We have already touched on the recurring theme of data management at various points in the book. This chapter addresses the subject in detail and introduces a number of different image management systems. It is impossible to stress the importance of a structured image data management system enough. This includes not only a good image browser and a well-structured database, but also a solid and well-thought-out file naming system and an appropriate folder structure.

An integral part of every data management system is a working storage and backup system that you stick to, whether you think you need to or not. Our experience has shown that a reliable backup system should function completely separately from its related data management system. A busy digital photographer will need to save and back up much more than just photos and database files. Although it is late in the book, we hope that we are not dealing with this topic too late for you!

Digital image archives grow much faster than analog archives ever did. Not only do most digital photographers shoot more images due to the low costs involved, but they also tend to save multiple versions of individual images in various formats (RAW, JPEG, TIFF etc.) and for various purposes (optimized for printing or scaled down for web presentation, for example). Managing and finding individual images in large collections is a task that quickly overstretches conventional folder systems, and most photographers find that they sooner or later need to store some images separately from their other digital information.

The naming and folder conventions we outlined in From the Camera to the Computer are a great starting point, but they don’t cover every aspect of the task at hand. Nowadays, specialized Media Asset Management[184] software helps you to do this complex job. This type of software is divided into two major classes:

Image Browser

This type of software allows you to look through images stored in conventional folders and to view enlarged previews. This is quick and easy and can be used just as well for images stored on CDs, DVDs, or other external media using conventional folder structures.

This type of browser is very common, and there are many functional models available as freeware or shareware. Not all browsers support RAW image formats or all types of metadata. Photoshop (CS2 and higher) is delivered with the highly functional Bridge browser built in.

This type of software is great for performing a quick inspection of your material, but it is not suitable for more complex image management purposes. Simple browsers cannot usually handle offline (i.e., not currently loaded) image files. For this type of work you need:

Image Database

Database software recognizes and saves image metadata, allowing you to tag your photos with keywords, classification data, copyright information, comments, and many other types of descriptive information. This data is stored not only in the image file itself, but also in the image database, allowing you to search quickly for specific images or image characteristics within your catalog. The larger your image collection, the less practical it becomes to open every file during a search. Other data management tools, such as virtual folders, smart stacks, or multiple image versions can only be properly managed using a proper image database.

We use database software for our professional-level image data management. Here too, there are freeware, shareware, and commercial programs available for single computers, networks, or complex client-server systems.

The following sections outline the functionality that a good data management system should offer.

The major functions of an image database should include:

Importing and saving image files from multiple sources (camera, memory card, hard disk etc.) and the generation of accompanying thumbnail images. Ideally, these thumbnails should be available even when the original image files are offline.

Thumbnail display for browsing and navigating through your collection. Nowadays, most quality programs can display RAW images and are capable of zooming into these preview images.

A rating system that uses points or stars to rate individual images and a flagging system with colored tags and/or delete flags. A separate sub-workflow for identifying images flagged for deletion is also very useful.

Display and editing of major metadata tags, such as title, description, filename, keywords, categories, or EXIF, IPTC and XMP data. It is useful to be able to apply IPTC data presets to selected images, as switching to a separate editing program is complicated and time-consuming. Renaming batches of images by folder or keyword is also a very useful function.

Simple image manipulation functionality, such as rotation (in 90-degree steps), cropping, moving, or deleting.[185]

File search using tags such as date, keyword, category, image type, resolution, or other image characteristics.

Import and export functionality (including all metadata) for complete or partial image collections.

Useful additional functionality includes:

Index print output (i.e., multiple thumbnails and image titles on one page).

Generation of various presentation formats, such as:

Slideshows or photo and video CDs/DVDs

Albums for printing or online presentation

Contact prints of folders or individual selections

Metadata export for editing using external tools. This can be very useful if you are exporting your images to a different database.

Saving images to external media (CD or DVD) while preserving metadata and index data on the original media. Metadata should be archived, too.

We don’t know of any single program that provides all of the functionality listed above in perfection, but we do try to keep the number of individual programs we use to a minimum. We have provided a roundup of some of the programs currently available in Table 13-1.

Note: No image management program can import data from another program without producing some form of data loss, so be careful to choose the right program for your needs from the outset. Switching databases later always involves reproducing some data by hand – usually a complex and tedious task.

Many cameras and scanners are bundled with image management software, but the programs provided are not usually up to managing large amounts of complex image data. It is usually more economical to buy a commercial all-in-one workflow tool or image management package than to use free but inadequate software.

It is exceedingly difficult to locate images in a large portfolio without the use of metadata. It is impractical to search through large numbers of images visually, but metadata makes it possible to search for individual images quickly and efficiently. Metadata complements the actual image data and is divided into four basic types:

File attributes (such as size and creation date)

Technical shooting data (camera model, aperture, and shutter speed)

Author and copyright data

Classification, keywords, rating, processing status, etc.

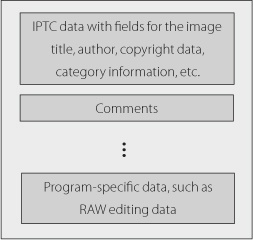

While most metadata is stored directly as part of the image data or with the image data in an additional sidecar file, other metadata (such as slideshow, stack, or other grouping tags) need to be stored on a higher hierarchical level in the image database itself.

File attributes and technical exposure (EXIF) data are usually captured automatically and embedded directly in the image data. Other metadata must be supplied individually by the user or assigned from a separate selection. Good image management systems allow you to copy and paste individual or multiple metadata selections.

Note

![]() Lightroom is one of the best programs available for handling image metadata. It is especially good for downloading or adding IPTC data (in Library mode). Lightroom supports the use of IPTC presets as well as copy and paste for metadata, keywords, and other tags.

Lightroom is one of the best programs available for handling image metadata. It is especially good for downloading or adding IPTC data (in Library mode). Lightroom supports the use of IPTC presets as well as copy and paste for metadata, keywords, and other tags.

Most EXIF data is embedded directly in the image, while other metadata (often with RAW files) is stored in a separate, external file, such as the .xmp files used by Bridge. Most high-end image management programs store metadata in the image database itself with the option to store it in an additional sidecar file. This system can cause data inconsistencies if you edit an image in another program that only changes the sidecar data, but not the data stored in the image database. We would like to see more automatic solutions for these types of problems.

We addressed various types of metadata in Metadata. Remember: some EXIF data is also used by image processing programs. HDR generation software, for example, uses EXIF data to calculate exposure for the individual images in a sequence; and RAW editors use EXIF data to determine which format is being handled, the appropriate camera profile, and the ISO value used in order to help during noise reduction processes. PTLens, DxO, and other RAW editors use EXIF lens, aperture, and focal length data to automate the correction of lens errors.

Generally, there is no reason for the user to edit EXIF data, and most browsers don’t offer EXIF editing functionality. For occasional use (e.g., if the camera date and time were incorrectly set), you can edit EXIF data with specialized programs such as Exifer, ACDSee Pro, or Photo Mechanic (as well as Lightroom and Aperture). Some browser and RAW editors, however, allow you to edit the date and time a picture was shot.

While EXIF and IPTC are well-documented standards,[186] there are a whole range of non-standardized metadata types used by various camera and lens manufacturers that, in turn, lead to different metadata fields being used for different data types. These include the color tags (and other flags) used by Adobe in Bridge and Lightroom, which can be assigned to specific IPTC data fields but which are often assigned to other fields in the internal databases used by other programs.

Confusingly, IPTC and EXIF field names are standardized, but the names assigned to these fields by different camera/software manufacturers are not. This is why some fields have different names in the interfaces of some programs.

Adobe created XMP (Extensible Metadata Platform) in order to exchange information between its own applications in a standardized way. XMP is based on XML (extensible Markup Language) and is an open standard. XMP data can be embedded in object data or stored separately, and it offers predefined and user-definable data fields. For example, Adobe Camera Raw stores the adjustments made to images in XMP format, while Photoshop and Version Cue are capable of storing processing and version histories in the XMP part of an image file. Other RAW editor manufacturers use other formats (or different XMP sections) to save editing steps to parts of XMP files that cannot be read by other programs.

Most types of metadata can be stored in XMP format, and many programs now use this standard, even if there are still some inconsistencies in its implementation. In a digital photographic context, it is an ideal transport medium between programs, and it can even be used to swap RAW correction data between ACR and Lightroom. Many non-Adobe programs are now capable of interpreting and processing XMP metadata; however, they ignore some of the Adobe specific parts, e.g., RAW data correction.

One of the key functions of image management programs is the ability to assign keywords. Navigation by folder, date, or filename is simply not practical when searching through large amounts of image data. Keywords are also often called categories or classifications, although this is not a strict definition – the IPTC standard, for example, also includes a “category” field. There are a number of great books on keywording available, and David Riecks’ website is a good place to start delving deeper into the subject. The following is our own summary of the topic.

Note

![]() Data management without keywords and categories is pretty much useless, as only these attributes make searching possible. It is always worth making the effort to tag your images properly!

Data management without keywords and categories is pretty much useless, as only these attributes make searching possible. It is always worth making the effort to tag your images properly!

David Rieck’s website is: www.controlledvocabulary.com

Your keywords should provide answers to six questions. The list itself comes from David Riecks’ website:[187]

Who | can be seen in the image? |

What | do you see in the picture? |

Where | is the subject located? |

When | was the photo shot (provided this is not covered by EXIF data)? |

Why | was the photograph taken and why is the content important? |

How many | people or objects are included in the picture? |

The IPTC specification has its own rules regarding keywords:

Each keyword (or key phrase) must not be more than 64 characters long. You can, however, use several keywords in each keyword field.

The total keyword entry should not be more than 2,000 characters long. The current IPTC standard allows for more, but 2,000 characters ensure backward compatibility with previous versions of the standard.

Keywords are separated by commas or semicolons followed by a space.

Ask yourself the same questions we listed above when entering data into the IPTC caption field.

A restricted vocabulary (preferably a predefined list of keywords) is recommended. This guarantees uniform spelling and reduces the variety of words used for similar circumstances.[188] This applies only to general concepts, but not to names and special locations (e.g., Bryce Canyon or Hearst Castle). When assigning keywords to an image, think about how you will search for them later. Use plural categories – e.g., Mountains instead of Mountain or Cattle instead of Cow.

Some programs allow you to create a keyword hierarchy. For example, if you enter Manhattan, New York and USA are also automatically generated and entered. There are lists of predefined keyword hierarchies available on the Internet (for free and commercially) for hierarchy-compatible programs (such as Aperture and Lightroom).

Don’t worry too much about your keyword conventions – less is often more. Even if it contradicts what we said before, it helps if certain concepts are represented by several spellings, especially when place names with no fixed spelling are concerned.

It is sometimes useful to use basic IPTC caption data when presenting your images in a slideshow or on the Web. If your software allows, you can use metadata to group images into virtual folders.

Digital asset management systems such as Aperture, Lightroom, Bibble 5, Expression Media, or Extensis Portfolio store metadata in their database, allowing for quick search and retrieval. If you want to make metadata accessible to external applications, too, you need to embed metadata in your image files. Lightroom allows you to do this either automatically after every change to image data, on demand, or (optionally) when exporting your images.[189]

It is usually best to assign keywords (that apply to all images in a shoot) directly during download. If your software doesn’t allow you to do this, apply the major keywords directly after downloading by using multiple selections in your image browser. You can then select groups of images within the shoot and assign keywords to them. If your browser or image management software doesn’t support this type of function, you have chosen the wrong tool! This way, you can gradually fine-tune your keyword lists, right up to the point where you assign single keywords to individual images. One of the best keywording tools currently available is Adobe Lightroom.

We recommend that you always enter the most important IPTC copyright data (Figure 13-2) during or directly after download using a predefined IPTC preset. This functionality is included in Bridge, Lightroom, Aperture, Photo Mechanic [60], and Downloader Pro [40], but applying presets to multiple selections later is also an adequate way to label your images.

Some IPTC data fields (e.g., scene, category, genres, and country) have predefined codes. Countries, for example, are identified using two- or three-character ISO 3266 abbreviations.[190] However, we don’t know of any image management program that forces you to use predefined ISO values, and you can decide for yourself whether you want to stick to the scheme ([110]). If you use your own codes, we recommend that you always use the same terms or simply leave the data fields empty.

There is also an explanation of the various IPTC fields and conventions under IPTC Core Schema for XMP. Customer Panel User Guide [110]. David Riecks’ website [125] is also a great source of information on the subject of metadata.

We recommend that you make a title entry and a short description for the images you have tagged with one or more stars, as this information is often useful for display in slideshows or Web galleries. Bridge and Lightroom call these fields “Title” and “Caption”. Other programs may have other names for these fields.

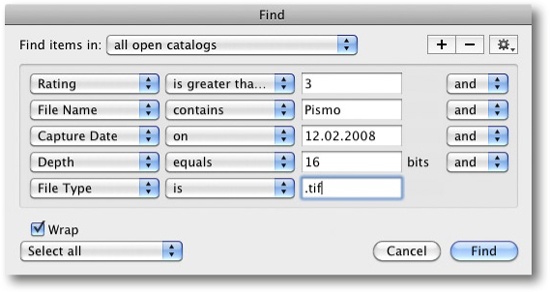

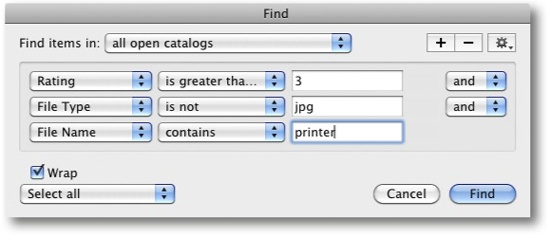

Ideally, you will be able to perform image searches based on EXIF or IPTC data and keywords, or any combination of them – for example, all architectural images shot in 2009 using my Nikon D3.

Most image management programs allow you to display EXIF data but don’t necessarily allow you to use that data as search criteria. Simpler terms (i.e., categories or specific time periods) are usually sufficient for performing most searches. Search results are usually displayed either as a list of filenames or as folder full of thumbnail previews. Many browsers also allow you to use exclusion criteria in order to leave certain images out of a search.

Figure 13-3. A good search tool will allow you to combine criteria, as shown here in Microsoft Expression Media 2.

Assigning metadata to new images is often tedious, but always necessary! You will be glad you did as soon as your collection gets beyond a certain size and searching through your folders visually takes too long.

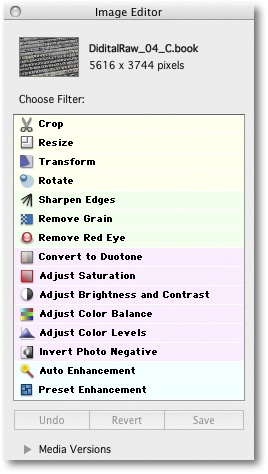

Most image browsers and image management programs also include simple image optimization functionality, such as RAW conversion, image rotation, cropping, and color and saturation correction. We usually use only the rotation function (if at all), as the other functions are not generally up to the standards offered by Photoshop or good RAW editors.

We also use specialized software for performing our RAW conversions because the speed and quality are generally greater than that provided by multi-function browsers and image managers. We do, however, use image browsers and managers for generating preview images for our database. You can usually drag images from your browser to a RAW converter at the actual conversion stage. Most browsers also allow you to select which program you use to open your images. (All-in-one workflow tools such as Apple Aperture or Adobe Lightroom are an exception and include high-quality optimization tools.)

It is often an advantage to allow your image management software to take control over your entire image processing workflow. In practice, this means using your management software to open all images and image processing programs, so that all changes are sure to be registered in the image database. This approach ensures that the database and all preview images are current, and that all new image versions are included in the database. Used this way, image management software functions in a similar way to document management systems.[191] This can take some getting used to if you are not familiar with this type of system, but it is essential if you want to enjoy all the advantages of your image management software to the full.

Some image management programs allow you to store imported images in secure memory that cannot be accessed from outside the program. We use our own (open) folder structure for storing our images and point our import process to the appropriate folders. This makes backup easier and helps us to preserve an overview of our homemade folder structure. If you take this sort of approach, remember not to rename or move files outside of your image management program – otherwise you will quickly produce inconsistencies between your image files and your database.

High-quality image management programs allow you to inform them when you move single images or image collections (e.g., when you switch computers or start using a new external hard disk).

We described a useful file storage and naming system for imported data in Downloading and Organizing Your Images. But where is the best place to store converted, processed, or print-ready versions of our originals? There are two basic ways to approach this question:

Store your newer versions in the same folder as your originals (or in a subfolder within the same folder). This keeps the basic folder structure simple, and files that belong together can be easily moved or renamed.

The disadvantage of this approach lies in the fact that it mixes changed files[192] with your originals, although the originals themselves have not changed since import.

This approach also means that you will have to browse through an unnecessarily large number of images, including duplicates or ones that you have flagged for deletion later on. You can reduce this effect by using custom stacks and views.

Backups for this type of folder structure should always include the entire folder tree or branch in order to ensure copying all changed image data.

Save originals and newer versions in separate folders or even in separate partitions or on separate disks. Once you have backed up your originals once, you will only have to back up the files that have changed recently.

Your library of newer image versions no longer needs to be organized strictly chronologically or according to individual shoots, but can instead be organized according to customer numbers, individual themes, or other custom criteria. Such a folder structure contains only preselected, optimized, or other finished images. You no longer have to wade through intermediate HDR images or the individual source images that make up a panorama.

The path back to the original image follows the filename of each image, so a strict naming convention is essential.

It is up to you to decide which approach you take, but a good image management program will help you organize your library, however you decide to proceed.

Nowadays, most memory media are reliable but not always fault-free. Damaged image files can remain unnoticed, and once you have mistakenly saved and backed up a corrupt (but readable) image file, you will only have an unusable image left over. It is impossible to visually check your entire library for errors on a regular basis, so you will need to use other techniques to ensure ongoing data integrity.

One way to check your files is to generate and save checksums for your altered files. This type of test method is not yet available as an integral part of normal computer file systems, but we hope that this situation will change in the near future. There are, however, programs available that automatically recalculate the file checksums, compare them with the saved versions, and raise an alarm if errors are detected. Such solutions have been available for UNIX and Linux systems for a while now, but they usually have command-line interfaces that make them less user-friendly.

Adobe’s DNG Converter can automatically check entire RAW libraries for errors using just the change log,[193] and it issues a warning if files are found to contain errors. DNG converter does not, however, support very many file formats, and Marc Rochkind’s ImageVerifier [103] is generally a better solution. This program costs about $40 and fully automates the checksum process described above for JPEG, RAW, DNG, PSD, and TIFF files. (The program is available for Windows and Mac systems.)

When you detect a problem (a mismatch), all you need to do is replace the faulty files with a backup copy and run a check on the copy to make sure that it is error-free.

As well as checking your image files, it is a good idea to use the tools built into the operating system to regularly check the consistency and integrity of your computer’s file system. We run this type of check about once a month, or before every major backup run. If a disk shows read or write errors, save your data and replace the disk. Using SMART software to continually check the health of your disks is a good way to avoid disk failures. Modern hard disks are capable of self-checking and saving error warnings in internal memory. There are a number of manufacturers’ own and third-party programs available for analyzing error warnings.

The difference between an image browser and a true image database lies in the degree of database functionality the software offers. Most of the browsers included with RAW editing software (such as Adobe Bridge) are still basically browsers, even if some of them use enhanced cache files to simulate database functionality. ACDSee Pro also uses cache technology to simulate database functionality, but it’s just an enhanced browser.

Different programs support different ranges of file formats. All-in-one workflow tools, such as Apple Aperture, Adobe Lightroom, and Bibble 5, are strongly oriented to the digital photography market and (unfortunately) don’t support PDF, video, or audio formats. They usually also don’t support CMYK image files (well, Lightroom 3 does). Purpose-built Digital Asset Management (DAM) programs such Phase One Expression Media, Extensis Portfolio, or Canto Cumulus are more versatile and support a range of up to 150 different file formats, plus a range of proprietary RAW formats.

Once your image library reaches a certain size, you will need to use a database to keep track of your data. Database software is divided into single-user or server-based programs. Expression Media, Lightroom, Aperture, and Bibble 5 are examples of single-user programs, and they are usually sufficient for most photographers’ needs.

If you need to make your image data available to multiple users or on a network, you need to use server-based software. Here, you can start a client program on a computer that accesses the actual image database remotely. Extensis Portfolio and Canto Cumulus can be used this way, and the price of a license depends on the number of users. This is the type of solution most often used by image agencies where most employees are given read privileges. Only the database administrator is allowed to write and change image data.

Expression Media 2 is one of the better programs for our purposes, and we will use it as an example in the following sections. However, for a long time, we did not see any further development of the application by Microsoft. Finally, in 2009, Microsoft sold the tool to Phase One, the manufacturer of Capture one. We hope Phase One will do better and integrate Capture One and Expression Media into a single application. We have also had positive experiences using Extensis Portfolio.

Table 13-1. Image Management Programs

Platform | Approx. Price | Comments | |

|---|---|---|---|

Enhanced Browsers | |||

ACD Systems ACDSee Pro www.acdsystems.com | $40 | Widespread in Windows environments. A simple DAM system at a reasonable price. | |

Camera Bits Photo Mechanic www.camerabits.com | $150 | Strong IPTC support, comparison of several images possible, automatic backup on second disk, multiprocessor support. Supports XMP. Quite fast. | |

Breeze Systems Breeze Browser Pro www.breezesys.com | $90 | Supports tethered shooting for several camera models if the camera is connected to the computer via a USB port. | |

Entry-level Image Management Programs | |||

Google Picasa http://picasa.google.com | Free | Free, but no RAW support. Only suitable for small libraries. | |

Apple iPhoto www.apple.com | $80 | Limited functionality, but under constant development. It is part of Apple’s iLife bundle. | |

H&M Software StudioLine Classic www.studioline.net | $60 | Integrated non-destructive processing functionality. CD/DVD archiving possible. | |

Adobe Photoshop Elements www.adobe.com | $75 | Simple all-in-one workflow tool. The Windows version provides its own image database, whereas the Mac version uses Adobe Bridge. | |

ACDSee Systems Photo Manager www.acdsystems.com | $110 | Database-based. Includes XMP support and some image processing functionality. | |

Semi-professional and Professional-level Packages | |||

Extensis Portfolio www.extensis.com | $200 | Single-user version of the same manufacturer’s professional client-server database software. | |

Expression Media 2 www.phaseone.com | $200 | Supports a large number of formats including RAW. Good XMP and IPTC support. Very popular. | |

Canto Cumulus (Single User) www.canto.com | $300 | Single-user version of the professional media database. Good search features. Supports scripting. | |

photools.com IMatch www.photools.com | $65 | Good XMP and IPTC support. Can be used to manage offline image data. | |

TTL Software ImageStore ttlsoftware.com | $50 | Also available in the enhanced StudioFlow version, aimed at studio use. | |

All-in-one Workflow Tools | |||

Apple Aperture www.apple.com | $200 | Covers the entire photo workflow. Very resource-intensive. Elegant interface. Many plug-ins available. | |

Adobe Lightroom www.adobe.com | $300 | Covers the entire photo workflow. RAW converter based on ACR engine. Good support for printing, slideshows, and Web galleries. | |

Bibble Labs Bibble 5 www.bibblelabs.com | $200 | Covers the entire photo workflow. Quite fast. Many plug-ins available. | |

Expression Media 2 used to be known as iView Media Pro until it was bought by Microsoft (subsequently resold to Phase One in 2009). The program is available for Windows and Mac systems and has an attractive, easy-to-use interface. It supports a wide range of photo, RAW, and multimedia formats, including TIFF, PSD, JPEG, JPEG 2000, a selection of audio and video formats, PDF, and much more. Expression Media also supports offline media and can display previews for images that are not currently loaded. The additional free Media Reader allows you to access Expression Media catalogs over a network and can also be reproduced and given away with collections burned to DVD. The program does not provide true client-server functionality, and only allows one user at a time to access and write data.

(

,

) Expression Media: www.phaseone.com

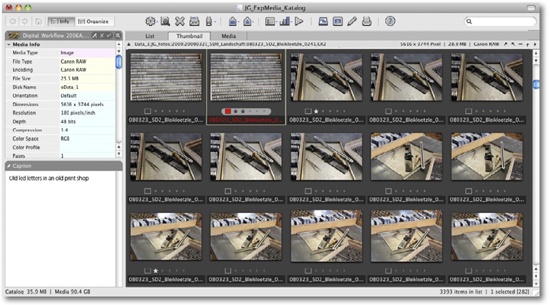

The program’s preview interface is highly configurable (Figure 13-4). Here too, you can rate your images using stars and color codes. You can view and sort the display according to rating, keyword, creation or alteration date, file size, category, and a range of other criteria.

The program’s information panel displays general image data as well as metadata, including the filename, file size, media type, and EXIF and IPTC data (although these are not referred to by name here). The program allows you to edit IPTC data and (unusually) the image shooting date, in case the camera’s date is incorrectly set.

You can save an image’s IPTC data along with various other variable metadata attributes as a preset that can then be applied to other images. This is a great help if you need to import large numbers of images. The program’s built-in downloader also allows you to batch rename images.

Expression Media 2 includes a number of built-in image processing tools (Figure 13-5). Of these, we only use the Rotate tool. We also use the version control feature, which saves all previous versions of an image for later recall.

You can configure the program to start specific applications for specific media types by double-clicking on a preview icon. Apple QuickTime (also available for Windows) is the default application for many media types.

You can open multiple archives in separate windows and drag files from one to another – functionality that is not available in any of the all-in-one tools we know. Import speed is not tremendous, but acceptable. The quality of the program’s RAW conversion is fine for generating preview images, but not as good as that provided by purpose-built RAW converters. You can import images from existing iPhoto and Photoshop albums and there is also a hot folder feature for instant download of images shot using a camera that is directly attached to your computer.

Expression Media generates virtual folders (as described in Views) using Catalog Sets. Once you create a set, you can drag images or search results to the set entry. A single image can be part of multiple virtual folders, and a catalog set can also contain a hierarchy of multiple subsets.

Expression Media 2 offers a range of complex search criteria (Figure 13-6) that extend to cover multiple Catalogs. Searches can be saved and reused to create virtual folders.

The program supports full-screen previews for online images, and you can compare up to four images at once on a virtual light table.

Expression Media supports simple printing (without Photoshop-style color space support) for single images, contact prints, and content lists. You can also create Web galleries and videos for export and display on a TV. The range of functions available for customizing Web galleries or slideshows is not as comprehensive as those available in Aperture or Lightroom.

You can use the program to save data to CD, DVD, or hard disk and you can even export image metadata in XML format.

Traditional image management programs focus on the variety of different digital media types (or assets) they can handle, while their actual image processing functionality plays a secondary role. This is the factor that makes such programs less suitable for integration in the digital photo workflow. We recommend that you don’t use your browser’s built-in processing tools if you don’t have to.

The advantage of the image management programs described here is their ability to handle diverse media formats, including HD video and CMYK images – formats that are becoming increasingly popular among photographers. We assume that the best-known all-in-one workflow tools will follow suit and support the same formats in the near future.[194]

If you shoot primarily in JPEG or TIFF format, the differences between a DAM- or an all-in-one-based workflow are not that great. Most image management programs have fast preview modes for popular image formats and they usually use other, external programs to display formats that they don’t support directly. Just like RAW converters and all-in-one programs, they generate JPEG previews for RAW images. Image management programs are generally slower and not as powerful as their specialized cousins when it comes to RAW conversion and display.

If, as we do, you use Photoshop as your main image processing tool, Lightroom offers certain advantages over Apple or Bibble 5 – for example, simple data transfer for HDR or panorama creation, or for generating Smart Objects.

We consider Photoshop to be indispensable, independent of whether you use an all-in-one workflow tool or a traditional image database to manage your images. Using Photoshop with Bridge is fine for handling smaller image libraries; you will only need a true image database tool once your image collection reaches a certain size.

Aperture, Lightroom, or Bibble 5 are a better choice than Expression Media, Portfolio, or Cumulus if you want to produce Web galleries, slideshows, or make complex prints.

Adobe Photoshop Elements, Apple iPhoto, and ACDSee represent good value for digital photo beginners, but are not really suitable for use as part of an advanced workflow that contains large numbers of images.

Image management programs can be useful for handling large amounts of non-photographic digital assets, but an all-in-one tool combined with Adobe Bridge and a carefully planned folder structure usually suffices.

By default, Digital Photo Pro (DPP), Photoshop Elements, and Lightroom install a program that automatically downloads data from your card reader to their own preset data location. This is annoying, and we deactivate this function wherever it is present, even if it involves editing the Windows registry.

Integrating image management with other components of the digital photo workflow is not always easy, and image data can easily get lost during transfer between programs. It is difficult to please everyone and to cover all the bases in the complex world of digital image processing, but we are certain that future versions of quality image management programs will continue to improve in this respect.

[184] Or image archive, image database, media database etc.

[185] Some databases also include simple, automatic tonal value, color, and contrast correction functionality. We do not, however, use these in our workflow.

[186] There are also various versions of these standards in circulation, and not every software manufacturer uses the latest version. This can lead to inconsistencies when exchanging data between programs.

[188] Using a thesaurus to decide which words are permissible and how they are spelled makes it easier to standardize your own keywords.

[189] Metadata is embedded directly in TIFF, JPEG, and DNG files. RAW files use an XMP (Extensible Metadata Platform) sidecar file to store metadata.

[190] The country code for the USA is “US”.

[191] Images that require extensive processing can be individually exported and re-imported after processing.

[192] I.e., images that require constant work or ones that produce new variants (for printing or presentation, for example).

[193] DNG Converter is capable of automatically checking entire folder trees.

[194] Starting with version 3, Lightroom supports L*a*b* and CMYK files, though in a somewhat limited way.