers and deal with other market participants.

Regional banks deal with market makers to meet their own foreign exchange needs and those of their clients.

Central banks are in the market to handle foreign exchange transactions for their governments, for certain state-owned entities, and for other central banks. They also pay or receive currencies not usually held in reserves and stabilize markets through intervention.

Investment banks, like money center banks, can be market makers and deal with other market participants.

Corporations are generally price takers and usually enter into foreign exchange transactions for a specific purpose, such as to convert trade or capital flows or to hedge currency positions.

Brokers are the intermediaries or middlemen in the market, and as such do not take positions on their own behalf. They act as a mechanism for matching deals between market makers. Brokers provide market makers with a bid and/or offer quote left with them by other market makers. Brokers are bound by confidentiality not to reveal the name of one client to another until after the deal is done.

Investors are usually managers of large investment funds and are a major force in moving exchange rates today. They may engage in the market for hedging, investment, and/or speculation.

Regulatory authorities, while not actually participants in the market, impact the market from time to time. This sector includes government and international bodies. Most of the market is self-regulated, with guidelines of conduct being established by groups such as the Bank for International Settlement (BIS) and the IMF. National governments can and do impose controls on foreign exchange by legislation or market intervention through the central banks.

Speculators are growing in numbers by the day as access to the Internet becomes more freely available and with ease of access to various online trading platforms. It is said that 95% of the daily foreign exchange volume is made up of trading or speculation, while the remaining 5% of daily volume consists of governments and commercial activities.

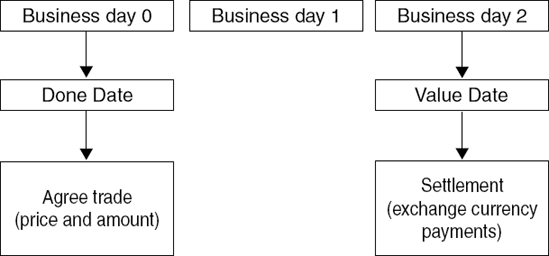

Foreign exchange rates are a means of expressing the value and worth of one economy as expressed by its currency as compared to that of another. Normal market usage is to quote the exchange rate for spot value, that is, for delivery two business days from the trade date (except Canadian transactions against the dollar, where the spot date is only one day). The two business days are normally required in order to get the trade information between the counterparties involved agreed and to process the funds through the local clearing systems. The two payments are made on the same date, regardless of the time zone difference.

Figure 64.1 provides an example of a foreign exchange transaction.

The rate used in a spot deal is the spot rate and is the price at which one currency can be bought or sold, expressed in terms of the other currency, for delivery on the spot value date. The spot exchange rate can be expressed in either currency; thus, this price has two parts, the base currency and the equivalent number of units of the other currency. For example, a rate for the U.S. dollar ($ or USD) against the Swiss franc (CHF) would be quoted as 1.2507 on July 25, 2006. (We will use exchange rates on this date throughout the chapter.) This means there are 1.2507 francs to $1. When one rate is known, the spot exchange rate expressed in the other currency (the reciprocal) is easily calculated. The price of $1, expressed in Swiss francs, is l/$0.7996 or CHF 1.2507.

Although some newspapers calculate and publish both exchange rates, it has become standard market practice among traders to quote foreign exchange for most currencies as the amount of foreign currency that will be exchanged for $1. For example, if a bank trader were asked to quote a rate for Swiss francs against the dollar, the response would most likely be CHF 1.2507 rather than $0.7996. In this case, $1 is the traded commodity and the trader is quoting the price in Swiss francs. This type of quotation is known as European terms.

It should be noted that the U.S. dollar is the most popularly traded currency because it is the primary currency for international trade and official reserves (although the Euro is rapidly catching the U.S. dollar as a reserve currency). Therefore, the most frequently quoted exchange rates and the most liquid markets are those between dollars and various foreign currencies.

Normally, the accepted practice is to quote in indirect or European terms. The price in dollar terms signifies how many dollars a single unit of the foreign currency is worth. In this case, the foreign currency is the fixed currency and the dollar is the variable currency.

However, there are exceptions to this rule. In contrast, the European euro, the British pound, Australian and New Zealand dollar, and some other old British area currencies, such as the Maltese pound, are quoted as the number of American dollars to the currency. This is an overhang from the days when these currencies were primarily quoted against sterling and therefore adopted the same quoting convention as sterling against the dollar. In this case, the currencies are always expressed in American or direct terms. For example, if a Swiss franc against the dollar price is expressed, it would read CHF 1.25/$1 or $1 equals CHF 1.25. This means that it costs CHF 1.25 to buy $1. The American dollar is the fixed currency and the Swiss franc is the variable currency. Alternatively, if a dollar against sterling price is expressed, it would read $1.84/£1 or £1 equals $1.84. This means that it costs $1.84 to buy £1. The pound is the fixed currency and the dollar is the variable currency.

Thus, the usage of either European terms or American terms is based on market practices. A market trader would quote pounds sterling as $1.8424 per pound and euro as $1.2598 per euro. This distinction is critical to understanding foreign exchange quotes and dealing screens. For example, when a corporate treasurer telephones a bank asking for foreign exchange quotes, the trader will assume the treasurer understands market conventions and will quickly rattle off prices for different currencies in the customary European or American terms.

Foreign currency traders are considered to be dealers when they make a two-way market price, that is, not just quoting one rate but two—that is, they provide both a bid price at which a trader is willing to buy a currency and an offer price at which a trader is willing to sell a currency. Examples of two-way quotes are:

EUR/USD | 1.2598—1.2601 |

USD/JPY | 117.06—117.09 |

USD/CHF | 1.2507—1.2510 |

It should be noted that, generally, most currencies run to four figures after the point (significant figures after the decimal point) but there are exceptions like the U.S. dollar against the Japanese yen, which, as can be seen, runs to only two.

Like other financial markets, the spread favors the dealer who buys currency at one price and sells it at a slightly higher price. To determine whether a trade will take place at the dealer's bid or offer rate, a client must first know which currency the dealer is bidding or offering, that is, whether the terms are quoted in European terms such that the traded currency is $1 or in American terms, such that the traded currency is one unit of foreign currency.

As with commodities and equities, foreign exchange has very specific ways of quotation and it is necessary to become familiar with these. Domestically, most countries use the direct quotation, and internationally, it is convention in the foreign exchange markets to quote most currencies against the dollar, with the dollar as the base currency. Using the dollar base simplifies currency trading and it will allow a trader to compare rates more easily.

If, for example, the dollar against the Swiss franc is quoted as 1.2507/10, what does this quote actually indicate? As has been mentioned, a market maker will normally quote a two-way price; in other words, they are obliged to make a bid and an offer for dollars against, in this case, the Swiss franc. Market makers will always quote to their advantage and to the other person's disadvantage. The left-hand side of the quote (1.2507) is the quoting person's bid for dollars, obviously surrendering as few Swiss francs as possible. Conversely, the right-hand side of the quote (1.2510) is the market maker's offer for dollars at which they will ask for as many Swiss francs as possible. The difference between the rate at which someone will buy a currency and the rate at which they will sell is called the profit (spread).

For example, when a market maker quotes spot Swiss franc (against the dollar), the trader will say: "dollar/Swiss franc is 1.2507—1.2510" where their bid is at CHF 1.2507/$1 and their offer is at CHF 1.2510/$1. That is, the market maker will buy $1. for CHF 1.2507, which means the client will sell $1 for CHF 1.2507—the client sells at the market maker's bid. Conversely, the market maker will sell $1 for CHF 1.2510, which means the client will buy $1 for CHF 1.2510—the client buys at the market maker's offer.

Figure 64.2 provides an example of a currency transaction.

It is important to remember that in any foreign exchange transaction, each party is both buying and selling, since it is buying one currency while selling another. One way of determining which is the buying rate and which is the selling rate is to remember that a market maker will buy dollars for another currency at a low rate (its bid rate) and sell dollars for another currency at a high rate (its offered rate). For currencies like sterling and euro, the market maker will buy sterling for dollars at the bid rate and sell sterling for dollars at the offered rate.

Usually market makers will quote only the last two numbers in the price, for example 06/09, thus assuming the other party knows the rest of the price, which is known as the big figure, in this case 117 (dollar/Japanese yen). In an example of, say EUR/USD, being quoted 1.2598—1.2601, the big figure is both 1.25 and 1.26. However, in this case, the trader would say: "98—01, around 1.26."

As mentioned earlier, by quoting a higher offer than bid, the market maker ensures that if both sides of the quote are dealt on simultaneously, the market maker will profit from the difference between the bid and offer. This difference is the spread, and the size of the spread is affected by various factors. The main factors are the assessment of risk, the volatility of the market, the liquidity of the currency, and the time of day in each time zone.

When a dealer calls another dealer for a price, it is called direct dealing. When a dealer puts a bid or offer in at a foreign exchange broker or via some Internet trading platforms, it is called brokered dealing. Brokered dealing is somewhat like a silent auction, as the buyers and sellers are unaware of each other's identity until the deal is done, and the bid and offer process may not be accepted.

A cross rate is the rate of exchange between two currencies that do not involve the domestic currency. In other words, within the international marketplace, cross rates have come to mean rates that do not involve the American dollar.

Most transactions are dealt as the American dollar against another currency. However, currencies are also dealt against each other, for example the Swiss franc against the Japanese yen (CHF/JPY). In these instances, it is necessary to calculate the cross rate. In order to calculate this cross rate, start with the two rates against the dollar. The objective is to obtain the number of Japanese yen per Swiss franc Consider:

One dollar | = | francs 1.2507/10 |

One dollar | = | yen 117.06/09 |

Each quotation represents a bid and an offer for the currency against the dollar. The cross rate is achieved by taking opposite sides of the two prices. The rate for selling yen and buying francs is achieved by using the left-hand side of the dollar/yen (bid) rate and the right-hand side of the dollar/franc (offer) rate. The same logic is applied for buying yen and selling francs. Thus, the preceding quotations can be broken down as follows:

| 117.06 ÷ 1.2510 = 93.57 |

| 117.09 ÷ 1.2507 = 93.62 |

Hence, the spot cross rate for Swiss francs against the Japanese yen is 93.57/62. The number of places after the decimal point is determined by the convention of the quoted currency (the variable currency). In this example, this is the yen, since we are looking for the number of yen per franc. It is usual to quote cross currency exchange rates using the "heavier" currency as the base, for example, the number of yen per franc.

There is, of course, a variation to the rule. For currencies like the euro and sterling, it is market practice to multiply the respective currencies against each other. For example, consider the following;

| One dollar = yen 117.06/09 |

| One pound = dollar 1.8424/29 |

Then the sterling against yen spot cross rate calculation will be:

Thus, it follows that one pound is equal to 215.67 or 215.79 yen. This is the only way it is expressed.

Exchange rates (or prices) in the foreign exchange market are driven by the laws of supply and demand. The supply and demand for specific currencies change given the amount of trade and investment being done in that currency. If there is a high demand for a currency its value increases. If there is a low demand, then its value decreases.

However, exchange rates are affected not only by supply and demand. The exchange rate will also be influenced by the economic, political, monetary, and social factors of the country involved and also by outside developments. Exchange rates can change quickly and significantly, reflecting the volatility in the market; and rates can also be moved by rumors and anticipated factors. Typically, currency rates can fluctuate from day to day due to small imbalances in supply and demand and to economic and political factors that affect the sentiment of market makers and investors.

Economic factors include economic policy, disseminated by government agencies and central banks, and economic conditions, generally revealed through economic reports. Economic policy comprises government fiscal policy (budget/spending practices) and monetary policy, that is, the means by which a government's central bank influences the supply and "cost" of money, which is reflected by the level of interest rates. Economic conditions include:

Government budget deficits or surpluses. The market usually reacts negatively to widening government budget deficits, and positively to narrowing budget deficits.

Balance of trade levels and trends. The trade flow among countries illustrates the demand for goods and services, which in turn indicates demand for a country's currency to conduct trade. Surpluses and deficits in the trade of goods and services reflect the competitiveness of a nation's economy. For example, trade deficits may have a negative impact on the currency.

Inflation levels and trends. Typically, a currency will lose value if there is a high level of inflation in the country or if inflation levels are perceived to be rising. This is because inflation erodes purchasing power, thus demand, for that particular currency.

Economic growth and health. Reports such as gross domestic product (GDP), employment levels, retail sales, inflation figures, and others, detail the levels of a country's economic growth and health. Generally, the more healthy and robust a country's economy, the better its currency will perform, and the more demand for it there will be.

Internal, regional, and international political conditions and events can have a profound effect on the currency markets. For instance, political upheaval and instability can have a negative impact on a nation's economy. The rise of a political faction that is perceived to be fiscally responsible can have the opposite effect. Also, events in one country in a region may spur positive or negative interest in a neighboring country and, in the process, affect its currency.

Market psychology is perhaps the most difficult to define but it does influence the foreign exchange market in a variety of ways:

Flight to quality. Unsettling international events can lead to a "flight to quality," with investors seeking a "safe haven." There will be a greater demand, thus a higher price, for currencies perceived as stronger over their relatively weaker counterparts.

Long-term trends. Very often, currency markets move in long, pronounced trends. Although currencies do not have an annual growing season like physical commodities, business cycles do make a difference. Cycle analysis looks at longer-term price trends that may arise from economic or political trends.

"Buy the rumor, sell the fact." This market truism can apply to many currency situations. It is the tendency for the price of a currency to reflect the impact of a particular action before it occurs and when the anticipated event comes to pass, react in exactly the opposite direction. This may also be referred to as a market being "oversold" or "overbought."

While economic numbers can certainly reflect economic policy, some reports and numbers take on a talisman-like effect. The number itself becomes important to market psychology and may have an immediate impact on short-term market moves. "What to watch" can change over time. In recent years, for example, money supply, employment data, trade balance figures, and inflation numbers have all taken turns in the spotlight.

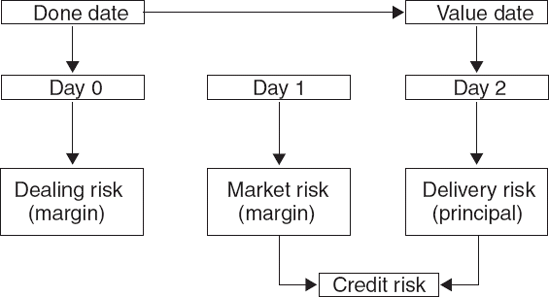

It must be remembered that there are risks with spot transactions. First, there is credit risk. Like the risk a bank incurs when making a loan, a foreign exchange contract poses the risk that the client will not perform according to the terms of the contract (that is, will not deliver the appropriate currency on time). In a foreign exchange transaction, the market maker and the client agree that each will deliver to the other a specified amount of a currency on a specific date, at an agreed rate. Trading the currencies of countries that are in different time zones compounds this risk.

Second, there is market/price risk. Trading in any currency has a degree of risk. Exchange rate risk is inevitable because currency values rise and fall constantly in response to market pressures. When engaging in a foreign exchange trade, the client's position is open until it is closed or covered. While that position is open, the client is exposed to the risk of changes in exchange rates. A few moments can transform a potentially profitable transaction into a loss.

Third, there is country risk. Some countries (and their currencies) are more risky than others. Country risk may be due to anything from governmental regulations and restrictions to political situations, or the amount of foreign currency reserves the country has. However, this risk is usually of less significance.

The spot exchange risk is shown graphically in Figure 64.3.

Today, dealings in the foreign exchange market are usually done over the telephone or via the Internet. The Internet is a very quick and easy way to transact a foreign exchange transaction, with "click and deal" or "request for price" systems dominating. However, the majority of all trading is still transacted over the telephone. Using the telephone allows for prompt and timely execution but does leave room for errors in communication.

When asking for a quote, the following basic information needs to be conveyed to the market maker directly or to a corporate foreign exchange dealer: type of transaction, currency pair, and quantity. For example, a client would say: "I want to buy CHF 5 million value spot—what is your quote, please?"

Today, a market maker normally quotes a two-way price, where the trader stands ready to bid for, or offer up to, some standard amount. The difference between the two prices, as already mentioned, is the spread. Market convention, where trading is between market "professionals," is not to quote the big figures. Instead, a trader tends to quote only the last two figures of the price, the pips. For example, if the rate of dollars against Swiss francs were 1.2507/10, then the trader would quote only 07/10. That is, the trader bids for dollars at 1.2507 and offers dollars at 1.2510. If a client is checking prices with other market makers, then the client should inform the trader by saying that it is at his risk, that is, the quote can be changed by the trader. The client should then ask again when a new price is needed. If the client wishes to deal, then the trader's price would be hit, that is, where one side of the price or the other is accepted. Written confirmation, whether the deal is oral or electronic, will be exchanged and instructions taken as to whether this trade is to be settled or not and the currency amounts are transferred into the designated accounts on the value date.

As an example, suppose XYZ Corporation, based in Japan, needs to raise dollars to pay for a delivery of machine parts from America. The treasurer gets in contact with his bank dealer to arrange to buy the dollars in the spot market. The treasurer's screens display indicative prices contributed by certain major banks. This gives the treasurer a good idea of the current exchange rate. However, this is only an indicative rate and it is not a dealable price (that is, not a price to be dealt on). Therefore, the following steps are taken:

Treasurer: | Please quote me dollar/yen in 10 million dollars (at this stage there is no mention of whether the client wants to buy or sell dollars). |

Dealer: | 06/09. |

Treasurer: | I buy 10 million dollars. |

Dealer: | To confirm, you buy 10 million dollars against yen at 117.09 value spot. |

At this stage, the dealer fills in a deal ticket with the details of the trade including currencies, amount, which currency is bought and which one is sold, value date, exchange rate, counterparty, and settlement details if known.

The treasurer could also have said "at 09" or "mine."All three ways would be correct and within market practice. Also, the dealer knew that the treasurer was used to market conventions and, hence, did not quote the big figure of 117.

As another example, suppose that Mr. Jones is a high-net-worth individual who has a margin account with ABC International. He calls up and speaks to his favorite salesperson. After the customary pleasantries, Mr. Jones asks for a dealing price for sterling in "half a pound." The salesperson obtains the price from the trader and communicates it to Mr. Jones for consideration. It is likely that Mr. Jones has a general idea of where the price is from his computer screen. If Mr. Jones accepts the price, the salesperson immediately informs the trader, possibly via a hand signal. It is then up to the trader what happens with that position. The dealing conversation could be:

Mr. Jones: | A dealing price for half a pound, please. |

Corporate dealer: | Sure, price for half a pound coming— Charlie (trader), cable in half? |

Charlie: | Who for? |

Corporate dealer: | Old Mr. Jones. |

Charlie: | What's he doing? |

Corporate dealer: | How do I know—just give me the price. |

Charlie: | 20/30. |

Corporate dealer: | Cable in half a pound is 1.8420/30. |

Mr. Jones: | Hmm, I was hoping for a better spread. |

Corporate dealer: | Your risk, let me try for you, you know it is only in half a pound but let me ask. |

Charlie: | What's he doing—trading or not? |

Corporate dealer: | He is looking for a better spread. |

Charlie: | What, in half a pound? You decide—he is your client. |

Corporate dealer: | I am 1.84.23/28 now. |

Mr. Jones: | Hmmm... well... |

Corporate dealer: | Mr. Jones, your risk again. |

Mr. Jones: | Okay how now, please? |

Corporate dealer: | Charlie—how are you left on that half pound for Mr. Jones? |

Charlie: | Has he still not dealt—do what you like within 20/30 and let me know this side of Christmas. |

Corporate dealer: | 1.8424/29. |

Mr. Jones: | Okay I sell. |

Corporate dealer: | Okay to confirm you sell half a million pounds and buy dollars at 1.8424 for value spot. |

Mr. Jones: | Agreed and thanks. |

In the two preceding examples, the process happened in only one or two seconds, as the market can move very rapidly. The salesperson and the trader can always change the price as long as the client has not firmly accepted the last quote made. Before making a decision to actually trade, it is not unusual for a client to shop around for quotes from various market makers in order to obtain the best deal. Sometimes, clients will ask for quotes knowing that they are not ready to actually trade but just want to check where the market is.

It should be noted that the following information is needed when asking for a quote:

The two currencies being traded (e.g., $/JPY)

The value date of the trade (e.g., spot)

The amount (e.g., $1 million)

If possible, the trader will try to know what side of the price you are or, at best, guess. However, wherever possible, always ask for a two-way quote. But, in all cases, be extremely clear in the details of a trade or the instructions given, in order to avoid costly errors at a later stage. It is all too easy to mishear a quote "for a half" and think it is a quote in "four and a half."

In days gone by, banking institutions were the sole purveyor of the information vital to the transaction of business in the market. With no central organized market, bank dealers executed trades solely by telephone or telex, writing trade details on pieces of paper, keeping positions on blotters, and maintaining charts by hand. The resulting scarcity of information meant that price discovery was inefficient, bid-offer spreads were wide, margins were large, and major institutions played the largest role simply because they knew where activity and prices in the marketplace were occurring. As a result, foreign exchange trading was a profitable activity for these institutions. The risks of trading were somewhat controlled and isolated at the bank level, with a degree of volatility sufficient enough to warrant active participation by only the most sophisticated of market participants.

Today, most clients are pretty sophisticated when it comes to knowing where the market is and what bid-offer spreads to expect for the foreign exchange deals. Banks and brokers that are uncompetitive in their pricing don't even leave the starting blocks in the race to win foreign exchange business. What distinguishes the best from the rest is the provision of high-quality information, in the way of charting and flows of relevant market information. Also, clients are looking for systems that are Internet enabled, scalable across regions, reliable, and safeguarded against crashes. In addition, clients are looking for Internet platforms that offer real-time risk management systems, among other demands.

Today, access to price information is widely available. Both institutional investors and retail investors can now gain live access to multicontributor price feeds, which can be downloaded directly into spreadsheets, if necessary. In addition, up-to-the-minute political and economic developments are widely available through news sources such as MMS and CNBC. As a result of these developments, however, bid-offer spreads have collapsed, as have profit margins, and this in turn has hampered the growth of direct investor participation.

Also, any currency trader needs to develop a global perspective and a feel for intermarket relationships. Interest rate trends are the most important external information source. If the U.S. Federal Reserve cuts rates, the dollar should weaken. However, if the European Central Bank is expected to follow suit, interest rate trends will converge and the value of the currency may not change at all. A trader will need to follow not only the chairman of the Federal Reserve, but also his counterparts in the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan as well.

Currencies tend to be trendier than either stocks or commodities, and it is important to understand the trend from both a fundamental and a technical point of view. Currencies cannot reverse trends very easily because economies do not reverse quickly relative to one another. However, a successful trader will recognize how fundamentals and technicals combine to indicate a trend reversal. Of course, finding the trend reversal before it happens is the "Holy Grail" of trading. No one can be expected to be successful 100 percent of the time.

Activity in the foreign exchange market still remains predominantly the domain of the large professional players. Foreign exchange is both a science and an art. Risk can be quantified and alternatives identified to reduce or eliminate it. But judgment and personal attitudes toward risk, as well as other personal and corporate orientations, are required for consistent position management. However, with liquidity and the advent of Internet trading, plus the availability of margin trading, this 24-hour market is accessible to any person with the relevant knowledge and experience. Nevertheless, a strong, disciplined approach to trading must be followed, as profit opportunities and potential loss are equal and opposite.

De Grauwe, P. and Grimaldi, M. (2006). The Exchange Rate in a Behavioral Finance Framework. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Lyons, R. K. (2006). The Microstructure Approach to Exchange Rates. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rosenberg, M. (2003). Exchange Rate Determination. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Samo, L. and Taylor, J.P (2002). The Economics of Exchange Rates. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

Shamah, S. (2003). A Foreign Exchange Primer. London: Wiley Finance.

Taylor, F. (1997). Mastering Foreign Exchange and Currency Options. Upper Saddle River, NJ. Prentice Hall.

Weisweiller, R. (1990). How the Foreign Exchange Market Works. New York: New York Institute of Finance.