R. PHILIP GILES, PhD

Adjunct Professor of Finance and Economics, Columbia University Graduate School of Business and President, CBT Worldwide, Inc.

Abstract: After a 50-year hiatus, the American banking system is currently evolving from one characterized by severe geographic and product limitations into one with nationwide branching with banks offering a virtually complete array of financial services. This transformation was ushered in by a 10-year period of extensive deregulation at the state and federal levels, caused by a variety of external and technological factors. But although the banking system has been transformed, the complex web of overlapping banking regulatory authorities has not. Over the past two decades there has been substantial consolidation in the number of banking charters—with the number of banks falling by over half. However, we expect the dual banking system to survive, with a large number of individual banks compared to any other country in the world. One unanswered question at this time is whether the historic depository-nonfinancial business separation will continue.

Keywords: American banking system, structural transformation, post-Depression banking system, global banking constants, depository institutions, private bank, private banking, depository-nonfinancial separation, industrial loan companies, regulatory authorities, payments system, dual banking, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), Federal Reserve System, member bank, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), bank holding companies, board of governors of the Federal Reserve System (BGFRS), reserve requirements, relationships banking, disintermediation, money market mutual funds (MMMFs), bank failures, deregulation and reregulation, risk-based capital standards, off-balance-sheet (OBS) activities, technological progress, federal preemption, banking consolidation, nationwide branching, diseconomies of distance, universal banking

While the American banking system is unique to the world, it is neither emulated nor admired. This statement accurately describes the relationship of bank system differences between the United States and the rest of the world from colonial times until the present.

Although the Great Depression of the 1930s created unprecedented turbulence to the U.S. banking system, it was remarkably stable for the next 50 years. Giles (1983) details the structure of the banking system on the brink of change. Over the past two decades the American banking system has undergone tremendous structural transformation, moving closer to that found in other developed nations. According to Berger, Kashyap, and Scalise (1995) the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s were the most turbulent period for U.S. banking since the Great Depression. And, although structural change is still in progress, the ultimate form of the future banking system in the United States can be envisioned with some degree of certainty.

This chapter is organized into four parts. The first section describes the post-Depression banking system, including the regulatory structure, allowable bank products, and the scope and variety of banking organizations. This is followed by a description of the factors transforming the system into its current (evolving) form. The next section describes today's banking system and the last section summarizes the current structure and trends.

The banking system is a vital part of any economy. In brief:

Banks pool and absorb risks for depositors and provide investment and working capital for nonfinancial industries.

Banks are a particularly important source of funds for small borrowers.

With the central bank's discount window, banks provide a backup source of liquidity for any sector in temporary difficulty.

The central bank transmits monetary policy through banks.

Banks provide the payment media.

The combination of a fractional reserve banking system and banks' role in providing the payments media means that problems in the banking sector can propel the entire economic system into a tailspin. This is due to the fact that in times of economic stress, currency can be hoarded (that is, kept under the mattress or buried in the backyard), causing large contractions in the money supply.

For this reason all banks are heavily regulated and deposit insurance is often provided to protect small depositors who are the heaviest users of currency. And, due to heavy regulation, we find there is extensive data on the banking system facilitating comprehensive research in the industry.

Despite the differences among banking systems, there are some universal truths to be found between large and small banks in a given country and among banking systems in a wide array of national economies. These constants are due to the universal needs of the general public:

A safe place to store liquid wealth.

A convenient means of making day-to-day payments.

A source of credit.

There are global balance sheet constants which are listed below.

Bank assets can be placed into four slots, listed in decreasing level of liquidity:

Cash

Securities

Loans

Fixed assets

Two types of liabilities are found for any bank, with a third one for large banks in developed markets:

Core deposits—small saving and time deposits and checking deposits of customers.

Purchased funds—large negotiable CDs and interbank borrowing (for large banks in developed economies).

Capital—including common equity plus other potential items.

In the United States as well as the rest of the world, most bank assets are expressed at book value in contrast to market value as found in securities firms and investment management companies. However as banks evolve from the "buy-and-hold" policy to more asset trading, the proportion of bank assets valued at the market has increased and this trend will continue.

For American banks, the loan-to-asset ratio is typically around 60%, while Asian banks usually have 70%. For any bank, fixed assets are usually around 1% of total assets. Finally, equity is usually between 5% and 10% of total assets.

From the above we can draw the following conclusions about banks around the world:

Financial assets typically comprise 99% of total assets.

Equity does not serve as a funding source, but plays the role of loss absorption.

In this chapter the term "banking" refers to depository institutions. There are three major types of depositories:

Commercial banks.

"Thrifts," which comprise savings and loan associations and savings banks.

Credit unions.

A fourth category, state-chartered industrial loan companies (ILCs), have, until recently, played a niche role in the financial system.

Although the U.S. banking system is converging to structures found elsewhere, some unique features are likely to remain. The following paragraphs point out these anomalies.

The Separation of Depositories from Nonfinancial Businesses

Today, virtually all U.S. depository institutions are chartered by a government authority. In the past it was possible to accept deposits as a "private bank," which is an unincorporated firm without a charter that accepts deposits, but as Spong (2000) points out, it is no longer possible to establish a new depository without a charter. Furthermore, the number of private banks has declined over the past decades so that few remain at this time. The most prominent remaining private bank in the United States is Brown Brothers Harriman & Co. in New York.

The term "private bank" should be differentiated from the function of "private banking" which involves managing the assets of high-net-worth clients. Many chartered banks have "private banking" departments, while overseas banking centers such as Geneva and Zurich have a number of prominent private banks that play a significant role in global private banking.

Historically, in the United States there has always been a separation between depositories and nonfinancial firms but it is unclear at this time if this separation will continue in the future. In the past the main exception to this separation has been the previously mentioned industrial loan companies which can be owned by nonfinancial firms.

Bank Charters and Regulatory Authorities

We will see that the U.S. regulatory structure is complex with many overlapping authorities. The following paragraphs detail the evolution of the U.S. regulatory system, emphasizing that structural change usually occurs only after an economic crisis. Table 3.1 presents a comprehensive list of relevant federal banking legislation (see www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/important/index.htm).

Prior to the Civil War, the federal government had virtually no role in banking. Thus, two types of banks existed—state-chartered and private banks. The safety and quality of the banking system depended upon the level and enforcement of banking regulations. With bank regulation only at the state level, the quality of regulation varied widely. Because the predominant form of payment was specie and representative paper money, the quality of the payments system was poor. This presented a major deterrent to development of business relationships outside of the local area.

The economic crisis caused by the Civil War provided an opportunity to change the system. The National Bank Act of 1863 authorized federal chartering of depositories. This created the concept of "dual banking" for commercial banks. Today, dual banking exists for all major types of depository sectors listed earlier (except ILCs, which are only state-chartered), resulting in state and national banks, thrifts, and credit unions.

Table 3.1. Summary of Major Federal Banking Legislation

Year | Name | General Provisions |

|---|---|---|

1863 | National Bank | Act Established national banks; Created the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC); prohibited state banks from issuing currency |

1913 | Federal Reserve Act | Created the Federal Reserve System |

1927 | McFadden Act | Forced national banks to conform to branching laws of home state |

1933 | Glass-Steagall | Act Created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; separated investment banking from commercial banking; placed interest rate ceilings on bank deposits |

1956 | Bank Holding Company Act | Defined a bank as any institution that simultaneously accepts demand deposits and offers commercial loans; extended Federal Reserve supervision to any company that controls two or more banks; prohibited BHCs from purchasing a bank in another state; nonbank business must be "closely-related to banking" |

1970 | Douglas Amendment to the Bank Holding Company Act | Gave the Federal Reserve System authority over formation and activities of one-bank holding companies |

1978 | International Banking Act | Brought foreign banks in the U.S. under federal regulatory framework; required deposit insurance for branches of foreign banks accepting retail deposits in the United States |

1980 | Depository Institution Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 (DIDMCA) | Lowered and unified reserve requirements; required all depositories offering transactions accounts to maintain reserves with the Fed; phased out interest rate ceilings on bank deposits; raised FDIC insurance ceiling from $40,000 to $100,000; opened the Fed's discount window to all chartered depositories |

1994 | Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act (RNIBBEA) | Permitted bank holding companies to purchase banks in any state, subject to concentration limits; allowed interstate mergers between banks, subject to concentration limits and state laws |

1999 | Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act | Securities firms and insurance companies allowed to purchase banks; banks allowed to underwrite insurance and securities and engage in real estate activities; allowed the creation of financial holding companies (FHCs) with wider array of activities than allowed for bank holding companies |

Although the writers of the National Bank Act would have preferred to transfer all bank regulatory and chartering authority to the federal government, it was not possible. Thus, to this day each of the 50 states maintains a state banking department that charters and regulates state-chartered banks. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) is responsible for chartering and regulating national banks.

The economic crisis caused by the Panic of 1908 demonstrated the necessity of a lender of last resort, resulting in the passage of the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. While all national banks were required to be members, membership was not mandatory for state-chartered banks and most state banks chose to be nonmembers. The term "member bank" originally meant that a bank belonging to the Federal Reserve was entitled to all Fed services, including the discount window, but was also subject to all Fed regulations, including reserve requirements. This resulted in three types of chartered commercial banks—national member banks, state member banks, and state nonmem-ber banks.

The Great Depression began after the stock market crash of 1929 and in the next four years the United States lost over half of all banks through failure, mainly caused by currency drains by depositors (recall that a majority of banks were state nonmembers without discount window access). This banking panic demonstrated the need for deposit insurance. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was formed as part of the Glass-Steagall Act of 1933. Again, universal coverage was not mandatory, although all member banks were required to have insurance. This created a fourth banking sector, state-chartered nonmember, uninsured bank. However, over time, deposit insurance has come to be viewed as an economic requirement, so that the few uninsured banks in the United States as of 2006 hold less than 0.2% of total deposits.

As of the end of 2006, about 65% of all banks were state-chartered, nonmember banks and about 25% of all banks had a national charter. However, national banks controlled about 65% of all banking assets while state nonmember banks comprised about 20% of the total.

Due to severe geographic and product restrictions, banks began to reorganize, forming bank holding companies (BHCs). A one-bank holding company (OBHC) allows banking organizations to own separate subsidiaries that offer services beyond that allowed for banks and outside of the single bank's market area. Multibank holding companies (MBHCs) provide a means for a given banking organization to operate outside the geographic area allowed for a single bank. The Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 gave the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (BGFRS) the authority to regulate the nonbank-ing operations of bank holding companies (BHCs), and financial holding companies (FHCs) which are described below. Note that because ILCs did not offer demand deposit accounts, they did not fit the definition of "bank" in the BHC Act and thus escaped BGFRS oversight.

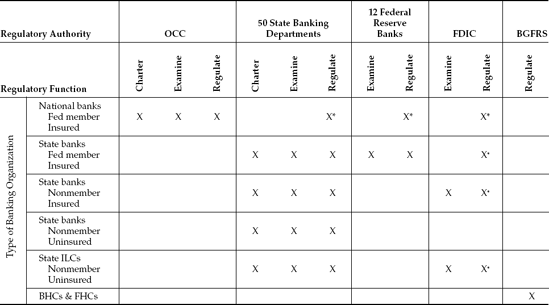

Table 3.2 presents the types of commercial banking organizations and the regulatory authorities to which they are subject. In this table, "X" under the regulation columns indicates primary regulatory authority, while the "X *" denotes secondary authority. Note that in addition to the examining staff of each of the 50 states, both the OCC and the Federal Reserve maintain a nationwide staff of examiners. Kohn (2004) points out that the quality of federal examination and supervision seems to vary noting that banks the Fed examines had the lowest failure rate, while the banks that OCC examined had the highest failure rate.

Originally, state regulations on allowable bank activities varied widely among the states, with some states allowing universal banking. But the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act forced the separation between banking and most securities activities so that banks were thereafter mostly confined to deposit acceptance and credit extension. Exceptions allowed bank dealing in all government bonds and underwriting of general obligation local government bonds. While brokerage activities were not specifically disallowed, discount brokerage was deemed to be less likely to be challenged, because no investment advice was offered.

When banks attempted to circumvent these restrictions through the bank holding company, the Bank Holding Company Act limited the products of their nonbanking subsidiaries to areas "closely related to banking." Thus, from 1933 until the mid-1980s there was almost a complete separation between the banking and securities industries.

The most unique aspect of American banking is the vast number of separately chartered depositories—banks, thrifts, and credit unions. Because the U.S. banking system was initially under individual state control, banks in a given state, as well as the state's banking authority, sought to protect their local markets from "foreign" banks, that is, any bank originating outside of the given state. Thus, all forms of interstate banking were prohibited.

The intrastate branching environments that existed until recently are listed below with the number of states as of 1975 given in parentheses, as detailed by Jayaratne and Strahan (1997).

Statewide branching (14).

Limited branching, usually within a county or metropolitan area (24).

Unit banking, that is, no branching (12).

Although in the distant past bank customers would be content to conduct all of their banking business at a single physical branch, increased mobility created a need for geographic expansion of a given banking organization. With limited or no branching permitted, a new bank location often required a separately chartered bank. This led to the proliferation in the number of banks.

While state restrictions could only be applied to state-chartered banks, the 1927 McFadden Act placed national banks under the same geographic rules as that of the bank's home state. At its peak in the 1920s the United States had over 31,000 separately chartered banks. By 1933 this number had fallen to a little over 14,000 and remained remarkably stable for the next 60 years, peaking at 14,500 in 1984. (It is interesting to note that Texas, a unit-banking state, had almost 2,000 separately chartered banks in 1986.)

Geographic restraints created a large number of small, undiversified banks. Calomiris (2000, Chapter 1) demonstrates that the system was vulnerable to bank runs and portfolio shocks while Jayaratne and Strahan (1997) illustrate the system was also plagued with high costs due to inefficiencies.

When banks attempted to circumvent interstate banking limits by establishing multibank holding companies, Congress passed the Douglas Amendment to the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 which gave the target state the authority to deny entry and this denial was universal.

One of the most unenlightened features of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act placed interest rate limits on bank deposits. No interest was allowed on consumer and business checking accounts while "Regulation Q" limited the amount of interest that could be paid on small time and savings deposits as well as large time and certificates of deposit.

Initially, with a weak economy and no inflation these ceilings were not binding. But by the 1960s with accelerating economic growth and rising inflation, market interest rates exceeded rates that banks were allowed to pay.

Partial deregulation was required in the mid-1970s. Penn Central Railroad failed and defaulted on its commercial paper (CP) obligations causing the CP market to lock up. This meant that issuers were unable to roll over maturing obligations, but banks could not issue large certificates of deposits (CDs) when their maximum rate was below the market. Thus, interest rate ceilings on large CDs were eliminated.

Reserve requirements force a bank to maintain a certain level of assets as a proportion of reservable liabilities. Originally, each state maintained separate reserve requirements. After 1914 the Fed had its own reserve requirements which were usually higher than that of the states. This was the reason a majority of state chartered banks chose to be nonmembers.

Originally, the Fed's reserve requirements were applied to most deposit liabilities including retail savings and time deposits, wholesale time deposits and all demand deposits, with the latter increasing with bank size. The highest reserve requirement exceeded 16% for checking accounts at large banks.

For all domestic time deposits, for example, large bank CDs, a bank faced three costs—the interest rate (iCD), reserve requirements (RRCD), and the FDIC insurance fee (CFDIC). However, the FDIC only insured domestic deposits and reserve requirements could not be imposed on balances held out of the United States, such as Eurodollar deposits. A given bank's cost of accepting time deposits within the United States exceeded the cost of a virtually identical dollar-denominated deposits accepted in a foreign branch. The total cost of a domestic time deposit rate was labeled the "effective domestic cost" or "EDC" which was computed as EDC = (iCD + CFDIC)/(1 — RRCD). With LIBID representing the bid rate on Eurodollar deposits, any bank accepting time deposits both in the U.S. and London would be no worse off in London as long as LIBID ≤ EDC. In an environment with high interest rates the domestic regulatory burden substantially widened the spread between LIBID and domestic CD rates, reaching a peak of 269 basis points in September 1971. Because of this, and the natural reluctance of many dollar holders to avoid potential U.S. control over their deposits, the Eurodollar market grew rapidly at the expense of U.S. banking business and jobs.

Banks rely on external data from bond rating agencies for credit extension and loan pricing decisions for large borrowers. This is referred to as the "hard data" approach. There is a national market for large corporate loans and lending rates are very competitive.

As Fields, Fraser, Berry, and Byers (2006) point out, banks maintain a personal relationship with consumers and small and medium-sized business for their credit decisions. This information, called "soft data," is not made public. With the need for face-to-face communication, this is typically viewed as a local market.

Starting in the 1980s many factors converged to substantially transform the U.S. banking system to a form more in line with that of other nations. Loss of market share due to increased external competition, increased volatility, and failure rates coupled with technological change led to substantial regulatory reform. Berger, Kashyap, and Scalise (1995) provide a comprehensive discussion of the early stages of this structural transformation.

Banks lost dominance on both sides of their balance sheet to other firms. The following paragraphs describe these developments.

Disintermediation

Originally, banks provided the main source of borrowed funds for consumers, a major source of funds for small and middle-sized enterprises and working capital funds for large firms. However, external competitors provided an increasing slice of funds to each of these borrowing classes.

In the corporate sector after 1960 the commercial paper market began to replace banks in providing short-term funds for large highly regarded firms. With the development of the original-issue high-yield bond market, banks also began losing market share to middle market and lower-rated large firms.

From flow-of-funds data for the nonfarm-nonfinancial sector the combination of bank loans, commercial paper, and corporate bonds has traditionally comprised 40% to 50% of total liabilities. And, until 1985 the bank loan portion of these three sources ranged between 30% and 40%, reaching a peak of 42% in 1984. However, it now totals around 17% of these three sources, less than half of the historical share.

Banks traditionally provided consumers the main source of nonmortgage credit, but credit cards began to supplant bank loans from about 1975 on. In 1974, credit cards provided about 10% of the total while today this source provides over 50%.

Deposits as a Source of Funds

In 1960 the average American bank received 90% of total funds from deposits, with 55% comprised of consumer and business checking accounts paying no interest and the other accounts under Reg Q ceilings. This cheap and stable source of funds has fallen dramatically over the decades for a variety of reasons.

As consumers switched from currency and checks to credit cards for their daily purchases, their checking account balances fell accordingly. Similarly, with noncom-petitive interest rate ceilings in a high inflation environment money market rates greatly exceeded maximum rates allowed by banks on consumer deposits.

Money market mutual funds (MMMFs) were first created in 1972. Assets consisted of Treasury bills, commercial paper, and large bank CDs with most of this yield passed on to shareholders. Because MMMFs give shareholders limited check writing abilities, banks lost market share. Today, the average bank receives less than 10% of its total funds from wholesale and retail checking accounts.

The banking structure that prevailed in the decade of the 1960s and 1970s became increasingly risky. With restricted branching, bank loan portfolios were undiver-sified geographically and by industry. Furthermore, as Berger, Kashyap, and Scalise (1995) point out, capital regulation was mainly ad hoc, did not differentiate by asset risk and did not include off-balance sheet activities. Over the 40-year span from the late 1960s to the present, the composite equity-asset ratio of American banks reached a low point of under 6% between 1978 and 1982.

With the twin bouts of inflation in the 1970s, extreme market volatility brought on bank stress and failures not seen since the Great Depression. Commodity and raw material prices rose sharply in the late 1970s, but, with a change in monetary policy in August 1979, inflation fell rapidly, carrying commodity prices down as well. This fall in prices was devastating for the agriculture and energy sectors as well as emerging market exporters.

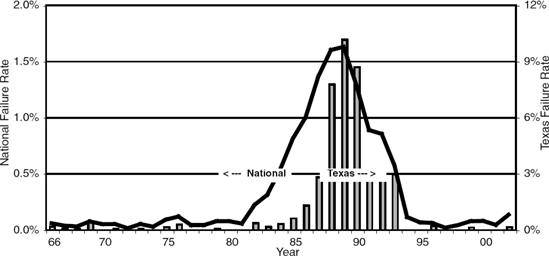

Between 1966 and 2002, the national failure rate for all banks averaged 0.3%. But during the 1982 to 1993 period the national failure rate tripled to an average of 0.9%, peaking at 1.6% during 1988 and 1989.

As bad as that sounds, it was much worse for Texas banks with energy, agriculture, and Latin American emerging market loans. Over the 1966 to 2002 period the Texas failure rate was four times the national rate at 1.2%, rising to 3.4% for the 1982 to 1993 period with a peak of 134 bank failures or 10.2% in 1989. As a means of reducing the cost of paying off the depositors of the insured depositors out-of-state MBHCs were allowed to buy failed Texas banks. Figure 3.1 presents the national and Texas failure rates between 1966 and 2006 illustrating the developing crisis of the late 1980s.

Regulatory and technological developments have substantially changed the banking system described above.

The movement from rigid regulation to recognition of market forces began with the gradual relaxing of rules on bank deposits.

Reserve Requirements

Partly due to the loss of dollar-based corporate banking business to offshore centers and the loss of retail bank deposits to MMMFs, the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (DIDMCA) was passed in 1980 and gradually reduced reserve requirements. By 1990, all reserve requirements were removed from retail and wholesale time and savings deposits and the reserve requirement for checking deposits was reduced to a flat 10%.

One result of this was to lower the domestic cost of large bank CDs so that since the mid 1990s rates on large domestic CDs, commercial paper, and LIBID trade within about 5 basis points.

Interest Rate Ceilings

The 1980 DIDMCA also removed interest rate ceilings from all savings and time deposits. And it allowed banks to offer interest-bearing checking accounts to consumers, giving them the ability to compete directly with MMMFs if they choose to do so.

At the height of the post-Depression bank failure rate, the U.S. bank regulators met with their counterparts from the Group of Ten at the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), located in Basel, Switzerland, to design an international, risk-based capital system, now termed "Basel I."

To avoid regulatory arbitrage, the central banks of each participating country agreed to enforce the new standards on all of their "internationally active" banks. This standard is applied to all U.S. banks as well as BHCs.

Risk-Adjusted Assets

All assets are placed in one of four "buckets" depending on risk with different levels of capital required for each bucket. These buckets are presented in Table 3.3.

Off-Balance-Sheet Activities

Due to the lack of capital requirements and the development of derivative products, large banks began to derive an increasing amount of revenue from off-balance-sheet (OBS) activities in the form of fee income. As Berger, Kashyap, and Scalise (1995) point out, the ratio of noninterest income to total income for all U.S. banks rose from 7.0% in 1979 to 20.9% by 1994. Furthermore, from FDIC data we find this ratio in late 2006 is 29.0% for all banks.

Table 3.3. Risk Weights for Credit Exposures under Basel I

Bucket | Allowable Assets | Risk Weight |

|---|---|---|

Riskless | Central government securities of OECD countries | 0% |

Cash and central bank deposits | ||

Money market risk | Local government bonds Deposits due from OECD banks | 20% |

Moderate risk | Residential mortgages Equivalent assets of interest rate swaps | 50% |

Standard risk | All other tangible assets | 100% |

A two-step process was defined in Basel I to account for OBS activity risks. Each activity is converted into an "equivalent asset" or "credit equivalent" by a "credit conversion factor." These factors are described in Table 3.4. Each credit equivalent is then placed into one of the four asset buckets described in Table 3.3.

Several points should be noted regarding Basel I. First, market risk is not addressed, only credit risk. This can be illustrated by noting that only options bought by the bank are covered, not options written by the bank. Note also that credit conversion factors are independent of the client. Thus, if a bank holds OBS products with an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) central government, the risk weight would be 0%.

Uniform Definition of Capital

Capital was defined uniformly for all banks and was divided into two layers or "tiers." The minimum capital ratio for Tier 1 is 4% and the minimum total capital level for Tier 1 and Tier 2 is 8% of risk-adjusted assets.

The first tier consists of common equity and perpetual preferred stock without cumulative dividends, less intangible assets such as goodwill which cannot be liquidated to repay depositors. Tier 2 mainly consists of subordinated debt, other preferred stock, and a portion of a bank's reserve for loan losses.

Table 3.4. OBS Credit Conversion Factors

Credit Products | |

|---|---|

Commercial L/Cs | 20% |

Loan commitments | 50% |

Performance bonds | 50% |

Financial guarantees | 100% |

FX Risk Products | |

|---|---|

Forward contracts | 5% |

Currency swaps | 5% |

FX options bought by bank | 5% |

Interest Rate Risk Products | |

|---|---|

Interest rate swaps | 0.50% |

Forward rate agreements | 0.50% |

IR options bought by the bank | 0.50% |

Common equity is the most important part of capital since it has all desirable properties of capital, namely:

Long-term stable funding, because equity is perpetual.

Loss absorption, because common equity protects all other funds providers.

Incentive for good management, since shareholders have voting rights.

As a result of Basel I, the equity/asset ratio of all U.S. banks by 2006 was at an all-time high of over 10%.

Banks can offer new or improved products to their customers; they can lower operating costs and reduce risk through technological developments.

Front-Office Benefits

Automated teller machine (ATM) networks allow consumers to perform simple banking transactions at any time without waiting in line during banking hours. Improved funds transfer systems and automatic debits/ credits reduce the need for paper-based payments. Improvements in automated clearing house functions allow near real-time transfer of funds accompanied with a substantial drop in transaction costs.

Internet banking, at the very least, provides access to relevant information for a customer from any location at any time. Some banks also allow transactions over the internet.

Back-Office Benefits

Cost shifts in payments processing have been substantial as Berger, Kashyap, and Scalise (1995) point out with two examples. Between 1979 and 1994 the real cost of processing a paper check rose from 1.99 cents to 2.53 cents while that for processing an electronic deposit fell from 9.10 cents to 1.38 cents.

Individual credit bureaus provide banks with instantaneous access to financial information on millions of individuals. Credit scoring systems allow banks to either augment their soft data or completely replace soft data with hard data on credit extension and loan pricing decisions to individuals.

Later developments fostered the creation of small business credit scoring systems which applies techniques for individual credit decisions to owners of small businesses, typically for loans up to $100,000. (See Berger, Frame, and Miller, 2005.)

Although the Glass-Steagall Act separated banking activities from securities activities, this separation began to erode in the 1980s. Securities firms offered MMMFs which had most features of bank checking and savings accounts (except for deposit insurance).

Furthermore, as bank loans began losing market share to fixed income securities, the Federal Reserve began loosening rules restricting securities activities of BHC nonbank-ing subsidiaries. Eventually, in 1989 the BGFRS authorized J. P. Morgan to underwrite corporate debt securities and later to underwrite stocks.

The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999 allowed securities firms and insurance companies to purchase banks, and allowed banks to underwrite insurance and securities. Mishkin (2004) provides a good description of the deregulation of banking activities.

Deregulation occurred between 1984 and 1994. Geographic deregulation will eventually create nationwide branching.

Changes in State Regulations

Prior to changes in federal legislation, state deregulation took place at two levels. In the mid-1980s individual states began to loosen regulations on intrastate branching, often moving from unit banking to limited branching and then to statewide branching.

At the same time, states began to form regional reciprocal relationships allowing MBHCs from neighboring states to buy in-state banks. The latter action created "su-perregional" banks in which one MBHC owned banks and branches in more than one state.

Federal Preemption of State Restrictions

At the federal level, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 (RNIBBEA) replaced 50 state entry laws over interstate banking. This is a rare example of federal banking laws preempting state banking laws.

This act initially allowed banking organizations to acquire banks in any state unless state law specifically prohibits. Hawaii was the only state to do so. Furthermore, under RNIBBEA BHCs could merge the banks they acquired into one bank with branches in different states. This has created interstate branching in 47 states. Texas, Montana, and Minnesota are the only states to opt out of this provision.

Upheaval of the post-Depression banking system has been profound, including the number of bank charters, bank offices, and banking efficiency.

Banking Consolidation

One result of geographic deregulation has been to sharply reduce the number of separately chartered banks while at the same time increase the number of bank branches. Since 1984 the number of bank charters has fallen by 50% from 14,500 to around 7,000. At the same time, the number of bank branches has increased dramatically. For example, the number of banking offices in 1984 was 56,376 while in late 2006 it was 80,473.

Consolidation has also reduced the number of cities hosting large banks. As DeYoung and Klier (2004) point out, the corporate headquarters of merged banks are usually found in locations with the least geographic restrictions in former years, abandoning former-unit banking locales such as Chicago, Dallas, and Houston.

Bank Performance

Jayaratne and Strahan (1997) indicate that branching deregulation has improved bank performance while simultaneously benefiting bank customers, as diversification has decreased loan losses as well as loan pricing. Schuermann (2004) concludes that banks are less vulnerable to the business cycle with increased diversification through geographic expansion.

The Prospects for Nationwide Branching

While any bank now has the ability to form a nationwide branch network with a single bank charter, it may not necessarily be economically feasible to do so, given the vast geographic area. This same question is being asked within the European Union with their "Single Market Programme" potentially creating continent-wide banking organizations, as well as in Eastern Europe and Latin America.

One problem relates to the ability of senior management, located at the lead bank headquarters, to control junior managers at affiliates. That is, can "best practices" at the lead bank be transmitted to affiliates? A second question refers to the agency cost of distance, that is, does the lead bank have the ability to monitor far-flung affiliates?

Berger and De Young (2006) demonstrate that there are economic benefits to geographic expansion through their study of the MBHCs over the 1985 to 1998 time period. With technological developments, lead bank managers are indeed able to pass down efficiency improvements to acquired affiliates with this control increasing over time after acquisition. Furthermore, with technological improvements, diseconomies of distance have decreased.

Berger (2003) also demonstrates that technological progress has diminished the role of relationship banking. As cited earlier, retail lending no longer requires a local relationship and small business credit scoring has allowed "soft data" of relationship banking to be replaced by "hard data" which does not require a local presence for small business loans up to $100,000.

Concentration into Top Banks

FDIC data indicate that total deposits of all banks with (nominal) assets over $1 billion have increased from 68% in 2002 to 85% by late 2006. The top five banking organizations now control 35% of total domestic deposits. As of 2007, Bank of America had an 11% national share and JPMorgan-Chase has an 8.4% total.

One obstacle to further consolidation with the largest banking organizations is the RNIBBEA restriction that no BHC can control more than 30% of deposits in a single state and no more than 10% nationally, except for acquisition of failed banks. Thus, it appears that Bank of America has already reached its concentration limit.

Although the U.S. banking system has witnessed profound structural changes in the two decades since the mid-1980s, it is likely to continue to be unique. Whether in the future the system will be emulated or admired is an open question.

We should expect to see bank concentration continue through BHC mergers. We should also expect to see further consolidation as MHBCs continue to convert their acquired affiliates into branches.

Extrapolating current trends such as OCC preeminence and concentration of assets in national banks into the future one might conclude that we are heading towards the ultimate demise of dual banking, finally ending with a handful of nationally chartered banks. However, this is not the likely outcome.

One unique feature that we should expect to continue is the existence of a relatively large number of small, single market banks. While we have observed that the number of bank charters has fallen by 50% percent from 1984 to 2005, this trend appears to be slowing. Although relationship banking has declined in importance, it is still viable for small and middle-sized firms that do not have a bond rating but seek credit over a given limit. As Berger, Frame, and Miller (2005) illustrate the use of credit scoring for approve/deny decisions stops at the $100,000 level. Thus, relationship banking will continue for the middle markets sector, at least for the foreseeable future, and the dual banking structure will persist.

The original risk-based capital rules of Basel I were vital, but changes are needed due to financial system developments over the past two decades. The Basel Committee on Bank Supervision (2003) provides some of the features of Basel II.

Basel II incorporates market risk into capital requirements because banks have moved from their "buy-and-hold" philosophy into more investment banking activities. Basel II also incorporates ratings agency data in setting capital ratios for corporate credit exposures. Instead of lumping all corporate credits into the Standard Risk bucket with a 100% weight, there is now a wider spectrum of risk weights, ranging from low weights for investmentgrade firms to high weights for speculative grade firms. Table 3.5 illustrates this refinement.

Table 3.5. Risk Weights for Corporate Credit Exposures Under Basle II

Credit Assessment | AAA to AA- | A+ to A- | BBB+ BB- | Below BB- | Unrated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Risk weight | 20% | 50% | 100% | 150% | 100% |

Basel II also encourages banks to use their own internal systems for capital requirements. It recognizes that individual banks may have a better grasp of the risks they face than regulators. This allows banks to use an internal ratings–based approach, which should lower capital requirements. Furthermore, Basel II allows large banks to use an advanced internal ratings–based approach, replacing more standard "one bank fits all" data with internal data, including credit scoring data.

It is apparent the Basel II approach will continue as financial engineering progresses beyond current derivative and structured finance products. While these products can indeed transfer risk, they can also concentrate risk in ways that have not been tested or observed at this time.

Mishkin (2004) describes the U.S. regulatory system as a "crazy quilt of multiple regulatory agencies with overlapping jurisdictions." As illustrated above we are unique in having dual banking as well as having three federal agencies with nationwide examining functions. However, no agency will voluntarily cede examination and regulatory authority. Bank chartering agencies claim they need to know the condition of a troubled institution in order to make the decision to pull the charter. Similarly, the FDIC needs to know the condition of the bank when it insures deposits. Kohn (2004) notes that when Chase switched from a national to a state charter in 1995, the OCC lost 2% of its budget.

But it may not be as redundant as it appears in Table 3.2, in that state bank examiners often share tasks with federal examiners on a coordinated examination. To streamline the system, it would appear that the examining function of the Federal Reserve Banks could be jettisoned, but it doesn't seem likely at the present time.

One unanswered question at this time is the continued separation of depositories from nonfinancial businesses. Although industrial loan companies have historically played an insignificant role in the U.S. financial system Ergungor and Thompson (2006) point out that between 1987 and 2005 assets have risen from $3.8 billion to $140 billion with the largest ILC now having assets exceeding $66 billion. Furthermore, although FDIC insurance was not originally available to ILCs, the Garn–St. Germain Act of 1982 extended insurance to this sector. Today, seven states charter ILCs and the ILC charter is effectively the only vehicle by which nonfinancial firms can enter banking. Recent nonfinancial-depository combinations include Toyota, GMAC, Target, and Home Depot, which own large ILCs offering a variety of financial services. As of 2005, the 10 largest ILCs include Merrill Lynch Bank USA, UBS Bank USA, American Express Centurion Bank, Fremont Investment & Loan, Morgan Stanley Bank, USAA Savings Bank, GMAC Commercial Mortgage Bank, GMAC Automotive Bank, Beal Savings Bank, and Lehman Brothers Commercial Bank.

Federal bank regulators are at odds over this topic with the FDIC supporting ILCs in the current form and BGFRS arguing for a change in the 1956 definition of "bank" to bring ILCs and their nonfinancial parent under the board's supervision.

Over a very short time, the American banking system has progressed from one that was segmented by product line and geography into one allowing universal banking and nationwide branching. With risk-based capital rules, product and geographic deregulation and universal access to the Fed's discount window, today's banking system has lower costs and less risk than the system of the past.

Basel Committee on Bank Supervision. (2003). Quantitative Impact Statement 3. [Available at www.bis.org/bcbs/qis/qis3.htm.]

Berger, A. N. (2003). The economic effects of technological progress: Evidence from the banking industry. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 35, 2: 141–176.

Berger, A. N., and De Young, R. (2006). Technological progress and the geographic expansion of the banking industry. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 38, 6: 1483–1513.

Berger, A. N., Dick, A. A., Goldberg, L. G., and White, L. J. (2005). Competition from large, multimarket firms on the performance of small, single-market firms: evidence from the banking industry. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2005-15, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Berger, A. N., Kashyap, A. K., and Scalise, J. M. (1995). The transformation of the U.S. banking industry: What a long, strange trip it's been. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2: 55–218.

Berger, A. N., Frame, W. S., and Miller, N. H. (2005). Credit scoring and the availability, price and risk of small business credit. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 37, 2: 191–222.

Brevoort, K. P., and Hannan, T. H. (2006). Commercial lending and distance: evidence from community reinvestment act data. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 38, 8: 1991–2012.

Calomiris, C. W. (2000). U.S. Bank Deregulation in Historical Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, E., and Rice, T. (2006). Federal preemption of state bank regulation: a conference panel summary. Chicago Fed Letter, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

De Young, R., and Klier, T. (2004). Why Bank One left Chicago: One piece in a bigger puzzle. Chicago Fed Letter, April.

Ergungor, O. E., and Thomson, J. B. (2006). Industrial Loan Companies. Economic Commentary. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Fields, L. P., Fraser, D. R., Berry, T. L., and Byers, S. (2006). Do bank loan relationships still matter? Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 38, 5: 1195–1209.

Frame, W. S., Srinivasan, A., and Woosley, L. (2001). The effect of credit scoring on small-business lending. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 33, 3: 813–825.

Giles, R. P. (1983). A Model of the U.S. Correspondent Banking System, Unpublished PhD thesis, Columbia University.

Hannan, T. H., and Prager, R. A. (2006). The profitability of small, single-market banks in an era of multimarket banking. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2006-41, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System.

Hirtle, B., Levonian, M., Saidenberg, M., Walter, S., and Wright, D. (2001). Using credit risk models for regulatory capital: Issues and options. Economic Policy Review, Federal Reserve Bank of New York 7, 1: 21–35.

Jayaratne, J., and Strahan, P. E. (1997). The benefits of branching deregulation. Economic Policy Review, Federal Reserve Bank of New York (December).

Janicki, H. P., and Prescott, E. S. (2006). Changes in the size distribution of U.S. banks: 1960–2005. Economic Quarterly, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond 92, 4: 291– 316.

Jones, K. D., and Crichfield, T. (2005). Consolidation in the U.S. banking industry: Is the "long, strange trip" about to end? FDIC Banking Review 17, 4: 31–61.

Kohn, M. (2004). Financial Institutions and Markets, 2nd edition. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mishkin, F. (2004). The Economics of Money, Banking and Financial Markets, 7th edition. New York: Pearson.

Petersen, M. A., and Rajan, R. G. (2002). Does distance still matter? The information revolution in small business lending. Journal of Finance 57, 6: 2533–2570.

Radecki, L. J. (1998). The expanding geographic reach of retail banking markets. Economic Policy Review, Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Schuermann, T. (2004). Why were banks better off in the 2001 recession? Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York 10, 1.

Spong, K. (2000). Bank Regulation: Its Purposes, Implementation, and Effects, 5th edition. Division of Supervision and Risk Management, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Tirtiroglu, D., Daniels, K. N., and Tirtiroglu, E. (2005). Deregulation, intensity of competition, industry evolution, and the productivity growth of U.S. commercial banks. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 37, 2: 339–360.

Tracey, W. F., and Carey, M. (2000). Credit risk rating systems at large U.S. banks. Journal of Banking and Finance 24: 167–201.

Walter, J. R. (2006). Not your father's credit union. Economic Quarterly, Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond 92, 4: 353–377.