FRANK J. FABOZZI, PhD, CFA, CPA

Professor in the Practice of Finance, Yale School of Management

GERALD W. BUETOW, PhD, CFA

President and Founder, BFRC Services, LLC

Abstract: One of the major innovations in the financial markets has been the interest rate swap. This instrument is a derivative product that was introduced into the financial markets in the early 1980s. Interest rate swaps were first used to try to arbitrage opportunities in global capital markets. While those arbitrage opportunities quickly disappeared, the interest rate swap market continued to grow. Today, this derivative instruction provides asset managers, risk managers, corporate treasurers, and municipal treasurers with an efficient tool for controlling interest rate risk by altering the cash flow characteristics of their assets or liabilities.

Keyword: interest rate swap, plain vanilla swap, fixed-rate payer, swap fixed rate, swap rate, fixed-rate receiver, floating-rate receiver, floating-rate payer, cash flow for the swap, swap spread, swap dealer, counterparty risk, amortizing swap, accreting swap, basis swap, constant maturity swap (CMS), forward rate swap, swaption, payer's swaption, receiver's swaption

The objective of this chapter is to explain the basic features of an interest rate swap and provide an economic interpretation of this derivative instrument. Interest rate swaps include plain vanilla swaps, amortizing swaps, accreting swaps, basis swaps, constant maturity swaps, forward rate swaps, and swaptions. The valuation of interest rate swaps and the factors that affect the value of a swap are explained in Chapter 44 of Volume III for a plain vanilla swap, amortizing, and accreting swap and Chapter 45 of Volume III for a forward rate swap and a swaption.

In an interest rate swap, two parties agree to exchange interest payments at specified future dates. The dollar amount of the interest payments exchanged is based on some predetermined dollar principal, which is called the notional principal or notional amount. The payment each party pays to the other is the agreed-upon periodic interest rate times the notional principal. The only dollars that are exchanged between the parties are the interest payments, not the notional principal.

In the most common type of swap, one party agrees to pay the other party fixed interest payments at designated dates for the life of the contract. This party is referred to as the fixed-rate payer. The fixed rate that the fixed-rate payer must make is called the swap fixed rate or swap rate. The other party, who agrees to make payments that float with some reference rate, is referred to as the fixed-rate receiver. The fixed-rate payer is also referred to as the floating-rate receiver and the floating-rate payer is also called the floating-rate receiver. The type of swap that we have just described is called a plain vanilla swap. The fixed-rate payer (floating-rate receiver) and floating-rate payer (fixed-rate receiver) are counterparties to the swap.

The reference rates that have been used for the floating rate in an interest rate swap are those on various money market instruments: the London interbank offered rate, Treasury bills, commercial paper, bankers acceptances, certificates of deposit, the federal funds rate, a constant maturity Treasury rate, and the prime rate. The most common is the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR). LIBOR is the rate at which prime banks offer to pay on Eurodollar deposits available to other prime banks for a given maturity. Basically, it is viewed as the global cost of bank borrowing. There is not just one rate but a rate for different maturities. For example, there is a 1-month LIBOR, 3-month LIBOR, 6-month LIBOR, and so on.

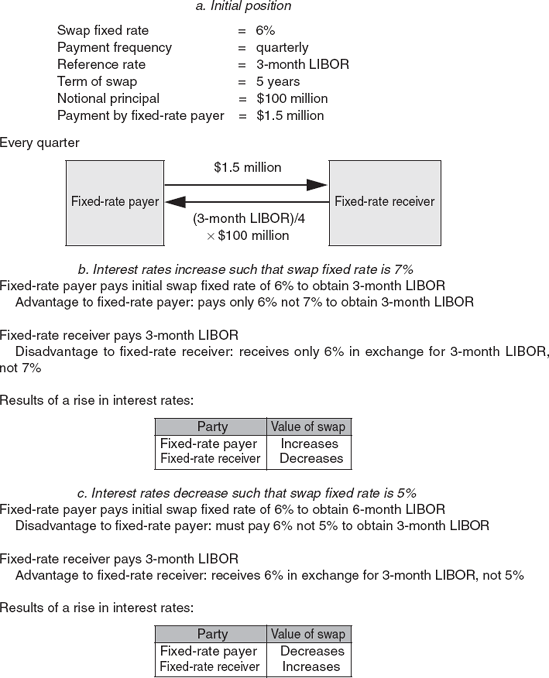

To illustrate a plain vanilla interest rate swap, suppose that for the next five years party X agrees to pay party Y 6% per year (the swap fixed rate), while party Y agrees to pay party X 3-month LIBOR (the reference rate). Party X is the fixed-rate payer, while party Y is the fixed-rate receiver. Assume that the notional principal is $100 million, and that payments are exchanged every three months for the next five years. This means that every three months, party X (the fixed-rate payer) will pay party Y $1.5 million (6% times $100 million divided by 4). The amount that party Y (the fixed-rate receiver) will pay party X will be 3-month LIBOR times $100 million divided by 4. If 3-month LIBOR is 5%, party Y will pay party X $1.25 million (5% times $100 million divided by 4). Note that we divide by four because one-quarter of a year's interest is being paid. (We will be more precise about the days in the period for determining the payments in the next chapter.) This is illustrated in panel a of Figure 40.1

The payments between the parties are usually netted. In our illustration, if the fixed-rate payer must pay $1.5 million and the fixed-rate receiver must pay $1.25 million, than rather than writing checks for the respective amounts, the fixed-rate party can just make a payment of $0.25 million (= $1.5 million – $1.25 million) to the fixed-rate receiver. We shall refer to this netted payment between the two parties as the cash flow for the swap for the period. We note that throughout the literature the terms "swap payments" and "cash flows" are used interchangeably. However, in this chapter we will use the term swap payments to mean the payment made by a counterparty before any netting and cash flow to mean the netted amount.

The convention that has evolved for quoting a swap fixed rate is that a dealer sets the floating rate equal to the reference rate and then quotes the swap fixed rate that will apply. The swap fixed rate is some "spread" above the Treasury yield curve with the same term to maturity as the swap. This spread is called the swap spread.

Interest rate swaps are over-the-counter (OTC) instruments. This means that they are not traded on an exchange. A party wishing to enter into a swap transaction can do so through either a securities firm or a commercial bank that transacts in swaps. These entities can do one of the following. First, they can arrange or broker a swap between two parties that want to enter into an interest rate swap. In this case, the investment bank or commercial bank (simply bank hereafter) is acting in a brokerage capacity. The broker is not party to the swap.

The second way in which a bank can get a party into a swap position is by taking the other side of the swap. This means that the bank is acting as a dealer rather than a broker in the transaction. Acting as a dealer (which we refer to as a swap dealer) the bank is a counterparty to the swap and therefore must hedge its swap position in the same way that it hedges its position in other securities that it holds. Also it means that the dealer is the counterparty to the transaction. If a party entered into a swap with a swap dealer, the party will look to the swap dealer to satisfy the obligations of the swap; similarly, that same swap dealer looks to the counterparty to fulfill its obligations as set forth in the swap agreement.

The risk that the two parties take on when they enter into a swap is that the other party will fail to fulfill its obligations as set forth in the swap agreement. That is, each party faces default risk and therefore there is bilateral counterparty risk.

The value of an interest rate swap will fluctuate with market interest rates. To see how, let's reconsider our hypothetical swap. Suppose that interest rates change immediately after parties X and Y enter into the swap. Panel a in Figure 40.1 shows the transaction. First, consider what would happen if the market required that in any 5-year swap the fixed-rate payer must pay a swap fixed rate of 7% in order to receive 3-month LIBOR. If party X (the fixed-rate payer) wants to sell its position to party A, then party A will benefit by having to pay only 6% (the original swap fixed rate agreed upon) rather than 7% (the current swap fixed rate) to receive 3-month LIBOR. Party X will want compensation for this benefit. Consequently, the value of party X's position has increased. Thus, if interest rates increase, the fixed-rate payer will realize a profit and the fixed-rate receiver will realize a loss. Panel b in Figure 40.1 summarizes the results of a rise in interest rates.

Next, consider what would happen if interest rates decline to, say, 5%. Now a 5-year swap would require the fixed-rate payer to pay 5% rather than 6% to receive 3-month LIBOR. If party X wants to sell its position to party B, the latter would demand compensation to take over the position. In other words, if interest rates decline, the fixed-rate payer will realize a loss, while the fixed-rate receiver will realize a profit. Panel c in Figure 40.1 summarizes the results of a decline in interest rates.

There are two classic ways that a swap position can be interpreted: (1) a package of futures (forward) contracts and (2) a package of cash flows from buying and selling cash market instruments. These interpretations will help us understand how to value swaps and how to assess the sensitivity of a swap's value to changes in interest rates. A third, more complicated interpretation, uses caps and floors. Specifically, a portfolio consisting of a long cap and a short floor struck such that the net cost is zero is equivalent to a plain vanilla swap. We do not discuss this interpretation because of the complex nature of interest rate options.

Contrast the position of the counterparties in an interest rate swap to the position of a long and short price-based interest rate futures (rate-based forward) position. The long futures (short forward position) position gains if interest rates decline and loses (gains) if interest rates rise; this is similar to the risk/return profile for a fixed-rate receiver. The risk/return profile for a fixed-rate payer is similar to that of short futures position (long forward position): there is a gain if interest rates increase and a loss (gain) if interest rates decrease. By taking a closer look at the interest rate swap we can understand why the risk/return profile are similar.

Consider party X's position in our swap illustration. Party X has agreed to pay 6% and receive 3-month LIBOR. More specifically, assuming a $100 million notional principal, party X has agreed to buy a commodity called "3-month LIBOR" for $1.5 million. This is effectively a 3-month forward contract where party X agrees to pay $1.5 million in exchange for delivery of 3-month LIBOR. If interest rates increase to 7%, the price of that commodity (3-month LIBOR) in the market is higher, resulting in a gain for the fixed-rate payer, who is effectively long a 3-month forward contract on 3-month LIBOR. The fixed-rate receiver is effectively short a 3-month forward contract on 3-month LIBOR. There is therefore an implicit forward contract corresponding to each exchange date.

Now we can see why there is a similarity between the risk/return profile for an interest rate swap and a forward contract. If interest rates increase to, say, 7%, the price of that commodity (3-month LIBOR) increases to $1.75 million (7% times $100 million divided by 4). The long forward position (the fixed-rate payer) gains, and the short forward position (the fixed-rate receiver) loses. If interest rates decline to, say, 5%, the price of our commodity decreases to $1.25 million (5% times $100 million divided by 4) The short forward position (the fixed-rate receiver) gains, and the long forward position (the fixed-rate payer) loses.

Consequently, interest rate swaps can be viewed as a package of more basic interest rate derivatives such as price-based futures of rate-based forward contracts. The pricing of an interest rate swap will then depend on the price of a package of forward contracts with the same settlement dates in which the underlying for the forward contract is the same reference rate. This principle is used when valuing swaps.

While an interest rate swap may be nothing more than a package of forward contracts, it is not a redundant contract for several reasons. First, maturities for forward or futures contracts do not extend out as far as those of an interest rate swap; for example, an interest rate swap with a term of 10 years or longer can be obtained. Second, an interest rate swap is a more transactionally efficient instrument. By this we mean that in one transaction an entity can effectively establish a payoff equivalent to a package of futures or forward contracts. Third, the interest rate swap market has grown in liquidity since its introduction in 1981; interest rate swaps now provide more liquidity than forward contracts, particularly long-dated (that is, long-term) forward contracts.

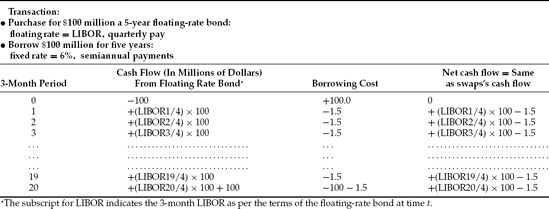

To understand why a swap can also be interpreted as a package of cash market instruments, consider an investor who enters into the following transaction:

Buy $100 million par of a 5-year floating-rate bond that pays 3-month LIBOR every three months.

Finance the purchase by borrowing $100 million for five years on terms requiring a 6% annual interest rate paid every three months.

As a result of this transaction, the investor

Receives a floating rate every three months for the next five years.

Pays a fixed rate every three months for the next five years. Has no initial outlay.

The cash flows for this transaction are set forth in Table 40.1. The second column of the exhibit shows the cash flows from purchasing the 5-year floating-rate bond. There is a $100 million cash outlay and then 20 cash inflows. The amount of the cash inflows is uncertain because they depend on future LIBOR. The next column shows the cash flows from borrowing $100 million on a fixed-rate basis. The last column shows the net cash flows from the transaction. As the last column indicates, there is no initial cash flow (no cash inflow or cash outlay). In all 20 of the 3-month periods, the net position results in a cash inflow of LIBOR and a cash outlay of $1.5 million. This net position is identical to the position of a fixed-rate payer.

Table 40.1. Cash Flows for the Purchase of a 5-Year Floating-Rate Bond Financed by Borrowing on a Fixed-Rate Basis

|

It can be seen from the net cash flow in Table 40.1 that a fixed rate payer has a cash market position that is equivalent to a long position in a floating-rate bond and a short position in a fixed-rate-bond—the short position being the equivalent of borrowing by issuing a fixed-rate bond.

What about the position of a fixed-rate receiver? It can be easily demonstrated that the position of a fixed-rate receiver is equivalent to purchasing a fixed-rate bond and financing that purchase at a floating rate, where the floating rate is the reference rate for the swap. That is, the position of a fixed-rate receiver is equivalent to a long position in a fixed-rate bond and a short position in a floating-rate bond.

The terminology used to describe the position of a party in the swap market combines cash market jargon and futures market jargon. This is not surprising given that a swap position can be interpreted as a position in a package of cash market instruments or a package of futures/forward positions. As we have said, the counterparty to an interest rate swap is either a fixed-rate payer or fixed-rate receiver.

Table 40.2 lists how the counterparties to an interest rate swap agreement are described. To understand why the fixed-rate payer is viewed as "short the bond market," and the fixed-rate receiver is viewed as "long the bond market," consider what happens when interest rates change. Being short the bond market implies that the position becomes profitable when interest rates increase; long the bond market implies that the position becomes profitable when interest rates decrease. Those who borrow on a fixed-rate basis will benefit if interest rates rise because they have locked in a lower interest rate. But those who have a short bond position will also benefit if interest rates rise. Thus, a fixed-rate payer can be said to be short the bond market since both legs of the swap become more profitable when interest rates increase. A fixed-rate receiver benefits if interest rates fall since both legs of the swap becomes more profitable when interest rates decrease. A long position in a bond also benefits if interest rates fall, so terminology describing a fixed-rate receiver as long the bond market is not surprising. From our discussion of the interpretation of a swap as a package of cash market instruments, describing a swap in terms of the sensitivities of long and short cash positions follows naturally.

Table 40.2. Describing the Parties to a Swap Agreement

Fixed-rate payer | Fixed-rate receiver |

|---|---|

• pays fixed rate in the swap | • pays floating rate in the swap |

• receives floating in the swap | • receives fixed in the swap |

• is short the bond market | • is long the bond market |

• has bought a swap | • has sold a swap |

• is long a swap | • is short a swap |

• has established the price sensitivities of a longer-term liability and a floating-rate asset | • has established the price sensitivities of a longer-term asset and a floating-rate liability |

Thus far we have provided a description of a plain vanilla swap. There are other types of swap structures—simple extensions and complex structures. We describe some of these in this section.

A simple extension of the plain vanilla swap is one in which the notional principal changes based on a specified schedule. A plain vanilla swap in which the notional principal decreases over time is called an amortizing swap. When the notional principal increases over time, the swap is referred to as an accreting swap. As we will see, once we know how to value a plain vanilla swap where the notional principal is constant over the life of the swap, it is a simple matter to value one with a varying notional principal.

There are swaps where both parties pay a floating rate based on two reference rates. For example, one party can make payments based on the 3-month Treasury bill rate plus some spread and the other party make payments based on 3-month LIBOR. Swaps where both parties make floating payments like the one just described are called basis swaps. Swaps can have the floating leg based on a reference rate other than LIBOR. For example, the floating leg might be based on the 2-year U.S. Treasury note yield. Swaps tied to U.S. Treasuries are referred to as Constant Maturity Treasury (CMT) swaps. Other intermediate-term floating reference rates are called constant maturity swaps (CMSs). A CMT is an example of a CMS. CMSs can either be structured in the basis swap framework (floating for a floating) or traditional (fixed for non-LIBOR-based floating).

Two complex swap structures are (1) a swap that starts at some future date and (2) an option on a swap. A swap that starts at some future date is called a forward start swap. An example of a forward start swap would be one where the obligation starts now but the swap starts two years from now and matures three years later for a total of five years. The swap fixed rate for the forward start swap is determined at the inception of the obligation. Swaps that combine some or all of these characteristics are also possible.

An option on a swap gives the owner of the option the right to enter into a swap at some future date. An option on a swap is called a swaption. A payer's swaption is one in which the owner of the option has the right to enter into a swap to pay a fixed rate and receive a floating rate. A receiver's swaption is one in which the owner of the option has the right to enter into a swap to receive a fixed rate and pay a floating rate. The swap fixed rate is the strike rate of the swaption.

An interest rate swap is a derivative instrument. In this chapter, we have explained the basic features of interest rate swaps. The parties to the contract agree to exchange interest payments at specified future dates based on a notional amount. In a plain vanilla swap, over the life of the contract, one party agrees to pay the other party fixed interest payments based on the swap rate and the other party agrees to make floating-rate payments based on a specified reference rate. A swap position can be interpreted in two ways. First, it is equivalent to a position in a package of futures (forward) contracts. Second, it is equivalent to a position in a package of cash flows from buying and selling cash market instruments.

There are different types of interest rate swaps. These include interest rate swaps, plain vanilla swaps, amortizing swaps, accreting swaps, basis swaps, constant maturity swaps, forward rate swaps, and swaptions.

Brown, K. C, and Smith, D. J. (1995). Interest Rate and Currency Swaps: A Tutorial. Charlottesville, VA: The Research Foundation of the Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts.

Buetow, G. W., and Fabozzi, F. J. (2001). Valuation of Interest Rate Swaps and Options. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Chisholm, A. M. (2004). Derivatives Demystified: A Step-by-Step Guide to Forwards, Futures, Swaps and Options. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Flavell, R. (2002). Swap and Other Derivatives. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

Kopprasch, R. F, Macfarlane, J., Showers, J., and Ross, D.R. (1991). The interest rate swap market: Yield mathematics, terminology, and conventions. In F J. Fabozzi (ed.), The Handbook of Fixed Income Securities, 3rd edition (pp. 1189-1217), Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin.

Ludwig, M. S. (1993). Understanding Interest Rate Swaps. New York: McGraw Hill.

Marshall, J. F, and Kapner, K. R. (1993). Understanding Swaps. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Whaley, R. E. (2006). Derivatives: Markets, Valuation, and Risk Management. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.