RACHEL A. J. CAMPBELL, PhD

Assistant Professor of Finance, Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University & Maastricht University, The Netherlands

Abstract: Art finance is a rapidly developing area of international finance. Although direct investment in art is not new, structured solutions to investing in art indirectly mean that art is being considered an alternative asset class. A number of art funds have recently been launched, and a number of smaller boutique funds actively invest and trade in art, purely for financial gain. With the increasing amount of money pouring into the art market, banks are becoming increasingly interested in using art as collateral. Understanding how art is priced, as well as the risk and return characteristics of art is fundamental to portfolio management in all areas of art finance, when considering art as an alternative asset and the development of art banking and art finance.

Keywords: art banking, alternative investment, art funds, art indices, art pricing, risk and return

Artworks have been trading in auction markets and private dealer markets for centuries, so the concept of trading art is not a new phenomenon. Trading portfolios of artworks for pure financial gain and using art as an asset with an underlying value from which to obtain finance is a much more recent phenomenon.

Typically, turnover in the market is dominated by fine art paintings, making up 75% of the number of art sales; drawings and watercolors and sculptures represent a further 10% each, with prints and photography taking the smaller 5% final share of the market. (See Artprice for an annual report on these figures.) We focus in this chapter on the market for fine art, and exclude the market for decorative art. The majority of the world's art is traded in New York, attracting 50% of global art auction sales, with London taking 25%. These two trading hubs dominate the global auction market, with 75% of the global market. France and China take a smaller 5% share each, with the other 20% split between other smaller markets. The two major auction houses are Christie's and Sotheby's, who dominate the market, commanding the lion's share of auction sales, with each house taking almost 40% of all auction sales. Figures on dealer markets are illusive, with prices attained by private dealers difficult to obtain. It is thought that the dealer market represents between 40% and 60% of the total art market. With growing economic prosperity in China and India, the major auction houses have opened auction houses at the local level, with trade in indigenous art currently booming. Both repatriation and a growing interest by Western collectors and investors for Asian art are creating enormous demand in this area.

The art market is changing dramatically, and growing rapidly with continued increase in the demand for contemporary art; other sectors of the art market show continued steady growth. (See Goodwin [2007] for an overview of the global art market.) Art finance is a relatively new area of international finance, which covers both the concept of art investment, as well as using art as an underlying asset for finance.

The vogue for investing in fine art has received a boost from the availability of greater information on art prices. Demand is growing, resulting in record prices being reached, and buyers are able to trace previous prices of artworks through a number of data providers. Databases, indices, and market reports are now essential analytical tools with which art investors can assess financial performance.

The use of a variety of indices for various art markets enables us to get a good impression of the returns which fine artworks have made historically and the amount of risk associated with these art prices. This in turn is useful for analyzing art as an investment, for looking at the performance of art funds, and in giving an indication of art's performance in a diversified portfolio.

The Mei Moses index, Art Market Research, and art price indices are the three most widely quoted indicators of art market performance. All are reliant on data from sales obtained from the two main auction houses. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, auction results alone provide an incomplete picture of the market performance because they are only a portion of the whole market. The dealer market is largely ignored due to this absence of obtainable data. Although there is some disagreement as to the percentage of the market that dealers comprise, it cannot be denied that dealers have a significant, albeit unquantifiable, impact on the art market. The absence of dealers' transactions from the art indices may have a bearing on the rate of return indicated by the indices. This is due to the fact that dealers may buy at lower prices but sell at higher prices, thereby reducing the art investors' rate of return.

Historically, moderate returns have been made financially from investing in art. The return made by art can be split into a financial return and a nonfinancial return, which comes in the form of aesthetic value from holding the artwork. The presence of a nonfinancial return means that the return made by art, when looking at it from a purely financial perspective, tends to be only moderate, especially when compared with other alternative asset classes with comparable levels of risk. It could be argued that the aesthetic value earned by the holder of the artwork is not valued or included in the financial gain and thus not compensated for financially by the level of risk held.

There are four main methodologies for producing art price indices: geometric means, average prices, repeat sales regressions (RSR), and hedonic regressions. Chanel, Gerard-Varet, and Ginsburgh's (1996) study indicates that over long periods the respective methodologies are closely correlated. Issues regarding the various index pricing methodologies are extremely well highlighted in a recent paper by Ginsburgh, Mei, and Moses (2007), which specifically compares hedonic to repeat sales regression.

Hedonic valuation takes into account the characteristics of the artworks. An examination of the subject matter, size, medium, provenance, and condition of the artwork, as well as the artist's popularity, will all materially contribute to the financial value an artwork is given. While many of these are necessarily objective inquiries, it is ultimately the subjective opinion of the purchaser that will be determinative of the price paid. Therefore, unlike stocks and bonds, the price of an artwork comprises an unquantifiable element: taste. For a collector, taste will play an important role in determining whether an artwork is bought.

Ashenfelter and Graddy (2003) provide an excellent survey of average returns estimated from art price data, currently in the academic literature. We have extended the exhibit with a few additional studies; see Table 58.1, which provides estimates of the levels of risk and return over various periods.

These indices show that historically, average real returns for fine art are moderate. Returns are above inflation and tend to be greater than for government bonds, but less than for equities.

The survey of art pricing methodologies in Table 58.1 tends to indicate that the repeat sales methodology provides slightly higher estimates of average returns than the other methodologies for similar time periods. For example, Anderson (1974) provides RSR and hedonic price indices for the periods 1780-1970 and 1780-1960 and Chanel, Gerard-Varet, and Ginsburgh (1996) for the period 1855-1969. It is of interest to observe the long-run trend in the market, and to note that there have been periods in which art returns have been substantially higher than average.

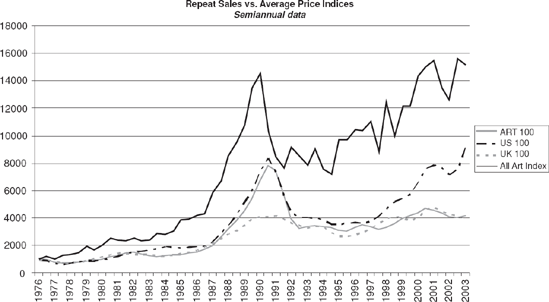

There has been a general upward trend in art prices in the market. Figure 58.1 shows the performance of a $1,000 investment in the art market over the period 1976-2003. This is purely theoretical, since trading such an index is not presently possible.

We see that the repeat sales estimates provide a significantly greater estimate of average return over the period than the average prices from Art Market Research. Caution should be urged in using too high an estimate for past historical average returns in forecasting expected returns, due to this upward bias in using the repeat sale methodology. Also, the indices provided do not take account of transaction costs, which can represent a significant fraction.

With the collection and availability of art price data, the concept of art market finance is beginning to flourish. Many of the larger banks offer art banking services, and the opportunity to lend against art as collateral. With the proliferation of repeat sales indices, which give a good estimate of the financial return for various artworks over time, there is a booming interest in considering art as an alternative investment.

The continued search for alternative asset classes, which exhibit historically low correlations with the more traditional asset classes, render the art market as an attractive avenue to reaping benefits from portfolio diversification. Although notoriously illiquid at times, the art market appears to offer investors an alternative asset class that is only slightly correlated with most other asset classes. The highest correlation exhibited over a 30-year period was with commodities, still less than 10% (see Campbell, 2008). Others sources of risk—above all, liquidity risk—mean that it is difficult to assess the true risk/return tradeoff in this market; however, with the greater amount of data available on the prices at which artworks are sold, financial analysis and research into the art market is becoming widespread.

Table 58.1. Estimated Fine Art Market Performance, Seventeenth through Twenty-first Century (as reported by various academic papers by period of study)

Author (Year Published) | Sample | Period | Method | Nominal Return | Real Return | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Baumol (1986) | Paintings in general | 1652-1961 | RSR | 0.60% | ||

Frey and Pommerehne (1989) | Paintings in general | 1635-1949 | RSR | 1.40% | ||

1653-1987 | RSR | 1.50% | 5.00% | |||

1950-1987 | RSR | 1.70% | ||||

Buelens and Ginsburgh (1992) | Paintings in general | 1700-1961 | Hedonic | 0.91% | ||

Paintings in general | 1780-1970 | RSR | 3.70% | 3.00%[a] | ||

Goetzmann (1993) | Paintings in general | 1716-1986 | RSR | 3.20% | 2.00%[a] | 5.65% |

1850-1986 | RSR | 6.20% | 3.80% | 6.50% | ||

1900-1986 | RSR | 17.50% | 13.3% | 5.19% | ||

Anderson (1974) | Paintings in general | 1780-1960 | Hedonic | 3.30% | 2.60%[a] | |

1780-1970 | RSR | 3.70% | 3.00%[a] | |||

Chanel, Gerard-Varet, and Ginsburgh (1996) | Paintings in general | 1855-1969 | Hedonic | 4.90% | ||

1855-1969 | RSR | 5.00% | ||||

Mei and Moses (2002) | American, impressionists and old masters | 1875-1999 | RSR | 4.90% | 4.28% | |

1900-1986 | RSR | 5.20% | 3.72% | |||

1900-1999 | RSR | 5.20% | 3.55% | |||

1950-1999 | RSR | 8.20% | 2.13% | |||

1977-1991 | RSR | 7.80% | 2.11% | |||

Goetzmann (1996) | Paintings in general | 1907-1977 | RSR | 5.00% | ||

Fase (1996) | Nineteenth century | 1946-1966 | 11.00% | 7.50% | ||

1972-1992 | 10.60% | 1.10% | ||||

Stein (1977) | Paintings in general | 1946-1968 | Geometric Mean | 10.47% | ||

Barre, Docclo, and Ginsburgh (1996) | Great impressionist | 1962-1991 | Hedonic | 12.0% | 5.00%[a] | |

Other impressionist | 1962-1991 | Hedonic | 8.00% | 1.00%[a] | ||

Czujack (1997) | Picasso paintings | 1966-1994 | Hedonic | 8.30% | ||

Deutschman (1991) | Old masters | 1971-1991 | 12.30% | 6.04% | ||

Angnello and Pierce (1996) | Nineteenth Century U.S. | 1971-1992 | 9.30% | 3.25% | ||

Campbell (2005) | Paintings in general | 1976-2004 | Average prices | 5.73% | 1.44% | 8.27% |

U.S. paintings | 1976-2004 | Average prices | 7.94% | 3.66% | 8.73% | |

Pesando (1993) | Modern prints | 1977-1992 | RSR | 1.51% | 19.94% | |

Pesando and Shum (1996) | Picasso prints | 1977-1992 | RSR | 12.00% | 2.10% | 23.38% |

Frey and Serna (1990) | Old masters | 1981-1988 | Hedonic | 10.59% | 3.20% | |

Candela and Scorcu (1997) | Modern contemporary paintings | 1983-1994 | 3.89% | 0.21% | ||

[a] Real returns estimated additionally by Ashenfelter and Graddy (2003). | ||||||

Although returns are only moderate, especially when including transaction costs, the benefits arising from investing in art is that the price of art appears to be only slightly correlated with other financial asset classes. This renders a small investment in art as beneficial addition to an investment portfolio because for the same amount of return less risk in encountered. That is to say, the low correlation is highly desirable from a diversification perspective, which reduces the overall volatility—and thus the risk of the investment portfolio. Even though art is highly volatile alone, if held in conjunction with stocks and bonds in a portfolio, then the investor is able to obtain higher expected returns than otherwise for a given level of risk.

Moreover, diversification benefits can be gained within the art market itself. Holding a broad portfolio of artworks from a variety of styles (old masters, impressionists, modern, and contemporary, to name a few), and across countries and artists, can reduce the overall risk of the art portfolio considerably. It is unclear just how many artworks are required to completely reduce the unsystematic risk from art prices, so that the art market index risk and return profile is met—indeed, it is likely to be more than a stock portfolio. However, with indices from various styles and countries available (see Art Market Research), correlation statistics between the various "art industries" offer attractive diversification benefits to the art investor.

Investment skill lies in interpreting the available information, assessing whether the risk/return ratio is acceptable, and in deciding whether the investment is appropriate to an existing portfolio. In the art market this is extremely subjective. Taste adds an additional, unquantifiable element to art investment even after market analysis has been undertaken. Considering art as a direct investment presents a risky investment opportunity, although purchasing according to personal taste means that the aesthetic benefit is also received, which could potentially outweigh any financial benefit or loss incurred.

Repeat sales All Art Index versus the average price indices from Art Market Research for the general art market (Art 100), a basket of U.S. artists (U.S. 100) and a basket of British artists (U.K. 100).

Market anomalies and inefficiencies can lead to much higher realized returns. With almost no regulation, market efficiencies in the art market are abundant. Many possibilities exist to trade legally on "insider information," gain from pricing discrepancies among markets, and to a great extent make the market.

Market participants can behave in a rather "irrational" manner, with paintings being bought as a status symbol, to exemplify one's wealth. Behavior at auction has been observed, resulting in an overexuberance with participants tending to overpay for objects, with prices hitting the hammer above what buyers had thought they would have been prepared to pay. This aversion to lose in a bidding process, and other such emotive reasons, appear to have a large impact on the market than in other financial asset classes.

There are a number of standard market anomalies that have been observed in the market for art. See Ashenfelter and Graddy (2003) for a detailed overview of some of these irregularities, which have been documented in the academic literature. For example, the law of one price does not consistently hold, higher prices paid for burned artworks (artworks not having sold previously at auction and bought in), declining prices paid for similar objects. These behavioral aspects of market participants can lead to inefficiencies in the art market, and thus for the ability of less emotive art funds (who are dispassionate about the art and interested only in the financial return) to reap higher returns than a benchmark index. Moreover, the lack of liquidity in the market means that buyers with no liquidity constraints can pick up artworks at relatively undervalued prices simply by providing immediate liquidity. Often quoted in the art market are the forced sales arising from the three D's—debt, divorce, and death—which often require sales to be transacted at a faster pace, driving down the price received for such forced sales.

Art may also be attractive to investors seeking a diversified portfolio. First of all, a well-diversified portfolio of art needs to be held to reduce the risk of individual artists falling from fashion. Second, the low correlation between art and other financial assets means that art may form part of an optimal portfolio allocation, with investors holding a variety of assets such as equities, bonds, real estate, and art as well as cash. Estimating the correlation statistics among a variety of asset classes, we find art and equities are approximately 5% correlated over the past 30 years. The correlation between other asset classes is also low, the highest being between art and commodity futures, and even then only 10% correlated.

The irregularities of the market have led to the emergence of a number of art funds in recent years, whose proprietary strategy is in trading art for a speculative profit. The additional attraction is the low correlation that art prices appear to have with other financial asset classes, although the lack of liquidity during art market downturns must not be underestimated, and with fewer sales occurring during these periods, keeping correlation statistics down.

The first major fund to launch was the London-based Fine Art Fund in 2003. These types of funds act more like private equity funds, alternatively taking on strategies common to hedge funds, the newest of which is the Art Trading Fund, currently raising capital and run by a former hedge fund manager. Banks are also moving into the arena, with a failed attempt by ABN Amro for a fund-of-funds, and the recent launch of Societe General Alternative Asset Management with a fund out of Paris. With expert knowledge being a crucial factor in the success of these types of funds, only a handful of funds have been successful in attracting capital, with those having the dedicated resources and capabilities of being able to find and exploit inefficiencies in the market. This is due to the fact that dealers tend to buy at lower prices, and are able to sell at relatively higher prices, reducing the investor's rate of return even more. Current art funds total less than $100 million in capital, representing only a marginal fraction of the current trade in fine art and unlikely at this stage to have any major impact on controlling prices in the art market.

However, the large investors in the art market are influential in price movements. As we have seen, asymmetric information between investors and managers is greater in the art market than in the market for most other financial assets. In the art market, information is imperfect, with participants not necessarily as well informed about the quality, resale value, price, and availability of substitutes. Unlike other financial markets, private art dealers, art funds, and other "influential" investors are able to "make the market." Art funds, with their greater weight, can influence the demand for art by promoting particular artworks and artists. In this regard, the art market differs from traditional investment strategies: As pricing anomalies disappear rapidly in other financial markets, it appears that the art market is able to tolerate their existence for greater periods of time.

Certainly, these inefficiencies present opportunities for exploitation and profit, but conversely represent a danger for the uninformed investor. It is the extent to which these inefficiencies and anomalies exist in the art market that determines the positive abnormal returns that can be made by, but can also lead to loses by, the novice investor. Naturally, this position would be sustainable only in the short term. If more funds enter the marketplace, there will be less room for abnormal profits to be made, although the required skills and knowledge to be an art fund manager mean the entry level is high, with many promising funds having fallen at the first gate while trying to raise enough capital to launch. Until then, the inefficient nature of the market means that if artworks are chosen wisely, attractive returns may be made from alternative investment vehicles specializing in art and art mutual funds in the foreseeable future.

Developments in structured products around art have enabled art investment to become more mainstream and accessible to investors worldwide. Many funds have a high entry level to typically closed funds; however, there is a move toward making the funds more accessible to all investors with shares as low as €2500 for a share in Germany's ARTESTATE, an art fund specializing in German and U.S. contemporary art. Arguably, this would bring the notion of art investment to all sectors of society and, consequently, awaken a greater interest in the market and for up-and-coming artists. The tax breaks in the market amplify the attractiveness of art investment as an alternative investment.

It is not just art funds and banks who are offering structured products around artworks. The Artist Pension Fund provides a novel way of providing retirement provision for artists through a scheme of collective investment into a few chosen artworks over time. It is likely that this type of fund will grow in future, providing a secure retirement provision to an industry with otherwise highly disparate income streams.

Art finance is a new area of international finance which is flourishing primarily to a booming art market and the prevalence of art price data. Art banking is a steadily growing area with many banks offering art banking services. Art is subsequently being considered an alternative asset class, with investment in art purely for financial gain. Although art is an asset class in its financial infancy, from an investment perspective, the market is developing at a rapid pace, and exciting opportunities exist for informed investors to make attractive returns. Despite empirical difficulties associated with pricing artworks, and estimating the true underlying amount of risk, particularly liquidity risk, for an estimated level of historical risk, investors and investment institutions are carefully looking at art as a prospective investment. A number of funds have securitized the purchase of art so that private individuals can own shares in a fund dedicated to fine art investment.

The broader appeal of art as an investment strategy lies in the low correlation with other asset classes. Mean-variance portfolio optimization also shows this using moderate returns for art, even after accounting for the high transaction costs prevalent in the art market.

With the number of art funds on offer steadily increasing it is possible that in the future, a market for a mutual fund of international art funds will develop for investors who seek a truly diversified investment into art, with potentially greater liquidity in the market through greater trading. It is unlikely that art investment will ever become mainstream. Also questionable is whether the art market could cope with such a large investment strategy into the art market, as would be common by institutional investors in other asset classes. What is likely is that a niche alternative investment market is created, with a limited number of funds that have a highly specialized knowledge and level of expertise. The profitable art funds are likely to be hard to replicate, and market efficiencies are likely to stay abound. Indeed, successful art investment is likely to be an art in itself.

Anderson, R. C. (1974). Paintings as an investment. Economic Inquiry 12,1: 13-26.

Ashenfelter, O. (1989). How auctions work for wine and art. Journal of Economic Perspectives 3, 3: 23-36.

Ashenfelter, O., and Graddy, K. (2003). Auctions and the price of art. Journal of Economic Literature 41, 3: 763-788.

Baumol, W. J. (1986). Unnatural value: Or art investment as floating crap game. American Economic Review 76, 2: 10-14.

Campbell, R. (2008). Art as a financial investment. Journal of Alternative Investments 10 (Spring): 64-81.

Chanel, O., Gerard-Varet, L. A., and Ginsburgh, V. (1996). The relevance of hedonic price indices. Journal of Cultural Economics 20,1: 1-24.

Frey, B. R., and Eichenberger, R. (1995). On the return of art investment return analyses. Journal of Cultural Economics 19: 207-220.

Genesove, D., and Mayer, C. (2001). Loss aversion and seller behavior: Evidence from the housing market. Quarterly Journal of Economics 116, 4: 1233-1260.

Ginsburgh, V., Mei, J., and Moses, M. (2007). On the computation of price indices. In V. Ginsburgh and D. Throsby (eds.), Handbook of Economics Art and Culture (pp. 948-979), Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Goodwin, J. D. (2007). A Guide to International Art Markets—Collecting and Investing. London: Kogan Page.

Grampp, W. (1989). Pricing the Priceless—Art, Artists and Economics. New York: Basic Books.

Kochugovindan, S. (2005). Barclays Capital Equity Gilt Study. London: Barclays Bank.

Mei, J., and Moses, M. (2002). Art as an investment and the underperformance of masterpieces. American Economic Review 92,1: 1656-1668.

Mei, J., and Moses, M. (2005). Vested interest and biased price estimates: Evidence from an auction market. Journal of Finance 60, 5: 2409-2435.

Odean, T. (1998). Are investors reluctant to realize their losses? Journal of Finance 53, 5: 1775-1798.

Stein, J. P. (1977). The monetary appreciation of paintings. Journal of Political Economy 85,5: 1021-1035.